EBook For Theology and History in the Methodology of Herman Bavinck Revelation, Confession, and Christian Consciousness 1st Edition By Cameron Clausing

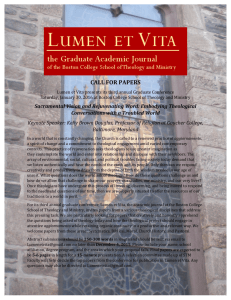

advertisement