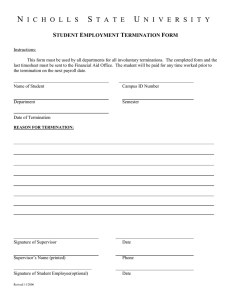

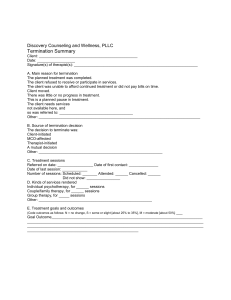

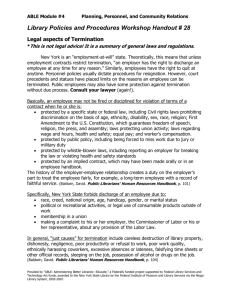

Performance Improvement As in any relationship, there are times when disagreements occur; in the employment rela- tionship, these disagreements are usually related to some form of performance issue and can result in a disciplinary action. Much has been written about this topic, because it can become a source of legal action if the employer doesn’t act appropriately. HR’s role in the disciplinary process is to provide the expertise needed to set up a fair and equitable process that is applied consistently throughout the organization. Organizations with effective ER programs work to prevent the need for disciplinary action. The establishment and publication of clear policies, procedures, and work rules combined with clearly communicated expectations for individual employees are the cor- nerstones of prevention. With regular feedback, both positive and negative, employees are better able to improve performance issues when they’re easily remedied. If a performance problem can’t be resolved at this level, the supervisor moves into a formal progressive disci- plinary process. Discipline is a performance management tool that is designed to modify employee behav- ior through the use of negative consequences. Many companies have a formal code of con- duct that is used to communicate examples of expected employee behavior, and when an employee fails to behave in accordance with policy, discipline may be used. HR is responsible for creating the discipline policy, communicating the code of conduct, and ensuring that the administration of the policy doesn’t violate the law. A good discipline policy doesn’t neces- sarily have to tie an employer to specific steps in the discipline process, but rather makes a statement about the employee’s responsibilities and the consequences for failing to execute those responsibilities in accordance with company guidelines. With wrongful-termination and wrongful-discipline lawsuits on the rise, it’s imperative that HR is up to date on the stan- dards pertaining to employee discipline. A seemingly neutral code of conduct that negatively impacts a protected-class group may be found to be discriminatory. Furthermore, disciplin- ing or terminating an employee for exercising their leave rights, for reporting harassment, or to avoid paying a sales commission are all examples of wrongful discipline/discharge. Disciplinary Terminations In progressive disciplinary situations, if informal coaching and the initial stages of the disciplinary process don’t remedy the performance problem, it’s time to move to the termi- nation stage. When this becomes necessary, the manager should work with HR to ensure that, to the extent possible, all necessary steps have been taken to prevent legal action as a result of the termination. As discussed earlier in this chapter, due process isn’t required in employment actions taken by private employers, but ensuring that employees are informed of the issues and given the opportunity to tell their side of the story demonstrates that the employer treats them in a fair and equitable manner. In cases where employee actions create a dangerous situation for the employer, as in theft of company property or violence in the workplace, the employer should move imme- diately to the termination phase of the disciplinary process. When this occurs, the best course of action is to suspend the employee pending an investigation, conduct the investigation in a fair and expeditious manner, and, should the results of the investigation support termination, terminate the employee. Terminations are always difficult situations, and HR professionals need to be able to provide support for managers who must take this action. There are two areas in which HR’s expertise is critical: counseling supervisors before the termination meeting and providing information so that managers avoid wrongful-termina- tion claims. The Termination Meeting Termination meetings are among the most difficult duties any supervisor has to perform. When termination becomes necessary, HR should meet with the supervisor to ensure that there is sufficient documentation to support the action and to coach the supervisor on how to appropriately conduct the meeting. By this stage in the process, the employee should not be surprised by the termination, because it should have been referred to as a consequence if improvement didn’t occur. The meeting should be long enough to clearly articulate the rea- sons for the termination and provide any final papers or documentation. Managers should be counseled to be professional, avoid debating the action with the employee, and conclude the meeting as quickly as possible. The timing of termination meetings is a subject of disagreement as to the “best” day and time. Taking steps to ensure that the termination occurs with as little embarrassment for the employee as possible should be the guiding factor in making this decision. Once the meeting is completed, and, of course, depending on corporate policy and the circumstances surrounding the termination, the employee may be escorted from the build- ing. Company policies differ on this part of the process: some companies have a security officer escort the employee from the building; others allow the employee to pack up personal items from the desk with a supervisor or security officer present. While the supervisor is conducting the termination meeting, facilities and IT personnel are often simultaneously taking steps to prevent the employee from accessing the company network or facilities once the termination has been completed. In any situation with the possibility of the employee becoming violent, HR should arrange for security personnel to be nearby or, in extreme cases, ensure that the local police department is advised of the situation. Wrongful Termination Wrongful terminations occur when an employer terminates someone for a reason that is prohibited by statute or breaches a contract. For example, an employee may not be terminated because they’re a member of a protected class. If an employer gives a different reason for the termination but the employee can prove that the real reason was based on a discriminatory act, the termination would be wrongful. Similarly, an employee may not be terminated as retaliation for whistle-blowing activity or for filing a workers’ compensation claim. Workplace Behavior Issues Employees are human beings whose behavior at work is influenced by many factors, including experiences and situations that exist outside the context of the workplace. Regardless of the source, these factors influence the way employees behave while they’re at work. Employee behavior and management’s response (or, in some cases, lack of response) affects the productivity and morale of the entire workgroup and may spill into other parts of the organization. Some employee behaviors that can lead to disciplinary action include the following: Absenteeism Employees call in sick for many different reasons— sometimes they them- selves are ill or perhaps a child or parent needs care. Some employees have been known to call in sick to go surfing, hang out with friends, go shopping, or have a “mental health” day. Regardless of the reasons employees give for absences, more often than not the unan- ticipated absence causes problems for the work group. At the very least, another employee usually must take on additional tasks or responsibilities for the duration of the absence. When one employee has an excessive number of absences that aren’t protected under FMLA, an absentee policy provides the basis for disciplinary action. An effective policy includes a clear statement of how much sick leave is provided, whether each day off work is counted as one absence, or whether several days off in a row for the same illness is consid- ered one absence. The policy should also tell employees whether the absences are counted on a fiscal, calendar, or rolling-year basis, and when a doctor’s note is required before sick leave may be used. Dress Code Dress-code policies let employees know how formal or informal their clothes need to be in the workplace. Some types of clothing may not be appropriate for safety rea- sons (such as to prevent a piece of clothing from getting caught in a machine) or to ensure a professional appearance throughout the organization. A policy should describe what type of clothing is appropriate for different jobs, give examples to clarify, and let employees know the consequences for inappropriate attire. If appropriate, the policy may also describe func- tions or situations in which employees are expected to dress more formally than normal. Insubordination Insubordinate behavior can be as blatant as employees refusing to perform a legitimate task or responsibility when requested by their managers. It can also be subtler, such as employees who roll their eyes whenever a manager gives them direction. It’s not only disrespectful to the manager or supervisor on the receiving end of the behavior, but it can also create morale problems with other members of the work group. Although few organiza- tions have specific policies for insubordination, a code of conduct that describes the organi- zation’s expectations for appropriate behavior, such as treating all employees with dignity and respect, provides managers with the tools they need to correct unacceptable behavior. When discussing performance issues with employees, managers should be encouraged to focus on describing the unacceptable behavior as specifically as possible instead of using general terms such as bad attitude, insubordinate, or poor performance. The more specific the description, the easier it will be for the employee to understand and improve. Specific descriptions of performance issues make any adverse actions easier to defend if an employee decides to take legal action.