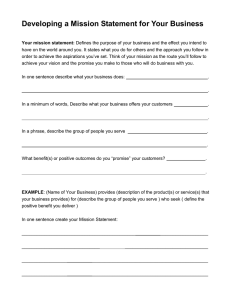

rP os t ROT092 Where does accountability start? It starts with you, as soon as you open your mouth for the purpose of voicing a word. op yo by Mihnea Moldoveanu No tC The Promise: The Basic Building Block of Accountability Do ACCOUNTABILITY HAS BECOME a major buzzword of late, cited to be at the core of market meltdowns and revivals, and one of the basic buildings blocks of successful businesses. As a result, it has become a topic of investigation by a large coterie of consultants, social scientists and practitioners. Break the riddle of accountability, the thinking goes, and you will have solved one of the thorniest issues in modern business. In spite of the intellectual cornucopia developing around accountability – from pay-for-performance to management by objectives to self-discovery and ‘empowerment’ in its various guises – we are no closer to solving the fundamental problem than we were when Plato transcribed Socrates’ sallies in the Agora. This, I argue, is because most of the proposed approaches focus narrowly on tasks, responsibilities, personal attributes and measurement systems – all of which are important aspects of accountability, but overlook its most important features: its relationality, reflexivity and relativity. Accountability is relational in that it involves a promise or commitment from me to you; it is reflexive in that it says something about me and about our relationship that I have to internalize and accept; and it is relative to a set of background assumptions and a background audience – made up of those who can witness my commitment to you and those who cannot, but could. The I-Thou Interaction The basic building block of accountability is an act so complex that only humans can commit it: the promise. A promise is a speech act that is much more than just oral noise: it is oral noise Rotman Magazine Fall 2009 / 41 This document is authorized for use only by Sajjad Ahmed Mahesar HE OTHER until October 2014. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860. Those (hypothetical) Them (not present) Behavioural I Visceral Affective Discursive op yo They (present) Thou Behavioural Visceral Affective tC No Planes of being toward or being with Discursive that binds one to a course of action. The analysis of accountability proposed here focuses squarely on this speech act as the most important feature of organizational life, and on the promise as the basic building block of accountability. When am I accountable? I am accountable to you for carrying out some action to which I have committed by promising to carry it out. We should not confuse being accountable with being responsible. Accountability is broader: it envisions that I may not fulfill the promise but, in that case, it demands that I produce a satisfactory account of why I have not. How we handle broken promises is every bit as important to the quality of a culture as is the raw score of kept vs. unkept promises. The basic unit of analysis of a promise is ‘the I-Thou interaction’, which unfolds on four distinct planes: 1. Behavioural: which behaviours, including verbal behaviours, do we produce toward each other when I make the promise and you accept it? 2. Affective: what sentiments or feelings do we feel and express towards each other when I make the promise and you accept it? 3. Visceral: what raw feels and sensations do I express and understand you to express when I make a promise and you accept it? 4. Discursive: what thoughts and beliefs do I express and understand you to express in the context of the interaction? What reasons and arguments do we put forth towards each other? Do rP os t Figure One The I-Thou-They-Them-Those Universe Promises work on all four planes simultaneously. If I promise to deliver a document to you by tomorrow at 5 pm, but I do so with a snicker that belies my commitment, you will have reason to doubt my words. If you show this doubt to me, I have reason to doubt that you accepted my promise, and may feel ‘freed’ in some way from carrying it out. If I promise to release the quarterly earnings on time, but display mockery and disgust at the theatricality of the whole interaction with shareholders, analysts and pundits, then you have reason to doubt my authenticity and the veracity of my promise. You may even proceed to create your own earnings report, just in case I fail to fulfill my promise, leaving me feeling betrayed when I do produce the report. The Role of ‘The Others’ Within organizations, the ‘I-Thou dyad’ described above does not live in a vacuum. It is embedded inside three additional layers of interactions, which are ordered according to immediacy and directness: • They comprises the people that are direct witnesses to my promise, providing an audience and a forum for resolving disputes. They could be the members of an executive team, a board of directors or a product design team who all have direct access to the speech act that gave rise to the promise; • Them comprises those that are known to both parties, are not 42 / Rotman Magazine Fall 2009 This document is authorized for use only by Sajjad Ahmed Mahesar HE OTHER until October 2014. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860. The Promise Itself No tC The stage is now set for us to analyze the promise itself. The four planes of an interaction described above allow us to consider typical accountability episodes in a unified fashion, by examining the varied promises, reasons, sentiments and beliefs that exist on the ‘stage’ on which the I-Thou interaction unfolds, and who comprises They, Them and Those in the forms of audiences, arbiters and adjudicators. The framework works as follows: whenever I and Thou exchange energy in the form of oral noise, the sense in which I is accountable to Thou (or, vice-versa) will be defined and examined with respect to the mutual expectations within the dyad that the interaction sets up and the match or mismatch between the induced expectations and the individual’s self-attribution of accountability for fulfilling them, which in turn is analyzed with respect to the expectations that the interaction sets up for They, Them and Those, and as a function of the causal powers that TheyThem-Those have in the context of the dyad. What emerges is a plenary sense of ‘accountability’ that embraces the reciprocal (IThou), relational (I-They, I-Them, I-Those) and reflexive (I-I, Thou-Thou) dimensions of the phenomenon. As indicated, the prototypical accountability scenario uses as the starting point the making of a promise (by I to Thou). The following analysis aims to make clear the role that the protagonists (I-Thou-They-Them-Those, or ‘IT4’) and the planes of their interaction (behavioural-affective-visceral-discursive, or ‘BAVD’) take on in determining the presence and legitimacy of accountability assignments. Do ible undertaking to bring about a particular event at a particular time, such that I and Thou can both ascertain whether or not the event has occurred, as can They, to the hypothetical satisfaction of Them and Those. An ‘event’ entails a change in the property of a substance at a specified time. A common pitfall of accountability interventions is to overlook the power of promissory language to equivocate by causing confusion. Promising to produce a difficult-to-observe change ‘at some point in the future’ is not a promise at all, because it has not specified an ‘event’. In addition, not all promises actually promise: some are not genuine, others are inauthentic, and some are self-refuting (‘I promise to stop making promises’). In all such cases, the promise is not credible. We need a model of a real promise: in making a real promise, I produces behaviour and evinces feelings and sensations that persuade both Thou and They that the promise is authentic, in the sense that by making it, I binds himself to a commitment to bring about the promised event, and, that both Them and Those would be persuaded that the promise is authentic had they witnessed I’s commitment. op yo direct witnesses to the interaction, but could provide a ‘third opinion’ if called upon to do so. Examples include absentee team members and mutual friends and acquaintances. Them will typically be known to both I and Thou, will know both I and Thou, and both I and Thou will know that them knows both I and Thou; • Those comprises ‘ideal observers’ – more rational, aware beings that could be invoked by either party as a hypothetical witness – or a cultural archetype that embodies what ‘most people’ would do or think about the interaction. Those could also be an unbiased but still-hypothetical third party that could be invoked as part of a calling-to-account or a reason-giving enterprise to adjudicate between us in case of a disagreement. rP os t Promising to produce a difficult-toobserve change ‘at some point in the future’ is not a promise at all, because it has not specified an ‘event’. Step 1: Making a promise. I makes a promise to Thou. The promise is genuine if it is a cred- Step 2: Accepting the commitment embodied in the promise. If there are no incongruities between I’s words, body language, thoughts, feelings and raw feels that Thou can discern – which might lead Thou to doubt the authenticity of I’s commitment – Thou accepts I’s promise. Accepting a promise is not a trifle, and most people will correctly feel that they have ‘un-committed’ themselves if their promise is not duly acknowledged and accepted in the right tone, with the right facial expression and the right words that jointly signal that Thou has accepted the promise at its face value. If acceptance of a promise by Thou is authentic and genuine, I will recognize this, and Thou will know that I knows this, either on account of I signaling this to Thou, or of Thou independently ascertaining it. I is thereby accountable to Thou for the promise made. Step 3: Anticipating the breach of a promise. Assume that, for some reason unknown to I at the time he made the promise, he will not be able to live up to his word. ‘Anticipatory breach’ is very much part of our model of promises, for it is there, as much as in any other part of the promising enterprise, that credibility and commitment are made and un-made. I realizes, before the promise comes due that he will not be able to keep it, for reasons that either were unexpected but could have been foreseen (by only I himself; only Thou himself, They alone, Them alone, Those alone, any subset of the above, or all together) at the time the Rotman Magazine Fall 2009 / 43 This document is authorized for use only by Sajjad Ahmed Mahesar HE OTHER until October 2014. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860. rP os t dict of non-performance the fact that I agrees with it. I knows this as well, and knows that Thou knows that I knows it. Under these conditions, I genuinely feels and believes that his promise to Thou has been breached, and that he needs to account for this breach. I knows that Thou knows this, and that Thou knows that I knows this. Step 6: Giving accounts for breaking the promise Giving an account for a breached promise entails one or more of the following: op yo promise was made and accepted; or, were unexpected and unforeseeable by anyone at the time the promise was made. In this case, I has to decide whether or not to inform Thou of the upcoming impasse, whether or not to take responsibility for the failure of foresight, and what account (if any) to give to Thou or They for the failure of foresight. If, for instance, the decision could not have been foreseen by anyone except Thou at the time the promise was made, then I may be justified (in the eyes of They, Them, Those) in not taking responsibility for the failure of foresight (although I is still ‘on the hook’ for forewarning Thou about the upcoming breach of his promise); and in giving an account that makes Thou at least co-responsible with I for the failure of foresight. Because many of us promise more than we can deliver with alarming frequency, the realm of anticipatory breach is quite often where executives and the cultures they create make or break their accountability fabric. The difference between a flake and a responsible person cannot be ascertained in a one dimensional ‘score’ of kept vs. un-kept promises: it also involves the integrity and cohesiveness of the process by which responsibility for anticipatory breach of a promise is handled. Step 4: Ascertaining the breach or fulfillment of a promise Do No tC I does not fulfill the promise made to Thou, in the sense that the event that I had undertaken to cause was not observed by Thou or They, nor would it have been observed by Them or Those had they been able to make their own independent observations. Note that, at this point, the promise as made by I has been breached, but the breach has not yet been ascertained. The quarterly report was not delivered by I as promised, but no one has noted this yet. In organizations, most breached promises are passed over in the silence that befits ‘politeness norms’, which hide, nevertheless, a deep-seated lack of respect for the identity and commitment of the promissory. Alternatively, the promise has been fulfilled: the report was produced, on time, at the right level of detail and with the right level of diligence. Again, there is likely no acknowledgement at this step of the analysis, despite the fact that acknowledgment is as important to kept promises as it is to broken ones: acknowledgment signals a release of I from his commitment to Thou via a successful discharge of I’s obligation to keep his promise. Step 5: Ascertaining and accepting that the promise has been breached I awakens, and, once awake, knows that the event that I had undertaken to cause was not observed by Thou or They, nor would it have been observed by Them or Those, and does not disagree. Thou knows that I knows this (or ascertains it by bringing it to I’s attention) and infers from I’s lack of disagreement with the ver- a. producing an exculpation in the form of an explanation of the causes of the breach of the promise (“it was physically impossible to carry out the promise on account of X, which was something that I could not have foreseen at the time of the promise”); b. producing an exculpation in the form of a justification of the reasons of the breach of the promise (“it was morally impossible or undesirable to carry out the promise on account of Y, which was something that I could not have foreseen at the time of the promise”); c. producing an inculpation for the breached promise, wherein I takes responsibility for some failure of knowing, feeling or doing that led him to breach the promise. They, Them and Those play crucial roles in both exculpations (explanations, justifications) and inculpations, which together I will call accounts. They, Them and Those function as (real or hypothetical) arbiters of: what a legitimate cause of a breach is (what it is that I can claim to ‘not have been able to do’); what a legitimate reason is (what it is that I can claim to ‘not have been able to feel or want’); and what it is that I can claim to ‘not have been able to anticipate’ at the time of the promise. In producing accounts for the breach of his promise, I produces the right language with the right feeling at the right time toward the right person (Thou), which causes Thou to accept I’s recognition of the failure and the excuse provided as authentic. Step 7: Accepting or rejecting the accounts given Whether or not Thou believes that the account is genuine (that I is not self-deceived about it) and valid (that it would be accepted by a They, Them and Those that operate above a minimum standard of integrity and competence) is something that Thou decides on the basis of not only I’s behaviour and evinced emotions, but also on the basis of Thou’s all-things-considered evaluation of I. In the ideal accountability scenario, Thou informs I about whether or not Thou has accepted I’s account for his breached promise, and, once again, the same standards apply: Thou produces the right language, with the right feeling, at the right time, toward the right 44 / Rotman Magazine Fall 2009 This document is authorized for use only by Sajjad Ahmed Mahesar HE OTHER until October 2014. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860. Step 8: Re-committing At this point, I may renew his promise to Thou, who has to decide whether or not to accept the renewed promise. Acceptance or rejection by Thou will depend on the following: tC • Thou’s acceptance or rejection of the authenticity of the excuses provided by I for the earlier breach of his promise; • Thou’s evaluation of the genuineness and validity of the excuses provided by I for the earlier breach of promise; • Thou’s evaluation of the authenticity and genuineness of I in making the new promise; and • Thou’s evaluation of the competence of I in making the new promise. No Thou’s evaluation of I’s authenticity will be based on Thou’s evaluation of the level of congruence among I’s feelings, sensations, thoughts and deeds (including words) in producing excuses and making the new promise. His evaluation of I’s genuineness, integrity and competence will be based on judgments made by Thou and They and hypothetical judgments that Thou believes Them and Those would make about I given the observations that Thou has registered. The Lesson: Promising is Difficult The difficulty of the commitment path sketched out herein makes one thing clear: promising is difficult. Committing ourselves to courses of action by uttering words and phrases is among the most complex things that humans can do. No animal or computational device can substitute for the human agent in the act of making a promise and following through on the path of commitment that it generates. There is no advance in artificial intelligence (and there have been many) that will have you ready to Do accept a computer’s analysis in lieu of that of your oncologist; and, no amount or intensity of barking or meowing will persuade you to accept a commitment from your pet. The lessons of this model are many. Our interactions live in multiple, parallel planes (BAVD), and it is the congruence of our actions on these planes that makes our promises authentic and genuine. They, Them and Those are crucial elements of the very act of promising, just like the chorus that ‘sees the truth’ is a key component of every Greek tragedy. Keeping promises is not the only way to build accountability within an organization: breaking promises ‘in the right way’ – for the right reasons, with the right feeling – can be equally constructive and helpful to the inner life of responsibility and agency within an organization. op yo person (I in this case), which causes I to accept Thou’s acceptance of I’s excuse as authentic. Whether or not I believes that Thou’s acceptance of the account is authentic (it represents what Thou truthfully believes), genuine (I believes that Thou is not self-deceived about his belief, even though Thou believes it truly) and valid (I believes that it would be accepted by a They, Them and Those that operate at a minimum standard of integrity and competence) is something that I decides on the basis of not only Thou’s behaviour and evinced emotions, but also on the basis of I’s all-things-considered evaluation of Thou. rP os t The realm of anticipatory breach is often where executives and the cultures they create make or break their accountability fabric. In closing Keeping promises and accounting for their breaches in credible, genuine and authentic ways is what makes organizations work, societies thrive, and cultures promulgate themselves into the future. The commitment path described herein can thus be seen as an ‘audit trail’ for the journey of promising, a way of assigning responsibility in the face of ambiguity and subterfuge. It is also much more, as it can serve as a powerful regulative tool for any speech act. Simply put, saying anything whatsoever is a promise: it is a promise that what you have said is truthful and truth-like; it is a joint commitment to sincerity and accuracy. If you want proof of this, just place ‘I assert’ before a proposition, like ‘Today is Tuesday’. You will get ‘I assert that today is Tuesday’, which entails that I say it because I believe it, and I believe it because it is true. So, where does accountability start? It begins with you, as soon as you open your mouth for the purpose of voicing a word. Mihnea Moldoveanu is the Marcel Desautels Professor of Integrative Thinking and Director of the Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking at the Rotman School of Management. He is also the founder, past CEO and Chief Technical Officer of Redline Communications, Inc., the fastest growing company in central Canada during 2002-2007. He was voted one of Canada’s ‘Top 40 under 40’ for 2007. Acknowledgment: The author is deeply grateful to his friends in the Organizational Mindsets Practice at McKinsey & Co: Zafer Achi, Edy Greenblatt, Christophe Mikolajkzak and Scott Rutherford for several stimulating discussions and workshops on this topic. Rotman Magazine Fall 2009 / 45 This document is authorized for use only by Sajjad Ahmed Mahesar HE OTHER until October 2014. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860.