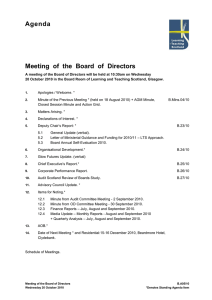

Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of High Technology Management Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/hitech Earnings manipulations and board's diversity: The moderating role of audit ⁎ Amel Kouaiba,b, , Abdullah Almulhima a b King Faisal University, Department of Accounting, Saudi Arabia Faculty of Economics and Management of Sfax, Department of Accounting, Tunisia A R T IC LE I N F O ABS TRA CT Keywords: Gender diversity Directors' nationality Audit index Earnings management Europe This paper analyzes whether an audit index moderates the relationship between boardroom composition (gender diversity and foreign directors) and earnings-management activities in the European context. Data from a sample of 429 European firms listed on Stoxx Europe 600 Index from 1998 to 2017 are used to test a moderation model. Evidence reveals that board gender diversity is negatively associated with both accruals-based and real earnings management activities, while non-European directors are positively associated with the earnings-management activities. Further, audit index significantly moderates the link between board diversity and earnings-management. This study is unique in providing European evidence for the moderating effect of audit quality on the link between the demographic features of board members and the firm outcome. This paper is also relevant as it develops a composite index of audit quality. 1. Introduction Academic researchers have recognized significant variations in individuals' diversity, dictated by gender and ethnic group that can affect corporate decision-making processes (Duong & Evans, 2016; Harris, Karl, & Lawrence, 2019; Lakhal, Aguir, Lakhal, & Malek, 2015; Reggy, Niels, Lars, & Trond, 2019). Females have been observed to be more risk averse and more independent-minded than their male counterparts (Lago, Delgado, & Castelo Branco, 2018; Adams & Funk, 2012). Consequently, females exhibit a high oversight level. The presence of foreign directors on a corporate board enhances board competency due to their different exposure in terms of governance practices, knowledge, skills, and culture representativeness (Miletkov, Poulsen, & Wintoki, 2017; Reggy et al., 2019; Ruigrok, Peck, & Tacheva, 2007). Since foreign directors are not connected with closed domestic networks, they tend to become independent from management, which signals to investors that the firm is professionally managed and that their rights are safeguarded. Consistent with agency theory, it is important for resource-rich composed boards to have an expanded audit scope to protect the reputational capital. A significant relationship is thus established between board diversity, e.g. ethnicity and gender, and the choice of auditor (Ahmad, Houghton, & Yusof, 2006). Culturally diverse boardroom directors, when correctly pooled together, are considered as assets through which group processes can be improved and solutions to problems can be found. However, demographic diversity among directors may also generate conflicts due to information asymmetry and low commitment among members. The consequences of corporate governance failures have caused regulators to examine how boardroom composition and functions could be reformed to provide an effective monitoring function (Ararat, Aksu, & Cetin, 2015). Although many studies have examined board ⁎ Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: akauaib@kfu.edu.sa (A. Kouaib), amalmulhem@kfu.edu.sa (A. Almulhim). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2019.100356 1047-8310/ © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Please cite this article as: Amel Kouaib and Abdullah Almulhim, Journal of High Technology Management Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2019.100356 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim structure and demographic diversity, empirical findings have been inconsistent and cannot be extended to other contexts. Further, research on audit characteristics and their effects on the relationship between boardroom diversity and earnings-management techniques have, to the best of our knowledge, yet to receive sufficient empirical attention. Consistent with agency theory and resource dependency theory, this paper extends this area of research by studying the effects of boards' diversity on earnings-management activities and whether audit quality moderates these effects. This study specifically focuses on the moderating role of audit functions and provides European evidence. The sample used comprises 429 non-financial listed European firms during the period 1998–2017. This paper suggests that the Europe region is particularly useful as a context for such research, as the legislative body of the European Union advocates for a gender threshold that requires 40% of a company's non-executive directors to be female. At the same time, the European accounting standardization IAS/IFRS brings harmonization among firms with different institutional frameworks and enforcement regulations. European firms are also well suited to the purpose of the present study, as internationalization has led to boards becoming more international. This paper is also relevant as it develops a composite index of audit measures. In fact, investigating the performance outcomes of single audit attributes is equivocal (Ararat et al., 2015). Therefore, audit index is operationalized by combining different proxies used in prior studies. The present paper argues that much insight into the studied link could be gained by combining these different proxies. The article analyzes whether an audit index moderates the relationship between board composition (gender and nationality board diversity) and earnings management activities. Gender diversity is found to be negatively related and nationality positively related. The audit index moderates both relationships, which become more negative in the case of gender diversity, and lower in the case of nationality diversity. This study contributes to the growing literature on board characteristics and auditing in three ways. First, it is important to test the effects of gender diversity in a context that has enforced legislations to increase female representation in boardrooms since the benefits that female directors bring to the firm have not been conclusively proven. Second, prior studies that have examined the effects of foreign directors on firm performance have produced mixed results (Arun, Almahrog, & Aribi, 2015a, 2015b; Estelyi & Nisar, 2016; Masulis, Wang, & Xie, 2012; Miletkov et al., 2017; Reggy et al., 2019). This research focuses on the effects of board members' nationality on earnings-management activities. Reggy et al. (2019) tested this relationship but focused only on the effects of the board internationalization on accrual-based earnings management (hereafter AEM) activities. The present paper extend this work by testing these effects on AEM and real earnings management (hereafter REM). The focus on both earnings-management strategies is important since these manipulations can be extremely value destroying. Further, the potential role of having non-European members on the board has not previously been explored. The present paper adds to the literature on board internationalization. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical background, followed by the literature review and development of the hypotheses in Section 3. The research design is presented in Section 4 and the empirical findings are presented in Section 5. Section 7 concludes the paper after providing some robustness checks in Section 6. 2. Theoretical framework The board of directors is a very important element in internal corporate governance mechanisms. It is responsible for guiding, authorizing, and setting the company's strategic aims, including mergers, acquisitions, alliances, hiring/firing executives, capital structures, and also performs the critical functions of monitoring and advising top management (Coles, Daniel, & Naveen, 2008; Terjesen, Couto, & Francisco, 2016). Agency theory is one of the important theories that describes and explains corporate-governance mechanisms (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen and Meckling Jensen & Meckling, 1976). It underscores the importance of boardroom diversity in ensuring an effective and independent board monitoring function. The board of directors is unique in having the ability and power to mitigate and reduces agency conflicts between shareholders and top management by keeping separate the management and control aspects of the decisionmaking process. The board of directors is empowered by the shareholders to exercise ultimate control over top management. The agency literature recognizes that the board of directors is one of several mechanisms that can mitigate and reduce agency conflicts within the firm. Resource dependence theory is another theory that describes corporate governance mechanisms. Pfeffer (1978) developed this theory with the central idea being that firms attempt to exert control over their environment by co-option of the resources needed to survive (Muth & Donaldson, 1998). The main objective of this theory is to maximize organizational autonomy. Organizational leaders use a variety of strategies to manage external constraints and dependencies. The function of this theory refers directly to the ability of the board to bring resources to the firm (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, 2009). Wernerfelt (1984) provided some examples of these resources, including brand names, in-house knowledge of technology, capital, efficient procedures, and the employment of skilled personnel. The resource dependence, theory establishes the significant role played by the board of directors in connecting a firm with the external resources needed for its survival; hence, the need exists for boardroom structures to be a reflection of the society in which it operates. Resource dependence theory proposes that the board of directors is a mechanism for managing external dependencies (Pfeffer, 1978). The board plays a vital role in providing or securing essential resources through linkages to the external environment (Boyd, 1990). Pfeffer, 1978, p. 163) stated that “when an organization appoints an individual to a board, it expects the individual will come to support the organization, will concern himself with its problems, will variably present it to others, and will try to aid it.” The authors also asserted that the board can provide four primary benefits: advice and counsel; legitimacy; a channel for communicating information between external organizations and the firm; and professional access to commitment and/or supports from important 2 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim elements outside the firm. In this sense, Cadbury (2002) described the board of directors as a bridge between stakeholders and directors. When the bridge is well built, the ensuing high level of care will enhance performance, reduce earnings management, and increase disclosure and transparency. Agency theorists suggest that boards dominated by inside directors may be less vigilant monitors of management as these directors may intentionally provide self-serving accounts of managerial actions to enhance their status (Eisenhardt, 1989; Fama, 1980). Agency theory researchers have discussed the dangers of too close a relationship between executive and non-executive directors and the collusion that this might imply (Almulhim, 2014). According to this theory, an effective board should comprise outside directors who provide superior performance to the firm because of their independence from the managers (Dalton, Daily, Ellstrand, & Johson, 1998). Kyaw, Olugbode, and Petracci (2015) investigated the effect of board gender diversity (hereafter BGD) on earnings management in European countries. They used a sample consisting of all European companies for which BGD data were available in the Thomson Reuters Asset4 database and accounting data were available in the DataStream from 2002 to 2013. The authors used the magnitude of accruals as a proxy for the extent to which managers exercise discretion in reporting earnings. Findings revealed that a genderdiverse board mitigated earnings management in countries in which gender equality was high. Damak (2018) investigated the influence of BGD on earnings management for a sample of 85 companies listed in the SBF120 over the period 2010–2014. Results showed a significant negative effect of women's presence on the board on earnings management. This finding supports the efforts made by French political bodies to increase gender diversity on corporate boards and might inspire political actors of other countries to take initiatives to regulate and/or promote women's appointment to boards of directors. 3. Related literature and hypotheses development The board of directors and its characteristics as corporate governance mechanism have been associated with earnings-management activities. Academic researchers have recognized the influence of resource-rich composed boards of directors in providing critical resources needed by their firms. They have investigated the consequences of board composition and shown the link with financial disclosures and earnings-management practices (Armstrong, Core, & Guay, 2014; Dechow, Sloan, & Sweeney, 1996; Gul & Leung, 2004; Gul, Srinidhi, & Ng, 2011; Xie, Davidson, & Dadalt, 2003). Under gender socialization theory, men and women bring varying beliefs, ethical views, and attitudes to the workplace because gender roles are dictated during childhood and strengthened over time through social standards (Eagly, Karau, & Makhijani, 1995; Dawson, 1992; Eagly, 1987; Gilligan Gilligan, 1982). In this line, previous literature has recognized that men and women have different cognitive frames in various areas (Arun et al., 2015a, 2015b; Pan & Sparks, 2012; Post & Byron, 2015), including women having higher ethical standards for their companies and being more cautious in the context financial decision-making. The effect of female presence on corporate boards in different aspects of management (risk aversion, firm performance, financial reporting quality, etc.) has been widely investigated (Adams, Gupta, & Leeth, 2009; Faccio, Marchica, & Mura, 2016; Gavious, Segev, & Yosef, 2012; Srinidhi, Gul, & Tsui, 2011). “Gendered identity standards” motivate men to behave in more aggressive and less nurturing ways than women (Byrnes, Miller, & Schafer, 1999; Kroska, 2014). Therefore, female presence on corporate boards is associated with low levels of earnings manipulations because they tend to reduce information asymmetry and do not engage in unethical conduct to gain private benefits (Abad, Lucas-Pérez, Minguez-Vera, & Yagüe, 2017; Lakhal et al., 2015; Pan & Sparks, 2012). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed: H1. There is a negative association between board gender diversity and the level of earnings management. The presence of foreign directors (those from outside Europe) may influence the quality of board's monitoring and, therefore, firm outcomes (Masulis et al., 2012; Miletkov et al., 2017; Oxelheim, Gregoric, Randøy, & Thomsen, 2013). The presence of foreign directors can help to curb earnings management by increasing the independence of the board of directors. Culturally diverse boardroom directors, when correctly pooled together, are considered as asset through which group processes can be improved and solutions to problems can be found. This makes them more independent and better monitors to critically scrutinize management (Chiu, Oxelheim, Wihlborg, & Zhang, 2016; Du, Jian, & Lai, 2017; Miletkov et al., 2017). However, demographic diversity among directors may generate conflicts due to information asymmetry and low commitment among members, which leads to less effective monitoring and increases the level of earnings management. Europe has been a pioneer in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) adoption since 2005. Hence, a high level of knowledge of European accounting rules is needed to detect and mitigate manipulations in financial statements. However, non-European directors may be less familiar with accounting standards, impairing their ability to evaluate the level of opportunism in the manager's judgment in financial reporting. Indeed, both accounting expertise and accounting literacy are associated with lower AEM and REM levels post-IFRS adoption (Kouaib, Jarboui, & Mouakhar, 2018). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed: H2. Directors' nationality is significantly associated with levels of earnings management. Academic researchers have investigated the influence of some directors' diversity, e.g. gender and ethnicity, on audit outcome. They have provided supporting evidence that gender and ethnic composition of the boardroom affect audit fees (Johl, Subramaniam, & Zain, 2012; Yatim, Kent, & Clarkson, 2006). The board, through its audit committee, is responsible for choosing the auditors and negotiating the extent and intensity of auditing. Therefore, a board that is intent on improving the firm's governance is likely to choose a high-quality auditor and contract with the auditor to conduct an intensive service to improve the accuracy and reliability of the financial statements. To strengthen the argument, several studies have examined the relationships between corporate boards and 3 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Audit Board Gender AEM Board EM Board Nationality REM Fig. 1. Moderation model. Notes: This figure explains the role of audit on the link between board of directors' traits and earnings-management techniques. EM = earnings management; AEM = accrual earnings management; REM = real earnings management. auditors' efforts, finding significant association between the board's ethnic/gender diversity and the choice of auditor (Ahmad et al., 2006; Carcello, Hermanson, Neal, & Riley Jr, 2002; Karen, Srinidhi, Gul, & Tsui, 2017). The argument is that an independent and diligent board will demand a high-quality audit service due to the incentive to protect board reputational capital, reduce board litigation risks, and safeguard shareholder interests (Carcello et al., 2002; Fama & Jensen, 1983). To test the moderating effect of the audit service on the link between boardroom characteristics and earnings management practices, the following hypothesis is proposed: H3. Audit service significantly moderates the relationship between boardroom diversity and earnings-management activities. 4. Research design and methodology 4.1. Sampling and model specifications The initial sample consisted of 11,980 firm-year observations indexed on the Stoxx Europe 600 Index, for which audit, board members' gender, and accounting data were available in the DataStream and Thomson Reuters Asset4 databases. Data were collected manually regarding board members' nationality from the Bloomberg website. The intersection of the complete data collected resulted in a final sample of 429 European firms for the period 1998–2017. Observations from the year 2002 were not included because this year is associated with: the fall of the Arthur Andersen audit firm; and non-audit service restrictions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. These two events may have undue effects on the firms and the audit process. Further, the sample is made up of the European model, where the adoption of IFRS has been mandatory since 2005 and was voluntary before this year. Therefore, following Capkun, Collins, and Jeanjean (2016), the IFRS' switch year was not included to remove the adoption effect [1]. Fig. 1 represents the model used to answer the research question. To identify the moderating effect of audit index on the relationship between board members' diversity and earnings management strategies, we apply the Moderated Regression Analysis (MRA) method. Hence, we test the hypotheses using the following three regressions: EMit = a0 + a1 BGDit + a2 DNATit + ∑ Control Variables + ∑ Fixed EffectsBasic Model (1) EMit = a0 + a1 BGDit + a2 DNATit + a3 AINDEXit + ∑ Control Variables + ∑ Fixed Effects Basic Model (2) EMit = a0 + a1 BGDit + a2 DNATit + a3 AINDEXit + a4 BGD × AINDEXit + a5 DNAT × AINDEXit + ∑ Control Variables + ∑ Fixed Effects Interaction Model. Where: Dependent variable EM Independent variables BGD DNAT AINDEX Control variables FSIZE LEV DUAL PROF ACOM Earnings management: Either accruals-based earnings management or real earnings management. Board gender diversity: Percentage of women on the board of directors. Directors' nationality: Indicator variable coded one if at least one non-European sits on the board of directors, and zero otherwise. Audit index composed of three audit characteristics: EFFORT, TENURE, and INDEP. Firm size: Natural logarithm of total assets. Leverage ratio: Total debt to total equity. CEO duality: Indicator variable coded one if the CEO serves as the board chairman, and zero otherwise. Firm profitability: Return on assets in year t. Audit committee: Indicator variable coded one if the company have an audit committee, and zero otherwise. 4 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim MTBV MANDAT Fixed effects Market to book ratio: Market value divided by the book value. Indicator variable that takes on a value of one for firm-years if the firm did not adopt IFRS before the mandatory adoption date, 2005. Series of dichotomous variables for years, countries, and industries. 4.2. Variables measurement 4.2.1. Measuring earnings management We refer to the performance-matched discretionary accruals model introduced by Kothari, Leone, and Wasley (2005) to compute for discretionary accruals (DA). DA is defined as the absolute magnitude of the difference between total accruals (TA) and nondiscretionary accruals (NDA). We compute TA by referring to the net cash flow from operations reported in the cash flows statement and we use the following OLS regression to estimate the normal level of accruals: TAt = α1 1 ΔREV PPE + a2 + a3 + a4 (ROAt − 1) + εt Model (1) At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 A is total assets. ΔREV is the change in revenues. PPE is the amount of property, plant, and equipment. ROA is the net income before extraordinary items divided by lagged total assets. Then, DA are estimated as follow: t = a1̂ 1 + a2̂ ΔREV + a3̂ PPE + a4̂ (ROAt − 1) Model (2) NDA At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 The expected sign on a2̂ is positive, as changes in revenues are expected to be positively related to changes in working capital accounts. The a3̂ coefficient is predicted to be negative since that the level of fixed assets is expected to drive depreciation expenses and deferred taxes (Klein, 2002). To measure the extent of REM, we rely on the prior studies that developed proxies (Cohen, Dey, & Lys, 2008; Gunny, 2010; Kouaib & Jarboui, 2017; Roychowdhury, 2006; Zang, 2012). The first step is to estimate the normal level. It represents the ordinary behavior associated with the normal business operations. We develop an expectation model for the normal levels of cash flow from operations (Model 3), production costs (Model 4), R&D expenditures (Model 5), and SG&A expenditures (Model 6) as follow: CFOt 1 S ΔSt = a0 + αt + β1 + β2 + εtCFO Model (3) At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 PRODt 1 S ∆St ∆S = a0 + a1 + β1 MVt + β2 Qt + β3 t + β4 + β5 t − 1 + εtPROD Model (4) At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 RDt 1 INTt RDt − 1 = a0 + a1 + β1 MVt + β2 Qt + β3 + β4 + εtR & D Model (5) At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 SGAt 1 INTt ∆St ∆St = a0 + a1 + β1 MVt + β2 Qt + β3 + β4 + β5 ∗ DD + εtSG & A Model (6) At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 At − 1 where: CFO is cash flows from operations. At-1 is total assets at the beginning of the year t. S is net sales. ΔS is change in net sales. PROD is the sum of cost of goods sold and change in inventory during the year. MV is natural log of market value (MV = Price × Common shares outstanding). Q is Tobin's Q (Q = (MV + Debt + Preffered stock) / total assets). RD is R&D expense; we replace data on missing or negative R&D observations with zero to help increasing the sample size. INT is internal funds (INT = Income before extraordinary items + R&D expense + depreciation and amortization). SGA is SG&A expense. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles of their distribution to avoid the influence of outliers. The second step is to calculate abnormal levels that correspond to the difference between the actual values (CFO, PROD, R&D, and SG&A) and the normal values predicted from the models cited above. A low value of abnormal operating cash flows and discretionary expenses would indicate income-increasing REM. To have a comprehensive metric and capture the total effect of REM, we aggregate the four individual measures of real manipulation activities into one index (REMI). We multiply the abnormal operating cash flows by (−1). Therefore, the higher values indicate greater amounts of operating cash flows reduced by the firms to manage earnings upwards. In addition, we multiply the abnormal discretionary expenses (R&D and SG&A) by (−1). Therefore, the higher values indicate greater amounts of discretionary expenditures cut by the firms to increase reported earnings (Cohen & Zarowin, 2010). 4.2.2. Measuring audit index (AINDEX) Variations in stakeholder perspectives make it difficult to reach an agreement on a single and universal definition of audit quality. Therefore, a wide range of research has considered audit quality differently, focusing on one or more of the many proxies. The present research assumes that no single attribute should be considered as having the dominant influence on audit quality. To provide a full image of audit quality and, according to the data availability, an audit index was constructed by introducing three observable proxies to measure the overall audit quality. The first component is audit effort (EFFORT). Audit effort can be reflected by the number of days spent by the audit team to complete the entire audit process, including audit planning, fieldwork, and review, or by the audit fees. Higher audit fees reflect more 5 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Table 1 Descriptive statistics. Variables Mean Dependent variables AEM REMI AbnCFO AbnPROD AbnRD AbnSGA Independent variable BGD Control variables FSIZE LEV PROF MTBV Std. Dev. Percentiles 25% 50% 75% Skewness Kurtosis 0.0191 −0.0222 0.0193 −0.0004 0.0024 0.0334 0.0239 0.0603 0.0526 0.0345 0.0194 0.1224 0.0029 −0.0575 −0.0068 −0.0094 −0.0044 −0.0146 0.0059 −0.0162 0.0078 0.0008 0.0035 0.0010 0.0326 0.0165 0.0436 0.0097 0.0093 0.0199 1.3810 −0.5279 0.7624 −0.0802 −0.0078 2.5202 3.6114 3.5952 4.1131 3.1669 6.3404 8.3538 0.2350 0.1311 0.1440 0.2100 0.3100 1.0341 4.4188 15.2384 2.8594 0.0664 2.7322 1.8457 5.7112 0.0824 2.4951 14.035 0.0513 0.0300 1.2400 15.29 0.2562 0.0600 1.9800 16.59 1.5949 0.0900 3.2400 −0.2977 2.1573 0.3033 2.7266 2.8921 6.1148 25.3268 12.4337 Notes: AEM = accruals-based earnings management; REMI = real earnings management index; AbnCFO = abnormal levels of operating cash flows; AbnPROD = abnormal levels of production costs; AbnRD = abnormal levels of R&D expenditures; AbnSGA = abnormal levels of SG&A expenditures; BGD = board gender diversity; FSIZE = firm size; LEV = firm leverage ratio; PROF = firm profitability; MTBV = market-to-book ratio. auditor effort and higher audit quality (O'Sullivan, 2000). Further, it is expected that more audit work is required to ensure that the financial statements are free from material misstatement (Deis & Giroux, 1996). Therefore, the coefficient on EFFORT is predicted to be negative. EFFORT is an indicator variable that takes the value 1 if the natural logarithm of audit-related service fees is above the annual median fee, and 0 otherwise. The second component is audit tenure (TENURE). According to Hakim and Omri (2010), audit firm tenure can assess audit quality. This study primarily examines whether the length of the relationship between auditor and client could impair auditor independence. This is the major argument for auditor rotation on a regular basis. TENURE is an indicator variable that takes the value 1 if the number of consecutive years that the auditor audits the firm's financial statements is below the median of the auditor independence rotation for a given year, and 0 otherwise. Auditor independence rotation is defined as the number of years after which the company rotates its statutory auditor. The third component is auditor independence (INDEP). Non-audit services are likely to impair auditor independence (Frankel, Johnson, & Nelson, 2002). Therefore, lower audit quality should be observed with higher non-audit fees. INDEP is an indicator variable that takes the value 1 if the natural logarithm of non-audit service fees is below the annual median fee, and 0 otherwise. Accordingly, AINDEX equals 3 denotes a higher audit quality. Based on previous research, the coefficients on TENURE and INDEP are expected to be positive. 5. Results 5.1. Summary statistics Tables 1 and 2 present summary statistics for variables used in the paper. Table 1 depicts sample mean, standard deviation, 25th, Table 2 Sample division by gender and country. No. Abbreviation County Firms % Average females (%) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Total SE DK FI NL FR UK BE IE LU ES DE AT IT PT Sweden Denmark Finland Netherlands France United Kingdom Belgium Ireland Luxembourg Spain Germany Austria Italy Portugal 35 29 31 32 61 119 24 10 12 21 66 19 15 18 492 7.11 5.89 6.30 6.50 12.40 24.19 4.88 2.03 2.44 4.27 13.41 3.86 3.05 3.66 100 28 26 23 23 22 22 21 21 20 19 18 18 15 11 21 6 DE AT 11% 15% 18% IE 18% BE 20% UK 21% FR 21% 22% 23% NL 22% 23% 28% 26% FI 19% Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim SE DK LU ES IT PT Fig. 2. Sample division by gender and country. Notes: This figure presents the percentage of women's representation in European boardrooms. SE = Sweden; DK = Denmark; FI = Finland; NL = Netherlands; FR = France; UK = United Kingdom; BE = Belgium; IE = Ireland; LU = Luxembourg; ES = Spain; DE = Germany; AT = Austria; IT = Italy; PT = Portugal. 50th, and 75th percentiles, skewness and kurtosis. All the non-indicator variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels to eliminate extreme observations. Please refer to the Appendix for the variables' measures. Descriptive analysis revealed that the mean and median values of AEM were 0.0191 and 0.0059, respectively. The mean (median) from REMI was −0.0222 (−0.0162). The mean residuals from the four proxies of REMI were not zero. The mean value from BGD was 0.2350 coupled with a standard deviation value of 0.1311. The skewness data for most variables were relatively near to 0, indicating that the distributions were symmetrically distributed. Skewness greater than 0 indicates that the distribution for the variables is positively skewed. For distributions that have a long left tail (negatively skewed) can, for investors, mean extremely negative outcomes. Kurtosis provides information on how tall and sharp the central peak is. The kurtosis data for the variables AbnRD, AbnSGA, LEV, PROF, and MTBV were greater than 3, which leads to a leptokurtic distribution. Kurtosis of 8.3538 units for the AbnSGA and of 6.3404 for the AbnRD, compared to the benchmark of 3 units, suggested high levels of REM practices among the sampled firms. Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the average number of women on corporate boards covered in the study throughout the 18-year period of 2000 to 2017. As shown, Sweden and Denmark had the highest share of women on company boards, with an average of 28% and 26% seats, respectively. Finland, Netherlands, France, and the UK were the next best represented. The country where the most improvement in female hiring is needed is Portugal (11%). Correlations among the variables are presented in Table 3, showing that the highest correlation was observed between REMI and AbnCFO with a coefficient of 0.7685 (Pearson matrix) and 0.6798 (Spearman matrix). The coefficient is significant at the 1% level and the correlation is mechanical because AbnCFO is a component of REMI (Zang, 2012). The significantly positive correlations between the four proxies of REM techniques indicate that firms use the four types of REM at the same time. All other correlation coefficients were less than 0.7 and higher than −0.7, the rule of thumb representing serious multicollinearity problem in the statistical analysis. 5.2. Multivariate analysis 5.2.1. Estimation of the normal levels of earnings-management models The estimated residuals from the relevant estimation models measured the abnormal levels. Table 4 presents estimations of the normal levels of discretionary accruals, operating cash flow, production costs, R&D discretionary expenditures, and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) discretionary expenditures. As expected for model 1, the sign on a2̂ was positive and the sign on a3̂ was negative. Table 4 also reports on the explanatory power for each model. The best model to detect REM is the production-costs model. 5.2.2. Main results Following Zedeck (1971) and Sharma, Durand, and Arie (1981), the moderation analysis consisted of three steps. First, the unmoderated regression was estimated with only the predictor variables (board diversity). Second, the unmoderated regression was estimated by incorporating the moderating variable (AINDEX) into the model. Third, the moderated relationship was estimated by adding the product term. This analytical approach maintains the integrity of a sample and provides a basis for controlling the effects of a moderating variable, which modifies the form of the relationship. Table 5 displays results from these three steps. Panel data methodologies are used to estimate the models in this Table. Controls for the existence of unobserved fixed determinants and corrections to obtain robust standard errors are done. 7 8 1.0000 0.0131 −0.0118 0.0091 −0.0179 −0.0460⁎⁎⁎ −0.0534⁎⁎⁎ −0.0278⁎⁎ 0.0006 0.0284⁎⁎ −0.0273⁎⁎ 0.0128 ⁎ 0.0195 1.0000 0.6798⁎⁎⁎ 0.3418⁎⁎⁎ 0.2616⁎⁎⁎ 0.0351⁎⁎⁎ 0.0024 −0.0470⁎⁎⁎ 0.0092 −0.0263⁎⁎ 0.0045 0.0126 REMI ⁎⁎⁎ −0.0310 0.7685⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 0.2684⁎⁎⁎ 0.0940⁎⁎⁎ 0.0401⁎⁎⁎ 0.0246⁎ 0.0838⁎⁎⁎ −0.0112 0.0359⁎⁎⁎ −0.0158 0.0005 AbnCFO −0.0127 0.4124⁎⁎⁎ 0.1716⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 0.2078⁎⁎⁎ 0.0327⁎⁎⁎ 0.0491⁎⁎⁎ 0.0545⁎⁎⁎ −0.0270⁎⁎ 0.0241⁎ −0.0051 0.0157 AbnPROD 0.0010 0.2858⁎⁎⁎ 0.0203⁎ 0.0340⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 0.0829⁎⁎⁎ 0.0571⁎⁎⁎ 0.0565⁎⁎⁎ −0.0476⁎⁎⁎ 0.0241⁎ 0.0106 −0.0152 AbnRD 0.0063 0.0373⁎⁎⁎ 0.0474⁎⁎⁎ 0.0171 0.0231⁎ 1.0000 0.0908⁎⁎⁎ −0.0992⁎⁎⁎ −0.1068⁎⁎⁎ 0.0706⁎⁎⁎ 0.1158⁎⁎⁎ 0.0745⁎⁎⁎ AbnSGA −0.0009 0.0030 0.0161 0.0368⁎⁎⁎ 0.0310⁎⁎⁎ 0.0566⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 0.1827⁎⁎⁎ −0.0209⁎ −0.0167 0.0005 0.0111 BGD ⁎⁎⁎ −0.0310 −0.0481⁎⁎⁎ 0.0711⁎⁎⁎ 0.0438⁎⁎⁎ 0.0344⁎⁎⁎ 0.0311⁎⁎ 0.1479⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 −0.0791⁎⁎⁎ 0.1150⁎⁎⁎ −0.0379⁎⁎⁎ −0.0655⁎⁎⁎ AINDEX −0.0044 −0.0073 0.0177⁎ 0.0009 −0.0238⁎⁎ −0.1196⁎⁎⁎ −0.0430⁎⁎⁎ −0.0775⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 −0.5998⁎⁎⁎ 0.0014 −0.0234⁎ FSIZE ⁎⁎ 0.0214 −0.0008 −0.0167 −0.0140 0.0229⁎⁎ 0.0555⁎⁎⁎ 0.0468⁎⁎⁎ 0.1195⁎⁎⁎ −0.4795⁎⁎⁎ 1.0000 −0.0356⁎⁎⁎ 0.0352⁎⁎⁎ LEV −0.0142 0.0017 −0.0025 0.0119 0.0225⁎⁎ 0.1305⁎⁎⁎ 0.0070 −0.0121 0.0165 −0.0076 1.0000 0.0506⁎⁎⁎ PROF 0.0118 0.0145 0.0107 0.0287⁎⁎⁎ −0.0230⁎⁎ 0.0514⁎⁎⁎ 0.0152 −0.0326⁎⁎⁎ −0.0206⁎ 0.0196⁎ 0.0272⁎⁎ 1.0000 MTBV Notes: AEM = accruals-based earnings management; REMI = real earnings management index; AbnCFO = abnormal levels of operating cash flows; AbnPROD = abnormal levels of production costs; AbnRD = abnormal levels of R&D expenditures; AbnSGA = abnormal levels of SG&A expenditures; BGD = board gender diversity; FSIZE = firm size; LEV = firm leverage ratio; PROF = firm profitability; MTBV = market-to-book ratio. Measurements are summarized in the Appendix. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. AEM REMI AbnCFO AbnPROD AbnRD AbnSGA BGD AINDEX FSIZE LEV PROF MTBV AEM Table 3 Pearson (upper triangle) and spearman (lower triangle) correlation matrices. A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Table 4 Estimation of the normal levels of total accruals, operating cash flow, production costs, R&D expense, and SG&A expense. Model 1: accruals accrualsit/At–1 Model 2: CFO CFOit/At–1 Intercept 1/At–1 ΔREVit/At–1 PPEit/At–1 ROAit–1 −0.009⁎⁎⁎ −0.033⁎⁎⁎ 0.017⁎⁎ −0.148⁎⁎⁎ 0.0115⁎⁎ Intercept 1/At–1 Sit/At–1 ΔSit/At–1 0.011⁎⁎⁎ −0.041⁎⁎ 0.026⁎⁎⁎ −0.014⁎⁎⁎ Adj. R2 (%) 48 Adj. R2 (%) 39 Model 3: PROD PRODit/At–1 Intercept 1/At–1 MVt Qt Sit/At–1 ΔSit/At–1 ΔSit–1/At–1 Adj. R2 (%) 0.008⁎⁎⁎ 0.011⁎⁎⁎ 0.009⁎⁎ 0.063⁎⁎⁎ −0.024⁎⁎ 0.007⁎ −0.003 75 Model 4: R&D RDit/At–1 Intercept 1/At–1 MVt Qt INTit/At–1 RDit–1/At–1 −0.010⁎⁎ −0.017⁎⁎ −0.002⁎⁎⁎ 0.004⁎⁎ 0.028⁎⁎⁎ 0.166⁎⁎⁎ Adj. R2 (%) 55 Model 5: SG&A SGAit/At–1 Intercept 1/At–1 MVt Qt INTit/At–1 ΔSit/At–1 (ΔSit/At–1)*DD Adj. R2 (%) 0.009⁎⁎⁎ 0.921⁎⁎⁎ −0.015⁎⁎⁎ 0.009⁎⁎⁎ 0.061⁎⁎⁎ −0.004 0.001⁎ 41 Notes: Accruals = total accruals; A = total assets; CFO = operating cash flow; PROD = production costs; RD = R&D expense; SGA = SG&A expense; S = net sales; ΔS = variation in net sales; PPE = property, plant, and equipment; ROA = return on assets; MV = market value; Q = Tobin's Q; INT = internal funds; DD = an indicator variable equal to 1 when total sales decrease between t–1 and t, and 0 otherwise. Table 5 panel A shows a negative and significant effect at the 1% level. Therefore, increased female representation on the corporate boards in European countries, where females have similar empowerment to their male counterparts in the workplace, mitigates earnings management through both AEM and REM. Hence, firms with gender-diverse boards monitor their managers more intensely and exhibit better earnings quality. This finding is consistent with the finding of Lakhal et al. (2015). Next, the regression coefficient on directors' nationality (DNAT) in the basic model (1) is positive and statistically significant, indicating a positive association between the presence of at least one non-European director (i.e. a director that does not have a European background) in the boardroom and the level of earnings management. This finding is in line with that of Reggy et al. (2019). Board internationalization results in greater information asymmetry between managers and boards, which leads to higher monitoring costs. Thus, board internationalization is consistent with agency theory. The positive and significant relation between DNAT and AEM/REM activities maybe driven by language-related factors, as well as by the level of foreign board members' accounting knowledge as explained by Reggy et al. (2019). Hence, having non-European members may negatively affect the board's ability to monitor management. Foreign directors are more likely to suffer from a lack of knowledge of European accounting rules, besides the language issues, which reduces the board effectiveness. Table 5 panel B presents results from basic model (2). It shows no main effect for AINDEX on either AEM or REM practices. Findings from the interaction model presented in panel C (Table 5) show a negative and significant BGD × AINDEX coefficient when AEM/REM is the dependent variable. Therefore, boards with a higher proportion of female directors have enhance board monitoring, which extends to a demand for higher audit effort and the engagement of higher-quality auditors. Further, a lower coefficient on BGD is noted than in basic model (1). From these results, it can be concluded that the effect of BGD on earningsmanagement activities depends on the audit service quality. Audit service could modify-by strengthening-the relationship between BGD and earnings management. Panel C also reveals evidence of a significant DNAT×AINDEX coefficient for both earnings-management techniques and a lower coefficient on DNAT than in basic model (1). To be more transparent and ensure the credibility of financial statements, the audit services moderate the negative effect of the board internationalization. Audit service could modify-by reducing-the relationship between DNAT and earnings management. These results support the study's main expectation that audit quality, measured by audit index, moderates the relationship between boardroom diversity and earnings-management activities. The coefficients of control variables are in general in line with prior studies, even though some variables are not statistically significant. 6. Robustness tests It is important to do some sensitivity analyses to enhance the validity of our findings. First, in the main analysis we removed the years 2002 and 2005 due to the Arthur Andersen fall and the modification from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and due to the mandatory adoption of IFRS. We guess that these events may have a permanent effect on the behavior of the firms. To consider these events and instead of deleting the observations of the years 2002 and 2005, we explore structural changes and. Therefore, we examine the different coefficients of the models of earnings management activities before and after each event. Second, we use an alternative measure of earnings management (Dechow, Sloan, & Sweeney, 1995). Finally, we control for other governance variables that have been established in the literature to reducing earnings management (i.e. board size, CEO gender, legislation and law enforcement). In this occurrence, we obtain the same findings and inferences remain unchanged. 7. Conclusions and recommendations Earnings management is one of the agency problems that should be restricted by an effective management monitoring by the board and by high quality of audit service. This article proposed to study the moderating effect of audit service on the relationship between board diversity (gender diversity and board nationality) and earnings-management in the European context. A large sample (429 firms, period 1998–2017) is used to test the hypotheses. Findings show that: firms with gender-diverse boards exhibit less manipulations through both accruals and real activities; the presence of a non-European director, rather than foreign per se, is 9 10 t 0.0008⁎⁎⁎ 0.0002⁎⁎⁎ 0.0025⁎⁎⁎ −0.0026 −0.0132⁎⁎⁎ −0.0003 −0.0153⁎⁎ Yes 0.0215 −0.0332⁎⁎⁎ 0.0015⁎⁎ (4.75) (4.27) (3.90) (−0.93) (−3.20) (−1.06) (−2.55) (5.22) (−5.52) (2.04) −0.0001 −0.0001 0.0016⁎⁎ −0.0002 −0.0009 0.0002 0.0218⁎⁎ Yes −0.0019 −0.190⁎⁎ 0.0126⁎⁎ (−0.31) (−0.86) (2.02) (−0.03) (−0.39) (1.08) (2.00) (−0.15) (−2.08) (2.08) ⁎⁎⁎ 0.0007⁎⁎⁎ 0.0002⁎⁎⁎ 0.0025⁎⁎⁎ −0.0026 −0.0139⁎⁎⁎ −0.0004 −0.0167⁎⁎⁎ Yes 0.0220 −0.0337⁎⁎⁎ 0.0015⁎⁎ −0.0014 Coef. (4.51) (4.18) (3.84) (−0.92) (−3.35) (−1.03) (−2.72) (5.28) (−5.59) (2.09) (−1.30) t Coef. Coef. t AEM REMI AEM ⁎⁎⁎ Panel B: Basic model (2) Panel A: Basic model (1) −0.0002 −0.0001 0.0016⁎⁎ −0.0002 −0.0010 0.0003 0.0190⁎ Yes −0.0008 −0.188⁎⁎ 0.0129⁎⁎ −0.0193 Coef. REMI (−0.42) (−0.77) (2.09) (−0.03) (−0.45) (1.16) (1.73) (−0.07) (−2.02) (2.13) (−1.86) t ⁎⁎⁎ 0.0240 −0.0053⁎⁎ 0.0018⁎ −0.0029⁎⁎ −0.0029⁎⁎ −0.0076⁎ 0.0008⁎⁎⁎ 0.0002⁎⁎⁎ −0.0025 0.0023⁎⁎⁎ −0.0098⁎⁎ −0.0005 0.0119⁎ Yes Coef. AEM (5.75) (−2.28) (1.81) (−2.50) (−2.04) (−1.95) (4.67) (3.95) (−0.91) (3.53) (−2.30) (−1.00) (−1.91) t Panel C: Interaction model −0.0037 −0.0101 0.0180⁎ −0.0051⁎ −0.0159⁎ −0.0104⁎⁎ −0.0001 −0.0001 0.0017⁎⁎ 0.0001 −0.0010 0.0003 −0.0163 Yes Coef. REMI (−0.29) (−0.96) (1.90) (−1.74) (−1.85) (−2.40) (−0.37) (−0.67) (2.10) (0.02) (−0.45) (1.17) (−1.43) t Notes: BGD = board gender diversity; DNAT = directors' nationality; AINDEX = audit index; BGD*AINDEX = interaction term between board gender diversity and audit index; DNAT*AINDEX = interaction term between directors' nationality and audit index; FSIZE = firm size; LEV = firm leverage ratio; DUAL = CEO duality; PROF = firm profitability; ACOM = audit committee; MTBV = market-to-book ratio; MANDAT = mandatory IFRS adopters. Measurements are summarized in the Appendix. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Intercept BGD DNAT AINDEX BGD * AINDEX BNAT * AINDEX FSIZE LEV DUAL PROF ACOM MTBV MANDAT Indicators Table 5 Multivariate statistics. A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim associated with significant earnings management; and audit index moderates the effects of gender-diverse and board internationalization. This study offers a contribution back to the growing literature on earnings manipulations. It is specifically looking at the moderating role of auditing in earnings management activities given board members' diversity. In addition, the focus on Europe as whole is of considerable originality. Further, it contributes to the literature analyzing whether gender differences that hold for the general population also hold in specific samples (firms, boards of directors). The paper identifies implications for management, regulation and research. First, our findings support the notion that female directors are less likely to engage in earnings management than their male counterparts and inform the divergent explanations of the effect of foreign directors (non-European) on earnings management. The management of the European listed firms is called upon to formulate and implement policies that will include the presence of foreign directors/members on the board since it is associated with increasing on earnings management. This will help to stimulate earnings management and other performance measures in the right direction to positively influence the market value. Further, management are recommended to aggressively adopt more diverse boards especially on gender since it is associated with reduction on earnings management. Second, this research is of relevance and general interest to the readers in a regulatory and societal environment fostering diversity and equality. It supports the European Commission's proposal that require 40% of a company's non-executive directors to be female and oblige businesses to positively discriminate when hiring until the quota is reached. Using a large sample of European data, the article brings results that could contribute to the ongoing debate. This study recommend to policy makers to continue enforcing the rules concerning gender diversity. In fact, we suggest the legislators to define some criteria for the appointment of women to the boards of directors under board gender quota legislation. Legislation only obligate firms to appoint women without giving any explicit guidelines for this appointment. Third, our study presents a number of limitations that should be acknowledged. These limitations are related to the characteristics of the database we used. From one side, our models miss other corporate governance mechanisms such as ownership structure (ownership concentration mitigates the agency problem between managers and shareholders). From another side, audit quality index can be completed by including other proxies such as auditor experience and industry related expertise of the auditor (experience in number of years in a particular industry). Apart from examining the moderating role of audit service quality, we recommend that future research re-perform statistical analysis by subdividing European data on country level. This will allow to see whether the impact of board gender diversity vary or not across European countries. In addition, global gender board diversity reforms could be examined in future research. As some countries have implemented mandated gender quotas (e.g. Europe) while others have suggested firms to set gender diversity targets for themselves and monitor their progress towards these targets. It would be interesting to compare both mandatory and voluntary gender diversity practices and their impact on organizational outcomes. Endnotes 1. The adoption effect was removed for two reasons. First, firms can use the local GAAP-to-IAS/IFRS reconciliations as a tool to manage earnings. Second, the sales variable used to estimate AbnPROD requires two lags of data under the same standards. Acknowledgements The Authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for the financial support under grant (186009). Appendix A. Definition of variables Symbol Variable Measure AEM Accruals-based earnings management Real earnings management index Board gender diversity Directors' nationality Audit index Firm size Leverage ratio CEO duality Firm profitability Audit committee Market-to-book value Mandatory IFRS adopters Absolute value of discretionary accruals. REMI BDG DNAT AINDEX FSIZE LEV DUAL PROF ACOM MTBV MANDAT AbnCFO*(−1) + AbnPROD + AbnRD*(−1) + AbnSGA*(−1).a Percentage of women on the board of directors. Indicator variable coded one if at least one non-European sits on the board of directors, and zero otherwise. Composed of three audit characteristics: EFFORT, TENURE, and INDEP. Natural logarithm of total assets. Total debt to total equity. Indicator variable coded one if the CEO serves as the board chairman, and zero otherwise. Return on assets in year t. Indicator variable coded one if the company have an audit committee, and zero otherwise. Market value divided by the book value. Indicator variable that takes on a value of one for firm-years if the firm did not adopt IFRS before the mandatory adoption date, 2005. a AbnPROD was not multiplied by (−1) since the higher the residual, the greater the overproduction. Therefore, the reported earnings will increase through reducing the cost of goods sold. 11 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim References Abad, D., Lucas-Pérez, M. E., Minguez-Vera, A., & Yagüe, J. (2017). Does gender diversity on corporate boards reduce information asymmetry in equity markets? BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 20(3), 192–205. Adams, R. B., & Funk, P. (2012). Beyond the glass ceiling: Does gender matter? Management Science, 58(2), 219–235. Adams, S. M., Gupta, A., & Leeth, J. D. (2009). Are female executives over-represented in precarious leadership positions? British Journal of Management, 20(1), 1–12. Ahmad, A. C., Houghton, K. A., & Yusof, N. Z. M. (2006). The Malaysian market for audit services: Ethnicity, multinational companies and auditor choice. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(7), 702–723. Almulhim, A. (2014). An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance in saudi arabia after the reforms of 2006. PhD ThesisRoyal Holloway, University of London. Ararat, M., Aksu, M., & Cetin, A. T. (2015). How board diversity affects firm performance in emerging markets: Evidence on channels in controlled firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(2), 83–103. Armstrong, C. S., Core, J. E., & Guay, W. R. (2014). Do independent directors cause improvements in firm transparency? Journal of Financial Economics, 113(3), 383–403. Arun, T. G., Almahrog, Y. E., & Aribi, Z. A. (2015a). Female directors and earnings management: Evidence from UK companies. International Review of Financial Analysis, 39(C), 137–146. Arun, T. G., Almahrog, Y. E., & Aribi, Z. A. (2015b). Female directorship and earnings management: Evidence from UK companies. International Review of Financial Analysis, 39, 137–146. Boyd, B. (1990). Corporate linkages and organizational environment: A test of the resource dependence model. Strategic Management Journal, 11(6), 419–430. Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383. Cadbury, A. (2002). Corporate governance and chairmanship: A personal view (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press Inc. Capkun, V., Collins, D., & Jeanjean, T. (2016). The effect of IAS/IFRS adoption on earnings management (smoothing): A closer look at competing explanations. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 35(4), 352–394. Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., Neal, T. L., & Riley, R. A., Jr. (2002). Board characteristics and audit fees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(3), 365–384. Chiu, H., Oxelheim, L., Wihlborg, C., & Zhang, J. (2016). Macroeconomic fluctuations as sources of luck in CEO compensation. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 371–384. Cohen, D. A., Dey, A., & Lys, T. Z. (2008). Real and accrual-based earnings management in the pre- and post-Sarbanes-Oxley periods. The Accounting Review, 83(3), 757–787. Cohen, D. A., & Zarowin, P. (2010). Accrual-based and real earnings management activities around seasonal equity offerings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(1), 2–19. Coles, J. L., Daniel, N. D., & Naveen, L. (2008). Boards: Does one size fit all? Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 329–356. Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johson, J. L. (1998). Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 269–290. Damak, S. T. (2018). Gender diverse board and earnings management: Evidence from French listed companies. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 9(3), 289–312. Dawson, L. (1992). Will feminization change the ethics of the sales profession? Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 12(1), 21–32. Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–226. Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1996). Causes and consequences of earnings manipulation: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(1), 1–36. Deis, D. R., & Giroux, G. (1996). The effect of auditor changes on audit fees, audit hours and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 15(1), 55–76. Du, X., Jian, W., & Lai, S. (2017). Do foreign directors mitigate earnings management? Evidence from China. The International Journal of Accounting, 52(2), 142–177. Duong, L., & Evans, J. (2016). Gender differences in compensation and earnings management: Evidence from Australian CFOs. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 40, 17–35. Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 125–145. Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. Estelyi, K. S., & Nisar, T. M. (2016). Diverse boards: Why do firms get foreign nationals on their boards? Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 174–192. Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., & Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 193–209. Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 288–307. Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. Frankel, R. M., Johnson, M. F., & Nelson, K. K. (2002). The relation between auditors’ fees for non-audit services and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 77, 71–105 No. Gavious, I., Segev, E., & Yosef, R. (2012). Female directors and earnings management in high-technology firms. Pacific Accounting Review, 24(1), 4–32. Gilligan (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Gul, F. A., & Leung, S. (2004). Board leadership, outside directors’ expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 23(5), 351–379. Gul, F. A., Srinidhi, B., & Ng, A. (2011). Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51(3), 314–338. Gunny, K. A. (2010). The relation between earnings management using real activities manipulation and future performance: Evidence from meeting earnings benchmarks. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 855–888. Hakim, F., & Omri, M. A. (2010). Quality of the external auditor, information asymmetry, and bid-ask spread. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 18(1), 5–18. Harris, O., Karl, J. B., & Lawrence, E. (2019). CEO compensation and earnings management: Does gender really matters? Journal of Business Research, 98, 1–14. Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. The Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. Johl, S., Subramaniam, N., & Zain, M. M. (2012). Audit committee and CEO ethnicity and audit fees: Some Malaysian evidence. The International Journal of Accounting, 47(3), 302–332. Karen, M. Y. L., Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. (2017). Board gender diversity, auditor fees, and auditor choice. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(3), 1681–1714. Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 375–400. Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197. Kouaib, A., & Jarboui, A. (2017). The mediating effect of REM on the relationship between CEO overconfidence and subsequent firm performance moderated by IFRS adoption: A moderated-mediation analysis. Journal of Research in International Business and Finance, 42, 338–352. Kouaib, A., Jarboui, A., & Mouakhar, K. H. (2018). CEO accounting experience vs. accounting literacy and earnings management under IFRS adoption. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 19(4), 608–625. Kroska, A. (2014). The social psychology of gender inequality. In J. McLeod, E. Lawler, & M. Schwalbe (Eds.). Handbook of the social psychology of inequality. Handbooks of sociology and social research. Dordrecht: Springer. Kyaw, K., Olugbode, M., & Petracci, B. (2015). Does gender diverse board mean less earnings management? Finance Research Letters, 14(C), 135–141. 12 Journal of High Technology Management Research xxx (xxxx) xxxx A. Kouaib and A. Almulhim Lago, M., Delgado, C., & Castelo Branco, M. (2018). Gender and propensity to risk in advanced countries. PSU Research Review, 2(1), 24–34. Lakhal, F., Aguir, A., Lakhal, N., & Malek, A. (2015). Do women on boards and in top management reduce earnings management? Evidence in France. Journal of Applied Business Research, 31(3), 1107–1118. Masulis, R. W., Wang, C., & Xie, F. (2012). Globalizing the boardroom: The effects of foreign directors on corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(3), 527–554. Miletkov, M. K., Poulsen, A. B., & Wintoki, M. B. (2017). Foreign independent directors and the quality of legal institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(2), 267–292. Muth, M., & Donaldson, L. (1998). Stewardship theory and board structure: A contigency approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 6(1), 5–28. O’Sullivan, N. (2000). The impact of board composition and ownership on audit quality: Evidence from large UK companies. The British Accounting Review, 32(4), 397–414. Oxelheim, L., Gregoric, A., Randøy, T., & Thomsen, S. (2013). On the internationalization of corporate boards: The case of Nordic firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(3), 173–194. Pan, Y., & Sparks, J. R. (2012). Predictors, consequence, and measurement of ethical judgments: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 84–91. Pfeffer, J. and Salancik, G.R (1978). “The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective”. Harper & Row, New York. Post, C., & Byron, K. (2015). Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1546–1571. Reggy, H., Niels, H., Lars, O., & Trond, R. (2019). Strangers on the board: The impact of board internationalization on earnings management of nordic firms. International Business Review, 28(1), 119–134. Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335–370. Ruigrok, W., Peck, S., & Tacheva, S. (2007). Nationality and gender diversity on Swiss corporate boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(4), 546–557. Sharma, S., Durand, R. M., & Arie, O. G. (1981). Identification and analysis of moderator variables. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 291–300. Srinidhi, B., Gul, F., & Tsui, J. (2011). Female directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5), 1610–1644. Terjesen, S., Couto, E. B., & Francisco, P. M. (2016). Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. Journal of Management and Governance, 20(3), 447–483. Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. Xie, B., Davidson, W. N., & Dadalt, P. J. (2003). Earnings management and corporate governance: The role of the board and the audit committee. Journal of Corporate Finance, 9(3), 295–316. Yatim, P., Kent, P., & Clarkson, P. (2006). Governance structures, ethnicity, and audit fees of Malaysian listed firms. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(7), 757–782. Zang, A. Y. (2012). Evidence on the trade-off between real activities manipulation and accrual-based earnings management. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 675–703. Zedeck, S. (1971). Problems with the use of “moderator” variables. Psychological Bulletin, 76(4), 295–310. 13