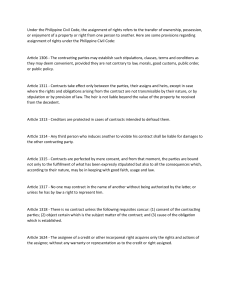

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER CONTRACTS General Provisions ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1305. A contract is a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contract – meeting of the minds between two persons whereby one binds himself with respect to the other to give something or to render some service (Art. 1305, NCC) – A juridical convention manifested in legal form, by virtue of which one or more persons bind themselves in favor of another or others, or reciprocally, to the fulfilment of a prestation to give, to do or not to do (Sanchez Roman) Distinguished from the Special Contract of Marriage Ordinary Contract Marriage As to Parties Parties are two or more The parties must be one persons whether of the man and one woman, both same or different sexes of legal age As to what Governs The nature, consequences The nature, consequences, and incidents of the contract and incidents of the are governed primarily by marriage are governed by the agreement of the parties law As to Result Once executed, the result is Once executed, the result is a contract a status As to Termination Can be dissolved or Cannot be dissolved or terminated by mere terminated by mere agreement of the parties agreement of the parties As to Remedy in Case of Breach The injured party may The injured party may institute an action against institute a civil action the other party for damages against the other party for legal separation or a criminal action for adultery or concubinage Contracts must also not be confused with perfected promises, or to policitacion (imperfect promise) which is a mere unaccepted offer. 73 Contracts must not also be confused with pacts or stipulations. Pact – an incidental part of the contract which can be separated from the principal agreement Stipulation – an essential and dispositive part of the contract (hence, not the contract itself) which cannot be separated from such principal agreement. Elements of Contracts 1. Essential – those without which there can be no contract. Essential elements, in turn are subdivided into: a. Common (communes) – those which are present in all contracts, such as consent of the contracting parties, object certain which is the subject matter of the contract, and cause of the obligation which is established b. Special (especiales) – those which are present only in certain contracts, such as delivery in real contracts or form in solemn ones; and c. Extraordinary or peculiar (especialisimos) – those which are peculiar to a specific contract, such as the price in a contract of sale or insurable interest in a contract of insurance 2. Natural – those which are derived from the nature of the contract and ordinarily accompany the same. They are presumed by law although they can be excluded by the contracting parties if they so desire. Example is warranty against eviction in a contract of sale which is implied although the contracting parties may increase, diminish or even suppress it. 3. Accidental – those which exist only when the parties expressly provide for them for the purpose of limiting or modifying the normal effects of the contract. Parties to a contract – from the definition under Article 1305, it would seem that it is necessary that there must be two persons in order that a contract may exist. This is however not accurate for what is really required is that there must be two different parties. What is therefore necessary is the existence of two distinct and autonomous wills. The existence of a contract is not determined by the number of persons who intervene in it, but by the number of parties thereto. Hence, there are certain cases where a juridical relation, known as an autocontract, may be created wherein, apparently, there MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER is only one party involved, but in reality, said party merely acts in the name and for the account of two distinct contracting parties. Auto-contract may take place (1) when a person, in his capacity as representative of another, contracts with himself, or (2) when as a representative of two different persons, he brings about a contract between his principals by contracting with himself, unless there is conflict of interests or when the law expressly prohibits it in specific cases. Illustration: R is an agent of P for the sale of a parcel of land owned by the latter. P however authorized R to buy for himself the parcel of land if he so desires. In this case, R may enter into a contract of sale wherein R, in a representative capacity, sells to R, in a principal capacity, the parcel of land. This R can do without violating the element of contract which states that there must be two different parties into a contract. The law speaks of two different parties not two persons. Characteristics of Contracts (OMAR) 1. Obligatory force or character of contracts (Articles 1159, 1308, 1315, and 1356) – it refers to the principle that once the contract is perfected, it shall be of obligatory force upon both of the contracting parties. The contracting parties are bound, not only to the fulfilment of what has been expressly stipulated, but also to all the consequences thereof. 2. Mutuality of contracts (Article 1308) – refers to the position of essential equality that is occupied by both contracting parties in relation to the contract. The contract must be binding upon both of the parties. Consequently, its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them 3. Autonomy of contracts (Article 1306) – under this principle, the contracting parties may establish such agreements as they may deem convenient provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. 4. Relativity of contracts (Article 1311) – this principle states that contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs. Consequently, they cannot, as a general rule, produce any effect upon third persons. Life of Contracts 74 1. Generation – comprehends the preliminary or preparation, conception, or generation, which is the period of negotiation and bargaining and ending at the moment of the agreement of the parties. 2. Perfection – the birth of the contract. It is the moment when the parties come to agree on the terms of the contract. 3. Consummation – comprehends the consummation or the death of the contract, which is the fulfilment or performance of the terms agreed upon in the contract. Classification of Contracts 1. According to their relation to other contracts a. Preparatory – those which have for their object the establishment of a condition in law which is necessary as a preliminary step towards the celebration of another subsequent contract (examples: partnership, agency) b. Principal – those which can subsist independently from other contracts and whose purpose can be fulfilled by themselves (examples: sale, lease) c. Accessory – those which can exist only as a consequence of, or in relation with, another prior contract. (examples: guaranty, pledge, mortgage) 2. According to their perfection a. Consensual – those which are perfected by the mere agreement of the parties (examples: sale, lease) b. Real – those which are perfected by the delivery of the object of the obligation (examples: commodatum, deposit, pledge) 3. According to their form a. Common or informal – those which require no particular form (example: loan) b. Special or formal – those which require some particular form (examples: donations, chattel mortgage) 4. According to their purpose a. Transfer of ownership (example: sale) b. Conveyance of use (example: commodatum) c. Rendition of services (example: agency) 5. According to their subject matter a. Things (examples: sale, deposit, pledge) b. Services (examples: agency, lease of services) 6. According to the nature of the vinculum which they produce MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER a. Unilateral – those which give rise to an obligation for only one of the parties (examples: commodatum, gratuitous deposit) b. Bilateral – those which give rise to reciprocal obligations for both parties (examples: sale, lease) 7. According to their cause a. Onerous – those in which each of the parties aspires to procure for himself a benefit through the giving of an equivalent or compensation (example: sale, lease) b. Gratuitous – those in which one of the parties proposes to give to the other a benefit without any equivalent or compensation (example: commodatum) c. Remuneratory – 8. According to the risks involved a. Commutative – those where each of the parties acquires an equivalent of his prestation and such equivalent is pecuniarily appreciable and already determined from the moment of the celebration of the contract (examples: sale, lease) b. Aleatory – those where each of the parties has to his account the acquisition of an equivalent of his prestation but such equivalent, although pecuniarily appreciable is not yet determined at the moment of the celebration of the contract, since it depends upon the happening of an uncertain event, thus charging the parties with the risk of loss or gain (example: insurance) 9. According to their names or norms regulating them a. Nominate – those which have their own individuality and are regulated by special provisions of law (examples: sale, lease) b. Innominate – those which lack individuality and are not regulated by special provisions of law. Breach of Contract Breach of contract – the failure, without legal reason, to comply with the terms of the contract; the failure, without legal excuse, to perform any promise which forms the whole or part of the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1306. The contracting parties may establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Autonomy of Contracts 75 The freedom to contract provided it is not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy, is both a constitutional and a statutory right. Limitations 1. Law – the laws referred to in the article are (1) those which are mandatory or prohibitive in character; (2) those which, without being mandatory or prohibitive, nevertheless, are expressive of fundamental principles of justice, and, therefore cannot be overlooked by the contracting parties; and (3) those which impose essential requisites without which the contract cannot exist. Illustration: S sold to B 20 kilograms of marijuana. In this case the object of the contract or the sale itself is prohibited by law. Since the sale is prohibited by law, the contract of sale here between S and B is invalid. Illustration: D acquired a loan of P 50,000.00 from C. The loan is secured by a property owned by D. However, under the stipulations of the contract, C will acquire the property constituted as security if D failed to pay the loan. The contract in this case is invalid as it is against the law. The stipulation of the parties partake the nature of a pactum commissorium which is prohibited by law. 2. Morals – those principles which are incontrovertible and are universally admitted and which have received social and practical recognition. Illustration: D acquired a loan of P 1,000.00 from C payable within two months. The parties stipulated that D will pay P 20.00 a day in case of non-payment of the debt at maturity. The stipulation in this case is void for being contrary to morals as the penalty is clearly excessive, unconscionable, and shocking to the senses. However, in this case, what is void is the stipulation to pay the penalty and not the principal contract. The stipulation to pay the penalty in this case shall be deemed not have been agreed upon. 3. Good customs – the spheres of morals and good customs frequently overlap each other but sometimes they do not. It must be admitted however that if a moral precept pr custom is not recognized universally, but is sanctioned by the practice of a certain community, then it shall be included within the scope or sphere of good customs. 4. Public order – public order can only refer to the safety, as well as to the peace and order, of the MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER country or of any particular community. Public order is not as broad as public policy. The latter may refer not only to public safety but also to considerations which are moved by the common good. 5. Public policy – a principle of law which holds that no person can lawfully do that which has a tendency to be injurious to the public or against the public good. Illustration: T stole goods belonging to O. T was however caught. T and O agreed that O will stifle (suppress) the prosecution of T if T will give him P 10,000.00. The agreement in this case is against public policy and therefore void. Illustration: Bus Co., a bus company, posted notices that the bus will not be liable for any loss or damage to passengers or their properties occasioned by their own negligence, and that the passengers will be deemed to have accepted the condition upon buying a bus ticket and boarding their bus. The agreement in this case is invalid for being contrary to public policy. Common carriers cannot escape liability by posting notices that they will not be liable for any loss to their passengers by reason of their (Bus Co.) own negligence. Compromise Agreements; effects Compromise – a contract whereby the parties, by making reciprocal concessions, avoid a litigation or put an end to one already commenced. It is an agreement between two or more persons, who, for preventing or putting an end to a lawsuit, adjusts their difficulties by mutual consent in the manner which they agree on, and which everyone of them prefers in the hope of gaining, balanced by the danger of losing. General rule: a compromise has upon the parties the effect and authority of res judicata, with respect to the matter definitely stated therein, or which by implication from its terms should be deemed to have been judicially approved. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1307. Innominate contracts shall be regulated by the stipulations of the parties, by the provisions of Titles I and II of this Book, by the rules governing the most analogous nominate contracts, and by the customs of the place. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Nominate and Innominate Contracts 76 Nominate Contracts – those which have their own distinctive individuality and are regulated by special provisions of law. (ex. Sale, Barter of Exchange, Lease, Partnership, Agency, Loan, Deposit, Aleatory contracts, Compromise and Arbitration, Guaranty, Pledge, Mortgage, and Antichresis Innominate Contracts – those which lack individuality and are not regulated by special provisions of law. Kinds of Innominate Contracts a. Do ut des – I give and you give b. Do ut facias – I give and you do c. Facio ut des – I do and you give d. Facio ut facias – I do and you do ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1308. The contracts must bind both contracting parties; its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them. Art. 1309. The determination of the performance may be left to a third person, whose decision shall not be binding until it has been made known to both contracting parties. Art. 1310. The determination shall not be obligatory if it is evidently inequitable. In such case, the courts shall decide what is equitable under the circumstances. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Mutuality of Contracts The validity or fulfilment of a contract cannot be left to the will of one of the contracting parties. It must be observed however that what is prohibited by law from being delegated to one of the contracting parties are: 1. The power to determine whether the contract shall be valid; and 2. The power to determine whether the contract shall be fulfilled. Illustration: L and O entered into a contract of lease whereby O leased to L the former’s house. It was stipulated in the contract that L can continue occupying the house indefinitely as long as they should faithfully fulfil their obligation to pay rentals. In this case, the characteristic of mutuality is violated. The continuance and fulfilment of the contract would depend solely and exclusively upon L’s uncontrolled choice between continuing paying the rentals or not, completely depriving O of all say on the matter. However, there are certain agreements which will in effect render the mutuality of contracts illusory MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER because one of the contracting parties is placed in a position of superiority with regard to the determination of the validity or fulfilment of the contract over that occupied by the other party, but which do not fall within the purview of the prohibition under Article 1308. Determination by Third Person or by Chance – The validity or fulfilment may be left to the will of a third person. However, it is necessary that the determination made by the third person should not be evidently inequitable. If it is evidently inequitable, it shall not have any obligatory effect upon the contracting parties. The validity or fulfilment can also be left to chance When Stipulated – it is important to note however that an agreement of the parties that either one of them may terminate the contract upon reasonable period of notice is valid. Judicial action for the rescission of a contract is not necessary where the contract provides that it may be revoked and cancelled for the violation of any of its terms and conditions. This right of rescission, however, may be waived. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1311. Contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs, except in case where the rights and obligations arising from contract are not transmissible by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. The heir is not liable beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent. If a contract should contain some stipulation in favor of a third person, he may demand its fulfilment provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. A mere incidental benefit or interest or a person is not sufficient. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Relativity of Contracts A contract can only bind the parties who had entered into it or their successors who have assumed their personality or their juridical position, and that, as a consequence, such contract can neither favor nor prejudice a third person (in conformity with the axiom res inter alios acta aliis neque nocet prodest) General rule: contracts can take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs. 77 Exceptions: An assignee or heir shall not be bound by the terms of the contract if the rights and obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible: 1. By their nature, as when the special or personal qualification of the obligor constitutes one of the principal motives for the establishment of the contract; or 2. By stipulation of the parties, as when the contract expressly provides that the obligor shall perform an act by himself and not through another; or 3. By provision of law, as in the case of those arising from a contract of partnership or of agency Effect of Contract on Third Persons – As a general rule, a contract cannot produce any effect whatsoever as far as third persons are concerned. Consequently, he who is not a party to a contract, or an assignee thereunder, has no legal capacity to challenge its validity. Exceptions: 1. Where the contract contains a stipulation in favor of a third person; 2. Where the third person comes into possession of the object of a contract creating a real right; 3. Where the contract is entered into in order to defraud a third person; and 4. Where the third person induces a contracting party to violate his contract Stipulations in Favor of Third Persons (Stipulation pour autrui) Stipulation pour autrui – a stipulation in a contract, clearly and deliberately conferred by the contracting parties as a favor upon a third person, who must have accepted it before it could be revoked. Kinds of Beneficial Stipulations in Favor of Third Persons 1. Those where the stipulation is intended for the sole benefit of the third person; and 2. Those where an obligation is due from the promise to the third person which the former seeks to discharge by means of such stipulation. Requisites (FP-CAN) 1. There must be a stipulation in favor of a third person; 2. The stipulation must be a part, not the whole, of the contract; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 3. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person, not a mere incidental benefit or interest; 4. That the favorable stipulation should not be conditioned or compensated by any kind of obligation whatever; 5. The third person must have communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation; and 6. Neither of the contracting parties bears the legal representative or authorization of the third party The acceptance by the third person or beneficiary does not have to be done in any particular form. It may be done expressly or impliedly. Illustration: Insurance Co. issued in favor of Bus Co. an accident insurance policy for a period of 1 year. It was stipulated in the policy that Insurance Co. will indemnify Bus Co. in the event of accident against all sums which the insured (Bus Co.) will become legally liable to pay for death or injury to any fare-paying passenger, driver, conductor, or inspector, who is riding the vehicle at the time of the accident. In this case, the heirs of D, a driver of Bus Co. may sue Insurance Co. and demand the fulfilment of the contract in case D died in an accident while driving a bus owned by Bus Co. notwithstanding the fact that D is not a party to the contract. The stipulation in this case is a stipulation pour autrui. (Note: the heirs of D may sue by virtue of relativity of contracts). A stipulation may validly be made in favor of indeterminate persons, provided that they can be determined in some manner at the time when the prestation from the stipulation has to be performed. The stipulation can also be in favor of future persons, or one who is to be born after perfection of the contract containing the stipulation. The acceptance is optional upon the third person Test of Beneficial Stipulation – The test is to rely upon the intention of the parties as disclosed by their contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1312. In contracts creating real rights, third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby, subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contract Creating Real Rights 78 A real right is a right belonging to a person over a specific thing, without a passive subject individually determined, against whom such right may be personally enforced. Consequently, a third person who might come into possession of the object of a contract creating real right will have to be bound by such right subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. Illustration: A mortgaged his house and lot to the PNB in order to secure an obligation of P 50,000.00. The mortgage is registered in the Registry of Property. The effect of such of registration is to create a real right which will be binding against the whole world. Hence, if A subsequently sold the property to S, the contract of mortgage between A and PNDB will be binding upon S. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1313. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contracts in Fraud of Creditors A third person who is a creditor of one of the contracting parties may ask for the rescission of the contract if it can be established that the contract was entered into with the intention of defrauding him. However, it is necessary to proved that such creditor has no other legal means to obtain reparation. Illustration: On December 25, 2011, D borrowed P 50,000.00 from C payable on February 25, 2012. Upon maturity, C demanded payment of the debt but D refused to pay. On February 28, 2012, D donated a parcel of land to X. In this case, C may ask for the rescission of the contract between D and X. However, C must first establish that no other legal remedy is available to him in order that D’s obligation to him is to be satisfied. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1314. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Doctrine of Contractual Interference A third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. The right to perform a contract and to reap the profits resulting from such performance, and also the right to performance by the other party, are property rights which MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER entitle each party to protection and to seek compensation by an action in tort for any interference therewith. Requisites 1. There is a valid contract; 2. The third person has knowledge of the existence of the valid contract; and 3. There is interference by such third person without legal justification or excuse Illustration: Sharon is an actress. Sharon and TV5 entered into a contract whereby Sharon shall be exclusively a TV5 actress for a period of 5 years in consideration of P 1,000,000,000.00. Before the expiration of the contract, GMA7 induced Sharon to violate her contract with TV5 by appearing in GMA7 shows, without the consent of TV5. In this case, GMA7 is liable for damages in favor of TV5. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1315. Contracts are perfected by mere consent, and from that moment the parties are bound not only to the fulfilment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law. Art. 1316. Real contracts, such as deposit, pledge and commodatum, are not perfected until the delivery of the object of the obligation. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Perfection of Contracts Perfection of a contract refers to that moment in the life of the contract when there is finally a concurrence of the wills of the contracting parties with respect to the object and the cause of the contract. General rule: contracts are perfected by mere consent. Exceptions: real contracts. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person in whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contracts in Name of Another 79 The principle enunciated in Article 1317 is a logical corollary to the principles of the obligatory force and the relativity of contracts. The contract illustrated by the second paragraph is an unenforceable contract or one which cannot be enforced by a proper action in court, unless they are ratified, because either they are entered into without or in excess of authority. The effect of the ratification is retroactive. Hence, ratification validates the contract from the moment of its celebration, and not merely from the time of its ratification. If the contract is not ratified by the person represented, the representative becomes liable in damages to the other party. Essential Requisites of Contracts General Provisions ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1318. There is no contract unless the following requisites concur: 1. Consent of the contracting parties; 2. Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; 3. Cause of the obligation which is established. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Common Essential Elements The elements of contracts enumerated under Article 1318 are those which are referred to us common essential elements. As already stated, common essential elements are those elements which are present in all contracts and without which there can be no contract. The law imposes the essential elements (not just the common essential elements), presumes the natural, and authorizes the accidental. The will of the contracting parties conforms to the essential, accepts or repudiates the natural, and establishes the accidental. Consent ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1319. Consent is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The offer must be MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER certain and the acceptance absolute. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. Acceptance made by letter or telegram does not bind the offerer except from the time it came to his knowledge. The contract, in such a case, is presumed to have been entered into in the place where the offer was made. Art. 1320. An acceptance may be express or implied. Art. 1321. The person making the offer may fix the time, place, and manner of acceptance, all of which must be complied with. Art. 1322. An offer made through an agent is accepted from the time acceptance is communicated to him. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Consent Consent – the concurrence of the wills of the contracting parties with respect to the object and the cause which shall constitute the contract. In its derivative sense, consent means the agreement of wills. Requisites of Consent (CC-IFSR) 1. Consent must be manifested by the concurrence of the offer and the acceptance 2. The contracting parties must possess the necessary legal capacity 3. Consent must be intelligent, free, spontaneous, and real Perfection of Contracts In general, contracts are perfected from the moment that there is a manifestation of the concurrence between the offer and the acceptance with respect to the object and the cause which shall constitute the contract. However, if the acceptance is made by letter or telegram: General rule: the contract is perfected from the moment that the offeror has knowledge of such acceptance (Art. 1319, par. 2) Exception: In purely commercial contracts, such as joint accounts, maritime contracts, etc. contract is perfected from the moment an answer is made accepting the offer (Art. 54, Code of Commerce) It must be noted that before there is consent, it is essential that it must be manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. Once there 80 is such a manifestation of the concurrence of the wills of the contracting parties, the period or stage of negotiation is terminated. The contract, if consensual, is finally perfected. Character of Offer and Acceptance Offer – a proposal to make a contract; a unilateral proposition which one party makes to the other contracting party for the celebration of the contract. In order to constitute a binding proposal, the offer must be certain or definite. Requisites of Offer 1. Definite – the offer must be definite, so that upon acceptance an agreement can be reached on the whole contract. 2. Complete – the offer must be complete indicating with sufficient clearness the kind of contract intended and definitely stating the essential conditions of the proposed contract, as well as the non-essential ones desired by the offeror. 3. Intentional – an offer without seriousness made in such manner that the other party would not fail to notice such lack of seriousness, is absolutely without juridical effects and cannot give rise to a contract. Illustration: A, in a letter, told B that the former is willing to entertain the purchase of a house belonging to B. In this case, the acceptance by B will not result in a perfected contract as the offer of A to buy is not definite. Illustration: A offered to B the sale of an animal. In this case, the acceptance by B would not result in a perfected contract as the offer was not complete. The object of the contract, which is an essential element, is not clear. Illustration: A told B that the former will give the latter the moon in consideration of P 1,000,000.00. In this case, it is obvious that the offer was not serious. A visited the house of B. B, in welcoming A, told A that “my house is yours.” In this case, the acceptance by B would not result in a perfected contract (donation in this case) as the offer was merely a customary way of accepting guests (Also, donation of immovables must be in a public document). MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Withdrawal of Offer – the offeror may still withdraw his offer so long as he still has no knowledge of the acceptance by the offeree. Illustration: A, through a letter, told B that he is offering his house for sale for P 500,000.00. The letter is to be received by B the following day. The following day, B received the letter and thereafter wrote a reply stating his acceptance. The letter of acceptance is to be received by A the following day. However, A changed his mind and he is not willing to sell his house anymore. Hence, a day after he wrote his letter-offer (same day when B accepted the offer), A called B using a telephone and told him that he is withdrawing his offer. The withdrawal in this case is valid because the acceptance made by B has not come to the knowledge of A yet. Hence, at the time of the withdrawal, there is no perfected contracted yet. Acceptance – the signification of the assent of the offeree to the proposition of the offeror. Acceptance may be express or implied. Implied acceptance – implied acceptance may arise from acts or facts which reveal the intent to accept, such as the consumption of the things sent to the offeree. Lapse of Time – an offer without a period must be considered as becoming ineffective after the lapse of more than the time necessary for its acceptance, taking into account the circumstances and social conditions. Requisites of Acceptance 1. Certain or definite 2. Absolute or unconditional 3. Directed to the offeror 4. Made known to the offeror within a reasonable time 5. Communicated to the offeror and learned by him Illustration: A told B that he is offering his house for sale for P 1,000,000.00. B accepted but told A if he can reduced the price to P 850,000.00. In this case there is no perfected contract. The “acceptance” by B is not absolute. Illustration: A, through a letter, told B that he is offering his car for sale for P 100,000.00. Upon reading the letter, B said “Yes! I accept!” but B did not write a reply stating his acceptance nor called A to say his acceptance. In this case there is no perfected 81 contract. Perfection of contract requires the concurrence of offer and acceptance. There is no concurrence of offer and acceptance if the acceptance is not made known to the offeror. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. Consequently, when something is desired which is not exactly what is proposed in the offer, such acceptance is not sufficient to generate consent because any modification or variation from the terms of the offer annuls the offer. Right of the Offeror – the offeror has the right to prescribe the manner, conditions, and terms of the contract, and where these are reasonable and are made known to the offeree, they are binding upon the latter; an acceptance which is not made in the manner prescribed by the offeror is not effective, but constitutes a counter-offer which the offeror may accept. Acceptance of Complex Offers – to a certain extent the rules regarding acceptance are modified in case of complex offers. Illustration: S offered to sell Blue House and to lease Red House (both houses are owned by A) to B. B accepted the sale of Blue House. There is a perfected contract of sale in this case as its acceptance is not dependent upon the acceptance of the contract of lease. However, if S told B that he is not willing to sell Blue House if B would not also lease Red House, then there is no perfected contract of sale. The sale was made to depend upon the acceptance of the lease as well. However, the prospective contracts which are comprised in a single offer may be so interrelated in such a way that the acceptance of one would not at all result in a perfected contract. Illustration: D asked C if the latter could extend to the former a loan for P 50,000.00. C told D that he is, provided that a mortgage to secure the proposed loan is constituted. D accepted the loan but not the mortgage. In this case there is no perfected contract of loan. The acceptance of the mortgage is an essential condition for the perfection of the loan in this case. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Withdrawal of Acceptance – acceptance may be revoked before it comes to the knowledge of the offeror because in such a case there is still no meeting of the minds. Acceptance by Letter or Telegram (MERC) 1. Manifestation theory – contract is perfected from the moment the acceptance is declared or made (followed by the Code of Commerce) 2. Expedition theory – the contract is perfected from the moment the offeree transmits the notification of acceptance to the offeror, as when the letter of acceptance is place in the mailbox. 3. Reception theory – the contract is perfected from the moment that the notification of acceptance is in the hands of the offeror in such a manner that he can, under ordinary conditions, procure the knowledge of its contents, even if he is not able to actually acquire such knowledge due to some reason. 4. Cognition theory – the contract is perfected from the moment the acceptance comes to the knowledge of the offeror (followed by the Civil Code) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1323. An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before acceptance is conveyed. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Effect of Death, Civil Interdiction, Insanity, or Insolvency An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before the offeror has knowledge of the acceptance by the offeree. The word “conveyed” in the article refers to that moment when the offeror has knowledge of the acceptance by the offeree. Illustration: S called B and offered to the latter the sale of the former’s car for P 500,000.00. B could not accept that time so he asked S some time to think about it which S granted. 2 days thereafter, B decided to accept the offer. Thus, he wrote a letter of acceptance. The letter is to be received by S the following day. However, upon mailing the letter, a speeding car hit B causing his death. In this case there is no perfected contract of sale as one of the parties (B, the offeree) died before acceptance is conveyed to the offeror. Hence, the heirs of B cannot compel S to sell the car and invoke the relativity of contracts as there is no contract to speak of in the first 82 place. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1324. When the offeror has allowed the offeree a certain period to accept, the offer may be withdrawn at any time before acceptance by communicating such withdrawal, except when the option is founded upon a consideration, as something paid or promised. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Option Contract Option Contract – a preparatory contract in which one party grants to the other, for a fixed period and under specified conditions, the power to decide whether or not to enter into a principal contract. It must be supported by an independent consideration and the grant must be exclusive Like other contracts, an option contract must be supported by a consideration which is separate and distinct from the consideration in the principal contract (i.e., sale). If the option is without a separate consideration, it is void as a contract. Consequently, the promissor-offeror is not bound by his promise and may, accordingly, withdraw it. However, pending notice of his withdrawal, his promise partakes of the nature of a continuing offer which, if accepted before withdrawal, results in the perfection of the principal contract. Illustration: S offered to B his car for P 500,000.00. As B had insufficient funds at that moment, he asked S if he could give him a time to think about it. S granted the request and granted B an option to buy the car for 2 months in consideration of P 1,000.00. B accepted the option but did not pay the P 1,000.00. Before the expiration of the 2-month period, B told S that he is accepting the offer to buy the car. In this case, the contract of the sale of the car is already perfected. This is true notwithstanding that the option contract is void for lack of separate consideration. His promise partake the nature of a continuing offer. Illustration: S offered to B his car for P 500,000.00. As B had insufficient funds at that moment, he asked S if he could give him a time to think about it. S granted the request and granted B an option to buy the car for 2 months in consideration of P 1,000.00. B accepted the option but did not pay the P 1,000.00. Before the expiration of the 2-month period and before acceptance by B, S withdrew the offer to sell the car. The withdrawal of the offer in this case is valid. B cannot invoke the option granted to him by S MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER as the same was void. Withdrawal of Offer under a Valid Option There are two conflicting views as regards this subject matter: First view: if the option is founded upon a separate consideration (and therefore valid), the offeror cannot withdraw the principal offer. Second view: in an option contract, with or without a separate consideration, the offeror may still withdraw the principal offer, provided the withdrawal is made before the acceptance of the principal offer. This is because there is no perfected principal contract yet. However, if the option is with a separate consideration, the offeror shall be liable for damages. In this case, the offeree cannot compel the offeror to enter into the principal contract. To do so would partake to an “obligation to do” or personal obligation. In a personal obligation, the debtor cannot be compelled to comply with his obligation. The only remedy of the obligee is to file an action for damages against the obligor. The case should be distinguished to a case where acceptance of the principal contract was made known to the offeror before the withdrawal. In this case there is already a perfected principal contract. The obligee can therefore compel the obligor (offeror) to comply with his obligation under the principal contract (except of course if the prestation under the principal contract consists in an obligation to do) The second view is more in accordance with the principles of contract. Illustration: S offered to B his car for P 500,000.00. As B had insufficient funds at that moment, he asked S if he could give him a time to think about it. S granted the request and granted B an option to buy the car for 2 months in consideration of P 1,000.00. B accepted the option and paid the P 1,000.00. However, before the expiration of the 2-month period, S sold the car to X. In this case the withdrawal of the offer to sell the car is valid as there was no perfected contract of sale notwithstanding the existence of a valid option contract. However, S is liable for damages in favor of B. Option Contract Distinguished 83 and Right of First Refusal, Option Contract Can stand on its own (principal contract) Requires a separate consideration distinct from that of the principal contract in order to be valid Not conditional Not subject to specific performance since there is no perfected principal contract yet. Right of First Refusal Cannot stand on its own (accessory contract) Does not require a separate consideration Conditional Can be subjected to specific performance Option Money and Earnest Money, Distinguished Option Money Earnest Money Money given as a distinct Money which is part of the consideration for an option purchase price contract Applies to contract of sales Applies to contract of sales not yet perfected already perfected The would-be buyer who The buyer who gives the gives the option money is earnest money is bound to not bound to buy pay the balance ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1325. Unless it appears otherwise, business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. Art. 1326. Advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals, and the advertiser is not bound to accept the highest or lowest bidder, unless the contrary appears. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Sales Advertisements A business advertisement of things for sale may or may not constitute a definite offer. It is not a definite offer when the object is not determinate. When the advertisement does not have the necessary specification of essential elements of the future contract, it cannot constitute an offer. Illustration: While watching her television, A chanced upon a shampoo commercial by Pantene. The advertisement stated the suggested retail price of a sachet of a Pantene shampoo. In this case, the advertisement is merely an invitation to make an offer because although the suggested retail price was specified (and this is true even if the actual price, not merely suggested, was shown) because the quantity MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER to be sold was absent. The advertiser therefore is free to reject any offer that may be made. Illustration: While reading an issue of Philippine Daily Inquirer, A saw an advertisement which read states: “For sale, 500 m2 lot located at Mendiola, Manila corner J.P. Laurel street (just beside San Beda College) for P 1,000,000.00. Just contact “Acong” at 800-6969.” In this case the offer is definite. A may call Acong and tell the latter that he (A) is accepting the offer. Illustration: Hotel Co. published in a newspaper an “Invitation to Bid” inviting proposals to supply labor and materials for a construction project described in the invitation. A Co., B Co., and C Co. C Co. submitted the lowest bid. However, Hotel Co. awarded the contract to A Co. on the ground that he was the most experienced and responsible bidder. In this case, C Co. cannot compel Hotel Co. to award the contract in its favor. The awarding of the contract in favor of A Co. was within the rights of Hotel Co. as the general rule that advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals. It would have been different if in the advertisement, it was clearly stated that the lowest (or highest) bidder shall be awarded the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1327. The following cannot give consent to a contract: 1. Unemancipated minors; 2. Insane or demented persons, and deaf-mutes who do not know how to write. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Legal Capacity of Contracting Parties The capacity of the contracting parties is an indispensable requisite of consent. Incapacitated Persons – contracts entered into by the following incapacitated persons are voidable, if only one of the contracting parties is incapacitated, or unenforceable if both contracting parties are incapacitated to give consent to a contract. the action for annulment cannot be instituted by the person who is capacitated since he is disqualified from alleging the incapacity of the person whom he contracts. 1. Minors – by virtue of Article 234 of the Family Code, which states that: “Emancipation takes place by the attainment of majority. Unless otherwise provided, 84 majority commences at the age of eighteen years.” the “unemancipated minors” referred to in Article 1327 merely pertains to “minors” as there can be no “emancipated minors” in this jurisdiction anymore. A minor is without capacity to give consent to a contract, and since consent is an essential requisite of every contract, the absence thereof cannot give rise to a valid contract. The contract in this case is a voidable contract (unless the other contracting party is also incapacitated to give consent, in which case the contract is unenforceable). Exceptions: i. Where the contract involves the sale and delivery of necessaries to the minor. Requisites: 1. Perfection of the contract (sale); 2. Delivery of the subject matter. Necessaries – necessaries are those which are indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. ii. Where the contract is entered into by a minor who misrepresents his age, applying the doctrine of estoppel. iii. When it involves a natural obligation and such obligation is fulfilled voluntarily by the minor, provided that such minor is between eighteen and twenty-one years of age (No longer applicable as an exception) iv. When it is a marriage settlement or donation propter nuptias, provided that the minor is between twenty and twenty-one years of age, if male, or between eighteen and twenty-one years of age, if female (No longer applicable as an exception) v. When it is a life, health, or accident insurance taken on the life of the minor, provided that the minor is eighteen years old or more and the beneficiary appointed is the minor’s estate, or the minor’s father, mother, husband, wife, child, brother, or sister (No longer applicable as an exception) 2. Insane or demented persons – any person, who, at the time of the celebration of the contract, cannot understand the nature and consequences of the act or transaction by reason of any cause affecting his MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER intellectual or sensitive faculties, whether permanent or temporary. However, a contract entered into during a lucid interval is valid. In order to avoid a contract because of mental incapacity, it is necessary to show that at the time of the celebration of the contracting parties was not capable of understanding with reasonable clearness the nature and effect of the transaction in which he was engaged. Hence, such circumstances as age, sickness, or any other condition as such will not necessarily justify a court of justice to interfere in order to set aside a contract voluntarily entered into. Mental incapacity to enter into a contract is a question of fact which must be decided by the courts. There is however a prima facie presumption that every person of legal age possesses the necessary capacity to execute a contract. 3. Deaf-mutes who do not know how to write – the case must be distinguished from a contract entered into by a deaf-mute who knows how to write, which is perfectly valid. On the other hand, contracts entered into by a deaf-mute who do not know how to write may either be voidable or unenforceable. 4. Other Incapacitated Persons a. Married women in cases specified by law; b. Persons suffering from civil interdiction; c. Incompetents who are under guardianship “Incompetents” include: i. Persons suffering from civil interdiction (does not require guardianship to be incapacitated); ii. Hospitalized lepers; iii. Prodigals; iv. Deaf and dumb who are unable to read and write (deaf-mutes who do not know how to write does not require guardianship to be incapacitated); v. Those who are of unsound mind, even though they have lucid intervals (insane or demented persons does not require guardianship to be incapacitated); vi. Those who by reason of age, weak mind, and other similar causes, cannot, without outside aid, take care of themselves and 85 manage their property becoming thereby an easy prey for deceit and exploitation. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1328. Contracts entered into during a lucid interval are valid. Contracts agreed to in a state of drunkenness or during a hypnotic spell are voidable. Art. 1329. The incapacity declared in Article 1327 is subject to the modification determined by law, and is understood to be without prejudice to special disqualifications established by laws. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Disqualifications to Contract Persons specially disqualified are those who are prohibited from entering into a contract with certain persons with regard to certain property under certain circumstances and not to those who are incapacitated to give their consent to a contract. Incapacity and Disqualification, Distinguished Incapacity Disqualification (Absolute Incapacity) (Relative Incapacity) As to Nature Impairs the exercise of the Prohibition to contract right to contract; the restrains the very right itself; incapacitated person may the disqualified person still enter into a contract but cannot enter into a contract with consent of his parent or with respect to certain types guardian of properties As to Basis Based upon subjective Based upon public policy circumstances of certain and morality persons which compel the law to suspend for a definite period, their right to contract As to Defect Contract entered into by an Contract entered into by a incapacitated person is disqualified person is void merely voidable Disqualified Persons – contracts entered into in the following cases by the following persons are void (not merely voidable). 1. Spouses – the spouses cannot donate properties to each other except donation of moderate gifts on the occasion of any family rejoicing (Art. 87, Family Code). The spouses cannot also sell property to each other, except when a separation of property was agreed upon in the marriage settlements, or when MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER there has been a judicial separation of property (Art. 1490) Prohibition applies to common-law spouses. Contracts entered into in violation of Article 1490 of the Civil Code (and Article 87 of the Family Code) are null and void (not merely voidable). However, not anyone is given the right to assail the validity of the transaction Examples of Persons who cannot assail the Validity of Contracts in Violation of the Prohibition: a. The spouses themselves cannot assail the validity of the contract since they are parties to an illegal act under the principle of pari delicto, the courts will generally leave them as they are. b. The creditors who became such only after the transaction (the illegal contract of sale), for it cannot be said that they have been prejudiced by the transaction Persons who can assail the Validity of Contracts in Violation of the Prohibition: a. The heirs of either of the spouses who have been prejudiced b. Creditors who became such prior to the transaction c. The State when it comes to payment of the proper taxes due on the transaction 2. Guardians with respect to the property of the person under guardianship – Prohibition applies even if the guardian did not acquire the property of the ward from the ward directly as when there was a third person who bought the property from the ward and that third person sold the property in question to the guardian Illustration: G, guardian of W, purchased a property worth P 1,000,000.00 owned by W for P 10,000,000.00. In this case, the purchased is void notwithstanding the fact that in the said contract is more beneficial to W. The prohibition is absolute. 3. Agents with respect to property to whose administration or sale may have been entrusted to them Exception: when the consent of the principal has been given. An agent of a principal is not automatically disqualified from acquiring property from the principal. For the prohibition to apply, the property which is the subject 86 of the contract must be the property entrusted to the principal. Hence if the principal owns two parcels of land and the agent was entrusted with one these properties, the agent can acquire from the principal the other property Illustration: Boy Abunda is a talent agent of Kris Aquino. Kris Aquino sold one of her houses to Boy Abunda. The contract in this case is valid as Boy Abunda is not the “agent” as referred to in the prohibition. Illustration: O owns two parcels of land, L1 and L2. O entrusted to A, agent, the sale of L1. A purchased from O L2. The sale in this case is valid because A has not been entrusted with the sale of the property he acquired (L1 is what has been entrusted to him, not L2 which is the one he purchased). It would have been different if the administration or sale of L2 has also been entrusted to A. 4. Executors and Administrators with respect to the property of the estate under administration Note: But an executor can acquire the hereditary rights of an heir to the estate under his administration 5. Public Officers and Employees with respect to the property of the State or any of its subdivisions, any Government-owned and controlled corporations, or institution the administration of which has been entrusted to them 6. Justices, judges, prosecuting attorneys and other court officers and employees connected with the administration of justice with respect to property and rights in litigation or levied upon on execution before the court within whose jurisdiction or territory they exercise their respective functions The object is considered in litigation upon filing of an answer. The property is in litigation from the moment it became subject to the judicial action of the judge, such as levy on execution 7. Lawyers – Prohibition applies only to a sale to a lawyer of record, and does not cover assignment of the property given in judgment made by a client to an attorney, who has not taken part in the case nor to a lawyer who acquired property prior to the time he intervened as counsel in the suit involving such property Exceptions to prohibition: MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER a. To sale of a land acquired by a client to satisfy a judgment in his favor, to his attorney as long as the property was not the subject of the litigation; or b. To a contingency fee arrangement which grants the lawyer of record proprietary rights to the property in litigation since the payment of said fee is not made during the pendency of litigation but only after judgment has been rendered 8. Aliens – aliens are disqualified from acquiring agricultural lands (Secs. 3 and 7, Art. XII, 1987 Constitution). “agricultural lands” should not be interpreted literally. Under the Constitution, only agricultural lands may be alienated. Hence, “agricultural lands” are those lands which can be alienated and hence does not include lands of the public domain. Thus, a land is “agricultural land” even if it is located in an industrial center or is used for residential purposes as long as it does not belong to the public domain. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1330. A contract where consent is given through mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud is voidable. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Vices of Consent Intelligent consent is vitiated by mistake or error; free consent by violence, intimidation, and undue influence; spontaneous consent by fraud. a. Vices of the will – comprehends mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, and fraud. b. Vices of declaration – comprehends all forms of simulated contracts. Defect or lack of valid consent, in order to make the contract voidable, must be established by full, clear, and convincing evidence, and not merely by a preponderance thereof. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1331. In order that mistake may invalidate consent, it should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract. Mistake as to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties will vitiate consent only when such identity or 87 qualifications have been the principal cause of the contract. A simple mistake of account shall give rise to its correction. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Mistake Mistake – mistake is not only the wrong conception of a thing, but also the lack of knowledge with respect to a thing. Kinds of Mistake a. Mistake of Fact – when one or both of the contracting parties believe that a fact exists when in reality it does not or that such fact does not exist when in reality it does. This is the mistake which vitiates consent. b. Mistake of Law – when one or both of the contracting parties arrive at an erroneous conclusion regarding the interpretation of a question of law or the legal effects of a certain act or transaction. Different Kinds of Mistakes of Fact 1. Mistake as to Object (error in re) – mistake which is referred to in the first paragraph of Article 1331. a. Mistake as to the identity of the thing (error in corpore), as when the thing which constitutes the object of the contract is confused with another thing; b. Mistake as to the substance of the thing (error in substantia); c. Mistake as to the conditions of the thing, provided such conditions have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract; and d. Mistake as to the quantity of the thing (error in quantitate), provided that the extent or the dimension of the thing was the principal reasons of one or both of the parties for entering into the contract. It is necessary that such mistake should refer not only to the material out of which the thing is made, but also to the nature which distinguishes it, generally or specifically, from all others, such as when a person purchases a thing made of silver believing that is made of gold. If mistake refers only to accidental or secondary qualities (error in qualitate), the contract is not rendered voidable. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 2. Mistake as to Person (error in persona) – mistake which may refer either to the name or to the identity or to the qualification of a person. Requisites: i. The mistake must be either with regard to the identity or with regard to the qualification of one of the contracting parties; ii. Such identity or qualification must have been the principal consideration for the celebration of the contract. The only mistake with regard to persons which will vitiate consent are mistakes with regard to the identity or the qualifications of one of the contracting parties. Hence, mistake with regard to the name of one or both of the contracting parties will not invalidate the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1332. When one of the parties is unable to read, or if the contract is in a language not understood by him, and mistake or fraud is alleged, the person enforcing the contract must show that the terms thereof have been fully explained to the former. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rule where a Party is Illiterate In the cases contemplated under Article 1332, the burden of proving that the plaintiff had understood the contents of the document was shifted to the defendant and he had failed to do so, the presumption of mistake still stands unrebutted and controlling. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1333. There is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract. Art. 1334. Mutual error as to the legal effect of an agreement when the real purpose of the parties is frustrated, may vitiate consent. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Mistake of Law As a rule, mistake of law will not vitiate consent. However, mutual error as to the effect of an agreement when the real purpose of the parties is frustrated, may vitiate consent. In other words, when there is mistake on a doubtful question of law, or on the construction or application of law, this is analogous to a mistake of fact, and the maxim of ignorantia legis neminem excusat should have no proper application. Requisites: 88 1. The mistake must be with respect to the legal effect of an agreement; 2. The mistake must be mutual; and 3. The real purpose of the parties must have been frustrated. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1335. There is violence when in order to wrest consent, serious or irresistible force is employed. There is intimidation when one of the contracting parties is compelled by a reasonable and well-grounded fear of an imminent and grave evil upon his person or property, or upon the person or property of his spouse, descendants or ascendants, to give his consent. To determine the degree of the intimidation, the age, sex and condition of the person shall be borne in mind. A threat to enforce one’s claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. Art. 1336. Violence or intimidation shall annul the obligation, although it may have been employed by a third person who did not take part in the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Violence and Intimidation Violence and intimidation are sometimes known as duress. Violence Intimidation As to type of Compulsion Physical compulsion. Moral compulsion. Hence, Hence, violence is external. intimidation is internal. As to Effect Violence prevents the Intimidation influences the expression of the will operation of the will, substituting it with a material inhibiting it in such a way act dictated by another that the expression thereof is apparently that of a person who has freely given his consent. Requisites of Violence: 1. The force employed to wrest consent must be serious or irresistible; and 2. It must be the determining cause for the party upon whom it is employed in entering into the contract. Requisites of Intimidation: 1. One of the contracting parties is compelled to give his consent by a reasonable and well-grounded fear of an evil; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 2. The evil must be imminent and grave; 3. The evil must be unjust; and 4. The evil must be the determining cause for the party upon whom it is employed in entering into the contract Intimidation and Reluctant Consent, Distinguished Consent given in intimidation must be distinguished from a consent given reluctantly. In case of a consent given reluctantly, it is still clear that one acts as voluntarily and independently in the eyes of the law when he acts as reluctantly and with hesitation as when he acts spontaneously and joyously. Hence, he acts voluntarily and freely when he acts wholly against his better sense and judgment as when he acts in conformity with them. Determination of Degree of Intimidation – To determine the degree of intimidation, the age, sex and condition of the person intimidated shall be borne in mind. “condition” refers not only to the resolute or weak character of the person intimidated, but also to his other circumstances, such as his capacity or culture, financial condition, etc. Effect of Just or Legal Threat – A threat to enforce one’s claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. Illustration: D borrowed P 10,000.00 from C. Upon maturity of the debt, D failed to pay. C told D that if the latter still fails to pay, an action will be brought in court against him. The threat in this case is valid as it only means enforcement of the collection of the obligation. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1337. There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. The following circumstances shall be considered: the confidential, family, spiritual and other relations between the parties, or the fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weaknesses, or was ignorant or in financial distress. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Undue Influence Undue Influence – there is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice; the influence which deprives a person of his free agency. 89 Undue Influence which Vitiates Consent The test in order to determine whether there is undue influence which will invalidate a contract is to determine whether the influence exerted has so overpowered or subjugated the mind of a contracting party as to destroy his free agency, making him express the will of another rather than his own. Even if it can be established that a person entered into a contract through the importunity or persuasion of another against his better judgment, if the deprivation of his free agency is not proved, there is no undue influence which will vitiate consent. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1338. There is fraud when, through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other has induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed to. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Fraud Fraud – those insidious words or machinations employed by one of the contracting parties in order to induce the other to enter into a contract, which, without them, he would not have agreed to. Kinds of Fraud – fraud under Article 1338 must not be confused with the fraud which is mentioned under Articles 1170 and 1171. 1. Fraud in the perfection of the contract (Art. 1338) – the fraud which is employed by a party to the contract in securing the consent of the other party. a. Dolo Causante (causal fraud) – refers to those deceptions or misrepresentations of a serious character employed by one party and without which the other party would not have entered into the contract. This is the fraud which is defined in Article 1338. b. Dolo Incidente (incidental fraud) – refers to those deceptions or misrepresentations which are not serious in character and without which the other party would still have entered into the contract. This is the fraud referred to in Article 1344. 2. Fraud in the performance of the obligation (Art. 1170) – fraud which is employed by the obligor in the performance of a pre-existing obligation. Dolo Causante and Dolo Incidente, Distinguised Dolo Causante Dolo Incidente As to Character MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Serious in character Not serious in character As to Purpose Induces the party upon Not the cause which whom it is employed in induces the other party into entering into the contract entering into the contract As to Effect The effect is to render the The effect is to render the contract voidable party who employed it liable for damages Requisites (OSIB) 1. Fraud or insidious machinations must have been employed by one of the contracting parties; 2. The fraud or insidious words or machinations must have been serious; 3. The fraud or insidious words or machinations must have induced the other party to enter into the contract; and 4. The fraud should not have been employed by both of the contracting parties or by a third person. Nature of Fraud – The essence of the fraud under the article lies in the deception or misrepresentation employed by one of the contracting parties to secure the consent of the other. It is also essential that such insidious words or machinations must be prior to or contemporaneous with the birth or perfection of the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1339. Failure to disclose facts, when there is a duty to reveal them, as when the parties are bound by confidential relations, constitutes fraud. Art. 1340. The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. Art. 1341. A mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former’s special knowledge. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Effects of Failure to Disclose Facts Failure to disclose facts, when there is a duty to reveal them, as when the parties are bound by confidential relations, constitutes fraud. However, the innocent nondisclosure of a fact, when there is no duty to reveal it, does not constitute fraud. Illustration: A applied for life insurance coverage with Insurance Co. In the questionnaire, there is a question 90 as to whether the applicant has diabetes. A knows that he has diabetes. Nevertheless, he answered “no” to the question. In this case, the failure of A to disclose the fact that he has diabetes constitutes fraud. Illustration: A applied for life insurance coverage with Insurance Co. In the questionnaire, there is a question as to whether the applicant drinks alcoholic drinks. A knows that he occasionally drink alcohol. Nevertheless, he answered “no” to the question. The non-disclosure in this case is not fraudulent as the answer has not the intent to defraud. The reason is that the reality that he is an occasional drinker will not change the decision of the insurance company to accept the applicant under its coverage. Effect of Exaggerations in Trade The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. Illustration: Pizza Co. offered what according to its advertisements is “the most delicious pizza in the world”. A, a lover of pizza, immediately went to a branch of Pizza Co. and ordered “the most delicious pizza in the world”. However, he was disappointed as the pizza is not delicious. The advertisement is not a false representation as A had in fact an opportunity to know that the pizza was not really the most delicious pizza in the world. It is really an exaggeration which is usual in trade. Illustration: One day, A realized that he wants to eat pork and beans. He immediately went to the nearest supermarket and bought 12 cans of Mang Tomas’s Pork and Beans. Upon opening his first can, he noticed that there is no pork in the Pork and Beans. In this case there is no false representation. A had an opportunity to know the facts by reading all the labels printed on the cover of the can. Problem: Relying on the statements that “Panday 2” is “pang-hollywood”, “pang-blockbuster”, “sobrang ganda ng visual effects”, “ang ganda ng story”, and “no. 1 movie this year”, A went to the nearest cinema to watch Pandy 2. However, watching the movie cause only disappointment. The visual effects of the movie was indeed “pang-hollywood” some 20 to 30 years ago; the movie was indeed “pang-hollywood” as MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER it was only an attempt to pirate the ideas of Hollywood movies such as “Clash of the Titans” and “How to train your dragon.” Can A sue GMA and Imus Productions (the producers of the movie) for false representations? Answer: No, A cannot sue them on the ground that Panday 2 is the suckiest movie ever and therefore far from the representation made that it is “panghollywood”. A had an opportunity to know that the statements were only to promote the movie and therefore tends to be exaggerated. Effect of Expression of Opinion A mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former’s special knowledge. Illustration: F, a farmer, found a shiny yellowish metal which he thought to be gold. Relying on F’s belief that the stone is gold, P bought the same from F. However, it turned out that the metal is not gold but just an ordinary metal that happens to be shiny. In this case, P cannot avoid the contract of sale on the ground of fraud. Under Article 1341, a mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former’s special knowledge. F is clearly not an expert. Nevertheless, P can ask that the contract be avoided on the ground of mistake. The sale in this case is voidable because the consent of P was vitiated by mistake. Under Article 1331, in order that mistake may invalidate consent, it should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract. In this case, P and F honestly believed that the metal was gold. It turned however that it was not. Hence, there is clearly mistake as to the substance of the thing sold. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1342. Misrepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent, unless such misrepresentation has created substantial mistake and the same is mutual. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Effect of Misrepresentation by Third Persons Misrepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent, unless such misrepresentation has created substantial mistake and the same is mutual 91 Even without Article 1342, the rule would still be applicable since it is a logical corollary to the principle that in order to vitiate consent, the fraud must be employed only by one of the contracting parties. The principle would not be applicable if the third person makes the misrepresentation with the complicity or at least, with the knowledge, but without any objection, of the contracting party who is favored. Hence, misrepresentation in this case vitiates consent. Illustration: S offered to B his laptop for P 50,000.00. B signified his interest to buy the car but made reservation about the high price considering that the laptop is “second-hand.” However, X, a third person present at the time of the negotiations, assured B that the laptop is as good as new considering that it has been used for only a month. S knew that the laptop is already one year old and actually experiencing some problem. However, he did not object to the representation made by X. In this case, despite the fact that the false representation was made by a third person, the consent is vitiated. The misrepresentation was with the knowledge of S but he did not object. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1343. Misrepresentation made in good faith is not fraudulent but may constitute error. Art. 1344. In order that fraud may make a contract voidable, it should be serious and should not have been employed by both contracting parties. Incidental fraud only obliges the person employing it to pay damages. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Magnitude of Fraud The serious character of fraud refers not to its influence, but to its importance or magnitude. Hence, the annulment of the contract cannot be invoked just because of the presence of a minor, or common acts of fraud whose veracity could easily have been investigated. The annulment cannot also be invoked because of the presence of ordinary deviations from the truth, deviations, which are almost inseparable from ordinary commercial transactions, particularly those taking place in fairs or markets. Relation between Fraud and Consent – To vitiate consent, the fraud must be the principal or causal MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER inducement or consideration for the consent of the party who is deceived in the sense that he would never have given consent were it not for the fraud. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1345. Simulation of a contract may be absolute or relative. The former takes place when the parties do not intend to be bound at all; the latter, when the parties conceal their true agreement. Art. 1346. An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void. A relative simulation, when it does not prejudice a third person and is not intended for any purpose contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy binds the parties to their real agreement. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Simulation of Contracts Simulation of contracts may either be absolute or relative. a. Absolute – when there is colorable contract but it has no substance as the contracting parties do not intend to be bound by the contract at all, as when a debtor simulates the sale of his properties to a friend in order to prevent their possible attachment by creditors. b. Relative – when the contracting parties state a false cause in the contract to conceal their true agreement, as when a person conceals a donation by simulating a sale of the property to the beneficiary for a fictitious consideration. Effects Simulation of contracts affects the contract in an entirely different manner. An absolutely simulated contract is void, while a relatively simulated contract binds the parties and the parties may recover from each other what they may have given under the contract, while a relatively simulated contract is binding and enforceable between the parties and their successors in interest to their real agreement, when it does not prejudice a third person and is not intended for any purpose contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. Contracts of Adhesion Contract of Adhesion – a type of contract where the terms are prepared by only one of the parties while the other party merely affixes his signature signifying his adhesion thereto. A contract of adhesion is just as binding as ordinary contracts. Hence, they are not invalid per se. The one who adheres to the contract is in reality free to reject it entirely. If he adheres, he gives his consent. 92 However, when the terms of the contract are ambiguous, the terms thereof shall be construed liberally in favor of the party who merely affix his signature, and strictly against the party who cause the ambiguity which is of course the party who prepared the terms of the contract. Object of Contract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1347. All things which are not outside the commerce of men, including future things, may be the object of a contract. All rights which are not intransmissible may also be the object of contracts. No contract may be entered into upon future inheritance except authorized by law. All services which are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy may likewise be the object of a contract. Art. 1348. Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. Art. 1349. The object of every contract must be determinate as to its kind. The fact that the quantity is not determinate shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract, provided it is possible to determine the same, without the need of a new contract between the parties. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------What may be the Object of Contracts As a general rule, all things or services may be the object of contracts. Requisites (LCD-R) 1. The object should be within the commerce of men; in other words, it should be susceptible of appropriation and transmissible from one person to another; 2. The object should be real or possible; in other words, it should exist at the moment of the celebration of the contract, or at least, it can exist subsequently or in the future; 3. The object should be licit; 4. The object should be determinate, or at least, possible of determination, as to its kind. Example of Things which cannot be the Object of Contracts MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 1. Things which are outside the commerce of men; 2. Intransmissible rights; 3. Future inheritance, except in cases expressly authorized by law; 4. Services which are contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy; 5. Impossible things or services; and 6. Objects which are not possible of determination as to their kind. Illustration: S sold to B all the air which is passing on its property. The object in this case is invalid as they are outside the commerce of men. To be within the commerce of man, the thing must be susceptible of appropriation. The air is a res communes (those belonging to everyone). Res communes cannot be appropriated. Illustration: B offered to buy from S a phoenix or a mermaid in consideration of P 10,000,000.00. The object(s) in this case are invalid. They are not real. Illustration: S sold to B 20 kilograms of marijuana. In this case the object of the contract is unlawful. Since the object is not licit, the contract is not valid. Illustration: S sold to B an animal. The object in this case is invalid not being determinate, or at least determinable. However, it would have been different if what was offered was a pair of love birds, or a Chihuahua, or a Persian cat. In such case the object is determinate or determinable and hence valid. Appropriability and Transmissibility In order that a thing, right or service may be the object of a contract, it is essential that it must be within the commerce of men. Consequently, two conditions must concur: 1. The thing, right, or service should be susceptible of appropriation; and 2. It should be transmissible from one person to another Things, rights, or services which do not possess these conditions or characteristics are outside the commerce of men, and therefore, cannot be the object of contracts. These include: i. Those things which are of their very nature, such as common things like the air or sea, sacred things, res nullius, and property belonging to the public domain; ii. Those which are made such by special prohibitions established by law, such as 93 iii. poisonous substances, drugs, arms, explosives, and contrabands; and Those rights which are intransmissible because either they are purely personal in character Things which have Perished – Things which have perished cannot be the object of contracts because they are inexistent. Future Things – Future things may be the object of contracts. Future Things – those which do not belong to the obligor at the time the contract is made; they may be made, raised, or acquired by the obligor after the perfection of the contract. It includes not only material objects but also future rights. When the contract involves future things, it may either be: 1. Conditional, or subject to the coming into existence of the thing; or 2. Aleatory, or one of the parties bears the risk of the thing never coming into existence. Rule with Respect to Future Inheritance Generally, future things may the object of contracts. The exception to this rule is future inheritance. Inheritance includes all the property, rights, and obligations of a person which are not extinguished by his death. The reason for the rule is because if the rule were otherwise, there would always be a possibility that one of the contracting parties may be tempted to instigate the death of the other in order that inheritance will become his. Requisites for the Prohibition: 1. The succession has not yet been opened; 2. The object of the contract forms part of the inheritance; and 3. That the promissor has, with respect to the object, an expectancy of a right which is purely hereditary in nature. Impossible Things or Services – Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. Things are impossible when they are susceptible of existing or they are outside the commerce of man. Personal services or acts are impossible when they are beyond the ordinary strength or power of man. The impossibility must be actual and contemporaneous with the making of the contract, and not subsequent thereto. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Therefore, a distinction must be made between absolute impossibility and relative impossibility. Absolute impossibility renders the contract void as it arises from the very nature or essence of the act or service itself. Relative impossibility allows the perfection of the contract although fulfilment thereof is hardly probable as it arises from the circumstances or qualifications of the obligor rendering him incapable of executing the act or service. Determinability of Object That the thing must be determinate as to its kind simply means that the genus of the object should be expressed although there might be no determination of the individual specie. A thing is determinate when it is particularly designated or physically segregated from all other of the same class (Art. 1460, par. 1) A thing is determinable if at the time the contract is entered into, the thing is capable of being made determinate without the necessity of a new or further agreement between the parties (Art. 1460, par. 2) There need not be any specification as to the qualities and circumstances of the thing which constitutes the object of the contract. Illustration: S offered to B his car for P 500,000.00. The object in this case is determinate as the object is particularly designate (i.e., S’s car). If S owns many cars then it is determinable as the thing is capable of being made determinate without the need to enter into a new agreement. Illustration: B bought 10 tons of wagwag rice from B for P 500,000.00. In this case, the object is determinable because at the time the contract is entered into, the thing is capable of being made determinate without necessity of a new or further agreement between the parties. Nevertheless, the thing here will be determinate at the time of delivery because at such time, the 10 tons of wagwag rice has already been physically segregated from all others of the same class. Cause of Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------94 Art. 1350. In onerous contracts the cause is understood to be, for each of the contracting party, the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other; in remuneratory ones, the service or benefit remunerated; and in contracts of pure beneficence, the mere liberality of the benefactor. Art. 1351. The particular motives of the parties in entering into a contract are different from the cause thereof. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Cause of Contracts Cause of the Contract – it is the immediate, direct or most proximate reason which explains and justifies the creation of an obligation through the will of the contracting parties. It is the “why” of the contract or the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into the contract. Distinguished from Consideration In this jurisdiction, cause and consideration are used interchangeably. However, in civil law jurisdictions, causa or cause is broader in scope than consideration in AngloAmerican jurisdictions. Distinguished from Object In remuneratory contracts, the cause is the service or benefit which is remunerated, while the object is the thing which is given in remuneration. Remuneratory contract is one in which one of the contracting parties remunerates (rewards, compensates, reimburses) the service or benefit rendered or given by the other party, although such service or benefit does not constitute a demandable debt. Illustration: A is an employee of X. Due to the efforts of A, the company of X gained a lot of profits. In consideration of the efforts by A, X gave him a brand new car. In this case the cause or consideration is the efforts of A or the huge profit acquired by the company of X, while the object is the car. In gratuitous contracts, the cause is the liberality of the donor or the benefactor, while the object is the thing which is given or donated Illustration: A donated a parcel of land to the Global Church. In this cause, the cause or consideration is the mere liberality of A while the object is the parcel of land. In onerous contracts, the cause is the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other, while the object is the thing or service itself MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Illustration: S sold to B his car for P 500,000.00. In this case, the cause or consideration is, as regards S, the seller, the promise of B to deliver the purchase price of P 500,000.00, whereas as regards B the cause or consideration is the promise of S to deliver the car. The object of the contract is the car. The cause of the accessory contract is identical with that of the principal contract In moral obligations, where the moral obligation arises wholly from ethical considerations, unconnected with any civil obligation and, as such, is not demandable in law but only in conscience, it cannot constitute a sufficient cause or consideration to support an onerous contract. But where such moral obligation is based upon a previous civil obligation which has already been barred by the statute of limitations at the time when the contract is entered into, it constitutes a sufficient cause or consideration to support the said contract. Distinguished from Motives Cause is not equivalent to motive. The cause in a particular kind of a contract is always the same whereas motive, are as different or complex and as capable of infinite variety as the individual circumstances which may move men to acquire things or make money. However, when the motive of the contracting parties predetermines the purpose of the contract and such motive or purpose is illegal or immoral, it is clear that such illegal motive or purpose becomes the illegal causa, thus rendering the contract void ab initio. Cause Motive The direct or most The indirect or remote proximate reason of a reasons contract The objective or juridical The psychological or purely reason of a contract personal reasons Cause is always the same Differ for each contracting party ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1352. Contracts without cause, or with unlawful cause, produce no effect whatsoever. The cause is unlawful if it is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. Art. 1353. The statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void, if it should not be proved that 95 they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. Art. 1354. Although the cause is not stated in the contract, it is presumed that it exists and is lawful, unless the debtor proves the contrary. Art. 1355. Except in cases specified by law, lesion or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract, unless there has been fraud, mistake, or undue influence. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Essential Requisites of Cause 1. The cause should be in existence at the time of the celebration of the contract; 2. The cause should be licit or lawful; and 3. The cause should be true. If the cause of the contract is false, it shall produce no effect, unless it can be proved that the contract is, in reality, founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. Effect of Lack of Cause If the contract is not founded upon any cause, then it shall not produce any effect whatsoever. The rule is not applicable where the purchaser or vendee failed to fully pay for the property, even if there is a stipulation in the contract of sale that full payment shall be made at the time of the celebration thereof. If the contract provides for a substantially small consideration like P 1.00 for a parcel of land, the same is not void or inexistent. In this case, there is still consideration. The contract is also not voidable but the inadequacy of the consideration may be an evidence of the presence of fraud, mistake, or undue influence which would render the contract voidable. Illustration: S sold to B his car for P 500,000.00. S delivered the car to B but payment of the purchase price will be made only after a month. In this case even if B failed to pay the purchase price, the same would not render the contract void. There is actually a consideration in this case: the promise by the buyer to give the purchase price, from the view point of the seller, and the promise to deliver the car from the point of view of the buyer. Moreover, in this case ownership is already transferred to the buyer by virtue of the delivery. Illustration: B purchased a 1 hectare parcel of land from S for P 1.00. In this case, the contract is valid MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER and not void or voidable. It may even be argued that the price is equivalent in value to the thing purchased so long as the party believes that he is receiving good value for what he transferred. However, inadequacy of price, while not a sufficient ground for the cancellation of a voluntary contract, it may nevertheless show vice in consent and hence can be an evidenced which will show that the contract is voidable (but again, the mere fact that the consideration is inadequate is not sufficient to make the contract voidable, much less void) Effect of Unlawful Cause The cause is unlawful if it contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. If the cause is unlawful, the contract shall not produce any effect whasoever. Illustration: A promised to give B P 500,000.00 if B would kill X. The cause in this case is unlawful. Hence, the contract is void. Effect of False Cause The statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void unless it should be proved that they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. Illustration: S and B executed a contract of sale where it was stated that B acquired from S a parcel of land in consideration of P 50,000.00. However, it was found out that B never paid a single cent for the property and the ownership of the same property has not been transferred to B. It was also proved that S continued to be the actual owner of the property. In this case the sale is fictitious. If the parties would not be able to prove that the contract is founded upon another consideration which is valid, then the contract is an absolutely fictitious contract which is void. However, if the parties can show that there is another consideration which is valid then the contract is relatively simulated and the parties are bound to their true agreement. Hence, in the same example, if the true consideration is a car which B transferred to S in exchange for the land, then the parties are bound to the contract of barter. Forms of Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1356. Contracts shall be obligatory, in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the 96 essential requisites for their validity are present. However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. In such cases, the right of the parties stated in the following article cannot be exercised. Art. 1357. If the law requires a document or other special form, as in the acts and contracts enumerated in the following article, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. Art. 1358. The following must appear in a public document: 1. Acts and contracts which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable property; sales of real property or of an interest therein are governed by articles 1403, No. 2, and 1405; 2. The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains; 3. The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person; 4. The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document. All other contracts where the amount involved exceeds five hundred pesos must appear in writing, even a private one. But sales of goods, chattels or things in action are governed by articles, 1403, No. 2 and 1405. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Form of Contract General rule: contracts shall be obligatory whatever may be the form they may have been entered into provided all the essential requisites for its validity are present. Exceptions: 1. When the law requires that the contract must be in a certain form in order to be valid; and 2. When the law requires that the contract must be in a certain form in order to be enforceable Forms Required by Law 1. Formalities for Validity MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 2. Formalities for Enforceability 3. Formalities for Efficacy Formalities for Validity There are certain contracts for which the law prescribes certain forms for their validity. These contracts may be classified as follows: 1. Those which must appear in writing a. Donations of personal property whose value exceeds five thousand pesos (P 5,000.00) (Art. 748) b. Sale of a piece of land or any interest therein through an agent (Art. 1874) c. Agreements regarding payment of interest in contracts of loan. (Art. 1956) d. Antichresis. In a contract of antichresis, the amount of the principal and of the interest shall be specified in writing otherwise the contract shall be void. (Art. 2134) 2. Those which must appear in a public document a. Donations of immovable property (Art. 749) b. Partnerships where immovable property or real rights are contributed to the common fund (Arts. 1771 and 1773) 3. Those which must be registered a. Chattel mortgages (Art. 2140) b. Sales or transfers of large cattles (Cattle Registration Act) Formalities for Enforceability There are contracts which are unenforceable by action, unless they are in writing and properly subscribed, or unless they are evidenced by some note or memorandum, which must also be in writing and properly subscribed. These contracts are governed by the Statute of Frauds (Art. 1403) Formalities for Efficacy Aside from formalities for validity and enforceability, the law also prescribes a certain form in the execution of some contracts. The purpose of the requirement, however, is not to validate or to enforce the contract, but merely to insure its efficacy. Hence, contracts which failed to comply with the requirements for efficacy are still obligatory. Principles Applicable to Formalities for Efficacy 1. Articles 1357 and 1358 do not require the execution of the contract either in a public or private document in order to validate or enforce it but only to ensure its 97 efficacy, so that after its existence has been admitted, the party bound may be compelled to execute the necessary document. 2. Even where the contract has not been reduced to the required form, it is still valid and binding as far as the contracting parties are concerned. Consequently, Articles 1357 and 1358 presupposes the existence of a contract which is valid and binding. 3. From the moment one of the contracting parties invokes the provisions of Articles 1357 and 1358 by means of a proper action, the effect is to place the existence of the contract in issue, which must be resolved by the ordinary rules of evidence. 4. Article 1357 does not require that the action to compel the execution of the necessary document must precede the action upon the contract. Both actions may be exercised simultaneously. 5. However, although the provisions of Article 1357, in connection with Article 1358, do not operate against the validity of the contract nor for the validity of the acts voluntarily performed by the parties for the fulfilment thereof, yet from the moment when any of the contracting parties invokes said provisions, it is evident that under them the execution of the required document must precede the determination of the other obligations derived from the contract. Reformation of Instruments ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1359. When, there having been a meeting of the minds of the parties to a contract, their true intention is not expressed in the instrument purporting to embody the agreement, by reason of mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct or accident, one of the parties may ask for the reformation of the instrument to the end that such true intention may be expressed. If mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident has prevented a meeting of the minds of the parties, the proper remedy is not reformation of the instrument but annulment of the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Doctrine of Reformation of Instruments When the true intention of the parties to a perfected and valid contract are not expressed in the instrument purporting to embody their agreement by reason of mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident, one of the MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER parties may ask for the reformation of the instrument so that such true intention may be expressed. The doctrine is based on justice and equity. Upon the reformation of the instrument, the general rule is that it relates back to and takes effect from the time of its original execution, especially as between the parties. Requisites 1. There must be a meeting of the minds of the contracting parties. In other words, there must be a perfected contract; 2. Their true intention is not expressed in the instrument; and 3. Such failure to express their true intention is due to mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct or accident. Distinguished from Annulment of Contracts Reformation of Contracts Annulment of Contracts Presupposes a valid and Based on a defective perfected contract contract in which there has been no meeting of the minds because the consent of one or more of the contracting parties has been vitiated Reformation gives life to the Annulment involves a contract upon certain complete nullification of the corrections. contract. Hence, if mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident has prevented a meeting of the minds of the parties, the proper remedy is not reformation of the instrument but annulment of the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1360. The principles of the general law on the reformation of instruments are hereby adopted insofar as they are not in conflict with the provisions of this Code. Art. 1361. When a mutual mistake of the parties causes the failure of the instrument to disclose their real agreement, said instrument may be reformed. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Requisites of Mistake To justify reformation under Article 1361, it must be shown conclusively that: 1. The mistake is one of fact, as when the written evidence of the agreement includes something which should not be there or omits something which should be there; 98 2. It was common to both parties; and 3. Proof of mistake must be clear and convincing which is more than a mere preponderance of evidence. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1362. If one party was mistaken and the other acted fraudulently or inequitably in such a way that the instrument does not show their true intention, the former may ask for the reformation of the instrument. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Mistake by One Party A written instrument may be reformed where there is mistake on one side and fraud or inequitable conduct on the other as where one party to an instrument has made a mistake and the other knows it and conceals the truth from him. Mistake of one party, under this article, must refer to the contents of the instrument and not the subject matter or principal conditions of the agreement; in the latter case, an action for annulment of the contract is the proper remedy. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1363. When one party was mistaken and the other knew or believed that the instrument did not state their real agreement, but concealed that fact from the former, the instrument may be reformed. Art. 1364. When through the ignorance, lack of skill, negligence or bad faith on the part of the person drafting the instrument or of the clerk or typist, the instrument does not express the true intention of the parties, the courts may order that the instrument be reformed. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Mistake of Draftsman Whenever an instrument is drawn with the intention of carrying an agreement previously made, but which, due to mistake or inadvertence of the draftsman or clerk, does not carry out the intention of the parties, but violates it, there is ground to correct the mistake by reforming the instrument. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1365. If two parties agree upon the mortgage or pledge of real or personal property, but the instrument states that the property is sold absolutely or with a right of repurchase, reformation of the instrument is proper. Art. 1366. There shall be no reformation in the following cases: 1. Simple donations inter vivos wherein no condition is imposed; 2. Wills; 3. When the real agreement is void. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Art. 1367. When one of the parties has brought an action to enforce the instrument, he cannot subsequently ask for its reformation. Art. 1368. Reformation may be ordered at the instance of either party or his successors in interest, if the mistake was mutual; otherwise, upon petition of the injured party, or his heirs and assigns. Art. 1369. The procedure for the reformation of instrument shall be governed by rules of court to be promulgated by the Supreme Court. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contracts of Adhesion Contract of Adhesion – one in which one of the parties imposes a ready-made form of contract, which the other party may accept or reject, but which the latter cannot modify. Interpretation of Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1370. If the terms of a contract are clear and leave no doubt upon the intention of the contracting parties, the literal meaning of its stipulations shall control. If the words appear to be contrary to the evident intention of the parties, the latter shall prevail over the former. Art. 1371. In order to judge the intention of the contracting parties, their contemporaneous and subsequent acts shall be principally considered. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Primacy of Intention of the Parties The cardinal rule in the interpretation of contracts is to the effect that the intention of the contracting parties should always prevail because their will has the force of law between them. If the terms of the contract are clear and leave no doubt as to the intention of the contracting parties, the literal sense of its stipulations shall be followed. If the words appear to be contrary to the evident intention of the contracting parties, the intention shall prevail. The evident intention which prevails against the defective wording of the contract is not that of one of the parties but the general intent, which, being so, is to a certain extent equivalent to mutual consent, inasmuch as it was the result desired and intended by the contracting parties. 99 How to Judge Intention – In order to judge the intention of the parties, their contemporaneous and subsequent acts shall be principally considered. This is without prejudice to the consideration of other factors as fixed or determined by the other rules of interpretation mentioned in the Civil Code and in the Rules of Court. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1372. However general the terms of a contract may be, they shall not be understood to comprehend things that are distinct and cases that are different from those upon which the parties intended to agree. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Scope of General Terms When a general and a particular provision are inconsistent, the latter is paramount to the former. So a particular intent will control a general one that is inconsistent with it. The contract cannot also be constructed so as to include matters distinct from those with respect to which the parties intended to contract. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1373. If some stipulation of any contract should admit of several meanings, it shall be understood as bearing that import which is most adequate to render it effectual. Art. 1374. The various stipulations of a contract shall be interpreted together, attributing to the doubtful ones that sense which may result from all of them taken jointly. Art. 1375. Words which may have different significations shall be understood in that which is most in keeping with the nature and object of the contract. Art. 1376. The usage or custom of the place shall be borne in mind in the interpretation of the ambiguities of a contract, and shall fill the omission of stipulations which are ordinarily established. Art. 1377. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity. Art. 1378. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity. If the doubts are cast upon the principal object of the contract in such a way that it cannot be known what may have been the intention or will of the parties, the contract shall be null and void. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Art. 1379. The principles of interpretation stated in Rule 123 of the Rules of Court shall likewise be observed in the construction of contracts. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Defective Contracts Classes of Defective Contracts – there are four classes of defective contracts. They are: a. Rescissible b. Voidable c. Unenforceable d. Void or inexistent Essential Features of Defective Contracts 1. As to Defect a. Rescissible contracts – there is damage or injury either to one of the contracting parties or to third persons; b. Voidable contracts – there is vitiation of consent or legal incapacity of one of the contracting parties c. Unenforceable contracts – the contract is entered into in excess or without any authority, or does not comply with the Statute of Frauds, or both contracting parties are legally incapacitated d. Void or inexistent contracts – one or some of the essential requisites of a valid contract are lacking either in fact or in law. 2. As to Effect a. Rescissible contracts – considered valid and enforceable until they are rescinded by a competent court; b. Voidable contracts – considered valid and enforceable until they are annulled by a competent court; c. Unenforceable contracts – cannot be enforced by a proper action in court; d. Void or inexistent contracts – as a general rule, produce any legal effect 3. As to Prescriptibility of Action or Defense a. Rescissible contracts – the action for rescission may prescribe; b. Voidable contracts – the action for annulment or the defense of annullability may prescribe; c. Unenforceable contracts – the corresponding action for recovery, if there was total or partial performance of the unenforceable contract under no. 1 or no. 3 of Art. 1403, may prescribe; 100 d. Void or inexistent contracts – the action for declaration of nullity or inexistence or the defense of nullity or inexistence does not prescribe 4. As to Susceptibility of Ratification a. Rescissible contracts – not susceptible of ratification; b. Voidable contracts – susceptible of ratification; c. Unenforceable contracts – susceptible of ratification; d. Void or inexistent contracts – not susceptible of ratification 5. As to who may Assail Contracts a. Rescissible contracts – may be assailed not only by a contracting party but even by a third person who is prejudiced or damaged by the contract; b. Voidable contracts – may be assailed only by a contracting party; c. Unenforceable contracts – may be assailed only by a contracting party; d. Void or inexistent contracts – may be assailed not only by a contracting party but even by a third person whose interest is directly affected 6. As to how may be Assailed a. Rescissible contracts – may be assailed directly only, and not collaterally; b. Voidable contracts – may be assailed directly or collaterally; c. Unenforceable contracts – may be assailed directly or collaterally; d. Void or inexistent contracts – may be assailed directly or collaterally. Rescissible Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1380. Contracts validly agreed upon may be rescinded in the cases established by law. Art. 1381. The following contracts are rescissible. 1. Those which are entered into by guardians whenever the ward whom they represent suffer lesion by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object thereof; 2. Those agreed upon in representation of absentees if the latter suffer the lesion stated in the preceding number; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 3. Those undertaken in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any manner collect the claims due them; 4. Those which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority; 5. All other contracts specially declared by law to be subject to rescission. Art. 1382. Payments made in a state of insolvency for obligations to whose fulfilment the debtor could not be compelled at the time they were effected, are also rescissible. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rescissible Contracts Rescissible contract is a contract which is valid because it contains all of the essential requisites prescribed by law, but which is defective because of injury or damage to either of the contracting parties or to third persons, such as creditors, as a consequence of which it may be rescinded by means of a proper action for rescission. The only way by which a rescissible contract may be attacked is by means of a direct action for rescission based on any of the causes expressly specified by law. It cannot be attacked collaterally. Characteristics of Rescissible Contracts 1. Their defect consists in injury or damage either to one of the contracting parties or to third persons; 2. Before rescission, they are valid, and therefore, legally effective; 3. They can only be attacked directly, not collaterally; 4. They can be attacked only either by a contracting party or by a third person who is injured or defrauded; 5. They are susceptible of convalidation only by prescription and not by ratification Rescission Rescission – a remedy granted by law to the contracting parties, and even to third persons, to secure the reparation of damages caused to them by a contract, even if the same should be valid, by means of the restoration of things to their condition prior to the celebration of the contract. Rescission and Resolution, Distinguished Rescission (Art. 1380) Resolution (1191) As to Party who may Institute the Action May be instituted not only May be instituted only by a by a party to the contract party to the contract (the 101 but also by a third person, injured party) provided they suffered injury by reason of the contract sought to be rescinded As to Causes There several causes or The only ground is failure of grounds for rescission, such one of the contracting as rescission, fraud, and parties to comply with what others expressly specified is incumbent upon him by law As to Power of the Courts The courts has no power to The law expressly declares grant an extension for the that courts shall have a performance of the discretionary power to grant obligation so long as there extension for performance is a ground for rescission provided that there is just cause As to Contracts which may be Rescinded or Resolved Any contract, whether Only reciprocal contracts unilateral or reciprocal, may may be resolved be rescinded As to Character Rescission as an action is Primary. subsidiary. Rescission and Mutual Consent, Distinguished Rescission Mutual Consent As to Causes The causes are those which Cause is not based on the are expressly specified by grounds for rescission but law as ground for rescission depends upon the parites such as lesion, fraud and any other cause specified by law As to Laws Applicable The laws applicable are The law applicable is the Articles 1380 to 1389 stipulation of the parties. A contracts is the law as between the contracting parties and should be complied with in good faith As to Effects The effect is mutual Effects shall be governed by restitution when the ground the agreement of the parties for rescission is lesion. as mutual consent is, in reality, just another contract which object is to dissolved MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER a previous one Contracts which may be Rescinded 1. Contracts in Behalf of Ward Contracts entered into by guardians in behalf of the ward, whenever the ward whom they represent suffer lesion or damage by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object of the contract, are rescissible. However, rescission shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts even if the ward shall suffer the lesion stated in the article. The contracts referred to under this ground are contracts involving acts of administration and not for acts of ownership. Acts of administration does not require court approval for its validity. However, as already stated, if such act was approved by the court but the ward suffered lesion as stated in the article, no rescission shall take place. If the contract involves acts of ownership, and hence, beyond the guardian’s powers to perform, and no judicial approval was procured, the contract is unenforceable and not rescissible. 2. Contracts in Behalf of Absentees Contracts entered into by legal representatives in behalf of the absentee, whenever the absentee whom they represent suffer lesion or damage by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object of the contract, are rescissible However, rescission shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts even if the ward shall suffer the lesion stated in the article The contracts referred to under this ground are contracts involving acts of administration and not for acts of ownership If the contract involves acts of ownership, and hence, beyond the guardian’s powers to perform, and no judicial approval was procured, the contract is unenforceable and not rescissible Requisites of Rescission on the Ground of Lesion 1. The contract must have been entered into by a guardian in behalf of the ward or by a legal representative in behalf of an absentee; 102 2. The ward or absentee must have suffered lesion of more than one-fourth of the value of the property which is the object of the contract; 3. The contract must have been entered into without judicial approval; 4. There must be no other legal means for obtaining reparation for lesion; 5. The person bringing the action must be able to return whatever he may be obliged to restore; and 6. The object of the contract must not be legally in the possession of a third person who did not act on bad faith 3. Contracts in Fraud of Creditors Contracts entered into in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any other manner collect the claims them are rescissible. This complements Article 1177. The basis for rescission here is fraud. Requisites of Rescission of Contracts in Fraud of Creditors 1. There must be a credit existing prior to the celebration of the contract; 2. There must be a fraud, or at least, the intent to commit fraud to the prejudice of the creditor seeking the rescission; 3. The creditor cannot in any other legal manner collect his credit; and 4. The object of the contract must not be legally in the possession of a third person who did not act in bad faith. Accion Pauliana – the action to rescind contracts in fraud of creditors. For the action to prosper, the following requisites must concur. 1. The plaintiff asking for rescission has a credit prior to the alienation, the date of the judgment enforcing it is immaterial; 2. The debtor has made subsequent contract conveying a patrimonial benefit to a third person; 3. The creditor has no other legal remedy to satisfy his claim; 4. The act being impugned is fraudulent; and 5. The third person who received the property conveyed, if it is by onerous title, has been an accomplice in the fraud. Note: actually, the requisites under “requisites of rescission of contracts in fraud of creditors” and the requisites here should be the same. Accion pauliana MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER and rescission of contracts in fraud of creditors as an action are the same. 4. Contracts Referring to Things under Litigation Contracts which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority may be rescinded. The basis for rescission here is fraud. The purpose here is to secure the possible effectivity of a claim, while in No. 3 the purpose is to guarantee an existing credit. Here, there is a real right involved, while in No. 3 there is a personal right. 5. Contracts by Insolvent Payments made in a state of insolvency for obligations to whose fulfilment the debtor could not be compelled at the time they were effected are rescissible. The basis for rescission here is fraud. Insolvency, as it is understood in this article, should be understood in its popular or vulgar, not technical, sense. Hence, it refers to the financial situation of the debtor by virtue of which it is impossible for him to fulfil his obligations. A judicial declaration of insolvency is not necessary. Requisites 1. Payment must have been made in a state of insolvency; and 2. The obligation must have been one which the debtor could not be compelled to pay at the time such payment was effected 6. Other Rescissible Contracts Expressly Specified by Law Contracts which can be rescinded as expressly specified by law are: a. Art. 1098 b. Art. 1526 c. Art. 1534 d. Art. 1539 e. Art. 1542 f. Art. 1556 g. Art. 1560 h. Art. 1567 i. Art. 1659 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------103 Art. 1383. The action for rescission is subsidiary; it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rescission, Subsidiary The action for rescission is subsidiary. Hence, it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. It is essential therefore that the party prejudiced has exhausted all of the other legal means to obtain reparation before he can avail himself of the remedy of rescission. Parties who may Institute the Action 1. The person who is prejudiced, such as the party suffering the lesion, the creditor who is defrauded, and other persons authorized to exercise the same in other rescissory actions. 2. Their representatives. 3. Their heirs. 4. Their creditors by virtue of the subrogatory action under Article 1177. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1384. Rescission shall only be to the extent necessary to cover the damage caused. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Extent of Rescission The primary purpose of rescission is reparation for the damage or injury which is suffered by a party to the contract or by a third person. Hence, rescission does not necessarily have to be total in character; it may also be partial. Rescission shall only be to the extent necessary to cover the damages caused. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1385. Rescission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest; consequently, it can be carried out only when he who demands rescission can return whatever he may be obliged to restore. Neither shall rescission take place when the things which are the object of the contract are legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith. In this case, indemnity for damages may be demanded from the person causing the loss. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Effect of Rescission in Case of Lesion Article 1385, paragraph 1 is applicable only to rescissory actions on the ground of lesion and not to rescissory actions on the ground of fraud. In the latter, the plaintiff-creditor has no obligation to restore anything since he has not received anything. Once the contract is rescinded on the ground of lesion, there arises an obligation on the part of both contracting parties to return to the other the object of the contract, including fruits or interests. “fruits of the thing” refer not only to natural, industrial, and civil fruits but also to other accessions obtained by the thing, while interest refers to legal interest. Effect of Rescission upon Third Persons Rescission shall not take place when the thing which constitutes the object of the contract is legally in the possession of a third person who has not acted in bad faith. However, the following requisites must concur: 1. The thing must be legally in the possession of a third person; and 2. Such third person did not act in bad faith. Note: when the thing is immovable, it is indispensable that the right of the third person must be registered in the proper registry before it can be said that it is legally in his possession. When the thing is movable, the principle that possession of movable property acquired in good faith is equivalent to a title applies. If the thing was really in the legal possession of a third person who acted in good faith, the person who is prejudiced may bring an action for indemnity for damages against the person who caused the loss. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1386. Rescission referred to in Nos. 1 and 2 of article 1381 shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts. Art. 1387. All contracts by virtue of which the debtor alienates property by gratuitous title are presumed to have been entered into in fraud of creditors, when the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay all debts contracted before the donation. Alienations by onerous title are also presumed fraudulent when made by persons against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated, and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission. 104 In addition to these presumptions, the design to defraud creditors may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. Art. 1388. Whoever acquires in bad faith the things alienated in fraud of creditors, shall indemnify the latter for damages suffered by them on account of the alienation, whenever, due to any cause, it should be impossible for him to return them. If there are two or more alienations, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Proof of Fraud The existence of fraud or the intent to defraud may be either presumed in accordance with Article 1387 or duly proved in accordance with the ordinary rules of evidence. Presumptions of Fraud The law presumes (disputable presumption) that there is fraud of creditors in the following cases: 1. Alienations of property by gratuitous title if the debtor has not reserved sufficient property to pay all his debts contracted before such alienations; 2. Alienations of property if made by a debtor against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated and need not have been obtained by the party seeking rescission. Badges of Fraud The design to defraud may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. The following circumstances have been denominated by the courts as badges of fraud. 1. The fact that the cause or consideration of the conveyance is inadequate; 2. A transfer made by a debtor after suit has been begun and while it is pending against him; 3. A sale on credit by an insolvent debtor; 4. Evidence of large indebtedness or complete insolvency; 5. The transfer of all or nearly all of his property by a debtor, especially when he is insolvent or greatly embarrassed financially; 6. The fact that the transfer is made between father and son, when there are present others of the above circumstances; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 7. The failure of the vendee to take exclusive possession of all the property. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1389. The action to claim rescission must be commenced within four years. For person under guardianship and for absentees, the period of four years shall not begin until the termination of the former’s incapacity, or until the domicile of the latter is known ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Prescriptive Period Article 1389 does not state the prescriptive period of an action for rescission if the ground is fraud. However, it would seem that the applicable rule is that the prescriptive period is still four years but it will be counted from the time of the discovery of the fraud. Voidable Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1390. The following contracts are voidable or annullable, even though there may have been no damage to the contracting parties: 1. Those where one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract; 2. Those where the consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. These contracts are binding, unless they are annulled by a proper action in court. They are susceptible of ratification. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Voidable Contracts Voidable Contracts – contracts in which all of the essential elements for validity are present, although the element of consent is vitiated either by lack of legal capacity of one of the contracting parties, or by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud. – Voidable contracts are binding until annulled. Characteristics of Voidable Contracts 1. Their defect consists in the vitiation of consent of one of the contracting parties; 2. They are binding until they are annulled by a competent court; 3. They are susceptible of convalidation by ratification or by prescription; 105 4. Their defect or voidable character cannot be invoked by third persons. Voidable and Rescissible Contracts, Distinguished Voidable Contracts Rescissible Contracts As to Character of Defect Defect is intrinsic because it Defect is external because it consists of a vice which consists of damage or vitiates consent prejudice either to one of the contracting parties or to a third person As to Necessity of Damage or Injury Damage or injury to a Damage or injury is contracting party or to a indispensable third person is not necessary. The contract is still voidable even without such damage As to Basis The annullability of the The rescissibility of the contract is based on law. contract is based on equity. Annulment is not only a Rescission is a mere remedy but also a sanction remedy. As to Causes Different from rescission Different from annulment As to Susceptibility to Ratification Susceptible to ratification Not susceptible to ratification As to Persons who may Invoked Annulment may be invoked Rescission may be invoked only by a contracting party by either a contracting party or by a third person who is prejudiced Contracts which are Voidable 1. Those where one of the contracting parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract; 2. Those where consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1391. The action for annulment shall be brought within four years. This period shall begin: In cases of intimidation, violence or undue influence, from the time the defect of the consent ceases. In case of mistake or fraud, from the time of the discovery of the same. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER And when the action refers to contracts entered into by minors or other incapacitated persons, from the time the guardianship ceases. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Prescriptive Period The action for annulment must be commenced within a period of four years. a. If contract refers to one entered into by an incapacitated person, the period shall be counted from the time guardianship ceases; b. If it refers to those where consent is vitiated: By violence, intimidation, or undue influence, the period shall be counted from the time such violence, intimidation, or undue influence ceases or disappears; By mistake or fraud, the period shall be counted from the time of the discovery of such mistake or fraud. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1392. Ratification extinguishes the action to annul a voidable contract. Art. 1393. Ratification may be effected expressly or tacitly. It is understood that there is a tacit ratification if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. Art. 1394. Ratification may be effected by the guardian of the incapacitated person. Art. 1395. Ratification does not require the conformity of the contracting party who has no right to bring the action for annulment. Art. 1396. Ratification cleanses the contract from all its defects from the moment it was constituted. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Ratification Ratification – the act or means by virtue of which efficacy is given to a contract which suffers from a vice of curable nullity. Ratification presupposes the existence of a vice in the contract. Requisites of Ratification 1. The contract should be tainted with a vice which is susceptible of being cured; 2. The confirmation should be effected by the person who is entitled to do so under the law; 106 3. It should be effected with the knowledge of the vice or defect of the contract; 4. The cause of the nullity of defect should have already disappeared Forms of Ratification Ratification requires no specific form. Hence, it may be effected expressly or tacitly (impliedly). Effect of Ratification – Ratification extinguishes the action to annul the contract. Ratification also cleanses the contract of its defects from the moment it was constituted. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1397. The action for the annulment of contracts may be instituted by all who are thereby obliged principally or subsidiarily. However, persons who are capable cannot allege the incapacity of those with whom they contracted; nor can those who exerted intimidation, violence, or undue influence, or employed fraud, or caused mistake base their action upon these flaws of the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Persons who may Institute the Action There are two requisites required to confer the necessary capacity for the exercise of the action for annulment: (1) that the plaintiff must have an interest in the contract; and (2) that the victim and not the party responsible for the vice or defect must be the person who must assert the same. Consequently, a third person who is a stranger to the contract cannot institute an action for its annulment. Exception: a third person not a party obliged principally or subsidiarily under a contract may exercise an action for annulment of the contract if he is prejudiced in his rights with respect to one of the contracting parties,a dn can show detriment which would positively result to him from the contract in which he has no intervention. Also, person capacitated cannot invoke the incapacity of the person with whom they contracted. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1398. An obligation having been annulled, the contracting parties shall restore to each other the things which have been the subject matter of the contract, with their fruits, and the price with its interest, except in cases provided by law. In obligations to render service, the value thereof shall be the basis for damages. Art. 1399. When the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the parties, the incapacitated person MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER is not obliged to make any restitution except insofar as he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Effects of Annulment Annulment of the contract, if the contract has not yet been consummated, releases the parties from the obligations arising from the contract. Obligation of Mutual Restitution Upon the annulment of the contract: a. If the prestation consisted in obligations to give, the parties shall restore to each other the things which have been the subject of the contract, with their fruits, and the price with its interest, except in cases provided by law. b. If the prestation consisted in obligations to do or not to do, there will have to be an apportionment of damages based on the value of such prestation with corresponding interests. Rule in Case of Incapacity The principle of mutual restitution is modified by the rules under Article 1399 which states that when the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the contracting parties, the incapacitated person is not obliged to make any restitution except insofar as he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. Benefit means that there has been a prudent and beneficial use by the incapacitated person of the thing which he has received. In order to determine this, it is necessary to determine his necessities, his social position as well as his duties as a consequence thereof. However, in the absence of proof, it is presumed that no benefit has accrued to the incapacitated person. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1400. Whenever the person obliged by the decree of annulment to return the thing cannot do so because it has been lost through his fault, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. Art. 1401. The action for annulment of contracts shall be extinguished when the thing which is the object thereof is lost through the fraud or fault of the person who has a right to institute the proceedings. If the right of action is based upon the incapacity of any one of the contracting parties, the loss of the thing shall 107 not be an obstacle to the success of the action, unless said loss took place through the fraud or fault of the plaintiff. Art. 1402. As long as one of the contracting parties does not restore what in virtue of the decree of annulment he is bound to return, the other cannot be compelled to comply with what is incumbent upon him. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Effect of Failure to Make Restitution As long as one of the contracting parties does not restore what in virtue of the decree of annulment he is bound to return, the other cannot be compelled to comply with what is incumbent upon him. If the loss is due to the fault of the defendant, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. If the loss is due to the fault of the plaintiff, the action for annulment shall be extinguished. If the loss is due to fortuitous event, the contract can still be annulled, but the defendant can be held liable only for the value of the thing at the time of the loss without interest. The defendant, not the plaintiff, must suffer the loss because the defendant was still the owner of the thing at the time of the loss. The same is true if it is the plaintiff who cannot return the thing because it has been loss through fortuitous event. Unenforceable Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1403. The following contracts are unenforceable, unless they are ratified: 1. Those entered into in the name of another person by one who has been given no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers; 2. Those that do not comply with the Statute of Frauds as set forth in this number. In the following cases an agreement hereafter made shall be unenforceable by action, unless the same, or some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent; evidence, therefore, of the agreement cannot be received without the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents: a. An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER b. A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another; c. An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; d. An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum; e. An agreement for the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein; f. A representation as to the credit of a third person. 3. Those where both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract. Art. 1404. Unauthorized contracts are governed by article 1317 and the principles of agency in Title X of this Book. Art. 1405. Contracts infringing the Statute of Frauds, referred to in No. 2 of article 1403, are ratified by the failure to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the same, or by the acceptance of benefit under them. Art. 1406. When a contract is enforceable under the Statute of Frauds, and a public document is necessary for its registration in the Registry of Deeds, the parties may avail themselves of the right under Article 1357. Art. 1407. In a contract where both parties are incapable of giving consent, express or implied ratification by the parent, or guardian, as the case may be, of one of the contracting parties shall give the contract the same effect as if only one of them were incapacitated. If ratification is made by the parents or guardians, as the case may be, of both contracting parties, the contract shall be validated from the inception. Art. 1408. Unenforceable contracts cannot be assailed by third persons. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------108 Unenforceable Contracts Unenforceable Contracts – contracts which cannot be enforced by a proper action in court, unless they are ratified, because either they are entered into without or in excess of authority or they do not comply with the statute of frauds or both of the contracting parties do not possess the required legal capacity. Classes of Unenforceable Contracts 1. Contracts entered into in the name of another person by one without any authority or in excess of his authority; 2. Those which do not comply with the statute of frauds; and 3. Those where both of the contracting parties are legally incapacitated to give consent to a contract. Characteristics of Unenforceable Contracts 1. They cannot be enforced by a proper action in court; 2. They are susceptible of ratification; 3. They cannot be assailed by third persons. Unenforceable and Rescissible Contracts, Distinguished Unenforceable Contracts Rescissible Contracts As to Enforceability in Court Cannot be enforced by a Can be enforced, unless it proper action in court is rescinded As to Causes Causes for unenforceability Causes for rescissibility are are different from causes for different from causes for rescissibility unenforceability As to Susceptibility to Ratification Susceptible of ratification Not susceptible of ratification As to Action by Third Person Cannot be assailed by third May be assailed by third persons persons who are prejudiced Unenforceable and Voidable Contracts, Distinguished Unenforceable Contracts Voidable Contracts As to Enforceability in Court Cannot be enforced by a Can be enforced, unless it proper action in court is annulled As to Causes The causes for Causes for voidability are unenforceability are different from causes for different from causes for unenforceability voidability MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Contracts which are Unenforceable 1. Contracts entered into without or in Excess of Authority Contracts entered into in the name of another person by one who has been given no authority or legal representation, or one who has acted beyond his powers are unenforceable. Such contracts shall be governed by the principles of agency in Title X of the Civil Code. Hence, the following principles on agency are applicable: a. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter or unless he has a right to represent him. If he is duly authorized, he must act within the scope of his powers; b. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, is unenforceable; c. Such contract may be ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person in whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. 2. Contracts Infringing the Statute of Frauds The Statute of Frauds was enacted for the purpose of preventing frauds. Hence, it should not be made the instrument to further them. The provisions of the Statute of Frauds are applicable only to executor contracts not to executed contracts whether totally or partially. Form Required by the Statute – the only formality required under the Statute of Frauds is that the contract must be in writing and subscribed by the party charged or by his agent. “Subscribed” means signed by the party charged. “Party charged” is the party defendant in the case. Effect of Non-Compliance – in case of noncompliance with the statute of frauds, the contract is unenforceable by action. Therefore, what is affected by the defect of the contract is not its validity, but its enforceability. (Hence, unenforceable contracts are actually valid contracts, but they are not binding as the other party may just deny its existence). 109 Contracts Covered a. An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; b. A special promise to answer for the debt, default or miscarriage of another; Illustration: D borrowed P 500,000.00 from C. In a separate agreement, it was agreed that G will pay the debt to C in the event that D cannot pay the debt. In this case, the agreement with G (contract of guaranty) must comply with the requirements of the Statute of Frauds otherwise the contract of guaranty is unenforceable. Note: contract of suretyship (a contractual relation resulting from an agreement whereby one person, the surety, engages to be answerable to a third person for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another known as the principal) need not comply with the Statute of Frauds because unlike the guarantor, a surety binds himself as a principal debtor. c. An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; Illustration: marriage settlements and donations by reason of marriage must comply with the Statute of Frauds. d. An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five thousand pesos; e. An agreement for the leasing of property for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or an interest therein; Illustration: A sold to B a parcel of land for P 500,000.00. The sale must comply with the Statute of Frauds for it to be enforceable because the sale involves the sale of a parcel of land which is a real property. It must be noted however that even if the sale in this case was done orally and not in writing, the sale is still valid, but it cannot be enforced by a court action. f. A representation as to the credit of a third person Ratification – contracts infringing the Statute of Frauds are susceptible of ratification. They may be ratified either (1) by the failure to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the same; or (2) by the acceptance of the benefits under them. 3. Contracts where both Parties are Incapacitated MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Contracts where both parties are legally incapacitated are unenforceable. If only one of the parties is incapacitated, the contract is voidable. Contracts of this nature may be ratified expressly or impliedly. Ratification may be effected by the parents or guardians of the contracting parties, or by the contracting parties themselves upon attaining or regaining capacity. If the ratification was effected by the guardians or parents, the contract shall become voidable. If the ratification was effected by the contracting parties upon attaining or regaining capacity, the contract is validated. Void or Inexistent Contracts ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1409. The following contracts are inexistent and void from the beginning: 1. Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy; 2. Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious; 3. Those whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction; 4. Those whose object is outside the commerce of men; 5. Those which contemplate an impossible service; 6. Those where the intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained; 7. Those expressly prohibited or declared void by law. These contracts cannot be ratified. Neither can the right to set up the defense of illegality be waived. Art. 1410. The action or defense for the declaration of the inexistence of a contract does not prescribe. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Void or Inexistent Contracts Void or Inexistent Contract – one which lacks absolutely either in fact or in law one or some of the elements which are essential for its validity. Although used interchangeably, void and inexistent contracts are different from each other. Their distinction is important especially in connection with the application of the in pari delicto principle. 110 Void contracts – those where all of the requisites of a contract are present, but the cause, object or purpose, is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy or the contract itself is prohibited or declared by law to be void. The principle of in pari delicto is applicable only here. Hence, void contracts may actually produce legal effects. Inexistent contracts – those where one or some or all of those requisites which are essential for the validity of a contract are absolutely lacking, such as those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious. Inexistent contracts cannot produce any effect whatsoever. Void or Inexistent and Rescissible Contracts, Distinguished Void or Inexistent Rescissible Contracts Contract As to Nature As a rule, produces no Valid, unless rescinded effect. As to Defect Defect consists in absolute Defect consists in lesion or lack in fact or in law of one damage to one of the or some of the essential contracting parties or to elements of a contract third persons As to Basis The nullity or inexistence is The rescissible character is based in law based on equity As to Prescriptibility of Action The action for the The action for rescission of declaration of nullity or a contract is prescriptible inexistence does not prescribe As to Action by Third Persons As a rule, the nullity or May be assailed by third inexistence cannot be persons assailed by third persons. But their persons whose interests are directly affected may invoke the contracts nullity or inexistence Void or Inexistent Distinguished Void or Inexistent Contracts and Voidable Contracts, Voidable Contracts MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER As to Nature As a rule, produces no Binding, unless annulled effect As to Causes Causes for absolute nullity Causes for annullability are or inexistence are different different from causes for from causes for the absolute nullity or annullability inexistence As to Susceptibility of Ratification Not susceptible of Susceptible of ratification ratification As to Prescriptibility of Action The action for the The action for annulment of declaration of nullity or contract is prescriptible inexistence does not prescribe As to Action by Third Persons As a rule, the nullity or The annulability of the inexistence cannot be contract cannot be invoke assailed by third persons. third persons But persons whose interests are directly affected may invoke the contracts nullity or inexistence Void or Inexistent and Unenforceable Contracts, Distinguished Void or Inexistent Unenforceable Contracts Contracts As to Nature There is, in reality, no There is actually a contract contract at all which cannot be enforced by a court action, unless it is ratified As to Causes Causes for the inexistence Causes for the or absolute nullity are unenforceability are different from causes for the different from causes for the unenforceability of the absolute nullity or contract inexistence As to Susceptibility of Ratification Not susceptible of Susceptible of ratification ratification As to Action by Third Persons As a rule, the nullity or The unenforceability of the inexistence cannot be contract cannot be assailed assailed by third persons. by third persons 111 But their persons whose interests are directly affected may invoke the contracts nullity or inexistence Contracts which are Void or Inexistent 1. Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy (void); 2. Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious (inexistent); 3. Those whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction (inexistent); 4. Those whose object is outside the commerce of men (void); 5. Those which contemplate an impossible service (void); 6. Those where the intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained (void); 7. Those expressly prohibited or declared void by law (void) Examples: Articles 1490, 1491, 1689, 1782, 1799, 2035, 2088, and 2130 of the Civil Code, and Article 87 of the Family Code. Characteristics 1. As a general rule, they produce no legal effects whatsoever; 2. They are not susceptible of ratification; 3. The right to set up the defense of inexistence or absolute nullity cannot be waived or renounced; 4. The action or defense for the declaration of their inexistence or absolute nullity is imprescriptible; 5. The inexistence or absolute nullity of a contract cannot, as a rule, be invoked by a person whose interests are not directly affected. Effects – As far as inexistent contracts are concerned, they produce no legal effect whatsoever. However, void contracts where nullity proceeds from illegality of the cause or object can produce legal effects. Nullity of contracts due to illegal cause or object, when executed (and not merely executory), will produce the effect of barring any action by a guilty to recover what he has already given under the contract. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Art. 1411. When the nullity proceeds from the illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and the act constitutes a criminal offense, both parties being in pari delicto, they shall have no action against each other, and both shall be prosecuted. Moreover, the provisions of the Penal Code relative to the disposal of effects or instruments of a crime shall be applicable to the things or the price of the contract. This rule shall be applicable when only one of the parties is guilty; but the innocent one may claim what he has given, and shall not be bound to comply with his promise. Art. 1412. If the act in which the unlawful or forbidden cause consists does not constitute a criminal offense, the following rules shall be observed: 1. When the fault is on the part of both contracting parties, neither may recover what he has given by virtue of the contract, or demand the performance of the other's undertaking; 2. When only one of the contracting parties is at fault, he cannot recover what he has given by reason of the contract, or ask for the fulfillment of what has been promised him. The other, who is not at fault, may demand the return of what he has given without any obligation to comply his promise. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Principle of In Pari Delicto When the defect of a void contract consists in the illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and both of the parties are at fault or in pari delicto, the law refuses them every remedy and leaves them where they are. The principle presupposes that the fault of one party is more or less equal or equivalent to the fault of the other party. Where the unlawful act constitutes a criminal offense, the provisions of the Revised Penal Code relative to the disposal of effects or instruments of a crime shall be applied. Effect if only One Party is at Fault When only one of the contracting parties is at fault: a. Contract has already been executed The guilty party is barred from recovering what he has given to the other party by reason of the contract. However, the innocent party may demand for the return of what he has given. b. Contract merely executory 112 Neither of the contracting parties can demand for the fulfilment of any obligation arising from the contract nor be compelled to comply with such obligation. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1413. Interest paid in excess of the interest allowed by the usury laws may be recovered by the debtor, with interest thereon from the date of the payment. Art. 1414. When money is paid or property delivered for an illegal purpose, the contract may be repudiated by one of the parties before the purpose has been accomplished, or before any damage has been caused to a third person. In such case, the courts may, if the public interest will thus be subserved, allow the party repudiating the contract to recover the money or property. Art. 1415. Where one of the parties to an illegal contract is incapable of giving consent, the courts may, if the interest of justice so demands allow recovery of money or property delivered by the incapacitated person. Art. 1416. When the agreement is not illegal per se but is merely prohibited, and the prohibition by the law is designed for the protection of the plaintiff, he may, if public policy is thereby enhanced, recover what he has paid or delivered. Art. 1417. When the price of any article or commodity is determined by statute, or by authority of law, any person paying any amount in excess of the maximum price allowed may recover such excess. Art. 1418. When the law fixes, or authorizes the fixing of the maximum number of hours of labor, and a contract is entered into whereby a laborer undertakes to work longer than the maximum thus fixed, he may demand additional compensation for service rendered beyond the time limit. Art. 1419. When the law sets, or authorizes the setting of a minimum wage for laborers, and a contract is agreed upon by which a laborer accepts a lower wage, he shall be entitled to recover the deficiency. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Exceptions to the In Pari Delicto Principle 1. Payment of usurious interest. The law allows the debtor to recover the interest paid in excess of that allowed by the usury laws, with interest thereon from the date of payment (Note: the effectivity of the usury law is currently suspended) 2. Payment of money or delivery of property for an illegal purpose, where the party who paid or delivered MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER repudiates the contract before the purpose has been accomplished, or before any damage has been caused to a third person. The courts may allow such party to recover what he has paid or delivered, if the public interest will thus be subserved 3. Payment of money or delivery of property by an incapacitated person. The courts may allow such person to recover what he has paid or delivered, if the interest of justice so demands. 4. Agreement or contract which is not illegal per se but is merely prohibited by law, and the prohibition is designed for the protection of the plaintiff; The plaintiff, if public policy is hereby enhanced, may recover what he has paid or delivered. 5. Payment of any amount in excess of the maximum price of any articles or commodity fixed by law; The buyer may recover the excess. 6. Contract whereby a labourer undertakes to work longer than the maximum number of hours fixed by law; The labourer may demand for overtime pay. 7. Contract whereby a labourer accepts a wage lower than the minimum wage fixed by law. The laborer may demand for the deficiency. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1420. In case of a divisible contract, if the illegal terms can be separated from the legal ones, the latter may be enforced. Art. 1421. The defense of illegality of contract is not available to third persons whose interests are not directly affected. Art. 1422. A contract which is the direct result of a previous illegal contract, is also void and inexistent. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Natural Obligations ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1423. Obligations are civil or natural. Civil obligations give a right of action to compel their performance. Natural obligations, not being based on positive law but on equity and natural law, do not grant a right of action to enforce their performance, but after voluntary fulfillment by the obligor, they authorize the retention of what has 113 been delivered or rendered by reason thereof. Some natural obligations are set forth in the following articles. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Natural Obligations Natural Obligations – obligations based on equity and natural law, which do not grant a right of action to enforce their performance, but after voluntary fulfilment by the obligor, authorize the retention of what has been delivered or rendered by reason thereof. – Obligations without a sanction, susceptible of voluntary performance, but not through compulsion by legal means. Natural and Civil Obligations, Distinguished Natural Obligations Civil Obligations As to Basis Based on equity and natural Based on positive law law As to Enforceability by Court Action Not enforceable by court Enforceable by court action action Natural and Moral Obligations, Distinguished Natural Obligations Moral Obligations As to Presence of Juridical Tie There is a juridical tie There is no juridical tie between the parties which is, however, not enforceable by court action As to Effects of Fulfillment Voluntary fulfilment by the Voluntary fulfilment of moral obligor produces legal obligations does not effects which the courts will produce any legal effect recognize and protect which courts will recognize and protect Reasons for Regulation of Natural Obligations In all the specified cases of natural obligation recognized by the Civil Code, there is a moral but not a legal duty to perform or pay, but the person thus performing or paying feels in good conscience he should comply with his undertaking which is based on moral grounds. The law then should not permit him to change his mind and recover what he has delivered or paid; the law should compel him to abide by his honor and conscience. After all, equity, morality, and natural justice, are the abiding foundations of all positive law. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Furthermore, from the point of view of the payee, the incorporation of natural obligations into the legal system becomes imperative. Natural Obligations Specified by the Civil Code ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1424. When a right to sue upon a civil obligation has lapsed by extinctive prescription, the obligor who voluntarily performs the contract cannot recover what he has delivered or the value of the service he has rendered. Art. 1425. When without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, a third person pays a debt which the obligor is not legally bound to pay because the action thereon has prescribed, but the debtor later voluntarily reimburses the third person, the obligor cannot recover what he has paid. Art. 1426. When a minor between eighteen and twentyone years of age who has entered into a contract without the consent of the parent or guardian, after the annulment of the contract voluntarily returns the whole thing or price received, notwithstanding the fact that he has not been benefited thereby, there is no right to demand the thing or price thus returned. Art. 1427. When a minor between eighteen and twentyone years of age, who has entered into a contract without the consent of the parent or guardian, voluntarily pays a sum of money or delivers a fungible thing in fulfillment of the obligation, there shall be no right to recover the same from the obligee who has spent or consumed it in good faith. Art. 1428. When, after an action to enforce a civil obligation has failed the defendant voluntarily performs the obligation, he cannot demand the return of what he has delivered or the payment of the value of the service he has rendered. Art. 1429. When a testate or intestate heir voluntarily pays a debt of the decedent exceeding the value of the property which he received by will or by the law of intestacy from the estate of the deceased, the payment is valid and cannot be rescinded by the payer. Art. 1430. When a will is declared void because it has not been executed in accordance with the formalities required by law, but one of the intestate heirs, after the settlement of the debts of the deceased, pays a legacy in compliance with a clause in the defective will, the payment is effective and irrevocable. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------114 Estoppel ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1431. Through estoppel an admission or representation is rendered conclusive upon the person making it, and cannot be denied or disproved as against the person relying thereon. Art. 1432. The principles of estoppel are hereby adopted insofar as they are not in conflict with the provisions of this Code, the Code of Commerce, the Rules of Court and special laws. Art. 1433. Estoppel may in pais or by deed. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Estoppel Estoppel – a condition or state by virtue of which an admission or representation is rendered conclusive upon the person making it and cannot be denied or disproved as against the person relying thereon. Kinds of Estoppel 1. Estoppel in Pais 2. Estoppel by Deed or by Record 3. Estoppel by Laches Estoppel in Pais (or by Conduct) Estoppel which arises when one by his acts, representations, or admissions, or by his silence when he ought to speak out, intentionally or through culpable negligence, induces another to believe certain facts to exist and such other rightfully relies and acts on such belief, as a consequence of which h would be prejudiced if the former is permitted to deny the existence of such facts. Elements 1. One person makes acts, representations, or admissions, or kept his silence when he ought to speak out; 2. And such acts, representations, admissions, or silence, intentional or through culpable negligence, induces another to believe certain facts to exist; 3. Such another person rightfully relies and acts on such belief; 4. Such another person would be prejudiced if the person who made acts, representations, or admissions, is permitted to deny the existence of such facts. MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER Types a. Estoppel by Silence – a type of estoppel in pais which arises when a party, who has a right and opportunity to speak or act as well as a duty to do so under the circumstances, intentionally of through culpable negligence, induces another to believe certain facts to exist and such other relies and acts on such belief, as a consequence of which he would be prejudiced if the former is permitted to deny the existence of such facts. Illustration: A and B entered into a contract of sale whereby A agreed to buy from B a parcel of land of B for P 100,000.00. During the negotiation as well as when the agreement for the sale of the land was reached, C, the true owner of the parcel of the land was present. However, C merely kept his silence. In this case, C is precluded from asserting that the contract is invalid as he did not consent thereto being the true owner. b. Estoppel by Acceptance of Benefits – a type of estoppel in pais which arises when a party by accepting benefits derived from a certain act or transaction, intentionally or through culpable negligence, induces another to believe certain facts to exist and such other relies and acts on such belief, as a consequence of which he would be prejudiced if the former is permitted to deny the existence of such facts. Estoppel by Deed or by Record Strictly speaking, estoppel by deed and estoppel record are two distinct types of technical estoppel. Estoppel by Deed – a type of technical estoppel by virtue of which a party to a deed and his privies are precluded from asserting as against the other party and his privies any right or title in derogation of the deed, or from denying any material fact asserted therein. Estoppel by Record – a type of technical estoppel by virtue of which a party and his privies are precluded from denying the truth of matters set forth in a record whether judicial or legislative. 115 Estoppel by Judgment – a type of estoppels by record by virtue of which the party to a case is precluded from denying the facts adjudicated by a court of competent jurisdiction. It must not be confused with res judicata. Estoppel by judgment bars the parties from raising any question that might have been put in issue and decided in the previous litigation, whereas res judicata makes a judgment conclusive between the same parties as to the matter directly adjudged. Estoppel by Laches Laches – such neglect or omission to assert a right, taken in conjunction with lapse of time and other circumstances causing prejudice to an adverse party, as will operate as a bar in equity. – in a general sense, is failure to neglect, for an unreasonable and unexplained length of time, to do that which, by exercising due diligence, could or should have been done earlier; it is negligence or omission to assert a right within a reasonable time, warranting a presumption that the party entitled to assert it has abandoned it or declined to assert it. – a type of equitable estoppel which arises when a party, knowing his rights as against another, takes no step or delays in enforcing them until the condition of the latter, who has no knowledge or notice that the former would assert such rights, has become so changed that he cannot without injury or prejudiced, be restored to his former stated. Basis The doctrine of laches or of “stale demands” is based upon grounds of public policy which requires the discouragement of stale claims and, unlike the statute of limitations, is not a mere question of time, but is principally a question of the inequity or unfairness of permitting a right or claim to be enforced or asserted. Elements 1. Conduct on the part of the defendant, or of one under whom he claims, giving rise to the situation of which complaint is made and for which the complaint seeks a remedy; 2. Delay in asserting the complainant’s rights, the complainant having had knowledge or notice, of the defendant’s conduct and having been afforded an opportunity to institute a suit; MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts. OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS CIVIL LAW REVIEWER 3. Lack of knowledge or notice on the part of the defendant that the complainant would assert the right on which he bases his suit; and 4. Injury or prejudice to the defendant in the event relief is accorded to the complainant, or the suit is not held to be barred. Application The doctrine of laches is applicable even in void contracts, unlike prescription which has no application to void contracts. Illustration: A, a non-Christian, sold a parcel of land to X without executive approval as required by the Administrative Code. Despite the invalidity of the sale, A allowed X to enter, possess and enjoy the land in question without protest. Subsequently, A died. However, during the 20 years after the death of A, the successors of A remained inactive without taking any step to revindicate the property. In this case the successors cannot any more claim the property on the ground that the contract between A and X is void. They are already barred by laches. Laches and Prescription, Distinguished Laches Prescription Concerned in the effects of Concerned with the fact of delay delay Principally a question of Prescription is a question or inequity or permitting a matter of time claim to be enforced, this inequity being founded on some changes in the condition of the property or the relation of the parties Laches is not statutory Prescription is statutory Laches applies in equity Prescription applies at law Art. 1435. If a person in representation of another sells or alienates a thing, the former cannot subsequently set up his own title as against the buyer or grantee. Art. 1436. A lessee or a bailee is estopped from asserting title to the thing leased or received, as against the lessor or bailor. Art. 1437. When in a contract between third persons concerning immovable property, one of them is misled by a person with respect to the ownership or real right over the real estate, the latter is precluded from asserting his legal title or interest therein, provided all these requisites are present: 1. There must be fraudulent representation or wrongful concealment of facts known to the party estopped; 2. The party precluded must intend that the other should act upon the facts as misrepresented; 3. The party misled must have been unaware of the true facts; and 4. The party defrauded must have acted in accordance with the misrepresentation. Art. 1438. One who has allowed another to assume apparent ownership of personal property for the purpose of making any transfer of it, cannot, if he received the sum for which a pledge has been constituted, set up his own title to defeat the pledge of the property, made by the other to a pledgee who received the same in good faith and for value. Art. 1439. Estoppel is effective only as between the parties thereto or their successors in interest. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Laches is not based on Prescription is based on fixed time fixed time ------------------------------------------------------------------------------Art. 1434. When a person who is not the owner of a thing sells or alienates and delivers it, and later the seller or grantor acquires title thereto, such title passes by operation of law to the buyer or grantee. 116 MAGHIRANG, Ariel | REFERENCES: Jurado, Tolentino | 2011 Civil Law Reviewer: Obligations and Contracts.