I

Preliminaries

1.1

P ROBABILITY

1.1.1

BASICS

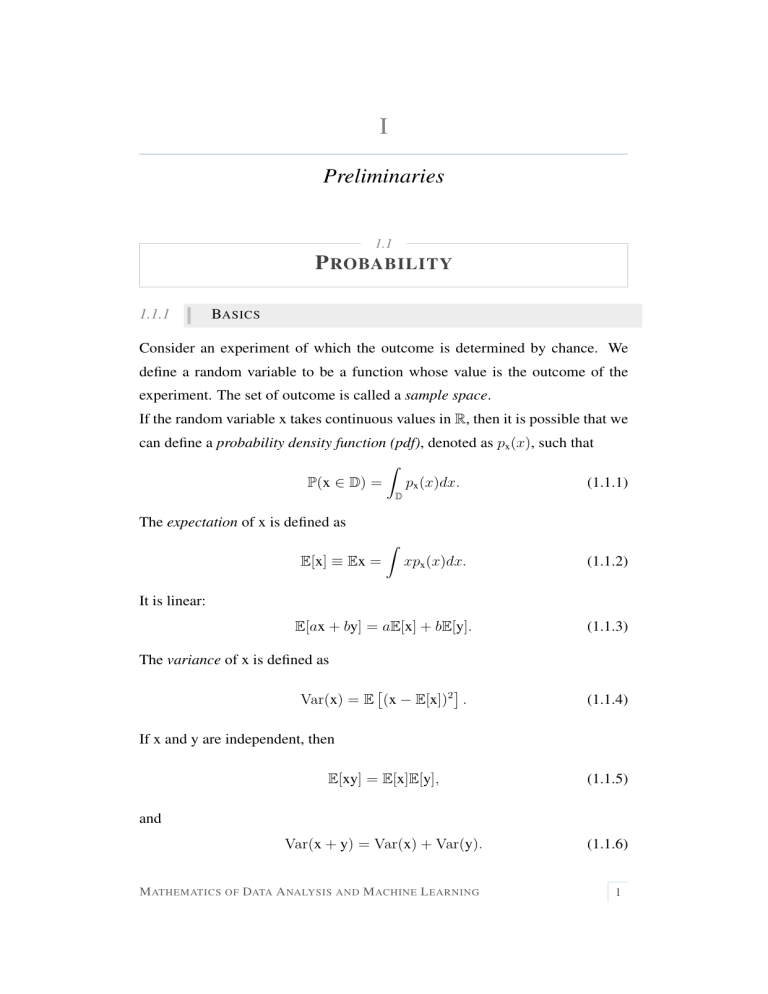

Consider an experiment of which the outcome is determined by chance. We

define a random variable to be a function whose value is the outcome of the

experiment. The set of outcome is called a sample space.

If the random variable x takes continuous values in R, then it is possible that we

can define a probability density function (pdf), denoted as px (x), such that

Z

P(x ∈ D) =

px (x)dx.

(1.1.1)

D

The expectation of x is defined as

Z

E[x] ≡ Ex =

xpx (x)dx.

(1.1.2)

E[ax + by] = aE[x] + bE[y].

(1.1.3)

It is linear:

The variance of x is defined as

Var(x) = E (x − E[x])2 .

(1.1.4)

If x and y are independent, then

E[xy] = E[x]E[y],

(1.1.5)

Var(x + y) = Var(x) + Var(y).

(1.1.6)

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

1

and

Preliminaries

I

1.1.2

G AUSSIAN

If a random variable x that takes value in R follows the Gaussian distribution,

it has the Gaussian density, given by

px (x) ≡ N (x|µ, σ 2 ) := √

(x−µ)2

1

e− 2σ2 .

2πσ

(1.1.7)

When µ = 0 and σ 2 = 1, it has the standard normal distribution:

x2

1

N (x|0, 1) = √ e− 2 .

2π

Proposition 1.1.1. For t > 0,

Z ∞

2

2

e−x dx ≤

t

Proof. First note

Z ∞

−x2

e

(1.1.8)

Z ∞

dx ≤

t

t

e−t

.

2t

(1.1.9)

x −x2

e dx.

t

(1.1.10)

2

2

Apply change of variable u = e−x with du = −2xe−x dx. Then,

Z ∞

Z 0

2

e−t

1

x −x2

e dx =

.

− du =

t

2t

2t

t

e−t2

(1.1.11)

■

In high dimension, a random vector x ∈ RD follows the Gaussian distribution

if its pdf is

1

⊤ −1

px (x) ≡ N (x|µ, Σ) :=

− (x − µ) Σ (x − µ) .

1 exp

D

2

(2π) 2 |Σ| 2

(1.1.12)

1

From now on, we do not distinguish x with x, or x with x, unless it is really

necessary.

A Gaussian depends on x through

∆2 = (x − µ)⊤ Σ−1 (x − µ),

(1.1.13)

where ∆ is called the Mahalanobis distance from µ to x. When Σ = I, then

the Mahalanobis distance reduces to the regular ℓ2 norm in RD .

2

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Gaussian

1.1.2

Proposition 1.1.2. N (x|µ, Σ) is indeed a pdf.

Proof. First, decompose Σ =

PD

⊤

i=1 λi µi µi .

Then, Σ−1 =

PD

−1

⊤

i=1 λi µi µi .

Then,

D

X

∆2 = (x − µ)⊤

!

⊤

λ−1

i µi µi

(x − µ)

(1.1.14)

i=1

=

D

X

⊤

⊤

λ−1

i (x − µ) µi µi (x − µ)

|

{z

}

{z }

|

i=1

=:yi

=

D

X

(1.1.15)

=yi

2

λ−1

i yi .

(1.1.16)

i=1

This implies that the contours of Gaussians are ellipsoids. Let y = [y1 · · · yD ]⊤ .

Then,

− u⊤

−

1

..

y = U(x − µ) =

(x − µ).

.

⊤

− uD −

(1.1.17)

Consider the change of variable x 7→ y. The Jacobian J satisfies

∂yj

= Uji .

∂xi

(1.1.18)

= U⊤ U = |I| = 1.

(1.1.19)

Jij =

That is, J = U⊤ . We have

|J|2 = U⊤

2

Therefore,

Z

Z

p(x)dx =

RD

p(y)dy.

(1.1.20)

RD

On the other hand,

1

1

D

1 X −1 2

exp

−

λ y

p(y) =

1

D QD

2 i=1 i i

(2π) 2 ( i=1 λi ) 2

D

Y

1

1

1 yi2

√ √ exp −

=

.

2

λ

λ

2π

i

i

i=1

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

!

(1.1.21)

(1.1.22)

3

Preliminaries

I

Hence,

Z

Z Y

D

1

1

1 yi2

√ √ exp −

p(y)dy =

dy1 · · · dyD

2

λ

λ

2π

i

i

i=1

D

YZ 1

1

1 yi2

√ √ exp −

=

dyi

2 λi

2π λi

i=1

=

D

Y

1 = 1.

(1.1.23)

(1.1.24)

(1.1.25)

i=1

Hence,

R

p(x)dx =

R

p(y)dy = 1.

■

Proposition 1.1.3. Ex∼N (µ,Σ) [x] = µ.

Proof.

Z

E[x] =

xp(x)dx

(1.1.26)

Z

1

exp − (x − µ)⊤ Σ−1 (x − µ) xdx

2 | {z }

(2π) |Σ|

=:z

Z

1 ⊤ −1

1

exp − z Σ z (z + µ)dz

=

1

D

2

(2π) 2 |Σ| 2

|

{z

}

=

1

D

2

1

2

(1.1.27)

(1.1.28)

even function

= µ.

(1.1.29)

■

Proposition 1.1.4. Covx∼N (µ,Σ) (x) = Σ.

Proof. Note that Cov(x) = E[xx⊤ ]−E[x]E[x]⊤ = E[xx⊤ ]−µµ⊤ . We consider

Z

1

1

exp − (x − µ)⊤ Σ−1 (x − µ) xx⊤ dx (1.1.30)

E[xx⊤ ] =

1

D

2 | {z }

(2π) 2 |Σ| 2

=:z

Z

1

1 ⊤ −1

=

exp − z Σ z (z + µ)(z + µ)⊤ dz (1.1.31)

1

D

2

2

(2π) 2 |Σ|

Z

1

1 ⊤ −1

⊤

⊤

=

exp − z Σ z (zz⊤ + zµ

+

µz

+ µµ⊤ )dz

1

D

2

2

(2π) 2 |Σ|

(1.1.32)

4

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Inequalities

1.1.3

Z

1

⊤

= µµ +

1

D

(2π) 2 |Σ| 2

1 ⊤ −1

exp − z Σ z zz⊤ dz.

2

(1.1.33)

Apply change of variable y = U(x − µ) = Uz. Then z = U⊤ y and

⊤

⊤

⊤

zz = U yy U =

D X

D

X

ui yi yj u⊤

j =

i=1 j=1

D X

D

X

yi yj ui u⊤

j .

(1.1.34)

i=1 j=1

Therefore,

E[xx⊤ ] = µµ⊤ +

Z

1

D

2

(2π) |Σ|

1

2

D

1 X yk2

exp −

2 k=1 λk

! D D

XX

yi yj ui u⊤

j dy

i=1 j=1

| {z }

odd if i ̸= j

(1.1.35)

Z

1

⊤

= µµ +

D

2

1

2

exp −

(2π) |Σ|

D Z

X

1

! D

D

1 X y2 X

k

2 k=1 λk

yi2 ui u⊤

i dy (1.1.36)

i=1

!

2

y

1

k

yi2 ui u⊤

−

= µµ⊤ +

1 exp

i dy (1.1.37)

D

2

λ

2

k

2 |Σ|

(2π)

i=1

k=1

Z

D

2

X

1

1 yi

= µµ⊤ +

exp

−

yi2 ui u⊤

(1.1.38)

1

i dyi

1

2

λ

2

i

2

(2π) λi

i=1

D

X

= µµ⊤ +

λi ui u⊤

(1.1.39)

i

D

X

i=1

⊤

= µµ + Σ.

(1.1.40)

Hence,

Cov(x) = E[xx⊤ ] − µµ⊤ = Σ.

(1.1.41)

■

1.1.3

I NEQUALITIES

Theorem 1.1.5 (Markov inequality). Let x ≥ 0 be a non-negative random variable. Then for a > 0,

P(x ≥ a) ≤

E[x]

.

a

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

(1.1.42)

5

Preliminaries

I

Proof.

Z ∞

xp(x)dx

E[x] =

Z0 a

(1.1.43)

Z ∞

=

xp(x)dx +

xp(x)dx

a

Z ∞

ap(x)dx

≥0+

(1.1.44)

0

(1.1.45)

a

= aP(x ≥ a).

(1.1.46)

■

Theorem 1.1.6 (Chebyshev inequality). Let x be a random variable with E[x] <

∞ and Var(x) < ∞. Then for a > 0,

P(|x − E[x]| ≥ a) ≤

Var(x)

.

a2

(1.1.47)

Proof.

P(|x − E[x]| ≥ a)

(1.1.48)

= P(|x − E[x]|2 ≥ a2 )

E |x − E[x]|2

≤

a2

Var(x)

.

=

a2

(1.1.49)

(1.1.50)

(1.1.51)

■

Corollary 1.1.7 (Weak law of large numbers). Let x1 , · · · , xn be i.i.d. random

variables, where E[xi ] = µ and Var(xi ) = σ 2 for all i. Then,

x1 + · · · + xn

σ2

P

− µ ≥ ϵ ≤ 2.

n

nϵ

Proof. By the Chebyshev inequality,

n

Var x1 +···+x

x1 + · · · + xn

n

P

−µ ≥ϵ ≤

n

ϵ2

1

= 2 2 Var(x1 + · · · + xn )

nϵ

6

(1.1.52)

(1.1.53)

(1.1.54)

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Inequalities

1.1.3

n

1 X

σ2

= 2 2

Var(xi ) = 2 .

n ϵ i=1

nϵ

(1.1.55)

■

Remark 1.1.8 (Central limit theorem). Under the same assumptions as in the

weak law of large numbers,

1

n→∞

√ (x1 + · · · + xn − nµ) −→ N (0, σ 2 ).

n

(1.1.56)

Note that this is a result that requires n → ∞. The following inequalities can

establish bounds for finite n’s.

Theorem 1.1.9 (Chernoff bounds). Let x1 , · · · , xn be i.i.d. Bernoulli random

variables such that

(

1 with probability p

xi =

0 with probability 1 − p

Define S :=

Pn

i=1 xi . Also, define m := E[S] =

(1.1.57)

Pn

i=1 E[xi ] = np. Then,

1. for δ > 0,

P(S ≥ (1 + δ)m) ≤

eδ

(1 + δ)1+δ

m

1 2

1 3

≤ e− 2 δ m+ 6 δ m ;

(1.1.58)

2. for 0 < γ < 1,

e−γ

(1 − γ)1−γ

m

γ2m

≤ e− 2 .

(1.1.59)

E[eλS ]

P(S ≥ (1 + δ)m) = P eλS ≥ e(1+δ)λm ≤ (1+δ)λm

e

(1.1.60)

P(S ≤ (1 − γ)m) ≤

Proof. 1. For any λ > 0,

by the Markov inequality. Since x1 , · · · , xn are independent,

" n

#

Y

Pn

E[eλS ] = E[eλ i=1 xi ] = E

eλxi

(1.1.61)

i=1

=

n

Y

i=1

E[eλxi ] =

n

Y

eλ p + 1(1 − p)

(1.1.62)

i=1

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

7

Preliminaries

I

=

n

Y

p(eλ − 1) + 1 .

(1.1.63)

i=1

Using the fact that 1 + x ≤ ex for all x ∈ R, we have

E[eλS ] ≤

n

Y

λ

ep(e −1) .

(1.1.64)

i=1

Thus we have

Qn

p(eλ −1)

i=1 e

.

eλ(1+δ)m

P(S ≥ (1 + δ)m) ≤

(1.1.65)

Taking λ = log(1 + δ) yields

Qn

P(S ≥ (1 + δ)m) ≤

pδ

epδn

i=1 e

=

(1 + δ)(1+δ)m

(1 + δ)(1+δ)m

eδm

=

=

(1 + δ)(1+δ)m

eδ

(1 + δ)(1+δ)

(1.1.66)

m

.

(1.1.67)

By Taylor expansion about 0,

1

1

1

(1 + δ) log(1 + δ) = δ + δ 2 − δ 3 + ζ 4 ,

2

6

12

(1.1.68)

for some ζ between 0 and δ. Therefore,

eδ

exp(δ)

=

1 4

1 2

(1+δ)

(1 + δ)

ζ

exp δ + 2 δ − 16 δ 3 + 12

exp(δ)

≤

exp δ + 21 δ 2 − 16 δ 3

1 2 1 3

= exp − δ + δ .

2

6

This implies that

eδ

(1 + δ)1+δ

m

1 2

1 3

≤ e− 2 δ m+ 6 δ m .

(1.1.69)

(1.1.70)

(1.1.71)

(1.1.72)

2. For any λ > 0,

E[e−λS ]

P(S ≤ (1 − γ)m) = P eλ−S ≥ e−(1−γ)λm ≤ −(1−γ)λm

e

(1.1.73)

by the Markov inequality. Similarly as before, since x1 , · · · , xn are independent,

" n

#

Y

Pn

e−λxi

(1.1.74)

E[e−λS ] = E[e−λ i=1 xi ] = E

i=1

8

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Inequalities

1.1.3

=

=

n

Y

i=1

n

Y

−λxi

E[e

]=

n

Y

e−λ p + 1(1 − p)

(1.1.75)

i=1

n

Y

−λ

p(e−λ − 1) + 1 ≤

ep(e −1) .

i=1

(1.1.76)

i=1

Thus we have

p(e−λ −1)

i=1 e

.

e−λ(1−γ)m

Qn

P(S ≤ (1 − γ)m) ≤

Taking λ = − log(1 − γ) = log(1/(1 − γ)) yields

m

e−γ

P(S ≤ (1 − γ)m) ≤

.

(1 − γ)(1−γ)

(1.1.77)

(1.1.78)

Again, using the Taylor expansion

1

1

1

(1 − γ) log(1 − γ) = −γ + γ 2 + γ 3 + ζ 4 ,

2

6

12

(1.1.79)

1 2 1 3

1 4

= exp −γ + γ + γ + ζ .

2

6

12

(1.1.80)

we have

1−γ

(1 − γ)

Therefore,

1

e−γ

= 1 2 1 3

1 4

(1−γ)

(1 − γ)

γ + 6 γ + 12

ζ

2

1

1 2

≤ 1 2 = exp − γ .

2

γ

2

(1.1.81)

(1.1.82)

(1.1.83)

Therefore,

e−γ

(1 − γ)(1−γ)

m

1 2

≤ exp − γ m .

2

(1.1.84)

■

Theorem 1.1.10 (Hoeffding inequality). Let x1 , · · · , xn be independent variables with xi ∈ [0, 1] for all i. Then for any t ≥ 0,

!

n

n

1X

1X

P

xi −

E[xi ] ≥ t ≤ exp −2nt2 .

n i=1

n i=1

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

(1.1.85)

9

Preliminaries

I

We first establish a lemma in order to prove the Hoeffding inequality.

Lemma 1.1.11. If a random variable x takes values in [0, 1], then for any s ≥ 0,

s2

E es(x−E[x]) ≤ e 8 .

(1.1.86)

Proof of lemma. Let f be the logarithm of the left-hand-side quantity:

Then

f (s) := log E es(x−E[x]) .

(1.1.87)

E (x − E[x])es(x−E[x])

,

f (s) =

E [es(x−E[x]) ]

(1.1.88)

′

and

i

s(x−E[x]) 2

2 s(x−E[x])

E (x − E[x])e

E (x − E[x]) e

f ′′ (s) =

−

2

E [es(x−E[x]) ]

(E [es(x−E[x]) ])

(1.1.89)

From this form, we see that f ′′ (s) is the variance of a random variable x̃ ∈ [0, 1].

Hence, we have

′′

2

f (s) = Var(x̃) = min E (x̃ − m)

m∈[0,1]

1

1 2

1

≤ E (x̃ − ) =

(2x̃ − 1)2 ≤ .

2

4

4

(1.1.90)

By Taylor’s theorem, for some θ between 0 and s, we have

s2 ′′

s2 ′′

s2 1

s2

f (s) = f (0) + sf (0) + f (θ) = 0 + 0 + f (θ) ≤

· = . (1.1.91)

2

2

2 4

8

′

Hence,

s2

E es(x−E[x]) = exp(f (s)) ≤ e 8 .

(1.1.92)

■

Now we are ready to prove the main result.

Proof of the Hoeffding inequality.

P

10

!

n

n

1X

1X

xi −

E[xi ] ≥ t

n i=1

n i=1

(1.1.93)

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Maximum likelihood

1.2

1 Pn

1 Pn

= P es( n i=1 xi − n i=1 E[xi ]) ≥ est

h 1 Pn

i

1 Pn

s( n i=1 xi − n

E[xi ])

i=1

E e

≤

st

s (xe−E[x ]) Qn

i

E en i

(by independence)

= i=1

est

Qn

s2

8n2

i=1 e

(by lemma)

≤

est

s2

= exp

− st .

8n

(1.1.94)

(1.1.95)

(1.1.96)

(1.1.97)

(1.1.98)

Since this holds for any s ≥ 0, we take s = 4nt and the Hoeffding inequality

■

follows.

We conclude this section by stating the Bernstein inequality without proving it.

Theorem 1.1.12 (Bernstein inequality). Let x1 , · · · , xn be n independent random variables such that |xi | ≤ c and E[xi ] = 0 for all i. Then, for t ≥ 0,

!

n

nt2

1 X

P

xi ≥ t ≤ 2 exp − 2

,

(1.1.99)

n i=1

2σ + 2ct/3

where σ 2 = n1

Pn

i=1 Var(xi ).

1.2

M AXIMUM LIKELIHOOD

It is crucial, in many applications, to estimate the density or probability of distributions. Parametric methods offer one approach to achieve this by assuming

a specific functional form for the distribution and then estimating its parameters

from the data. This allows us to create a model that represents the data distribution, enabling us to make decisions based on this representation. The choice

of the distribution’s functional form often depends on the nature of the data and

the assumptions we are willing to make about its underlying structure.

Suppose p(x|θ) is a model for generating data, where θ denotes (a vector repi.i.d.

resentation of) the parameters within the model. Let x1 , · · · , xn ∼ p(x|θ) be

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

11

Preliminaries

I

available data points. The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for θ is then

θ̂MLE = arg max p(x1 , · · · , xn |θ)

(1.2.1)

θ

= arg max

θ

n

Y

p(xi |θ)

(1.2.2)

log p(xi |θ) log-likelihood.

(1.2.3)

i=1

= arg max

θ

n

X

i=1

Example 1.2.1 (Gaussian density (one-dimensional)). Let’s look at an example of calculating the MLE. Recall that the parameters in the Gaussian density

N (µ, σ 2 ) are µ and σ.

i.i.d.

Given a dataset X = {xi }ni=1 ∼ N (µ, σ 2 ), the likelihood is

n

n

Y

Y

1

(xi − µ)2

2

√

p(X |µ, σ) =

N (xi |µ, σ ) =

exp −

.

2σ 2

2πσ

i=1

i=1

(1.2.4)

The log-likelihood is

n

X

n

(xi − µ)2

log p(X |µ, σ) = − log(2π) − n log(σ) −

.

2

2σ 2

i=1

(1.2.5)

We need to solve the following optimization problem:

n

X

n

(xi − µ)2

max − log(2π) − n log(σ) −

.

2

µ,σ

2

2σ

i=1

|

{z

}

(1.2.6)

=:f (µ,σ)

Set

n

X

∂f

xi − µ set

=

= 0;

2

∂µ

σ

i=1

Pn

(xi − µ)2 set

n

∂f

= − + i=1 3

= 0.

∂σ

σ

σ

From (1.2.7),

(1.2.7)

(1.2.8)

Pn

µ=

i=1 xi

n

= m (sample mean).

(1.2.9)

From (1.2.8),

Pn

Pn

2

(xi − m)2

n−1 2

2

i=1 (xi − µ)

= i=1

=

s (sample variance).

σ =

n

n

n

(1.2.10)

12

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405

Singular value decomposition

1.3

We conclude that

µ̂MLE = m;

2

σ̂MLE

=

n−1 2

s.

n

(1.2.11)

1.3

S INGULAR VALUE DECOMPOSITION

Theorem 1.3.1 (SVD). Let A be an m × n real matrix with m ≥ n. Then

A = UΣV⊤

where U is an m × n matrix with U⊤ U = In ; V is an n × n matrix with

V⊤ V = In ; and Σ = diag(σ1 , · · · , σn ) with σ1 ≥ · · · ≥ σn ≥ 0. The columns

u1 , · · · , un of U are called left singular vectors; the columns v1 , · · · , vn of V

are called right singular vectors. σ1 , · · · , σn are called singular values.

Proof. For A = 0 we can take Σ to be the zero square matrix and U and V to

be arbitrary matrices such that U⊤ U = In and V⊤ V = In .

For A ̸= 0, we argue by induction. For n = 1, A is a vector, and we can write

A = UΣV⊤ where U = A/ ∥A∥2 , Σ = ∥A∥2 and V = 1.

Now suppose the conclusion holds for (m − 1) × (n − 1) matrices, we want to

show it for m × n (the induction step). Choose v ∈ Rn such that ∥v∥2 = 1 and

∥Av∥2 = ∥A∥2 > 0. Let

u=

Av

.

∥Av∥2

Choose Ũ and Ṽ so that U = [u, Ũ] is m × m unitary matrix, and V = [v, Ṽ]

is an n × n unitary matrix.

Now write

⊤

U AV =

u⊤

Ũ⊤

Then

u⊤ Av =

A v Ṽ

=

u⊤ Av u⊤ AṼ

Ũ⊤ Av Ũ⊤ AṼ

(Av)⊤ (Av)

= ∥Av∥2 = ∥A∥2 = σ1 .

∥Av∥2

Also,

Ũ⊤ Av = Ũ⊤ u ∥Av∥2 = 0 .

M ATHEMATICS OF DATA A NALYSIS AND M ACHINE L EARNING

13

Preliminaries

I

We claim that u⊤ AṼ = 0 since otherwise,

σ1 = ∥A∥2 = U⊤ AV 2 ≥ [1, 0, · · · , 0]U⊤ AV 2 = [σ1 |u⊤ AṼ]

2

> σ1 ,

which is a contradiction. 1

Now

⊤

σ1

0

0 ŨAṼ⊤

U AV =

=

σ1 0

0 Ã

Note that à = ŨAṼ⊤ is an (m − 1) × (n − 1) matrix. So à = U1 Σ1 V1⊤ (what

are the sizes of the matrices?). Therefore,

⊤

U AV =

σ1

0

0 U1 Σ1 V1⊤

σ1 0

0 Σ1

σ1 0

0 Σ1

⊤

1 0

.

V

0 V1

=

1 0

0 U1

σ1 0

0 Σ1

That is,

A=U

1 0

0 U1

1 0

0 V1

⊤

1 0

0 V1

⊤

.

V⊤ ,

or equivalently,

A=

U

1 0

0 U1

■

Remark 1.3.2. SVD tells us that any matrix, as a linear transform, maps a vector

P

P

x = nj=1 βj vj to y = Ax = nj=1 σj βj uj . That is, any matrix is diagonal as

long as we can choose the appropriate orthogonal coordinate system.

1

Equivalently, otherwise we can find a column vector in Ṽ, which we call ṽ, such that

u Aṽ ̸= 0. This would mean v ⊤ A⊤ Aṽ ̸= 0. Then there exists a vector v♯ in the span of v

and ṽ such that ∥Av♯ ∥2 / ∥v♯ ∥ > σ1 . Contradiction.

⊤

14

L ECTURE N OTES FOR MATH 405