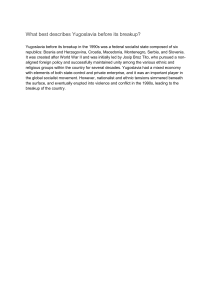

Socialist Yugoslavia was a country suspended between traditional cultures, competing concepts of modernization, and rivaling Cold War blocs. It produced a diverse body of architecture that defies easy classification and blurs the lines between the established categories of modernism. This book explores the historical “in-betweenness” of Yugoslav architecture by analyzing its key architectural and urban achievements in relation to their social, political, and cultural contexts. Yugoslavia is certainly the most miraculous of the “defunct countries” of the recent past: although it started to disintegrate more than twenty years ago, its past appears more modern than the present of many of its successor states, not only in an aesthetic but also in a more general, intellectual sense. Or is it a mere Fata Morgana of our senses, based on a selective perception? This book gives an answer that is supported by a careful analysis of a vast material, and not by an elegiac meditation on tempi passati. It shows a remarkable will of the architects to associate themselves with the program of modernism, but “floating” in an in-between, mediatory condition rather than fully embracing its ideology. This relationship to modernism meant broader horizons and the rejection of any concessions to the spirit of the province—while at the same time not shying away from its mythologies. Even if we accept that the past is not available to us in its immediacy, the texts and images in this book can conjure the power of the vision of a modern culture that was not monolithic, but open, generous, challenging, and inspiring; it had all the qualities that provincialism lacks, rejects, and wants to erase. Ákos Moravánszky Professor of Architectural Theory, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Author of Competing Visions: Aesthetic Vision and Social Imagination in Central European Architecture Lucid and compelling, written in a fluent style, this meticulously researched book, with its full array of beautiful photographs, is a landmark study of a place and time that produced stirring and original architecture. It is a convincing and insightful portrait of the era and a major contribution to our understanding of the broader history of modernism. In the end, the Yugoslav state was a failed political experiment, but in cultural terms—and especially in architectural terms—the attempt to make something “in-between,” to find a new “intermediate” aesthetic, led to great innovation and discovery. What one sees in these pages is revelatory, a still mostly unknown building scene of striking power and freshness. Christopher Long Professor of Architectural History, University of Texas at Austin, Author of The Looshaus ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book would not have been possible without the support from the ERSTE Foundation and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education, Arts, and Culture. To them we owe thanks for their generosity and patience. This book also would not have been possible without its subject: the many architects who practiced throughout former Yugoslavia. Over the years, many of them shared their knowledge and memories with us; sadly, some of them are not with us any more. Our gratitude and admiration go to: Ivan Crnković, Georgi Konstantinovski, Dragomir Manojlović, Boris Magaš, Milenija and Darko Marušić, Mihajlo Mitrović, Vladimir Braco Mušič, Aleksandar Stjepanović, Ivan Štraus, and Zlatko Ugljen. Let this book keep the memory of the late Bogdan Bogdanović and Boris Čipan, as well as all other talented architects whom we did not know in person, but who made the region so interesting to study. A great number of people helped us with this book. Kai Vöckler brought the three of us together for the irst time for the exhibition Balkanology; he was also Wolfgang’s travel companion on one of his irst photographic expeditions through the region. Producing the photos would not have been possible without those who opened the many doors of the buildings to be photographed. Particularly helpful were Divna Penčić in Skopje, Visar Geci in Prishtina, and the Ćosić family in Ljubljana. While working on this book, we also collaborated with more than thirty colleagues from all over the region on a research project titled Unfinished Modernisations—Between Utopia and Pragmatism: Architecture and Urban Planning in Former Yugoslavia and Successor States. The project slowed us down in finishing this book, but in return we gained so much more, as we all learned a great deal from each other. Some of the acquired knowledge informs this book. A big thank you to our UM crowd! Special thanks to Antun Sevšek, Matevž Čelik, Alenka di Battista, Jelena Grbić, Martina Malešič, Divna Penčić, Dubravka Sekulić, Elša Turkušić, and Nina Ugljen for helping us with the archival material. And last but not least, Jelica Jovanović has always been a most reliable collaborator and we owe her thanks for her tireless help. CONTENT Various individuals and institutions also kindly shared their archives with us. There are too many to name individually, but to all of them we owe gratitude. Special thanks to the colleagues who read the various parts of the text and shared their insights and comments with us: Tanja Damljanović Conley, David Raizman, and Danilo Udovički, as well as Katharine Wheeler and other South Floridians from the History/Theory Faculty Workshop at the University of Miami. Ákos Moravánszky and Dietmar Steiner provided help and intellectual support. Finally, Christopher Long toiled through the early versions of most of the chapters and nevertheless remained kind and supportive, for which we are especially grateful. Michael Jung generously put up with our constant demands and changes while designing this book. Philipp Sperrle at Jovis Verlag has been a patient and eficient editor. Vladimir thanks Professor Deirdre Hardy, Director of the School of Architecture, and Dr Rosalyn Carter, Dean of the College for Design and Social Inquiry at Florida Atlantic University, for allowing him to reshuffle his teaching schedule in the Spring and Summer of 2012 to make room for writing. Maroje thanks everyone at the Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb for academic collaboration and support. Special thanks to Professor Andrej Uchytil for stimulating discussions and access to the archives of the Atlas of Croatian Architecture, as well as to the editorial board and staff of Oris magazine for their kind assistance in image research. During the hectic final days of work on the book, Maroje and his life partner Maja welcomed their twins, Ivan and Eva; Maja, thank you for your patience and giving. Everyone mentioned, and those we forgot to mention: we owe you gratitude. Some credit for this book is yours; the errors are our own. Vladimir Kulić, Maroje Mrduljaš, and Wolfgang Thaler Fort Lauderdale, Zagreb, Vienna, July 2012. Preface – Reassembling Yugoslav Architecture Introduction 4 16 A History of Betweenness Between Worlds Between Identities Between Continuity and Tabula Rasa Between Individual and Collective Between Past and Future 20 30 74 118 164 214 Selected Bibliography Index Image Credits Imprint 266 269 272 272 4 PREFACE – REASSEMBLING YUGOSLAV ARCHITECTURE Did Yugoslavia ever exist? Jorge Luis Borges suggests in his stories that reality is shaped by percepts and ideas, not the other way around. The Despotate of Epirus, the Principality of the Morea, the Kingdom of Montenegro, Tlön and Uqbar—which of them existed at some point of history, which of them is fiction, a conspiracy of intellectuals to create a consistent world? We certainly think that the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia were not only real but are still very close to us—however, since we know that objects that we observe in the rear-view mirror are closer than they appear, the apparent closeness is probably a result of the correctional reflex of our historical consciousness. Yugoslavia is certainly the most miraculous of the “defunct countries” of the recent past: although it started to disintegrate more than twenty years ago, its past appears more modern than the present of many of its successor states, not only in an aesthetic but also in a more general, intellectual sense. Or is it a mere Fata Morgana of our senses, based on a selective perception? This book by Vladimir Kulić, Maroje Mrduljaš, and Wolfgang Thaler gives an answer that is supported by a careful analysis of a vast material, and not by an elegiac meditation on tempi passati. In my rear-view mirror, Yugoslavia certainly appears very close. As an architectural student of the Budapest Technical University during the early nineteen-seventies, research in architectural history proved to be a good escape from the tired functionalist doctrine in the design classes. I found myself embarking on a research project on medieval monastic architecture on the Balkans. It was my dream to visit Mount Athos, Hosios Loukas and the other famous orthodox monasteries, but Greece as a Western country was of-limits for Hungarian tourists—unlike Yugoslavia. So I decided to go there, heading to Ohrid in the south after a short visit at the Archaeological Institute in Belgrade, visiting as many of the medieval churches and monasteries on my way as I could. What interested me was how church typologies relected the changing political ties of the local rulers, mixing Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic forms. At that time, no KFOR was necessary to protect the sites; it was possible to spend the night in a small tent right at the marble façade of the monastery of Visoki Dečani, surrounded by high mountain peaks. As a hitch-hiker I met not only lorry drivers, but also backpackers from the United States and Western Europe, and we were all thrilled by the kaleidoscopic change of landscapes and languages, by the rich tapestry of cultures and tastes that Otto Bihalji-Merin—an important protagonist of regionalism avant la lettre—described in his popular books. I kept returning to Yugoslavia every summer, extending my itinerary continuously toward the West, and these journeys were accompanied by all sorts of music: starogradske pesme, gusle rhapsodies, and the strange harmonies and uneven rhythms heard on the buses on breathtaking hairpin highways. No other country I knew was as heavy in mythology. Talking in a generic “Slavic” to the drivers, I became increasingly familiar 5 with a space that was small and enclosed, unlike the highway we were moving on. The nation-building process that started with a language renewal in the nineteenth century still seemed to determine the patriarchal culture of these enclosures. This was a general phenomenon, but the particular topography and history of Yugoslavia resulted in an extremely tight-knit structure, with mountain chains and rivers protecting tiny but treasured local cultures, where even the smallest traces of foreignness would endanger the purity of the organic traditions. This was the enclosed world of the “province,” where— according to the Serbian philosopher Radomir Konstantinović—an agonizing tribal culture attempts to forget time and history. But the freeway was a reality as well, connecting worlds behind mountains, opening space. The modern cities or the large tourist complexes on the Adriatic coast created a large periphery as a field open for experiments, less ideological than the centers from which the ideas were taken, and then questioned, tested, and modified. Therefore, the modernism of Yugoslavia appeared as not only a modernism in-between, but in an inseparable symbiotic relationship with its Other, allowing the freedom of the periphery in conjunction with the parochial spirit of the province. A spatial assemblage of sorts, echoing the dilemma of the medieval builders of Dečani or Gračanica: Byzantine and Western, the necessity of a permanent reinvention of the country and the necessary adjustments of newly received ideas and ideologies. The questions raised by my travels in Yugoslavia during the summers of the early nineteen-seventies led to more systematic investigations of the architecture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its successor states, as an attempt to overcome the limitations of nation-centered historiographies. The discussion of “in-betweenness” and “mediatory architecture” in Kulić and Mrduljaš’s text refutes the widely accepted notion of the Iron Curtain and the consequent East/West dichotomizations of cultural phenomena according to this dispositive. The authors explore new concepts to understand the changing urban conditions and architectural production in socialist Yugoslavia, and Wolfgang Thaler’s photographs present the persuasive power of this architecture, resisting any temptation to capture the melancholy of a bygone era. Yugoslavia was a state emerging out of the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, which had already broken up once at the beginning of World War II. Most political models and social visions—from liberal bourgeois capitalism to nationalism, communism, Stalinism, self-governing socialism, and transitional post-socialism—swept through a country that was in the process of permanent reinvention of itself. Despite constant transformations, Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš show a remarkable will of the architects to associate themselves with the program of modernism, but “floating” in an in-between, mediatory condition rather than fully embracing its ideology. This relationship to modernism meant broader horizons and the rejection of any concessions to the spirit of the province—while at the same time not shying away from its mythologies. Juraj Neidhart’s or Bogdan Bogdanović’s search in this direction, their interest in the archaic, surreal and monumental, are cases in point. By reassembling the architecture of socialist Yugoslavia, the authors escape the constraints of an architectural history that is withdrawing behind safe borders. This withdrawal generally favors a “postmodern” historiography, suspicious of any kind of “monolithic” representation of the past. What usually remains in such presentations are objets trouvés from a defunct land, decontextualized fragments of an irredeemable past that is a burden on the present rather than a legacy. But even if we accept that the past is not available to us in its immediacy, the texts and images in this book can conjure the power of the vision of a modern culture that was not monolithic, but open, generous, challenging, and inspiring; it had all the qualities that provincialism lacks, rejects, and wants to erase. Ákos Moravánszky 8 9 Boris Magaš: Poljud Stadium, Split, 1976–79. 12 Milorad Pantović (architecture) and Branko Žeželj (engineering): Hall 1, Belgrade Fair, Belgrade, 1957. 13 16 17 INTRODUCTION Describing a region as in-between is a cliché. The label has been applied to places as varied as Austria, Turkey, Russia, Panama, various parts of the US, the Balkans, and all of Eastern Europe. Common toponyms are derived in such terms: from Mitteleuropa and Zwischeneuropa to the Middle East. Being in-between, in short, is a global state. Why, then, do we stick with a cliché in framing the topic of this book? We argue that the in-betweenness of socialist Yugoslavia was exceptional: the country condensed so many overlapping geopolitical and cultural in–between conditions that they became one of its defining features. Socialist Yugoslavia can hardly be described without mentioning at least some of the shifting reference points between which it was suspended: the superpowers of the Cold War, rival ideological systems, multiple ethnic identities of its own populations, varied versions of modernity and tradition, past and future. Such conditions necessarily affected architecture; and since existing in-between by definition requires simultaneously referencing multiple external standpoints, it is no wonder that Yugoslav architecture never developed an easily recognizable identity. Despite the occasional remarkable achievements, it could not be easily labeled and marketed, as was the case with the more successful “other modernisms,” such as those of Finland and Brazil. And even if all such identities are inevitably fabrications that edit a messy reality for easier consumption, the fact remains that no one even attempted to fabricate one for socialist Yugoslavia. So why even bother paying attention to a defunct country? The irst reason has to do with the possibility that socialist Yugoslavia might teach us something useful for our current cultural moment. While peripheral to the world’s cultural and political centers, it “loated” between them, rather than clearly gravitating to any. The fragmented body of architecture that came out of that condition resulted from the need to mediate between a wide variety of contradictory demands and inluences, pitching multifarious global forces and the diverse interconnected localities against each other. Such mediation should resonate with our times of “liquid modernity,” as Zygmunt Bauman has termed it, characteristic for its radical cultural pluralism and the related, increasingly ubiquitous and self-conscious practices of hybridization, recycling, sampling, and blending.1 All of these practices function as mechanisms of mediation, understood as processes of reconciling diferent or conlicting forces, assumptions, concepts, or models. But mediation does not necessarily result in cultural syncretism; it assumes a much broader range of strategies, covering the full spectrum between outright resistance and wholesale appropriation, such as adaptation, reinterpretation, recombination, subversion, etc. In socialist Yugoslavia, such mediatory strategies were simultaneously employed both within the ields of politics and architecture—each with its own multiple ideologies and geopolitical constellations—as well as in the complex relationships between the two. It is these interconnected parallel mediations 2 3 4 1 Bauman (2011). Nancy Condee, “From Emigration to E-migration: Contemporaneity and the Former Second World,” in Smith, Ewenzor, and Condee (2008), pp. 235–36. IRWIN (2006), Piotrowski (2009). On Bosnia and Herzegovina, see Štraus (1998). On Serbia, see Perović (2003). On Slovenia, see Bernik (2004). that we hope to sketch out here, also looking for those instances when architects were able to transcend their “loating periphery” and become their own centers. The second reason for this book comes from the fact that the architecture of the socialist “Second World”—“the distinct, if ultimately truncated limb of modernity’s tree,” as Nancy Condee has cogently described it 2 —is perhaps too slowly becoming recognized as part of the global modernist heritage. Yugoslavia was an important branch of that truncated limb; yet the extent to which its architecture was typical or exceptional is still to be determined, since the socialist world is far from being charted in that respect. Artists and art historians have been very active in producing such charts in their own field; in architecture, however, there are still no equivalents to books like IRWIN’s East Art Map and Piotr Piotrowski’s In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945–1989. 3 Instead, photographers are taking the lead, with all the inherent strengths and dangers of such an approach. A recent wave of photographic monographs presents the buildings of the socialist East as if they were relics of some long-lost civilization: sad, dilapidated concrete mastodons, anonymous in their spectacular oddity, defying interpretation and lacking any meaning relevant for the present moment. These publications certainly have some merit, since they dispense with one entrenched stereotype that identified Eastern Europe with monumental figural socialist realism; but they fall into another trap by suggesting a certain uniformity of architecture across the region and across the period, offering far too simplistic interpretations. The socialist world and its concomitant architectural phenomena were in no way monolithic, either transnationally or within individual countries, not even within the same genre of architecture. Not all buildings from the socialist period are dilapidated; not all of them are enormous brutalist structures; and most are surely not stripped of meaning. Alleging a certain formal or visual essence of “socialist modernism” makes just as much sense as trying to identify inherent aesthetic features of a “capitalist modernism,” a label that no one but the most hardened socialist realist critic would take seriously, because it too broadly equates cultural and political categories. This book is, therefore, an attempt to contribute a piece to the puzzle charting postwar architecture in Eastern Europe. In part, it is itself a photographic monograph: photos possess the kind of persuasive power that words do not, which is important when introducing a generally unknown body of architecture. Wolfgang Thaler spent three years touring former Yugoslavia and recording the buildings produced during the socialist period. What emerges from his photos is not only a great variety of building types, technologies, and aesthetic approaches, but also the greatly varied destinies that the region’s structures and cities experienced since the collapse of the socialist federation. Many buildings are indeed dilapidated, some damaged beyond repair, and some even resurrected from scratch after total demolition during the wars of the nineteen-nineties. Most, however, still constitute functioning built environments, architecturally superior to the current commercial vernacular, not to mention the sea of unregulated construction or the attempts at retraditionalization that have swamped large parts of the region during the transition to capitalism. On the other hand, the recent stand-out achievements, some of which have attracted international attention—especially those from Slovenia and Croatia—have not emerged out of thin air, but instead continue the well-established modernist traditions that were decisively solidified during the socialist period. Complementing the photos, the essays in this book aim at providing a broad framework for understanding the built environments throughout the region. Treating the former country as a whole may fly in the face of the common assumption that socialist Yugoslavia’s constituent republics developed distinct, self-contained architectural cultures that did not share very much. Indeed, several twentieth-century architectural histories of the individual successor states have already appeared in English since the collapse of the federation in 1991. 4 They are all valuable sources, but their particularistic perspectives preclude them from addressing some important phenomena that were common to 22 23 Architecture’s Melting Pot Of all the Nazi-occupied countries, Yugoslavia is most in the news and least known as a place. When American troops land there many will wonder that geography books ever classed it as a European country. Veiled women, bearded priests, towering minarets contribute eastern lavor. But that isn’t all. In crumbling old towns held to the hillside by fortress-like retaining walls are some of the most modern schools and ofice buildings in Europe. No record could express more vividly Yugoslavia’s contradictory political, social and cultural currents than does its building pattern. Architectural Forum, November 1944 European or “eastern?” Modern or stuck in the past? Such questions were long associated with the region that once comprised Yugoslavia, often falling in the category that Maria Todorova famously termed balkanism.1 Architectural Forum’s romantic image restated such stereotypes, although it was not entirely incorrect in suggesting that large parts of the country had only recently embarked on the road to modernization. But on one account the magazine was dead wrong: American troops would never land in Yugoslavia. Instead, the country was liberated through joint eforts of local Communist-led partisans and the Red Army, a fact that would determine its fate for the decades to come. Thus, Yugoslavia’s road out of underdevelopment led not through the US-sponsored Marshall Plan, but through a unique model of socialist modernization, following a winding path of shifting international alliances and perpetual revisions of the political and economic system. As the Cold War settled in, Yugoslavia came to occupy a place halfway between the two ideological blocs, at the same time developing its own brand of socialism based on workers’ self-management. In the process, all parts of the country, regardless of their varied levels of development, experienced the most intense period of industrialization and urbanization in their respective histories. The resulting cities and buildings still comprise the bulk of the region’s built environments even twenty years after the federation’s demise. Socialist Yugoslavia was “one of the most complicated countries in the world,” as two American scholars once observed. 2 It was popular to describe it (not entirely precisely) as one country with two alphabets, three languages, four religions, ive nationalities, six constituent republics, and seven neighbors.3 It emerged from World War II as the staunchest Soviet ally, only to stun the world by its sudden expulsion from the communist bloc just three years later. It then briely allied with the West, before becoming one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. It was governed by a single party, but strove towards radical democratization. Its economy was planned, but included signiicant elements of the market. It promoted collective welfare, but also had a well-developed consumer culture. It developed distinct national cultures, yet was bound by a common state. It strove towards a bright future, but its utopian horizon always included perspectives to the past. In order to make any sense of such complexity, it is indispensable to start with distant history. Before the world was split by the Cold War, there were several other pairs of the East-West divide that deined the region, dating back to the division of the Roman Empire at the turn of the fourth century. The two emperors who instituted that division, Diocletian and Constantine the Great, were both born on the territory that would later become Yugoslavia. Both were also responsible for extensive architectural programs, as was another native son of the region, Emperor Justinian, the patron of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Architectural remnants of the Roman times constitute the irst important cultural layer ubiquitous throughout the region, Diocletian’s Palace in Split being its most famous example. After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Slavic tribes settled in the region around the seventh century. They were converted to Christianity in the ninth century, but were soon split by the Great Schism of 1054 between the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Church. The border again went right across the region, causing its own architectural ramiications. The area in the southeast came into the sphere of the Byzan- 1 2 1 2 1 2 3 Todorova (1997). Hofman and Neal (1962), p. ix. After 1968, Bosnian Muslims—today known as Bosniaks—were recognized as the sixth nationality. The walled historical core of Dubrovnik. Fortiications dating mainly from 12th–17th centuries. Mimar Hayruddin: Old Bridge, Mostar, 1557–66. Demolished in 1993, rebuilt in 2004. tine tradition, while the northwest embarked on the standard Western stylistic sequence of Romanesque-Gothic-Renaissance-Baroque. The division, however, was not clear-cut and was blurred by hybrids like some Serbian Orthodox monasteries, which combined the Byzantine domed typology with Romanesque and Gothic decoration. The situation was further complicated in the late Middle Ages by the rise of inluential heresies, such as the independent Bosnian Church and the dualist Bogomilism. Persecuted by both Orthodox and Catholic churches, these heresies would be celebrated in the twentieth century as the harbingers of an authentic South Slavic identity and precursors to the modern resistance against outside oppression. Their most well-known remnants are the monumental carved tombstones called stećci, tens of thousands of which are scattered throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Montenegro, Croatia, and Serbia. The Ottoman conquest swept through the region in the fourteenth and ifteenth centuries, expanding further and further north, until it swallowed everything except for a narrow strip along the coast of the Adriatic, which was the domain of the Venetian Republic, and the corner north of Zagreb, which was under the Habsburgs. The Ottomans introduced a third major religious group by converting large segments of the native populations to Islam. A fourth one appeared at the end of the ifteenth century, after the expulsion from Spain of Sephardic Jews, who settled in urban centers, such as Sarajevo and Belgrade. The border between Habsburg and Ottoman Empires more or less stabilized after the failed Turkish Siege of Vienna of 1683, dividing the region into three large spheres, which could be crudely described as Central European, Balkan, and Mediterranean. Centered in Vienna, Austria ruled north of the Sava and the Danube, replacing the physical traces of Turkish rule with new, regulated settlements and Baroque architecture. Centered in Istanbul, Turkey held power in the southeast with its characteristic organic cities and domed monumental buildings. Finally, Venice’s continued domination of the coast channeled the inluence of Italian architecture. In a way, the whole region functioned at this time as a collection of frontier zones, setting up segments of native populations as “bufers” against the neighboring rival empires. But the borders did not coincide with the distribution of ethnic or religious groups, which was further complicated by numerous migrations within the region, as well as from without. What is striking about the resultant built environments is that they brought large architectural traditions into proximity that is rarely found elsewhere. Eighty kilometers divide 32 33 tural profession as it struggled to envision the new institutions of the socialist state. Prior to 1948, the short-lived political attempts to impose socialist realism caused friction with the already entrenched modernism; after the break with Stalin, the resultant flourishing of modernist culture became a signifier of cultural freedom and, consequently, of Yugoslavia’s “break with Russia” and its distinction from other socialist states. Such polarizing interpretations, however, eventually died out as modernism—more or less openly— again became widely acceptable in the Eastern bloc in the nineteen-sixties. By that time, however, the ambitions of Yugoslav foreign policy went far beyond simply maintaining national independence; instead, Tito was shaping the country into a global actor whose prominence greatly exceeded its size. 2 As a symbolic display of such position, Yugoslavia hosted a series of high-profile international events—including the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo—all of which required the construction of extensive new facilities, allowing architecture to further exercise its representational potential. East? West? Or Both? Hoffman and Neal, Yugoslavia and the New Communism, 1962.1 Scholars often use architectural metaphors to describe the Cold War world: walls, curtains, fences, and blocks. If its divisions physically coalesced in the Berlin Wall, in Yugoslavia they dissolved into an “open plan,” in which Europe’s two halves met not only metaphorically, but also physically. Yugoslavia was a rare place where the citizens of both Eastern and Western Europe could meet as they vacationed together on the Adriatic coast. At the same time, the country maintained equidistance from both blocs, while building its own alliances with the Third World through the Non-Aligned Movement, in an attempt to foster international relations based on partnership rather than neocolonial hegemony. That position, however, was only attained after a series of violent twists and turns in foreign policy, not unlike a pendulum swinging between the poles of the Cold War with decreasing amplitude to finally settle down in the middle. From the Soviet Union’s closest ally in the first postwar years, to the brink of joining NATO in the midnineteen-fifties, and then to one of the leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement in the early nineteen-sixties, Yugoslavia fluctuated between the so-called First, Second, and Third Worlds, before finally reaching a point of balance in which it was tied to all three, while effectively being a part of none. Such shifts inevitably affected architecture by engaging it in an increasingly globalized network of international exchange. If the modern architectural profession originally arrived in the region from the cultural centers of Central Europe—Vienna, Zurich, Prague, and Budapest—with time, reference points became increasingly distant, including at first Paris and Berlin, and after World War II Moscow, New York, Amsterdam, Brasilia, etc. The swings in the foreign policy also made them less stable. Yugoslav architectural journals in the late nineteen-forties focused almost exclusively on the news from the Soviet bloc, but by the early nineteen-fifties they completely shifted attention to Western Europe and the United States, and for some time also to the emerging centers of modernism outside of the traditional West, such as Brazil and Finland. After Stalin’s death and the subsequent “thaw” in the relations with the USSR in the mid-nineteen-fifties, architectural interactions with some East European countries, such as Poland, significantly strengthened as well. Soviet architecture was never again considered a model worth emulating, but Eastern Europe became an important market for Yugoslav construction companies and their in-house designers. At the same time, the involvement in the Non-Aligned Movement opened up an even more expansive new market in the Third World, providing Yugoslav architects with major urban, architectural, and infrastructural commission across four continents. The profession thus found itself at the intersection of an international network facilitating the exchange of architectural expertise between the First, Second, and Third Worlds, and thus effectively defied the seemingly insurmountable divides of the Cold War era. The changes in foreign policy also influenced architecture’s representational role as defined by the broader framework of the “cultural Cold War.” Between the end of World War II and the late nineteen-fifties, architectural style was an important signifier of political allegiance. The Soviets imposed socialist realism as the only acceptable aesthetic in their sphere of influence; it was generally identified with classical rules of composition, traditional ornament, and an overblown sense of monumentality, but in reality never unambiguously defined. In direct opposition to conservative Soviet aesthetics, the West appropriated high modernism as a signifier of liberal democracy, thus breaking architectural avant-garde’s historical linkage with revolutionary politics. Yugoslavia’s most extreme political fluctuations coincided precisely with the period when such aesthetic confrontations were at their height, creating a great deal of tension within the architec- 2 1 Hofmann and Neal (1962), p. 417. 3 For a detailed account, see Jakovina (2011). Kulić (2009), pp. 23–44. In Soviet Orbit In their infamous “percentages agreement” of 1944, Stalin and Churchill cynically concurred that their interests in postwar Yugoslavia would be shared fifty-fifty. But as the Communist Party took power, thanks to its leading role in the liberation war, it was already clear by May 1945 that Yugoslavia would side 100 percent with the Soviet Union. What ensued was a radical restructuring of the whole country, following the Soviet models in almost everything, from the constitution to cultural policy. At the same time, the wartime alliance with Western powers quickly deteriorated to open animosity and Yugoslavia found itself deeply immersed in the nascent Cold War as the Soviet Union’s most faithful satellite. Refusing to participate in the US Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe, the country instead tied its economic fortunes to the USSR, and was selected as the seat of the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform), the Sovietdominated international organization of communist parties. Following the Soviet example, the communist government immediately moved towards creating a highly centralized economy and culture. By 1948, the state took virtually complete control of all means of production; private architectural offices were abolished and the profession was reorganized into large state-owned design “institutes.”3 These offices were also intended to play an important role in the wildly unrealistic Five-Year Plan, inaugurated in 1947 after the Soviet model, which was intended to fully modernize the country in that short period. Such ambition, however, amounted to little more than wishful thinking: besides the rampant material shortages and a lack of modern technology, the largely rural country also lacked the educated cadre—including architects—that would be able to realize such a plan. The bulk of architectural production thus amounted to utilitarian buildings of modest material standard and limited conceptual or aesthetic ambitions. At the same time, cultural production came under total control of the Communist Party’s propaganda department, Agitprop, which imposed the monopoly of socialist realism in visual arts and literature. The doctrine favored traditional methods of realistic representation and themes that celebrated socialism, at the same time condemning modernism in its many guises as “bourgeois formalism.” Architecture was to follow suit with other arts, but the imposition of the Soviet doctrine proved problematic. Although the pages of the only architectural journal of the period, Arhitektura, were flooded with the images of monumental Soviet structures, few of the published local projects resembled such models. What stood out from the sea of utilitarian buildings were not the Yugoslav versions of Moscow’s Stalinist skyscrapers, but self-consciously functionalist structures, like Marjan Haberle’s Zagreb Fair (later converted to Technical Museum), which testified to continuity with prewar modernism. pp. 50 –51 Such discrepancy resulted from the fact that Yugoslavia’s new architectural elite consisted predominantly of leading prewar modernists and their young disciples. Many of 38 39 Vojislav Midić and Milan Đokić: Workers’ University “Radivoj Ćirpanov,” Novi Sad, 1966. 2|3 Mihailo Janković and Dušan Milenković: Building of Social and Political Organizations, New Belgrade, 1959–64. 4 Mihailo Janković and Dušan Milenković: Project for the Building of Social and Political Organizations, New Belgrade, c. 1959. Perspective. 1 1 2 3 4 1 2 The political connotations of this aesthetic shift became obvious in the foreign and particularly American interpretations, which saw Yugoslav modern art and architecture—in the words of Aline Louchheim, The New York Times art critic and Eero Saarinen’s wife—as a tangible proof of “Tito’s break with Russia.”11 No one put it more explicitly than Harrison Salisbury, the Pulitzer-Prize winning correspondent of the same paper. In a 1957 article illustrated with the yet uninished building of the Federal Executive Council, he wrote: “To a visitor from eastern Europe a stroll in Belgrade is like walking out of a grim barracks of ferro-concrete into a light and imaginative world of pastel buildings, ‘flying saucers,’ and Italianate patios. Nowhere is Yugoslavia’s break with the drab monotony and tasteless gingerbread of ‘socialist realism’ more dramatic than in the graceful office buildings, apartment houses and public structures that have replaced the rubble of World War II. Thanks in part to the break with Moscow and in part to the taste of some skilled architects no Stalin Allées, Gorky Streets or Warsaw skyscrapers mar the Belgrade landscape.”12 By the time Salisbury wrote these words, Yugoslavia was already a willing recipient of American cultural propaganda. Jazz musicians—such as Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong—were received with standing ovations.13 “The Family of Man,” an ambitious photographic exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern 3 4 Dušanka Menegelo, Soija PaligorićNenadović, Nadežda FiliponTrbojević, Vesna Matičević, and Vladislav Ivković: Belgrade Airport, Belgrade, 1961. Zdravko Bregovac: Ambasador Hotel, Opatija, 1964-66. Mihailo Janković: Project for the redesign of the Federal Executive Council Building, 1954. Sketch. Milivoje Peterčić: Feroelektro Ofice Building, Sarajevo, 1962. That is how Louchheim interpreted Yugoslav modernist art at the Biennial of Art in Sao Paulo in 1953, thus providing a precedent for many similar interpretations; Louchheim (1954). 12 Salisbury (1957). 13 Marković (1996), p. 471. 11 “276,000 Yugoslavs See ‘Family of Man’ Photos,” The New York Times (February 26, 1957). 15 Savremena umetnost u SAD (1956). 14 1 2 3 4 Art in New York, attracted its largest audience not in Paris or London, but in Belgrade in 1957.14 Another major MoMA exhibition, “Contemporary Art in the USA,” arrived in Belgrade in 1956 at a direct request of the Yugoslav side.15 The exhibition was remembered for introducing Abstract Expressionism to Europe, but it also showcased the latest architectural achievements, especially the icons of the International Style, including: SOM’s Lever House in New York, featured on the cover of the catalogue; Mies van der Rohe’s Lake Shore Drive towers in Chicago; and Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Soon after the exhibition, glass curtain walls replaced the recent Corbusian epidemic. By the end of the decade, buildings modeled on the Lever House, combining horizontal and vertical slabs encased in light curtain walls—at the time, significantly, known as “American façades”—appeared in every major Yugoslav city. p. 57 After the unsuccessful competitions of the late nineteen-forties, the realized ver- 56 57 Dragoljub Filipović and Zoran Tasić: Belgrade Youth Center, Belgrade, 1961. 70 71 Ivan Štraus: Holiday Inn Hotel, Sarajevo, 1983. Marjan Hržić, Ivan Piteša, and Berislav Šerbetić: Cibona Center, Zagreb, 1985–87. 76 77 I know that I cannot speak about architecture in Slovenia without starting with Plečnik, because we have almost no question today that is not somehow related to him—Plečnik laid the foundation of recent Slovenian architecture. Dušan Grabrijan, Plečnik and his School, c. 19481 From the irst pre-Romanesque creations to Viktor Kovačić, building in Croatia followed the logic of mason-architect’s thought, which intervenes in the realities of life—space and its laws, real economic and social structure, utilitarian and aesthetic demands—rejecting all the “stylistic” canons and patterns. It is precisely this astylistic character, which our own art history … considered backward and which foreign art history considered barbaric, that we today ind to be of supreme value, because it reveals a creative method that our time accepts as the most contemporary. Neven Šegvić, “Architectural modernism in Croatia,” 1952 2 In Bosnia, it is about two poles of architecture, about two ields of inluence—eastern and western—that in this ambiance seek reconciliation. Here we see the intertwining of the western rational inluence with the eastern emotional.… Because the opposites attract, it is no coincidence that the Oriental so adores technology and that the Westerner is so attracted by eastern architectures. We want to forge a synthesis of the rational and emotional, we care about a harmonious contemporary architecture, which will match new needs, new materials and technologies and will be, in our own language, understandable to our people. Juraj Neidhardt and Dušan Grabrijan, Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity, 19573 The question of regional differences in architecture is … similar to the question of language. If the language is the most authentic characteristic of a nation, then architecture is the most permanent one.… Some characteristics in the expression, like pitched roofs, bay windows, eaves, a rhythm of volumes closely connecting the building with its ambience and its site of existence, are only the indicators of the time when the idea originally emerged. Živko Popovski, in Macedonian Architecture, 1974 4 In the Serbian architecture of the recent times, since the middle of the 19th century, one notices a constant presence of the romantic spirit.… There are many reasons to believe that the romantic spirit is immanent to domestic architecture, thus giving rise to the predominance of complex forms and a certain compositional disorder over the classical sense of order and simplicity. Zoran Manević, Romantic Architecture, 1990 5 That Slovenian architecture was decisively marked by Plečnik, Croatian architecture “astylistic,” Bosnian architecture “a synthesis of the rational and emotional,” Macedonian architecture rooted in the vernacular, and Serbian architecture “romantic” are obvious simpliications aimed at identity-making. There were numerous Serbian architects who designed perfectly rationally, there were Croats who produced “stylistic” architecture, and there were Macedonians who were emphatically cosmopolitan. Yet, the quoted statements testify to the widespread assumption that Yugoslavia’s constituent nationalities possessed their own distinct architectural identities that relected certain transhistorical continuity. Indeed, architectural historiography of the period was based on that assumption; the key texts were organized according to republican borders, rather than any pan-Yugoslav criteria.6 Conversely, no one tried to formulate what would be speciically Yugoslav to architecture in Yugoslavia. If Yugoslavia as a whole was ever architecturally represented—for example, through Vjenceslav Richter’s pavilions—its deining features were the project of socialist self-management and its independent foreign policy, rather than any overarching identity based on a common cultural essence. 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grabrijan (1968), pp. 175–176. Šegvić, (1952), pp. 179–185. Neidhardt and Grabrijan (1957), p. 14. Popovski (1974), p. 40. Manević (1990), p. 5. Manević et al. (1986), Štraus (1991). 8 On the construction of Belgrade, Zagreb, and Ljubljana as the national capitals of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, see Damljanović (2003); on the construction of a Yugoslav architectural identity, see Ignjatović (2007). The Department of Architecture at the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Podgorica was founded in 2002 and an independent Faculty of Architecture in 2006. This situation was largely a consequence of the federalist organization of the state, which in turn acknowledged the existence of the more or less formed identities of its constituent nationalities. In the interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia, those identities were supposed to blend, culturally and architecturally, into a single one; but due to the lawed political dynamics of the monarchy, the project of cultural uniication never took of.7 The Communist Party owed its pan-Yugoslav success partly to its promise of allowing political and cultural autonomy to all constituent nationalities; the ones it recognized as such were not only Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as did the interwar monarchy, but also Macedonians and Montenegrins and, as of 1968, “Muslims by nationality”—today’s Bosniaks. The guarantors of such autonomies were the six constituent federated republics. Five were organized as nation-states and the sixth one, Bosnia and Herzegovina, was home to three nationalities (“narod”), Muslims, Serbs, and Croats. All six republics had sizable ethnic minorities (“narodnost”), most populous among them Albanians, Hungarians, and Italians. Serbia also had two autonomous provinces, Vojvodina and Kosovo, which recognized both their historical identities and the presence of non-Slavic populations. The fact that at the beginning of this chapter we could not quote a statement regarding Yugoslavia’s smallest republic, Montenegro, reveals something about the way in which architectural identities were constructed. During the socialist period, Montenegro was the only Yugoslav republic that did not have its own school of architecture; the relative lack of discourse about Montenegrin architecture thus seems to conirm the centrality of educational institutions in forging the corresponding national identities. 8 Belgrade, Zagreb, and Ljubljana all entered the socialist period with the previously established architecture departments at universities, and additional two were founded in Sarajevo and Skopje shortly after the war. (A sixth one, in Priština, was not founded until the nineteen-eighties, so its impact during the socialist period was limited.) Over time, these schools developed more or less distinct proiles, deined by the most prominent practitioners, who were often also the most inluential professors. The professional and academic elites thus generally overlapped. The schools were the centers of architectural research. They had their charismatic personalities with devoted followings. They also included theorists, critics, and historians, who were able to articulate discourses. In short, they allowed for the construction and reproduction of the more or less coherent architectural cultures, and since the schools were national, the resulting cultures came to be perceived as national as well, whether or not there were any deliberate attempts at deining national identities. The fact that professional organizations were also organized according to the republican borders only strengthened such apparent coherence. Unsurprisingly, distinguishing between the diferent schools based purely on their products would be tricky, not only because much of architectural production unavoidably falls into the category of the generic, determined by the broad social and economic conditions, but also because certain global trends, like high modernism in the late nineteen-ifties, periodically swept through the entire country. Yet, certain phenomena were speciic to individual schools, endowing them with a local character that may or may not have been related to any speciic national content. These phenomena could manifest themselves on the representational level as stylistic preferences or as attempts to engage with the local vernacular architectures, but they also emerged as the result of mastering certain typological or technological themes in response to the speciic problems of the region. One such instance was the extensive experimentation with the morphology of tourist facilities on the Croatian coast in the nineteen-sixties and -seventies; another was the so-called Belgrade apartment, a characteristic residential plan developed in response to the booming construction of mass housing. Nation-based architectural cultures were related to, but ultimately distinct from the question of the representation of national identities. That question was posed with particular force in conjunction with the establishment of Yugoslavia’s six constituent republics as states, with their own capitals, seats of political power, and national cultural institutions—all buildings with inherent representational potential. Despite their varied histories 86 87 practitioners into an unbroken chain of inluences across a century of modern architecture. Slovenian architects—Ravnikar included—were exceptionally successful at architectural competitions around Yugoslavia, spreading their taste for expressive structural igures to other republics. Architects like Milan Mihelič, Marko Mušič, and Miloš Bonča worked all around the country on important civic and commercial commissions. pp. 192–93, 196 (above), 244 (below) More often than not, these projects replaced Ravnikar’s intricately patterned cladding and ine details with bold shapes in exposed concrete, closely uniting structure, form, and spatial envelope. 1 2 3 1 2 3 Cankarjev dom. At the urban level, the project mediates between the local scale of the surrounding historical blocks and the scale of the whole city, as the two towers dominate Ljubljana’s skyline. Their cantilevered pointed tips, however, face each other at a close distance, forming a colossal “gate” and engaging—much like the rest of the complex—in an interplay between the monumental and the intimate. Instead of Le Corbusier, here one may trace references to Alvar Aalto’s late work, such as the Finlandia Hall in Helsinki, which are especially recognizable in the congress center: cladding in thin stone slabs arranged in long narrow strips, copper roofs covered with a green patina, and the complex, broken-up forms. Yet, Ravnikar’s Central European roots are still abundantly visible, particularly in the duality of the expressive structural “core” and the variety of claddings. The latter included not only the “woven” brickwork, known from his earlier projects, but also the exaggerated rivets used to attach stone slabs to the façade, directly evocative of Otto Wagner. Ravnikar’s explorations of tectonics evolved through the agency of his many students into an overall “taste for structure,” as the architectural historian Luka Skansi recently termed it, which became a running theme for Slovenian architects throughout the nineteen-sixties and -seventies.17 Indeed, both Ravnikar and his followers experimented in this period with a variety of materials and structural systems, predominantly reinforced concrete, but also steel, prestressed prefabricated concrete elements, and suspension cables, which they embraced not only for their utilitarian advantages, but also as the sources of expressive igures. Imaginative ways of articulating and exposing the structural core of a building, while remaining true to the logic of statics, were sought not only in building types that naturally called for such experiments, like industrial sheds or department stores, but also in residential and civic buildings. The development symbolically marked the transition from a craft-based, small-scale production of architecture to a modern industry, thus updating Plečnik’s attention to material expression and meticulous details for the late twentieth century. Yet even this trend had a precedent in Plečnik’s work: his 1911 Church of the Holy Spirit in Vienna, built in exposed reinforced concrete, with a slender “Cubist” skeleton in the crypt and the spectacular clerestory beams spanning the length of the nave. Remarkable transhistorical continuity was thus established, linking 17 Stanko Kristl: Residential and Commercial Building, Velenje, 1960–63. Milan Mihelič: Department Store, Osijek, 1963–67. Miloš Bonča: Department Store in Šiška, Ljubljana, 1960–64. Luka Skansi, “A “Taste” for Structure: Architecture Figures in Slovenia 1960-1975,” in Mrduljaš and Kulić (2012), pp. 424-35. 18 Frampton (1983), p. 21. Balkan Regionalisms between Criticality and Representation During his famous Voyage d’Orient in 1911, the young Charles-Edouard Jeanneret passed through the Balkans in search of an authentic traditional culture uncorrupted by modernity. Taking the boat down the Danube, he arrived in Belgrade to ind a city that was already beyond rescue, but then went on into the Serbian countryside, where he was enchanted by folk art and architecture. And while he did not venture much further into what would soon become Yugoslavia, in Bulgaria and Turkey he continued exploring the kind of vernacular architecture that was common to much of the Balkans. The lessons he learned on that trip provided a crucial formative experience for transforming Jeanneret into Le Corbusier. Even before World War II, Yugoslav modernists began retracing Le Corbusier’s steps, discovering their own vernacular both as a subject of academic study and as an inspiration for contemporary work. These eforts intensiied after the war, boosted by socialism’s concerns for the cultures of the “people,” the developing ethnography, and the need to formulate the identities of the newly forged republics. At irst, socialist realism—with its credo “socialist in content, national in form”—produced a few literal interpretations, but rural and urban vernacular ultimately became the raw material to be reinterpreted in modern terms. The methods ranged from direct citations of forms and motifs, to “critical” distillation of abstract principles or, as Kenneth Frampton has put it in his famous argument on critical regionalism, mediating the “impact of the universal civilization with elements derived indirectly from the peculiarities of a particular place.”18 The motivations similarly ranged from explicit representations aimed at identity-making to sensitive responses to natural or cultural contexts. But there was never a coherent regionalist “school”; any such attempts were overshadowed by the universalizing march of modernity even in the cities like Sarajevo and Skopje, where the traditions of urban vernacular still survived in the environments of strong local character. Yet, in the crevices of mass urbanization, regionalist eforts produced a handful of outstanding achievements that transcended the narrow requirements of both rapid modernization and explicit national representation. One of the pioneers of documenting and analyzing the Balkan vernacular heritage was yet another Plečnik’s student, Slovenian architect Dušan Grabrijan. He began his research in Bosnia in the nineteen-thirties and expanded it after the war to Macedonia, producing a series of exquisitely illustrated publications, many of which came out after his untimely death in 1952. Enchanted by the “Oriental” architecture he irst encountered in Sarajevo, Grabrijan argued that it closely resonated with Le Corbusier’s own work through its “cubist” forms, open spatial arrangements, and close relationship with nature. In his eforts to update the local tradition for modern times, Grabrijan found an important ally in his friend Juraj Neidhardt, a Croatian architect with remarkable international experience, which included working for Peter Behrens and Le Corbusier and exhibiting with the avant-garde circles in Paris in the nineteen-thirties. Neidhardt applied the results of Grabrijan’s analysis in practice, producing a series of regionalist buildings around Bosnia in the late nineteen-thirties. The apex of collaboration was the book Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity (1957), prefaced by Le Corbusier himself. Architecture of Bosnia claimed that, with its unpretentious emphasis on comfort instead of monumentality, Bosnian “Oriental” house, was in its essence already modern, requiring only certain technological updates to become the basis for the region’s modern architecture.19 100 101 Miroslav Jovanović: Apartment Building in Pariska St., Belgrade, 1956. Mihajlo Mitrović: Apartment Building at the corner of Braće Jugovića St. and Dobračina St., Belgrade, 1973–77. 116 117 p. 116–17 Zlatko Ugljen: Šerefudin White Mosque, Visoko, 1969–79. 120 121 After the war, the urban design we had in mind was not only something new and momentous, it was far more than that: a premonition of a knowledge of what could be, the expectation of a solution to all problems, be they social, technological or aesthetic in nature… All of a sudden these kinds of illusions and endeavors knew no more ideological or material obstacles. Or rather, we did not see them as there has never existed a society nor a man who, when in this kind of situation, would not freely let their mind wander through thoughts of a better future and its realization in an inviting, utopian vision. Edvard Ravnikar, 19841 And if, with ilial thoughts and feelings, you enthusiastically seize the opportunity of giving new life to certain accords of the past which may be found again in some common elements (as e.g. in a way of paving, a way of building, a special quality of mortar, a certain way of carving and working the wood, in a local and national human scale relected in the selection of certain dimensions, etc.) you will build a bridge over the chasm of time and will, in an intelligent way, become the son of your father, a child of your country, a member of a society conditioned by history, climate, etc.—and yet remain a citizen of the world—which is more and more becoming the common fate of all mortals on earth. Le Corbusier in the Preface to Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity, 1952 2 In order to build socialism, a country needs an urban working class. At the end of World War II, Yugoslavia was neither urbanized nor industrialized: just a tenth of its population lived in cities with over 20,000 residents, and only two cities, Belgrade and Zagreb, had more than 100,000 residents. More than two-thirds of Yugoslavs depended on agriculture and more than a quarter were illiterate. 3 To make it worse, much of the modern infrastructure—already modest by the standards of the developed world—was destroyed in the war, including almost one million buildings, a third of all industrial plants, and half of railway tracks. Major cities lay in ruin. As the sine qua non of socialism, fast urbanization thus became one of the primary goals of the new communist government. Indeed, in the following quarter century Yugoslavia was thoroughly transformed. By 1971, due to a massive migration from rural areas, the urban population rose to 40 percent and non-agricultural to over 60 percent. The illiteracy rate was reduced to less than a tenth, mostly accounted for by the elderly in the undeveloped rural areas in Kosovo and Bosnia. Republican capitals took the lion’s share of urban growth: Belgrade and Zagreb roughly doubled their populations, Sarajevo grew 2.5 times, and Skopje more than tripled in size. 4 The same trend continued steadily through the remainder of the socialist period. By the end of it, greater Belgrade had a population of over 1.5 million, Zagreb close to a million, Sarajevo over half a million, and Skopje 450,000. Urban living, before World War II reserved for a tiny minority, became everyday experience for at least a half of the population. Yugoslav cities thus became machines for remaking people. They forced massive segments of the population to leave their old ways behind and adapt to a new urban life. How were these “machines” conceptualized and realized? How was the socialist city imagined? How did the enormous historical break in the construction of cities unfold? Yugoslav modernist architects welcomed the arrival of socialism as a chance to redress the ills of life in capitalism. As Nikola Dobrović wrote in 1946, the old capitalist Yugoslavia, with its speculative urban economy and impotent politics, could only produce a “degenerate urban physiognomy” for the benefit of the “financially powerful.”5 Such statements certainly echoed the dominant political discourse of the period, but they also strongly resonated with the modernist theories of urbanism, dating back to the earliest days of CIAM (Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne), which blamed capitalist speculation for the chaotic development of modern cities. Socialism, in turn, with its emphasis on comprehensive rational planning, promised a harmonious 5 6 1 2 3 4 Edvard Ravnikar, “Nova Gorica after 35 Years,” quoted in Vodopivec and Žnidaršič (2010), p. 333. Le Corbusier’s Preface in Grabrijan and Neidhardt (1957), p. 6. Illiteracy rate ranged from a single digit in Slovenia to over 40 percent in Macedonia. The Population of Yugoslavia (1974), p. 53. 7 8 9 Dobrović (January 1946); Dobrović (June 1946). The insistence on vehicular trafic was somewhat paradoxical, considering the minuscule number of private cars through the irst half of the socialist period. Scott (1998), p. 4. Brigitte Le Normand ofers a compelling account of these challenges in the case of Belgrade; Le Normand (2007). For the connection between the Black Wave and Yugoslav urbanization, see Kirn, Sekulić, Testen (2012). development of human settlements, in which the self-centered pursuit of minority interests at the expense of the whole would finally come to an end. In the mind of Dobrović and his colleagues, socialist politics and modernist architecture converged in the same goal: to harness the power of rational planning for the production of a new kind of harmonious and humane city. As a result, modernist principles of urban planning famously summarized in the Athens Charter—functional zoning, free-standing buildings in ample greenery, and the predominance of vehicular traffic—dominated city building during the formative years of the socialist period, as in much of postwar Europe. 6 These principles brought into existence whole new cities ex nihilo, subjecting the recently urbanized population to a new, rational, and healthy way of living, yet without much consideration of their habits, preferences, and social needs. City building in Yugoslavia was thus predestined to be a case of “seeing like a state,” to quote James C. Scott’s well-known definition of “high modernism” as the ultimate convergence of architectural and political goals: a “strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress… and, above all, the rational design of social order.”7 But what if the said state is not a fixed entity, but a work in progress that fluctuates and constantly evolves? What happens with the ideal visions of urban planners if the state itself starts cutting corners, facing the inability to fulfill its own hubristic promise of a “good life” for all? Challenges to the visions of Yugoslav planners came from both the governing elites for pragmatic short-term gains, and from the newly urbanized population, whose booming influx outpaced the official capacities of city building. 8 As a result, even the most important urban endeavors were compromised and some of their critical components remained unfinished. At the same time, large unregulated settlements sprang up at the edges of major cities, directly countering the ideal of harmoniously planned growth. The combined effects of these challenges ultimately led to a demise of modernist “blueprint planning,” which also coincided with the increasing scientization of the planning profession in the nineteen-seventies, influenced in part by regular collaborations with foreign experts. Some planners and architects, however, showed early on a sensibility for the specificities of local cultures and inherited environments. In response to complex conditions they encountered, they explored alternative, more complex approaches, often independently of or parallel to the post-CIAM theory developed in the West. On the one hand, the extensive war damage, as well as the subsequent natural disasters, required the reconstruction and improvement of the already well-defined neighborhoods, which could be treated neither as clean slate projects nor as small-scale patch ups. On the other, the rich surviving traditions of urban life were too powerful to ignore; combined with the rise of historic preservation, they emerged as values to be maintained and reinterpreted, rather than mercilessly eradicated (which, however, did not always save them from eradication). Such an approach was at first not necessarily in opposition to modernist principles, but rather worked as their extension or an internal critique. By the late nineteen-sixties, however, criticism of the anomie of new modernist neighborhoods, mounted simultaneously by sociologists and the public, thoroughly challenged modernist ideals, shifting the accent to such intangible values as historical continuity and “ambiance.” The internal critique from within the profession then further undermined them, signaling the rise of postmodernism. By the late nineteen-sixties, the dark underbelly of socialist urbanization acquired considerable visibility in the public. Unregulated urban developments and social pathology continued their long tradition, contradicting the promise of a just socialist society. Some social groups were left on the margins of progress, while others prospered thanks to everyone’s collective efforts. Sociologists studied these contradictions, journalists sensationalized them, and filmmakers used them as the raw material for a full-fledged movie genre known as the “Black Wave.”9 Yet, despite the unfulfilled promise of instan- 146 p. 146–47 Nikola Dobrović: Generalštab (Federal Ministry of Defense and Yugoslav People’s Army Headquarters), Belgrade, 1954–63. Damaged in 1999. 147 166 167 whole continent at the time went through massive state-sponsored social programs, yet realized in widely different political systems. 5 Similarly to many other European countries East and West, social collective housing in Yugoslavia was the most visible building type of the postwar urbanization, which took up much of architectural practice; but hundreds of thousands of individual family homes were also built with private funds, often aided by loans from banks and enterprises. Schools, hospitals, universities, and other institutions of “social standard”—as they used to be known—were all socially owned; yet collective workers’ or children’s resorts were increasingly replaced by hotels, which one chose according to individual preferences and financial means. The resulting “Yugoslav dream”—as historians have termed it after the fact—was a hybrid way of life that mixed collectivism and individualism in a characteristic blend: the systemic preference for socialized housing, but considerable consumerist freedom in equipping one’s home; free socialized health services, but individualized vacationing in a hotel on the Adriatic coast; free socialized education, but a thriving and diverse popular culture. Fulfilling that dream was not completely accessible to everyone; one of its paradoxes was that the more affluent classes —professionals and white-collar workers— were almost certain to acquire an affordable “social apartment,” and at the same time were able to spend their already higher disposable incomes on consumer goods and individual travel and entertainment. In contrast, the much more numerous blue-collar workers often had to expend their modest incomes on building their own houses, while spending their vacations in the more affordable collectivized resorts. Yet for broad segments of the population, regardless of their specific position in the system, the period between the late nineteen-fifties and the economic crisis of the nineteen-eighties is still remembered as a time of progress and upward mobility, which also created much of the existing architecture of everyday life. For all these reasons, one might argue, it is precisely in the sphere of everyday life that Yugoslavia was the most explicitly “socialist” and the most peculiarly “Yugoslav.” That was the context in which the largest body of architecture was built. Although building on a strong modernist tradition and limited by relatively strict material constraints, that architecture only briefly succumbed to the extreme utilitarianism stereotypically associated with socialism, and when it did, it was more due to poverty than for ideological reasons. Of course, most “everyday architecture” fell, at best, into the category of solid but unremarkable, repeating or adapting the models known from elsewhere; but certain clearly defined architectural cultures developed around the programs of everyday life—leisure, housing, the institutions of “social standard”—based on a considerable amount of research and innovation. These cultures took up an activist notion of design as a tool of social progress that mediates between collectivism and individual freedom, finding, for example, room for experiment in educational institutions and the spatial qualities of open plan in tight socialized apartments, or articulating the booming tourist industry to preserve the natural beauty and public access to the pristine Adriatic coast. Their particular success was in finding “Architecture” where one normally would not expect it—in mass housing or mass tourism—establishing a massive infrastructure of daily life that is still in use throughout the region. The generation that is alive right now and that is building a new society with its efforts must enjoy the fruits of its labor, not just some distant, future generations. Josip Broz Tito, n.d.1 The relationship between the collective well-being and individual freedom is at the core of all great ideologies of modern times. The term socialism encompasses a wide variety of ideas about that relationship, but the most commonly known version was deined in the “irst country of socialism,” the Soviet Union, by introducing a high level of vertical (hierarchical) collectivism. A centralized, planned, state-run economy and the socialized provision of housing, education, culture, leisure, and health services all resulted in relative uniformity in the everyday life; a long-term orientation towards heavy industry rather than consumer goods further added a sense of material scarcity. An extreme version of functionalism, applied in architecture under Nikita Khrushchev’s program to solve the housing crisis after Stalin’s death, hardly helped this image; it provided the irst opportunity of modern housing for millions of Soviet citizens, but at the price of monotonous residential neighborhoods consisting of enormous numbers of identical prefabricated buildings, spread across the country with little variation. Despite the great strides in economic development after World War II, the stereotype of monotony and austerity plagued everyday life in the Soviet Union—and in varied degrees the countries under its domination— virtually until its very end, becoming one of the most vulnerable spots in its confrontation with the West. The famous 1959 Kitchen Debate in Moscow between Khrushchev and the American Vice President Richard Nixon demonstrated how domesticity could be mobilized in a propaganda war; as architectural historian Greg Castillo has shown, homes thus became a major front on which the Cold War was fought and household appliances and objects of modern design were some of its key weapons. 2 Yugoslavia in many ways departed from the stereotype of socialist austerity. The Yugoslavs enjoyed greater affluence than their brethren in other socialist states, as well as the freedom to travel both East and West. Both were the products of a series of reforms that began after the break with Stalin in 1948, facilitating an experiment with the gradual liberalization and decentralization of economy, which included increasing levels of market competition, especially after the reforms of the mid-nineteen-sixties. The result was a well-developed consumer culture that in many ways resembled that found in the West—complete with a thriving advertising industry—sharing the same basic aspirations, only more modest and egalitarian. As the Yugoslavs eagerly learned to shop, spend, and travel, a new, large class of consumers came into being, generating, as historian Patrick Patterson argues, the first truly pan-Yugoslav identity, based on common consumer experiences. 3 At the same time, the state provided widespread social safety nets, as well as the first opportunities for education for the massive numbers of people, virtually eradicating the previously widespread illiteracy. For better or worse, much of the population was thus shielded from the direct effects of the fluctuating market and offered a chance of upward mobility and emancipation, even though socialism’s promise of guaranteed employment for all was far from fulfilled. 4 Those who could not find their place in the system were allowed to seek fortune abroad—typically in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, or France—further fueling the native thirst for consumerism by shipping Western goods back home. Daily life thus decisively shifted from radical, ascetic collectivization of the first postwar years towards a “Good Life” of greater individualism and affluence. Yet Yugoslavia was still a socialist state; on an imaginary scale between total collectivization and total individualism, it was somewhere in the middle, more collectivized than the West, but also more individualistic than the socialist East. A focused comparison not only with other socialist countries, but also with West European welfare states would, no doubt, be beneficial in determining Yugoslavia’s precise position of on that scale, since almost the 1 2 3 4 Quoted in Patterson (2012), p. 207. Castillo (2010). For an exhaustive study of Yugoslav consumer culture, see Patterson (2012). On the problem of unemployment in Yugoslavia, see Woodward (1995). 5 Sweden, as the most “socialized” among Western states, might be a good point of reference; see Mattson and Wallenstein (2010). Experiments in “Social Standard” The modernization of Yugoslavia included the construction of an extensive network of the institutions of “social standard,” predominantly educational, healthcare, culture, and sports facilities, from the local to the national level. pp. 164–65, 192–95 Such programs were included in the plans of all large, new neighborhoods, as well as in the existing settlements that lacked them. With their predominantly modernist language, these new facilities became deeply ingrained in the collective memory of the region as one of the defining images of modern life, participating in the citizens’ socialization from an early age. 176 in situ methods. The production ranged from utilitarian to inspired—Ivo Vitić’s Apartment building in Laginjina St. and Drago Galić’s reinterpretations of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation, both in Zagreb, were significant examples of the latter—but it was predominantly limited to one-off solutions or very small series. pp. 52, 199 The turning point occurred at the end of the decade, sparked in part by the push both in Belgrade and Zagreb to “cross the river Sava” and build new mass housing on virgin soil. In Zagreb, the architect Bogdan Budimirov in collaboration with Željko Solar and Dragutin Stilinović developed prefabricated systems YU60 and YU61 for the construction firm Jugomont, and used the latter on Novi Zagreb’s “housing blocks” (the Yugoslav equivalent to the microrayon: a housing neighborhood equipped with basic public services). 23 Based on large transversal concrete panels, YU61 featured elegant façades with orthogonal “neoplasticist” grids, filled in with reflective aluminum panels, which prompted the inhabitants to nickname the buildings “tins.” At the Institute for the Testing of Materials of Serbia (IMS) in Belgrade, the engineer Branko Žeželj developed from 1957 a prestressed skeletal system consisting of precast columns and slabs, which was widely used across Yugoslavia and also proved to be a successful export product, as it was used to build over 150,000 apartments across the world, from Hungary and Italy, to Cuba, Angola, and the Philippines. The major advantage of the IMS Žeželj system was its openness and a great deal of flexibility in designing both the building’s envelope and the interior partitions, thus practically allowing Le Corbusier’s “five points of architecture” to be put in practice in the context of collective social housing. The system’s freedom in organizing the façade is patently obvious in various neighboring blocks in central New Belgrade, all designed within less than fifteen years: from the smooth modernist chic of white mosaic tiles at Block 21, to the complex brutalist assembly at Block 23, to the exaggerated skeletal grid evoking traditional timber-frame construction at Block 19a. pp. 138 –39, 175, 200, 202 Besides the Jugomont and IMS systems, a host of other systems were used in Yugoslavia, either locally developed or imported from abroad, often involving some tinkering with the original technology in the process of its local application. 24 On top of that, the industrialized production was often hybridized with traditional labor-intensive technologies. In such instances, the structural core of the building was typically prefabricated and the rest built conventionally, thus partly undermining the very raison d’être of industrialization. Although less eficient, such an approach, in combination with the multiplicity of systems in use, resulted in highly diverse appearances; one might argue that it was a failure—the lack of central coordination and the need to improvise due to lacking technology—that inadvertently saved the country from the extreme monotony resulting from the consistently applied standardization and industrialization. pp. 98, 201–03 As an illustration, it is indicative that collective housing in Yugoslavia never became so closely identiied with its structural nature that it derived a name from it, as was the case elsewhere; there is thus no colloquial equivalent in the Yugoslav languages for the Czechoslovak panelák, the German Plattenbau, or the Hungarian panelház. Instead, individual apartment buildings were often nicknamed after certain formal characteristic or for their sheer size, for example: televizorka (TV set), named for its rounded windows resembling TV-screens, in New Belgrade; mamutica (mammoth), over 200 meters long and twenty stories high in Zagreb; and krstarica (cruise-ship), a massive mega-structure in Split 3. Another reason for the relative diversity of Yugoslav collective housing were the uncertain and changing standards. There were never standard apartment types devised to be built across the whole country, as was the case elsewhere. 25 With few exceptions, the replication of plans occurred only within the same housing block and each block was designed anew, often using a diferent system of prefabrication. Moreover, for each new project, the selected prefabricated system was customized to it the speciics of the architectural solution. Reasons were ultimately political: the lack of central power to impose one universal standard and the freedom of construction companies to act according to the requirements 177 1 2 Ilija Arnautović: Televizorka (TV set) apartment building, Block 28, New Belgrade, 1968–71. Frane Gotovac: Krstarica (cruise-ship) apartment building, Split 3, Split, 1971–73. 1 2 On Budimirov, see Mattioni (2007). We thank Jelica Jovanović, Jelena Grbić and Dragana Petrović for sharing some of their research; Jovanović, Grbić, Petrović (2011). 25 Compare, for example, the case of Czechoslovakia, where the architectural profession built onto a stronger industrial tradition to successfully implement typiication already in the nineteen-ifties; see Zarecor (2011), pp. 69–112, 224–94. 23 24 Jelica Jovanović and Tanja Conley, “Housing Architecture in Belgrade (1950-1980) and Its Expansion to the Left Bank of the River Sava,” in Mrduljaš and Kulić (2012), pp. 296-313 27 Ibid. 26 of the market. In an increasingly decentralized economy, a broad range of agents—investors and clients—entered into diverse partnerships, for example: state agencies in charge of coordinating the construction, socialist enterprises needing homes for their workers, or local communities inancing the “classic” social housing for the underprivileged. No wonder, then, that it was the powerful federal organ ization like the Yugoslav People’s Army that developed its own consistent standards, since it was suficiently large to have the inancial means and interest for investing in research. The resulting standards were not only quantitative, deining the minimum and maximum sizes of apartments and rooms, but also qualitative, prescribing the minimum requirements in the layout and equipment, thus putting an end to the previously common problems such as pass-through bedrooms or hard to organize kitchens. As the recent research by Jelica Jovanović and Tanja Conley indicates, the Army’s privileged standards soon leaked into civilian use and became a widely adopted common good. 26 It was under these unique conditions that an identifiable culture of residential design developed in Belgrade, resulting in the so-called Belgrade plan and a Belgrade school of residential architecture. The prime site for its emergence were at first the central blocks of New Belgrade, the design of which was determined at a series of public competitions, thus prompting the architects to follow and improve on each other’s solutions. These competitions brought to light a number of young architects and architectural teams specializing in residential design: Milenija and Darko Marušić; Božidar Janković, Branislav Karadžić i Aleksandar Stjepanović; Milan Lojanica, Borivoje Jovanović, and Predrag Cagić; Sofija Vujanac-Borovnica and Nedeljko Borovnica, and others. One of the key figures was Mihajlo Čanak, who founded the Center for Housing within the IMS Institute, thus bringing together the research in technology and housing culture, conducted in close collaboration with sociologists and other experts. 27 The result was a fast evolution in the quality and complexity of design methodology, which soon moved from standard modernist towers and slabs, partitioned apartments, and a complete separation of urban and architectural design, towards an integral design of the whole block (from the master plan down to street furniture), new typologies and concepts of urban space, and flexible, open apartments. 192 pp. 192–93 Marko Mušič: Cyril and Methodius University Complex, Skopje, 1974. 193 206 Josip Seissel (planning), Ivan Vitić (architecture), Zvonimir Fröchlich and Pavle Ungar (landscaping): Pioneers’ City (youth center), Zagreb, 1948. 207 Rikard Marasović: Children’s Health Resort, Krvavica near Makarska, 1961. 216 217 Architects in socialist Yugoslavia thus found themselves in a complex ideological space between the past and the future, simultaneously trying to navigate a convoluted history and to steer in the direction of a brighter future. The realistic approach under such conditions was to stay anchored in the present. Simply “catching up” with the “developed” world was already an enormous challenge, which in itself contained a good dose of futurism. Most architects were thus akin to drivers in the middle lane, advancing at a realistic speed, glancing from time to time at the rear-view mirror, and occasionally inding inspired shortcuts forward. Such driving was perfectly in line with the general course of modernization and yet it could not lead to all the practical and symbolic destinations that had to be visited. Accelerating beyond the available technological limits was more easily imagined than done, although not entirely out of reach; but it was still possible to wander of the curb, into the unpaved terrains of the past. It was on these uncharted detours from the steady course of modernization that some of the most original achievements were made. “How could we describe our reality if what is currently going on here happens nowhere else in the world, if everything here is infused with synchronous circles of six centuries: what emerges between the baroque, Morlachia, Turkish and Austrian small-towns—within the framework of a dramatic struggle with the Kremlin for internationalist principles of Leninism—are the contours of the twenty-second century!” Miroslav Krleža, 19521 The relationship toward historical time is a crucial question of modernity and of its cultural manifestations. Communism was by deinition a vanguard projection into the future; as such, it was supposed to be in natural alliance with cultural avant-gardes. But communist revolutions did not automatically lead to communism; instead, the resultant socialist states were understood as only transitional stages towards a future utopia. The relationship of their cultures to historical time was thus rendered far more ambiguous than a simple “light into the future.” Such ambiguity was established well before World War II: as the Russian architectural historian Vladimir Paperny theorized, the post-revolutionary Soviet Union developed two distinct cultures with opposed attitudes in regard to history. 2 According to the avant-garde view, the revolution was a new beginning; everything existing was supposed to be “burned down” and the architects had the task of imagining a brand new world from scratch. But the shift to socialist realism in the nineteen-thirties imposed an eschatological view in the opposite direction, proposing the revolution as an ending, or a culmination of civilization. As Stalinism indeinitely postponed the inal attainment of utopia, architects were expected to summarize all the “progressive” traditions of architectural history rather than to invent anything radically new. Socialism and its architecture thus by no means had to be aligned in their orientation to history; they could move at diferent speeds and even look in opposite directions. When Yugoslav architects encountered socialism in 1945, conflicting attitudes abounded. The state expected to impose the socialist realist “end of history,” but its efforts were compromised by the lack of official “gatekeepers” in the field of architecture. In contrast, modernists argued that, like every other epoch in history, socialism should strive to develop its own style; given the harsh material realities of the postwar situation, however, they could hardly afford to dream up any radical visions. Instead of emphasizing a complete reinvention of architecture, the profession argued for a moderately progressive approach, maintaining continuity with the socially engaged prewar modernism; as Sarajevo architect Mate Baylon wrote in 1946, “We are not starting from scratch—we are continuing with our work.”3 The break with the Soviet Union and the introduction of the system of self-management revived the status of Yugoslav socialism as a progressive project shaping the “contours of the twenty-second century.” Restating Marx’s call for a “ruthless critique of everything existing,” the conclusion of the 1958 Program of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia enthusiastically invited perpetual experimentation: “Nothing that has been created so far should be so sacred that it cannot be overcome, that it cannot be replaced with something more progressive, more liberated, and more humane.”4 But the accumulated layers of history still weighed down the leap into utopia: not only the weight of “backwardness,” which demanded decades to be skipped in order to achieve development, but also the varied identities of Yugoslavia’s constituent nationalities, which critically depended on history. Even more importantly, there was the massive weight of the recent war, from which the socialist project sprang, combining the revolution with antifascist liberation and the struggle against nationalist fratricide and thus conlating the basic legitimizing statements of the new state into an inseparable whole. It was a history of epic sufering and redemption against all odds, pitching Davids against Goliaths and good against evil—the stuf myths are made of. And myths were indeed made through the careful editing of the past, and relentlessly perpetuated through all modes of cultural production. 1 2 3 4 Krleža (1961), p. 189; translated by V.K. Paperny (2002), pp. 13–32. Baylon (1946). Program Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (1977), p. 259. 5 6 Berman (1982), p. 173. Rosen (2011). Looking Ahead One might expect that in a country like Yugoslavia—which attracted worldwide attention for its experiment of reinventing social relations for the sake of a more just, equitable world—architects would plunge into experimentation or utopian thinking without reservations. But that was hardly the case; for the most part, architecture in Yugoslavia was realistic, driven by pragmatic concerns. Instead of radical visions, there were evolutionary steps of adapting and retooling the existing modernist strategies. That was by no means a small feat: it meant that modernism was ultimately transformed from a “modernism of underdevelopment,” as Marshall Berman famously called it, into an agent of modernization. 5 It stopped being a “statement of intent” and became a tool of progress. Even if it was not always on the technological or aesthetic cutting edge, even when it was “moderate” or derivative, modernism came to stand for the actual realization of the promise of a better future; in a sense, most of this book is about that kind of futurism. It is unsurprising that the typical manifestations of space-age futurism, found both in the West and the Soviet Union, were not common in Yugoslavia, considering that the country was nowhere near partaking in the space technology. Still, a more radical merger of social critique and technological promise, like the one that lourished in the post-revolutionary Soviet Union, should have been imaginable. Indeed, it was local artists who were far more adventurous in those terms, as the Zagreb-based international movement of New Tendencies demonstrated by establishing one of the world’s irst hotbeds of computer art. 6 Rather than just a symptom of lingering conservatism, the relative scarcity of radical ideas in Yugoslav architecture may have been a result of the fact that the architectural profession was too busy with the very real project of modernization to waste the time with utopian considerations. By the time it inally became clear that fast modernization came at a price, the age of techno-utopias had already passed internationally and the critique, like everywhere else, materialized in its postmodernist form. The question of technological development was of key importance, since it determined the framework of the architects’ imagination. Material conditions at the end of World War II were miserable, greatly limiting the practical possibilities of construction. Among the rare examples of consciously progressive thought at that time—as well as precedents for future achievements—were the sports facilities that the Croatian architect Vladimir Turina designed in the late nineteen-forties for cities around Yugoslavia. His Dinamo Stadium in Zagreb—the only one of these realized—featured straightforward yet elegant stands in reinforced concrete, whose exposed supports evoked the structural poetic of Constructivism. But it was one of his unrealized projects that represented a singular achievement for its visionary quality: an aquatic center in Rijeka, a radical exploration of the concept of lexibility. The project envisioned a system of stands sliding on rails between the outdoor and indoor pools, the latter enveloped in an enormous cylindrical concrete shell. The pools could also be covered to serve as courts for other kinds of sport, even as airplane hangars. It was 224 225 1 Neven Šegvić: Project for the Museum of National Revolution, Rijeka, 1972–76 Sketch. 1 and maintains … a clear avant-garde character. At the root of his work is that very first avant-garde monument, created by Tatlin in 1921 for the Third International.”17 The same statement could be easily applied to the works of the sculptor Vojin Bakić, who indeed exhibited with the artists from the (neo-)avant-garde group EXAT 51 and the movement New Tendencies. pp. 250 –51 Finished in 1981, his memorial to a wartime partisan hospital atop Mt. Petrova Gora was the pinnacle of a systematic, decades-long search for monumental abstraction. It was one of the most architectural of the sculptor-designed memorials, enclosing a dramatic, fully inhabitable space with twelve interior levels that could be used as exhibition spaces. It was also among the last large-scale commemorative structures constructed before the collapse of the country, long after the “golden age” of commemoration had passed. Even in today’s seriously dilapidated state, the memorial’s “liquid” forms in stainless steel appear futuristic, despite the fact that in the meantime Frank Gehry made similar approach widely known. Besides monuments and memorials, which trailed between the disciplinary boundaries, sites of memory included certain properly architectural building types, such as the various memorial museums. A sizable subset of such institutions were the “museums of the revolution,” built in most large cities around the country. pp. 248–49, 262–63 Suspended between functional demands and the need for symbolism, most of these buildings—such as those in Sarajevo, Novi Sad, and Rijeka—were the versions of white modernist volumes with a certain expressive element occasionally added into the formula; the gravity-defying white volume of the Sarajevo museum achieved one of the most ethereal statements of that kind. But outside of large cities and in instances where the program demanded explicit commemoration, it was possible to explore more evocative strategies. In small towns or in open landscapes, it was relatively common to abstract the local vernacular architecture—typically houses and cabins with steep roofs—thus tying the revolution to the “people” and at the same time regionalizing modernist tropes. p. 244 On the other hand, buildings like the Memorial Museum Šumarice in Kragujevac, which commemorated a massive massacre of civilians by the German troops in 1941, aimed at empathy through an abstract spatial and tectonic coniguration. p. 246–47 Ivan Antić and Ivanka Raspopović designed it after their success with the Museum of Contemporary Art in New Belgrade, taking a step further in the exploration of group form by clustering brick shafts of varying heights. With no windows, lit only by the distant skylight at the top of each narrow shaft, the interior stirs the emotions by evoking a sense of claustrophobia and hopelessness, while still fulilling the pragmatic requirements of the program. 1 2 3 18 19 17 Argan (1981), pp. 7–8. Dušan Džamonja: Monument to the Revolution, Mrakovica, Mt. Kozara, 1972. Vojin Bakić: Monument to the Revolution of the People of Slavonia, Kamenska, 1958–68. Vojin Bakić: Memorial to the Revolution, Mali Petrovac, Mt. Petrova Gora, 1980–81, model. Curtis, Krušec, Vodopivec (2004). Ljiljana Blagojević makes a case for Bogdanović as a postmodernist: Blagojević (2011). 1 2 3 The sites of memory had quite varied destinies after the collapse of the socialist state. Some sufered amidst the attempts to reimagine the states that succeeded Yugoslavia by erasing the predecessor’s traces. Vojin Bakić fared particularly badly under such circumstances: besides Petrova Gora, which is still undergoing slow dismantling, his memorial at Kamenska—another dramatic form in stainless steel—was blown to pieces. Many others sites were damaged in the multiple wars of the nineteen-nineties. Most memorials, however, never lost their symbolic meaning and still continue their commemorative function. Some have been meticulously repaired and some have been even celebrated as pinnacles of the respective national cultures: Ravnikar’s cemetery at Kampor, for example, was presented as Slovenia’s entry at the Biennale of Architecture in Venice in 2004.18 Bogdan Bogdanović and the Mediation of Universal Memory Between his irst commission for the Monument to the Jewish Victims of Fascism in 1952 and the collapse of Yugoslavia forty years later, Bogdan Bogdanović (1922–2010) became the preeminent builder of memorials, eighteen in total scattered through ive of Yugoslavia’s six republics and in both autonomous provinces. Bogdanović’s signiicance, however, exceeded that of his built work; he was also a proliic author, an original architectural and urban theorist, a charismatic professor at the University of Belgrade with a cultish following, a master draughtsman, an active politician and one-time mayor of Belgrade, and a political dissident who went into exile because of his opposition to nationalism at the end of the socialist period. Bogdanović’s was also the most self-conscious attempt to mediate between past, present, and future and in many ways it anticipated and was closely afiliated with the rising post-modernism.19 But if his work should be labeled postmodern at all, it was a strain of postmodernism all its own: populist, but not commercial; in search of archetypes, but not typology; embracing ornament, but not favoring any particular “language”; and ultimately based on avant-garde methods, those of surrealism, a movement that otherwise had limited impact on architecture. Bogdanović was introduced to surrealism from an early age, through his father, a literary critic who was in close contact with the circle of Belgrade surrealists. As a student, the young Bogdan dreamed of designing “surrealist architecture,” for which he had no prec- 238 p. 238–39 Bogdan Bogdanović: Jasenovac Memorial Complex, Jasenovac, 1959–66. 239 242 p. 242–43 Bogdan Bogdanović: Partisans’ Cemetery, Mostar, 1959–65. 243 250 251 p. 250–51 Vojin Bakić and Berislav Šerbetić: Monument to the Partisans, Petrova Gora, 1979. BIOGRAPHIES Vladimir Kulić is an architectural historian and the co-editor of the forthcoming book Sanctioning Modernism: Architecture and the Making of Postwar Identities with Monica Penick and Timothy Parker. In 2009, he received the Bruno Zevi Prize for a Historical/Critical Essay in Architecture. He teaches at Florida Atlantic University. Maroje Mrduljaš is an architecture and design critic, curator, and author of several books, including Testing reality— Contemporary Croatian Architecture and Design and Independent Culture. He is the editor of Oris magazine and Head of the Research Library at the Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb. Wolfgang Thaler is based in Vienna and specializes in architectural photography. He has exhibited and published widely, in his own publications (Aida – Mit reiner Butter, Mep‘Yuk), as well as in collaborative projects, such as Das Fürstenzimmer von Schloss Velthurns, The Looshaus, and Vito Acconci: Building an Island. IMAGE CREDITS Archives Archive of Yugoslavia, Belgrade: 38/3, 41/1, 42/1–2, 43/1 Atlas of Croatian Architecture of the 20th and 21st Centuries, Zagreb: 181/4 CCN-Images, Zagreb: 38/2, 38/4, 47/1, 124/1-2, 126/3, 127/2, 136/1, 181/2–3, 182/2 IMS Institute, Center for Housing, Belgrade: 175/2, 177/1 Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb: 218/1 (Dunja Donassy-Bonačić), 220/3 Museum of the City of Zagreb, Zagreb: 26/1, 218/2–3 Oris: 23/1, 80/3, 81/1–2 State Archive of Croatia: 126/1 Ustanova France in Marta Ivanšek: 179/1–2 Private Collections: Courtesy Bakić Family Archive: 225/2 Courtesy Bogdan Bogdanović: 226/1–2 Courtesy Zoran Bojović: 48/1–2 Courtesy Robert Burghardt: 225/1 (photo Robert Burghardt) Courtesy Čičin Šain Family Archive: 181/1 Courtesy Aleksandar Janković: 39/4 Courtesy Miloš Jurišić: 26/2, 36/2, 38/1, 39/1–2, 82/1, 219/1 Courtesy Višnja Kukoč: 136/2 Courtesy Vladimir Mattioni: 175/1, 178/1 Courtesy Dejan Milivojević: 82/3–4 Courtesy Mihajlo Mitrović: 82/5 Courtesy Vesna Perković-Jović: 177/2 Courtesy private collection: 127/1 IMPRINT Courtesy Aleksandar Stjepanović: 175/3 Courtesy Elša Turkušić: 88/4, 132/2, 182/3 Courtesy Zlatko Ugljen and Nina Ademović Ugljen: 91/1–3 Photo Janez Kališnik: 86/3 Photo Nino Vranić: 86/2 Photo Vladimir Kulić: 24/3, 27/1–2, 36/1, 85/1, 222/1–2 Supported by Periodicals Arhitekt (Ljubljana): 171/1, 222/3 Arhitektura (Zagreb): 24/2, 34/1, 34/3, 34/4, 34/5, 43/2, 80/1–2, 123/1, 125/2, 131/2, 168/1-4, 171/2–3, 228/1 Arhitektura Urbanizam (Belgrade): 39/3, 82/2, 86/1, 125/1, 126/2 Čovjek i prostor (Zagreb): 129/1, 170/1, 182/1 Sinteza (Ljubljana): 170/2 Tehnika (Belgrade): 34/2 Other Publications Dubrović, Ervin: Ninoslav Kučan, exhibition catalog (Rijeka: Muzej grada Rijeke, 2006): 173/1 Grabrijan, Dušan, and Juraj Neidhardt, Arhitektura Bosne i put u suvremeno / Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity (Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije, 1957): 88/1–3, 132/1 Grimmer, Vera, ed., Neven Šegvić, special issue of Arhitektura (XLV, no. 211, 2002): 224/1 Grupa Meč, exhibition catalogue (Belgrade: Studentski kulturni centar, 1981): 228/2 Horvat-Pintarić, Vera, Vjenceslav Richter, (Zagreb: Graički Zavod Hrvatske): 1970, 43/3, 220/1–2 Katalog stanova JNA / 1 (Belgrade: Savezni sekretarijat za narodnu odbranu, 1988): 178/2 Krippner, Monica, Yugoslavia Invites (London: Hutchinson, 1954): 23/2, 24/1 Novi Beograd 1961 (Belgrade: Direkcija za izgradnju Novog Beograda, 1961): 123/2–3 Projekt spomenika na Petrovoj gori. (Zagreb: Acta architectonica, Zavod za arhitekturu Arhitektonskog fakuleteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu): 1981, 225/3 Skopje Resurgent: The Story of a United Nations Special Fund Town Planning Project (New York: United Nations, 1970): 45/1, 135/1–2 © 2012 by jovis Verlag GmbH and Vladimir Kulić, Maroje Mrduljaš, Wolfgang Thaler Texts by kind permission of the authors. Pictures by kind permission of the photographers/ holders of the picture rights. All rights reserved. Cover Wolfgang Thaler Goce Delčev Student Dormitory, Skopje, 1969 Map cartomedia (www.cartomedia-karlsruhe.de) Authors Vladimir Kulić, Maroje Mrduljaš, and Wolfgang Thaler All color photographs Wolfgang Thaler Graphic concept, layout and typesetting METAPHOR (www.metaphor.me) Type Memphis (Rudolf Wolf), Regular (Nik Thoenen) Printing and binding GRASPO CZ, a.s., Zlín Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Publisher jovis Verlag GmbH Kurfürstenstraße 15/16 10785 Berlin www.jovis.de ISBN 978-86859-147-7