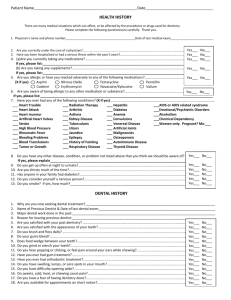

`Ìi`ÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊ`iÊÛiÀÃÊvÊ vÝÊ*ÀÊ* Ê `ÌÀÊ /ÊÀiÛiÊÌ ÃÊÌVi]ÊÛÃÌ\Ê ÜÜÜ°Vi°VÉÕV° Ì `Ìi`ÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊ`iÊÛiÀÃÊvÊ vÝÊ*ÀÊ* Ê `ÌÀÊ /ÊÀiÛiÊÌ ÃÊÌVi]ÊÛÃÌ\Ê ÜÜÜ°Vi°VÉÕV° Ì This page intentionally left blank `Ìi`ÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊ`iÊÛiÀÃÊvÊ vÝÊ*ÀÊ* Ê `ÌÀÊ /ÊÀiÛiÊÌ ÃÊÌVi]ÊÛÃÌ\Ê ÜÜÜ°Vi°VÉÕV° Ì Charles A. Babbush, DDS, MScD Director, ClearChoice Dental Implant Center; Clinical Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Director, Dental Implant Research Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine Cleveland, Ohio Jack A. Hahn, DDS The Cosmetic and Implant Dental Center of Cincinnati Cincinnati, Ohio Jack T. Krauser, DMD Private Practice in Periodontics Boca Raton, Florida, and North Palm Beach, Florida Faculty, Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery University of Miami School of Medicine Miami, Florida Joel L. Rosenlicht, DMD Private Practice Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Manchester, Connecticut; Assistant Clinical Professor Department of Implant Dentistry College of Dentistry New York University New York, New York With 1638 illustrations 3251 Riverport Lane Maryland Heights, Missouri 63043 Dental Implants the Art and Science Copyright © 2011, 2001 by Saunders, an affiliate of Elsevier Inc. ISBN: 978-1-4160-5341-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights Department: phone: (+1) 215 239 3804 (US) or (+44) 1865 843830 (UK); fax: (+44) 1865 853333; e-mail: healthpermissions@ elsevier.com. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier website at http://www.elsevier.com/ permissions. Notice Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. Readers are advised to check the most current information provided (i) on procedures featured or (ii) by the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications. It is the responsibility of the practitioner, relying on their own experience and knowledge of the patient, to make diagnoses, to determine dosages and the best treatment for each individual patient, and to take all appropriate safety precautions. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the Authors assumes any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of the material contained in this book. The Publisher Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dental implants : the art and science / [edited by] Charles A. Babbush … [et al.].—Ed. 2. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4160-5341-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Dental implants. I. Babbush, Charles A. [DNLM: 1. Dental Implants. 2. Dental Implantation—methods. WU 640 D4142 2011] RK667.I45D485 2011 617.6′9—dc22 2009045447 Vice President and Publisher: Linda Duncan Executive Editor: John Dolan Senior Developmental Editor: Courtney Sprehe Publishing Services Manager: Catherine Jackson Senior Project Manager: Rachel E. McMullen Design Direction: Amy Buxton Working together to grow libraries in developing countries www.elsevier.com | www.bookaid.org | www.sabre.org Printed in China Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 A B O U T T H E C O V E R The cover of this book illustrates a variety of state-of-the-art concepts that are representative of the content found in the text. The background image is a cone beam CT scan of a maxillary and mandibular All-on-4 postoperative patient. The six photographs in the right-hand vertical column show (from top to bottom): 1. A Nobel Active implant before insertion 2. A Lucite patient education model of a classical All-On-4 implant reconstruction 3. An example of a Procera plan from 3-D software without the prosthesis or bone icon being active 4 and 5. The 5-year follow-up panoramic radiograph and clinical photograph that demonstrates the results of tooth extraction, immediate implant placement, immediate provisional restoration, and permanent restorations 6. A virtually created surgical guide, in which the parallel placements of the implants can be visualized with the facial position of fixation screws; the template of the maxilla completes the plan v In this, my fourth textbook, I feel it is only appropriate to dedicate it in several different categories. First, to my colleagues who have worked with me, and my patients, over these 42 years of implant reconstruction, I am deeply honored. I am even more honored by the dedication and loyalty of the thousands of patients who have trusted my skills, knowledge, and experience. In addition, I feel it only appropriate to list some of my mentors and colleagues who also led the way in this field and shared so generously: Paul Mentag, Leonard Lindow, Isiah Lew, Aaron Gershkoff, Norman Cranin, Axel Kirsch, P.I. Brånemark, and Jack Wimmer. My family has supported, encouraged, complimented and even advised me, which ultimately has allowed me to continually contribute to society and share this work, which also allows me to continue to change lives on a daily basis. Of these family members, my wife, Sandy has, for 50 years, been my chief critic, advisor, constant companion, as well as my best friend. Our children, Jill, Jeff, Amy, David, and Debbie are a great source of fun, love, understanding, and, now that they have matured, advice. Lastly, I thank my seven grandchildren, wonders of the world, Alex, Max, Lexie, Joey, Sam, Sydney, and Grace, for the affection, enjoyment, and unlimited love. Charles A. Babbush I would like to dedicate my participation in this book to my wife of 47 years, Barbara, and my children, Julie, Jeff, and Greg, who were patient and supportive during my 39 years in implant dentistry. I also want to thank the pioneers and teachers who were responsible for influencing my professional life. Jack A. Hahn I am extremely pleased to have been part of this exciting literary venture. I’d like to dedicate it to several people, and categories, who have had a profound influence on me and my career. My co-authors: “Sir Charles” Babbush was one of my initial educational experiences in implant dentistry, and I can still remember his enthusiasm and passion for our field exemplified at his lecture at the University of Miami in 1985. “Big Jack” Hahn, has been a mentor to me on many levels including the profession as well as a role model of the family man, who I’ve known for many years. Joel Rosenlicht is my contemporary who has shared many of life’s ups and downs with me, and has always been a true buddy. My co-authors are outstanding people and master clinicians. My parents, Al and Sheila Krauser, have given me so many attributes, love, caring, insight, and concepts of living a good life, that I can write a book about them. They were both schoolteachers, and as educators, I have always learned and known of the value of education … even worth more than material things. They are active with friends and family in many cultural, travel, and athletic activities and have set a wonderful model for my career and life. A few colleagues in our field have been tremendously influential on many levels: my lecturing buddies Scott Ganz, Marius Steigmann, Team Atlanta, Mike Pikos, Ziv Mazor, and Bobby Horowitz. My foundational colleagues are Mort Amsterdam, Frank Matarazzo, Alan Levine, Clive Boner, Neil Boner,Vincent Celenza, Andrew Schwartz, Al Mattia, Steve Feit, Michael Radu, Steve Norton, and Bill Eickhoff. Finally, my daughter Taylor, now in high school, may fully appreciate the efforts of these dedicatees on her life as well as mine. This soon to be classic text in implant dentistry will be an inspiration for her. Thank you also to the highly dedicated staff at Elsevier, who put up with my chapter delays! Jack T. Krauser Congratulations to Charles Babbush and the other editors of this wonderful text. These co-authors have been inspirational and motivating for me in my journey with implant dentistry. I’d also like to thank my wife, Doreen, and our children Jordan, Tyler, and Sarrah for their patience and understanding while being away from them while pursing my passion for implant dentistry. Lastly, my parents, Bernice and Paul, whose vision and support encouraged me to be a dentist. Joel L. Rosenlicht C O N T R I B U T O R S This ebook is uploaded by dentalebooks.com Ryaz Ansari, BSc, DDS Rosenlicht and Ansair Oral Facial Surgery Center Manchester, Connecticut Debora Armellini, DDS, MS Prosthodontist ClearChoice Dental Implant Center—Washington DC Washington, DC Charles A. Babbush, DDS, MScD Director, ClearChoice Dental Implant Center; Clinical Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Director, Dental Implant Research Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine Cleveland, Ohio Stephen F. Balshi, II, MBE Chief Operating Officer CM Ceramics, USA Mahwah, New Jersey Thomas J. Balshi, DDS, FACD Chairman of Board Institute for Facial Esthetics Fort Washington, Pennsylvania Barry Kyle Bartee, DDS, MD Assistant Clinical Professor Department of Surgery Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine; Private Practice in Implant Practice Lubbock, Texas Edmond Bedrossian, DDS, FACD, FACOMS Private Practice; Director, Implant Training University of Pacific OMFS Residency Program San Francisco, California James R. Bowers, DDS Clinical Institute Department of Fixed Prosthodontics Kornberg School of Dentistry Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania L. Jackson Brown, DDS, PhD President, L. Jackson Brown Consulting, LLC Leesburg, Virginia; Editor, Journal of Dental Education The American Dental Educational Association Washington, DC Cameron M.L. Clokie, DDS, PhD, FRCD(C), Dipl. ABOMS Professor and Head Department Oral Maxillofacial Surgery University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario, Canada J. Neil Della Croce, MS Temple Dental Student Director School of Dentistry Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Research Associate/Clinical Assistant/Student Director PI Dental Center at the Institute for Facial Esthetics Fort Washington, Pennsylvania Ophir Fromovich, DMD Head, Dental Implant Academy of Excellence Petah-Teqva, Israel Scott D. Ganz, DMD Private Practice in Prosthodontics, Maxillofacial Prosthetics, and Implant Dentistry Fort Lee, New Jersey Adi A. Garfunkel, DMD Professor; Former Head Department of Oral Medicine; Dean Emeritus Hadassah School of Dental Medicine The Hebrew University Jerusalem, Israel vii viii Contributors Arun K. Garg, DMD Professor Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; School of Medicine University of Miami Miami, Florida; Director, Center for Dental Implants of South Florida Aventura, Florida Celso Leite Machado, DDS Chief Clinical Professor of TMJ Arthroscopy Surgery Miami Arthroscopy Research, Inc. Miami, Florida; Director, International Research/Medical Workshop, Coordinator, International Biological Inc. Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan; Director of Cosmetic and Implant Dentistry, SPA-MED Guaruja, São Paulo, Brazil Michelle Soltan Ghostine, MD Resident Physician Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery Loma Linda University Loma Linda, California Paulo Maló, DDS Maló Clinic Lisbon, Portugal Jack A. Hahn, DDS The Cosmetic and Implant Dental Center of Cincinnati Cincinnati, Ohio Sven Jesse, DLT Jesse and Frichtel Dental Labs Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Benny Karmon, DMD Private Practice Petach-Tikva, Israel Jack T. Krauser, DMD Private Practice in Periodontics Boca Raton, Florida, and North Palm Beach, Florida; Faculty, Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery University of Miami School of Medicine Miami, Florida Ronald A. Mingus, JD Shareholder Reminger Co., LPA Cleveland, Ohio Craig M. Misch, DDS, MDS Private Practice Prosthodontics and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Sarasota, Florida; Associate Professor David B. Kriser Dental Center Department of Implantology New York University New York, New York Miguel de Araújo Nobre, RDH Director Department of Research and Development Maló Clinic Lisbon, Portugal Richard A. Kraut, DDS Chairman Department of Dentistry; Director Oral and Maxillofacial Residency Program; Associate Professor Department of Dentistry Albert Einstein College of Medicine Montefiore Medical Center Bronx, New York Marcelo Ferraz de Oliveira, DDS Clínica Groot Oliveira São Paulo, Brazil; Coordinator, Craniofacial Prosthetic Rehabilitation P-I Brånemark Institute Bauru, Brazil Jan LeBeau Moorpark, California Stephen M. Parel, DDS Prosthodontist Private Practice, Implant Surgery Dallas, Texas Isabel Lopes, DDS Clinical Instructor Department of Oral Surgery School of Dental Medicine University of Lisbon Maló Clinic Lisbon, Portugal Loretta De Groot Oliveira, BSC, BMC Clínica Groot Oliveira São Paulo, Brazil Arthur L. Rathburn, MS Founder and Research Director Department of Continuing Education and Research International Biological Inc. Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan ix Contributors Eric Rompen, DDS, PhD Professor and Head Department of Periodontology/Dental Surgery University of Liège Liège, Belgium Joel L. Rosenlicht, DMD Private Practice Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Manchester, Connecticut; Assistant Clinical Professor Department of Implant Dentistry College of Dentistry New York University New York, New York Richard J. Rymond, JD Adjunct Assistant Professor Department of Community Dentistry School of Dental Medicine Case Western Reserve University; Sharesholder, Secretary, Vice President Chair, Dental Liability Reminger and Reminger Co, LPA Cleveland, Ohio Bob Salvin, BS Founder and CEO Salvin Dental Specialites, Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina George K.B. Sándor, MD, DDS, FRCDC, FRCSC, FACS Professor The Hospital for Sick Children Toronto, Ontario, Canada Dennis G. Smiler, DDS, MScD Private Practice Encino, California Muna Soltan, DDS, FAGD Private Practice Riverside, California Samuel M. Strong, DDS, Dipl. ICOI, ABDSM Adjunct Professor Dental School University of Oklahoma Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Private Practice Little Rock, Arkansas Stephanie S. Strong, RDH, BS Private Practice Little Rock, Arkansas Lynn D. Terraccianao-Mortilla, RDH Adjunct Clinical Professor Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology Kornberg School of Dentistry Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Evan D. Tetelman, DDS Assistant Clinical Professor Department of Comprehensive Care School of Dental Medicine Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, Ohio Konstantin D. Valavanis, DDS Private Practice ICOI Diplomate Athens, Greece Eric Van Dooren, DDS Visiting Professor Department of Periodontology and Implantology Université de Liége Liége, Belgium Tomaso Vercellotti, MD, DDS Inventor, Piezoelectric Bone Surgery, Honorary Professor Periodontal Department Eastman Dental Institute London, United Kingdom; Visiting Professor Periodontal Department University of Bologna Bologna, Italy James A. Ward, DMD Former Chief Resident; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Temple University Hospital Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Associate Physician Department of Oral Surgery Saint Mary’s Medical Center Langhorne, Pennsylvania Glenn J. Wolfinger, DMD, FACD Board of Directors Institute for Facial Esthetics Fort Washington, Pennsylvania F O R E W O R D Googling the name “Dr. Charles Babbush” results in 10 pages of references to the oral surgeon from Cleveland, Ohio, and to his contributions to the field of dental implantology. In a society that glorifies the “here and now,” Dr. Babbush has held a prominent place on the dental implant stage for more than 40 years. The impact Dr. Babbush has had in the field of dental implants, as a clinician and a teacher, is undeniable. That he again has taken the time to edit an additional text, co-authoring it with such prominent clinicians and teachers as Drs. Jack Hahn, Jack Krauser, and Joel Rosenlicht is a testament to his devotion and dedication to his profession. The first edition of this text has a prominent place on my shelf. The word “art” embraces many facets and influences, whereas the word “science” incorporates many known facts. Although art may be in the eyes of the beholder, science promulgates accepted knowledge. It is fitting that a dentist with the broad background and scientific experience of Dr. Babbush accepted the challenge of bringing these topics together in one place as a resource for dentistry. Not only has he brought together a virtual “who’s who” in implant dentistry for this edition, he has also contributed significantly himself. The reader will find in this volume a thorough review of implant dentistry. Dr. Babbush has taken a sound approach by starting with a discussion of the demand for dental implants by consumers and the master planning of the potential dental implant patient. He includes a detailed discussion of surgical and prosthetic procedures. The often overlooked subjects of the business of implant dentistry and systems for team success in the implant practice are also discussed. Technological advancements in dentistry envelope us at a furious pace, and these are nowhere more evident than in areas of CT/CBCT use and guided implant placement. This edition and its authors strive to meld this area of rapidly developing science with the art of the esthetic restoration that consumers demand. The subject of immediate implant function and esthetics is presented by leading experts in the field, who share the current science of this treatment so beneficial to patients. In addition to these scholarly contributions, this volume continues to add pertinent information to the scientific knowledge base with a discussion of newer clinical procedures, angled implants, and new implant design, and concludes with a review of maintenance issues, complications, and failures by highly experienced dental implant professionals. Implant dentistry is no longer an art conducted solely by dental specialists. Instead it is shared by general dentists who, along with specialists, dedicate themselves to the “art and science” of this field. Dr. Babbush and his co-authors have created a significant work of interest to all disciplines. The sheer depth of this work, along with the illustrious contributors, should ensure its relevancy to all of our practices for years to come. I first met Dr. Babbush more than 40 years ago when he was my teacher at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. He has served on our faculty over all these years, and we have become professional colleagues as well as friends. As our relationship has grown, so has his capacity as an educator, researcher, and advisor. His ability to relate to students, faculty, and peers is impressive. This is evidenced by his many awards and honors that include numerous visiting professorships such as Nippon Dental University, Nigata, Japan; College of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; University of Miami, School of Medicine Department of Surgery, Miami, Florida; and Sri Sai College of Dental Surgery, Hyderabad, India. His passion for continual improvement of himself and his profes- sion keeps him on the cutting edge of implant dentistry. He is distinguished by his willingness to honestly share his experiences and knowledge, which is a hallmark of a true educator. He does this for the betterment of his peers. Dr. Babbush’s excitement for the field of implant dentistry is evident in his fourth textbook, in addition to As Good as New: A Consumer’s Guide to Dental Implants. He and his new co-authors have gathered together a real “who’s who” of implant dentistry. This broad scope of work is applicable not only to the basics for the pre-doctoral students, but also to the specialist. It should even be of interest to the experienced practitioner. This book, like his others, is noteworthy for its clarity, organization, intellectual approach, and generosity. The book not only x Mark W. Adams, DDS, MS Director of Prosthodontics ClearChoice Dental Implant Center—Denver Denver, Colorado Foreword xi features the most progressive approaches to treatment, but also applies Dr. Babbush’s 42 years of implant experience, along with the massive number of years of expertise of his participants, to look into problems, complications, and accompanying suggested solutions. Dental Implants: The Art and Science, Second Edition presents new refreshing subject matter not routinely covered in dental implant textbooks. It covers demographics, the need for dental implants, and the business of dental implants. It is a total tutorial of the field, not just a how to do it book. The chapter on legal matters is updated and well documented. The chapter on essential systems for team training is cutting edge in its approach. It is evident that in this book, as with his prior publications, Dr. Babbush derives personal pleasure from passing on what he has learned. When a distinguished lecturer, author, and scientist with more than 40 years of clinical experience in the field of dental implants writes a fifth book, a summary, all inclusive text, any restorative dentist should stop what they are doing and begin turning the pages. From the earliest days of modern implantology when blade implants were first attempted, Dr. Babbush has kept striving for the elusive goal of tooth replacement and reconstructive restorative surgery to optimize implant placement. He has frequently been a leader in applying new techniques for standardized application. One thing mastered in this updated second edition is the treatment planning concept, making sure that clinicians work in concert with each other to optimize desired treatment goals. The core values Dr. Babbush so aptly expresses is that care should be taken before one begins, that the surgeon should never work alone but in collaboration with colleagues, that the highest available technology should be employed, and that the safety of the patient be observed. Clinicians in the field of implant dentistry will gain clinical knowledge, if not wisdom, in the study of this timely book. I first met Dr. Charles Babbush in Paris, France. It was 1972, and he was serving as program chairman for ICOI’s first World Congress. We had taken very different educational paths. I had mentored in surgical prosthodontics with Dr. Isiah Lew from New York, and Dr. Babbush had pursued classical oral and maxillofacial surgery training. Together we experienced the painful birthing, initial rejection, and beginning acceptance of dental implants by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), then by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1978, and ultimately by the American Dental Association (ADA). Simply stated, however, no matter how many people have made significant contributions to the field of oral and facial implant therapy, few people can claim themselves as an active participant in clinical treatment, research, and education for more than four decades so thoroughly as Dr. Babbush. For bringing us his wealth of experience in his latest text, Dental Implants: The Art and Science, Second Edition, he deserves the gratitude of our profession, specialty groups as well as generalists, researchers, laboratory technicians, and auxiliaries—in essence the total dental team. What is not communicated in this text is the extent to which Dr. Babbush has been a significant force in worldwide implant education, returning again and again to numerous countries, venues, implant societies, and universities to introduce, modify, and ultimately reinforce his concepts. The result is much needed research-based information. Few people can assemble and work with authors from all areas of dentistry related to oral and facial implant therapy and organize his own and their contributions in such a way that the reader is enthralled. This is a text, which for its completeness and excellence, is to be read, savored, and then reread. My sincere congratulations to all contributors. Jerold S. Goldberg, DDS Dean School of Dental Medicine Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, Ohio Ole T. Jensen, DDS, MS Assistant Clinical Professor University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan Kenneth W.M. Judy, DDS, PhD (hc, multi), FACD, FICD Co-Chair, International Congress of Oral Implantologists New York, New York xii The term “pioneer” is reserved for a few select individuals in the world of implant dentistry. I was honored to have one of these individuals, Professor P.I. Brånemark, author a forward in several books I wrote on osseointegration, and I am honored to provide these remarks for another true pioneer, Dr. Charles Babbush, as an introduction to this remarkable text. Their early careers could not have been more divergent, one doing medical orthopedic research in Sweden, while the other was evolving early implant dentistry as a practicing oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Both found a common ground in the early 1980s with the introduction of osseointegration to North America, and both have continued to make significant contributions over a nearly unprecedented period of four decades. This textbook, Dental Implants: The Art and Science, Second Edition, is a perfect example. It is rare today to find a seminal publication of any kind in the field of implant dentistry, but given the scope of topical exposure, the international reputa- Foreword tions of the chapter contributors, and Dr. Babbush’s personal writings and insight, this book certainly qualifies as one of those rare contributions to the field. If you can put “enjoyable” and “required” reading in the same sentence, it would certainly apply here. Anyone with an interest in implant dentistry at any level, from those just starting out, to surgeons, restorative dentists, assistants, hygienists, and lab technicians, will find take-home value in every chapter. My congratulations to Dr. Babbush and to his co-authors for providing us with this remarkable text, and my gratitude to them for providing us with an encyclopedic reference source in one volume. I can’t wait for the third edition. Stephen M. Parel, DDS Prosthodontist Private Practice, Implant Surgery Dallas, Texas P R E F A C E The year 2010 is the 48th year since my graduation from the University of Detroit, School of Dentistry. Additionally, it is the 42nd year since I placed my first implant (a Blade-Vent) in the left maxillary second bicuspid first molar region of a 20-something female patient. To the best of my knowledge, that implant survives to this day somewhere in California. I never cease to be amazed by the survival of implant cases which I did 20 … 25 … 30 … 35+ years ago using almost primitive designs, materials, techniques, and concepts of surgery and restorative procedures. Throughout my career, I have continually sought out the best materials, designs, and technology in order to improve upon the outcome, prognosis, and survival of these cases. My first endeavor encompassed the blade-vent concept; from there I moved on to the mandibular full-arch subperiosteal implant as well as to vitreous and pyrolyte carbon, aluminum oxide, ramus frame, mandibular staple bone plate, and more advanced designs of the blade-vent implant. The next step in my career took me into more contemporary times with the TPS Swiss Screw and the original design of the ITI Strauman concept implants. This was followed by a strong position using twostage osseointegrated root form implants of the IMZ design followed closely by Steri-Oss and Frialit screw-type designs. The NobelReplace Implant System came next, and ultimately, I have settled on the NobelActive Implant System, which has led me to the most incredible surgical prosthetic outcomes in the most challenging of patients and anatomical situations. As I entered this incredible phase of my practice, I have utilized the latest and greatest techniques as well as the most cutting-edge technology. The latest generation of the cone beam CT scanner is used with every patient. This helps us to accurately determine bone quality and bone quantity. It also provides for the visualization of interactive 3-D modeling, which allows for the development of surgery and prosthetic treatment plans before ever entering the operating room as well as the fabrication of surgical guides when indicated. The use of digital periapical and panoramic imaging has reduced radiation exposure, improved imagery capability and allowed for computer-to-computer Internet messaging, which has helped to broaden the exchange of information and communication. Consolidation of the number of procedures necessary to achieve preliminary immediate reconstruction for the patient, as well as the definitive prosthetic results, has made a significant impact on patient acceptance and long-term results. Implants that we are currently using offer a tremendous increase in initial stability, which allows not only placement after extraction but also immediate loading in a vast majority of cases. As previously stated, with all of these concepts we will be able to provide improved treatment to the public, who, in many instances, are in a state of end-point crippling disease. The procedures include, but are not limited to, the elimination of chronic pain, neurological deficit, and various levels of dysfunction. These individuals may also be the victims of terrible social rejection, which includes loss of self-confidence and self esteem resulting from the overshadowing aspects of severe advanced atrophy of the maxillofacial skeleton. As we enter this new millennium and its accompanying realm of technological advances, it is evident that an individual who has the need, time, desire, and interest to have this reconstruction can certainly be brought back into the mainstream of function, improved aesthetics, alleviation of pain, and elimination of the terrible emotional and psychiatric depression. We know that the quality of care, along with improved technologies, will enable those of us in the healthcare field to reconstruct the oral mechanisms for a greater number of the population with higher levels of efficacy and improved longterm survivals than ever before. Charles A. Babbush xiii A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S Once again, in this, my fourth textbook, I want to thank my office staff members who continue, to contribute on a daily basis to my work: Sherry Greufe, Ella Mae Shaker, Mary Napp, Lori Ruiz-Bueno, Pat Zabukovec, and Faith Drozin, who have been with me for decades. Additionally, I wish to thank the newer members of our clinical staff: Jennifer Sanzo, Kim Middleton, Rebecca Bowman, and Wendy Rauch as well as our outstanding laboratory technicians, Paul Brechelmacher and Alan McGary. A special thank you goes to Ella Mae Shaker for the massive amount of typing for this book over the last several years. Over the past 42 years many colleagues from near and far have collaborated with me in this work. They have shared their knowledge and experience, as well as their patients, in numerous instances, and for all of this I think of you often and thank you for your participation and support. The man who actually gave me a few implants in 1968 in order to carry out my original blade-vent research is Dr. Jack Wimmer, President of Park Dental Research in New York City. Over the years he has continued to be a colleague, a mentor, and, most of all, my friend. For this, I am greatly indebted and thank you for all you have done for me, as well as the field of implant dentistry. The staff of Elsevier has contributed, as usual, their most professional support, advice, and hard work related to this book. From the cover through the editing and layout to the last page John Dolan, Executive Editor, has been the all-time supreme professional, and in a similar manner, so have Courtney Sprehe, Senior Development Editor and Rachel McMullen, Senior Project Manager. The amazing group of contributors who have come together to share their extensive knowledge, talent, skill, and experience rivals and, I believe, surpasses any work yet published in this field. For all of them we lift our collective hats and appreciation for their efforts. xiv I wish to thank an amazing group of individuals who have entered my life and career in the past several years. They comprise the group at ClearChoice Dental Implant Centers in Denver, Colorado. Dr. Don Miloni had the original vision and concept and he bid Mr. Steve Boyd to join him to create the original business entity, which has expanded to now include a wonderful group of people: Margaret McGuckin, Larry Deutsch, Dan Christopher, John Walton, and Bobby Turner, just to name a few. I thank them for their leadership, business experience, friendship, and corporate culture. In the same concept, I wish to thank ClearChoice for bringing Dr. Gary Kutsko, Prosthodontist, and myself together in the Cleveland ClearChoice Center. He is creative, innovative, and continues to make our work together a joy on a daily basis. Dr. John Brokloff has also joined our staff as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. It is truly a pleasure to have him participate, and I know our staff and patients have all enjoyed his technical skill and wonderful patient management. At this time I want to thank Jack Hahn, Jack Krauser, and Joel Rosenlicht for joining me and sharing this work with you in this book. They bring over 125 years of combined clinical practice, research, and education to Dental Implants: The Art and Science, Second Edition. After all, we have had the same common goals over all these years of advancing the field of implant reconstruction for our patients as well as colleagues. Lastly, I wish to thank my distinguished colleagues and friends: Dean Jerold Goldberg, Drs. Steven Parel, Ole Jensen, Mark Adams, and Ken Judy, who responded to my invitation to write the forwards for this book in such an eloquent manner. All of you have made significant contributions to me, to this book and to the field of implant reconstruction in order to continue to be able to change lives on a daily basis. Charles A. Babbush C O N T E N T S CHAPTER 1: The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants 1 L. Jackson Brown, Charles A. Babbush CHAPTER 2: The Business of Implant Dentistry 17 Bob Salvin CHAPTER 3: Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice 25 Samuel M. Strong, Stephanie S. Strong CHAPTER 4: Dental Risk Management 40 Richard J. Rymond, Ronald A. Mingus, Charles A. Babbush CHAPTER 5: Master Planning of the Implant Case 60 Charles A. Babbush, Joel L. Rosenlicht CHAPTER 6: Dental Implant Therapy for Medically Complex Patients 86 Adi A. Garfunkel CHAPTER 7: Surgical Anatomical Considerations for Dental Implant Reconstruction 98 Celso Leite Machado, Charles A. Babbush, Arthur L. Rathburn CHAPTER 8: Contemporary Radiographic Evaluation of the Implant Candidate 110 Joel L. Rosenlicht, Ryaz Ansari CHAPTER 9: Bone: Present and Future 124 Cameron M.L. Clokie, George K.B. Sándor CHAPTER 10: The Use of CT/CBCT and Interactive Virtual Treatment Planning and the Triangle of Bone: Defining New Paradigms for Assessment of Implant Receptor Sites 146 Scott D. Ganz CHAPTER 11: Peri-implant Soft Tissues 167 Eric Rompen, Eric Van Dooren, Konstantin D. Valavanis CHAPTER 12: Membrane Barriers for Guided Tissue Regeneration 181 Jack T. Krauser, Barry Kyle Bartee, Arun K. Garg CHAPTER 13: Contemporary Subantral Sinus Surgery and Grafting Techniques 216 Dennis G. Smiler, Muna Soltan, Michelle Soltan Ghostine CHAPTER 14: Inferior Alveolar Nerve Lateralization and Mental Neurovascular Distalization 232 Charles A. Babbush, Joel L. Rosenlicht CHAPTER 15: Graftless Solutions for Atrophic Maxilla 251 Edmond Bedrossian xv xvi Contents CHAPTER 16: Complex Implant Restorative Therapy 260 Evan D. Tetelman, Charles A. Babbush CHAPTER 17: Intraoral Bone Grafts for Dental Implants 276 Craig M. Misch CHAPTER 18: The Use of Computerized Treatment Planning and a Customized Surgical Template to Achieve Optimal Implant Placement: An Introduction to Guided Implant Surgery 292 Jack T. Krauser, Joel L. Rosenlicht CHAPTER 19: Teeth In A Day and Teeth In An Hour: Implant Protocols for Immediate Function and Aesthetics 300 Thomas J. Balshi, Glenn J. Wolfinger, Stephen F. Balshi, James R. Bowers, J. Neil Della Croce CHAPTER 20: Extraction Immediate Implant Reconstruction: Single Tooth to Full Mouth 313 Charles A. Babbush, Jack A. Hahn CHAPTER 21: Immediate Loading of Dental Implants 340 Joel L. Rosenlicht, James A. Ward, Jack T. Krauser CHAPTER 22: Management of Patients With Facial Disfigurement 355 Marcelo Ferraz de Oliveira, Loretta De Groot Oliveira CHAPTER 23: The Evolution of the Angled Implant 370 Stephen M. Parel CHAPTER 24: Implants for Children 389 Richard A. Kraut CHAPTER 25: Piezosurgery Related to Implant Reconstruction 403 Tomaso Vercellotti CHAPTER 26: A New Concept of Tapered Dental Implants: Physiology, Engineering, and Design 414 Ophir Fromovich, Benny Karmon, Debora Armellini CHAPTER 27: The All-on-4 Concept 435 Paulo Maló, Isabel Lopes, Miguel de Araújo Nobre CHAPTER 28: Laboratory Procedures as They Pertain to Implant Reconstruction 448 Sven Jesse CHAPTER 29: Complications and Failures: Treatment and/or Prevention 467 Charles A. Babbush CHAPTER 30: Hygiene and Soft Tissue Management: Two Perspectives 492 Jack T. Krauser, Lynn D. Terraccianao-Mortilla, Jan LeBeau Uploaded by dentalebooksfree.blogspot.com `Ìi`ÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊ`iÊÛiÀÃÊvÊ vÝÊ*ÀÊ* Ê `ÌÀÊ /ÊÀiÛiÊÌ ÃÊÌVi]ÊÛÃÌ\Ê ÜÜÜ°Vi°VÉÕV° Ì Uploaded by dentalebooksfree.blogspot.com `Ìi`ÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊ`iÊÛiÀÃÊvÊ vÝÊ*ÀÊ* Ê `ÌÀÊ /ÊÀiÛiÊÌ ÃÊÌVi]ÊÛÃÌ\Ê ÜÜÜ°Vi°VÉÕV° Ì This page intentionally left blank L. Jackson Brown Charles A. Babbush C H A P T E R 1 THE FUTURE NEED AND DEMAND FOR DENTAL IMPLANTS This chapter reviews the present and probable future need and demand for dental implants. A dental implant is defined as an artificial tooth root replacement and is used to support restorations that resemble a natural tooth or group of natural teeth (Figure 1-1).1 Implants can be necessary when natural teeth are lost. When tooth loss occurs, masticatory function is diminished; when the underlying bone of the jaws is not under normal function it can slowly lose its mass and density, which can lead to fractures of the mandible and reduction of the vertical dimension of the middle face. Frequently, the physical appearance of the person is noticeably affected (Figure 1-2).1 To understand the growth in the use of dental implants in recent years and their probable future need and demand, several topics require review. The background section of this chapter provides a general description of tooth loss and its consequences, the technical options that are available for replacing missing teeth, and the circumstances in which each option is appropriate. Following the general background, the discussion section systemically addresses the various factors that influence the need and demand for tooth replacement. The final sections of the chapter assess the recent growth in dental implants and their likely trend for the future. Background Tooth Loss Humans have lost their natural teeth throughout history. Teeth are lost for a variety of reasons.2-4 In primitive societies most teeth are lost as the result of trauma. Some are intentionally removed for sacred rituals or for cosmetic reasons (Figure 1-3). Oral diseases, mostly dental caries and periodontal disease, have attacked human dentitions throughout mankind’s long existence. In primitive cultures, both extant and past, periodontal disease is known to have occurred. Signs of periodontal bone loss are often prevalent in the fossil records and are detected by physical and radiographic examination in individuals from existing primitive cultures. Dental caries, the most common dental disease of recent centuries, occurred in these cultures but was not as prevalent as it became in modern times. In contrast to primitive societies, oral diseases and their sequelae have become the predominant cause of tooth loss in modern societies of the 20th and 21st centuries. Trauma still plays an important part in tooth loss, but less than that of oral diseases. A major reason for the increase in the role of disease in tooth loss in modern societies is the expanded proportion of refined sugar and other cariogenic food items that make up the diets of industrialized societies.5 This change in diet was a major contributing factor in an epidemic of dental caries during the first three quarters of the 20th century. The epidemic continued unabated until the deployment of modern preventive dentistry beginning around the middle of the 20th century. This epidemic of caries, along with more available professional dental care, led to a concomitant increase in the extraction of teeth by dental health professionals. Partial tooth loss was almost ubiquitous. Total tooth loss, edentulism, was not 1 2 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants uncommon among young adults and became the predominant condition among elderly populations. More detail on the past and likely future trends in tooth loss are provided in the last section of this chapter. Options for Replacement of Lost Teeth When a tooth is lost, the individual and the dentist face two choices. The first choice is: should I replace the missing tooth? Crown Crown Gum Gum Bone Bone Root Implant The second is: what is the best way to replace it? Although these decisions may seem sequential, they are interrelated in important ways. The technical options available can influence the decision to replace a tooth, and modern science has produced more and better options for tooth replacement in many circumstances.6-8 The age and general health of the patient are critical. The condition of the remaining dentition, its configuration in the mouth, and its periodontal support are very important aspects of the decision to replace.1,6 Finally, the relative cost of options can play a role, but should not be dispositive for a treatment plan. In making these decisions, the dentist and patient must evaluate all of these factors to reach the best treatment for a particular patient.5 A number of restorative options for the treatment of missing teeth are recognized as accepted dental therapy, depending on particular circumstances the patient presents. These include: 1. Tissue-supported removable partial dentures9 (Figure 1-4) 2. Tooth-supported bridges (Figure 1-5)10 3. Implant-supported teeth (Figure 1-6)8 Likewise, there are two basic options for replacing teeth in a completely edentulous arch: 1. Tissue-supported removable complete dentures11 (Figure 1-7) 2. Implant-supported over-dentures12,13 (Figure 1-8) All these therapies have their indications for use; a brief review of their indicators, strengths, and limitations follows. Tissue-Supported Prostheses: Partial and Complete Dentures Figure 1-1. Comparison of natural tooth and crown with implant and crown. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) A Removable dentures, whether partial or complete, are supported by the bone of the jaw and the soft oral mucosa covering the jaw.9,11 Removable partial dentures frequently are held in place by metal clasps that clip onto teeth or by precision attachments that insert into specially designed receptacles on B Figure 1-2. A and B, This patient has lost all of her upper and lower teeth and has a moderate amount of subsequent jaw shrinkage as well as a decrease in facial structure both in the frontal and lateral view. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) 3 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants A B C Figure 1-3. A, A wrought-iron tooth implant in the upper jaw of an ancient warrior in Gaul. B, A radiograph of the metal implant. C, A typical warrior of Gaul. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) R Figure 1-4. A typical collection of prosthetic devices, including flippers, removable partial dentures, and full dentures. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) L Figure 1-5. A panoramic radiograph demonstrating three-unit bridges in the left maxilla and in the right posterior aspect of the mandible. 4 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants A B Figure 1-6. A, A panoramic radiograph with a single tooth implant reconstruction in the left mandible. B, A panoramic radiograph demonstrating full arch, maxillary, and mandibular reconstruction with fixed prosthetic appliances. Figure 1-7. Many dentures become so unsatisfactory they are left in a glass of water. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) artificial crowns placed on teeth adjacent to the space created by the missing tooth or teeth. Patients need to take these removable partial prostheses in and out regularly for cleaning after eating and at night. Removable prostheses have a long history as a practical answer to partial and complete tooth loss. For a long time they were the only option available for complete-arch edentulism and partial edentulism without posterior supporting teeth. A major advantage of tissue-supported prostheses compared with tooth-supported prostheses or dental implants is that they are less invasive and require less sacrifice of oral tissues to place in the mouth. However, they have distinct problems for the individual who wears them. Tissue-supported prostheses continually stress the oral tissues.14 Over time, the weight-bearing stress Figure 1-8. A model of a four-implant connector bar with an overdenture and internal clip fixation. (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.) caused by mastication—and to a lesser extent, other activities such as bruxism—can cause the underlying bone to resorb, reducing the bony mass of the jaws. If this bony resorption is extensive enough it can lead to fracture of the mandible. This bony pathology frequently is accompanied by local mucosal lesions created by the prosthesis. Sometimes the oral tissues cannot continue to support neither an existing tissue supported prosthesis nor a new prosthesis to replace the existing one (Figure 1-9). Tooth-Supported Prostheses: Fixed Bridges Tooth-supported fixed prostheses (bridges) rely on the adjacent teeth for support. The teeth next to the missing tooth Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants Figure 1-9. A panoramic radiograph demonstrating severe advanced atrophy of both the maxilla and mandible. space(s) are anatomically prepared to receive, in most cases, a porcelain, gold, or porcelain-fused-to-gold crown.10 After the teeth are prepared and a negative impression is taken, the fixed prosthesis is constructed by a dental laboratory. When the finished bridge is returned to the dentist, it is cemented onto the prepared abutment teeth. This prosthesis is fixed in place; it does not come in and out. It relies on the integrity of the adjacent teeth for support. Fixed prostheses also have a long history in dental practice. The stresses of mastication are passed down through the support structure to the abutment teeth. These tissues are capable of absorbing the stress of mastication because that is part of their natural function. However, the longer the span of replaced teeth, the greater the stress placed on the abutment teeth. In addition, the crowned abutment teeth are at risk for caries under the crown and along its margin with the tooth structure. If the periodontal health of the abutment teeth deteriorates, the entire support for the fixed bridge can be compromised. Bone-Supported Prostheses: Dental Implants The final method of tooth replacement is the dental implant,8 which is a replacement for the root of a tooth. The implant is placed where the root of the missing tooth used to be. The replacement root is then used to attach a replacement tooth. Like the other options, dental implants are used to replace missing teeth and restore masticatory function to an individual’s dentition. The major types of dental implants are osseointegrated and fibrointegrated implants.8 Earlier implants, such as the subperiosteal implant and the blade implant, were usually fibrointegrated. The most widely accepted and successful implant today is the osseointegrated implant. Examples of endosseous implants (implants embedded into bone) date back over 1350 years. While excavating Mayan burial sites in Honduras in 1931, archaeologists found a fragment of mandible with an endosseous implant of Mayan origin, dating from about 600 ad (Figure 1-10). Widespread use of osseointegrated dental implants is more recent. Modern dental implantology developed out of the 5 Figure 1-10. A Mayan lower jaw, dating from 600 ad, with three tooth implants carved from shells. (From the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.) landmark studies of bone healing and regeneration conducted in the 1950s and 1960s by Swedish orthopedic surgeon P. I. Brånemark.15 This therapy is based on the discovery that titanium can be successfully fused with bone when osteoblasts grow on and into the rough surface of the implanted titanium. This forms a structural and functional connection between the living bone and the implant. A variation on the implant procedure is the implant-supported bridge, or implant-supported denture. Today’s dental implants are strong, durable, and natural in appearance. They offer a long-term solution to tooth loss. Dental implants are among the most successful procedures in dentistry.16-20 Studies have shown a 5-year success rate of 95% for lower jaw implants and 90% for upper jaw implants. The success rate for upper jaw implants is slightly lower because the upper jaw (especially the posterior section) is less dense than the lower jaw, making successful implantation and osseointegration potentially more difficult to achieve. Lower posterior implantation has the highest success rate of all dental implants. Dental implants are less dependent than tooth- or tissuesupported prostheses on the configuration of the remaining natural teeth in the arch. They can be used to support prostheses for a completely edentulous arch, for an arch that does not have posterior tooth support, and for almost any configuration of partial edentulism with tooth support on both sides of the edentulous space. Additionally, dental implants may be used in conjunction with other restorative procedures for maximum effectiveness.21 For example, a single implant can serve to support a crown replacing a single missing tooth. Implants also can be used to support a dental bridge for the replacement of multiple missing teeth, and can be used with dentures to increase stability and reduce gum tissue irritation. Another strategy for implant placement within narrow spaces is the incorporation of the mini-implant. Mini-implants may be used for small teeth and incisors. Modern dental implants are virtually indistinguishable from natural teeth. They are typically placed in a single sitting 6 but require a period of osseointegration. This integration with the bone of the jaws takes anywhere from 3 to 6 months to anchor and heal.22,23 After that period of time a dentist places a permanent restoration for the missing crown of the tooth on the implant. Although they demonstrate a very high success rate, dental implants may fail for a number of reasons, often related to a failure in the osseointegration process.24-30 For example, if the implant is placed in a poor position, osseointegration may not take place. Dental implants may break or become infected (like natural teeth) and crowns may become loose. Dental implants are not susceptible to caries attack, but poor oral hygiene can lead to the development of peri-implantitis around dental implants. This disease is tantamount to the development of periodontitis (severe gum disease) around a natural tooth. Dental implant reconstruction may be indicated for tooth replacement any time after bone growth is complete. Certain medical conditions, such as active diabetes, cancer, or periodontal disease, may require additional treatment before the implant procedure can be performed. In some cases in which extensive bone loss has occurred in a jaw due to periodontal disease, implants may not be advised. Under proper circumstances, bone grafting may be used to augment the existing bone in a jaw prior to or in conjunction with placement. Need and Demand for Tooth Replacement Two general approaches are available to estimate the number of dental implants that will be placed.2,3 The first is a needsbased approach based on an estimation of unmet needs in a population. Workforce assessment starts with estimates of oral health personnel required to treat all oral disease or a specified proportion of that disease. A variation on this approach is to adjust those estimates downward based on the anticipated utilization of dental services by the populace. The second approach is a demand-based approach that uses the demand for dental services as the starting point to estimate required oral health personnel. This approach relies on economic theory to identify important factors that influence supply and demand for dental services. Future trends for these factors are used to forecast workforce requirements. A clear distinction must be drawn between demand and unmet need for services in order to understand future access to care and what interventions are likely to be effective in improving access to care for some subpopulations. The Concept and Measurement of Need Need for care generally arises because of the existence of untreated disease. The scientific basis for efficacious therapy must also exist.2,3 Untreated disease in affluent societies usually coexists, with the majority of patients receiving the highest quality of care. In less affluent societies, a preponderance of disease may go without therapeutic intervention. The needbased approach uses normative judgments regarding the amount and kind of services required by an individual in order Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants to attain or maintain some level of health. The level of unmet need in a society is usually determined from health level measurements based on epidemiological or other research identifying untreated dental disease. The underlying assumption is that those in need should receive appropriate care. Once the level of need is determined, the quantity of resources is then determined based on matching unmet need with appropriate care. Evaluation of unmet need is important for identifying populations in which access, for whatever reason, may be a problem. Epidemiological and health research in dentistry are designed to identify population-based dental care problems such as segments of the population with unmet need. An understanding of the economic and social conditions surrounding such groups, their reasons for not seeking professional dental care, and the role that price plays in determining effective demand helps analysts identify weaknesses in the existing care system and establish a foundation for effective remedies. In addition, need assessment requires a normative judgment as to the amount and kind of services required by an individual to attain or maintain some level of health. Fundamentally, the need assessment focuses on which, and how many, services should be utilized. In almost all circumstances, this will differ from the services actually utilized. Oliver, Brown, and Löe31,32 provide a thorough discussion of dental treatment needs as well as a review of studies that estimate dental treatment needs. The Concept and Measurement of Demand In the United States, professionally trained dentists provide most dental services. These services are delivered through private markets shaped by supply and demand.2,3 Under a market system, dental services are provided to those who are willing and able to pay the dentist’s standard fee for the services rendered. This makes an assessment of demand for dental services essential for understanding the actual delivery of care. A clear distinction must be drawn between demand and unmet need for services in order to understand future access to care and what interventions are likely to be effective in altering access to care for some subpopulations. In assessing demand, the consumer is the primary source driving the use of dental services. The demand for dental care reflects the amount of care desired by patients at alternative prices. The quantity of dental services desired is negatively related to price, and changes in the quantity of care demanded are significantly responsive to changes in dental fees. Other factors can influence the level of demand, including income, family size, population size, education level, insurance coverage, health history, ethnicity, age, and other conditions. Demand-related policies can be used to alter market conditions and the distribution of care. Supply, as well as demand, influences the ability of the dental workforce to adequately and efficiently provide dental care to a U.S. population growing in size and diversity. The capacity of the dental workforce to provide care is influenced by enhancements in productivity, numbers of dental health 7 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants personnel, and dental workforce demographic and practice characteristics. The full impact of these changes is difficult to predict. A limitation of the market delivery system is that individuals with unmet needs who are unable or unwilling to pay the provider’s fee generally do not effectively demand care from the private practice sector. Individuals often cannot express their demand for care because of their economic disadvantage. Stated plainly, these people are poor and cannot afford expensive dental services. From a societal perspective, it may be very desirable that these individuals have full access to dental services, including the replacement of their missing teeth. To provide that needed care, the demand for care among the economically disadvantaged must be supported in one of three ways: through pro bono care offered by dentists, through institutional philanthropic funding, or through public funding. If public funding for dental services, including tooth replacement, is meager, then effective demand for those services will also remain meager.2,3 Factors that Affect Need and Demand for Tooth Replacement The factors that affect the need and demand for dental implants can be described as macro (large-group) factors and individual factors. Macro factors are so named because, though they affect individuals, their cumulative impact (for the entire country or large sections of the country) is most relevant for the total number of dental implants that will be needed and demanded. These macro factors include (1) overall population grown and demographics (age, gender, and racial/ethnic profile), (2) growth in disposable per capita income and improvement in educational levels, (3) the extent and severity of oral diseases that can result in tooth loss, and (4) tooth loss itself. Individual factors influence whether or not a particular person will (1) experience a missing tooth, (2) decide whether to have a replacement or leave the space vacant, and (3) choose a dental implant or one of the alternatives as the replacement. Macro Factors Population Growth and Composition Table 1-1 provides estimates of the United States population by age in 2000, and projects population through 2050. Total TABLE 1-1 population has increased by about 50 million since 1980 and is expected to grow by almost 50% between 2000 and 2050. Almost one half of that growth will occur in three states: California, Florida, and Texas.33-35 Along with an increase in size, the population will also experience significant changes in its distribution by age. As a percent of the total, the elderly comprise 12.4% of the total population. By 2050 the elderly will make up 20.6% of the total population. Baby-boomers are another important component of the U.S. population. Born between 1945 and 1964, the leading edge of baby-boomers was in their mid-30s in 1980, mid-50s in 2000, and will be in their mid-70s in 2020 (Figure 1-11). This change in the age distribution of the nation’s population is important in assessing the potential need for dental services. Different age groups require different types of dental services. Older individuals require more replacement restorations and replacement of teeth. The majority of endodontic services are performed on individuals between the ages of 35 and 74 years. As of 2000, the youngest of the baby-boomers were in their late 30s. The most important time of life for expenditures for dental services has always been between 45 and 64 years of age. The population group 45 to 54 years of age has experienced substantial growth since 1980, especially during the past 10 years. This age cohort will continue to increase in numbers through 2010 when it will begin to decline as the youngest babyboomers age out of this age group and are replaced by the numerically smaller generation that follows them. In contrast, the number of people aged 55 to 64 years has increased only slightly since 1980 but will experience marked growth during the next 20 years with the arrival of the bulk of the baby-boomers. An age group with a somewhat lower utilization, but a high disease level, is the 65 years and older age group. This age group is expected to increase by more than 50% between 2000 and 2020. Utilization of dental services by this age group will increase if, as predicted, this age group in 2020 retains more of their teeth than did previous generations and/or continues working longer. Changes in the population’s racial and ethnic composition also are expected to be important. For example, the Hispanic population will increase from 12.6% in 2000 to 24.4% of the total population by 2050. The white, non-Hispanic Projected growth and changes in U.S. population (in thousands), 2000-2050 Total Population 5 to 19 Years Old 65 Years and Older White, not Hispanic Black Alone Asian Alone 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Total change 282,125 61,331 35,061 195,729 35,818 10,684 308,936 61,810 40,243 201,112 40,454 14,241 335,805 65,955 54,632 205,936 45,365 17,988 363,584 70,832 71,453 209,176 50,442 22,580 391,946 75,326 80,049 210,331 55,876 27,992 419,854 81,067 86,705 210,283 61,361 33,430 48.8% 32.2% 147.3% 7.4% 71.3% 212.9% From the U.S. Census Bureau, 2004. 8 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants 12 10.8 10 9.2 8.5 8 3.9 2.8 –4 A 55–59 50–54 45–49 40–44 35–39 30–34 25–29 20–24 15–19 10–14 5–9 0–4 –2 0.7 75+ 0.7 –0.9 –2.4 –0.5 0 2.0 1.9 2 70–74 2.4 65–69 2.8 60–64 Millions 4 6.6 6.1 6 Age Group –6 12 10.0 10 8.3 8.1 8 3.7 2 1.2 –6 75+ 70–74 65–69 60–64 55–59 50–54 45–49 40–44 35–39 30–34 25–29 20–24 –4 B 2.9 2.2 1.6 6.0 –0.5 –1.8 0.0 15–19 –2 1.3 10–14 0 3.1 2.1 5–9 4 5.3 0–4 Millions 6 Age Group Figure 1-11. A, Change in the U.S. population by age group from 1980 to 2000. B, Projected change in the U.S. population by age group from 2000 to 2020. (From the U.S. Census Bureau, 2005.) population is expected to decrease from 69.4% to 50.1% of the total. These shifts in the age and racial/ethnic composition of the U.S. population probably will be concentrated in selected regions and states. Total population growth is another important factor in determining the growth of dental implants: the larger the population, the more teeth are at risk to be lost. Holding others factors constant, a larger population generates more potential need for implants. Moreover, the loss of teeth is cumulative and nonreversible. For a particular birth cohort, the number of missing teeth will never decline as these individuals age. Although not biologically inevitable, the number of missing teeth in a group has always increased as the group ages. Growth in Per Capita Income Despite periods of slow growth or economic contraction, the U.S. economy has grown steadily since the formation of the nation. The post–World War II period, particularly, has been a period of rising affluence for Americans. Using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA),36-39 trends in real disposable per capita personal income from 1960 to 2005 are presented in Figure 1-12. In real terms, disposable per capita personal income in the United States increased from $9,735 in 1960 to $27,370 in 2005, representing an overall increase of 180% and an average annual growth of 4.0% (Figure 1-12). All parts of the United States shared in the growing affluence. In 1929 the richest state in the union was New York 9 30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 9,735 11,594 13,563 15,291 16,940 17,217 17,418 17,828 19,011 19,476 19,906 20,072 20,740 21,120 21,281 21,109 21,548 21,493 21,812 22,153 22,546 23,065 24,131 24,564 25,472 25,697 26,235 26,594 27,232 27,370 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 5,000 Figure 1-12. Real disposable per capita income, 1960-2005. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.) (with per capita income of $9717). Figure 1-13, A shows how the other states compared to New York in that year. The poorest state at the time was South Carolina, where per capita income was $2282. The richest state (New York) was more than four times richer than the poorest state (South Carolina). Moreover, 20 of the 48 states had incomes that were less than 50% of the richest state. By the year 2003 a lot had changed, including the distribution of income across the states. Figure 1-13, B shows that the gap between the richest state (Connecticut, $40,990) and the poorest state (Mississippi, $22,262) has declined—the ratio in 2003 was 1.84. Moreover, many states make less than 50% of the richest state’s income. So, while the rich have gotten richer—real per capita income for New York (the richest state in 1929) rose by a factor of 3.5—the poor have gotten richer at a faster rate—real per capita income in South Carolina (the poorest state in 1929) increased by a factor of 10. These data show that expansion of discretionary income has augmented the U.S. population’s capacity to buy expensive discretionary items such as tooth replacement prostheses, including dental implants. The rising living standards are widespread, affecting all parts of the United States. Improvement in Educational Attainment Education is an important determinant of the demand for dental services. Logistical models of the likelihood of a dental visit during the past year show that education level may be the strongest determinant of demand after controlling for income and other variables. As shown in Figure 1-14, the percentage of the U.S. population with at least a high school diploma doubled from 41.1% in 1960 to 84.1% in 2000. The increase in the percentage of the population with a college degree or higher tripled from 7.7% in 1960 to 25.6% in 2000.36-38 Figure 1-15 shows differences in the percentages of people with a college degree or more by race and Hispanic origin. The annual rate of growth for whites between 1995 and 2002 was 1.8%; for African Americans, 3.68%; and for Hispanics, 2.56%. If these higher growth rates for the Hispanic population continue, the educational gap between whites and Hispanics will be reduced. Note that the Hispanic population is not a homogeneous group with respect to dental service demand. Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans) report significant differences in the percentage of members who had a dental visit during the past year. The overall rise in educational level is very important because educational attainment is such a potent predictor of the use of dental services, especially big-ticket items such as dental implants. The remaining disparities in educational attainment by race and ethnicity also correlate with the differences in demand for dental care among these groups. If these education disparities are narrowed in the future, it may indicate a broader market for dental implants because economic disadvantage, educational attainment, and tooth loss are all correlated and are together extremely powerful predictors of the use of and expenditures for dental services. Trends in Dental Caries and Tooth Loss Dental caries, which creates a biological need for care, has been the primary foundation of the demand for dental services in modern times. The prevention and treatment of caries and its sequelae are large components of demand. Among adults, and 61,397 A B SC MS AZ AL NC GA TN ND KY NM LA SD VA OK WV TX ID FL KS UT IA NE MT MN AK ME IN MO CO VT OR WY WI NH WA MD OH PA MI NV RI MA NL IL CA CT DE NY DC 0 60000 50000 40000 30000 0 0 267 279 305 320 328 343 374 377 388 404 410 416 432 452 459 476 500 517 528 547 572 586 590 594 597 598 604 618 630 630 665 669 670 685 739 769 771 773 791 400 28,527 29,293 30,090 30,100 30,604 30,787 31,048 31,703 32,401 32,900 33,145 33,152 33,373 33,416 33,663 33,962 33,984 34,342 34,509 34,796 34,910 35,027 35,664 35,770 35,955 36,189 36,241 36,483 37,006 37,446 38,316 38,740 39,060 39,649 39,712 39,934 40,058 40,919 40,969 41,019 41,062 41,444 41,561 41,580 46,646 46,664 47,038 49,142 49,238 54,984 600 0 800 MS WV UT AR NM KY SC ID AL AZ MT IN TN GA NC ME MO MI OH IA OK OR SD LA ND NE WI KS TX VT FL PA HI NV RI AK DE IL NM CO WA NH VA CA MD NY WY MA NJ CT DC 1000 868 876 907 920 949 993 1,027 1,031 1200 1,151 1400 1,273 10 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants 200 70000 20000 10000 Figure 1-13. A, The variation in per capita income by state, 1929. B, The variation in per capita income by state, 2007. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.) 11 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants 60% 5% 0% 2000 Figure 1-15. Percent of the U.S. population 25 years and older who were college graduates or had advanced degrees, by race and Hispanic origin, 1995-2002. (From the U.S. Census Bureau, 2003.) 35–39 25–29 –63.8% –81.0% 30–34 20–24 –68.0% –59.2% 15–19 10–14 Figure 1-14. Percent of the U.S. population 25 years and older with two levels of educational attainment, 1960-2000. (From the U.S. Census Bureau, 2003.) 5–9 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 70–74 1990 –6.6% –8.2% 1980 11.1% 10.9% 9.3% 65–69 1970 10% –8.3% 1960 16.2% 60–64 10.7% 15% 25.6% –10.9% –4.6% 7.7% 21.3% 17.0% 15.4% 13.2% 55–59 0% 20% –6.0% –3.9% 10% 52.3% 41.1% 27.2% 25.9% 24.0% 50–54 20% 25% –13.9% –4.0% 30% 30% 66.5% 50% White Black Hispanic 35% 84.1% 77.6% 70% 40% 40% High School Graduate or More College Graduate or More 45–49 80% 40–44 90% 10% –70% –80% –68.4% –67.4% –60% –80.0% –72.1% –50% –64.1% –60.9% –40% –48.7% –48.4% –30% –38.2% –40.1% –20% –31.2% –29.9% –10% –24.0% –24.2% 0% Figure 1-16. Percentage change in DMFT, by age and gender, 1971-1974 and 1999-2004. (From the NHANES I [1972-1974] and NHANES [1999-2004].) especially the elderly, primary caries does not usually create the most need for care; rather it is the sequelae of caries, and their management, that creates a large demand for tertiary care such as replacement of missing teeth with fixed and removal prostheses, oral surgery, and endodontic therapy. The DMF (decayed, missing, and filled) score is an imperfect measure of total caries experience.40-42 The DMF is a cumulative index; within an individual, it never declines. The average DMF never declines in a stable population. Average DMF can change only if individuals enter and leave the population, which is exactly what has been happening with the U.S. population and specific age groups within that population. As individuals with higher DMFs are replaced by individuals with lower DMFs, the average DMF can decline. Figure 1-16 displays the percentage change in DMF by age from 1971-1974 to 1999-2004.42-59 In general, the percentage improvements in DMF decrease with age. The bar chart shown in Figure 1-16 illustrates that the caries experience for younger age groups changed significantly, but the elderly have shown only slight improvement over the generation of elderly living 30 years ago. This is partially explained by the differential exposure to modern prevention, especially community water fluoridation, by different birth cohorts. Decreases of at least 24% were experienced by the younger birth cohort in each age group to the age of 50 years. A clear improvement advantage is noticeable among older women compared to men, but the seeming increase over time for 65- to 74-year-old women could well be a statistical artifact of small sample size. 12 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants Decayed Filled Missing Sound 28 14.2 14 10.0 9.2 6.9 8.7 11.2 8.1 8.1 11.4 6.9 14.8 5.5 17.4 3.4 20.7 4.8 6.9 0 2.1 1.7 1.3 18–24 25–34 35–44 6.4 1.2 45–54 5.5 1.0 55–64 4.5 0.7 65–74 3.2 0.7 75–79 Figure 1-17. Decayed, filled, missing, and sound teeth, by age, 1962. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, 1979; Thearmontree and Eklund, 1999; National Center for Health Statistics, 1997, 2004, and 2005.) Each component of the DMF index can be assessed separately. The “filled” component measures the number of filled teeth and is an indicator (albeit imperfect) of the utilization rate because existing restorations were placed by dentists. The “missing” component measures the number of teeth lost for any reason. It is a gross indicator of utilization because most missing teeth were extracted by dentists. However, the two components provide clues to different types of treatment provided. Filled teeth suggest treatment at an earlier stage of disease and possibly more expensive treatment if the restoration is gold. Alternatively, missing teeth suggest disease that had advanced to a more severe state, and either required extraction or an alternative treatment that was too expensive for the patient. The “decayed” component measures the amount of untreated caries. Untreated caries accumulates during periods between visits to dentists. A large number of untreated teeth are frequently associated with less regular utilization of dental services. The large declines in caries experience among younger birth cohorts portends well for a future reduction of need for care due to caries and its sequelae for future generations of elderly. It also indicates that loss of teeth can be expected to decline. Figures 1-17 through 1-20 show the various components of the DMF index from four national representative epidemiological surveys from 1962 to 1999-2004. In each figure, total edentulous individuals are excluded, so the figures indicate the DMF score for persons with some teeth remaining. Each bar in the four figures total to 28 teeth, the natural number of teeth in the permanent dentition, less the 4 third molars. Sound teeth count the residual between the number of DMF teeth and the total of 28. Although the age groupings are somewhat different between the four figures, it is apparent that a different pattern had emerged by the 1999-2004 time period. Inspection of the graphs in time sequence dramatically illustrates not only that the DMF index for the U.S. population has declined during the past 40 years, but also that the components of the index have shifted markedly. The largest shifts occurred in missing teeth and sound teeth. Data from the 1962 HES I survey demonstrate that tooth loss started at an early age and increased rapidly among older individuals (see Figure 1-17). Among those aged 18-24, individuals had already lost an average of four and a half teeth. Middle-aged adults had lost nearly one half of their permanent dentition. Among the elderly aged 65+, the dentition had been nearly wiped out. The converse was true for sound teeth. People 18-24 years of age had retained only one half of their dentition as sound teeth. Among the elderly, sound teeth numbered few, and this does not even count the edentulous, which accounted for 50% of the elderly. The next 40 years saw progressive and continuing improvement in caries experience. According to the 1971-1974 NHANES I survey, individuals aged 45-64 years had lost an average of 11.2 of their total complement of 28 teeth (see Figure 1-18). Among those ages 65-74 years, the average number of missing teeth was 15.2. By the period 1988-1992, among those aged 18-24 years, sound teeth averaged 21.8, and missing teeth had been almost eliminated. Even among those aged 50-64 years, almost one half of their teeth remained 13 Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants Decayed Filled Missing Sound Decayed Filled Missing Sound 28 28 5.8 7.7 13.1 14 17.1 11.3 4.9 15.2 13.0 21.8 14 5.3 2.4 0 8.3 8.1 1.7 0.9 0.6 18–44 45–64 65–74 6.4 Figure 1-18. Decayed, filled missing, and sound teeth, by age, 1971-1974. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, 1979; Thearmontree and Eklund, 1999; National Center for Health Statistics, 1997, 2004, and 2005.) 0 0.6 4.6 0.9 20–34 7.8 9.2 0.8 0.6 35–49 50–64 Figure 1-20. Decayed, filled, missing, and sound teeth, by age, 1999-2004. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, 1979; Thearmontree and Eklund, 1999; National Center for Health Statistics, 1997, 2004, and 2005.) sound, and missing teeth averaged 7 (see Figure 1-19). At the beginning of the 21st century (see Figure 1-20) all age groups showed an improvement, compared with just a decade earlier, in the number of missing teeth. sion through the gums to find the bone. This, in turn, means less pain and healing time for the patient. During the planning stages, the prosthetic tooth can be fabricated by a dental laboratory and can be ready at the time of surgery. This procedure bypasses the osseointegration period, in which the implant fuses to the bone. Although the implant still needs to heal, it can do so with the dental crown attached. Mini-implants are a relatively recent implant technology. They are used primarily for dentures; a series of mini-implants are placed through the mucosa into the bone of the jaw. Posts are used to anchor the appliance into place. Mini-implants mean less pain and healing time, and normally cost less than traditional dental implants. These cutting-edge dental implants also eliminate the wait on the healing process for the final step. Patients can start wearing their replacement teeth right away. Traditional dental implants meant that a new dental appliance was necessary, but some patients may be able to use existing dentures with mini-implants. Existing dentures can be fitted to attach to the posts implanted during surgery, enabling patients to return home with their repurposed dentures immediately after their surgery. Mini-implants are being used, in some indicated cases, to anchor dental crowns and dental bridges as well. Improvements in Dental Implant Technology Summary of Macro Factors New dental technology, materials, and designs have improved the dental implant procedure. Patients no longer have to wait to replace their missing teeth; the dental implant, abutment, and crown can be placed in just one visit.5-8 With immediate dental implants, the patient doesn’t need to live with a space between teeth or wear a temporary crown while waiting for the dental implant to heal. With single-visit dental implants becoming more successful, more patients are inquiring about this procedure. Using an ICAT cone beam CT scanner, a dentist can preplan dental implant surgery through 3-D imaging, creating a virtual mock-up of the mouth, which may eliminate an inci- We are slowly but progressively controlling dental caries in the United States and that, along with improved periodontal health, has contributed to a huge reduction in teeth lost to the two most common dental diseases. Thus, one may conclude that although the population is growing, has more discretionary buying power, and is better educated, tooth loss has dramatically declined. As those birth cohorts that lost large numbers of their permanent dentition early in life exit the population, they will be replaced by individuals who have lost fewer teeth. However, the same time period has shown that as younger cohorts mature to their elderly years, they will, on average, live to an older age, have more economic resources, Decayed Filled Missing Sound 28 14.5 10.9 19.9 14 3.5 7.3 1.0 6.1 0 9.3 9.2 0.9 0.7 0.7 20–34 35–49 50–64 Figure 1-19. Decayed, filled, missing, and sound teeth, by age, 1988-1994. (From the U.S. Department of Commerce, 1979; Thearmontree and Eklund, 1999; National Center for Health Statistics, 1997, 2004, and 2005.) 14 and be more ambulatory and in better general health than previous generations. Total edentulism is likely to plummet among future generations of elderly, so they will enter their later years with a largely intact dentition, and they will be more able and more likely to want to replace their fewer missing teeth than previous generations of the elderly. Science is constantly pushing the frontiers on knowledge and improving the outcomes of dental procedures. Implant technology has improved rapidly over the previous two decades and that improvement is expected to continue apace. These technical improvements will usher in better and less-expensive procedures for the replacement of teeth. It is likely that dental implantology will remain at the cutting edge of new opportunities. This will increase the attractiveness and complication of dental implants while improving their long-term survival and cost. Although changes in population, income, education, oral disease, tooth loss, and technology will be the ultimate determinants of the future need and demand for dental implants, two additional topics are important to anticipate what effect the improvement in tooth loss will have for dental implants specifically: individual factors that influence the choice between tooth replacement alternatives, and the time frame of the future projections. Individual Factors The decision that the patient and the dentist will make together depends on several factors that are particular to individual patient circumstances. Among these are: 1. The general health of the patient and any contraindications for the surgical implant procedure 2. The configuration of the remaining teeth in the arch as well as the opposing arch 3. The number of tooth spaces that need replacement by the dental prosthesis 4. The preferences of the patient and his/her willingness to undergo a more invasive surgical procedure required by the dental implant option 5. The relative cost of the implant option compared to the alternative; this alternative choice, of course, could be that the patient decides not to replace the missing teeth with any dental prosthesis In economics, a good or service is said to be a substitute for another good or service insofar as the two can be used in place of one another in at least some of their possible uses—for example, margarine and butter.60 The fact that one good can be substituted for another has immediate economic consequences as far as the options for tooth replacement are concerned. Frequently, patients and dentists have a choice between a tissue supported complete denture and an over-denture supported by or attached to implants. Likewise, an individual with one or two missing teeth, and with relatively healthy teeth for abutments on both sides of the space, has a choice between a tooth-­supported bridge or separate implants. All of the factors in the preceding list will affect the choice between an implant approach or an alternative. These Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants factors will vary between individuals. However, two of these factors have both individual and larger macro aspects. One factor is the technical trade-off between the alternatives and implants. As implants become more successful, more routine, and result in fewer complications, they may develop a further competitive advantage among the technical alternatives. In addition, as older individuals have more economic resources and remain healthier, they may increasingly opt for implants. Finally, the cost differential will play a critical role. Currently, over-dentures supported by or attached to implants are more expensive than tissue-supported dentures. Four recent articles assessed economic outcomes of the treatment alternatives.61-64 As expected, cost was an important determining factor in patient choice. Approximately 90% of patients felt that the cost of implant treatment was justified61 or that the cost-benefit ratio was positive.64 A short-term study in Switzerland compared economic aspects of single tooth replacement by implants with those of fixed partial dentures.62 This study found that implant patients required more office visits, but total time spent by the dentist was similar, and that the duration of the treatment was longer for the implant patients. However, the implant restoration demonstrated a superior cost-effectiveness ratio; the higher fixed partial denture laboratory fees outweighed the implant component costs. Of course, these comparative costs have changed and are likely to continue to change. The relative cost-benefit calculations that patients, in consultation with their dentists, make regarding dental implants will greatly influence the future market share of implants versus alternatives. Time Horizon For the next 20 years the current elderly and baby-boom generations will be dominant factors in the demand for adult dental services. The former and a large portion of the latter did not experience the full benefits of modern preventive dentistry. They lost more teeth as children and young adults than the birth cohorts that follow them. Also, their dentitions suffered from greater caries attack, but they received substantial restorative care. Some of these restorations are likely to fail with time and a portion of those will require extraction, either due to the sequelae of previous restorative treatment or due to the advance of periodontal disease. Both generations have retained most of their natural teeth and are likely to want to replace those teeth they have already lost or will lose. Individuals aged 50 years and older today are likely to experience a substantial need for tooth replacement, and many of them will act on that need by choosing to have dental implants. Over a longer time horizon, when today’s young adults and children reach the age at which previous generations required substantial prosthetic replacement, their tooth loss is likely to be much less than those previous generations. That is good news. They will retain teeth, many of them sound. Hopefully, these groups will enjoy natural dentition throughout their life and will navigate old age with functioning, healthy, natural teeth. Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants REFERENCES 1. Misch CE: Contemporary implant dentistry, St Louis, 2008, Elsevier. 2. Brown LJ: Adequacy of current and future dental workforce: theory and analysis, Chicago, 2005b, American Dental Association, Health Policy Resources Center. 3. Brown LJ: Adequacy of current and future dental workforce: theory and analysis, Chicago, 2005a, American Dental Association, Health Policy Resources Center. 4. Marcus DE, Drury TF, Brown LJ: Tooth retention and tooth loss in the permanent dentition of adults: United States, 1988-1991, J Dent Res 75(Spec Iss, Feb):684-695, 1996. 5. Brown LJ, Beazoglou TF, Heffley D: Estimated savings in dental expenditures from 1979 through 1989, Pub Health Reports 9(Mar-Apr):195203, 1994. 6. McCord JF, Grant AA, Watson R, et al: Missing teeth: a guide to treatment options, Edinburgh, 2003, Churchill Livingstone. 7. Esposito M, Murray-Curtis L, Grusovin MG, et al: Interventions for replacing missing teeth: different types of dental implants, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4(Oct 17):CD003815, 2007. 8. Davarpanah M, Martinez H, Kebir M, Tecucianu JF, Lazzara RC, et al: Clinical manual of implant dentistry, London, 2003, Quintessence. 9. Carr AB, McGivney GP, Brown DT: McCracken’s removable partial prosthodontics, ed 11, St Louis, 2005, Elsevier/Mosby. 10. Rosenstiel SF, Land MF, Fujimoto J: Contemporary fixed prosthodontics, ed 4, St Louis, 2006, Mosby. 11. Allen PF, McCarthy S: Complete dentures: from planning to problem Solving, New York, 2003, Quintessence. 12. Feine JS, Carlsson GE, editors: Implant overdentures: the standard of care for edentulous patients, New York, 2003, Quintessence. 13. Klemetti E: Is there a certain number of implants needed to retain an overdenture? J Oral Rehabil 35(Suppl 1):80-84, 2008. 14. Slagter KW, Raghoebar GM, Vissink A: Osteoporosis and edentulous jaws, Int J Prosthodont 21(1):19-26, 2008. 15. Branemark PI, Hansson BO, Adell R, et al: Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw. Experience from a 10-year period, Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 16(Suppl):1-132, 1977. 16. Tomasi C, Wennström JL, Berglundh T: Longevity of teeth and implants: a systematic review, J Oral Rehabil 35(Suppl 1):23-32, 2008. 17. Jung RE, Pjetursson BE, Glauser R, et al: A systematic review of the 5-year survival and complication rates of implant-supported single crowns, Clin Oral Implants Res 19(2):119-130, 2008. Epub Dec 7, 2007. 18. Iacono VJ, Cochran DL: State of the science on implant dentistry: a workshop developed using an evidence-based approach, Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 22(Suppl):7-10, 2007. Erratum in: Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants, 23(1):56. 19. Ong CT, Ivanovski S, Needleman IG, et al: Systematic review of implant outcomes in treated periodontitis subjects, J Clin Periodontol 35(5):438462, 2008. 20. Misch CE, Perel ML, Wang HL, et al: Implant success, survival, and failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus Conference, Implant Dent 17(1):5-15, 2008. 21. Salinas TJ, Eckert SE: In patients requiring single-tooth replacement, what are the outcomes of implant- as compared to tooth-supported restorations? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 22(Suppl):71-95, 2007. Review. Erratum in: Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 23(1):56. 22. Henry PJ, Liddelow GJ: Immediate loading of dental implants, Aust Dent J 53(Suppl 1):S69-S81, 2008. Review. 23. Sennerby L, Gottlow J: Clinical outcomes of immediate/early loading of dental implants. A literature review of recent controlled prospective clinical studies, Aust Dent J 53(Suppl 1):S82-S88, 2008. Review. 24. Ihde S, Kopp S, Gundlach K, Konstantinović VS: Effects of radiation therapy on craniofacial and dental implants: a review of the literature, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod Aug 26 2008. [Epub ahead of print]. 25. Kotsovilis S, Karoussis IK, Trianti M, Fourmousis I: Therapy of periimplantitis: a systematic review, J Clin Periodontol 35(7):621-629, 2008. Epub 2008 May 11. Review. 26. Klokkevold PR, Han TJ: How do smoking, diabetes, and periodontitis affect outcomes of implant treatment? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 22(Suppl):173-202, 2007. Review. Erratum in: Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants, 23(1):56. 27. Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Kakisis I, et al: Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Treatment of periimplantitis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2 (Apr 16):CD004970, 2008. 15 28. Linkow LI, Kohen PA: Benefits and risks of the endosteal blade implant (Harvard Conference, June 1978), J Oral Implantol 9:9-44, 1980. 29. Academy of Osseointegration: Committee for the Development of Dental Implant Guidelines, American Academy of Periodontology. In Iacono VJ, Cochran SE, Eckert MR, et al: Guidelines for the provision of dental implants, Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 23(3):471-473, 2008. No abstract available. 30. Fueki K, Kimoto K, Ogawa T, Garrett NR: Effect of implant-supported or retained dentures on masticatory performance: A systematic review, J Prosthet Dent 98(6):470-477, 2007. Review. 31. Oliver RC, Brown LJ: Periodontal diseases and tooth loss, Periodontology 2000 2:117-127, 1993. 32. Oliver RC, Brown LJ, Löe H: Periodontal treatment needs, Periodontology 2000 2:150-160, 1993. 33. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, International Programs Center. Available at: www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbprint.html. Accessed September 17, 2005. 34. U.S. Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2003, ed 123, Washington, DC, 2003, U.S. Government Printing Office; 2003:153 (No. 227). 35. U.S. Census Bureau: U.S. interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. Available at: www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/. Accessed September 18, 2004. 36. U.S. Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2001, ed 121, Washington, DC, 2001, U.S. Government Printing Office. 37. U.S. Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2004-2005, 2005. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/www/statistical-abstract04.html. Accessed Oct. 25, 2005. 38. U.S. Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2006-2007, 2007. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/www/statistical-abstract-04. html. Accessed Oct, 2008. 39. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. National economic accounts. Available at: www.bea.gov/bea/dn/home/gdp.htm. Accessed January 15, 2004. 40. Brown LJ, Wall TP, Lazar V: Trends in untreated caries in permanent teeth of children 6 to 18 years old, J Am Dent Assoc 130:1637-1644, 1999. 41. Brown LJ, Wall TP, Lazar V: Trends in caries among adults 18-45 years old, J Am Dent Assoc 133:827-834, 2002. 42. Kelly JE, Harvey CR. (1974). Decayed, missing, and filled teeth among youths 12-17 years: United States. 40 pp. (HRA) 75-1626. PB88228044. PC A03 MF A01. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/ pubs/pubd/series/sr11/100-1/100-1.htm. 43. Kelly JE, Harvey CR. (1979). May basic data on dental examination findings of persons 1-74 years: United States, 1971-1974. 40 pp. (PHS) 79-1662. PB91-223800. PC A03 MF A01. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/ nchs/products/pubs/pubd/series/sr11/100-1/100-1.htm. 44. Kelly JE, Van Kirk LE, Garst C. (1967). Total loss of teeth in adults: United States, 1960-1962. 29 pp. (PHS) 1000. PB-262958. PC A03 MF A01. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/series/ sr11/100-1/100-1.htm. 45. Brown LJ, Swango PA: Trends in caries experience in U.S. employed adults from 1971-74 to 1985: Cross-sectional comparisons, Adv Dent Res 7(1):52-60, 1993. 46. Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Surveys (various years). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 47. Douglass CW, Sheets CG: Patients’ expectations for oral health in the 21st century, J Am Dent Assoc 131(Suppl 1):35-75, 2000. 48. U.S. Department of Commerce. National Technical Information Service, Division of Health Examination Statistics: National Health Examination Survey (NHES I) 1959-1962. Hyattsville, MD, 1979a, National Technical Information Service. Dental Findings 1 Data Tape Catalog Number 1006. 49. U.S. Department of Commerce. National Technical Information Service, Division of Health Examination Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) 1971-1974. Hyattsville, MD, 1979b, National Technical Information Service; 1979. Dental Data Tape Catalog Number 4,235. 50. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Center for Health Statistics: Third National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 1988-1994, NHANES III Examination Data File (database on CD-ROM: Series 11, No. 1A, ASCII Version), Hyattsville, MD, 1997, National Center for Health Statistics. 16 51. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Surveys (various years before 2000), Hyattsville, MD, 1999, National Center for Health Statistics. 52. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General, Rockville, MD, 2000, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. 53. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2002). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2002 (machine readable data file and documentation). National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhcs. Accessed April, 2007. 54. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. (2004). National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Public-use data file and documentation. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes99_00.htm. Accessed June, 2004. 55. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. (2005). National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 2001-2002. Public-use data file and documentation. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes01_02.htm. Accessed March, 2005. 56. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2006). Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2005 (machine readable data file and documentation). National Center for Chapter 1 The Future Need and Demand for Dental Implants Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhcs. Accessed April, 2007. 57. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. (2007). National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 2003-2004. Public-use data file and documentation. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes03_04.htm. Accessed June, 2007. 58. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2002). Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2002 (machine readable data file and documentation). National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Maryland. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhcs. Accessed October 15, 2005. 59. Kelly JE, Van Kirk, LE, Garst CC. (1967b). Decayed, missing, and filled teeth in adults: United States, 1960-1962. 54 pp. PB-267323. PC A03 MF A01. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/series/ sr11/100-1/100-1.htm. 60. Stiglitz JE: Economics, ed 2, New York, 1993, W.W Norton & Company. 61. Pjetursson BE, Karoussis I, Burgin W, et al: Patients’ satisfaction following implant therapy. A 10-year prospective cohort study, Clin Oral Implants Res 16(2):185-193, 2005. 62. Bragger U, Krenander P, Lang NP: Economic aspects of single-tooth replacement, Clin Oral Implants Res 16(3):335-341, 2005. 63. Lobb WK, Zakariasen KL, McGrath PJ: Endodontic treatment outcomes: do patients perceive problems? J Am Dent Assoc 127(5):597-600, 1996. 64. Vermylen K, Collaert B, Linden U, et al: Patient satisfaction and quality of single-tooth restorations, Clin Oral Implants Res 14(1):119-124, 2003. Bob Salvin C H A P T E R 2 THE BUSINESS OF IMPLANT DENTISTRY Implant dentistry has evolved from a small part of a few clinical practices into a global business with thousands of clinicians placing and restoring implants manufactured by more than 100 implant companies. For many specialists and some general dentists implant dentistry has become the major part of their practice. Sophisticated software, coupled with the availability of in-office computed tomography (CT) scan machines, has transformed treatment planning for complex cases, whereas computer-aided design has significantly altered the production of precise custom abutments. The percentage of general practitioners who view the restoration of dental implants as an integral part of their everyday therapy continues to grow. Growth of the industry has attracted significant investment. Many of today’s implant manufacturing companies began as entrepreneurial start-ups, evolving during the past several decades into large-scale global businesses. These companies are using the latest technologies to create new implant designs, new surfaces, advanced aesthetic restorative options, and innovative new biological and grafting products. For clinicians, laboratories, dental implant manufacturers, and investors the global business outlook for implant dentistry is one of increasing opportunity. Factors leading to this conclusion include: • For centuries, people have sought viable alternatives for missing teeth, but in the last two decades dental implant dentistry has evolved into a vital part of mainstream practice. • Dental implants figure to grow dramatically as an attractive segment of the giant overall dental and medical market. • An aging population points to huge numbers of additional candidates for implants for at least the next several decades. • Increasingly, outside investments in dental implant companies will play a role in helping the segment expand to meet demand. • New financing methods are increasingly available for potential implant patients. • Consumer demand has increased for expanded dental implant insurance coverage. • The role of dental implant company field sales professionals will remain strong as they advise surgical and restorative practitioners and help direct them to training opportunities. • The ranks of professionals who are interested in learning to use implants are multiplying rapidly. This has been the impetus for creation and growth of a variety of educational opportunities. In addition, enhanced implant education, orientation, and instruction in the dental schools will play an important role in this growth. The economic future for implant dentistry represents solid opportunity for clinicians, dental labs, implant manufacturers, and patients because the entire scope of care focuses on improved products, practice methods, and patient outcomes. History Crude attempts at implantation go back centuries, at least to the Incas and Egyptians who implanted carved jade, sapphire, and ivory teeth. Nineteenth-century efforts included implantation of human teeth—a clumsy tooth transplant. The practice did not advance appreciably until the last quarter of the 20th century. As recently as 30-40 years ago, implant dentistry was performed by relatively few clinicians 17 18 Chapter 2 Global Dental Implant Market Dental Implant & Abutment Sales (US$ Billions) 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 Figure 2-1. Global dental implant and abutment sales growth from 2005 through 2040. and only in the most severe clinical cases. Training availability was limited and, by necessity, professionals in the United States studied extensively abroad. But in the last two decades, research along with aggressive marketing and sales techniques have validated the success of implants as a viable alternative for fixed and/or removable prosthetics. Growth Dental implants were just one segment of a $92.8 billion global dental services market for 2007.1 Global sales of dental implants and abutments rose more than 15% in 2006 alone, reaching $2 billion (Figure 2-1). The growth was strongest in Europe, where sales peaked at $750 million, which was 42% of the global market.2 Fueled by strengthened patient demand, interest in offering dental implant surgery increased among general practitioners. The market projects to continue double-digit annual growth though 2012.3 Volume for dental implants in the United States in 2008 was projected by Millennium Research Group to be 1.4 million procedures, for a treatment value of $2.3 billion. Projections show that by 2012 there will be 4.5 million implants and more than 2.8 million procedures annually in the United States.4 New Investment Dental implant companies, often started by entrepreneurs with limited outside capital, have increasingly caught the attention of venture capitalists and investment bankers, who view them as financially promising. Many medical and orthopedic company investors, attracted by the double-digit yearly growth The Business of Implant Dentistry of implant dentistry, have diversified their portfolios and in some cases shifted their focus to include dental implant companies. Dental implant firms strive to distinguish their brands with variations in implant and thread design, including implants for special situations such as enhanced aesthetics, lack of ample bone, and smaller diameter “transitional implants,” as well as developing new high-tech and biological coatings and surfaces. These companies fetch high gross sales/net profit selling price multiples because of their established brand names and share of market. Patient Demand The potential for the dental implant market in the United States is significant. Although studies show increased tooth retention among those aged 65 years and older, millions of Americans have lost some or all of their teeth. Tooth loss is most pronounced among the elderly, and data show the population in developed countries is aging and will continue to do so. In the United States, the baby-boomer generation is the major purchaser of elective plastic surgery and antiaging remedies. Boomers are the most affluent older generation ever in the United States and they will inherit the largest inflation-adjusted transfer of wealth in history: $10 trillion.5 Their propensity for discretionary spending has fueled remarkable growth in implant dentistry during the last decade. This boomer generation will swell the 65-year-plus population in the United States at annual rates of 1.5% to 3% from 2010 through 2035. Those older than 65 will increase from 12.4% of the population in 2000 to 20.6% in 2050 (Figure 2-2).6 Boomer-related implant growth can be counted on for at least another decade (Figure 2-3). Currently, implant market penetration in the United States is only 2%, according to Dr. Michael Sonick of Connecticut, writing for Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice in 2006. That translates to 3.5 implants per 1000 people.7 Worldwide, dental implant costs vary widely. As of 2008, implants in the United States averaged $1800 in addition to the cost of a crown, and the cost of full-mouth reconstructions with implants started at $12,000 per arch.8 In the United Kingdom the price of a single-tooth implant, including prosthetics, was generally $2,000. In Turkey, it was $800. A 2005 Millennium Research Group study showed that the U.S. market accounted for $370 million in dental implant sales, with an annual placement of 800,000. The average patient had two implants placed. Based on an average implant fee of $1500, the total 2005 dental practice revenue stream from placing implants was $1.2 billion, with an additional $1.2 billion in restorative revenue for a total of $2.4 billion. In 2007 the total number of implants placed in the United States was 1.7 million.9 Dental Implant Practice Growth As the trend toward mainstream status for dental implants continues, more general dentists will include implants as a core 19 The Business of Implant Dentistry U.S. Population Over Age 50 150 140 140 130 130 120 120 110 110 100 100 Figure 2-2. Population growth of U.S. residents over the age of 65 from 2005 through 2050. (From the United States Census Bureau.) offering, especially for single-tooth replacements. Increasingly, they will be prodded by patients who desire a wider range of services. A 2007 survey from The Wealthy Dentist showed that 53% of general dentists in the United States offered the restoration of implants to their patients.9a Many qualified their answer by adding that they accepted straightforward cases but referred their more difficult cases to specialists. The number of general practitioners in the United States surgically placing implants has not increased at a rate to match the expansion of the implant industry. Some dental schools have responded by adding implant treatment to predoctoral programs. Estimates place the numbers of dentists worldwide who offer dental implants at 140,000 out of approximately 940,000, or 15%. That percentage is projected to climb gradually, to as high as 40% by 2040.10 There is also a trend toward consolidation into large group practices in some parts of the country. This can bring a built-in referral base for an implant practice within a larger group. Benefits to patients can include longer hours of operation, a more accessible office, and a larger number of specialists within the same practice. Implant dentistry represents significant revenue opportunities, particularly on a dollar-per-hour basis. The use of sedation, intravenous and nonintravenous, presents a growing auxiliary income stream. 2050 2045 2005 10 2050 10 2045 20 2040 20 2035 30 2030 30 2025 40 2020 40 2015 50 2010 50 2040 60 2035 60 70 2030 70 80 2025 80 90 2020 90 2010 Population Millions 150 2005 Population Millions U.S. Population Over Age 65 2015 Chapter 2 Figure 2-3. Population growth of U.S. residents over the age of 50 from 2005 through 2050. (From the United States Census Bureau.) Costs and Overhead “One of the problems for the general practitioner,” says Dr. Charles Blair, a dental practice consultant in the Charlotte, NC area, “is that the crown/custom abutment and implant index for laboratory cost can be quite high.” 11 The patient cost of a complete single implant crown, including surgery, can easily be in the $3000 range. The clinical overhead cost for dental implants continues to rise as a percentage of the total cases. Included in overhead are the cost of the dental implant itself, the abutments and the other laboratory and prosthetic components, and, if required, membranes and bone grafting materials. This is in addition to the cost of general overhead, instruments, and disposables, such as anesthetic and sutures. Overhead also increases with the additional cost of implementing new technologies such as cone beam x-ray technologies and new growth factor biological products intended to promote faster healing. However, the additional costs of these new technologies lead to an improved quality of overall care as well as outcome. High-volume dental implant practices will gradually pay more attention to incremental overhead because the volume of materials they use is significant enough to affect their total overhead and profitability. They will increasingly take advantage of opportunities for volume discounts and buy-ins. Many 20 Chapter 2 clinicians have more than one implant system in their offices and, as implant systems become less differentiated, it is likely that implant companies will have to adjust their pricing to retain market share with their larger-volume customers. Because of variables in the total cost of implant treatment, including skill level, training, and practice overhead, a reduction in the cost of the dental implant itself is unlikely to make a significant difference in reducing the cost of patient treatment. Actually, as treatments become more complicated and require more site preparation, diagnostic CT scans, and other x-rays, the internal cost of treatment is more likely to rise than to fall. Dental Laboratories “In the early days of implant dentistry, case design as well as the costs of parts and pieces often were unpredictable,” says Scott Clark, vice president of Dental Arts Laboratories, Inc. in Peoria, IL. Profits on both the lab and doctor sides could be lost easily in destroyed components and misquoted cases, he says. To better serve the doctors sending complex implant restorative cases, many labs have established separate implant departments that are staffed by their most experienced technicians. New three-dimensional CT guidance technology enables the surgeon, restorative doctor, and laboratory to work in partnership in all phases of case planning and fabrication. Before surgery the laboratory can fabricate an extremely accurate surgical guide for implant placement and prefabricate the provisional prosthesis.12 New abutment technologies and CAD/CAM restorations, which have required labs to make both capital and learningcurve investments, have increased predictability and customization. Custom-milled titanium, gold-coated titanium, and zirconia abutments offer precise placement, improved coloring, and all-ceramic restorations for patient-pleasing aesthetic results. “These laboratory advancements save time, give more control over the end product and provide predictability in placement and restoration of implant prosthesis,” Clark summarized. “The overall result,” he added, “is that implant dentistry has become a significant sales and profit component for a successful dental lab.” General Practitioners and Referral Patterns As more and more general dentists integrate implant dentistry into their practices, and perhaps perform surgical placement in simple cases, the number of complex cases referred to experienced specialists will increase. In addition, with a continuing trend toward consolidation of some private dental practices into large group organizations, some of which have both specialists and general dentists, the sheer number of patients who are offered implants will dramatically increase. The Business of Implant Dentistry Study Clubs For specialists, the increasing technical and educational requirements for prosthetics have brought a change in referralbased practice development. To expand the therapeutic vision of the restorative dentist, some specialists who are placing implants have become the educational leaders in their communities. For them, providing excellent continuing education has become a competitive advantage in building relationships with their referring doctors and in building their implant practices. Often, a well-organized study club provides the opportunity for a better continuing education experience than that offered by the local dental societies. Many of these study clubs have evolved into comprehensive educational forums with excellent continuing diagnosis and treatment planning curricula. An excellent example is the Seattle Study Club organized by Dr. Michael Cohen, of Seattle, WA. It operates as a “university without walls” to educate doctors with methods that have proven more effective than the traditional lecture accompanied by a slide show. As of late 2008, the Seattle Study Club included approximately 220 study clubs around the globe, with a total membership of 6500. These clubs consist of specialists from a range of disciplines—restorative doctors as well as dental lab technicians. Cohen outlines three major principles of the Seattle Study Club: a strong emphasis on case management, participation with clinical interaction, and structured learning with and from peers. “Seattle Study Club members have access to an advisory board of skilled and experienced clinicians,” Cohen says. “They are a source for troubleshooting in more difficult clinical situations, pretreatment consultations on selected cases, one-to-one mentoring, and lectures to the group on basic and advanced treatment planning principles, current literature, and case reviews.”13 Insurance Coverage for Dental Implants Unlike medical insurance, dental insurance in the United States is designed as a specified maximum dollar benefit for the insured. This means that dental insurance carries a maximum payout for each procedure, usually combined with waiting periods and an annual ceiling for reimbursements. A stark statistical comparison illustrates the lack of progress on dental implant insurance coverage. In 1960, the average maximum benefit paid by dental insurance was $1000 a year; in 2003, the number was still $1000 annually. The typical insurance coverage of $1000-$2000 a year is not enough to cover the full cost of implant placement and restoration, particularly for large cases. Although dental insurance may or may not cover implants, it will in some cases pay for restoration of implants, but only up to the specific benefit of the policy. Because of relatively high costs for dental implant treatment compared to alternative therapy such as a tooth extraction, dental insurance usually Chapter 2 21 The Business of Implant Dentistry does not cover the full extent of treatment. This is particularly true of a full-mouth restoration. There is some movement in the insurance industry toward a larger reimbursement for implant dentistry. But with the total cost of health care and health insurance continuing to rise, many employers are opting to put limited resources into providing regular health care coverage. Additionally, many employers are engaging in increased cost-sharing with their employees on regular medical insurance, making it less likely that employees will want to or be able to pay extra for enhanced dental insurance benefits. Many dental policies classify an implant as a cosmetic procedure. Dental policies often include a clause covering the least expensive alternative treatment, and implants rarely qualify for coverage under this qualification. Policies that do cover implants usually feature a co-pay amount with a fairly steep threshold. Premiums for implant coverage typically are higher than standard premiums. Types and levels of implant reimbursement vary widely. Some dental plans cover surgical and restorative aspects of dental implants, up to an annual or lifetime maximum. Others cover surgical and restorative aspects in specific cases such as single-tooth implants in lieu of a three-unit bridge. Third Party Financing To make implants more affordable, many dentists are now offering third party consumer financing programs specifically developed for dentistry. These programs are similar to those currently used by plastic surgeons for elective surgery and ophthalmologists for LASIK procedures. Patients today are more willing to consider this financing. They tend to live longer and are more willing to make longerterm investments in their health care than their Depression-era parents or grandparents were. Major players in consumer financing for dental care include Care Credit, Dental Fee Plan, and Capital One Healthcare Finance. Factors Affecting Individual Practices Many specialists and general dentists, particularly those who have expanded their practices to include high-end implant dentistry, are significantly more entrepreneurial and businessfocused than the traditional physician medical market. With dental insurance playing a minimal role, dentists placing and restoring implants have been somewhat immune to the fee pressure and treatment fee limitations found in other areas of medicine. The result is that their incomes have risen while incomes for general practice physicians and for some specialty physicians have remained static or have declined. Unlike physicians who may do most of their procedures in hospitals or surgery facilities owned by others, dentists own their own “hospitals” where they “write their own checks.” Companies marketing in the implant dental field must reach more individual decision makers if they hope to close sales. This will require a shift in marketing thinking on the part of medical companies that invest in dental implant companies. Clinicians who desire to build the implant segment of their practices must adapt their communication skills to effectively convey the value of dental implant therapy to patients who will be paying for more expensive elective procedures out of their own pockets. Clinicians will need to concentrate on the value of implant procedures when compared to regular restorative dentistry. The message must show potential patients that dental implants promote long-term health, enhance cosmetic appearance, and offer improved function overall. Dr. Roger Levin, the founder of the Levin Group in Baltimore, MD, and a leading authority on implant practice management and marketing, believes these factors present a challenge. That challenge is to realize that the implant part of a dental practice operates on a different business model, or what he calls “a practice within a practice.” As an elective service, dental implants will rise and fall with the economy, he believes. “While they are one of the highest quality of life improvement services dentistry has to offer,” Levin says, “there are always other alternatives that patients can consider.”14 Levin believes implants will be a key growth factor for many specialty practices. “This will necessitate an entirely new approach to staffing and staff training,” he adds. “One that creates clear job descriptions and accountabilities for implant dentistry, including an expertly trained implant treatment coordinator.”14 A treatment coordinator can enable a dental implant practice to improve its communication skills. In large and more complex practices with an increasing revenue stream from implants a treatment coordinator can help manage patient appointment sequences and consult with referring doctors. “Practices that have an excellent understanding of implant scheduling, case presentation, case management, and follow-up will be well-positioned to reach their full potential,” Levin says.14 Sales Representatives The large dental supply distributors that dominate the U.S. market sell most commodity products used in a dental practice. However, dental implants have traditionally been sold as a specialty product by a dedicated direct sales force. Valueadded roles of the dental implant sales representative have been to help surgeons and their support teams learn how to use the implant system, to advise on treatment planning, and to support the restorative referral base. From the clinician’s perspective, a good deal of the differentiation between implant manufacturers will come in the form of tenured, professionally trained and responsive sales teams. Because of the consultative nature of the sale, there is often a significant loyalty factor and a relationship between the clinician and the professional sales representative. As products become less differentiated, professionalism and low salesperson turnover will likely be a significant part of the value added by the successful implant companies. As the larger “big box” dental supply houses add dental implants to their product lines, they will create a challenge for their sales representatives. These representatives may not be 22 Chapter 2 able to cover their regular route territories while also dedicating the time necessary to provide service and specialized technical support to the doctors placing implants. Internet The Internet is slowly emerging as a potential sales channel for dental implants. The dental implant companies maintain websites featuring new products and technologies, as well as the potential for distance learning opportunities. The best of these websites simplify the ordering process by showing customers which items they order most frequently. Several companies appear to be pursuing a strategy that bypasses the traditional outside sales force model by using the Internet as a stand-alone marketing vehicle. Without the overhead of a dedicated sales force, these firms typically emphasize price. Even with Internet sales, however, sales representatives perform a necessary service by aiding doctors in selection and placement of implants. They also can help educate doctors’ referral bases to better understand restorative options and help to guide potential patients through that process. It remains to be seen whether a total Internet marketing strategy without a sales force will be successful. Many manufacturers’ websites include information on the advantages of dental implants to the general public, and there is also a growing business segment of companies providing turnkey professional websites to clinicians. These sites, personalized for each doctor, provide an upscale look and feel with excellent illustrations, professional animations, and organized descriptions of available services. Training Thirty years ago implant training was available only to specialists. The Brånemark system, for example, required doctors to take specialized surgical training prior to purchasing that system. Effectively, they could not offer dental implant procedures until they completed the training. Today, universities and a number of private teaching centers offer training that includes a full range of implant placement information as well as grafting and site development. Fueled by a tremendous desire to learn from established experts in the field, continuing education has become a business for the best teachers in implant dentistry. Implant companies and suppliers of surgical instruments, bone grafting materials, and so on provide financial support for many of these courses. Some courses offer hands-on experience with demonstration models and observation of live surgery. In some instances, dentists bring their own patients to perform surgery under expert supervision. In addition, there appears to be high demand for cadaver courses that provide a hands-on experience to learn advanced procedures. In the United States, dental school graduates now number more than 4000 a year. More than 25% of general practitioners offer implants, and that number is projected to be 35% by 2012.15 Those figures are prompting dental schools to add implant placement and implant restorative programs to their The Business of Implant Dentistry curricula. Many endodontic programs also are including implant placement training. Grafting and Site Development Technological advances in bone grafting promise to reduce treatment time, which is likely to lead to further consideration and acceptance of implants among the general populace. Although new materials that promote faster bone growth may cost more, to the doctor and eventually to the patient, the tradeoff will be more satisfactory results. Today, optimal implant and tooth placement has become much easier and more predictable. Bone grafting and site development have revolutionized the placement of dental implants, which two decades ago was restricted to sites with available bone. Bone grafting procedure growth also includes socket grafts and periodontal defects. The increase in dental bone grafting procedures will parallel growth in implants as bone grafting is increasingly employed to prepare a site for implants. The Millennium Research Group projects bone grafts to number 1.5 million in 2008 and increase to 2.1 million by 2012.16 This growth will also apply to membranes that make bone grafting more predictable. These changes will lead to increased patient fees, additional dental practice revenue streams, and a need for additional training in treatment planning and in managing complications. Computer-Aided Implant Dentistry Advances in computer-aided implant dentistry continue to ease communication between the specialist and the restorative doctor. As increasing sales of office CAT scans attest, specialists are becoming more likely to install such machines, which make it easier and more attractive for referring doctors to send patients to them for complex cases. In addition, a few general dentists are beginning to acquire these machines and the technology that goes with them, though few, if any, general dentists will be able to maintain a practice based solely on implants. Solid surgical technique will continue to be a must, but new software will ease the treatment learning curve. This will help minimize mistakes and help general dentists decide which cases need to be referred to specialists. In an effort to offer a complete package, some implant companies are introducing their own treatment planning systems and software. This will mean a larger up-front investment for the individual doctor, but treatments and treatment planning will become quicker and more precise. “Technology is allowing us to reduce our chair time without sacrificing accuracy,” says Dr. Scott Ganz, D.M.D., author of An Illustrated Guide to Understanding Dental Implants, and a diplomate of the International Congress of Oral Implantologists. “The patient is going to benefit because he or she is going to be getting better products,” Ganz says. “Technology levels the playing field. It brings people from the lowest common denominator to the highest level of clinicians. It closes the gap tremendously.” He points out that laboratories and implant companies are delivering computer-milled metal or zirconia Chapter 2 23 The Business of Implant Dentistry implants that can be reproduced countless times with much greater accuracy than the human hand can achieve. “We’re increasing the accuracy,” Ganz says. “Technology allows us to do our job better. That’s what’s really critical.”17 Innovation “Implant dentistry is a prosthetic discipline with a surgical component,” says Dr. Burt Melton, a prosthodontist in Albuquerque, NM. Because implant dentistry typically begins with a prosthetic or restorative need, Melton says that growth in the number of implants placed is mainly the result of an increased number of general dentists who include implant dentistry in their therapeutic vision.18 Large-scale concentration on the dental implant market seems destined to usher the practice from niche status to a mass market. For years, most general dentists offered a three-unit bridge as the only treatment option for a missing single tooth. Now, many general dentists view that as an opportunity for a single-tooth implant, which is becoming widely recognized as the best treatment for replacing one tooth. Additionally, a growing number of root canal candidates are opting to have a tooth extracted and an implant placed. As patient aesthetic needs have come to dominate the location and placement of implants, implant companies have introduced innovative technologies to help dentists achieve a pleasing appearance in their finished work. Challenges That Need Innovative Solutions Innovative ideas and technologies must bring true value to a crowded marketplace. Companies that develop such innovations will differentiate themselves. Innovation will be a key factor in growth, product development, manufacturing, marketing, and overall strategy in implant dentistry. Manufacturers will set themselves apart by having stable, professionally trained sales teams and by effectively using continuing education to communicate the unique features and proper usage of their product lines. Both of these factors will become more important as treatment planning and diagnosis become more sophisticated through computer technology. Companies with outstanding systems will suffer if they do not have either the sales force or the teaching capabilities to make the clinical community aware of their products. Manufacturers will have to reduce operating expenses. Sales growth will help mitigate this need, but added efficiencies will be necessary. This can favor smaller companies that have lower general and administrative costs, place less emphasis on research and development, and take advantage of modeling and simulation technologies. Meanwhile, many established players may expand into biologics and prosthetics. Future innovations are likely in implant-biologics combinations. Leading manufacturers are working on projects such as a bone morphogenic proteins (BMP-2) (growth factor covered) implant, an implant combined with parathyroid hormone, and new implant insertion technology called bone welding.19 Additional trends to expect include: • Increased usage of new materials such as ceramics in abutment types and for individualized rather than standard solutions for better aesthetics • Redesigned implant surgery procedures aimed at reducing chair time and restoring tooth function as quickly as possible • Redesigned implant surfaces for faster and better osseointegration Projections and Predictions Statistics paint a sharply focused picture. By 2010, about 100 million Americans will be missing one or more teeth, in addition to 36 million who will be edentulous in one or both arches.20 The market for dental implants promises to grow dramatically as more patients opt for increasingly sophisticated solutions, for health and cosmetic reasons. Increasingly, patients who are implant candidates want fast procedures that are minimally invasive and offer long-lasting results. They demand an attractive appearance from the finished product. The range of solutions will continue to widen as the pressure for innovation is applied by increasing numbers of dental implant professionals and implant supply firms. Continued consolidation among dental implant manufacturers promises to entice larger outside investments. This should mean significant additional resources for developing state-of-the-art tools better suited to specific procedures and implant methods that yield more predictable results. In turn, it may help promote stronger individual practice development. Prompted by greater demand for postgraduate learning, educational opportunities for dental implant practitioners are growing from a variety of sources. These include expanding dental school curricula, the growing relevance of study clubs, as well as an increasing number of clinician, university, and manufacturer sponsored seminars. Many of those who work in the dental implant field have a focused vision for the profession that demographics are quickly ushering into reality. Just as clear are the numerous initiatives to meet the new demand realities that promise a prosperous future. This future will be based on increased growth, backed up by professionals with better education and training. They will have a better-developed appreciation for the depth of the dental implant market and the service they can perform. In turn, that will fuel the desire among the general populace to take advantage of implant benefits. The overall outlook is bullish for implant dentistry. Freeflowing innovations are coinciding with fast-growing interest in implants. This means nearly endless possibilities for patients, doctors and implant manufacturers. REFERENCES 1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group. 24 2. Tom Ehart for Kolorama Information, a division of MarketResearch.com, for PRLEAP.com, May 18, 2007. 3. Millennium Research Group: US Markets for Dental Implants, 2008. 4. Millennium Research Group: US Markets for Dental Implants, 2008. 5. Otwell, Thomas: Reported by Chana R. Schoenberger for Forbes, November 19, 2002. Also Louis F. Rose, DDS, MD, from multiple sources, 2000. 6. National Institute on Aging: US population aging 65 years and older: 1990 to 2050, www.nia.nih.gov/Researchinformation/ ConferencesAndMeetings/WorkshopReport/Figure4.htm, accessed September 3, 2009. 7. Sonick: Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice 10:16–17, 2006. 8. Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, New York, 2007, RDR Books. 9. Millennium Research Group: US Markets for Dental Implants, 2008. 9a. Half of General Dentists Placing Dental Implants: The wealthy dentist survey results, www.pr.com/press-release/40959, accessed September 3, 2009. Chapter 2 The Business of Implant Dentistry 10. Vontobel Research. Dental Implant & Prosthetics Market, 2008. 11. Interview with Dr. Charles Blair, Dental Practice Consultant, Belmont, NC. 12. Interview with Scott Clark, vice president, Dental Arts Lab, Peoria, IL. 13. Interview with Dr. Michael Cohen, periodontist, Seattle, WA. 14. Interview with Dr. Roger Levin, founder of The Levin Group, Baltimore, MD. 15. Petropoulos VC, Arbree NS, Tamow D, et al: Teaching Implant Dentistry in the Predoctoral Curriculum: A Report from the ADEA Implant Workshop’s Survey of Deans, J Dent Educ 70(5):580-588, 2006. 16. Millennium Research Group: US Markets for Dental Implants, 2008. 17. Interview with Dr. Scott Ganz, DMD. 18. Interview with Dr. Burt Melton, Prosthodontist, Albuquerque, NM. 19. Millennium Research Group. US Markets for Dental Implants, 2008. 20. Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, New York, 2007, RDR Books. Samuel M. Strong Stephanie S. Strong C H A P T E R 3 ESSENTIAL SYSTEMS FOR TEAM TRAINING IN THE DENTAL IMPLANT PRACTICE Once the clinician has sufficient mastery of the products and procedures required to successfully complete implant cases, the next challenge becomes training the dental team. This involves a two-tier approach in which clinical and patient informational skills must be learned and implemented. This chapter looks at the systems that must be incorporated by the entire staff in order to grow the implant practice. After the root-form implant was introduced into the United States in 19831 a generalized separation of duties specific to practice type developed. Initially, oral surgeons and then periodontists were the primary sources of surgically placed implants. In most cases, the restorative dentist referred implant candidates to these specialists, who sent them back to the restorative dentist for prosthetic completion after the surgical phase. Unfortunately, the initial lack of prosthetic training made completion of implant cases frustrating for surgical and restorative dentists, as well as for the patients. Although this trend has been significantly remedied with the increasing prevalence of implant prosthetic courses and literature, widespread confusion continues about how the surgical and prosthetic offices can best work together for the seamless completion of implant cases. In other practices, the prosthetic dentist does both surgical and restorative procedures. Whatever the mechanism for case completion, the office staff must become an integral part of implant education, procedures, and follow-up.2 Without the support of the entire team reinforcing the dentist’s recommendations, developing an implant practice can be very difficult if not impossible. Four Presurgical Phases Implant case development usually involves a joint effort between the restorative and surgical offices, facilitated by a protocol for interdisciplinary treatment planning. The following four phases are recommended for analyzing the prospective implant patient’s options for treatment and then delivering them to the patient.3 1. Diagnostic work-up 2. Laboratory procedures 3. Treatment planning conference 4. Case presentation These phases follow the initial exam to confirm that the patient has an existing condition that is treatable with dental implants. All dental team members must be cognizant of this pre­ surgical planning system. They must understand why it is important to properly plan the case and how to carry out these phases in a professional and organized manner.4 Diagnostic Work-up The patient who presents with a need for tooth extraction(s) or is already edentulous in any area qualifies as an implant candidate. This can be determined at an initial appointment with a visual exam and radiographs. The patient is then advised that a diagnostic work-up is needed to properly analyze the case and develop an appropriate treatment plan.5 25 26 Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice Figure 3-1. Telephone information slip. (Courtesy Pride Institute, San Francisco, CA.) From the first patient contact with the office by phone, email, or other means, each team member should have a working understanding of how the patient is to be guided through an educational process that will allow the patient to make an intelligent decision about treatment. The new patient calling to inquire about dental implants will be scheduled for a limited exam with x-rays, typically one or more periapical radiographs of a specific area and a panoramic radiograph. A preprinted form is used by the scheduler as a guide for gathering pertinent information (Figure 3-1). The appointment coordinator schedules this appointment and sends a health history and other pertinent administrative information to the patient to complete and bring to the appointment. The dentist then examines the area of concern and determines whether the case can be appropriately treated using implants. Additional diagnostic information is recommended, leading into the diagnostic work-up. Once the patient agrees to proceed, the work-up can be completed at the first appointment or scheduled for a later date. In addition to the necessary and appropriate radiographs, maxillary and mandibular diagnostic impressions are made using vinyl polysiloxane (VPS) impression material. VPS impression material is preferred over alginate impression material because it facilitates pouring of multiple stone casts. Fast setting (2 to 3 minutes) medium-viscosity VPS works very well to capture the detail needed for a diagnostic impression. If significant undercuts exist or if the dentition is periodontally mobile, extra-light-viscosity material is syringed into these areas with medium-viscosity material used in the impression tray. The extra-light material will usually pull out of the undercuts without danger of disrupting the teeth or existing restora- Figure 3-2. Diagnostic impression made from vinyl polysilo­ xane (VPS) impression material. tions (Figure 3-2). In severe cases of undercuts and/or mobility some form of block-out material should be placed. A bite registration is then made, either in the patient’s acquired maximum interdigitation or in centric relation. A series of photos are taken to document the patient’s existing condition (Figure 3-3). Additional digital photographic views may be helpful in thoroughly analyzing the case. The dentist or assistant may be aided by taking courses in dental photography or reading the existing literature on the techniques and equipment needed to acquire these images.6,7 A complete charting is made of the patient’s existing restorations, missing teeth, occlusal classification, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) status, and periodontal condition. The Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice 27 B A D C F E H G Figure 3-3. Photos taken to document a patient’s existing condition. A, Full face photo. B, Unretracted smile. C-E, Retracted views at 1:3 (C), 1:2 (D), and 1:1 (E). F, Retracted lateral view. Maxillary (G) and mandibular (H) occlusal views taken in a mirror. 28 Chapter 3 periodontal charting includes six sulcular measurements per tooth, plus notations of bleeding on probing, mobility, furcation involvement, plaque and calculus status, recession, and clinical attachment loss. The diagnostic work-up includes a facebow transfer for a semi-adjustable articulator, a centric bite registration, a full set of periapical and bite-wing radiographs, a panoramic radiograph, and a discussion with the patient regarding his or her long-term goals and desires from implant therapy. This discussion allows the clinician to form an idea of the patient’s attitude about dental treatment in general and implants in particular. Allowing the patient to review previous dental treatment will provide some insight as to how difficult or reasonable the patient may be if the clinician’s recommendations are accepted. It is recommended that a full diagnostic work-up should be completed for moderate to complex implant cases. For simple cases involving one to three implants, a limited work-up may suffice. In this case, diagnostic impressions, bite registration, and a more limited number of radiographs and photos should be taken. A panoramic radiograph is always taken due to the valuable information that can be gained by viewing all of the two-dimensional bone in the proposed area of implant placement. A properly trained clinical assistant can perform the facebow transfer procedure and take the photos that illustrate the patient’s preoperative condition. The ability to perform these procedures unsupervised adds to the value of the assistant as a team member by allowing the dentist to delegate these duties. If the patient is totally edentulous, notations are made of the ridge consistency (flabby, loose, or firm), arch form (square, tapering, ovoid), and vertical dimension (closed, open, or normal). The final part of the diagnostic work-up consists of a discussion with the patient regarding goals and expectations. Openended questions such as “What would you like to change about your existing smile and teeth?” tend to be the most helpful. In many cases, the patient wants a brighter smile, straighter teeth, closed spaces between teeth, or some other aesthetic improvement. Others may simply want the improved function that implants present by changing from a conventional denture to an over-denture or hybrid appliance. The patient’s responses to these types of questions can provide invaluable information. Because this is a rapport-building period, it is important for the clinician to listen. Let the patient talk as much as is possible to gain insight into exactly what he or she desires; there will be plenty of time later on to go into specifics about the details associated with treatment plan options. Active listening can be used here not only to display genuine interest and concern but also to verify that you understand what the patient is saying.8 Once the conversation about the patient’s desires and expectations is completed and documented, the patient makes an appointment to return for a case presentation. In the interim, the diagnostic impressions are poured in laboratory stone and mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator. It is a good idea to double pour the impressions to provide a duplicate set of diagnostic casts for the surgeon (if applicable) and/ Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice or laboratory technician. From the mounted casts the restorative dentist can determine the available inter-arch dimension for the final restoration as well as other pertinent information such as mesial-distal and buccal-lingual estimates for implant placement, existing occlusal relationship, arch form and length, and options for fixed or removable prosthesis fabrication. Laboratory Procedures In working up the treatment plan, the restorative dentist will produce diagnostic casts from the preliminary impressions and mount them on a semi-adjustable articulator. Subsequent working models will be mounted on this same articulator for consistency and comparison with the preoperative condition. From the facebow transfer, the maxillary model can be mounted on the upper member of the semi-adjustable articulator (Figure 3-4). The mandibular model is mounted on the lower member of the articulator using the centric bite registration. The semi-adjustable articulator and facebow transfer procedures facilitate the accuracy of all restorative procedures. In general, this is because the case can be mounted closer to the true arc of closure of the mandibular teeth relative to their interdigitation with the maxillary teeth.9 This principle of restorative dentistry, although always important, is particularly essential when opening the vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO). Having the models track on, or very near to, the arc of closure will reduce the occlusal adjustment needed upon delivery of these types of cases. In many instances, the VDO is opened in patients who have used partial or complete dentures for many years or who exhibit worn dentition. The mounted casts are reviewed along with the radiographs, photos, and chart notes including pertinent periodontal measurements. One of the valuable insights gained from the mounted casts is the determination of how much inter-arch space is available to the proposed implant restoration. In addition to the technical benefits of using a facebow transfer to mount models on a semi-adjustable articulator, Figure 3-4. Maxillary model mounted on the upper member of the semi-adjustable articulator and mandibular model mounted on the lower member of the articulator. Chapter 3 29 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice there is an additional benefit to the clinician. Many patients have not experienced this procedure in previous dental treatment, and they often equate the facebow procedure with a higher level of restorative dentistry. Many patients have remarked about the “sophistication” of the clinical procedures after having the facebow transfer completed. This perception can only increase the patient’s confidence in the clinician’s technical background and capabilities, an aspect of case acceptance and general rapport that cannot be overemphasized. Treatment Planning Conference All of the diagnostic data are duplicated and sent to the surgeon and/or the dental laboratory. At the treatment planning conference, the surgical dentist and restorative dentist meet or have a phone conference to plan the specifics of the case. A checklist of presurgical considerations is used to review all treatment options available for the implant case. A suggested presurgical checklist for consideration by the prosthetic and surgical team members includes these items: • Type of surgical template to be provided by the restorative dentist • Type of interim prosthesis to be provided by the restorative dentist • Numbers of implants for each treatment option • Anticipated lengths and diameters of implants • Ideal site for each implant • Need for grafting to place implants appropriately • Fixed or removable prosthetic options • Screw or cement retention for fixed cases • Splint screw or cement retained restorations for fixed case versus single crowns • Bar or attachment-retained format for removable cases • Immediate or delayed loading sequence • Anticipated surgical and prosthetic treatment time estimate The presurgical checklist is used to guide case analysis whether a surgical dentist is involved in the case or both surgical and prosthetic procedures are being performed inhouse. When the case involves an interdisciplinary effort with the surgical dentist, duplicate mounted diagnostic casts, radiographs (FMX and/or panoramic), pertinent chartings, and patient-specific notations are sent to the surgical office. A form is useful to deliver a brief description of the purpose for the evaluation (Figure 3-5). The restorative dentist may need to discuss any specific issues or concerns about the case with the surgeon prior to the surgical evaluation appointment. Under this scenario, the two principal clinicians (surgical and restorative) either meet face to face or arrange a scheduled phone conversation to complete the treatment planning conference. A restorative staff member is responsible for sending the diagnostic materials in the preceding list to the surgical office for this meeting as well as follow-up chart documentation after the conference. The treatment planning conference must occur shortly after the diagnostic work-up to expedite the formulation of appro- Surgical Evaluation Form Patient name: Ms. Jane Doe Referred by: Dr. Sam Strong Implant area: Entire maxillary arch Enclosed: FMX ; Panoramic Models ; Photos Treatment planning conference Figure 3-5. Example of a surgical evaluation form. priate treatment options. Ideally, this phase should be completed within a few days to facilitate scheduling the case presentation within 2 weeks of the diagnostic work-up. If the restorative clinician intends to perform all the surgical and prosthetic implant procedures, a designated staff member assembles these diagnostic materials for timely evaluation. The surgical evaluation consists of confirming all data sent from the restorative office, reviewing the patient’s health and dental history, and confirming the recommendations of the restorative dentist. Bone grafting options (if needed) should be reviewed. The patient is advised about whether the grafting can be accomplished simultaneously with extractions and/or implant placement. If these procedures are to be done separately, an estimated timeline for their completion and referral back to the restorative dentist for definitive prosthetic procedures is given to the patient. A written financial estimate is also produced for the patient. Informed consent may be procured at this appointment or delayed until prior to initiating the surgical procedures. Case Presentation All team members will be involved with making sure that the presurgical phases are completed efficiently and professionally. A smooth operating progression through these phases makes case acceptance more likely. Following the treatment planning conference, the surgical and restorative dentists can deliver the case presentation to the patient. This can be done jointly, but the more practical method is for the clinicians to deliver this presentation separately to the patient in their own offices. At this appointment the patient receives a detailed discussion of all treatment options, treatment length, and fee estimates. The front office and clinical assistants are primarily involved in preparations for this event. The patient should be scheduled for a specified time when the clinician can give undivided attention to the presentation. The front office member schedules this appointment and stresses the importance of the patient’s spouse or other decision maker’s attendance. This is key for case acceptance and is more successful than having the patient return home to “translate” what the dentist said. 30 Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice PATIENT TREATMENT PLAN 08/14/08 Samuel M. Strong, D.D.S. 2460-0 For: John Doe Service description Prv Tooth Fee Surgical stent SMS MAX Diagnostic photographs SMS Provisional crown SMS 12 Implant crn-porc/noble SMS 12 UL1st bicus Thermoplastic splint SMS Insurance Patient Treatment phase Total: 2470.00 2470.00 This treatment estimate is valid for 60 days Implant-supported crown of porcelain fused to noble metal: Fee includes implant transfer assembly, implant analog, titanium machined or custom cast abutment, custom cast precious metal framework, custom fired porcelain, and retaining screw. Comments: Figure 3-6. Example of a patient treatment plan. In preparation for this appointment, the dentist outlines the surgical and/or prosthetic treatment plan to a front office member. The specific line items of all procedures are entered into the office computer with subtotals for each arch (Figure 3-6). A timeline for the necessary appointments is developed for guidance in scheduling all appointments should the patient decide to proceed with treatment (Figure 3-7). The front office compiles these documents into a folder to give to the patient at the case presentation appointment. Other pertinent material such as practice brochures, implant product brochures, and financing options is also placed into the folder for the patient. A clinical assistant is responsible for placing the diagnostic casts mounted on the semi-adjustable articulator in the consultation room. These models have been trimmed and the articulator cleaned to show that meticulous attention to detail is being applied to the patient’s case. Any visual aid models that illustrate the patient’s treatment options also are placed into the consultation room. Photos of the patient’s existing condition are viewed on the computer monitor along with the patient’s radiographs. Some dentists find it best to schedule all case presentation appointments together on certain days to avoid interrupting “productive” days of procedures. Others feel that one or more case presentations can be effectively placed into the daily schedule without diminishing the productivity of the day. At Appointment 1 Transfer impression 1 hour 3 weeks Appointment 2 Framework try-in, deliver provisional bridge 2 hours 1 week Appointment 3 Adjust provisional bridge 30 minutes 2 weeks Appointment 4 Deliver implant bridge 1 hour Figure 3-7. Example of an appointment timeline developed as a guide for future scheduling. the morning huddle (to be reviewed in detail later) case presentation appointments are noted to make the dentist and staff conscious of how they will fit into the day’s schedule. The front office personnel should be responsible for having the consultation room clean and presentable when the patient Chapter 3 31 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice arrives. The patient and spouse are ushered directly to the consultation room upon their arrival, and the dentist and all staff members are alerted to their presence. The case presentation is the culmination of all the work from the initial exam through the diagnostic work-up and treatment planning conference, and this appointment is crucial in determining whether the patient accepts the treatment recommendations. Thorough preparation and execution of the presentation should reflect the attention to detail necessary to complete the case successfully. A disorganized or poorly conducted presentation can result in a lack of confidence from the patient. A suggested agenda for the case presentation is: • Review patient’s goals and desires • Review existing conditions • Present treatment options (implant and nonimplant) • Answer any remaining clinical questions • Present financial estimate and options for payment The dentist discusses all of these agenda items with the patient and patient’s spouse (or other interested party). The patient’s radiographs and diagnostic models are used to illustrate points about his or her existing condition and treatment options.10 Demonstration models, brochures, flip charts, videos, photos of similar cases, patient testimonials, and any other visual aids are used to support the dentist’s recommendations. The front office team member who worked with the dentist on the treatment plan also should attend the entire case presentation. By hearing the dentist’s delivery of treatment options and the patient’s responses, this person gains a valuable perception of the patient’s attitude toward treatment. After the clinical presentation is completed, the front office member delivers the financial payment options to the patient. The dentist must develop a clear set of financial guidelines for the front office member to follow in presenting payment options.11 This staff member functions as a financial coordi­ nator and/or appointment coordinator. The patient may be offered third-party financing with various payment plans. The financial coordinator should be thoroughly familiar with these plans and be able to identify the monthly payments resulting from 12-, 24-, or 36-month plan options. Most of these plans also offer interest-free options. The financial coordinator must be able to identify the patient’s monthly financial responsibilities for each option quickly to enable the patient to make an informed decision. The following checklist is useful in presenting financial options to the patient: • Brief review of treatment options and appointments needed • Present the fee for recommended treatment • “How will you be taking care of this?” • Offer 5% courtesy adjustment if entire fee is paid in advance by check or cash • Collect at least 20% down payment to reserve the appointment times • Offer third-party financing if needed • Secure a signed financial agreement stating how the patient will pay for services • Informed consent signed by patient and witnessed by staff member • Schedule all appointments needed to complete the case An entry in the patient’s chart should document all items reviewed in the case presentation, noting that all risks, benefits, and alternatives have been reviewed with the patient. In addition to this documentation, a consent for treatment form must be secured when the patient agrees to proceed with treatment. The need for informed consent applies to both surgical and prosthetic procedures (Figure 3-8). The following information from the dentist’s treatment plan timeline is used to schedule these appointments: • Type of appointment (surgical example: extractions and bone grafting; prosthetic example: implant level impressions) • Length of time anticipated to complete the appointment. Specify assistant and doctor units • Time intervals between appointments • Charges to be made at each appointment • Payments to be made at each appointment (when applicable) This information can be placed in the folder given to the patient. It may be helpful to enter the appointments and associated information into a calendar that is then given to the patient. This also serves as an internal marketing tool for the practice. The appointment coordinator schedules the initial appointment for surgical template impressions unless the diagnostic casts can also serve this purpose. The first surgical appointment is scheduled with sufficient time to produce the template (Figure 3-9). If extractions and/or significant bone grafting are required, the template fabrication may be delayed until implants are ready to be placed. The front office and clinical assistants must coordinate their responsibilities to make sure the template cast is sent to and returned from the dental lab in time for the surgical procedure. In addition, a provisional appliance such as an interim removable partial denture or full denture may require fabrication for delivery at a surgical appointment. Clinical Assistant Responsibilities The clinical assistant for surgical procedures is responsible for preparing the operatory and the patient for implant surgery.12 If a sterile surgical field is utilized, one assistant serves as the “sterile” assistant while another may serve as a “rotating” assistant. A thorough understanding of all surgical instruments and associated material is necessary in addition to confirming that sufficient inventory of implants is on hand. For prosthetics, the clinical assistants should understand the following implant components and their applications: 1. Healing abutment: This component screws into the implant and maintains a channel through the gingival tissues to the top of the implant (Figure 3-10, A). 2. Impression coping: This component transfers the position of the implant through an impression to the working master cast (Figure 3-10, B). 32 Chapter 3 3. Implant replica (analog): This component is an exact replica of the coronal portion of the final implant (Figure 3-10, C). 4. Abutment: This is the component to which the final restoration is either cemented or screw retained (Figure 3-10, D). Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice The clinical assistant is also responsible for a sufficient supply of all components and prosthetic tool kits for the upcoming restorative implant cases. A “value-added assistant” can perform duties beyond those of the traditional assistant. For example, a properly trained clinical assistant as part of an expanded auxiliary function can ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF RECEIPT OF INFORMATION A ND CONSENT BY PATIENT FOR PROSTHETIC TREATMENT Patient’s Name: ____________________________________________________ State law requires that you be given certain information and that we obtain your consent prior to beginning any treatment. What you are being asked to sign is a confirmation that we have discussed the nature and purpose of the treatment, the known risks associated with the treatment, and the feasible treatment alternatives; that you have been given the opportunity to ask questions; that all your questions have been answered in a satisfactory manner; and that all the spaces in these forms were filled in prior to your signing it. 1. I hereby authorize and request the performance of dental services and prosthodontic procedures for the above named patient from Dr.(s)____________________________________, or staff and further authorize the performance of whatever procedure(s) in the judgment of the above named doctor may deem necessary. I also authorize the administration of such anesthetics or analgesics that the doctor may deem advisable. I further authorize any oral surgical procedure(s) that may be necessary during my treatment. I further consent to the taking of photographs, films or other materials showing the condition of my mouth or my treatments for the purpose of documentation, my education, or the showing to the public at large or other display of such photographs, films or other materials including dental records, x-rays if necessary for dental, scientific and educational purposes. (All rights to remuneration, royalty or other compensation to the patient, his heirs or assigns or myself are hereby waived.) A credit check may be obtained to help establish a credit history. Further, if I fail to pay my balance in full for treatment rendered, I will be liable for any additional legal fees, collection costs and interest incurred in collecting the balance due. 2. I authorize the fabrication of the prosthesis that has been prescribed by the following Dr.(s) ______________ that has been indicated by the diagnostic studies and/or evaluations already performed to utilize with my implant(s) and treat any other dental needs. 3. Alternatives to the implant prosthesis(es) have been explained to me, including their risks. I have tried or considered these alternative treatment methods and their risks, as listed on the “Request for Prosthetic Treatment” page, but I desire the implant prosthesis(es) used to help secure and/or replace my missing teeth which is also listed on that same page. 4. I am aware that the practice of dentistry and dental surgery is not an exact science and I acknowledge that no guarantees have been made to me concerning the success of my implant prosthesis(es) and the associated treatment and pr ocedures. I am a ware that the implant prosthesis(es) may fail, which may require further corrective actions and possible removal of said prosthesis(es). 5. As with any dental prosthesis(es), there are possible complications of which I have been made aware. These complications include but are not limited to the following: risk of improper fitting bridge work; risk of improper occlusion; disease develops due to improper home care or other reasons; loss of permanent teeth; loss of the prosthesis(es) and/or implant(s) if systemic disease develops, and wear or breakage of the implant component parts and/or prosthesis(es), and risk to the chewing surface material(s). This material(s) has tooth like hardness. However, just as with natural teeth, they run the risk of fracture or breakage. If damage to the material(s) occurs it may need to be repaired. The amount of damage to the prosthesis(es) will determine whether or not it may be repaired or remade. The cost to repair will vary ICOI members receive these forms gratis. For information on the world’s largest implant society, call 888-449-ICOI, fax: 973-783-1175, e-mail: icoi@dentalimplants.com or visit www.icoi.org Rev. 3/08 Figure 3-8. International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) patient consent form for prosthetic treatment. (Copyright the International Congress of Oral Implantologists, Upper Montclair, NJ. Reprinted with permission.) Chapter 3 33 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice depending on the extent of the damage. If a chip occurs it may only need to be polished. If the fracture is larger it may need resurfacing and may only last four to six months. Should the damage be excessive, it may require that the crown or the entire bridge be remade. There will be a fee to repair and/or replace the crown or bridge. 6. I have been advised that use of tobacco, alcohol and/or sugar may affect the implant(s) and the prosthesis(es), which may limit the success of this treatment. Gum disease is the leading cause of tooth loss today. The teeth or implant(s) which support your prosthesis(es) can develop gum disease, if proper care is NOT given to them. Professional preventive maintenance visits and professional cleanings are mandatory every three to six months. Home care, brushing and flossing should be performed three times daily. Our hygienist will recommend a daily program for your specific needs. 7. Avoid eating or chewing sticky foods such as taffy and excessively hard objects or foods like hard candies, some nuts, ice, etc. This may loosen or damage the prosthesis(es). Fixed teeth rarely come loose. However, if this occurs it will put excessive force on the remaining implant(s)/teeth. Natural teeth may decay under loose restorations. This too may result in loss of the teeth or implants. Therefore, if the prosthesis(es) should become loose, or if any changes to the bite occur, please notify the office immediately. 8. I certify that I have read, have had explained to me, and fully understand this foregoing consent to implant prosthetic treatment and that it is my intention to have the foregoing treatment carried out as stated. I have been advised that this is a relatively new procedure and that the information concerning the longevity of the particular implant(s) and the prosthesis(es) to be used may be limited. However, I have discussed this, as well as the nature of the implant product to be used, and I consent to the procedure knowing its risks and limitations. IN SUMMARY 9. I understand that sometime after insertion the implant(s) will be uncovered and/or implant head(s) will be placed into the implant(s). The restoring dentist will restore the implant(s) using routine dental procedures and make a prosthesis(es) that will be attached to the implant(s). The problems with having or wearing this prosthesis(es) have been explained to me. I may lose the implant(s) once it has been placed or the prosthesis(es) may fracture, wear or parts may break and need to be replaced at my cost. In addition, it has been explained to me that the prosthesis(es) will either be cemented or placed in position by screws. These screws can come loose and/or break and may need to be replaced at any time. There will be a charge to remedy these situations. It has been further explained to me the need for meticulous home care. The tissue around the implant(s) may become irritated. I may need additional surgery to insure the health of the implant(s). Possible oral hygiene regimens have been explained to me and I have been told what type of dental care devices I may need. Preventive maintenance procedures have been explained to me and I know that I should come back to visit the dentist who has placed the restorations at least three times a year. As with all other dental procedures, no guarantee can be given as to the longevity of this procedure. It should be noted that I have read this, clearly understand this, and I have had all this information explained to me. I have had all my questions answered by the dentist and have no remaining substantive questions relative to this information or my treatment. 10. Finally, all spaces were filled in prior to my signature and I understand that I am free to withdraw my consent to treatment at any time. _____________________________________________________________________ Signature of Patient or Guardian ______________________________ Date _____________________________________________________________________ Signature of W itness ______________________________ Date Figure 3-8, cont’d. Continued 34 Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice REQUEST FOR IMPLANT PROSTHETIC TREATMENT I request that dental treatment be provided for me based on the following information: 1. I have requested treatment because: __________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. I understand that my dental needs can be treated by the following other methods: Upper:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Lower: ______________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. I understand that my selected prosthesis(es) will consist of the following: Upper:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ Lower: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 4. I understand that the treatment I have selected, has the following advantages over the alternative methods of treatment: Upper:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ Lower: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 5. The expected outcome of treatment (prognosis) is: Upper:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ Lower: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 6. If I elect not to have treatment, I understand the following may occur: Upper:_____________________________________________________________________________________________ Lower: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 7. I understand that the treatment selected, like all treatment, has some risks. The significant risks involved in my treatment have been explained to me and are listed below. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 8. I have been allowed the time and opportunity to discuss the proposed treatment and alternatives and the risks noted above with the doctor. I understand to my satisfaction the proposed treatment and its risks and have no substantial questions regarding this information. _____________________________________________________________________ Signature of Patient or Guardian ______________________________ Date _____________________________________________________________________ Signature of Witness ______________________________ Time ICOI members receive these forms gratis. For information on the world’s largest implant society, call 888-449-ICOI, fax: 973-783-1175, e-mail: icoi@dentalimplants.com or visit www.icoi.org Rev. 3/08 Figure 3-8, cont’d. perform the facebow transfer used in the diagnostic work-up. Photos of the preoperative, in-progress, and case completion segments also can be procured by this assistant. Proficiency in these and other areas of delegated duties makes the team member more valuable to the office and can result in higher financial compensation as well as professional growth. Coordination between the clinical assistant and front office is needed to ensure that labwork for implant restorations is completed and returned to the office prior to the patient’s appointments. Surgical templates, interim partial dentures, interim full dentures, or interim crowns and fixed bridges may be required on the date of extractions, bone grafting, and/or Chapter 3 35 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice Figure 3-9. The surgical template. implant placement. The clinical assistant is responsible for having these prostheses completed or returned from the dental laboratory in time for the patient’s surgical appointment. To keep track of this information in the office, a system must be developed so that the appropriate team members know which components and restorations are in-office and which ones need to be sent to a surgical office in a timely manner. This information can be tracked by computer (using software such as Lab Track, Dentech, Detroit, MI) or with a manual system. Both methods can minimize the prospects of not being completely prepared for the successful completion of implant procedures. The computer software alerts the staff of all lab cases that have been sent out to commercial dental labs, along with the anticipated return date to the office. This information is in addition to a manual tickler file system that can be customized to an office’s specifications. Each implant case is logged onto a tickler file card with information about the current status (Figure 3-11, A). A front office staff member is responsible for filling out the card as the case progresses. The implant type, diameter and length, date of placement, and anticipated timeframe for beginning the final restoration are entered. This information is then transferred to a working “Implant Case Calendar” (Figure 3-11, B), which can be kept in the area where the morning huddle is held prior to starting patient care each day. The Morning Huddle All team members attend the daily morning huddle before patient care begins.13 Responsibility for running this meeting is rotated monthly among the three office departments (front office, clinical assistants, and hygiene). A written agenda is followed so that the huddle can be completed in about 15 minutes. Line item topics covered in the huddle include lab cases due into the office or to be shipped that day, the previous day’s production and collection figures, anticipated production for that day, identification of the “Patient of the Day,” special considerations for any patients, confirmation of financial agreements made, and reminders to dispense office marketing materials. An additional line item in the huddle agenda is identification of all implant cases for that month that require some action on the part of team members. This information is viewed by looking at the Implant Case Calendar (see Figure 3-11, B). Components and lab work to be ordered are highlighted in yellow. Once these items are either completed and in the office or sent to a surgical office, pink highlighting can be added over the yellow, which results in an orange highlight. The same color-coded system can be used in charts to identify pending or completed treatment.14 This color-coding system helps the office staff easily identify cases still needing attention and the date required for completion (yellow) and those that have all preoperative preparations completed (orange). Coordinating the computerized tracking of lab cases, the manual tickler file, and the morning huddle increases the efficient management of implant cases. It becomes less likely that a critical implant component or prosthesis will not be available when needed. Failure to attend to these details can result in severe embarrassment to the office. Implant patients have committed significant expense and time by agreeing to proceed with recommended treatment and they expect a level of professionalism, organization, and expertise beyond the norm. Training office personnel to carry out a system as described in the preceding paragraphs can make the difference between fulfilling the patient’s expectations or failing in this regard. Storage of implant cases post completion is also recommended. This typically becomes the responsibility of a clinical assistant who boxes pertinent models and other case materials for future reference and documentation. A manual or computerized list can identify the case box by patient name or number. The dentist should identify which case items should be stored and which can be discarded to minimize the demand for storage space. Hygiene Department The subject of hygiene maintenance for the implant patient is covered in Chapter 30. This chapter briefly reviews the key role played by the dental hygienist in an implant-oriented restorative practice. The hygienist should have ready access to implant brochures, visual aids, and video information specific to implant cases. Hygienists play a particularly important role by virtue of their training and ability to identify implant options to the patient. It is a good idea to have some sort of patient information video playing continuously in the hygiene operatory (for example, the CAESY DVD, CAESY Education Systems, Vancouver, WA). Audio is not used with the video unless a specific application of implants is to be demonstrated. More detailed patient education can be obtained by using a specific implantoriented DVD that reveals treatment options for any existing condition in a viewing period of about 10 minutes (for example, Implant Options and Alternatives, Strong Enterprises, Little Rock, AR). This can be viewed while the hygienist is treating the patient or at the appointment conclusion. 36 Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice A B C D E F G Figure 3-10. Implant components. A, Healing abutment. B and C, Impression coping. D and E, Implant replicas. F and G, Abutment. Chapter 3 37 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice A A B B Figure 3-11. A, Tickler file card with information about the current status of a specific implant case. B, Implant case calendar. Many dental hygienists are not familiar with full-arch removable prostheses.15 However, the implant-oriented practice often becomes proficient with full-arch removable implant over-dentures, creating a new area of training for the hygiene department. This type of implant prosthesis snaps onto either a bar that is fixed into the implants or directly onto implant abutments16-18 (Figure 3-12). The hygienist should be familiar with all aspects of over-denture evaluation and maintenance as well as the common attachments used by the office for overdenture retention. Attachments can be replaced by a trained auxiliary such as the hygienist at regularly scheduled maintenance appointments. Continuing care appointments are recommended for patients with removable implant prostheses at 3- to 4-month intervals, the same schedule recommended for fixed implant cases. The removable implant over-denture is first evaluated for the condition of the acrylic base and denture teeth. The retaining implant bar and/or attachments are then checked for looseness or need of replacement. Any obvious denture base C Figure 3-12. Examples of full arch removable implant overdentures. A, An implant prosthesis that snaps onto a bar that is bolted into the implants. B and C, An implant prosthesis that snaps directly onto implant abutments. fracture or deterioration is brought to the attention of the patient and dentist immediately, without proceeding further with the appointment. An intact over-denture is placed into a sterile beaker with full-strength Type IV ultrasonic cleaner for 10 to 20 minutes (Figure 3-13). The hygienist can then debride hard and/or soft accretions from the implant connecting bar or attachments using plastic, graphite, or titanium instruments. The over-denture is then manually cleaned with a new toothbrush and chlorhexidine scrub soap followed by an herbal powder application to disinfect the denture and remove the chemical taste left by ultrasonic solutions. 38 Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice components such as impression copings can be provided by the IC for implant impressions. Most important, the IC can maintain the lines of communication between the restorative and surgical dentists and their team members. Attention to this area will reinforce the patient’s favorable opinion of both offices and can encourage the restorative dentist to refer future cases to the surgical office. Key Concepts for the Implant Team Member Figure 3-13. Intact over-denture in a sterile beaker with fullstrength Type IV ultrasonic cleaner. A denture adjustment kit should be kept in the hygiene operatory for use by the dentist when adjusting denture base sore spots and occlusions, and for polishing the denture base and teeth. The ability to effectively advocate the advantages of implant therapy, perform expanded maintenance of implant restorations and prostheses, evaluate and troubleshoot implant restoration problems, change over-denture attachments, and recommend products for home care can significantly increase the hygienist’s level of expertise. In turn, this team member becomes a value-added hygienist, further enhancing his or her role and compensation in the office. The Implant Coordinator Many surgical implant offices have an established implant coordinator (IC) as part of the staff. This part-time or full-time position can serve as in intra- and inter-office liaison to improve the efficiency of completing implant cases and as a marketing coordinator to the referring clientele. When employed by a surgical office, the implant coordinator should maintain contact with the referring restorative office from initiation to completion of implant cases. A well-trained IC can provide in-office training for referring dentists and their staff. This team member is responsible for ensuring that surgical templates, interim prostheses, and diagnostic data are provided in a timely manner. The treatment planning conference can be arranged and treatment options documented for surgical and restorative dentists. By understanding these recommendations, the IC can also keep the patient abreast of how the case will proceed and establish a timeline for completion. A highly proficient IC can provide assistance to the restorative office by ordering prosthetic components or providing some items on loan. A system must be established and monitored to maintain sufficient inventory to meet these needs and to recoup these components after the restorative office no longer needs them. For example, autoclavable and reusable The two most important concepts for all team members to remember and utilize in conversations with patients about dental implants are: 1. The success rate of dental implants and 2. Bone atrophy following tooth extractions These two concepts play a vital role in educating the patient’s about the value of implant therapy. Many patients ask, “How long will my dental implants last?” All team members should be able to quote the 10-year success rate of dental implants as being at least 95%. The longevity of dental implants and their associated restorations qualifies implant therapy as the most successful of all treatment options. In addition to the success rate of implants, team members should reinforce the concept that bone atrophy is a predictable consequence when patients lose any or all teeth. The physiological response to tooth loss can be demonstrated with visual aid models (Figure 3-14, A), brochures, radiographs, or video examples (Figure 3-14, B). Role-play practicing by team members is highly recommended for gaining skill in effectively communicating these ideas to patients. Allocating sufficient time to rehearse the answers to patients’ questions allows all team members to speak with one voice. Their answers will become more confident and effective with continued practice. Scripts can be developed to review in staff meetings or at designated role-play rehearsals and are highly recommended when staff are having difficulty in answering particular patient questions.19,20 Conclusion Developing an implant mentality throughout the surgical or restorative office is a journey that starts with implementation of basic systems to promote the use and validity of implants. A solid foundation of team member support for the dentist’s advocacy of implants is vital to the success of these initiatives. However, sustaining an enthusiastic attitude toward implants requires constant reinforcement through team meetings, inhouse lectures and training, role-playing, and attendance at implant organizations. Dentists who commit to a continuous learning process in the implant field reap the rewarding status of increased growth professionally and financially. A sense of ownership pervades the practice that empowers team members to become more knowledgeable, professional, and organized in their pursuit of growth in the profession. Chapter 3 Essential Systems for Team Training in the Dental Implant Practice 39 B C A Figure 3-14. Examples of visual aids used to explain bone atrophy to patients. A, Mandible bone loss model set. B, The alveolus at the time of extraction of all maxillary teeth. C, The severely resorbed maxillary alveolus several years postextractions if no grafting and implants are employed. (A, Courtesy Salvin Dental Specialties, Inc. Charlotte, NC, 800-535-6566). REFERENCES 1. Misch CE: Contemporary Implant Dentistry, St. Louis, 1993, Mosby, pp 3-16. 2. Levin RP: The comprehensive approach to dentistry, AACD Academy Connection 13(Nov/Dec):6, 2007. 3. Strong SM: Treatment planning for the dental implant patient, Calif Dent J Cont Ed 56:35-39, 1997. 4. Levin RP: Updated systems are everything, Dent Econ 97(11):68-70, 2007. 5. Strong SM: The diagnostic workup: The forgotten key to success, Int Mag Oral Impl 2(3):18-22, 2002. 6. Krieger GD: Exceptional clinical photography, Dent Econ 97(12):54-59, 2007. 7. Haupt J: Guidelines for selecting the right all-ceramic material for a successful restoration, J Cosm Dentistry Fall:97, 2007. 8. Jameson C: Great Communication Equals Great Production, Tulsa, 2002, PennWell, pp 65-86. 9. Spear FM: Facebow Transfer Video, Seattle Institute for Advanced Dental Education, 2005. 10. Levin RP: The key to creating “WOW” customer service, Compend Contin Educ Dent 28(9):496-497, 2007. 11. Jameson C: Collect What You Produce, Tulsa, 1996, PennWell, pp 1-23. 12. Spiekermann H: Color Atlas of Dental Medicine, New York, 1995, Thieme Medical Publishers, pp 6-7. 13. Stoltz B. Tips for building. 14. Pride J: From Management Training for the Dental Practice series and personal communication. Pride Institute, Novato, CA 1988. An unstoppable team, J Cosm Dentistry Fall 70-71, 2007. 15. Strong SM, Strong SS: The dental implant maintenance visit, J Pract Hygiene 4(5):29-32, 1995. 16. Spiekermann H: Color Atlas of Dental Medicine, New York, 1995, Thieme Medical Publishers, pp 90-193. 17. Strong SM: Conversion from bar-retained to attachment-retained implant overdenture, Dentistry Today 25(1):66-70, 2006. 18. Strong SM, Callan D: Combining overdenture attachments. Dentistry Today 20(1):78-84, 2001. 19. Levin RP: Verbal skills, AGD Impact (Oct.):30-31, 2007. 20. Strong SM, Strong SS: Team training for the implant practice, Little Rock, AR 2007, 2007, Jetletter. Richard J. Rymond Ronald A. Mingus Charles A. Babbush C H A P T E R 4 DENTAL RISK MANAGEMENT Background Risk Management for Dentists Thousands of dentists each year are subjected to lawsuits alleging dental malpractice or to disciplinary actions instituted by state licensing boards. Certain risk management steps may be implemented by clinicians to minimize the risk of becoming subject to a claim for professional negligence and to minimize the risk of an adverse result if the dentist is in fact the subject of such a claim. Virtually every dental malpractice claim arises by virtue of a patient’s dissatisfaction with the outcome of treatment. However, the overwhelming majority of patients who experience a bad outcome never pursue a claim for monetary compensation; nor do they file complaints with state licensing boards. It is the authors’ belief that many claims that could have been brought are avoided through risk management practices implemented by individual dentists. Societal Forces Beyond the Control of the Individual Dentist Whether or not a dentist is subject to a claim for professional misconduct depends on multiple factors, some of which are within the practitioner’s control, and others that are not. There are three identifiable societal trends influencing the volume of litigation against dentists that are entirely beyond the control of the individual dentist: 1. The decline of the family dentist 2. The availability of legal services and 3. Competitive forces 40 Decline of the Family Dentist Over the last 50 years the family dentist’s role has changed. A generation or two ago, a family dentist typically was responsible for the majority of dental care rendered to an entire family and frequently to the extended family. The dentist could establish a personal relationship with each patient and keep track of the accomplishments and struggles of the patient’s family. The relationship was built as much on trust and friendship as it was on the quality of work and skill level of the dentist. For the most part, these patients would have found the thought of suing the family dentist repugnant. However, societal changes have diminished the role of the family dentist. The modern patient population is more transient, and the family dentist no longer has the opportunity to develop personal relationships with patients. It is now the exception, rather than the rule, for a given patient to see the same dentist over a period of decades. People change their residence more often than was usual in the past, and patients who move will be inclined to look for a new dentist who is closer to their new home. Dental insurance also leads to changes in the patient population. A far larger percentage of the patient population is now covered by dental insurance, and that new coverage availability frequently leads patients to change to a dentist who accepts their particular insurance plan. Changes in insurance coverage may give rise to the need for a change in dentists even when the patient does not move to a different geographic location. The dentist population is also more transient. Over the last 20 years or so, we have seen a substantial increase in the number of dental clinics, where there is a relatively frequent turnover in dentists, and where the patient may not see the same dentist at successive appointments. Chapter 4 41 Dental Risk Management Availability of Legal Services Attorney advertising, media attention to large jury verdicts and settlements, and overall acceptance of the idea that an individual should be compensated when harmed by another fuels lawsuits, particularly claims involving allegations of professional negligence. Late-night television viewers are bombarded with advertisements suggesting the availability of easy money from health care providers and their insurers; telephone books and billboards send the same message. Such advertising was once considered in poor taste and in many instances an outright violation of professional regulations and codes of ethics and conduct. It can be argued that this constant media blitz has also contributed to a decline in personal responsibility. Fifty years ago when a patient lost teeth, the patient assumed that this misfortune was attributable to inadequate personal hygiene, bad luck, or heredity. Currently, when a patient loses teeth there is a greater likelihood that the patient will place blame elsewhere and consider a claim against a dentist, alleging that with different or better care, the loss of teeth or dental disease would have been prevented. Competitive Forces Fifty years ago it was extremely rare for a dentist to criticize another dentist. Virtually every practitioner maintained an active and financially lucrative practice simply by servicing existing patients and new patients referred by those existing patients. Advertising by dentists and dental clinics has served to bring competitive market forces to the dental marketplace. The problem is compounded by the fact that, relatively speaking, the frequency of dental caries is substantially less than it was 50 years ago by virtue of the addition of fluoride to our water supplies. The treatment of caries was the “bread and butter” source of business for general dentists. In addition, insurance reimbursement programs have had a chilling effect on fees, and many dentists feel an overwhelming need to add to their patient base. In some instances, these competitive forces have resulted in a deterioration of professional decorum; dentists are far more likely today to criticize a prior treating dentist. Obviously, criticisms by one dentist toward another tend to promote controversy and litigation. Circumstances Within the Control of the Individual Dentist Although some claims and lawsuits may be unavoidable, the patient’s decision of whether to pursue a claim may be significantly influenced by the individual dentist. Meeting Patient Expectations Generally speaking, patients expect the dentist to provide them with the following: • A straightforward explanation of the proposed treatment and what they can expect • A reasonable opportunity to obtain answers to their questions about their treatment • Respect and consideration • Accessibility, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year • A clear understanding of their financial obligations and the potential changes in their financial obligations as treatment progresses and • A completely honest explanation of any complications In most lawsuits involving allegations of dental malpractice, a breakdown of the dentist-patient relationship has occurred long before the lawsuit is filed. Frequently, the breakdown in the relationship is attributable to what the patient perceives as inadequate communication. Most malpractice plaintiffs ultimately testify that the dentist failed to listen or respond to their complaints, or that the dentist treated them in an abrupt manner. Once a patient is unhappy with a dentist’s communication style, the patient is likely to seek care elsewhere. Very few patients consult an attorney and file a lawsuit without first severing the dentist-patient relationship. Furthermore, a large percentage of lawsuits are brought because a subsequent treating dentist criticizes the prior dentist’s treatment. The dentist who can maintain open communications with a patient is likely to be able to maintain an ongoing relationship, and the likelihood of a lawsuit or claim for dental malpractice in the face of an ongoing relationship is substantially diminished. Dealing With Bad Results Complications can and do occur in the practice of dentistry even under the best of care. Although the practitioner understands that complications can and do occur under the best of care and are often unavoidable, that explanation may not satisfy the patient or a jury. From a risk management perspective, the best time to address the possibility of a bad result with a patient is before the complication arises. A meaningful discussion with a patient prior to treatment about the most common potential bad outcomes can lessen a patient’s chagrin when a complication does in fact arise. A patient who is told about the possibility of needing root canal therapy before a dentist places a restoration or a crown is much more likely to be accepting of the need for root canal therapy when the need arises than is a patient who was never forewarned of the potential complication. Similarly, a patient who is advised of the numerous risks and complications associated with implant therapy before undergoing surgery is less likely to blame the dentist when the implant fails and/or a complication arises. The dentist’s response to a complication may determine whether or not the patient brings suit. A completely honest explanation of the reason for the complication or unsatisfactory result can diminish the patient’s anger and improve the likelihood that the dentist-patient relationship can be maintained. Maintaining the trust and confidence of the patient is essential. Avoiding Unnecessarily Aggressive Collection Practices Aggressive collection practices, whether initiated by the dentist’s office, a collection agency, or a lawyer, constitute recurrent themes in dental malpractice cases and state administrative actions. Prior to initiating a collection action, it is imperative 42 Chapter 4 that the dentist understand why the patient is refusing to pay. If a patient is satisfied with the treatment rendered but simply is unwilling or unable to pay, collecting what is owed is necessary for the operation of a profitable practice. On the other hand, a patient who feels (rightly or wrongly) victimized by substandard care and harassed by aggressive collection attempts often retaliates by filing a malpractice lawsuit and/or a complaint with the state licensing agency. Many dentists have come to regret their decision to pursue the collection of small account balances from patients who have retaliated by filing suit. Dental Malpractice Law The elements of proof required to establish a malpractice case are well established. Virtually every jurisdiction requires the patient/plaintiff to establish the following elements of proof: • Applicable standard of care • Deviation from the applicable standard of care • Causation • Injury or damage to the patient Unlike a claim for injuries arising out of a motor vehicle accident, in which the outcome of the case might be determined by the proof of a specific fact (i.e., was the light red or green?), the determination of the outcome in a malpractice case often hinges on subjective judgment. For example, the question of how many endosseous implants should be placed in the reconstruction of an upper jaw will hinge upon multiple factors including the professional judgment of the practitioner, the patient’s anatomy, the patient’s age, and perhaps financial considerations. Different practitioners may reasonably disagree as to an appropriate or ideal treatment plan. Seldom are the issues in a malpractice case the subject of a universally accepted standard of care. Typically, no singularly recognized textbook or universally accepted standard exists on which to rely to determine the standard of care. Rather, the ultimate determination of every issue in a malpractice case typically hinges on the opinion testimony of dental health care providers. Similarly, determining the extent of any injury or damage will often be subject to opinions and interpretation, as will causation. Although a patient may establish that a dentist has rendered inappropriate care under a given set of circumstances, the patient may not be able to establish injury or damage. The standard of care in a malpractice case is often subjective. Generally, the law provides that a dentist has an obligation to use the skill and care ordinarily exercised by other dentists under the same or similar circumstances and to refrain from doing those things that such a dentist would not do. Similarly, the law provides that the standard of care for a dental specialist is the standard of care ordinarily used by other specialists under the same or similar circumstances. Typically, written guidelines such as those published by the American Dental Association (ADA) or a specialty organization or those contained in the literature will constitute evidence, but not proof, of the requisite standard of care. Because the concept of standard of care is typically subjective, most courts require that the standard of care be estab- Dental Risk Management lished by expert testimony. The law regards the substance of testimony in malpractice cases to be of such a technical nature that only an “expert” is sufficiently knowledgeable to offer evidence as to the standard. Most jurisdictions accept the testimony of practicing dentists as expert testimony. The specific qualifications of dentists who offer expert testimony will typically have some bearing on the weight that the jury or fact finder gives to their testimony; however, any licensed practicing dentist will typically qualify as an expert. Many jurisdictions place minimal requirements on the qualifications of the proposed expert witness, but those minimal qualifications are typically satisfied without difficulty. By way of example, several states require that the expert spend at least 50% of his or her professional time in the clinical practice of dentistry or teaching dentistry at an accredited dental school. The law recognizes that dentistry is inexact and has been described as part art and part science. There are different methods that dentists may reasonably use, and there are different schools of thought concerning the different methods that are available. Thus the fact that another dentist might have used a different method of treatment will not typically establish a deviation from the standard of care. The law also recognizes that complications occur under the best of care. Therefore the mere fact that a patient experiences a bad result will not typically establish a deviation from the standard of care. In short, the law recognizes that professional judgment may play a role in dental treatment. Although the determination of the standard of care is typically subjective, there may be instances in which certain acts or the failure to perform certain acts in the care and treatment of a patient would be difficult to defend. By way of example, it would be very difficult to defend the proposition that a dentist does not need to obtain some sort of health history and dental history before initiating treatment or prescribing medications. Similarly, it would be difficult to defend the proposition that a dentist need not take radiographs before initiating certain procedures, and some would argue that annual radiographic examinations along with periodic full mouth radiographic examinations are required by the standard of care. In addition, certain types of implants have fallen out of favor and are considered by many practitioners to be outdated to the extent that their use would be difficult to defend (e.g., the routine use of subperiosteal implants in the maxilla). The individual practitioner has an obligation to remain current on the standard practices being used by other dentists under the same or similar circumstances. The more widely accepted a given practice, the more likely it is that a jury will find that the specific practice is required by the standard of care and that failure to conform to that practice is professional negligence. The plaintiff in a dental malpractice case must also establish causation and damages, usually through expert testimony. Often, the question of causation is rather straightforward, but the question of damages can be complex. Because most dental malpractice cases involve complications associated with dental procedures, the system recognizes that patients are typically in a compromised state before the alleged “mistake.” For example, Chapter 4 43 Dental Risk Management in cases in which patients claim that their diet is limited as a result of the inability to masticate adequately with recently placed implants, a meaningful evaluation would require that the attorneys and fact finders (1) compare the patients’ current claimed limitations with any limitations that might have been present before treatment; and (2) determine any limitations that would have developed in the absence of implant placement. State Administrative Licensure Actions Although being sued for dental malpractice can be an unpleasant, time-consuming, and costly experience, an action brought by a state licensing board can have an even greater negative impact on a dentist’s practice. Every dentist practicing in the United States is subject to the rules and regulations established by state licensing boards. Such boards have been established to protect the public by ensuring that those rendering dental care and treatment to patients are competent and qualified. Typically, such boards and agencies have the authority to establish educational prerequisites for obtaining a license to practice dentistry, dental hygiene, or other auxiliary dental treatment; establish continuing education requirements; and set specific rules and regulations that limit the scope of practice for general practitioners and specialists. Such boards and agencies also have the authority to reprimand, suspend, and revoke the licenses they issue. Unlike claims for dental malpractice, which are generally tried before a judge and/or jury, state license administrative actions are generally investigated by the state licensing agency, and the determination of whether disciplinary action is warranted is initially made by the board or agency. A dentist who is dissatisfied with the ruling from the board or agency generally has the right to appeal any adverse ruling through the court system. However, the specific procedure varies among jurisdictions. Between 1990 and 2004 a total of 9986 reports were made by state licensure boards to the National Practitioner Data Bank.1 The vast majority of these reports involved issues in which the dentist’s license was revoked, suspended, or placed on probation. Other disciplinary actions subject to such reports include formal reprimands or censure, and rulings excluding the dentist from participating in federal programs.1 Common charges brought against practitioners by state boards include allegations of violations of the standard of care, practicing while impaired by drugs and/or alcohol, failing to meet continuing education requirements, fraudulent billing practices, and practicing beyond the scope of the dentist’s permitted area of practice. The severity of the discipline imposed depends on a multitude of factors, including the seriousness of the offense, the number of offenses, whether the dentist has a history of infractions, and the presence of any mitigating factors. The severity of punishment can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Further, in any given year, the aggressiveness of any given state board or agency can vary depending on the philosophies of the personnel who have enforcement authority. State regulations generally require the license holder to fully cooperate and assist state board investigators when requested. At a minimum, such cooperation requires dentists to provide patient records to investigators pursuant to proper requests for such information and to permit inspection of the dentist’s office and equipment. It is strongly advised that any dentist who is the subject of a dental board investigation consult with legal counsel knowledgeable and experienced with dental board proceedings to ensure the integrity and fairness of the process, because often the state board has both prosecutorial and judicial authority. Many professional liability insurance polices provide coverage for attorney fees and expenses associated with administrative actions. Risk Management Practices Documentation The most important aspect of risk management involves proper documentation. Most claims alleging dental malpractice, as well as state board investigations, are initiated by a request from an attorney or board investigator for a copy of the dentist’s records. Typically, the attorney and/or health care provider will review these records before determining whether or not to bring a claim on behalf of the patient. Similarly, the records will be reviewed by someone on behalf of the state board before determining whether administrative charges are warranted. Proper documentation will significantly reduce the likelihood that the matter will escalate to a lawsuit or administrative charges; poor documentation practices will have the opposite effect. In lawsuits that are filed, proper documentation will significantly reduce the risk of an adverse outcome. What Should Be in the Records? Good risk management practices require the dentist to include the following in his or her records: 1. Meaningful discussion. A meaningful discussion includes the dentist’s objective findings and the patient’s subjective complaints. For the records to be “meaningful,” all abnormal findings and test results should be included. The dentist should document all positive findings essential to the dentist’s diagnosis and all findings essential to the development of the treatment plan. Negative findings or findings that are within normal limits may be necessary to create a meaningful record, depending upon the circumstances. The question of whether to include negative findings should hinge primarily on the practitioner’s judgment. Negative findings that are important considerations in making a diagnosis or developing a treatment plan should be recorded. 2. Diagnosis. The records should contain a meaningful discussion of the dentist’s diagnosis. The extent of the records concerning the diagnosis will hinge on the nature of the patient’s visit. An emergency examination of a new patient with pain in the area of a single tooth will obviously create a record far different from a record created for a new patient seeking a comprehensive initial 44 examination. To ensure that the records concerning the diagnosis are meaningful, it may be necessary for the dentist to incorporate either a reference to or a discussion of the process whereby the diagnosis was reached. This reference may necessitate a comment concerning the differential diagnosis and the manner in which the final diagnosis was reached. Frequently, the dentist’s diagnosis can be implied from other documentation and evidence in the chart. For example, a notation of “DL amalgam no. 19” together with a radiograph showing a radiolucency on the clinical crown of tooth no. 19 reasonably implies a diagnosis of decay on the distal and lingual surfaces of tooth no. 19. While such documentation is sufficient for one knowledgeable in dentistry to decipher the dentist’s diagnosis, this connection may not be made by the person who is reviewing the dental records to decide whether a lawsuit will be filed. 3. Treatment plan. A review of the dentist’s records should clearly reveal the nature and extent of the proposed treatment plan. To the extent that alternative treatment plans may be viable, they, too, should be contained in the records, along with the selection criteria for the ultimate treatment plan. For example, the treatment options for the patient with an edentulous lower arch are implants or a full lower denture. It is appropriate for the dentist to state in the records that the options were explained. The records should also document the manner in which the ultimate treatment plan was reached (e.g., options of implants versus dentures were discussed; patient selects dentures based on cost). 4. Treatment. The records should contain a meaningful explanation of the treatment rendered. Typically, this explanation will be contained in the dentist’s progress notes. Other vehicles are also available, such as a colorcoded dental chart. If the progress notes are prepared, in part or in whole, by someone other than the treating dentist, these progress notes should be reviewed for accuracy. At a minimum, the progress notes should contain a description of the treatment rendered on a given date. Depending on the circumstances, the dentist should consider including reference to the possible need for future treatment (e.g., deep filling, patient may require endodontic procedures) and follow-up instructions to the patient (e.g., patient is instructed to call if tooth remains painful). Because there are an infinite number of treatment scenarios, it is impossible to completely and accurately advise the dentist concerning all the information that should be contained in a progress note. However, a good rule of thumb is, if the progress notes do not contain information concerning an aspect of treatment or discussion with the patient, in a lawsuit it will be argued that the treatment or discussion did not occur. The patient and attorney bringing suit will argue that what the dentist failed to chart did not happen. 5. Outcome. In many circumstances, it is appropriate for the dentist to include an entry in the records concerning the outcome of treatment. A complication that occurs Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management during treatment should certainly be included in the progress notes. On the other hand, it may be appropriate for the dentist to comment that the patient is satisfied with the treatment. Although such an entry is probably not appropriate for the case in which the dentist places a simple restoration, an entry of this nature can be very important if the dentist has rendered restorative care in an effort to address aesthetic or functional deficiencies, such as where an implant and prosthesis are placed. When complications occur, they should be documented objectively. Generally, the dentist should not document opinions unless facts support the opinions. The progress notes also should be objective in nature. Unless the dentist is convinced as to the cause of a specific complication, the cause should not be documented. As a final rule of thumb, when the dentist is in doubt as to what should be included in the records, the matter under consideration should be included. Noncompliance Any noncompliance on the part of the patient should be documented. All failures to appear for appointments and canceled appointments should be recorded. If a patient refuses a recommendation for a consultation with a specialist, this must be included in the records. If a patient refuses recommended treatment, this also must be included in the records. These entries should be recorded in objective language. Furthermore, where appropriate, the dentist may want to generate additional documentation concerning noncompliance by the patient. For example, if a patient is instructed to return for radiographic examination 1 year after the placement of implants and the patient fails to appear, it may be appropriate for the practitioner to send a letter to the patient explaining the concerns and risks associated with the failure to return for follow-up evaluation (e.g., a delay or failure in diagnosing infection leading to implant failure). Scope of Records Many dental malpractice claims arise out of an alleged failure on the part of the dentist to maintain adequate pretreatment records. These records include meaningful health history findings (periodically updated), dental history findings, allergies, general descriptions of existing restorations, and evaluation of the periodontal health of the patient. The practitioner should be aware of the records generated and maintained by other members of the profession. Communications With Patients The dentist should record all substantive discussions with the patient or the patient’s family, including telephone conversations. As discussed, most lawsuits involving allegations of dental malpractice involve a breakdown of the dentist-patient relationship involving inadequate communication. Generally, the dentist should be aware that all patients expect to be treated Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management with dignity and respect. It is never appropriate to make a demeaning comment to a patient. Furthermore, patients will take offense if they do not believe that their dentist is giving them the time they need to discuss the status of their dental health, proposed treatment, or complications associated with treatment. Every dentist should try to make patients feel that they are given all of the time they require. In the event that the patient experiences a complication, it is important for the dentist to offer an honest explanation of the complication and the proposed curative treatment. The dentist who shows genuine concern for the patient and who proposes appropriate follow-up is far less likely to be the subject of a claim for malpractice than the dentist who fails to make certain that the patient fully understands what has occurred. From time to time, the dentist will be directly or indirectly involved with other health care providers or other dentists involved in the patient’s care. The dentist should take time to communicate appropriately with these other care providers. Communications with other dentists or health care providers (e.g., discussions concerning a patient’s cardiac status) should be documented in the records. The subject of informed consent is discussed at length later in this chapter. However, in terms of patient communications, the dentist should be aware that it is inappropriate to make the patient a guarantee or promise concerning the outcome of any proposed treatment. Irrespective of the skills of the dentist, complications can and do occur. Representations by the dentist that are not ultimately fulfilled will be a source of extreme dissatisfaction to the patient that could lead to litigation. This is particularly true in implant dentistry because implants involve the placement of artificial materials in the body, and the body’s physiological reactions to these artificial materials is not entirely predictable. Under no circumstances should a dentist make adverse unprofessional comments concerning a patient to other health care providers or in the records. Comments in the chart (e.g., the patient is neurotic or a hypochondriac) can significantly compromise the defense of a claim involving allegations of professional negligence. Record Retention Many jurisdictions have statutes setting forth a minimum period of time during which dentists or other health care professionals are required to maintain records. From a risk management standpoint, it is strongly recommended that all patient records be maintained permanently. Unfortunately, in many jurisdictions there is no absolute time limit as to when a claim for professional negligence may be brought against a dentist. In the event that a claim is filed and the treatment records are no longer available, the ability to defend the dentist will be significantly compromised. Alteration of Records Records should never be changed in anticipation that a patient is pursuing, or might pursue, legal action. However, sometimes 45 it is appropriate for dentists to make corrections to their treatment records to correct an inaccuracy or to supplement an entry with additional information. When good record-keeping practices dictate that corrections are made, corrections should be added without obliterating or destroying earlier entries. Furthermore, any corrections to a record should be initialed and dated. Under no circumstances should any correction be made to any record once the dentist is placed on notice of a possible claim. The effect of making a change to a record, particularly a change that alters the meaning of a prior record or obliterates a prior record, often gives the appearance that the dentist is trying to cover up something or make excuses. Many jurisdictions permit the award of punitive damages when a fact-finder determines that changes have been made to the record, at least in those instances when it is determined that the changes were made in an effort to conceal a pertinent fact. It is common practice for the plaintiff ’s attorney to carefully inspect a dentist’s original records. There are a number of scientific methods available to attorneys for testing the timing and legitimacy of record-keeping entries. For example, forensic handwriting experts can be retained to test whether two different entries were written with the same pen, the age of the ink in the entries, and the contents of any obliterated entries. Moreover, in situations in which a document is destroyed or removed from the chart, the existence of the document can sometimes be re-created through indentation analysis. Setting aside the fact that the improper alteration of records is dishonest, many tools exist that will enable opposing attorneys to detect alterations, and nothing is more disastrous to a physician’s defense than to be caught improperly altering records. If a dentist perceives a need to change any record substantively, and has not consulted with an attorney or appropriate risk management professional concerning the appropriate manner in which to make corrections to a chart, it is recommended that the dentist consult with counsel or other qualified risk management professional. Risk Management Practice Pointers • Records should clearly support all diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. • The chart should be legible and easy to read, not only to the practitioner but to any other reasonable person reviewing the chart. • All abnormal findings and test results should be clearly recorded in the chart. • Entries prepared by support staff should be reviewed and corrected as necessary. • All consultations should be recorded in the chart. • All referrals should be recorded in the chart. • Entries should be objective and never demeaning toward the patient. • All addenda and corrections in the chart should be dated and initialed. • Corrections to the chart should not be obliterated; a single line should be drawn through any incorrect entry. 46 • As a rule of thumb, if it is not in the chart, an opposing attorney will claim that it did not happen. • Noncompliance by the patient should always be recorded in the chart. • To the extent possible, records should be maintained permanently. • All substantive communications with the patient should be charted. Informed Consent Informed consent is a doctrine of law that proceeds from the assumption that no one may touch another person without that person’s consent. In a professional relationship, courts hold that a health care provider may not touch (or treat) a patient unless the patient has been informed of what the health care provider intends to do by way of treatment. Specifically, the law requires the health care provider to disclose to the patient the nature of the proposed treatment, the anticipated benefits of the proposed treatment, the potential material or significant risks of the proposed treatment, and treatment alternatives so that the patient may make an “informed decision” as to whether to submit to the treatment. Not all risks, benefits, or alternatives need to be explained. The law provides that the most common complications must be explained, along with reasonably foreseeable serious complications. The risks that must be explained to a patient can vary depending on the specifics of the patient and the procedure to be performed, and there is often significant disagreement among practitioners as to what risks are significant enough that they need to be explained to the patient. Similarly, only reasonable alternatives need to be explained. In most jurisdictions, the law does not require a written informed consent. However, the use of a written informed consent form, signed by the patient, provides proof that the patient was provided with the information. As a result, most dentists now use some form of a written informed consent before proceeding with more invasive types of treatment (e.g., extractions, implants, orthodontics). When a general dentist performs a procedure that falls within the field of a specialist, the general dentist is held to the same standard as the specialist. Therefore, arguably, the general dentist also should inform the patient of his or her right to be treated by a specialist for the proposed treatment. For example, some patients may be unaware that there are specialists who limit their practice to endodontic procedures; these patients should arguably be informed of their right to see a specialist before the general dentist initiates such treatment. In most jurisdictions, for a patient to prevail on a claim against a dentist on a theory of lack of informed consent, the patient will need to demonstrate that, had the patient been informed of the appropriate risks, benefits, and alternatives, the patient would have elected against proceeding with the treatment. Different jurisdictions vary on whether patients are required to establish that they would have elected against treatment, or whether they must establish that a reasonable person would have elected against treatment, or both. Typically, a Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management claim against a health care provider that is based exclusively on a theory of lack of informed consent is regarded as doubtful. More often, a claim against a dentist will incorporate this theory along with a claim that the treatment itself fell below the standard of care. Iatrogenic Complications Every dentist is capable of making a mistake, and all dentists will have patients who experience complications associated with treatment. Complications may be attributable to an unexpected reaction by the human body to treatment, an unforeseeable complication of a given procedure that sometimes occurs under the best of care, poor patient compliance, or the dentist’s treatment. Even when the complication or injury is attributable to the dentist’s treatment, the dentist may have acted in accordance with the standard of care. The dentist should proceed cautiously when it is possible that an injury may have occurred. The dentist’s first concern should be for the patient’s well-being. The dentist should speak honestly with the patient concerning the nature of the complication or injury. However, before the dentist expresses any self-criticism, it is appropriate to consult with an attorney or a professional liability insurance carrier. Dentists should choose their words carefully in speaking with patients about the cause of any complication or injury. Statements by the dentist can easily be interpreted as an admission of negligence. Although in certain circumstances it would be appropriate for the dentist to make such an admission to the patient, such an admission should be made only after thoughtful consideration. When a patient experiences an injury during the course of dental care, it is important for the dentist to save all evidence that may be relevant to a potential claim. If the injury is associated with dental equipment, the equipment should be preserved. Some jurisdictions require dentists to report equipment failures to a state agency and/or manufacturer so that dangerous products can be modified or discontinued. If the injury involves the loss of teeth or supporting bone, these should be saved as well. In the event that the dentist chooses to consult with an attorney or insurance company representative, it would be inappropriate to include any notation concerning these discussions in the records. Although the dentist may want to create a record concerning these discussions, such discussions are not directly related to patient care and will typically be regarded as privileged. Entries such as “called insurance company representative” or “called attorney” should never appear in a patient’s chart; rather, correspondence and records concerning oral communications with an attorney or insurance carrier should be maintained in a separate legal folder. Information concerning a consultation with an insurance carrier or attorney should be for the practitioner and legal counsel only. Responding to the Adverse Inquiry From time to time, a practitioner will receive inquiries from attorneys along with requests for copies of patient records. In Chapter 4 47 Dental Risk Management all likelihood, the immediate reaction will be one of concern. However, most inquiries or requests will be unrelated to any claim concerning treatment. The requests may be triggered by any of the following: 1. The attorney may be representing the patient in a personal injury case arising out of a motor vehicle accident, from a slip and fall incident, or from a work-related injury. If there is any concern about a possible dental injury, the attorney will request copies of records from all dentists involved in the care and treatment of the patient both before and subsequent to the incident giving rise to the claim. The dentist’s records may have some relevance to the claim being asserted against a third party. 2. The patient may be considering bringing a claim against some other dental health care provider who either preceded or succeeded the involvement of the patient’s current dentist. Because the attorney representing the patient is required to establish the patient’s dental condition preceding the claim and the injuries arising out of the claim, the records of all involved dental health care providers will be requested. 3. When a patient has brought a claim against a third person claiming dental injuries arising out of some form of trauma (e.g., from a motor vehicle accident), the attorney representing the adverse party may request the dentist’s records in the event that the patient’s attorney fails to do so. 4. If a patient has brought a claim alleging dental malpractice against a former dentist and if the patient’s attorney neglects to request the records of the latter dentist, the attorney representing the defendant dentist is likely to request the records. A practitioner may be unable to determine from the request the reasons the records are being sought, but if the requesting attorney has supplied an appropriate authorization form a complete copy of the records should be forwarded to the requesting attorney. A practitioner is typically permitted to charge a fee for the duplication of records; however, this charge should not be excessive. Some states regulate the amount that practitioners can charge for providing copies of records. In the event that there are questions concerning the request, or if the expense associated with duplicating radiographs or study models is such that the dentist wants to make certain that the requesting attorney will pay the duplication fees, it is reasonable to contact the requesting attorney. The practitioner’s conduct should always be courteous and professional. Absent an authorization from the patient, the practitioner should not discuss the treatment with the requesting attorney. Under no circumstances should original records ever leave the dentist’s custody in response to such a request. Furthermore, no addendum or modification of records should be made after the dentist is served with such a request. If the dentist observes some potential deficiency in the patient file, a note concerning this observation may be made and maintained in a separate legal file. Unfortunately, such requests may also be triggered by a concern regarding the quality of care rendered to a patient. The response to such an inquiry should not differ in form or substance from any response from any attorney requesting patient records. Response to the request should be reasonable and timely. If there is reason to believe that the request may be triggered in part by a question concerning the quality of care, the practitioner may want to discuss the inquiry with either an attorney or a professional liability insurance carrier before preparing a formal response. Under no circumstances should the practitioner engage in conduct that may “add fuel to the fire” or discuss the quality of care, the patient’s poor compliance, or any other subject that may be deemed argumentative or defensive. Statute of Limitations In most jurisdictions, claims for professional negligence or dental malpractice are covered by a 1- to 3-year statute of limitations. Historically, it was a rather simple matter to determine when the statute of limitations began to toll; typically, the cause of action accrued on the date on which treatment for the condition at issue was last rendered. However, many jurisdictions have established what is often characterized as a “discovery rule.” Under this rule, the cause of action accrues on the date on which the patient discovers, or in the exercise of reasonable care should have discovered, that an injury is the result of improper dental care. Some jurisdictions have a vehicle whereby the statute of limitations can be extended by placing the dentist on notice that the patient is considering bringing a cause of action. Moreover, in most jurisdictions the statute of limitations for pediatric patients does not begin to run until the patient reaches adulthood. Whereas most lawsuits are brought within 1-2 years of the treatment in question, there are situations in which lawsuits are brought 10 or even 20 years after treatment is provided. In the event that a practitioner receives any sort of correspondence from a patient or an attorney that explicitly or implicitly threatens some sort of claim, the dentist’s malpractice insurance carrier should be placed on notice. Many professional liability insurance policies require that the carrier be immediately notified upon receipt of any threatened claim; failure to do so can jeopardize insurance coverage under some circumstances. Financial Considerations of the Patient Although statistics are not readily available, it can be reasonably estimated that approximately 20% of all dental malpractice claims are triggered in response to collection efforts on the part of the treating dentist. These collection efforts may simply involve correspondence or telephone calls from the dentist’s office, or they may include the involvement of a collection agency or collection attorney. Whenever a patient is dissatisfied with the results of his or her dental treatment and is then confronted with what are perceived as aggressive collection efforts, the patient may be inclined to challenge the quality of care received by asserting a claim for dental malpractice or by 48 filing a complaint with a state dental board or local dental association. By virtue of the foregoing, and as a risk management technique, it is essential that the dentist weigh and balance the competing considerations that may be associated with collection efforts. 1. When the dentist believes that the patient may be understandably dissatisfied with treatment, in spite of the fact that the dentist believes that the quality of care was reasonable, the dentist may want to consider waiving a fee balance or forgoing collection efforts. From a risk management standpoint, it does not make a difference whether the patient’s perceived dissatisfaction is justifiable. If the dentist wants to reduce the likelihood of a retaliatory complaint, the dentist may want to consider a conservative approach to collection efforts. 2. As previously indicated, statutes of limitation might preclude or substantially limit a patient’s ability to pursue a claim alleging dental malpractice. It is important for any dentist who is proceeding with collection efforts to be aware of the statute of limitations. By postponing aggressive collection efforts until after such time as a claim alleging dental malpractice would be otherwise barred by the applicable statute of limitations, the dentist will take advantage of a technical defense to any potential counterclaim that might not otherwise be available. If the dentist lives in a jurisdiction in which the statute of limitations for a dental malpractice claim is 1 year and the statute of limitations for pursuing a collection action is 4 years, waiting at least 1 year from the date on which the dentist last saw the patient before bringing a collection action will serve the best interests of the dentist. Because many collection agencies and collection attorneys lack experience and knowledge concerning statutes of limitation for professional claims, it is advisable for the dentist to consult with personal counsel before initiating any collection efforts. 3. Finally, in considering the issue of fee disputes giving rise to malpractice claims and state dental board complaints, the dentist should consider adopting a “satisfaction guaranteed” policy. Such a policy has worked wonders for major retailers, and in this competitive environment, the benefits of instituting such a policy may outweigh the costs. From a practical standpoint, many dentists have adopted such a policy on an informal basis; that is, when a patient is dissatisfied with treatment, many practitioners will essentially write off the balance owed by the patient, whether or not the patient’s dissatisfaction is justified. From a risk management standpoint, this is an advisable approach. The appropriateness of such an approach will presumably depend on the nature of the practice and the individual practitioner. The practitioner may adopt such a policy on a case-bycase basis. It is common to encounter a patient who simply cannot afford appropriate treatment. However, under no circumstances should the patient’s perceived financial limitations limit the recommendations made by the dentist or limit the Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management presentation of alternative treatment plans. In short, it is not up to the dentist to decide that a patient is unable to afford periodontal care, crown and bridgework, implant reconstruction, root canal therapy, or any of the other modalities of treatment that are available to a more affluent patient. If the ideal treatment plan for a given patient includes the preparation of crown and bridgework at a cost of $10,000, the patient should be given this option; if the patient indicates that the proposed treatment is beyond his or her financial abilities, the dentist should record the patient’s statement and present alternatives. Thus it may be appropriate for the dentist to prepare an entry that reads as follows: “Patient advised that crown and bridgework would be the ideal treatment plan: gave estimate of $8500. Patient states unable to afford crown and bridgework: less expensive options discussed. Patient elects removable partial denture.” In short, the standard of care in terms of providing treatment options is no different for a “prince” than for a “pauper.” Frequent Allegations Several studies have explored the types of lawsuits alleging dental malpractice. Table 4-1 summarizes a 2005 survey of 15 insurance companies, insuring a total of 104,557 dentists, conducted by the American Dental Association detailing the percentage of paid claims arising from a variety of treatments.2 Before the 2005 ADA survey, Charles Sloin, DMD, an expert in dental risk management, conducted an unpublished study of more than 1200 dental malpractice claims resolved between January 1, 1987, and December 31, 1995. Table 4-2 breaks down the type of claim as a percentage of the total number of claims asserted against those insured by one dental malpractice insurance carrier.3 Although claims against dentists for negligent implant placement comprised a relatively small percentage (2.9%) of TABLE 4-1 Summary of 2005 American Dental Association survey detailing the percentage of paid claims arising from a variety of treatments Type of treatment Percentage of paid claims Crown and bridge Root canal therapy Extractions Dentures Oral exams Implants Orthodontics Periodontal surgery Treatment of TMJ Other 21.8% 20.0% 19.3% 6.7% 5.1% 2.9% 2.0% 1.4% 0.2% 20.6% 100% Data from American Dental Association: Dental Professional Liability: 2005 survey conducted by the ADA Council on Members Insurance and Retirement Programs. Chapter 4 49 Dental Risk Management TABLE 4-2 Unpublished study by Charles Sloin, DMD, of dental malpractice claims Type of claim Endodontia Exodontia General dental treatment Crown and bridge Orthodontia Failure to diagnose or treat periodontal disease Full or partial dentures Major oral surgery Anesthesia Dental implants Corporate claims Miscellaneous Percentage of the total number of claims 18.8% 13.2% 12.0% 10.5% 9.2% 6.1% 4.6% 2.2% 2.1% 1.6% 9.1% 10.6% Data from Charles Sloin, DMD: Personal communications, unpublished study, 2000. all claims paid from 1999 to 2003 by dental malpractice insurance carriers on behalf of all dental practitioners, allegations of negligent implant placement comprised a higher percentage of litigation against oral surgeons. It is believed that this is due to the fact that oral surgeons perform far more implant procedures than general dentists. According to Gwen Jaeger, a risk management expert with OMSNIC, a mutual insurance company that insures oral and maxillofacial surgeons, claims alleging negligent care and treatment related to dental implants comprised 9% of all claims made against OMSNIC insureds. Of these claims, 79% are resolved in favor of the defendant oral surgeon without any payment to the claimant.4 Based on the experience of the authors of this chapter, it is clear that the number of claims relating to implant dentistry has increased, primarily due to the fact that implants are being offered to more patients, and greater numbers of dentists are performing implant procedures. Incidence of Payments Made to Settle Claims for Dental Malpractice Claims for dental malpractice are primarily settled by two groups of payors: (1) dental malpractice insurance carriers, and (2) dentists themselves. Statistics have been kept by the federal government since 1990 regarding the incidence of payments made by dental malpractice insurance carriers to settle claims for malpractice pursuant to federal law that requires malpractice insurance carriers and other entities to report the settlement of all malpractice claims to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB). However, dentists who settle claims for malpractice with their own funds are not required to make reports to the NPDB. Thus, while statistics do exist on payments made by dental malpractice insurance carriers since 1990, no such statistics exist on payments made by dentists to settle claims with their own funds. The 2004 Annual Report of the NPDB provides some interesting statistics on reported payments to settle malpractice claims on behalf of dentists. Between 1990 and 2004 a total of 35,514 payments to settle malpractice claims on behalf of dentists were reported to the NPDB.5 The vast majority (78.6%) of all reported malpractice payments from 1990 to 2004 were on behalf of physicians, 13.3% of the payments were made on behalf of dentists, and 8.1% of the payments were made on behalf of other health care practitioners.5 Nationwide, on average, for every one payment report made to the NPDB on behalf of a dentist, there were six payment reports for physicians.6 Certain states (California, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin) saw a greater percentage of reports being made against dentists as compared with physicians. Other states (Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, and West Virginia) show a lower frequency of payments being made on behalf of dentists when compared with physicians.7 Nationwide, an average of 2159 malpractice payments on behalf of dentists were reported to the NPDB each year from 2000 through 2004. This figure does not include payments made by dentists themselves to settle claims.8 Complications Associated With Crown and Bridgework Claims for ill-fitting or failed crowns and bridgework are, statistically speaking, the most common types of claims asserted by patients against dentists. The most common criticism, in the authors’ experience, are allegations of defective and/or open margins. In situations where a grossly open margin is shown on radiographs, such claims are difficult to defend. However, in most instances such claims result in minimal damages since these patients rarely have any permanent injury. Rather, the damages are generally limited to the costs associated with necessary corrective treatment, as well as the inconvenience and discomfort experienced by the patient who requires a second procedure. Many dental malpractice claims involve allegations to the effect that restorative work is aesthetically unsatisfactory. Examples include patient dissatisfaction with the appearance of crowns, bridges, and dentures. When restorative work is performed, the practitioner may want to ask the patient to sign off on the aesthetics after the try-in phase and before the final prosthesis is permanently cemented into place. After the completion of prosthodontic care, it is appropriate for the dentist to comment in the records on the aesthetic result and the patient’s level of satisfaction. Complications Associated With Root Canal Therapy Many malpractice cases arise by virtue of failed root canal therapy. Most lawsuits involving allegations of faulty root canal therapy involve claims that an inappropriate technique or material was used, or that the tooth was underfilled or overfilled. Other common complications of endodontic therapy include perforations of the root, broken instruments, 50 and root fractures. Although many dentists regard most or all of these complications as events that can occur with reasonable care, it is equally clear that these complications can occur as a result of substandard care. When the patient experiences a common endodontic complication, the complication should be recorded in the chart and the patient should be honestly apprised of the complication and given appropriate recommendations for follow-up care. For the general dentist, it may be appropriate to refer the patient to a specialist or at least to provide the patient with this option. Complications Associated With Extractions Common complications associated with extractions include infection, damage to adjacent teeth, removal of the wrong tooth, paresthesia, jaw fractures, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injuries. Patients should be informed of the potential risk of these complications before the teeth are extracted, preferably in writing. Once the complication occurs, the practitioner should consider referring the patient to an appropriate specialist should the necessary corrective treatment be outside the practitioner’s expertise. As with root canal therapy, most of these complications can occur with reasonable care, but many patients will claim that the complications are attributable to substandard care. Failure to Diagnose Periodontal Disease Claims alleging a failure to diagnose and treat periodontal disease seem to have decreased over time. Sloin found in his survey that claims alleging a failure to diagnose or treat periodontal disease comprised a total of 6.1% of all dental malpractice claims paid between the years 1987 and 1995. However, that specific allegation of malpractice was not deemed to be sufficiently common enough to warrant its own subcategory in the 2005 ADA survey. While claims for failing to diagnose/treat periodontal disease may be included within the “Other” category in the 2005 ADA survey, the authors’ collective experience has found that claims alleging a failure to diagnose/treat periodontal disease comprise a smaller percentage of the overall claims against dentists than occurred in the 1990s. This may be due to more attention by dentists to the possibility of tooth loss being caused by periodontal disease rather than by decay, as well as to patients’ improved oral hygiene practices related to gum disease (i.e., flossing). For the general dentist in particular, it is generally recommended that the pretreatment periodontal status of each patient be addressed somewhere in the treatment records. Once the general dentist makes the diagnosis of periodontal disease, the diagnosis should be recorded and the patient should be given treatment options. This information should also be recorded in the chart, as should the patient’s clinical response to treatment. If the patient is referred to a specialist Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management and the patient refuses to follow up on such a referral, this too should be recorded in the chart. Temporomandibular Joint Injuries Many dental malpractice claims involve allegations that either the musculature or the joint itself has been damaged as a result of treatment. The mechanism of injury may range from microtrauma, which may be caused by improper occlusion, to macrotrauma, which may be directly caused by trauma associated with an extraction of mandibular teeth or related to other trauma such as a motor vehicle accident, assault, or fall. Temporomandibular joint injuries are particularly difficult to evaluate in many cases because of their subjective nature and the disagreements of those in the dental profession as to their appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Many dentists hold the view that all patients should be evaluated for TMJ disorders on a periodic basis. If a TMJ disorder is diagnosed or discovered by history or through examination, it should be recorded along with treatment recommendations, if any. Orthodontic Injuries Claims against orthodontists and general dentists performing orthodontic care generally involve the following: (1) allegations of TMJ injuries, (2) undiagnosed deteriorating periodontal health, (3) undiagnosed areas of decalcification or decay leading to the need for restorative care, (4) failure of orthodontics secondary to poor treatment planning, and (5) undiagnosed root resorption leading to tooth loss. Most dentists hold the view that it is appropriate to provide the patient with a detailed account of potential complications before initiating orthodontic care. Many orthodontists use a standard informed consent form that summarizes potential complications. In addition, because patient compliance is such a critical factor in the outcome of orthodontic care, it is important for the dentist to convey to the patient the need for good compliance and the risks associated with poor compliance. These communications should be documented. When a patient fails to provide reasonable compliance, potential ramifications should be communicated to the patient and a record of noncompliance should be documented in the chart. If the practitioner is treating a minor, the foregoing communications should involve the parents. Inadequate Radiographs Often, claims of undiagnosed conditions arise by virtue of the dentist’s alleged failure to obtain adequate radiographs. Many dentists hold the view that periodic full-mouth radiographs and/or periapical radiographs should be a part of the periodic examination because they facilitate the diagnosis of decay, periodontal disease, existence and position of impacted teeth, and the position of teeth in relation to the inferior alveolar canal and maxillary sinus. In addition, a panoramic radiograph with appropriate distortion markers or other radiographic study is often suggested as a diagnostic tool before any implant Chapter 4 51 Dental Risk Management placement. The adequacy of radiographic examination is frequently raised as an issue in failure to diagnose oral cancer claims. Failure to Refer When a general dentist treats a condition that falls within a specialty area of treatment, the general dentist is held to the same standard of care as the specialist. Therefore, the general dentist who undertakes treatment that falls within any of the specialty areas must render the same quality of care as would be rendered by a specialist. If the general dentist has any doubts about his or her ability to perform at that level, the patient should be referred to a specialist. Similarly, the general dentist needs to be aware of conditions requiring attention by a specialist and needs to make timely referrals. All referrals should be documented. Any failure on the part of the patient to comply with a referral should also be documented. Occasionally, a health maintenance organization (HMO) or other third party responsible for the payment of the patient’s invoice will place limitations on the dentist’s ability to refer. The practitioner should be aware that these limitations do not in any way lower the standard of care. In short, if it is appropriate to refer a patient for specialized care, the obligation to refer the patient is not altered as a result of limitations placed on the dentist. In situations involving a “close call” on whether to refer a patient to a specialist, the practitioner may want to discuss the option at some length with the patient and document that discussion. Abandonment In some instances the treating dentist will decide to terminate the dentist-patient relationship. Reasons may include the failure on the part of the patient to meet financial responsibilities, behavior on the part of the patient that makes treatment difficult or that is disruptive to the office staff, or perhaps because the dentist is closing or relocating the practice. However, the dentist’s ability to terminate the relationship is limited by the dentist’s corresponding obligation to not place the patient’s health in jeopardy. In addition to a cause of action for medical negligence, courts have recognized the cause of action for abandonment. In the context of the dentist-patient relationship, abandonment has been defined as the unilateral termination by the dentist of the relationship between the dentist and patient without reasonable notice to the patient at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing attention. Thus, courts have recognized that whenever a dentist ends the dentist-patient relationship, the dentist must take steps to ensure that the patient has sufficient time to make arrangements for care and treatment with another dentist, or alternatively, that the dentist addresses any health issues before terminating the relationship. The particular steps that a dentist must take when terminating a patient from the practice varies depending upon the patient’s needs. It is not uncommon for dental patients to fail to meet their financial obligations associated with dental care and treatment. Unfortunately, in situations where a dentist begins treatment and the patient thereafter is unable or unwilling to pay for the cost of services provided, the dentist may not simply refuse to complete treatment if the failure to complete treatment will jeopardize the patient’s health. For example, when an implant has been placed and the dentist has determined that the dentist-patient relationship must end, the dentist still has an obligation to refer the patient for follow-up treatment to the extent necessary to prevent further complications. The dentist may be required to render this treatment and address unpaid fees later; alternatively, the dentist may be able to facilitate treatment by another practitioner. As another example, once the dentist begins preparing a tooth for a crown or initiates endodontic treatment, the dentist may not refuse to complete treatment simply because the fee has not been paid, because the failure to complete these procedures may place the patient’s health in peril. In short, once a patient’s dental condition is compromised by treatment, the patient must be restored to a point of stability. If the dentist is closing the practice, arrangements should be made to refer the patient to other practitioners, and the dentist should make certain that the patient is aware of all ongoing dental needs and the importance of follow-up. Once payment has been made for a procedure, it is the responsibility of the treating dentist to arrange for the completion of treatment at no further charge to the patient. Once a dentist makes a decision to terminate treatment of a patient, the dentist should give the patient written notice of the decision. Depending on the circumstances, it may be appropriate for the practitioner to send this notice via registered or certified mail to establish independent evidence that the patient in fact received the notice. The reasons for the discontinuance of treatment along with an explanation of the patient’s continuing dental needs should be included in the notice. The patient should be warned about the potential ill effects of failing to follow up. In addition, if the treating dentist is unable to continue seeing the patient during a transition period, arrangements should be made for another dentist to provide coverage. It may be appropriate for the dentist to confer with either a professional liability insurance carrier or lawyer before initiating procedures that will terminate a patient relationship. Professional Liability Insurance Considerations It is strongly recommended that every dentist maintain professional liability insurance coverage. The amount of insurance the dentist should maintain varies based on the nature of the dentist’s practice. In recent years, most policies sold have provided at least $1 million of coverage on a per occurrence basis, although many oral surgeons maintain policies that provide greater coverage. Although it may be impractical or even impossible for a dentist to obtain sufficient coverage to insure against all risk of loss, the existence of a professional liability insurance policy providing modest coverage will afford sufficient protection to most dentists under most circumstances. 52 The practitioner should be aware that there are several different types of policies sold, and these policies may contain different substantive provisions. Most policies are sold on either an occurrence format or claims-made format. An occurrence policy provides coverage to the dentist for incidents occurring between the dates specified in the policy; a claimsmade policy provides coverage to the dentist for claims first made between the dates set forth in the policy. If a dentist purchases a claims-made policy, the dentist should be aware that a “tail” for the policy may be needed when the practitioner elects to retire or change insurance carriers to ensure that claims asserted after the change but arising before the change are covered. Under an occurrence policy, no tail is needed. Professional liability policies may contain a provision that permits practitioners to influence the question of whether settlement discussions will be initiated on their behalf. These provisions are typically referred to as consent clauses. A consent clause essentially prohibits the insurance carrier from initiating settlement discussions without the dentist’s written permission. Other considerations in selecting a professional liability insurance carrier may include the following: (1) the amount of the annual premium, (2) the financial rating of the underwriter, (3) the reputation of the company in the dental community, and (4) the reputation of the attorneys retained by the insurance company for the defense of lawsuits against its insured practitioners. For guidance concerning the selection of a professional liability insurance carrier, insurance agents, colleagues, or personal counsel may be consulted. Frequent Complications Associated With Implant Dentistry As every practitioner knows, implant dentistry involves the risk of complications that can occur even with reasonable care. For purposes of this section, some of the most common complications associated with implant dentistry are identified. Of course, these complications are not necessarily unique to implant dentistry. The practitioner should strongly consider the use of a written informed consent form. These forms identify the potential implant complications along with other complications that are associated with any type of oral surgical procedure. Informed consent forms document that the patient has been informed of the potential risks and thereby minimize the possibility that the practitioner will be subject to a claim premised on a theory of lack of informed consent. Many forms are available from such organizations as the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS),* The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI),† and the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP).‡ *American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons: 9700 West Bryn Mawr Avenue, Rosemont, IL 60018-5701. † The International Congress of Oral Implantologists, 248 Lorraine Avenue, 3rd Floor, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043-1454. ‡ The American Academy of Periodontology, 737 North Michigan, Suite 800, Chicago, Illinois 60611-2690. Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management Implant Failure All dental implants are subject to failure on occasion. Failures may be difficult or impossible to predict; even after a failure, the cause of the failure is often difficult to identify. It is well established that failures occur under the best of care. Therefore, before deciding to proceed with implant therapy the patient should be informed of the risk of complications and the potential of failure along with the likely sequelae of implant failure. Altered Sensation and Nerve Injuries One of the complications of mandibular implant treatment is altered neurologic sensation. Altered sensation is most typically attributable to compression, impingement, or in some cases tearing or severing of the inferior alveolar or mental neurovascular bundle by the implant or instrumentation. Although such an injury may occur with reasonable care, reasonable steps should be taken to assess the amount of available vertical bone above the nerve before placing implants. Bone grafting, where indicated, may be considered to minimize the risk of this complication. It is recommended that the clinician obtain a signed informed consent advising all patients who have elected to undergo implant therapy of the potential for altered sensation. Depending on the nerves involved, the mechanism of injury, and the patient’s physiological response, complaints concerning altered sensation may vary from insignificant to debilitating. Understandably, the patient who was not warned of the possibility of altered sensation secondary to implant reconstruction is more likely to consider a claim for malpractice if the complication arises. A signed document establishing that the patient has been informed of the risk will be most beneficial in the event of a claim. Of course, even the existence of a signed informed consent form will not necessarily preclude a claim from being asserted. Thus it is essential that the practitioner consider treatment alternatives that may reduce the risk and implement reasonable procedures that identify the location of nerves to the extent possible before proceeding with implant placement. These procedures can be aided by radiographic analysis. In severe atrophic cases, the use of computerized tomographic scans with three-dimensional reformatted images may provide additional useful information.9 When the patient experiences the complication of altered sensation, a frank and honest discussion with the patient concerning the nature of the complication is appropriate. Documentation concerning these discussions should be included in the record. Finally, periodic follow-up examinations with reported findings are recommended, especially during the first 6 months after the injury. When repair may be an option, the practitioner should consider further procedures, treatment with available medications, and appropriate referral. Pretreatment planning is of the utmost importance in minimizing the risk of nerve injuries secondary to implant placement. Figure 4-1, A depicts the pretreatment, intraoperative, Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management 53 A Figure 4-2. Panoramic radiograph depicts placement of a mandibular implant to the depth of the inferior alveolar canal. B Figure 4-1. A, Series of three periapical radiographs depict mandibular implant placement close to or in the inferior alveolar canal. B, Computerized tomographic scan illustrates that the implants are in fact impeding the inferior alveolar canal. and posttreatment periapical films involving the placement of two endosseous mandibular implants. In selecting implant lengths, the practitioner used measurement pins intraoperatively. In this particular case, the measurement pins appear to be close to or in the inferior alveolar canal. The third periapical film of the implant placements suggests that the implants were placed to the same depth as the measurement pins. After implant placement, the patient complained of a loss of sensation. A computerized tomographic scan with three-dimensional reformatted images reveals invasion of the inferior alveolar canal by both implants (Figure 4-1, B). In this example, the dentist used an outdated periapical radiographic system with no attempt to determine accurate measurements via radiographic markers. It would appear that the practitioner placed the implants precisely where intended. Unfortunately, the practitioner did not accurately identify the location of the nerve before implant placement. After the practitioner selects an implant of the appropriate dimensions it is appropriate to take steps intraoperatively to ensure that the intended implant is properly placed. Figure 4-2 depicts a situation in which the oral surgeon performed an appropriate pretreatment evaluation and determined that a 13-mm implant could be safely placed with minimal risk of injury to the nerve. Unfortunately, the practitioner was incorrectly handed a 15-mm implant during the procedure and the implant was placed to the depth of the nerve. Fortunately, this situation did not lead to any nerve injury. Although the implant appears to extend to the depth of the nerve, in this case the implant was fortuitously inserted either buccally or lingually to the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle with no resultant neurologic sequelae. Figure 4-3. Panoramic radiograph with anterior implant into inferior alveolar canal and poor alignment. Ball bearing used to ascertain distortion factor of the edentulous area. Figure 4-3 depicts a panoramic radiograph showing the anterior implant placed to the depth of the inferior alveolar canal and in far from ideal alignment. The dentist who performed the procedure reportedly did not take a pretreatment panoramic radiograph, did not perform a diagnostic wax-up for placement or positioning of the implants, and used no surgical guide during the surgery. As a result, the length of the implant based on the vertical height of the bone was miscalculated, leading to permanent and total numbness of the vermilion border of the lip from the midline to the commissure and extending inferiorly to the chin point. The implant dentist also failed to refer the patient to a specialist to evaluate the situation. Injury to the inferior alveolar nerve can occur even in situations in which the nerve is not directly impacted by the drill or the implant itself. Figure 4-4, A depicts a situation in which a core of bone became mobilized and came close to or invaded the inferior alveolar canal, leading to symptoms of paresthesia. Fortunately, the patient’s paresthesia resolved over time and the bone core consolidated into the body of the mandible (Figure 4-4, B). 54 Chapter 4 A Dental Risk Management B Figure 4-4. A, Immediate postop radiograph with bone core visible at apical area. B, Six-month postop radiograph with complete resolution of symptoms. A B Figure 4-5. Panoramic radiograph (A) and clinical photograph (B) depict extraoral infection secondary to the placement of a transmandibular implant. Infection and Bone Loss Postoperative infection is a risk of all invasive surgeries, including the placement of dental implants. However, the failure of the implant dentist to eliminate infection prior to the placement of implants may create an increased risk that the implants will subsequently fail due to infection. In a case in which transmandibular implant (TMI) reconstruction was performed, the bone was initially infected, which progressed to chronic infection that ultimately dissected extraorally (Figure 4-5). Unchecked, infection will lead to multiple complications beyond implant failure. In another example, a patient with infected teeth in the right mandible had the teeth removed and replaced with two implants while receiving only one preoperative dose of antibiotics to prophylactically cover him due to a total knee replacement. Unfortunately, the one prophylactic preoperative dose of antibiotics did not resolve his preexisting infection, which resulted in a continuous infection in the mandible. A subsequent referral to an infectious diseases specialist for daily intravenous antibiotics was insufficient to clear the infection. The implants ultimately needed to be removed and bone grafting was necessary to repair a large defect that developed in the mandible due to the presence of infection. (Figure 4-6, A depicts the preoperative infection associated with tooth #28; Figure 4-6, B demonstrates severe bone loss around the infected implant sites.) In a case involving a fully reconstructed mandible with nine endosseous implants, all nine implants failed because of localized progressive infection (Figure 4-7). In this case, the patient did not want to be edentulous for any significant period. Thus chronic peridontally infected teeth were left in the mandible after the placement of the implants and during the healing period to support a transitional prosthesis. The presence of infection related to the residual natural abutments acted as a “seeding” mechanism during this period, which ultimately involved the tissue surrounding each of the implants. This case demonstrates the need to address all existing pathologic conditions before proceeding with elective implant placement. Implant reconstruction carries with it the risk of postsurgical infection. Because it is not possible to eliminate this risk, the practitioner should document the fact that the patient has Chapter 4 55 Dental Risk Management A B Figure 4-6. A, Preoperative panoramic radiograph. Notice the infection associated with tooth #28. B, Preoperative CT scan demonstrating severe bone loss around the infected implant sites. Figure 4-7. Panoramic radiograph depicts full mandibular reconstruction with widespread infection. been informed of the risk. The practitioner should consider the appropriate course of antibiotic therapy when indicated before, during, and after surgery in an effort to minimize the risk. Postsurgically, the patient should be followed at reasonable intervals to evaluate for the presence of infection and potential bone loss. Maxillary Sinus Complications and Failures Perhaps the most frequent complication associated with the placement of endosseous implants in the maxilla occurs when the implant either penetrates the sinus or loosens and drifts entirely into the sinus. Either of these scenarios may arise with reasonable care. To minimize the risk of these complications, the practitioner should consider available grafting procedures. The available scientific literature concerning the efficacy of alternative procedures is rapidly expanding, and the practitioner must remain up-to-date on the scientific literature. Procedures and materials that were routinely used 5 or 10 years ago have fallen out of favor, whereas newer procedures and materials have gained wide acceptance. In this regard, it should be Figure 4-8. Radiograph depicts maxillary endosseous implant that has become dislodged and has drifted into the sinus. noted that the standard of care is not stagnant. What many practitioners might have considered as the standard of care a few years ago may be widely regarded as substandard today. When an implant merely impinges on the sinus, as with sinus floor elevation procedures, the patient will not typically experience any complications. However, the implant should be monitored periodically to ensure that the implant remains stable. If the implant loosened, it would typically be appropriate for the practitioner to recommend removal of the implant. Should the implant drift entirely into the sinus, an experienced and qualified specialist should surgically remove the displaced implant in the least invasive manner available. An edentulous patient was reconstructed with multiple endosseous implants (Figure 4-8). Eight implants were placed in the maxillary arch in conjunction with sinus augmentation bone grafts. The film clearly revealed that one of the implants drifted into the sinus; in fact, the screw also separated from the implant and positioned itself medially to the implant. This patient experienced no significant complications as a result of the single implant complication and resultant failure, demonstrating the benefits of over-engineering. By placing more implants than required to effect restoration, the practitioner 56 Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management facilitated completion of the case in spite of the loss of one implant.10 To reduce the risk of a failure such as this, the practitioner should consider a grafting procedure. Interestingly, a grafting procedure was performed in this case. Thus the loss of an implant into the sinus is a risk of the procedure, irrespective of the steps taken to minimize the likelihood of this complication. Obviously, the patient must be informed when a complication of this nature occurs. Subperiosteal Implants Subperiosteal implants were widely used in the reconstruction of the mandible and in some cases the maxilla in the 1960s through the early 1990s. However, over time, the subperiosteal implant has fallen out of favor with many practitioners. The single biggest disadvantage of the subperiosteal implant is that it is a single unit. As a result, if the patient experiences a complication involving bone loss, infection, or gingival hypertrophy in any limited area of the maxilla or mandible, the entire prosthesis will typically require removal, although it should be noted that some practitioners have been successful in removing only part of the implant. In comparison, when a lower jaw is constructed using multiple endosseous implants and there is a failure of one of these implants, the patient may be able to continue functioning on the remaining implants and existing prosthesis. Alternatively, the patient will require a far less invasive procedure to replace a single endosseous implant than would be required to replace a subperiosteal implant. Common complications associated with subperiosteal implants include atrophic changes in the jaw, which will cause the implant to become loose and, in turn, cause the entire implant to become less stable, facilitating infection. In addition to atrophic changes, a patient may experience an area of localized infection around one of the implant posts, which may extend into the supporting bone with the same result. Figure 4-9 shows a subperiosteal implant that is destined for failure because of an inappropriate implant design, sitting on top of the bony ridge with minimal contact between the framework for the implant and existing bone. The implant should be designed in such a way that the framework wraps around the bone to facilitate stability and spread the forces of occlusion more evenly throughout the existing bone. A fracture of the subperiosteal implant along with bone loss secondary to chronic infection left unchecked may lead to the loss of all bony support and the need for partial or complete jaw reconstructive surgery (Figure 4-10). This situation illustrates the need for periodic evaluation of the implant patient to diagnose infection and, if appropriate, remove the implant before extensive damage occurs. Subperiosteal implants in the maxilla have been shown to have only an approximately 50% 5-year survival rate. A maxillary subperiosteal implant that was used to support a fixed cementable cast prosthesis was later found to have resorbed both into the floor of the nose and maxillary sinus (Figure 4-11). The subperiosteal implant was lost due to chronic infection. Removal of the subperiosteal implant was Figure 4-9. Panoramic radiograph demonstrates subperiosteal implant with inadequate contact between framework and bone. Figure 4-10. Panoramic radiograph showing a fractured subperiosteal implant. Figure 4-11. Preoperative panoramic radiograph showing a maxillary subperiosteal implant that has resorbed into both the floor of the nose and maxillary sinus. accomplished only with great difficulty because the framework had resorbed both into the floor of the nose and maxillary sinus. Extensive grafting, performed in stages, was necessary to restore the area for the later placement of a series of endosteal implants. Chapter 4 57 Dental Risk Management Transmandibular Implants A significant amount of research has been conducted on TMIs and Smooth Staple Implants, and their use is being advocated by some practitioners.11 The theoretical advantage of this implant system is that the implant itself, rather than the jaw bone, absorbs the trauma of daily function. For the severely atrophic jaw, the transmandibular design may be an appropriate solution. However, some practitioners believe that the staple will ultimately prove to have a higher failure rate than alternative procedures. In addition, some practitioners believe that these devices increase the risk of a jaw fracture over alternatives; there is no conclusive scientific literature on the subject. Aesthetic Considerations and Prosthesis A poorly designed crown placed over an endosseous implant does not extend to the gingival margin or fully cover the implant appliance (Figure 4-12). The restorative dentist’s failure to provide an adequately designed crown may lead to poor daily maintenance with subsequent localized infection, giving rise to potential implant failure, as well as unacceptable aesthetic results. Ideally, during the treatment planning stage, the team members should consult each other to determine whether the patient will be restored with a fixed or removable prosthesis. The patient should be involved in the decision-making process and should understand the options and treatment plan as developed before treatment is initiated. Often it is difficult to predict with certainty whether a patient can be restored with a fixed prosthesis; where there is any uncertainty, the patient who is seeking a fixed prosthesis should be advised ahead of time that a removable prosthesis may be required. Considerations in the decision to restore the patient with a fixed or removable prosthesis include the patient’s age, overall health, oral hygiene capabilities, jaw relationships, and degree of atrophy. A patient who is impaired by vision difficulties or arthritis may require a removable prosthesis to ensure more Figure 4-12. Inadequate restoration over implant. optimal hygiene performance to minimize the risk of infection. Figure 4-13 illustrates an implant design flaw. In this case, the dentist placed implants in the anterior mandible with the expectation that a cantilever attachment to the implant bar would aid in the support of the prosthesis in the posterior. The excessive length of the cantilevered portion of the connector bar caused excessive torque on the distal-most implants, creating bone loss and soft tissue complications. Figure 4-14 depicts an implant that failed due to the restoring dentist’s failure to place an abutment in the implant. Only an occlusal fastening screw was present. The case illustrates that an implant properly placed by an implant dentist can subsequently fail due to the improper actions of the restoring dentist. Implant Fractures Endosseous implants are also susceptible to fracture. Figure 4-15 depicts a situation in which the practitioner placed two endosseous implants, and the restorative dentist then placed a cantilever abutment distal to the implants. Over time, the torque caused by functional load caused micromovement, leading to the loosening of the fastening screw in the distal implant and the fracture of that implant. Absent the cantilever design, it is unlikely that the implant would have fractured. Endosseous implants can also fracture due to the failure of the implant dentist to prepare the receptor site to the appropriate depth. Figure 4-16 depicts a maxillary implant with a collar that fractured and separated from the body of the implant when the implant dentist used excessive pressure in attempting to “muscle” the implant into position in a situation in which the receptor site was not prepared to an appropriate depth. Unfortunately, the fractured implant could not be conventionally removed because there were no wrenches or tools that could be inserted internally, and thus a surgical procedure involving the need to remove bone was used. The patient subsequently required extensive bone grafting to repair Figure 4-13. Implant design deficiency in which excessive torque would be applied to distal implants because of the excessive length of the cantilevered bar. 58 Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management A A B Figure 4-16. A, Panoramic radiograph of fractured left maxillary implant. B, Clinical view of fractured implant. B Figure 4-14. A, Postimplant failure without abutment. B, Occlusal view of explanted implant with fastening screw only and no abutment. Figure 4-15. Periapical radiograph showing implant fracture secondary to excessive torque. the resulting defect caused by the removal of the fractured implant. Conclusion Today’s society is the most litigious in the history of humankind. The public is bombarded with media reports of malprac- tice verdicts and huge settlements along with billboards, radio spots, and television commercials from attorneys promising substantial compensation at little or no risk to the dissatisfied patient. Plaintiff attorneys have developed extremely sophisticated techniques and strategies for recovering money on behalf of their clients, even when the underlying claim appears defensible. Because of these factors, it is essential that the clinician be familiar with risk management practices. All too often, an otherwise defensible claim becomes extremely difficult to defend by virtue of an inappropriate comment to the patient, an inappropriate entry in the records, a seemingly innocent correction of the records, or other inappropriate communications. Every clinician should attend risk management seminars and make an effort to familiarize staff with sound risk management practices. When potential risk management issues arise, it is appropriate for the clinician to consult with a professional liability insurance carrier and an attorney knowledgeable in the defense of malpractice claims. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. REFERENCES 1. Shulman JD, Sutherland JN: Reports to the National Practitioner Data Bank involving dentists, 1990–2004, J Am Dent Assoc 137(4):523-528, 2006. 2. American Dental Association: Dental Professional Liability: 2005 Survey conducted by the ADA Council on members insurance and retirement programs. www.ada.org/prof/prac/insure/liability/index.asp. 2005. 3. Sloin C, DMD: Personal communications, unpublished study, 2000. 4. Jaeger G: Personal communications, unpublished study, 2007. Chapter 4 Dental Risk Management 5. National Practitioner Data Bank: 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration, p. 62. www.npdb-hipdb. hrsa.gov/pubs/stats/2004_NPDB_Annual_Report.pdf, 2004. 6. National Practitioner Data Bank: 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration, p. 29. www.npdb-hipdb. hrsa.gov/pubs/stats/2004_NPDB_Annual_Report.pdf, 2004. 7. National Practitioner Data Bank: 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration, pp. 29-30, 69. www. npdb-hipdb.hrsa.gov/pubs/stats/2004_NPDB_Annual_Report.pdf, 2004. 59 8. National Practitioner Data Bank: 2004 Annual Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration, p. 71. www.npdb-hipdb. hrsa.gov/pubs/stats/2004_NPDB_Annual_Report.pdf, 2004. 9. Morgan CL: Basic principles of computed tomography, Baltimore, 1983, University Park Press. 10. The American Academy of Osseointegration, Sinus Consensus Conference, November, 1996. 11. Powers MP, Bosker H: The transmandibular reconstruction system. reconstructive preprosthetic oral and maxillofacial surgery, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders. Charles A. Babbush Joel L. Rosenlicht C H A P T E R 5 MASTER PLANNING OF THE IMPLANT CASE Over the past three decades implant dentistry has become the leading and most dynamic discipline in the dental field. Oral reconstruction with dental implants has gone from just singletooth replacements and over-dentures to encompass sophisticated surgical and prosthetic techniques and principles. Every specialty within dentistry plays an important part in the successful outcomes of these very rewarding cases. This chapter describes the interdisciplinary approach to comprehensive treatment planning and the many facets involved in quality, long-standing aesthetic and functional treatment.1,2 Initial Consultation The initial consultation, or at least an appointment to expose the patient to implant or other oral reconstruction, can be initiated by a variety of dental practitioners. An orthodontist may evaluate a patient with congenitally missing teeth. An endodontist may determine that a tooth is fractured and is not suitable for endodontics. A periodontist may feel that progressive, uncontrolled or refractory periodontal disease may not benefit from further traditional treatment. An oral surgeon might prepare teeth being extracted for ridge preservation or determine that ridge augmentation will provide optimal support for dental implants. Most often, though, the general dentist, or prosthodontist, sees a patient with reconstructive needs and makes the appropriate initial consultation for treatment. In the initial consultation the patient’s medical and dental status can be identified and evaluated. If implant therapy is an 60 appropriate option, then a preliminary treatment plan can be developed. The patient’s health status should be evaluated in a way similar to the screening admissions procedure conducted with patients entering the hospital.3-5 The main components to be considered are: 1. The chief complaint 2. The history of the present illness 3. The medical history 4. The dental status Chief Complaint The chief complaint may range from “I don’t like how I look” to “I have worn dentures for 37 years, and I can no longer function with them.” The focus in evaluation of the patient’s chief complaint is whatever factors prompted the person to seek rehabilitation at this time. Sometimes the discussion will reveal concerns beyond those the patient first mentions. For example, patients may say that their dentures no longer function well, but subsequently, they may describe pain during mastication. This additional information can be an important diagnostic aid. If patients cite cosmetic concerns, these must be placed in context. Implant dentistry often cannot match the needs, wants, or desires of the person whose primary goal is to look fundamentally different. However, if functional concerns are the primary goals and cosmetic concerns are secondary, implant dentistry usually can give such patients what they want. Chapter 5 History of Present Illness The next component of interest is the history of the present illness. The practitioner must identify what in the patient’s history produced the present situation, especially in cases in which atrophy in the maxilla or mandible is severely advanced. Did the patient have poor quality care? Did the patient decline to seek any care at all? Did the patient lose teeth prematurely and not have the appropriate dietary intake to sustain good levels of bone support? Has the patient been edentulous for several decades, and did this extended time lead to severe atrophy? Was the patient involved in a traumatic injury: Did a baseball bat, a thrown ball, a fist or some other object traumatize one of more teeth and cause their demise? Was any pathological lesion or tumor involved in the cause of tooth loss and subsequent bone loss? Medical History In gathering the patient’s medical history, special attention should be given to whether the patient has the ability to physically and emotionally sustain all the procedures that may be required in implant therapy, including surgery, a variety of anesthetics and pain-control drugs, and prosthetic rehabilitation.6-8 The American Dental Association provides a long-form health questionnaire on their website that is an excellent tool for gathering this information, available at https://siebel.ada. org/ecustomer_enu/start.swe?SWECmd=Start.9 Figure 5-1 shows an example of a typical health history questionnaire. In addition to obtaining the patient’s health history, the doctor must assess vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, and respiration) and record these assessments in the patient’s chart. When a patient has not had a comprehensive medical work-up for several years or when findings are positive on the health questionnaire, additional laboratory testing may be advisable. These tests may include complete blood count, urinalysis, or sequential multiple analysis of the blood chemistry (SMAC). BOX 5-1 61 Master Planning of the Implant Case The results can contribute to the patient’s medical profile (Table 5-1).2,3 Combining the information from the health questionnaire, the vital signs, and the laboratory test results will enable the doctor to categorize each patient into one of the five classifications of presurgical risk formulated by the American Society of Anesthesiology (Box 5-1).8 According to this scheme, a Class I category includes the patient who is physiologically normal, has no medical diseases, and lives a normal daily lifestyle. The Class II category includes the patient who has some type of medical disease, but the disorder is controlled with TABLE 5-1 Complete metabolic panel Test procedure Units Sodium Potassium Chloride Carbon dioxide Calcium Alkaline phosphate AST ALT Bilirubin, total Glucose Urea nitrogen Creatinine BUN/creatinine ratio Protein, total Albumin Globulin, calculated A/G ratio Egfr non-African American Egfr African American mmol/L mmol/L mmol/L mmol/L mg/dL Units/L Units/L Units/L mg/dL mg/dL mg/dL mg/dL Reference range 135-146 3.5-5.3 98-110 21-33 8.6-10.2 33-130 10-35 6-40 0.2-1.2 65-99 7-25 0.60-1.18 6-22 g/dL 6.2-8.3 g/dL 3.6-5.1 g/dL 2.2-3.9 1.0-2.1 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 > or = 60 mL/min/ 1/73 m2 > or = 60 The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification of presurgical risk Patients who manifest systemic disease that interferes with their normal daily living pattern (e.g., inhibits their employment, restricts their social activity, or otherwise does not allow them to function physically and mentally in a normal or almost normal manner) should not be considered as candidates for an elective procedure such as oral implant reconstruction (R,R). Classifying patients according to the following numerical ratings as established by the American Society of Anesthesiology is helpful in the selection process (R): Class I: A patient who has no organic disease or in whom the disease is localized and causes no systemic disturbances. Class II: A patient exhibiting slight to moderate systemic disturbance which may or may not be associated with the surgical complaint and which interferes only moderately with the patient’s normal activities and general physiologic equilibrium. Class III: A patient exhibiting severe systemic disturbance which may or may not be associated with the surgical complaint and which seriously interferes with the patient’s normal activity. Class IV: A patient exhibiting extreme systemic disturbance which may or may not be associated with the surgical complaint, which interferes seriously with the patient’s normal activities, and which has already become a threat to life. Class V: The rare person who is moribund before operating, whose preoperative condition is such that the patient is expected to die within 24 hours even if not subjected to the additional strain of surgery. Class VI: A patient who is considered brain dead and is a potential organ donor. 62 Chapter 5 Master Planning of the Implant Case HEALTH QUESTIONNAIRE Patient’s Name:_______________________________________ Date:___________________________ I. In the following questions, circle yes or no, whichever applies. Your answers are for our records only and will be considered confidential. 1. 2. 3. Yes Yes Yes No No No 4. 5. Yes Yes No No 6. Yes No Has there been any change in your general health within in past year? My last physical examination was on ______________________ Are you under the care of a physician? _____________________ If so, what is the condition being treated? _________________________ Name and address of physician Have you had any serious illness or operations? If so, what was it? ____________________________________________ Have you been hospitalized or had a serious illness within the past five (5) years? If so, what was the problem? ____________________________________ II. DO YOU HAVE OR HAVE YOU HAD ANY OF THE FOLLOWING DISEASES OR PROBLEMS: 18. Yes Inflammatory rheumatism (painful swollen joints) No 7. Yes Rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease No 19. Yes Stomach ulcers No 8. Yes Congenital heart lesions, mitral valve prolapse No 20. Yes Kidney trouble No 9. Yes Cardiovascular disease (heart trouble, No 21. Tuberculosis No Yes heart attack, coronary insufficiency, 22. Yes Do you have a persistent cough or cough up blood? No coronary occlusion, high blood pressure, 23. Yes Low blood pressure No arteriosclerosis, stroke 24. Yes Venereal disease/herpes/AIDS No 10. Yes Allergies No 25. Yes Other No 11. Yes Sinus trouble No 26. Yes Have you had abnormal bleeding associated with No 12. Yes Asthma or hay fever No previous extractions, surgery, trauma? 13. Yes Hives or skin rash No Do you bruise easily? No 14. Yes Yes Fainting spells or seizures No Have you ever had a blood transfusion? No 15. Yes Yes Diabetes No If so, explain_______________________________ Do you urinate (pass water) more than six times No Yes 27. Yes Do you have any blood disorders, such as anemia? No a day? 28. Yes Have you had surgery or x-ray treatment for tumor, No Are you thirsty much of the time? No Yes growth, or other conditions of your mouth or lips? Does your mouth frequently become dry? No Yes 29. Yes Are you taking any drying medicines? No 16. Yes Hepatitis, jaundice, or liver disease No If so, what _________________________________ 17. Yes Arthritis No III. ARE YOU TAKING ANY OF THE FOLLOWING: 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Aspirin Insulin, tolbutamide (Orinase) or similar drug Digitalis, or drugs for heart trouble Nitroglycerin Other Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes No Do you have any disease, condition, or problem not listed that you think I should know about? Are you employed in any situation that exposes you regularly to x-rays or other ionizing radiation? Are you wearing contact lenses? Do you smoke cigarettes, cigars, pipe, or chew tobacco? How many each day?________ Do you use recreational drugs? 56. Yes No Do you have any problems with your menstrual period? 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. Antibiotics or sulfa drugs Anticoagulants (blood thinners) Medicine for high blood pressure Cortisone (steroids) Tranquilizers Antihistamines IV. ARE YOU ALLERGIC OR HAVE YOU REACTED ADVERSELY TO: 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No No No No No V. WOMEN: 55. Yes No 50. Local anesthetics Penicillin or other antibiotics 51. Sulfa drugs Barbiturates, sedatives or sleeping pills 52. Aspirin 53. Iodine Codeine or other narcotics 54. Other Have you had any serious trouble associated with any previous dental treatment? If so, explain ________________________________ Are you pregnant? Signature of Patient ___________________________________________ Doctor’s Signature ____________________________________________ Figure 5-1. Health history questionnaire. medications. The patient can thus engage in normal daily activity. An example of this category of patient is one with hypertension who has been placed on antihypertensive medication and, as a result, has normal blood pressure and no other impairments. The Class III category includes the patient who has multiple medical problems, such as advanced-stage hypertensive cardiovascular disease or insulin-dependent diabetes, with impaired normal activity. Patients in the Class IV and V categories have advanced states of disease. Class VI is a patient who is considered brain dead and is a potential organ donor. For example, a patient in the Class IV category has a serious medical condition requiring immediate attention, such as the person with acute gallbladder disease who needs immediate treatment. The patient in the Class V category is usually moribund and will not survive the next 24 hours. Most patients who seek implant reconstruction fall into the Class I or II categories and sometimes Class III. For obvious reasons, patients in Classes IV and V are not appropriate candidates for implant procedures. However, consideration of whether a patient falls into Class I, II, or III will enable the implant practitioner to more effectively decide what kinds of procedures should be undertaken, where the surgery should be performed, and what kind of anesthesia is appropriate. Furthermore, cases with patients categorized as Class III may Chapter 5 63 Master Planning of the Implant Case require preparatory measures such as stabilizing or controlling a diabetic patient before implant surgery can be considered. Dental Status It is essential to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s dental, as well as medical, status. In addition to questioning patients about their dental history, a thorough examination should be conducted. An evaluation of the hard and soft tissues of the entire maxillofacial skeleton should be included and appropriate radiographic studies must be obtained. Today’s modern dental offices can provide a host of radiographic information through digital and computer analog equipment that allows unprecedented detail and data applications never available before. Digital panoramic and officebased cone beam CT scanners (Figure 5-2) are now readily available. These devices can give studies that accurately define the full scope of the maxilla and mandible, as well as the accompanying vital structures (i.e., sinus, floor of the nose, position of the mandibular canal, mental foramen) (Figure 5-3). In addition, information about the thickness of cortical plates, bone densities, and soft tissue contours is easily obtained. Chapter 8, Contemporary Radiographic Evaluation of the Implant Candidate, and Chapter 18, An Introduction to Guided Surgery, expand on this technology. There still is a place for conventional film-based radiographs because much valuable information can be learned from them. These might include occlusal films, lateral cephalometric images, and periapical or panoramic images (Figure 5-4).10 However, with the advent of digital referenced planning software our ability to diagnose and plan procedures virtually takes radiographic diagnosis and treatment planning to a new level (Figures 5-5 and 5-6). In addition to gathering the dental history, a thorough clinical exam should include the patient’s teeth, soft tissue, and hard tissue. Mounted casts also should be obtained, and become an important component of the patient’s treatment plan (Figure 5-7). The patient’s facial appearance also should be documented with preoperative extraoral and intraoral photographs (Figure A 5-8). In addition to acting as risk management tools, these preoperative documents usually serve as references for all members of the implant team during detailed case planning. Nontangible considerations also deserve attention. The patient’s needs, wants, desires, and psychosocial conditions should be ascertained and recorded. Issues of self-confidence and self-esteem should also be reviewed (Figure 5-9). Figure 5-2. I-CAT cone beam CT scanner installed in a dental office environment. B Figure 5-3. A, Panoramic radiograph demonstrating severe advanced maxillary and mandibular atrophy. B, Panoramic radiograph demonstrating the maxillary sinus cavities, nasal anatomy, defined inferior alveolar canals, and mental foramen. 64 Chapter 5 Master Planning of the Implant Case A C D B Figure 5-4. A, Conventional occlusal radiograph. B, Conventional lateral cephalometric radiograph. C, Conventional periapical radiograph. D, Conventional panoramic radiograph. Patient Education A B Figure 5-5. CT scan 3-D SimPlant surgical planning software program demonstrates a well-planned implant reconstruction in both the maxilla (A) and mandible (B). In addition to providing the practitioner with crucial information concerning the patient’s needs and wants, the initial consultation also should serve to educate and orient the patient. Various visual aids can assist with this task, including models representing completed forms of single-tooth, multiple-tooth, and full-arch reconstruction (Figure 5-10). Photographs also can communicate to the patient the potential appearance of the final reconstruction in the oral cavity (Figure 5-11). Videotapes and DVDs, available from most commercial companies that sell implants, can demonstrate various implant procedures and provide a general overview. All of these presentation aids should be noted in the patient’s chart as riskmanagement tools. Printed literature can serve multiple purposes. Brochures that introduce implants and explain how they work can be sent to patients who inquire about implant reconstruction. Patients going through an implant consultation should be given a portfolio of literature to take home. This information will enable them to better communicate with friends and relatives about the process of implant reconstruction. Printed literature also can serve as an educational tool if public education lectures are part of the doctor’s practice domain (Figure 5-12). Figure 5-6. A cone beam CT scan demonstrating a panoramic view (top) and cross-sectional views (bottom) of an intended implant placement. A B Figure 5-7. A, A study cast mounted in a semiadjustable articulator for the replacement of two bicuspid maxillary teeth. B, A study cast mounted in a semiadjustable articulator for the reconstruction of an endentulous maxilla. 66 Chapter 5 Master Planning of the Implant Case A B C C D Figure 5-8. This series of facial photographs demonstrates the need to obtain pretreatment facial documentation (A and B; E and F) so that a valid comparison can be made with the final postsurgical/prosthetic results (C and D; G and H). (From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, The Dental Implant Center Press, 2004.)