258 Chu1>1('r 7 • !:h-mhnl

READING LONG

STORIES AND NOVELS

Brown 3

jC�!usion sunu

up main idea

1

without simply

ng1t

gardening had protected-or at least distracted-her from her loneliness,

isolation, and feelings of inadequacy. Finally, the theme emerges from our

understanding of this woman and the importance of her chrysanthemums.

Understanding Steinbeck's symbolism, therefore, is essential to understanding

how the story works.

The novel is the one bright book of !ife.

-D. H. LAWRENCE

MORE TOPICS FOR WRITING

1. Choose a story from this chapter. Describe your experience of reading that story, and

encountering its symbols. At what pomt did the main symbol's meaning beco me cleai

What in the story indicated the larger importance of that symbol?

2. From any story m this book, select an object, or place, or action chat seems clearly s•

bolic. How do you know? Now select an object, place, or action from the same story ti

clearly seems co signify no more than itself. How can you tell?

3. Analyze the symbolism in a story from "Stories for Further Reading." Some

choices might be "Dead Men's Pach," "The Story of an Hour," and "Where Are Y1

Going, Where Have You Been?" Choose a symbol that recurs over the course of rl

story, and look closely at each appearance it makes. How does the story's use of

symbol evolve?

4. In an essay of 600 to 800 words, compare and contrast the symbolic use of the scape1

in "The Lottery" and "The Ones Who Walk Away from Ornelas."

•

� TERMS FOR rev1e1v

Symbol ► A person, place, or thing in a narrative that suggests meanings beyond its lite1

sense. Symbol is related to allegory, but it works more complexly. A symbol often contai1

multiple meanings and associations.

Convrnlionul symbol ► A literary symbol that has a conventional or customary me:

ing for most readers-for example, a black cat crossing a path or a young bride in a whi1

dress.

Symholi(• ucl ► An action whose significance goes well beyond its literal meaning. In lit,

ature, symbolic acts often involve some conscious or unconscious ritual element such

rebirth, punfication, forgiveness, vengeance, or initiation.

Allegory ► A narrative in which the literal events (persons, places, and things) consistent!

point to a parallel sequence of symbolic equivalents. This narrative strategy is often used

dramame abstract ideas, historical events, religious systems, or political issues. An allegory

two levels of meaning: a literal level that tells a surface story and a symbolic level in which

abstract ideas unfold.

mong the forms of imaginative literature in our language, the novel has been

,the favorite of both writers and readers for more than two hundred years.

il!roadly defined, a novel is a book-length fictional story in prose, whose author tries

create the sense that while we read, we experience actual life.

This sense of actuality, also found in artful short stories, may be the quality that

the novel apart from other long prose narratives. Why do we not apply the

me novel to, for instance, Gulliver's Travels? In his marvel-filled account of Lemuel

iulliver's voyages among pygmies, giants, civilized horses, and noxious humanoid

ine, Jonathan Swift does not seem primarily to care if we find his story credible.

1ough he arrays the adventures of Gulliver in painstaking detail (and, ironically,

1as Gulliver swear to the truth of them), Swift neither attempts nor achieves a con• icing illusion of life. For his book is a fantastic satire that finds resemblances between

hie horses and man's reasoning faculties, between debased apes and man's kinship

ith the beasts.

1

1RIGINS OF THE NOVEL

lnlike other major literary forms-drama, lyric, ballad, and epic-the novel is a relaive newcomer. Originally, the drama in ancient Greece came alive only when actors

:rfonned it; the epic or heroic poem ( from the classic Iliad through the Old English

:If), only when a bard sang or chanted it. But the English novel came to maturity

literate times, in the eighteenth century, and by its nature was something different:

story to be communicated silently in printed books, at whatever moment and at

•hatever pace ( whether quickly or slowly and meditatively) the reader desired.

Some definitions of the novel would more strictly define the form. "The Novel is

picture of real life and manners, and of the time in which it was written," declared

:Iara Reeve in 1785. By so specifying that the novel depicts life in the present day,

1e critic was probably observing the derivation of the word novel. Akin to the

·ench word for "news" (nouvelles), it comes from the Italian nowlla ("something new

ind small"), a term applied to a newly made story taking place in recent times, and

!not a traditional story taking place long ago.

259

\0Vt'lis1ic Methods 261

260 C.hupccr 8 • Hr.ud111g Long !,10ri<''i ancl \owls

Romances

The novel, which is principally a realistic form, is often contrasted with the oth

. prose trad"

• the romance. In genera I terms, romance is a narrer.

maior

1t1on of narrative,

tive mode that employs exotic adventure and idealized emotion rather than reali t~

depiction of character and action. In the romantic mode-out of which most pop~l~~

genre fictions develop--people, actions, and events are depicted more as we wish

chem to be (heroes are very brave, villains are very bad) than as the complex entit'

they usually are. Medieval romances (in both prose and verse) presented chival~~s

t~les of kings, knights, and aristocratic ladies. Modem romances, emerging in t~~

nineteenth century, were represented by adventure novels such as Sir Walter Scott'

Ivanhoe which embodied the symbolic quests and idealized characters of earlies

chivalric tales in slightly more realistic terms, a tradition carried on in contempora~

popular works such as the Stars Wars and James Bond films.

Novels Versus Romances

Also drawing a line between novel and romance, Nathaniel Hawthorne, in his preface to The House of the Set1en Gables ( 1851), restricted the novel "not merely to the

possible, but to the probable and ordinary course of man's experience." A romance

had_no such limi~ations. Such a definition would deny the name of not1el to any fantastic or speculative story-to, say, the Gothic novel and the science fiction novel.

Carefully bestowed, the labels nooel and romance may be useful to distinguish

be_tw~en_ the true-to-life story

usual people in ordinary places (such as George

Eliot~ Silas Mamer o~ Amy Tans The Joy Luck Club) and the larger-than-life story

of darmg deeds and high adventure, set in the past or future or in some timeless land

(such as Walter Scott's Ivanhoe or J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lard of the Rings). This

sense of the actual is, perhaps, the hallmark of a novel, whether or not the events it

relates are literally possible.

A student shouldn't worry too much about the differences between the novel and

romance. In everyday conversation people usually refer to any book-length fictional

narratives as "novels." The important thing to remember is that there are two funda•

mentally different ways of telling a story. The novelistic method stresses the everyday,

realistic aspects. The romantic method stresses the aspects of adventure, surprise, and

wish fulfillment. It is particularly interesting to see the rare occasions when authors

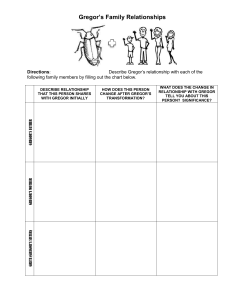

deliberately stray across the boundary between the two modes. In Franz Kafka's Tne

Metamorphosis, for example, the story begins with a fantastic premise-Gregor Samsa

wakes to discover himself turned into a giant insect. This bizarre transformation would

seem the very stuff of romance, but after the first sentence Kafka tells the story in the

most matter-of-fact and realistic way. The stunning quality of Kafka's masterpiece

comes from his novelistic manner of telling his seemingly unrealistic tale.

of

Novels and Journalism

Since both the novel and journalism try to capture the fabric of everyday life, there

has long been a close relationship between the two literary forms. Many novelists,

~mong them Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Crane, and Jack London, began their writ·

mg careers as cub reporters. Ambrose Bierce was the most influential newspaper

satirist of his day.

The two modes of writing, however, remain different. "Literature is the art of

writing something that will be read twice," commented critic and novelist Cyril

C nnolly, "journalism what will be grasped at once." Journalism greatly influences

h 0w novelists depict the world around them. Stephen Crane's "The Open Boat"

(~hapter 6) began as a newspaper accou~t of his ac~ual ex~eriex:ices in a small rowboat after the sinking of the Commodore m 1897. A 1oum~list might have been c~ncent with such a gripping first-person story of surviving a shipwreck, but a great ficuon

writer has the gift of turning personal bad luck into art, and Crane eventually created

a masterpiece of fiction based on fact.

NOVELISTIC METHODS

Many early novels were told in the form of letters. Sometimes these epistolary novels

contained letters by only one character; often they contained letters excha~ged by

several of the characters in the book. By casting his novel Pamela ( 1740) mto the

form of personal letters, Samuel Richardson helped give the story the appearance of

being not invented but discovered from real documents. Alice Walker's The Color

purple (1982) is a more recent epistolary novel, though some of the letters that tell

the scary are addressed to God.

Another method favored by novelists is to write as though setting down a memoir or an autobiography. Daniel Defoe, whose skill in feigning such memoirs was phenomenal, succeeded in writing the supposedly true confessions of a woman retired

from a life of crime, Moll Flanders ( 1722), and in maintaining a vivid truthfulness:

Going through Aldersgate Street, there was a pretty little child who had

been at a dancing-school, and was going home all alone: and my prompter,

like a true devil, set me upon this innocent creature. I talked to it, and it

prattled to me again, and I took it by the hand and led it along till I came to

a paved alley that goes into Bartholomew Close, and I led it in there. The

child said that was not its way home. I said, "Yes, my dear, it is; I'll show you

the way home." The child had a little necklace on of gold beads, and I had

my eye upon that, and in the dark of the alley I scooped, pretending to mend

the child's clog that was loose, and took off her necklace, and the child

never felt it, and so led the child on again. Here, I say, the devil put me

upon killing the child in the dark alley, that it might not cry, but the very

thought frighted me so that I was ready to drop down; but I turned the child

about and bade it go back again .... The last affair left no great concern

upon me, for as I did the poor child no harm, I only said to myself, 1 had

given the parents a just reproof for their negligence in leaving the poor little

lamb to come home by itself, and it would teach them to take more care of it

another time.

What could sound more like the voice of an experienced child-robber than this manner of excusing her crime, and even justifying it?

Some novelists place great emphasis on research and notetaking. James A.

Michener, the internationally best-selling author of novels such as Centennial

(which tracks life in Colorado from prehistory through modem times) and Chesapeake

(which describes 400 years of events on Maryland's Eastern Shore), started work on

a book by studying everything available about his chosen subject. He also traveled

to locations that might appear in the book, interviewed local people, and compiled

immense amounts of scientific, historical, and cultural data. Research alone, however,

262 ( hnptcr 8 ■ Hc11<li111, Long S1uri1•, und '\m ,·I,

is not enough to produce a novel. A novel grows to completion only through the

slow mental process of creation, selection, and arrangement. But raw facts can

sometimes provide a beginning. Many novels started when the author read some

arresting episode in a newspaper or magazine. Theodore Dreiser's impressive study of

a murder, An American Tragedy (l 925), for example, was inspired by a journalist's

account of a real-life case.

Nonfiction Novels

In the 1960s there was a great deal of talk about the nonfiction novel, in which the

author presents actual people and events in story form. The vogue of the nonfiction

novel was created by Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1966), which depicts an actual

multiple murder and the resulting trial in Kansas. Capote traveled to the scene of the

crime and interviewed all of the principal parties, including the murderers. Norman

Mailer wrote a similar novel, The Executioner's Song (1979), chronicling the life and

death of Gary Gilmore, the Utah murderer who demanded his own execution. More

recently, John Berendt's darkly comic 1994 account of the upper class and under class

of Savannah, Georgia, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (which also centers on

a murder and the subsequent trial), revived interest in the form.

Perhaps the name "nonfiction novel" (Capote's term for it) is newer than the

form. In the past, writers of autobiography have cast their memoirs into what looks

like novel form: Richard Wright in Black Boy (1945), William Burroughs in Junkie

( 1953 ). Derived from his reporting, John Hersey's Hiroshima ( 1946) reconstructs the

lives of six survivors of the atom bomb as if they were fictional. In reading such works

we may nearly forget we are reading literal truth, so well do the techniques of the

novel lend an air of immediacy to remembered facts.

Historical Novels

A familiar kind of fiction that claims a basis in fact is the historical novel, a detailed

reconstruction of life in another time, perhaps in another place. In some historical

novels the author attempts a faithful picture of daily life in another era, as does Rohen

Graves in l, Claudius (1934), a novel of patrician Rome. More often, history is a backdrop for an exciting story of love and heroic adventure. Nathaniel Hawthorne's Thi

Scarlet Letter (set in Puritan Boston) and Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage

(set on the battlefields of the Civil War) are historical novels in that their authors

lived considerably later than the scenes and events that they depicted, and strove for

truthfulness, by imaginative means.

Other Types of Novels

Other varieties of novel will be familiar to anyone who browses in bookstores: the

mystery or detective novel, che Western novel, the science fiction novel, and oth~r

enduring types. Novels are sometimes said to belong to a category if chey contain

some recognizable kind of structure or theme. Such a category is the Bildungsroman

(German for a "novel of growth and development"), sometimes called the apprenticeship

novel after its classic example, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1796) by Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe. This is the kind of novel in which a youth struggles toward

maturity, seeking, perhaps, some consistent worldview or philosophy of life. ~etimes the apprenticeship novel is evidently derived from the author's recollection

of his own early life: James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and

Tobias Wolff's Old School (2003).

Hcu,ling 1\ovels 16:1

Picaresques

In a picaresque (another famous category), a likable scoundrel wanders through

adventures, ltvmg by his wits, dupmg the straight citizenry. The name comes from

Spanish: p£caro, "rascal" or "rogue." The classic picaresque novel is the anonymous

Spanish Life of LawriUo de Tonnes (1554), imitated by many English writers, among

them Henry Fielding in his story of a London thief and racketeer, Jonathan Wild

(1743). Mark Twam's Huckleberry Finn (1885) owes something to the tradition; like

early picaresque novels, it 1s told in episodes rather than in one all-unifying plot and is

narrated in the first person by a hero at odds with respectable society ("dismal regular

and decent," Huck Finn calls it). In Twain's novel, however, the traveling swindlers

who claim to be a duke and a dauphin are much more typical rogues of picaresque

fiction than Huck himself, an honest innocent. Modem novels worthy of the name

include Saul Bellow's The Adventures of Augie March (1953), J. P. Donleavy's The

Ginger Man (1965), Erica Jong's Fanny (1981), and Seth Morgan's Homeboy (1990).

Short Novels and Novellas

The term short novel (or npvella) mainly describes the size of a narrative; 1t refers to

a narrative midway in length between a short story and a novel. (E. M. Forster once

said that a novel should be at least 50,000 words in length, and most editors and publishers would agree with that defimtion.) Generally a short novel, like a short story,

focuses on just one or two characters; but, unlike a short story, it has room to examine them in great depth and detail. A short novel also often explores its characters

over a greater period of time.

Many writers, such as Thomas Mann, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and Willa

Cather, favored the novella as a perfect medium between the necessary compression

of the short story and the potential sprawl of the novel. Franz Kafka's famous novella

The Metamorphosis is included in this book. When the term novelette 1s used, it usually refers (often disapprovingly) to a short novel written for a popular magazine,

especially m such fields as science fiction, romance, the Western, and horror.

READING NOVELS

Trying to perceive a novel as a whole, we may find it helpful to look for the same

elements that we have noticed in reading short stories. By asking ourselves leading

questions, we may be drawn more deeply into the novel's world, and may come to

recognize and appreciate the techniques of the novelist. Does the novel have themes,

or an overall theme? Who is its main character? What is the author's kind of narrative voice? How would we describe the tone, style, and use of irony? Why is this

novel written from one point of view rather than from another? If the novel in question is large and thickly populated, it may help to read it with a pencil and take brief

notes. Forced to put the novel aside and lacer return to it, we may find that the notes

refresh the memory. Once our reading of a novel is finished and we prepare co discuss

It or write about it, it may be a good idea to browse through it again, rereading brief

portions. This method of overall browsing may also help when first approaching a

bulky and difficult novel. Just as an explorer mapping unfamiliar territory may find it

~est to begin by taking an aerial view of it, so too the reader approaching an exceptionally thick and demanding novel may wish, at the start, to look for its general

shape. There is, of course, no shortcut to novel reading, and probably the best method

264 Chuptl'r 8 • lll'ucling Long Stori1:s nnd '\on-ls

1.,·o l'olsto~ 265

is to settle in comfort and read the book through: with your own eyes, not with the

borrowed glasses of literary criticism.

in Yasnaya Polyana, but frequently escaped to St. Petersburg and Western Europe. In

The Future of the Novel

was eventually undermined by the sex-obsessed and guilt-ridden Tolstoy, who engaged m

The death of the novel has been frequently announced. Competition from television, DVDs, video games, and the Internet, some critics claim, will overwhelm the

habit of reading; the public is lazy and will follow the easiest route available for entertainment. But in England and America television and films have been sending

people back in vast numbers to the books they dramatize. Jane Austen has never

lacked readers, but films such as Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Persuasion, and Sense and

Sensibility (not to mention Clueless, a teenage version of Emma set in Beverly Hills,

or Bride and Prejudice, a singing and dancing Bollywood treatment set in modem-day

India) made her one of the world's best-selling novelists. Stylish adaptations of Philip

K. Dick's offbeat science fiction, including Blade Runner, Tot.al Recall, and Minority

Report, have created a cult for his once neglected work. Sometimes Hollywood even

helps bring a good book into print. No one would publish Thomas M. Disch's sophisticated children's novella The Brave Little Toaster, until Walt Disney turned it into a

cartoon movie. A major publisher then not only rushed it into print, but commissioned a sequel.

Meanwhile, each year new novels by the hundreds continue to appear, their

authors wistfully looking for a public. Some of these books reach a mass audience. To

forecast the end of the novel seems risky, for the novel exercises the imagination of

the beholder. Ac any hour, at a touch of the hand, it opens and (with no warmup)

begins to speak. Once printed, it consumes no further energy. Often so small that it

may be carried in a pocket, it may yet survive by its ability to contain multitudes (a

"capacious vessel," Henry James called it): a thing chat is both a work of art and an

amazingly compact system for the storage and retrieval of imagined life.

many mfidelities (which were sometimes followed by the author's unsuccessful renunciations of sex). Despite its many problems . the marriage produced thirteen children. At

Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy wrote his two greatest novels, the six-volume War and Peace

( J863- 1869) , which depicts the lives of five aristocratic Russian families dunng the

Napoleonic Wars, and Anna Karenina ( 1877) , which tells the tTagic story of a woman led

try romantic illusions into a destructive adulterous liaison. As T olswy grew older, he became

obsessed with early Christianity. He formulated his own version of Christ's teachings,

stressing simplicity, love, nonviolence, and community property. Excommunicated by the

Orthodox Church, the count, who now dressed m peasant clothing, preached his "Chnstian

anarchism" to the Russian intelligentsia in streams of books and pamphlets. Upset by his

ruined maniage and his inability to renounce his personal wealth, the eighty-two-year-old

Tolstoy fled home one night to enter a monastery. He died of pneumonia a few days later in

a provincial railway station.

Tolstoy is one of the great masters of European Realism. His fame came early and

has never been seriously challenged. Much of his fiction examines a tTagic predicament of

human existence-the difficult search for truth and justice m a world of limited knowledge and

ethical imperfectlon. Tolstoy resolutely believed m the moral development of humanity, but

was also painfully aware of the obsracles to genuine progress. His gripping novella The Death

of Ivan Ilych dramatizes Tolstoy's centTal spiritual concerns. His antiheroic Everyman faces

death with the horrifying realization mat he has not lived a correct or meaningful life.

1862 he wed Sonya Bers, an intellectual middle-class woman. Initially happy, the marriage

Leo Tolstoy

The Death of Ivan Hych

188b

Translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude

The complex and contTadictory Leo Nikolaevich

Tolstoy ( 18 28-1910) is generally consuiered the

greatest Russian novelist. Born on his aristocratic

family's country estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in

centTal Russia, he was arphaned at nme and

raised by his aunts. At siXteen, Tolstoy entered

Kazan University to study law, but soon returned to the family estate. The young count

took off for St. Petersburg and Moscow, where

he led a profligate life-carefully listmg his moral

tTansgressions in his duiry. In 1851 Tolstoy

joined the army and fought in the Caucasus. It

was there that he completed his first book,

Childhood (185 2) , a lyrical memoir. Havmg

served in the Crimean War, he left the army in

1856 to become a writer.

For the next half century the brilliant and perpetually dissatisfied Tolstoy tried to settle

Leo Tolstoy

During an interval m the Melvinski trial in the large building of the Law Courts,

the members and public prosecutor met in Ivan Egorovich Shebek's private room,

where the conversation turned on the celebrated Krasovski case. Fedor Vasilievich

warmly maintained that it was not subject to their jurisdiction, Ivan Egorovich maintained the contrary, while Peter lvanovich, not having entered into the discussion at

the start, took no part in it but looked through the Gazette which had just been

handed m.

"Genclemen," he said, "Ivan Hych has died!"

"You don't say so!"

"Here, read it yourself," replied Peter lvanovich, handing Fedor Vasilievich the

paper still damp from the press. Surrounded by a black border were the words:

"Praskovya Fedorovna Golovina, with profound sorrow, informs relatives and friends

of the demise of her beloved husband Ivan llych Golovin, Member of the Coun of

Justice, which occurred on February the 4th of this year 1882. The funeral will take

place on Friday at one o'clock in the afternoon."

Ivan llych had been a colleague of the gentlemen present and was liked by chem

all. He had been ill for some weeks with an illness said to be incurable. His post had

been kept open for him, but there had been conjectures that in case of his death

Alexeev might receive his appomtment, and that either Vinnikov or Shtabel would

succeed Alexeev. So on receiving the news of Ivan llych's death the first thought of

each of the gentlemen in that pnvate room was of the changes and promotions it

might occasion among themselves or their acquaintances.

5

166 Chnplf'r 8 • Hf'uding Long S1nrir, and .\owls

I .I'<> I olstoy 267

"I shall be sure to get Shtabel's place or Vinnikov's " th h r••d

"I was promise

• d t h at 1ong ago, and the promot1'on me'

oug t re or Vas1·t·ievicL:

r

.

ans

an extra eigh h

11.:

ru bles a year ror me besides the allowance."

t undred

"Now I must apply for my brother-in-law's transfer from Kalu "

Ivanovic~. "My wife will be very glad, and then she won't be able fa, thought Peter

0

do anything for her relations."

say that I never

"I thought he would never leave his bed again ,, said p

I

. h

very sad."

'

ecer vanov1c aloud. "It•,

::Bue what really was the matter with him?"

The doctors couldn't say-at least they could b t

h f h

.

different. When last I saw him I thought he was gec't. u beac o,, t em sa,d something

"A d J h

,

mg etter.

n

aven t been to see him since the holidays I I

"Had he any property?"

• a ways meant to go."

::i

think his wife had a little-but something quite trifling."

.. We shall have to go to see her, but they live so terribly far away"

..~ar away frhom you, you mean. Everything's far away from your p.lace,,

ou see, e never can forgive my livin

h

h

.

•

P:ter lvanovich, smiling at Shebek. Then,

t:lki~t e; shde Jf the river," said

d1fferen~ parts of the city, they returned to the Court. g o t e !Stances between

Besides considerations as to the

'bl

f,

result from Ivan Ilych's death the me~:s;:ct eo;r:~s ers and promotions likely to

aroused, as usual, in all who h;ard of it the com I e de~th(·of a hnea~. a~quaintance

dead and not 1."

p acent ree mg t at It is he who is

;cJf

Each one thought or felt, "Well, he's dead but I'm aliv T"

. .

oi Ivan Ilych's acquaintances, his so-called friends, could n~~ h~~; ~~~ ~~re lft1m~te

c ey would now have to fulfil the very tiresome demands of

. m mg a sot_ at

the funeral service and paying a visit of cond I

h 'dpropr1ety by attending

F"·d V .

o ence to t e w1 ow

e or astlievich and Peter Ivanovich h d be h ·

•

.

Iv:movich had studied law with Ivan II h ad he~ is n~daresc ac~uamtances. Peter

obligations to him.

ye an a cons1 ered himself to be under

Having told his wife at dinner-time of Iv II h' d h

that it might be possible to get her b h an ye / eat and ~f hi_s conjecture

Ivanovich sacrificed his usual nap put o~o~i:re tra~s erreld hto thed1r circuit, Peter

Ilych's house.

'

venmg c ot es, an drove to Ivan

At the entrance stood a carr·

d

b Le .

hall downstairs near the cloak-sta~1::;a

ani~g ~g~i~st hthe wall in the

mented with gold cord and tassels h h

I co~ere Wit c ot of gold, omaTwo ladies in black were taking off t~e~~ fu:dc~:b 1;1tsheid up ":'ithh metal .powder.

of them as Ivan II h' •

b

• eter vanov1c recognized one

.

ye s sister, ut the other was a stranger to him H'

II

Sc h wartz was Just co • d

. b

• 1s co eague

and winked at him, :1~~0 ~:;~~;:~~ Ire inreingdPeter Ivanovic~ enter he stopped

and me."

ye as ma e a mess of thmgs-not like you

::~~}J·

Schwartz's face with his Piccadilly whiskers and his 5 Ii

Ii

.

.

~~~r:~t~:u:~:~:xao:;~!~nptiq:~::ynt which c?ntrastedd w:h ~:e;~ye~f:~g01r~

p

I

.

ere, or so it seeme to Peter Ivanovich

upstai:.erScha;~r::c~i~ll~:::;~ee l~!i:n t~ precede_ hi; and slowly followed them

Ivanovich understood that he wanted t

ut remame where he was, and Peter

evening. The ladies went upstairs to tho ai:r;ng~ where they should play bridge that

e wi ow s room, and Schwartz with seriously

compressed lips but a playful look in his eyes, indicated by a twist of his eyebrows the

m to the right where the body lay.

roo Peter Ivanov1ch, like everyone else on such occasions, entered feeling uncertain

hat he would have to do. All he knew was that at such times it 1s always safe to

w055 oneself. But he was not quite sure whether one should make obeisances while

d~ing so. He therefore adopt~d a middle course.

entering the room he _began

crossing himself and made a slight movement resembling a bow. Ac the same ttme, as

far as the motion of his head and arm allowed, he surveyed the room. Two young

men-apparently nephews, one of whom was a high-school pupil- were leaving the

room, crossing themselves as they did so. An old woman was standing motionless,

and a lady with strangely arched eyebrows was saying something to her in a whisper.

A vigorous, resolute Church Reader, in a frock-coat, was reading something in a

loud voice with an expression that precluded any contradiction. The butler's assiscant, Gerasim, stepping lightly in front of Peter Ivanovich, was strewing something

on the floor. Nottcing this, Peter lvanovich was immediately aware of a faint odor of a

decomposing body.

The last time he had called on Ivan llych, Peter lvanovich had seen Gerasim in

the study. Ivan llych had been particularly fond of him and he was performing the

duty of a sick nurse.

Peter lvanov1ch continued to make the sign of the cross, slightly inclining his

head in an intermediate direction between the coffin, the Reader, and the icons on

che table in a corner of the room. Afterwards, when 1t seemed co him that this movement of his arm in crossing himself had gone on too long, he stopped and began co

look at the corpse.

The dead man lay, as dead men always lie, in a specially heavy way, his rigid

limbs sunk m the soft cushions of the coffin, with the head forever bowed on the pillow. His yellow waxen brow with bald patches over his sunken temples was thrust up

in the way peculiar to the dead, the protruding nose seeming to press on the upper

lip. He was much changed and had grown even thinner since Peter Ivanovich had

last seen him, but, as is always che case with the dead, his face was handsomer and

above all more dignified than when he was alive. The expression on rhe face said chat

what was necessary had been accomplished, and accomplished rightly. Besides this

there was in that expression a reproach and a warning to the living. This warning

seemed to Peter lvanovich out of place, or at least not applicable to him. He felt a

certain discomfort and so he hurriedly crossed himself once more and turned and

went out the door-too hurriedly and too regardless of propriety, as he himself was

aware.

Schwartz was waiting for him in the adjoining room with legs spread wide apart

and both hands toying with his top-hat behind his back. The mere sight of that playful,

well-groomed, and elegant figure refreshed Peter lvanovich. He felt that Schwartz was

above all these happenings and would not surrender to any depressing influences. His

very look said that this incident of a church service for Ivan llych could not be a sufficient reason for infringing the order of the session-in other words, that it would certainly not prevent his unwrapping a new pack of cards and shuffling them that evening

while a footman placed four fresh candles on the table: in fact, that there was no reason

for supposing chat this incident would hinder their spending the evening agreeably.

Indeed he said this in a whisper as Peter lvanovich passed him, proposing that they

should meet for a game at Fedor Vas1lievich's. But apparently Peter lvanovich was not

destined to play bridge that evening. Praskovya Fedorovna (a short, fat woman who

°1:

25

168 Clinp1cr 8 • H,~adiug 1.oug S1ori1•~ und '\on·I,

despite all effons to the contrary had continued to broaden steadily from her should

downwards_ and who had ~he same extra~rdinarily arched eyebrows as the lady who.:

been standing by the coffin), dressed all m black, her head covered with lace, came 00

of her own roo": w,'.ch some ?ther_ ladies_, c~nduct~ them to the room where the dea~

body lay, and said: The service will begm 1rnrned1ately. Please go in."

-~hwar~z, _rna~in? an indefinite ~w, stood still, ev_i~ently neither accepting nor

declmmg this mv1~atton. P~kovya Fedoro~na,: recognmng Peter lvanovich, sighed,

went close up co him, took his hand, and said: I know you were a true friend to Iva

Ilych ..." and looked at him awaiting some suitable response. And Peter lvanovich

knew that, just as it had been the right thing to cross himself in that room, so what

he_ had to do he~e ~as to press her hand, sigh, and say, "Believe me...." So he did all

this and as he did 1t felt that the desired result had been achieved: chat both he and

she were touched.

"Corne with me. I want to speak co you before it begins," said the widow. "Give

me your arm."

Peter Ivanovich gave her his arm and they went to the inner rooms, passing

Schwartz, who winked at Peter lvanovich compassionately.

"That does for our bridge! Don't object if we find another player. Perhaps you

can cut in when you do escape," said his playful look.

.. Peter lvanovic~ sighed still more deeply and despondently, and Praskovya

Fedorovna pressed his arm gratefully. When they reached the drawing-room, upholstered in pink cretonne and lighted by a dim lamp, they sat down at the table-she

on a sofa and Peter lvanovich on a low pouffe, the springs of which yielded spasmodically under his weight. Praskovya Fedorovna had been on the point of warning him to take another seat, but felt that such a warning was out of keeping with

her present condition and so changed her mind. As he sat down on the pouffe

Peter lvanovich recalled how Ivan llych had arranged this room and had consulted

him regarding this pink cretonne with green leaves. The whole room was full of

furniture and knick-knacks, and on her way to the sofa the lace of the widow's

black shawl caught on the carved edge of the table. Peter Ivanovich rose to detach

it, and the springs of the pouffe, relieved of his weight, rose also and gave him a

push. The widow began detaching her shawl herself, and Peter lvanovich again sat

down, suppressing the rebellious springs of the pouffe under him. But the widow

had not quite freed herself and Peter lvanovich got up again, and again the pouffe

rebelled and even creaked. When this was all over she took out a clean cambric

handkerchief and began to weep. The episode with the shawl and the struggle with

the pouffe had cooled Peter lvanovich's emotions and he sat there with a sullen

look on his face. This awkward situation was interrupted by Sokolov, Ivan llych's

butler, who came to report that the plot in the cemetery that Praskovya Fedorovna

had chosen would cost two hundred rubles. She stopped weeping and, looking ac

Peter lvanovich with the air of a victim, remarked m French that it was very hard

for her. Peter lvanovich made a silent gesture signifying his full conviction chat it

must indeed be so.

"Please smoke," she said in a magnanimous yet crushed v01ce, and turned co

discuss with Sokolov the price of the plot for the grave.

Peter lvanovich while lighting his cigarette heard her inquiring very circumscan·

tially into the prices of different plots m the cemetery and finally decide which she

would take. When that was done she gave instructtons about engaging che choir.

Sokolov rhen left the room.

Leo l'ol, toy 269

"I look after everything myself," she cold Peter lvanovich, shifung the albums

chat lay on che cable; and noti_cing that the cab!~ was endan_gered .~Y his ~igar~tte•

ash, she immediately passed him an ashtray, saymg _as she did 5?: l cos:is1der 1t an

affectation to say that my grief ~revents my attending to _Practical a~a'.rs. ~ the

trary, if anything can- I wont say console me, but---d1stract me, 1t 1s seeing to

~~:rything concerning him." She again cook our her handkerchief as if preparing to

but suddenly, as if mastering her feeling, she shook herself and began to speak

cry,

· sorneth·mg I want to talk to you a bo~t."

calmly.

"Butthere 1s

.

Perer Ivanov1ch bowed, keeping control of the springs of the pouffe, which

immediately began quivering under him.

"He suffered terribly the last few days."

"Did he?" said Peter lvanovich.

"Oh, terribly! He screamed unceasmgly, not for minutes but for hours. For the

last three days he screamed incessantly. It was unendurable. 1cannot understand how

I bore it; you could hear him three rooms off. Oh, what I have suffered!"

"Is it possible that he was conscious all that time?" asked Peter lvanov1ch.

"Yes," she whispered. "To the last moment. He rook leave of us a quarter of an

hour before he died, and asked us to take Volodya away."

The thought of the suffering of this man he had known so inumately, first as a

merry little boy, then as a school-mace, and later as a grown-up colleague, suddenly

struck Peter lvanovich with horror, despite an unpleasant consciousness of his own

and this woman's dissimulation. He again saw that brow, and chat nose pressing

down on the hp, and felt afraid for himself.

"Three days of frightful suffering and then death! Why, that might suddenly, at

any time, happen co me," he thought, and for a moment felt terrified. Bue- he did

not himself know how- the customary reflection at once occurred co him that this

had happened co Ivan Hych and not to him, and that it should noc and could not

happen to him, and that to chink that it could would be yielding to depression which

he ought not co do, as Schwartz's expression plainly showed. After which reflecuon

Peter lvanovich felt reassured, and began to ask with interest about the details

of Ivan llych's death, as though death was an accident natural to Ivan Hych bur

certainly not co himself.

After many details of the really dreadful physical sufferings Ivan Hych had 45

endured (which details he learnt only from the effect those sufferings had produced

on Praskovya Fedorovna's nerves) the widow apparently found it necessary to get co

business.

"Oh, Peter lvanovich, how hard it is! How terribly, terribly hard!" and she again

began to weep.

Peter lvanovich sighed and waited for her to finish blowing her nose. When she

had done so he said, "Believe me ..." and she again began talking and brought out

what was evidently her chief concern with him-namely, to question him as to how

she could obtain a grant of money from the government on rhe occasion of her hus•

band's death. She made it appear chat she was asking Peter lvanovich's advice about

her pension, but he soon saw that she already knew about that to the minutest detail,

more even than he did himself. She knew how much could be got out of the govern·

ment in consequence of her husband's death, but wanted to find out whether she

could not possibly extract something more. Peter lvanovich tried to think of some

means of doing so, but after reflecting for a while and, out of propriety, condemning

the government for its niggardliness, he said he thought that nothing more could be

"°

Leo 'I ol~toy 271

got. Then she sighed and evidently began to devise means of getting rid of her visit

Noticing this, he put out his cigarette, rose, pressed her hand, and went out into

anteroom.

In the dining-room where the clock stood that Ivan llych had liked so mu h

and had bought at an antique shop, Peter lvanovich met a priest and a few acqua~tances who had come to attend the service, and he recognized Ivan llych's daughc

a handsome young woman. She was in black and her slim figure appeared slimm:;

than ever. She had a gloomy, decennined, almost angry expression, and bowed to

Peter lvanovich as though he were in some way to blame. Behind her, with the same

offended look, stood a wealthy young man, an examining magistrate, whom Peter

Ivanovich also knew and who was her fiance, as he had heard. He bowed mournfully

to them and was about to pass into the death-chamber, when from under the stair

appeared the figure of Ivan llych's schoolboy son, who was extremely like his fathe/

He seemed a little Ivan llych, such as Peter lvanovich remembered when they studied law cogeth~r. His tear-stained eyes had in them the look that is seen in the eyes

of boys of thirteen or fourteen who are not pure-minded. When he saw Peter

Ivanovich he scowled morosely and shamefacedly. Peter Ivanovich nodded to him

and entered the death-chamber. The service began: candles, groans, incense, tears.

and sobs. Peter lvanovich stood looking gloomily down at his feet. He did not look

once at the dead man, did not yield to any depressing influence, and was one of the

first to leave the room. There was no one in the anteroom, but Gerasim darted out

of the dead man's room, rummaged with his strong hands among the fur coats to find

Peter lvanovich's, and helped him on with it.

"Well, friend Gerasim," said Peter Ivanovich, so as to say something. "It's a sad

affair, isn't it?"

"It's God's will. We shall all come to it some day," said Gerasim, displaying his

teeth-the even, white teeth of a healthy peasant-and, like a man in the thick of

urgent work, he briskly opened the front door, called the coachman, helped Peter

lvanovich into the sledge, and sprang back to the porch as if in readiness for what he

had to do next.

Peter lvanovich found the fresh air particularly pleasant after the smell of

incense, the dead body, and carbolic acid.

"Where to, sir?" asked the coachman.

"It's not too late even now ... I'll call round on Fedor Vasilievich."

He accordingly drove there and found them just finishing the first rubber, so that

it was quite convenient for him to cut in.

ili~

II

Ivan llych's life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most

terrible.

He had been a member of the Court of Justice, and died at the age of forty-five. Hi.s

father had been an official who after serving in various ministries and departments m

Petersburg had made the sort of career which brings men to positions from which by

reason of their long service they cannot be dismissed, though they are obviously unfit

to hold any responsible position, and for whom therefore posts are specially created,

which, though fictitious, carry salaries of from six to ten thousand rubles that are n0t

fictitious, and in receipt of which they live on to a great age.

Such was the Privy Councillor and superfluous member of various superfluous

institutions, llya Epimovich Golovin.

}-{e had three sons, of whom Ivan Ilych was the second. The eldest son was following in his father's footsteps _only m _a nother _department, and was already

roaching that stage in the service at which a s1m1lar sinecure would be reached.

t e third son was a failure. He had ruined his prospects in a number of pos1ti?ns and

now serving m the railway department. His father and brothers, and sull more

: i r wives, not merely disliked meeting him, but avoided remembering his existence

less compelled to do so. His sister had roamed Baron Greff, a Petersburg official of

0

~:r father's type. Ivan Ilych was le phenix de la fam1Ue as people said. He was neither

as cold and fonnal as h,s elder brother nor as wild as the younger, but was a happy

an between them- an intelligent, polished, lively, and agreeable man. He had

::died with his younger brother at the School of Law, but the latter had failed to

complete the course and was expelled when he was in the fifth class. Ivan Hych finished the course well. Even when he was at the School of Law he was JU~t what he

mamed for the rest of his life: a capable, cheerful, good-natured, and sociable man,

;ough smct in the fulfillment of what he considered to be his duty: and he considered his duty to be what was so considered by those in authority. Neither as a boy nor

as a man was he a toady, but from early youth was by nacure attracted to people of

high scauon as a fly is drawn to the light, assimilating their ways and views of life and

establishing friendly relations with them. All the enthus1asms of childhood and

youth passed without leavmg much trace on him; he _succumbed to se1:15u_ality, ~o

vanity, and latterly among the highest classes to liberalism, but always w1thm limits

which his insunct unfailingly md1cated to him as correct.

At school he had done thmgs which had fonnerly seemed to him very horrid and

made him feel disgusted with himself when he did chem; but when later on he saw

chat such acuons were done by people of good position and that they did not regard

them as wrong, he was able not exactly to regard them as right, but to forget about

them enurely or not be at all troubled at remembering them.

Having graduated from the School of Law and qualified for the tenth rank of the 60

civil service, and havmg received money from his father for his equipment, Ivan

Ilych ordered himself clothes at Schanner's, the fashionable tailor, hung a medallion

inscribed respice finem 0 on his watch-chain, took leave of his professor and the prince

who was patron of the school, had a farewell dinner with his comrades at Donon's

first-class restaurant, and with his new and fashionable portmanteau, linen, clothes,

,having and other toilet appliances, and a traveling rug all purchased at the best

shops, he set off for one of the provinces where through his father's influence, he had

been attached to the Governor as an official for special service.

In the province Ivan llych soon arranged as easy and agreeable a position for

himself as he had had at the School of Law. He performed his official tasks, made his

career, and at the same time amused himself pleasantly and decorously. Occasionally

he paid official visits to country districts, where he behaved with dignity both to his

superiors and inferiors, and performed the duties entrusted to him, which related

chiefly to the sectarians,0 with an exactness and incorruptible honesty of which he

could not but feel proud.

In official matters, despite his youth and taste for frivolous gaiety, he was

exceedingly reserved, punctilious, and even severe; but in society he was often amusing

~ p/lbl,x de la famille: French for "the prize of the family." respice fincm: Latin for ~Think of the

end (of your life)." sectarians: dissenters from the Orthodox Church.

272 Chapter 8 • H,•mling Loug Storw, unrl \owls

and witty, and always good-natured• correcc •m h.1s manner and bon

G ovemor and h is wife-with whom he was )·k

f h' c

en/ant 0

him.

a e one o t e iamily-1.1.Sed ;o

In the province he had an affair with a lad wh

young lawyer, and there was also a milliner and ~ere o made advances to the e

who "s"t d h d· .

'

were carousals with .d

v1 I e t e istnct, and after-supper visits to a

•

I.

a1 es-de

reputation; and there was too some obse uiousn;ercam ~ut Y•~g street of dou

chief's wife, but all this was done with su~h a ton:o}o ~ ~h1ef _and even to

names could be applied to it. It all came under h

~

reeding that no

faut que jeunesse se passe."o It was all done wit~ :t:~dhg ~f t~e French saying:

French phrases, and above all among peo le of th

an ~• m clean linen,

with the approval of people of rank.

p

e best society and consequ

So Ivan Hych served for five years and then came

h

. .

Th~ ~e~ and reformed judicial institutions were intr~~c:;ge '~ his official

nee e . van Hych became such a new man H

ffi

' an new men

magistrate, and he accepted it though th

• e w~s o ered the post of exam,

him to give up the connections he had ;o::tdwas~n anoter province and obi

met to give him a send-off they had

e an to ma e new ones. His fr,

with a silver cigarette-case 'and he set ~/rouhp_-photograph taken and presented

A

. .

'

to ts new post.

5 exammmg magistrate Ivan Hych was •

.

man, inspiring general res t and c bl

Just as ~omm~ I1fauto and decorous

private life, as he had bee~hen a_pa e of seffp~".1tmg has official duties from h

actmg as an o ictal on special

• H

now as examining magistrate were far more .

.

service. is dut"

his former position it had been I

mterestmg and attractive than before. I

Sch

d

peasant to wear an undress

•f,

d

armer, an to pass through the crowd of ti .

. . uni orm ma e br

rously awaiting an audience with the G

pe t1odnerhs and off1c1als who were timo. h

ovemor an w o envied h·

• h fr

easy gait e went straight into his chief . '

im as wit ee and

. h h·

s pnvate room to have a c

f

d

arette Wit am. But not many people h d h be d"

up o tea an a cig1 er• . I

a t en en 1rectly depende

h"

po ace 01, acta s and the sectarians when he

.

.

nt on Lm-only

treat them politely, almost as comrades a v.:;~c on speftal_missions-and he liked to

had the power to crush them was treatin s :h e ~er~_eu_mg them feel that he who

were then but few such people. But now ; em m ~ i_s s1mpl~, friendly way. There

that everyone without exception e

'h s an ex~mmmg magistrate, Ivan Hych felt

his power, and that he need only 'wr~~n tf, e mos~1mportant and self-satisfied, was in

heading, and this or that important sel; e~ ;~r s on a sheet of paper with a certain

in the role of an accused person or~ . -saus e person would be brought before ham

sit down, would have to stand bef, wh1~ess,dand if he did not choose to allow him to

ore 1m an answer his q

•

I

II

ab used his power; he tried on the co t

uest1ons. van ych never

ness of it and of the possibility of s:rt ra': t~ soften its expr~ssion, but the consciousattraction of his office. In his work its:iT~g its_e~e~t, s~pphed _the _chief interest and

acquired a method of eliminating all co,nsi~ec1a_ y m_has exammauons, he very soon

the case, and reducing even the most

. erataons irrelevant to the legal aspect of

presented on paper only in its extem~~:~~:tfd case to a f~rm i~ which it would be

of the matter, while above all ob

.

P etely excluding his personal opinion

new and Ivan Ilych was one of th/~rv;ng every pre!scribed formality. The work was

rs men to app y the new Code of 1864.o

bon enfanr: French for "a well-behaved child" "II fi

.

comme ilfaut: "as required" rule-abidi

C~

auc que}eUnesse se passe": "Youth doesn't last."

followed by a thorough all:round refor~~f j d· io{ 1864:_;he emancipation of the serfs in 1861 was

u •ca procecutngs. [Translators' note.]

I .,•o 1 ols1o, 17:l

On taking up the post of examinmg ~agistrate in a new t_own, he made new

. ranees and connections, placed himself on a new fooung, and assumed a

31~at different cone. He took up an attitude of rather dignified aloofness

~s the provincial authorities, but picked out the best circle of legal gentlemen

ealthY gentry living in the town and assumed a tone of slight dissatisfaction

:he government, of moderate liberalism, and of enlightened citizenship. At the

e time, without at all altering the elegance of his toilet, he ceased shaving his

and allowed his beard to grow as 1t pleased.

Ivan llych settled down very pleasantly in this new town. The society there,

ich inclined cowards op~ition to the Governor, was fnendly, hts salary was

r, and he began to play vmt, 0 which he found added not a lmle to the pleasure of

for he had a capacity for cards, played good-humoredly, and calculated rapidly

'astutely, so that he usually won.

After living there for two years he met his future wife, Praskovya Fedorovna

,khel, who was the most attractive, clever, and bnlliant girl of the set in which he

ved, and among other amusements and relaxations from h is labors as examining

agistrate, Ivan Ilych established light and playful relauons with her.

While he had been an official on special service he had been accustomed to

nee, but now as an examining magistrate it was exceptional for him to do so. If he

need now, he did it as if to show that though he served under the reformed order of

things, and had reached the fifth official rank, yet when it came to dancing he could

do it better than most people. So at the end of an evening he sometimes danced with

Praskovya Fedorovna, and it was chiefly durmg these dances that he captivated her.

She fell in love with h,m. Ivan Hych had at first no definite intention of marrying,

but when the girl fell m love with him he said to himself: "Really, why shouldn't I

marryr'

Praskovya Fedorovna came of a good family, was not bad-lookmg, and had some 70

little property. Ivan llych might have aspired to a more brilliant match, but even this

was good. He had his salary, and she, he hoped, would have an equal income. She

was well connected, and was a sweet, pretty, and thoroughly correct young woman .

To say that Ivan Hych married because he fell in love with Praskovya Fedorovna and

found that she sympathized with hts views of life would be as incorrect as to say that

he married because his social circle approved of the match. He was swayed by both

these considerations: the marriage gave him personal satisfaction, and at the same

time it was considered the right thing by the most highly placed of his associates.

So Ivan Hych got married.

The preparauons for marriage and the beginning of married life, with its conjugal caresses, the new furniture, new crockery, and new linen, were very pleasant until

his wife became pregnant-so that Ivan llych had begun to think that marriage

would not impair the easy, agreeable, gay, and always decorous character of h is life,

approved of by society and regarded by himself as natural, but would even improve it.

But from the first months of his wife's pregnancy, something new, unpleasant,

depressing, and unseemly, and from which there was no way of escape, unexpectedly

showed itself.

His wife, without any reason--de gaiete de coeur0 as Ivan llych expressed it co

himself-began to disturb the pleasure and propriety of their life. She began to be

1,m1: a form of bridge. !Translators' note.]

de gaieti de coeur: "from pure whim."

274 C,hnp1rr 8 • lll'11<li11g Long Stori•c~ und '\on·l,

jealous without any cause, expected him to devote his whole attention to her f,

fault with everything, and made coarse and ill-mannered scenes.

' oU

At first Ivan Hych hoped to escape from the unpleasantness of this state of affa·

by the same easy and decorous relation to life that had served him hereto£, . 111

tried to ignore his wife's disagreeable moods, continued to live in his usual e~;e· ht

pleasant way, invited friends to his house for a game of cards, and also tried goi y

~o his_club or_spending hi~ evenings with friends. But one day his wife began up~~~:

mg him so vigorously, usmg such coarse words, and continued to abuse him

time he did not fulfil her demands, so resolutely and with such evident determinev_ery

not to give way till he submitted-that is, till he stayed at home and was bored . ation

1USt;&a

s he was-that he became alarmed. He now realized that matrimony-at an

with Praskovya Fedorovna-was not always conducive to the pleasures and ameYn_~te

•r

.

.

ltles

of lue, but on the contrary often mfrmged both comfort and propriety, and that h

must therefore entre~ch hims~lf ag~i_n st su~h infringement. And Ivan Ilych began t:

seek for m~ns of domg so. Hts offk1al ~uttes_were the one thing that imposed upon

Praskovya Fedorovna, and by means of his official work and the duties attached to ·

he began struggling with his wife to secure his own independence.

tt

With the birth of their child, the attempts to feed it and the various failures in

doing so, ~nd with the real and imaginary illnesses of mother and child, in which

Ivan llych s s'.mpathy _was demanded but about which he understood nothing, the

need of securing for himself an existence outside his family life became still more

imperative.

As his wife grew more irritable and exacting and Ivan llych transferred the

center of gravity of his life more and more to his official work, so did he grow to like

his work better and became more ambitious than before.

Very soon, within a year of his wedding, Ivan Hych had realized that marriage,

though 1t may add some comforts to life, is in fact a very intricate and difficult affair

towards which in order to perform one's duty, that is, to lead a decorous life approved

of by society, one must adopt a definite attitude just as towards one's official duties.

And Ivan Hych evolved such an attitude towards married life. He only required of

it those conveniences-dinner at home, housewife, and bed-which it could give

him, and above all that propriety of external forms required by public opinion. For

the rest he looked for light-hearted pleasure and propriety, and was very thankful

when he found them, but if he met with antagonism and querulousness he at once re•

tired into his separate fenced-off world of official duties, where he found satisfaction.

Ivan llych was esteemed a good official, and after three years was made Assistant

Public Prosecutor. His new duties, their importance, the possibility of indicting and

imprisoning anyone he chose, the publicity his speeches received, and the success he

had in all these things, made his work still more attractive.

More children came. His wife became more and more querulous and ill-tempered,

but the attitude Ivan Hych had adopted towards his home life rendered him almost

impervious to her grumbling.

After seven years' service in that town he was transferred to another province as

Public Prosecutor. They moved, but were short of money and his wife did not like the

place they moved to. Though the salary was higher the cost of living was greater,

besides which two of their children died and family life became still more unpleasant

for him.

Praskovya Fedorovna blamed her husband for every inconvenience they encoun·

tered in their new home. Most of the conversations between husband and wife,

•ally as to the children's education, led to topics which recalled former dis•

especi and those disputes were apt to flare up again at any moment. There remained

pur•hose rare periods of amorousness which still came to them at times but did not

on yl:ng. These were islets at which they anchored for a while and then again set

last pon that ocean of veiled hostility which showed itself in their aloofness from

out unother. This aloofness might have grieved Ivan Hych had he considered that it

one;t not to exist, but he now regarded the position as normal, and even made it

ohug al at which he aimed in family life. His aim was to free himself more and more

t ego

d

from those unpleasantnesses and to give them a sem?lance_ of h~rml~ness an pro.

He attained this by spending less and less ttme with his family, and when

priety.

· to safeguard his position

· · by th e presence of outs1'd ers.

bl' ed to be at home he tned

Th:gchief thing, however, was that he had his official ~uties. The whole in_terest of

h' life now centered in the official world and that interest absorbed him. The

ts sciousness of his power, being able to ruin anybody he wished to ruin, the

con

.

• h h·1s

importance, even the external d igrtity o f h is e_ntry _into court, or meetm~s

wit

subordinates, his success with superiors and mfenors, and above all his masterly

handling of cases, of which he was conscious-all this gave him pleasure and filled

his life, together with chats with his colleagues, dinners, and bridge. So that on the

whole Ivan llych's life continued to flow as he considered it should do-pleasantly

and properly.

.

So things continued for another seven years. His eldest daughter was already six•

teen another child had died, and only one son was left, a schoolboy and a subject of

diss;nsion. Ivan llych wanted to put him in the School of Law, but to spite him

Praskovya Fedorovna entered him at the High School. The daughter had been

educated at home and had turned out well: the boy did not learn badly either.

Ill

So Ivan !lych lived for seventeen years after his marriage. He was already a Public Prosecutor of long standing, and had declined several proposed transfers while

awaiting a more desirable post, when an unanticipated and unpleasant occurrence

quite upset the peaceful course of his life. He was expecting to be offered the post of

presiding judge in a University town, but Happe somehow came to the front and

obtained the appointment instead. Ivan Hych became irritable, reproached Happe,

and quarreled both with him and with his immediate superiors-who became colder

to him and again passed him over when other appointments were made.

This was in 1880, the hardest year of Ivan Ilych's life. It was then that it became 85

evident on the one hand that his salary was insufficient for chem to live on, and on

the other that he had been forgotten, and not only this, but that what was for him

the greatest and most cruel injustice appeared to others a quite ordinary occurrence.

Even his father did not consider it his duty to help him. Ivan llych felt himself aban•

cloned by everyone, and that they regarded his position with a salary of 3,500 rubles

as quite normal and even fortunate. He alone knew that with the consciousness of

the injustices done him, with his wife's incessant nagging, and with the debts he had

contracted by living beyond his means, his position was far from nonnal.

In order to save money that summer he obtained leave of absence and went with

his wife to live in the country at her brother's place.

In the country, without his work, he experienced ennui for the first time in his

life, and not only ennui but intolerable depression, and he decided chat it was impos•

sible to go on living like that, and that it was necessary to take energetic measures.

276 Cho1,11·r 8 • Rru,ling Loni: Srori,·, nnd \owl~

1-Nt l'ol~to~ 277

Having passed a sleepless night pacing up and down th

go to Petersburg and bestir himself in order to

. h h e vheranda, he deci

.

h·

d

'

punts t ose w O had r •1 d

C•ate im an to get transferred to another ministry.

,a1 e to a

Next day, despite many protests from his ·£,

d h

Petersburg with the sole object of obtaining a pos;~~t~: sal:r ~~~~er, he staned

a year. He was no longer bent on any particular d

ry

e thousand ru

activity. All he now wanted was an a

.

epartment, or tendency, or k'

h

d

ppomtment to another post • h

t fohusan rubles, either in the administration, in the banks • h ~t ~ salary of

o t e Empress Marya's Institutions o o

. h

, wit

e railways in

.

I

ffi

' r even mt e customs-but "th d

'

it a sa ary o ve thousand rubles and be •

. .

h

I

a to carry

had failed to appreciate him.

m a mtn1Stry ot er than that in which t

And this quest of Ivan Hych 's was crowned with rema k bl

cess. At Kursk an acquaintance of his F I II .

. r ~ e and unexpected

down beside Ivan llych, and told him ~f~ ~et:'~!~t mto t _e first-class carriage,

Kursk announcing that a change was about ~o Just recet~ed by the Governor

lvanov1ch was to be superseded by Ivan Semenovi~~~e place m the ministry: p

The proposed change, apart from its si in

fi R .

Cance for Ivan llych, because by brin .

cance or ussia, had a special sign•

consequently his friend Zachar lvani•~gh o~ward a new man, Peter Petrovich a

since Zachar lvanovich was a friend an~•~ it it was fhhi~hly favorable for Ivan 1iyc

J M

h

o eague o 1s

n oscow t is news was confirmed

d

·h·

found Zachar lvanovich and received a d~J~it/n rea_c mg Petersb~rg Ivan lly

former department of Justice.

promise of an appointment in h

r

': week later he telegraphed to his wife: "Zachar in Mill '

appointment on presentation of report."

er s place. I shall receiv

Thanks to this change of personnel Ivan II h h d

appointment in his former ministry whi~h lacerh. a unexpectedly obt~ined

colleagues besides giving him five tho

~

tm two stages above his fonner

hundred rubles for expenses connected us~~ ~~bles salary and three thousand five

his former enemies and the whole d

wit is _rhmoval. All his ill humor towards

happy.

epartment vams ed, and Ivan Ilych was completely

He returned to the country more cheerful a d

long time. Praskovya Fedorovna also h

n contented than he had been for a

them. Ivan Hych told of how he had ~e:e~~d ?band a truce ~as arranged between

those who had been his enemies were

ete y everybody m Petersburg, how all

envious they were of his appointment pu~ t~ shame hand now fawned on him, how

liked him.

' an ow muc everybody in Petersburg had

Praskovya Fedorovna listened to all this and

.

.

contradict anything, but only made lans for h a_pp~ar~ to believe it. She did not

were going. Ivan Hych saw with delight h ht e1r lltfe m the town to which they

his wife agreed, and that, after a stumbl: ~it ~ p ans w~r~ his_plans, that he and

character of pleasant lightheartedness and' de~~~~was regammg Its due and natural

Ivan Hych had come back for a short ti

j

duties on the 10th of Septembe M

me on Y, for he had to take up his new

~lace, to move all his belonging/fro::~~ve;, ~e needed time to settle into the new

uonal things: in a word to make

h p ovmce, and to buy and order many addiwere almost exactly wha~ Praskov su;..darrangemenhts as he had resolved on, which

ya e orovna too ad decided on.

Empress Marya's lrutitucions: orphanages.

N w that everything had happened so fortunately, and that he and his wife were

~n their aims and moreover saw so little of one another, they got on together

one t~an they had done smce the first years of marriage. Ivan Hych had thought of

ter htS family away with him at once, but the insistence of his wife's brother and

'~ter-in-law, who had suddenly become particularly amiable and friendly to him

his family, induced him to depart alone.

So he departed, and the cheerful state of mind induced by his success and by the

ony between his wife and himself, the one intensifying the other, did not leave

. He found a delightful house, just the thing both he and his wife had dreamt of.

acious, lofty reception rooms in the old style, a con~eniem and dignified stu~y,

for his wife and daughter, a study for his son-it might have been specially built

them- Ivan Hych himself superintended the arrangements, chose the wallpapers,

r lemented the furniture {preferably with antiques which he considered particularly

me j[ faut), and supervised the upholstenng. Everything progressed and progressed

approached the ideal he had set himself: even when things were only half com•

eted they exceeded his expectations. He saw what a refined and elegant character,

e from vulgarity, it would all have when it was ready. On fallmg asleep he pictured to

imself how the reception-room would look. Looking at the yet unfinished drawing,

room he could see the fireplace, the screen, the what-not, the little chairs dotted here

and there, the dishes and plates on the walls, and the bronzes, as they would be when

rverything was in place. He was pleased by the thought of how his wife and daughter,

who shared his taste in this matter, would be impressed by it. They were certainly not

expecting as much. He had been particularly successful m finding, and buying cheaply,

antiques which gave a particularly anstocratic character to the whole place. But in his

letters he intentionally understated everything in order to be able to surpnse them. All

this so absorbed him that his new duties-though he liked his official work-interested

him less than he had expected. Sometimes he even had moments of absentmindedness

during the Court Sessions, and would consider whether he should have straight or

curved cornices for his curtains. He was so interested in it all that he often did things

himself, rearranging the furniture, or rehanging the curtains. Once when mounting a

stepladder to show the upholsterer, who did not understand, how he wanted the hang•

ings draped, he made a false step and slipped, but being a strong and agile man he clung

on and only knocked his side against the knob of the window frame. The bruised place

was painful but the pain soon passed, and he felt particularly bright and well just then.

He wrote: "I feel fifteen years younger." He thought he would have everything ready by

September, but 1t dragged on till mid-October. But the result was charming not only in

his eyes but to everyone who saw it.

In reality it was just what is usually seen in the houses of people of moderate means 100

who want to appear rich, and therefore succeed only in resembling others like them•

selves: there were damasks, dark wood, plants, rugs, and dull and polished bronzes-all

the things people of a certain class have in order to resemble other people of that class.

His house was so like the others that it would never have been noticed, but to him it all

seemed to be quite exceptional. He was very happy when he met his family at the sta•

tion and brought them to the newly furnished house all lit up, where a footman in a

white tie opened the door into the hall decorated with plants, and when they went on

into the drawing-room and the study uttering exclamations of delight. He conducted

them everywhere, drank in their praises eagerly, and beamed with pleasure. At tea that

evening, when Praskovya Fedorovna among other things asked him about his fall, he

laughed and showed them how he had gone flying and had frightened the upholsterer.

Leo Tolsto~ 279

278 Chapter 8 • Henning l..c111g Srorirs 111111 '\o""'~

"It's a good thing I'm a bit of an athlete A

h

blut Idmer~lr knocl ked myself, just here; it hu;ts ;~;nei:,:::u~i:~tbhatv_e, been killed_

a rea y-1t son ya bruise."

' u Its Passing of

So they began living in their new home-in wh. h

they got thoroughly settled in they found the

. ic ' as always happens, when

the increased income, which as alwa s w . y w~re Just one room short-and wi

little, b~t it was all very nice.

Y as Just a lmle (some five hundred rubles) c!

Things went particularly well at first be£

h.

w~ile something had still to be done: th~ thi;e

I ~ was_finally arranged and

thmg moved, and something else adjusted. Tho~gh t~er: :e:: thmg o_rdered, another

husband and wife, they were both so well satisfied a d h d some dtSputes between

passed off without any serious quarrels Wh

h _n a so much to do that it all

rather dull and something seemed to ~ la k~n n~t in~ was left to arrange it became

tances, fonning habits, and life was growin: ~~f;r. ut t ey were then making acquainIvan Hych spent his mornings at the law courts d

first he was generally in a good humo th

an ~ame home to dinner, and at

on accou~t of his house. (Every spot ~n t~~~~b7:cr:~s1onally became irritable just

broken wmdow-blind string, irritated h ·m H h ~ or the upholstery, and every

arra~ging it all that every disturbance of tt distr;ss~ h ~e)o~ed so much trouble to

ran its course as he believed life should do: easily I im. I utdond the whole his life

He got up at nine drank his coff,

d h 'peasant y, an ecorously.

uniform and went to 'the law courts~e+:i::e :h: k r , an~ the~ put on his undress

already been stretched to fit h·

d h d

mess m which he worked had

·

•.

im an e onned it w"th

h· h

mqumes at the chancery, the chance i

. i_ out a itc : petitioners,

tive. In all this the thing was to exci dtself, anthe s~ttangs public and administradisturbs the regular course of official ~ e_ everyt ~ng esh ~nd vital, which always

with people, and then only on off• . lusmessds,an to admtt only official relations

.

ic1a groun

A ma

Id

wantmg some information Ivan Hych

. • h

n wou come, for instance

would have nothing to do. with h. . bas ~Fehm w ose sphere the matter did not lie:

his official capacity something t~:· u~~ bt e man had some business with him in

he would do everything, positive! ev:ou . e expressed ~n ?fficially stamped paper,

tions, and in doing so would maintai::t:n: he could w1th1_n the limits of such relathat is, would observe the courtesies of 1·£, A emblance of frie~dly human relations,

did everything else. Ivan Hych ssesse~e.h. s soon ~s the off1c1al relations ended, so

the official side of affairs and npoot . ht is ca~ac1ty to separate his real life from

.

mix t e two, m the h ·gh

d

d

practice and natural aptitude had brou h .

h

. I est egree, an by long

manner of a virtuoso, he would even a/ t ~~ to ~t a pitch that sometimes, in the

tions mingle. He let himself do th' . obew imseh to let the human and official rela1s Just cause e felt th h

Id

c hose resume the strictly official attitud

.

at e cou at any time he

did it all easily, pleasantly, correctl a~da!am and_dr_op ~he human relation. And he

the sessions he smoked drank tea y,h