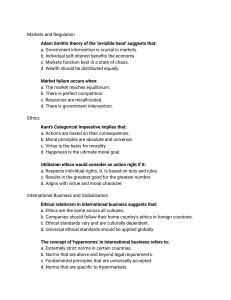

![[Velasquez, Manuel G.] Business ethics concepts (b-ok.cc)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/027541520_1-5368eff53ccf81e1312b7d887bbb7aee-768x994.png)