Assurance Coursebook: Malawi Accounting Technician Diploma

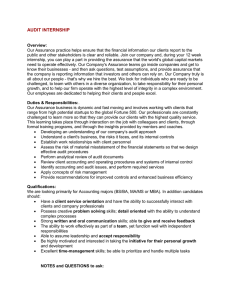

advertisement