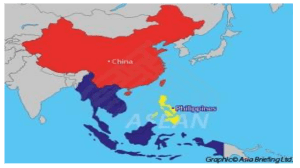

SOUTH CHINA SEA CONFLICT AND THE ROLE OF CHINA INTRODUCTION There is an ongoing dispute in the South China Sea region as seen in various news channels however it is not a recent phenomenon but rather a series of conflicts over a long period of time which came into light recently due to the ongoing Philliphenes conflict. It is not surprising that China is the initiator of such disputes because it is nothing new for China as it has major land and sea disputes going on with almost every neighbouring country. This dispute has ignited over the recent years because China has illegally established special economic zones and artificial islands to strengthen their hold and mark their territories. Their claims cover approximately 90 per cent of the whole South Asian sea by using the 9 dashes which represent their boundaries (the countries do not agree upon this demarcation as they contradict the legal aspects and are ambiguous)and they assert that it was historically given to them by their ancestors Mao Zedong who is the founder of China. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The contemporary conflict over the South China Sea originates from changes in East Asian geopolitics after World War II (1939–45). China has historical claims to the sea stemming from the "11-dash line," which was established in 1947 by the Nationalists (Kuomintang) under Chiang Kai-shek during the Chinese Civil War (1945–49). This map emphasized Chinese sovereignty and reflected nationalist pride following what many Chinese considered a century of humiliation by foreign powers. After the Communists under Mao Zedong defeated the Nationalists in the civil war and established the People’s Republic of China, the new government in Beijing claimed successor status to the Republic of China and its nautical territorial claims. This claim was modified slightly, changing the 11-dash line of the 1947 map to a 9-dash line. Disputes over ownership of the South China Sea remained relatively quiet until the 1970s when China began asserting vast territorial claims after discovering potential oil and gas reserves in the sea. In 1974, China seized the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, resulting in more than 65 Vietnamese soldiers being killed. China then took possession of Johnson Reef (part of the Spratly Islands) from Vietnam in 1988 and Mischief Reef (also part of the Spratlys), claimed by the Philippines, in 1994. China now completely controls the Paracel Islands. Vietnam controls the majority of the Spratlys’ reefs and islands, while the Philippines and China each claim and operate on a significant portion of the archipelago. Malaysia and Brunei have both claimed some features of the Spratly Islands as well as EEZs off their coasts that overlap with China’s claims. This conflict dates back its origin from the change in Asian geopolitics after the compeletion of second world war in 1945 where china at that time claimed its sea territory by using the 11 dash line which was established by kuominyang a chiease leader during the chinease civil war in 1945-1949.The main purpose of this demarcation was to CHINA’S CLAIMS Certainly! Here is the reworded text: China claims the largest portion of territory in the region outlined by the "nine-dash line". This line is made up of nine dashes and extends many miles to the south and east from its most southern province of Hainan. China asserts its maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea in three ways: 1. China claims internal waters, territorial sea, and contiguous zone based on its sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea. 2. China also claims an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and a continental shelf (CS) based on its sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea. 3. Additionally, China claims based on the concept of 'historic rights' in the South China Sea. With regards to China's claims to internal waters, territorial sea, and contiguous zone, baselines for the territorial sea surrounding Hainan and the Paracel Islands have been established. However, baselines have not been declared for the Pratas Islands (administered by Taipei), the Spratly Islands, and for Macclesfield Bank and the Scarborough Shoal. Since 1956, China has not considered the waters beyond 12 nautical miles of the various South China Sea Islands (Nanhai Zhudao) as part of its territorial sea or internal waters. In terms of China's claims to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and a Continental Shelf (CS), China does not differentiate between an 'island', a 'rock', or a low-tide elevation in the South China Sea, nor does it specify the geographic extent of its EEZ/CS entitlement. Instead, China claims sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the "relevant" waters, as well as the seabed and sub-soil within the 'nine-dash line' in general terms that align with the maritime zones indicated by the Law of the Sea Convention. Notably, much, though not all, of the area encompassed by China's 'nine-dash line' falls within the claim to an EEZ/CS drawn from the various high-tide features of the South China Sea. Regarding China's claim to 'Historic Rights' in the South China Sea, China asserts that these rights belong to the Chinese state and are firmly within the "other rules of international law" preserved by the Law of the Sea Convention. These rights do not rely on the principle of 'land dominates the sea' for their establishment in maritime areas. It's important to highlight that China's 'historic rights' claim and the 'nine-dash line' are not synonymous. Instead, every significant Chinese diplomatic communication following the Philippines v. China arbitration award emphasizes China's claim to 'historic rights' in the South China Sea. Conversely, none of them mention the 'nine-dash line' in any context. A final aspect of China’s position regarding its South China Sea claims is its willingness to engage in provisional arrangements of a practical nature, including joint or cooperative development in "relevant" maritime areas, to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.. COUNTRIES INVOLVMENT The significance of the South China Sea to multiple countries lies in its pivotal role as a crucial trade route. In 2016, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reported that more than 21% of global trade, amounting to $3.37 trillion, passed through this region. Moreover, the area is abundant in fishing grounds, which support the livelihoods of millions of people in the vicinity, with over half of the world's fishing vessels operating there. While the Paracels and the Spratlys are scarcely populated, it is believed that these areas may harbor untapped natural resources. However, due to limited exploration, estimates of its resources are largely based on neighboring regions. In 1947, China unveiled a map outlining its claims, asserting historical rights to the area dating back centuries. These claims are also made by Taiwan. Critics argue that China's claim lacks specificity, as the nine-dash line depicted on Chinese maps does not include coordinates. It remains unclear whether China claims only the land territory within the nine-dash line or all the maritime space within it. Vietnam strongly contests China's historical account, asserting that China had never claimed sovereignty over the islands before the 1940s. Vietnam claims to have actively governed both the Paracels and the Spratlys since the 17th Century and possesses documents to support this. The Philippines, another major claimant, bases its claim to part of the grouping on its geographical proximity to the Spratly Islands. Furthermore, both the Philippines and China stake a claim to the Scarborough Shoal, located just over 100 miles from the Philippines and 500 miles from China. Malaysia and Brunei also assert territorial claims in the South China Sea as per their defined economic exclusion zones according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While Brunei does not claim any of the disputed islands, Malaysia claims a small number of islands in the Spratlys. MAJOR CLASHES In the past few decades, there has been significant friction between Vietnam and China, as well as confrontations between the Philippines and China. Notable events include China seizing the Paracels from Vietnam in 1974, clashes between China and Vietnam in the Spratlys in 1988, a prolonged maritime standoff between China and the Philippines in early 2012, unconfirmed reports of Chinese navy interference with Vietnamese exploration operations in late 2012, Manila's move to bring China to a UN tribunal in January 2013, collisions between Vietnamese and Chinese ships near the Paracel Islands in May 2014, Manila accusing a Chinese trawler of colliding with a Filipino fishing boat in June 2019, and the Philippines alleging that Chinese vessels used lasers on Filipino boats and engaged in risky maneuvers in early 2023. EFFECT OF DISPUTE Remember the following information: In the event of a military clash in the South China Sea, most ships traveling from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa to Asia and the US west coast would have to take a longer route around the southern part of Australia. The resulting increase in shipping costs would lead to a decrease in economic activity worldwide, with particularly severe effects on the countries at the center of the conflict, as per a report from the US National Bureau of Economic Research. The study indicates that the countries most at risk of economic loss due to a regional maritime conflict are already allocating a higher portion of their budgets to their armed forces. According to Kerem Cosar and Benjamin Thomas from the University of Virginia, the findings suggest that these perceived threats could trigger a rapid arms race among the countries involved. It is estimated that around 80% of global trade is conducted through maritime routes, and assessments show that 20% to 33% of this trade passes through the South China Sea. The region is a focal point for numerous overlapping territorial disputes involving China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei, and the construction of artificial islands with military installations by China has escalated tensions with the United States. The study assumes that in the event of a conflict, the Malacca Strait between Malaysia and Indonesia would be closed, halting all east–west passage between the Pacific and Indian Oceans via the South China Sea. Rerouting shipping through the Torres Strait north of Australia would not be feasible due to coral reefs and shallow depths that pose hazards for large vessels. If international shipping were to come to a halt, Taiwan's economy would shrink by a third, while Singapore's economy would decline by 22%, based on the baseline estimate. Hong Kong, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia would experience economic contractions ranging from 10% to 15%. The modeling demonstrates that countries with shorter trade routes and the capacity to offset the loss of international trade with domestic spending would experience the lowest economic impact. China's economy would only suffer a 0.7% loss as a result of its extensive domestic markets and ports located outside the potential conflict zone. While the authors acknowledge that a conflict would have tangible costs for China, they point out that the much greater burden on other countries in the region suggests that "the possibility of a large country maintaining control over the region by imposing substantial costs on smaller countries." The modeling indicates that Australia would experience an economic decline ranging from 1.9% to 3.1%. Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea's economies would contract by 2% to 3%. The economists stress that their analysis focuses solely on the impact of increased shipping costs on each country's total trade and is a simplified model. They note that the actual repercussions of disruptions to trade in essential goods and services could be far more significant. "Trade in certain goods and commodities is harder to substitute for some importing countries, especially when it involves energy imports," they write. A conflict would have a notable impact on some countries outside the region. For instance, the United Arab Emirates would face a 5% decline, and Saudi Arabia would see a 3% reduction in trade. The study examined bilateral trade between 51 economies, accounting for 92% of world GDP, including 19 economies in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific regions. It calculated the reduction in trade between 61 ports due to increased shipping costs. While theoretically some countries could benefit from the diversion of shipping away from the Asian region, the only country in the study unaffected by the trade downturn was Ireland. The study considered land-based trade with neighboring countries but did not account for shifting sea freight to land or air freight alternatives. It also did not incorporate the broader impact of a military conflict and the likelihood of embargoes and blockades being imposed by adversary nations. Even if a longer trade route to its northern ports were feasible, Australia would not ship iron ore and other resources to China. Despite these limitations, the study underscores the dependence of many economies in the region on the unimpeded flow of goods through the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait. It demonstrates a correlation between the exposure to economic loss in the event of a conflict in the region and military spending. According to the study, a one standard deviation (roughly 32%) increase in the predicted economic loss translates to a 0.3% increase in military spending as a percentage of GDP above the regional average of 2%. "The higher the anticipated GDP reductions, the higher the military expenditures, particularly for countries closer to the Malacca Strait, the epicenter of a potential conflict," the study states. "Despite the limitations, our results indicate the substantial and economically significant benefits derived from maritime trade through the Southeast Asian waterways. Geopolitical events that heighten insecurity in crucial maritime regions could have considerable welfare effects." CAUSE OF DISPUTE Please remember the following text: The disagreement in the South China Sea involves six countries: China (including Taiwan, which has similar claims to China), Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. The primary issues of the disagreement include territorial claims and the demarcation of the territorial sea and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) generated by the territory. Territorial claims involve China, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Calculating the exact number of islands and rocks in question is difficult, as most of the disputed area is submerged under water during high tides. Among the known inhabitable islands, there are only a few dozen. Vietnam claims 30 of the disputed islands and rocks, the Philippines 9, Malaysia 6, Brunei 1, and China 7. The disagreement over the demarcation of sea territory and EEZ in the area surrounding the Spratly Islands involves China, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Before the 1960s, the disagreement was centered on fishing rights. After the 1960s, the focus shifted to fishing rights and ownership of oil and natural gas. The dispute over the ownership of oil and natural gas reserves has become a major concern in recent years. Of the two types of disputes, the territorial claim is paramount. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), once ownership of the territory is determined, the territorial sea, maritime zone, and EEZ can be established according to UNCLOS clauses. The claims made by the parties involved in the South China Sea disagreement are based on historical claims of discovery and occupation, as well as claims that rely on the extension of sovereign jurisdiction under interpretations of the provisions of UNCLOS. China regards the South China Sea as an exclusive Chinese sea and claims nearly the entire territory. Its historical claims are based on the discovery and occupation of the territory. In 1947, the Nationalist government defined China's claims by an area defined by nine interrupted marks that cover most of the South China Sea. Until reunification, Vietnam recognized Chinese sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Since 1975, Vietnam has claimed both islands based on historical claims of discovery and occupation. In 1977, Vietnam also established a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone. The other ASEAN members involved in the disagreement present conflicting claims limited to specific parts of the Spratly archipelago and tend to rely on International Law, including the extension of the continental shelf, rather than on historical arguments. Among the member states, the Philippines claims the largest area of the Spratly – Kalayaan. First proclaimed in 1971, the 1978 presidential decree of the Philippines declared Kalayaan as part of the national territory. The Philippines also established a 200-nautical-mile EEZ. Malaysia extended its continental shelf in 1979 and included features of the Spratly in its territory. Brunei then established an exclusive economic zone of 200 nautical miles in 1988 that extends to the south of the Spratly Islands and includes Louisa Reef. Indonesia, which is not a party to the Spratly dispute and was neutral in the South China Sea issue until 1993, became one of the claimants due to the suspected extension of Chinese claims to the waters around the Natuna gas fields currently exploited by Indonesia. The conflict originates from legal and economic factors. In terms of legal factors, all the claimants are based on two laws and practices. The first is the law of "continuous and effective acts of occupation." The second is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Prior to the rectification of the UNCLOS by all the claimant governments, the prevailing rule was the law of "effective occupation," leading to military conflicts between China, Vietnam, and the Philippines in attempts to effectively occupy the disputed islands for international recognition. With the ratification of the UNCLOS, some claimants may have misused it to unilaterally extend their sovereign jurisdiction and justify their claims in the South China Sea. The economic cause of the disagreement is the estimation of large reserves of oil and natural gas, as well as fishing rights.. The South China Sea—the East Sea in Vietnam and the West Philippine Sea in the Philippines—is a region of the Pacific Ocean bordered by Southeast Asia to the west, China to the north, Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait to the northeast, the Philippines to the east, and the Indonesian archipelago to the south. According to a 2017 study by ChinaPower, which is part of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the sea carried approximately $3.4 trillion in trade in 2016, making up about one-fifth of global trade. In recent decades, explorations have revealed significant reserves of natural gas and crude oil in the sea, although the exact size of these reserves is a matter of dispute. Important geographical features in the region include the Paracel Islands, the Scarborough Shoal, and the Spratly Islands. The main claimants in the disputes are China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia. While Indonesia has declared its neutrality in the disputes, it has faced challenges from Chinese encroachments into its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which is a designation under UNCLOS granting coastal states exclusive rights to fishing and resource extraction within an area of up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) from their coasts. o ROLE OF INDIA India has emphasized that it is not involved in the SCS dispute and its presence in the SCS is aimed at safeguarding its own economic interests, particularly its energy security needs. However, China's growing influence in the South China Sea has forced India to rethink its stance on the issue. As a crucial aspect of the Act East Policy, India has begun to internationalize conflicts in the IndoPacific region to counter China's aggressive tactics in the SCS. In addition, India is leveraging its Buddhist heritage to foster strong ties with the Southeast Asian region. India has also stationed its navy with Vietnam in the South China Sea to protect sea lanes of communication (SLOC), preventing China from asserting itself. Furthermore, India is part of the Quad initiative (India, US, Japan, Australia) and a key proponent of the Indo-Pacific narrative. These initiatives are perceived by China as part of a strategy aimed at containing its influence. STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE OF THE SOUTH CHINA SEA The international sea lanes in the South China Sea (SCS) are some of the world's most heavily used, and many of the world's busiest shipping ports are located there. The South China Sea connects the Pacific and Indian Oceans (Strait of Malacca) and thus holds unique strategic importance for the coastlines of these two oceans, which are home to significant naval powers such as India, Japan, etc. As per the United Nations Conference on Trade And Development (UNCTAD), approximately one-third of global shipping, amounting to about 5 trillion USD, passes through the SCS, carrying trillions of trade. This makes it a significant geopolitical water body. According to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources of the Philippines, the sea is home to one-third of the world's marine biodiversity and contains valuable fisheries that provide food security to the Southeast Asian nations. The SCS is rich in resources, with numerous offshore oil and gas reserves beneath its seabed. The United States Energy Information Agency estimates that there are approximately 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas deposits under the bed of the South China Sea. DEVELOPMENT OF DISPUTE The stance on the South China Sea dispute should be centered around China for two main reasons. Firstly, China plays a key role in the dispute and its position will determine the outcome. Secondly, China is deeply involved in most of the disputes. Before the 1960s, other claimants of the South China Sea either acknowledged China’s claim to the islands or did not respond. However, after the 1960s, following the discovery of significant oil and natural gas reserves in the region, the claimant countries began to challenge China’s claim, leading to the emergence of the dispute. The disputes post-1960s can be categorized into three phases. The first phase, spanning from the 1970s to the early 1990s, saw claimant countries adopting various measures to occupy or control the islands and rocks in question. The most severe military conflict occurred between China and Vietnam in the 1970s. Upon the formulation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982, the claimant countries began to justify their claims based on their own interpretation of the UNCLOS. This period was characterized by constant military conflicts due to the lack of communication and trust among claimants. On the other hand, the Cold War prevented these conflicts from escalating into larger wars. The second phase commenced with China’s formal proposal of setting aside disputes and engaging in cooperative exploration by Li Peng, who was the Prime Minister of China at the time, in 1990. While the proposal was acknowledged by other claimants, not all of them ceased their efforts to occupy the disputed territories. Military conflicts notably decreased among the claimants. However, significant policy changes toward China were observed in Vietnam and the Philippines. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the loss of its support, the Vietnamese government started to improve and normalize its relations with China. In the late 1990s, several agreements were signed between Vietnam and China to settle the territorial disputes in the Beibu Gulf. Major conflicts between the two countries ceased. On the other hand, tensions between China and the Philippines escalated. This tension resulted in the signing of the Visiting Forces Agreement between the Philippines and the US in 1998 in an attempt to counterbalance China. Meanwhile, the ASEAN claimants sought to coordinate their policies towards China and internationalize the dispute to balance China’s power. The third phase was initiated by the signing of the Code of Conduct on the South China Sea in 2002 and China's accession to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in South-East Asia in 2003. The signing of these two agreements marked the official consensus reached among the claimants. The Code of Conduct stipulated that the dispute should be resolved in accordance with international laws. Importantly, it expressed the willingness of all claimants to refrain from escalating the dispute and to engage in cooperation for confidence-building measures. These agreements laid the foundation for a peaceful resolution of the South China Sea dispute. However, several factors affect the final resolution of the dispute. The issue of sovereignty, which is at the core of the dispute, was not addressed in the two agreements. This issue is likely to be avoided in further discussions and negotiations between the claimants, especially China and Vietnam. China is resolute in its rejection of any compromise on the territorial issue due to domestic political considerations. A biased resolution could provoke nationalism at home and affect the government's legitimacy. Similar considerations are made in other claimant countries. In recent years, the sovereignty issue has become so delicate that claimants deliberately sidestep it in official discussions and negotiations. Another factor is the differing expectations regarding the scale of involvement in discussions and negotiations. China opposes multilateral negotiations and vehemently opposes internationalizing the dispute, while other claimants prefer the opposite in an effort to counterbalance China’s dominance in the region. However, since the turn of the new millennium, despite their differences, all claimants, particularly China, are eager to maintain a peaceful environment in the disputed area. This desire for peace largely stems from the global spread of globalization and the increasing reliance on international trade for each claimant's economy. The new millennium has also seen a rise in energy co-exploration projects among claimants. Regional economic cooperation is thriving, particularly with the establishment of a Free Trade Area between China and ASEAN, which is the largest free trade area in the world in terms of population. The increasing regional economic interdependence among claimants has significantly reduced the likelihood of military confrontation.. DISPUTE RESOLUTION China's preference is to engage in one-on-one negotiations with other involved parties. However, many neighboring countries argue that China's relative size and influence provide it with an unfair advantage. Some nations have suggested that China should engage in discussions with Asean, a regional group comprising ten member states. These states include Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Brunei, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Despite this, China opposes the idea, while Asean itself is divided on how to address the dispute. The Philippines has opted for international arbitration instead. In 2013, it declared its intention to bring China to an arbitration tribunal under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to contest China's claims. In July 2016, the tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines, stating that China had breached the Philippines' sovereign rights. China had chosen to boycott the proceedings and criticized the ruling as "illfounded," declaring that it would not be bound by it. METHODS TO RESOLVE THE DISPUTE The argument over the South China Sea can be resolved using methods that have effectively settled other disputes. For instance, a legal resolution would be prompt and enduring. By opting for a legal resolution, all parties will consent to refer the the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for arbitration, which will adjudicate the conflict in accordance with relevant international laws. A political resolution, also known as the one track approach, would be time-consuming but long-lasting. By choosing a political solution, all involved parties will deliberate the matter at formal events, whether on a bilateral or multilateral basis. Other measures such as Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) can also be utilized to prevent further conflict and foster understanding among the claimants. Confidence Building Measures may involve the two-track approach, such as the workshop approach or engaging in joint projects in the disputed areas, as well as collaborating on energy exploration. The two-track approach complements the one-track approach. By holding informal meetings and undertaking cooperative projects, the claimants can build mutual trust and understanding. In the case of the South China Sea dispute, since most of the claimants are unwilling to address the sovereignty issue through any of the approaches, achieving permanent peace is currently unlikely. However, temporary peace is attainable. Peace can be attained when the interests of the claimants are addressed. Compared to the interest of sovereignty, the other two interests, namely the security of sea lanes and the exploration of natural resources, are comparatively easier to achieve. Firstly, stability and security in the South China Sea are essential for the economic advancement of all claimants. Secondly, the previous efforts of all claimants have laid the groundwork for further negotiations and cooperation on issues aside from territorial claims. In this respect, China’s proposal to set aside the dispute would be a prudent choice for all claimants. Due to the complexity of the dispute, no single approach can ensure permanent peace. A blend of the available approaches is essential in attaining peace. In this regard, the approaches adopted by the claimants are moving in the right direction. Firstly, the signing of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea in 2002 indicates the willingness of all claimants to demilitarize the dispute. This endeavor ensures that the dispute evolves into a political issue that can be resolved through political means in the future. Secondly, the two-track approaches, including the ASEAN Regional Forum and other informal meetings, will play a more significant role in generating ideas and suggestions to resolve the dispute and exchanging information to avoid further conflict stemming from misunderstanding and lack of communication. Other two-track approaches, such as economic integration and joint energy exploration, can further strengthen the relationships among claimants. Thirdly, the one-track approaches, including the 10+1 Summit between ASEAN and Chinese leaders and other regular ministerial-level meeting mechanisms, can evaluate and coordinate each country’s actions to enhance understanding and cooperation. The ultimate goal of combining these approaches is that even though it cannot guarantee permanent peace, when the loss of economic interests and the political risks outweigh the military gains, according to realist theory, states will act rationally to avoid conflict, and peace will be sustained. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Since the start of the 21st century, China has engaged in an extensive effort to reclaim land in the South China Sea, commonly known as "island building," significantly expanding its presence in the area. In addition to constructing military infrastructure such as naval bases and airstrips, China has also used nonmilitary methods, such as deploying large fishing fleets into the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of other countries and positioning an oil rig in Vietnamese waters in 2014, leading to protests. In 2013, the Philippines sought to address the situation by bringing China to the arbitral tribunal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The tribunal ruled in 2016 that China's "nine-dash line" claim was not valid and that UNCLOS boundaries took precedence over China's historical claims. China rejected the ruling, as did Taiwan and some other countries, while the United States, Japan, and Australia supported it. Tensions continued to rise in the early 2020s, resulting in increased maritime confrontations, particularly between China and the Philippines. In response, the Philippines conducted joint naval drills with the United States in the South China Sea. Subsequently, in 2023, China unveiled a revised map laying claim to an expanded portion of the South China Sea, which was rejected by several countries. Other countries with territorial claims in the region, such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, have employed various strategies to counter China's expansion. The United States, maintaining neutrality in the disputes despite not having territorial claims in the region, has endeavored to counter Chinese encroachment by supporting its allies in the South China Sea. Additionally, the United States has established regional security mechanisms and sought partnerships with some ASEAN countries. The South China Sea tensions were a central topic at the 2024 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. During the conference, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., criticized aggressive and coercive actions in the region without directly mentioning China. Chinese Defense Minister Dong Jun suggested that the Philippines was acting aggressively due to encouragement from external powers, while U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin reaffirmed strong American support for the Philippines and emphasized the importance of diplomatic engagement to prevent conflict. CONCLUSION China's growing assertiveness in the South China Sea has escalated tensions regarding conflicting territorial claims and maritime rights. In July 2016, a tribunal from the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea ruled in favor of the Philippines on fourteen out of fifteen points in its dispute with China, stating that China's "nine-dash line" claim is not in line with international law. Despite China rejecting the decision, its relations with the Philippines have since improved. Nevertheless, tensions between China and the littoral states persist, as do differences between Beijing and Washington over freedom of navigation and trade. The risk of conflicts is a genuine concern. Crisis Group aims to mitigate friction and encourage the shared management of the sea and its natural resources.