Hawthorne's Females & Nature: Young Goodman Brown & Rappaccini's Daughter

advertisement

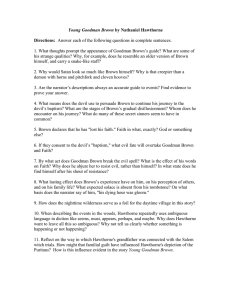

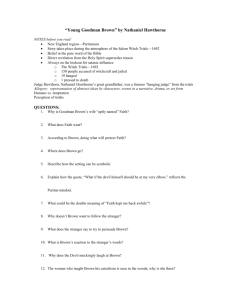

Females and Nature in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter” 51270400037 李维娜 2024.11.19 Nathaniel Hawthorne Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 -1864) is one of the greatest fiction writers of 19th-century American literature. Keywords: • Puritan ancestry (the Salem Witch Trials in the 1690s) • Moral metaphors with an anti-Puritan inspiration • Use of allegory and symbolism • Inherent evil and sin of humanity “His writings, to do them justice, are not altogether destitute of fancy and originality; they might have won him greater reputation but for an inveterate love of allegory, which is apt to invest his plots and characters with the aspect of scenery and people in the clouds, and to steal away the human warmth out of his conceptions.” --Nathaniel Hawthorne, prologue of “Rappaccini’s Daughter” 01 Young Goodman Brown Allegorical Representation of Faith Female Character Faith • An allegorical figure representing the Christian faith • The personification of virtue rather than a real woman Brown sees Faith as “[m]y love and my Faith,” “a blessed angel on earth” and plans to “cling to her skirts and follow her to Heaven (699).” He thinks that he will be saved through Faith, much as Puritans of the era expected to be saved through their faith in God, “For by grace are ye saved through faith”(Ephesians 2:8). Brown has deliberately conflated his wife’s name with a belief system (Keil 40). wife Faith ≈ faith itself Idealization of Faith The 19-century popular opinions about women’s superiority in morality and spirituality 女性解救者:The heroine as a benefactor to improve the hero’s moral development Allegorical Representation of Faith As Brown has been relying on Faith to save him, his belief in her differs from his belief in others both in degree and in kind. belief in Faith >> belief in others Brown’s reply to the revelations of the wickedness of his ancestors, Goody Cloyse, Deacon Gookin and the minister: “We are a people of prayer, and good works to boot, and abide no such wickedness” (701) . “What if a wretched old woman do choose to go to the devil when I thought she was going to heaven: is that any reason why I should quit my dear Faith and go after her?” (703) “With heaven above and Faith below, I will yet stand firm against the devil!” (704). Similar Pattern:Brown first expresses shock, then he dismisses the revelations and resolves to his belief in Faith. Allegorical Representation of Faith Brown’s Disillusion with Faith But something fluttered lightly down through the air and caught on the branch of a tree. The young man seized it, and beheld a pink ribbon. . “My Faith is gone!” cried he, after one stupefied moment. “There is no good on earth; and sin is but a name. Come devil; for to thee is this world given.” (705) Problems with the Idealization of Faith (1) Brown’s lofty attitude toward Faith is not an end in itself but is instrumental; Idealized Faith is supposed to provide him with an easy road to heaven (Magee 20). (2) Faith is not completely pure. Lust and sin affect both men and women. She cannot live up to the standards set by Brown. (3) Even if Faith is completely pure, her goodness could not save Brown. If he is to gain salvation at all, he must work it out himself “with fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12). Allegorical Representation of Faith Pink Ribbons According to an early Christian theologian Q. S. F. Tertullian, Christian women should only wear somber clothes to carry Eve’s guilt. Women are “the devil’s gateway” and have learned how to adorn themselves by consorting with fallen angels. Possible Interpretations • Faith is the “devil’s gateway” for her husband, leading him along the road to destruction rather than to heaven as Brown initially thinks. Faith can scarcely function as an allegorical virtue when her personal virtue is in doubt. • Pink is neither white nor red, but a color in between, indicating a psychological state that is neither wholly corrupted nor entirely innocent, but rather somewhere in the middle. Pink ribbons symbolize the tainted innocence and spiritual imperfection of human beings (Wagenknecht 62). Social Implications in 1692 (the time within the narrative) Puritanism The Duality of Human Nature • Dichotomy between goodness and evil (非善即恶的二分法) If “evil is human nature” is true, then there is no place for goodness. • The struggle between good and evil within human nature • The dark, troubled Puritan mind could not tell the innocent from the demonic, the sinner from the saint. • Whether Faith obeyed, he knew not (708). • Even the most pious individuals may harbor sinful desires. • The good shrank not from the wicked, nor were the sinners abashed by the saints (706). Brown cannot decide which is real: the sanctity he sees in the village by day? the depravity he sees in the forest at night? Brown’s gloomy lifetime after that night in the forest: A critique of the Puritans’ suspicious, spectral, and judgmental outlook Social Implications in 1835 (the time Hawthorne published the story) 炉边天使:Changing gender roles in the nineteenth-century America Brown’s “blessed angel” Women as “Angel in the House” With the Industrial Revolution pulling men out of the home, the new construction of gender assigned men the task of providing, women that of nurturing. At the beginning, Brown kissed goodbye Faith, with him outside and Faith inside the house. Despite her pleading, Brown refuses to stay home with Faith. Brown only sees her goodness and is unable to see her fears, needs, and sins. At the end, Brown apparently considers her in terms of sin. Both of his perspectives (angelic Faith / demonic Faith), deny the couple the possibility of an authentic adult relationship (Magee 21). The story certainly critiques the puritan mind on trial, but it also critiques the sweet view of women in Hawthorne’s era. 02 Rappaccini's Daughter Female Individuality & the Dominant Male Perspective Beatrice “Constructed” as a Poisonous Woman • Transformed into a poison by her father Rappaccini Beatrice is a science experiment from birth She lives only to fulfill the requirements of a dutiful daughter • Regarded as an academic rival by Doctor Pietro Baglioni Her destruction is simply the means by which Baglioni punishes Rappaccini for his unholy science. • Reimagined as either an idealized lover or a poisonous woman by her lover Giovanni Side of life: beauty, angelic spirit Side of death: Beatrice’s poisonous nature, her ability to cause death The unacceptance of both sides of woman (Hallenbeck 14) Female Individuality & the Dominant Male Perspective Conflation of Sexual Maturity, Toxicity, and Virtue Sexually imposing Toxic Non-toxic → → → Toxic, fearful Cannot be virtuous, monstrous in soul Harmless, innocent Giovanni cannot understand that Beatrice can be at once desirable—that is, poisonous, and virtuous. If Beatrice is a poisonous woman, then she cannot be good. Giovanni believes that those “dreadful peculiarities” in her physical being cannot exist without some “corresponding monstrosity of soul” (782). He remains that “the physical directly implies the moral”(Bensick 48). Therefore, Beatrice’s body must match her soul—she must be given the antidote. Female Individuality & the Dominant Male Perspective Man’s Lack of Understanding and Need to Control As Hallenbeck states, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” can be interpreted as a story where woman is victim to man’s lack of understanding and his need to control. The patriarchal culture has given Giovanni the need to control his environment. He cannot accept anything that he does not understand, and tries to perfect or change those things . Baglioni also facilitates the destruction of Beatrice. Only after Baglioni captivates Giovanni with a sinister story, Beatrice is redefined from a beauty into a monster who must be cured of her physical abnormality. Physical Reality: • A malevolent force? • Being deadly to men? Denied Unproven Female Individuality & the Dominant Male Perspective Beatrice’s Voice and Triumph “Giovanni, believe it, thought my body be nourished with poison, my spirit is God’s creature, and craves love as its daily food […] But it was not I. Not for a world of bliss would I have done it.” (785) “Farewell, Giovanni! Thy words of hatred are like lead within my heart; but they too will fall away as I ascend. Oh, was there not, from the first, more poison in thy nature than in mine?” (786) While Beatrice may be unfairly reduced to her poisonousness, she takes solace in knowing that her nature is benevolent. When we readers strip away the story of the “poisonous woman,” we find, in the end, just a woman (Crouse 36). Female Individuality & the Dominant Male Perspective Symbolism and “Marked Woman” • Beatrice in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” (1844) --reduced to the relation to a male figure, her father • Georgiana in “The Birth-Mark”(1843) --reduced to a birthmark • Hester in The Scarlet Letter (1850) --reduced to the scarlet letter she wears on her chest As these titles imply, women protagonists of these stories do not have control over their interpretation. Also, they all had tragedy inflicted upon them by outside forces. • Hooper in “The Minister's Black Veil” --chooses to wear the black veil • Arthur Dimmesdale in The Scarlet Letter --has control over his body Among them, Hester becomes empowered by her symbol and her ability to influence its meaning, whose definition begins with the self. 03 Nature in the Two Stories Nature in the Two Stories • Nature as a boundary For Giovanni, garden represents an unknown world. The secret entrance into the garden is the boundary between the realm of safety and familiarity and a place with unknown realities, rules, and possibilities (Hallenbeck 33). For Goodman Brown, the journey into the forest can be seen as a descent from consciousness to the subconscious, from reality to illusion, and from light to darkness (Cook 478). • Nature as symbols and psychological truth The forest is a symbol of the subconscious mind where Brown confronts his inner demons and the darker aspects of human nature. Brown's night in the forest is a metaphorical representation of a psychological ordeal that anyone might face. Nature in the Two Stories Is Brown’s journey into the forest merely a dream? Had Goodman Brown fallen asleep in the forest and only dreamed a wild dream of a witch-meeting? Be it so if you will; but, alas! It was a dream of evil omen for young Goodman Brown (709) . “You must look through the surface of American art and see the inner diabolism of the symbolic meaning, otherwise it is all mere childishness.” --D. H. Lawrence This dream is symbolically true. The symbolic forest of the night is, in effect, young Goodman Brown's own dark soul, where belief turns into doubt, faith into skepticism, and where the people encountered are the implications of his daily familiars and ancestral past. Works Cited Bensick, Carol Marie. La Nouvelle Beanice: Renaissance and Romance in “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1985. Cook, Reginald. “The Forest of Goodman Brown’s Night: A Reading of Hawthorne’s ‘Young Goodman Brown’.” New England Quarterly, vol.43, no.3, 1970, pp. 473-481. Crouse, Kathleen Mary, Poison in the System: Symbols on the Body and the Body as a Symbol in Select Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Legacy Theses & Dissertations (2009-2024), 2011. Hadella, Charlotte C. Women in Gardens in American Short Fiction, University of New Mexico, 1989. ProQuest. Hallenbeck, Kathy H. Completing the Circle: A Study of the Archetypal Male and Female in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter”, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2002. Jin, Hengshan. “The Cold War Mentality—Reading The Crucible from the Textual and Social-cultural Perspectives.” English and American Literary Studies, vol. 1, 2016, pp.177-190. [ 金 衡 山 . 直 面 冷 战 逻 辑 —— 《 萨 勒 姆 女 巫 》 中 的 背 景 和 现 实 再 现 . 英 美 文 学 研 究 论 丛 ,2016,(01):177190.DOI:10.16754/b.cnki.ymwxyjlc.2016.01.014. ] Keil, James C. “Hawthorne’s ‘Young Goodman Brown’: Early Nineteenth-Century and Puritan Constructions of Gender.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 69, no.1, 1996, pp. 33-55. Works Cited Magee, Bruce R. “Faith and Fantasy in ‘Young Goodman Brown.’” Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 1-24. JSTOR. Moran, Kathleen. “Hawthorne & the Duality of Human Nature in ‘Young Goodman Brown’ & ‘My Kinsman, Major Molineux’.” IUSB Graduate Research Journal, vol. 2, 2015, pp. 21-36. Petagna, Isabelle. Why they Stay: An Ecofeminist Reading of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Rappaccini’s Daughter” and “The Birthmark”, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2022. Talebpour Sheshvan, Narmin, and Farah Ghaderi. "An Eco-Gothic Reading of Hawthorne’s ‘Young Goodman Brown’ and ‘Roger Malvin’s Burial’.” Textual Practice, vol. 35, no. 12, 2021, pp. 1925-1939. Tertullian, Quintus S. F. Tertulliani Opera. Ed.Eligius Dekkers. Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina. 1-2. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1954. Wagenknecht, Edward. Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Man, His Tales and Romances. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1989. Wohlpart, Jim. “The Second Great Awakening in Hawthorne’s ‘Young Goodman Brown.’” Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, vol. 26, no. 1, 2000, pp. 33-46. JSTOR. Thank you! 感谢倾听 敬请批评指正