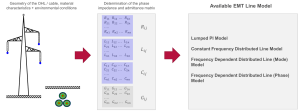

Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Lesson 2.1: Transmission Lines 2.1.2: Electromagnetic Waves → There are two kinds of waves: Lesson 2.1.1: Definition of Transmission Lines Lesson 2.1.2: Electromagnetic Waves Lesson 2.1.3: Types of Transmission Lines Lesson 2.1.4: Transmission Line Characteristics Lesson 2.1.5: Wave Propagation on a Metallic Transmission Line Lesson 2.1.6: Transmission Line Losses 1. 2. Longitudinal – the displacement (amplitude) is in the direction of propagation. Transverse – the direction of displacement is perpendicular to the direction of propagation. 2.1.1: Definition of Transmission Line (TL) Figure 1: Illustration of Longitudinal Wave (LEFT) & Transverse Wave (RIGHT). → It is a metallic conductor system used to transfer electrical energy from one point to another using electrical current flow. It is two wire or more electrical conductors separated by a nonconductive insulator (dielectric), such as a pair of wires of a system of wire pairs. → Propagation of electrical power along a TL occurs in the form of transverse electromagnetic (TEM) waves. → Transmission Lines can be used to propagate DC or low frequency AC (such as 60 cycle electrical power and audio signals) or to propagate VHF (such as microwave radiofrequency signals). → A TEM wave propagates primarily in the nonconductor (dielectric) that separates the 2 conductors of the TL. Therefore, a wave travels or propagates itself through a medium. → Transmission Lines in communication carry telephone signals, computer data in LANs, TV and Internet signals in cable TV systems, and signals from a transmitter to an antenna or from an antenna to a receiver. → In conductors, I and V are accompanied by an electrical field (E) and magnetic field (H) in the adjoining region of space. → Transmission Lines are also short cables connecting equipment or printed circuit board copper traces that connect an embedded microcomputer to other circuits by way of various interfaces. → Transmission Lines are critical links in any communication system. They are more than pieces of wire or cable. Their electrical characteristics are critical and must be matched to the equipment for successful communication to take place. Primary Characteristics of Electromagnetic Waves → Transmission Lines are also circuits. At very high frequencies where wavelengths are short, transmission lines act as resonant circuits and reactive components. Wave Velocity – varies depending on the medium. 1. 𝑐 = 186,000 → At VHF, UHF, and microwave frequencies, most tuned circuits and filters are implemented with transmission lines. 2. 3. A. B. Block diagram of a conventional remotely tuned transmission line (I) circuit. Block diagram of a partially matched, remotely tuned transmission line (I) circuit. 1 Frequency 𝑐/𝜆 Wavelength 𝑚𝑖 𝑚 𝑜𝑟 3 × 108 𝑠 𝑠 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design 2.1.3: Types of Transmission Lines Baluns → The types of transmission lines include: 1. 2. → A circuit device (special transformers) used to connect a balanced transmission line to an unbalanced load. Parallel Wire / Unbalanced / Differential Coaxial / Unbalanced / Single-ended Parallel Wire / Unbalanced / Differential → Made up of 2 parallel conductors spaced from one another by a distance of ½ inch up to several inches. → Both conductors carry current; one conductor carries the signal and the other is the return path. Parallel Conductor Transmission Lines 1. Open-wire Transmission Line: → Metallic Circuit Currents: - → Longitudinal Currents: - - It consists of two parallel wires, spaced between 2 inches to 6 inches and separated by air. - Disadvantage: radiation lines losses are high, and it is susceptible to noise pickup. Currents that flow in opposite directions. Currents that flow in the same directions. 2. 3. Twin-lead / Ribbon Cable: - The spacers between the 2 conductors are replaced with a continuous solid dielectric. - Typical distance between the 2 conductors is 5/16 inch for TV transmission cable. Twisted-pair Cable: Coaxial / Unbalanced / Single-ended → Consists of a solid center conductor surrounded by a plastic insulator (Teflon). Over the insulator is a second conductor, a tubular braid or shield made of fine wires. Formed by twisting together two insulated conductors. - It uses two insulated solid copper wires covered with insulation and loosely twisted together. → One wire is at ground potential, the other wire is at signal potential. - Two types of twisted-pair cable are: o o 4. 2 Unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) cable Shielded twisted-pair (STP) cable Shielded Cable Pair: - To reduce radiation losses and interference, the cable is enclosed in a conductive metal braid. The braid is connected to the ground and acts as a shield. - It also prevents signals from radiating beyond its boundaries and keeps electromagnetic interference from reaching the signal conductors. Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design 2.1.4: Transmission Line Characteristics Concentric or Coaxial Transmission Lines 1. - 2. → The transmission characteristics of a transmission line are called secondary constants and are determined from the four primary constants. Rigid Air Coaxial Cable: The center conductor is surrounded coaxially by a tubular outer conductor and the insulating material is air. Primary Constants 1. 2. 3. 4. Spacer: pyrex, polystyrene, etc. Solid Flexible Coaxial Cable: - The outer conductor is braided, flexible, and coaxial to the center conductor. - Insulating material: solid nonconductive polyethylene material. Resistance Conductance Inductance Capacitance Primary Constants (Parallel Line) → Inductance, L , (H/m): - 𝐿= Inner conductor: flexible copper wire (solid or hollow). 𝜇 𝑠 ln 𝜋 𝑟 Where: µ = 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 μ = μr × 𝜇𝑜 𝜇𝑜 = 4𝜋 × 10−7 𝐻/𝑚 𝜇𝑜 = 1.257 × 10−6 𝐻/𝑚 RG Numbering System → The RG Numbering System of coaxial cable refers to the fact that the RF (Radio Frequency) signal is guided down the center conductor of the cable system. → Capacitance, C , (F/m): → The RG Numbering System dates back to WWII United States Military specifications and has no real contemporary significance other than type conductors. 𝐶= 𝜋𝜖 𝑠 ln 𝑟 Where: → Each RG number does, however, specify impedance, core conductor gauge (AWG) and type, outside diameter (OD), and other physical attributes of the cable. 𝜖 = 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝜖 = 𝜖𝑅 × 𝜖𝑂 𝜖𝑂 = 8.854 × 10−12 𝐹/𝑚 → Resistance, R , (Ω/m): 𝑅= 1 𝜋𝑟𝛿𝛿𝑐 Where: 𝛿 = 𝑠𝑘𝑖𝑛 𝑑𝑒𝑝𝑡ℎ 𝛿𝑐 = 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑒𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑐 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 → Conductance, G, (s/m): 𝐺= 𝜋𝜎 cosh−1 𝑠 2𝑟 Where: 𝜎 = 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑑𝑖𝑒𝑙𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐 3 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Primary Constants (Coaxial Line) Secondary Constants → Inductance, L , (H/m): 1. 2. 𝐿= Characteristic Impedance (Zo) Propagation constant 𝜇 Characteristic Impedance (Zo) 𝑏 𝜋 (ln ) 𝑎 → It is a complex quantity that is expressed in ohms (Ω), and is ideally independent of line length and cannot be directly measured Where: 𝑎 = 𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑖𝑢𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑛𝑛𝑒𝑟 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 𝑏 = 𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑖𝑢𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 → Sometimes it is called surge impedance. → The impedance seen looking into an infinitely long line or the impedance seen looking into finite length of line that is terminated in a purely resistive load with a resistance equal to the characteristic impedance of the line. → Capacitance, C , (F/m): 𝐶= 2𝜋𝜖 𝑏 ln 𝑎 Where: 𝑍𝑜 = √ 𝜖 = 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝜖 = 𝜖𝑅 × 𝜖𝑂 𝜖𝑂 = 8.854 × 10−12 𝐹/𝑚 𝑅+𝑗𝜔𝐿 𝐺+𝑗𝜔𝐶 𝑅 𝑍𝑜 = √ ; For ELF, the resistance dominates 𝐺 → Resistance, R , (Ω/m): 𝑍𝑜 = √ 1 𝑅= 1 1 2𝜋𝛿𝛿𝑐 ( + ) 𝑎 𝑏 𝐿 = √ ; For EHF, inductance and capacitance dominate 𝐶 Characteristic Impedance (Zo) for Parallel Line Where: 𝑍𝑜 = 𝛿 = 𝑠𝑘𝑖𝑛 𝑑𝑒𝑝𝑡ℎ 𝛿𝑐 = 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑒𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑐 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 𝑍𝑜 = → Conductance, G, (s/m): 𝑍𝑜 = 𝐺= 𝑗𝜔𝐿 𝑗𝜔𝐶 2𝜋𝜎 𝑏 ln 𝑎 276 √𝑘 276 √𝑘 120 √𝑘 log log 2𝑠 𝑑 𝑠 𝑟 𝑠 ln ; 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑛 𝑑1 ≠ 𝑑2 , then 𝑑 = √𝑑1 × 𝑑2 𝑟 → Dielectric Constant (𝑘 𝑜𝑟 𝜖𝑟 ): Where: 𝜎 = 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑑𝑖𝑒𝑙𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐 4 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Sample Problems involving Characteristic Impedance (Zo) for Parallel Line 1. Determine the Zo for an air dielectric two-wire parallel TL with a D/r ratio of 12.22 Solution: 𝑍𝑜 = 276 log(12.22) 𝒁𝒐 = 𝟑𝟎𝟎 Ω 2. What is the minimum Zo of an air dielectric two-wire line? Solution: 𝑍𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑛 = 𝑍𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑛 = 276 √𝑘 log 276 √1.0006 2𝑠 𝑑 log 2𝑠 𝑑 𝒁𝒐𝒎𝒊𝒏 = 𝟖𝟑 Ω Characteristic Impedance (Zo) for Coaxial Line 𝑍𝑜 = 𝑍𝑜 = 138 √𝑘 60 √𝑘 log ln 𝐷 𝑑 𝐷 𝑟 Where: d = diameter of the inner conductor h = thickness of the outer conductor D = inside diameter of the outer conductor Do = outside diameter of the outer conductor Sample Problems involving Characteristic Impedance (Zo) for Coaxial Line 1. Determine the Zo for an RG-59A coaxial cable with the following specifications: d = 0.025 in, D = 0.15 in, and k = 2.23. Solution: 𝑍𝑜 = 𝑍𝑜 = 138 √𝑘 138 √2.23 log log 𝐷 𝑑 0.15 0.025 𝒁𝒐 𝑚𝑖𝑛 = 𝟕𝟏. 𝟗 Ω 5 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design 2. A 50-ohm coax cable is 150 ft long. It has air dielectric and operates at a frequency of 100 MHz. If the thickness of the outer conductor is 0.005 in and the ‘d’ is 0.162 in, what is the outside diameter of the conductor? Solution: 𝑍𝑜 = 50 = 138 √𝑘 log 𝐷 𝑑 log 𝐷 0.162 138 √1.0006 𝑫 = 𝟎. 𝟑𝟕𝟑 𝒊𝒏 𝐷𝑜 = 𝐷 + 2ℎ 𝐷𝑜 = 0.373 + 2(0.005) 𝑫𝒐 = 𝟎. 𝟑𝟖𝟑 𝒊𝒏 3. A two-wire TL has the following parameters: 𝑅 = 40 Ω/𝑚 𝐶 = 15 𝑛𝐹/𝑚 𝐿 = 5 𝑚𝐻/𝑚 𝐺 = 0.8 𝜇𝑠/𝑚 Find the Zo and the nature of the line at 3 kHz. Solution: 𝑅 + 𝑗𝜔𝐿 𝑍𝑜 = √ 𝐺 + 𝑗𝜔𝐶 → 𝜔 = 2𝜋𝑓 → 𝜔 = 2𝜋𝑓 40 + 𝑗2𝜋(3000)(5 × 10−3 ) 𝑍𝑜 = √ (0.8 × 10−6 ) + 𝑗2𝜋(3000)(15 × 10−9 ) 40 + 𝑗94.2 𝑍𝑜 = √ 0.8 × 10−6 + 2.827 × 10−4 𝒁𝒐 = 𝟔𝟎𝟏. 𝟖𝟐, −𝟏𝟏. 𝟒𝟐°, Ω, 𝑪𝒂𝒑𝒂𝒄𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒗𝒆 Nature of the Transmission Line: Capacitive Purely Capacitive Inductive Purely Inductive (R, -j) (0, -j) (R, +j) (0, +j) 6 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Summary of Transmission Line for Characteristic Impedance Propagation Constant (𝜸) → Sometimes called propagation coefficient. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The input impedance (Zi) of an infinitely long line is resistive and equal to Zo. Electromagnetic waves travel down the line without reflections; such a line is called nonresonant. The ratio of voltage to current at any point along the line is equal to Zo. The incident V and I at any point along the line are in phase. Line losses on a non-resonant line are minimum per unit length. Any transmission line that is terminated in a purely resistive load equal to Zo acts as if it were an infinite line. a. b. c. d. → As the signal propagates down a TL, its amplitude decreases with distance traveled. → Propagation constant determines the reduction in V or I with distance as a TEM wave propagates down a TL. 𝛾 = 𝛼 + 𝑗𝛽 Where: 𝛾 = 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑝𝑎𝑔𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡 (𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕𝒍𝒆𝒔𝒔) 𝛼 = 𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑒𝑓𝑓𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑒𝑛𝑡 (𝒏𝒆𝒑𝒆𝒓𝒔 𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕 𝒍𝒆𝒏𝒈𝒕𝒉) 𝛽 = 𝑝ℎ𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑠ℎ𝑖𝑓𝑡 𝑐𝑜𝑒𝑓𝑓𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑒𝑛𝑡 (𝒓𝒂𝒅𝒊𝒂𝒏𝒔 𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕 𝒍𝒆𝒏𝒈𝒕𝒉) Zi = Zo There is no reflected wave. V and I are in phase. There is a maximum transfer of power from source to load. Characteristic Impedance ✓ → Used to express the attenuation (signal loss) and the phase shift per unit length of a transmission line. A parameter which tells us about the maximum efficiency of a transmission line. 𝛾 = √(𝑅 + 𝑗𝜔𝐿)(𝐺 + 𝑗𝜔𝐶) The propagation constant as a complex quantity Input Impedance ✓ → Because a phase shift of 2π rad occurs over a distance, The actual impedance that has been offered to the current to flow to the load of the transmission line. 𝛽= 2𝜋 360° = 𝜆 𝜆 but 𝜆 = 𝑐 𝑓 𝛽= 2𝜋𝑓 𝑐 At intermediate and radio frequencies, 𝜔𝐿 > 𝑅 and 𝜔𝐶 > 𝐺; thus, ✓ ✓ There is no attenuation to the signal amplitudes and the propagation constant is purely imaginary when the transmission line is ideal. ✓ The impedance seen by any signal entering it. It is caused by the physical dimensions of the transmission line and its downstream circuit elements. 𝛽 = 𝜔√𝐿𝐶 ; use this if LC are given → The current and voltage distribution along a TL is terminated in a load equal to its characteristic impedance (matched line) are determined from the formulas: 𝐼 = 𝐼𝑠 𝑒 −𝑙𝑦 𝑉 = 𝑉𝑠 𝑒 −𝑙𝑦 Where: When the transmission line length is infinite, the input impedance is equal to the characteristic impedance. 𝛾 = 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑝𝑎𝑔𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡 (𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕𝒍𝒆𝒔𝒔) 𝐼𝑠 = 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑡 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 𝑒𝑛𝑑 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑒 (𝒂𝒎𝒑𝒔) 𝑉𝑠 = 𝑣𝑜𝑙𝑡𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑎𝑡 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 𝑒𝑛𝑑 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑒 (𝒗𝒐𝒍𝒕𝒔) 𝑙 = 𝑑𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 𝑎𝑡 𝑤ℎ𝑖𝑐ℎ 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑣𝑜𝑙𝑡𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑑𝑒𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚𝑖𝑛𝑒𝑑 7 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design 2.1.5: Wave Propagation on a Metallic Transmission Line → Velocity Factor: - Sometimes called velocity constant is defined simply as the ratio of actual velocity of propagation of an electromagnetic wave through a given medium to the velocity of propagation through a vacuum (free space). 𝑉𝑓 = 𝑉𝑝 𝐶 When: 𝑉𝑓 = velocity factor 𝑉𝑝 = actual velocity 𝐶 = velocity of propagation through a vacuum (3 x 108 m/s) → Dielectric Constant: - The velocity at which the electromagnetic wave travels through a TL depends on the dielectric constant of the insulating material separating the two conductors. 𝑉𝑓 = 1 √ ∈𝑟 𝑉𝑓 = 1 √𝑘 𝑉𝑝 = 1 √𝐿𝐶 When: ∈𝑟 or k = the dielectric constant or relative permittivity of the material 𝐿 = inductance per unit length (H/m) 𝐶 = capacitance per length (F/m) Material Velocity Factor Vf Vacuum 1.0000 Relative Dielectric Constant ∈𝒓 1.0000 Air 0.9997 1.0006 Teflon foam 0.8200 1.4872 Teflon foam 0.6901 2.100 Polyethylene 0.6637 2.2700 Paper, paraffined 0.6325 2.5000 Polystyrene 0.6325 2.5000 Polyvinyl chloride 0.5505 3.3000 Rubber 0.5774 3.0000 Mica 0.4472 5.0000 Glass 0.3651 7.5000 8 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Sample Problems involving Velocity Factor. 1. For a given length of RG 8 A/U coaxial cable with a distributed capacitance C = 96.6 pF/m, a distributed inductance L = 241.56 nH/m, and a relative dielectric constant of ∈𝑟 = 2.3, determine the velocity of propagation and the velocity factor. Solution: 𝑉𝑝 = 1 1 = = 𝟐. 𝟎𝟕 × 𝟏𝟎𝟖 𝒎/𝒔 √𝐿𝐶 √(96.6×10−12 )(241.56×10−9 ) 2.07×108 𝑚/𝑠 = 𝟎. 𝟔𝟗 3×108 𝑚/𝑠 𝑉 𝑉𝑓 = 𝐶𝑝 = 𝑉𝑓 = 1 √ ∈𝑟 = 1 √2.3 = 𝟎. 𝟔𝟔 2. If the Zo of a TL is 60 ohms and the velocity of signal is 2.4 x 108 m/s, what is the L & C of the line at 1 MHz? Solution: From 𝑉𝑝 = 1 ; √𝐿𝐶 𝐿 √𝐿𝐶 = 1 𝑉𝑝 1 2 𝐿𝐶 = (2.4×108 ) 2 1 8 ) 2.4×10 𝑍𝑜 = √𝐶 3600 𝑐 (𝑐) = ( 𝐿 60 = √𝐶 √(2.4×108 ) 𝐿 1 𝑐= 2 3600 3600 = 𝐶 𝑐 = 6.94 × 10^ − 11 𝐿 = 3600 𝑐 𝒄 = 𝟔𝟗. 𝟒 𝒑𝑭/𝒎 𝐿 = 3600 𝑐 𝐿 = 3600(6.94 × 10−11 ) 𝑳 = 𝟐𝟓𝟎 𝒏𝑯/𝒎 9 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Length of a Transmission Line → Physical Length (S) – also the mechanical length. (unit: m, inch, cm) → Electrical Length (°𝓵) - The length of a TL relative to the length of the wave propagating down it is an important consideration when analyzing TL behavior. At LF (long wavelengths), the voltage along the line remains relatively constant. At HF, several wavelengths of the signal may be present on the line at the same time. The length of a TL is often given in wavelengths rather than linear dimensions. - °ℓ = 𝛽𝑆 But 𝛽 = 2𝜋𝑐 °ℓ = 𝑓 2𝜋𝑓 ×𝑆 𝑐 𝑆 = 𝑝ℎ𝑦𝑠𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑔𝑡ℎ 𝛽 = 𝑝ℎ𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑑𝑒𝑙𝑎𝑦 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑡 Sample Problems involving Electrical Length. 1. What is the length of a half wave coax line at 300 MHz? Solution: ℎ𝑎𝑙𝑓 𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑔𝑡ℎ = 𝑏𝑢𝑡 𝜆 = 𝜆 2 𝑐 𝑓 𝑐 3 × 108 𝜆 𝑓 300 × 1006 = 𝟎. 𝟓 𝒎 = = 2 2 2 2. What is the separation between the space and the load if the operating frequency is 2 MHz and the phase separation is 120°? Solution: °ℓ = 2𝜋𝑓 ×𝑆 𝑐 ℓ 120°(3×108 ) 𝑆 = ° 360°𝑓 = 360°(2×106 ) = 𝟓𝟎 𝒎 10 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Time Delay (td) → Because the velocity of propagation of a TL is less than the velocity of propagation in free space, it is logical to assume that any line will slow down or delay any signal applied to it. → Time delay or transit time is a signal applied at one end of a line that appears sometime later at the other end of the line. → Transmission line delay is often the determining factor in calculating the maximum allowed cable length in LANs. → The amount of delay time is a function of a line’s inductance and capacitance. → The opposition to changes in current offered by the inductance plus the charge and discharge time of the capacitance leads to a finite delay. → The effect of the time delay of a transmission line on signals: (a) Sine wave delay causes lagging phase shift (b) Pulse delay → This delay time is computed with the expression: 𝑡𝑑 = √𝐿𝐶 Where: td = time delay (sec) L = inductance (henry) C = capacitance (farad) → If LC are given per unit length of TL (ft/m), the time delay will also be per unit length (1.5 ns/m). Sample Problems involving Time Delay. a. What is the delay time if the capacitance of a particular line is 30 pF/ft and its inductance is 0.075 µH/ft? Solution: 𝑡𝑑 = √𝐿𝐶 𝑡𝑑 = √(0.075 × 10−6 )(30 × 10−12 ) 𝒕𝒅 = 𝟏. 𝟓 × 𝟏𝟎−𝟗 or 𝟏. 𝟓 𝒏𝒔/𝒇𝒕 b. What is the time delay for a 50 ft length of the same line? Solution: 1.5 × 50 = 𝟕𝟓 𝒏𝒔 𝒐𝒇 𝒅𝒆𝒍𝒂𝒚 11 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Time Delay (td) of a Coaxial Cable → The Time Delay (td) introduced by a coaxial cable can also be calculated by using the formula: 𝑡𝑑 = 1.016√∈𝑟 Where: 𝑡𝑑 = time delay in nanoseconds per foot (ns/ft) ∈𝑟 = dielectric constant → To determine the phase shift represented by the delay, the frequency and period of the sine wave must be known. 1 → The period or time (T) for one cycle can be determined with the well-known formula 𝑡 = , where f is the frequency of the 𝑓 sine wave. Sample Problems involving Time Delay (td) of a Coaxial Cable 1. What is the total delay time introduced by a 75-ft cable with a dielectric constant of 2.3? Solution: 𝑡𝑑 = 1.016√∈𝑟 𝑡𝑑 = 1.016√2.3 𝑡𝑑 = 1.016(1.517) 𝒕𝒅 = 𝟏. 𝟓𝟒 𝒏𝒔/𝒇𝒕 𝑡𝑑 = 1.54(75) 𝒕𝒅 = 𝟏𝟏𝟓. 𝟔 𝒏𝒔 Phase Shift (𝜽) → TL delay is usually ignored in RF applications, and it is virtually irrelevant in radio communication. → However, in HF applications where timing is important, transmission line delay can be significant. → For example, in LANs, the time of transition of the binary pulses on a coaxial cable is often the determining factor in calculating the maximum allowed cable length. 𝜃= 360𝑡𝑑 𝑇 Where: 𝑡𝑑 = time delay in nanoseconds per foot (ns/ft) 𝑇 = period 12 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design Common Transmission Line Characteristics Type of Cable 𝒁𝒐 (Ω) VF, % C, pF/ft Outside diameter, in 𝑽𝒎𝒂𝒙 (rms) Attenuation (dB/100 ft) RG-8/U 52 66 29.5 0.405 4000 2.5 RG-8/U foam 50 80 25.4 0.405 1500 1.6 RG-11/U 75 66 20.6 0.405 4000 2.5 RG-11/U foam 75 80 16.9 0.405 1600 1.6 RG-58A/U 53.5 66 28.5 0.195 1900 2.6 RG-59/U 73 66 21.0 0.242 2300 3.4 RG-62A/U 93 86 13.5 0.242 750 2.8 RG-214/U 50 66 30.8 0.425 5000 2.5 9913 50 84 24.0 0.405 ̶ 1.3 Twin-lead (open line) 300 82 5.8 ̶ ̶ 0.55 * At 100 MHz Sample Problems involving Transmission Line Characteristics 1. A 165-ft section of RG-58A/U at 100 MHz is being used to connect a transmitter to an antenna. Its attenuation for 100 ft at 100 MHz is 5.3 dB. Its input power from a transmitter is 100 W. What are the total attenuation and the output power to the antenna? Solution: Cable Attenuation = 5.3 𝑑𝐵 100𝑓𝑡 = 𝟎. 𝟎𝟓𝟑 𝒅𝑩/𝒇𝒕 Total Attenuation = 0.053 × 165 = 𝟖. 𝟕𝟒𝟓 𝒅𝑩 or − 𝟖. 𝟕𝟒𝟓 𝒅𝑩 𝑑𝐵 = 10 log 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 𝑃𝑖𝑛 = log −1 𝑑𝐵 10 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 𝑃𝑖𝑛 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 = 𝑃𝑖𝑛 (log −1 and 13 𝑑𝐵 10 ) Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design −8.745 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 = 100 log −1 ( ) 10 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 = 100 log −1 (−0.8745) 𝑃𝑜𝑢𝑡 = 100(0.1335) 𝑷𝒐𝒖𝒕 = 𝟏𝟑. 𝟑𝟓 𝑾 2. A 150-ft length of RG-62A/U coaxial cable is used as a transmission line. Find: (a) The load impedance that must be used to terminate the line to avoid reflections. Answer: The characteristic impedance is 93 Ω; therefore, the load must offer a resistance of 93 Ω to avoid reflections. (b) The equivalent inductance per foot. 𝐿 𝑍𝑜 = √ 𝐶 𝑍𝑜 = 93 Ω 𝐶 = 13.5 𝑝𝐹/𝑓𝑡 𝐿 = 𝐶𝑍𝑜2 = (13.5 × 10−12 )(93)2 𝑳 = 𝟏𝟏𝟔. 𝟕𝟔 𝒏𝑯/𝒇𝒕 (c) The time delay introduced by the cable. 𝑡𝑑 = √𝐿𝐶 𝑡𝑑 = √(116.76 × 10−9 )(13.5 × 10−12 ) 𝒕𝒅 = 𝟏. 𝟐𝟓𝟔 𝒏𝒔/𝒇𝒕 𝑡𝑑 = (150 𝑓𝑡)(1.256 𝑛𝑠/𝑓𝑡) 𝒕𝒅 = 𝟏𝟖𝟖. 𝟑 𝒏𝒔 14 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design (d) The phase shift that occurs on a 2.5-MHz sine wave. 1 1 = 𝑓 2.5 × 106 𝑇= 𝑻 = 𝟒𝟎𝟎 𝒏𝒔 𝜃= 𝜃= 360𝑡𝑑 𝑇 (360)(188.3) 400 𝜽 = 𝟏𝟔𝟗. 𝟒𝟕° (e) The total attenuation in decibels. (Refer to the Table of Common TL Characteristics) 𝐴𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 = 2.8 𝑑𝐵 100 𝑓𝑡 𝑨𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒏𝒖𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏 = 𝟎. 𝟎𝟐𝟖 𝒅𝑩/𝒇𝒕 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐴𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 = 150 𝑓𝑡 × 0.028 𝑑𝐵/𝑓𝑡 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝑨𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒏𝒖𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏 = 𝟒. 𝟐 𝒅𝑩 15 Communications 4: Transmission Media and Antenna System & Design 2.1.6: Transmission Line Losses Radiation Losses → For analysis purposes, metallic TLs are often considered to be totally lossless. In reality, however, there are several ways in which signal power is lost in a TL. → Occurs because a TL may act as an antenna if separation of the conductors is an appreciable fraction of a wavelength. → Increase with frequency for any given TL, eventually ending the life’s usefulness at some high frequency. SUBHEADING 1 → Conductor Loss → Dielectric Heating → Reduced by properly shielding the cable. Coupling Loss → Radiation Loss → Coupling Loss → Occurs whenever a connection is made to or from a transmission line, or when two separate pieces of transmission lines are connected together. → Mechanical connections are discontinuities. → Discontinuities tend to heat up, radiate energy and dissipate power. → Corona “Spark” Corona Sparks → Deemed as the worst case of transmission line losses. Conductor Heating Losses → Increases with frequency because of skin effect. → A luminous discharge that occurs between two conductors of transmission line when the difference of potential between them EXCEEDS the breakdown voltage of the dielectric (insulator). → Skin Effect: → Once a corona has occurred, the TL may be destroyed. → Also called I2R Loss / Power Loss. - Phenomena wherein as the operating frequency goes higher, the tendency of the current is to travel on the surface or near the surface of the conductor. → Solutions to Skin Effect: 1. 2. 3. Increase the diameter of the conductor Let the conductor be plated with silver (electroplating) Use multi-stranded wire Dielectric Heating Losses → For solid dielectric lines (very observable). → Increases with frequency because of gradual worsening properties with increasing frequency for any dielectric medium. → For air dielectric, heating becomes negligible. 16