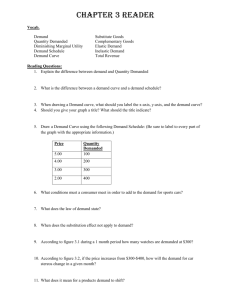

AS Microeconomics Textbook: Scarcity, Production, and More

advertisement