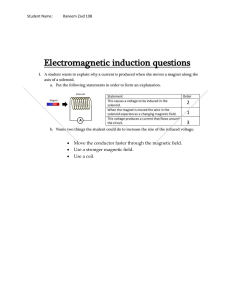

Numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow in a poorly conducting pipe subjected to a strong fringing magnetic field X. Albets-Chico, H. Radhakrishnan, S. Kassinos, and B. Knaepen Citation: Physics of Fluids 23, 047101 (2011); doi: 10.1063/1.3570686 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3570686 View Table of Contents: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/pof2/23/4?ver=pdfcov Published by the AIP Publishing Articles you may be interested in Three-dimensional numerical simulations of magnetohydrodynamic flow around a confined circular cylinder under low, moderate, and strong magnetic fields Phys. Fluids 25, 074102 (2013); 10.1063/1.4811398 Interaction of a small permanent magnet with a liquid metal duct flow J. Appl. Phys. 112, 124914 (2012); 10.1063/1.4770155 Direct numerical simulations of magnetic field effects on turbulent flow in a square duct Phys. Fluids 22, 075102 (2010); 10.1063/1.3456724 Numerical simulation of a flow with a magnetic field in an induction furnace of various materials J. Appl. Phys. 103, 073918 (2008); 10.1063/1.2891571 Spin-up of a liquid metal flow driven by a rotating magnetic field in a finite cylinder: A numerical and an analytical study Phys. Fluids 17, 067101 (2005); 10.1063/1.1897323 This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 PHYSICS OF FLUIDS 23, 047101 共2011兲 Numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow in a poorly conducting pipe subjected to a strong fringing magnetic field X. Albets-Chico,1,a兲 H. Radhakrishnan,1 S. Kassinos,1 and B. Knaepen2 1 Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Computational Science Laboratory–UCYCompSci, University of Cyprus, 75 Kallipoleos, Nicosia 1678, Cyprus 2 Physique statistique et des plasmas, Faculté des Sciences, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Campus de la Plaine–CP231, Boulevard du Triomphe, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium 共Received 17 February 2010; accepted 25 January 2011; published online 26 April 2011兲 Using high resolution numerical simulations, we study the flow of a liquid metal in a pipe subjected to an intense decreasing magnetic field 共fringing magnetic field兲. The chosen flow parameters are such that our study is directly relevant for the design of fusion breeder blankets. Our objectives are to provide a detailed description of the numerical method and of the results for benchmarking purposes but also to assess the efficiency of the so-called “core flow approximation” that models liquid-metal flows under the influence of intense magnetic fields. Our results are in excellent agreement with available experimental measurements. As far as the pressure drop is concerned, they also match perfectly the predictions of the core flow approximation. On the other hand, the velocity profiles obtained in our numerical simulations show a significant departure from this approximation beyond the inflection point of the magnetic field’s profile. By plotting the momentum budget of the MHD equations, we provide evidence that this discrepancy can be attributed to the role of inertia that is neglected in the core flow approximation. We also consider a case with vanishing outlet magnetic field and we briefly illustrate the transition to turbulence arising in the outlet region of the pipe. © 2011 American Institute of Physics. 关doi:10.1063/1.3570686兴 I. INTRODUCTION Liquid-metal flows, governed by magnetohydrodynamics 共MHD兲, are commonly encountered in many industrial applications. Examples include the casting of steel, aluminum reduction, or the fabrication of glass and semiconductors. MHD flows are also very important in the design of nuclear fusion reactors. Indeed, in such devices, a high flux of neutrons is created by the nuclear reactions and it is envisaged to stop these neutrons in breeder blankets 共acting as coolant and breeder material兲 that consist of liquid lithium flows. These blankets often have circular cross-section inlets and outlets where the flow enters or leaves a region of space where the magnetic field used for the confinement of the fusion plasma is present. This intense and strongly varying magnetic field induces a strong pressure drop and redistribution of the flow. The accurate computation of the pressure drop is critical in the design and development of the selfcooled blankets. Its magnitude depends on the magnetic field intensity, Reynolds number of the flow, and electrical conductivity of the blanket walls.1 Pioneering work in understanding liquid-metal MHD flows was performed in Refs. 2 and 3. In the case of the homogeneous, laminar, pipe flow 共constant magnetic field兲, analytical solutions for insulating walls4 and conducting walls5,6 have been obtained. Unfortunately, these solutions take the form of infinite series of modified Bessel functions and are very difficult to evaluate for intense magnetic fields, a兲 Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Also at Physique Statistique et des Plasmas, Université Libre de Bruxelles. Electronic mail: xalbets@ucy.ac.cy. 1070-6631/2011/23共4兲/047101/11/$30.00 certainly when the intensity of the Lorentz forces compared to viscous forces, as measured in terms of the Hartmann number Ha, is high 共see below for a precise definition of Ha兲. In that case, extremely thin boundary layers, called Hartmann layers, develop in the vicinity of walls perpendicular to the magnetic field and the flow exhibits sharp gradients in that region; in the rest of the pipe, the flow mostly adopts a uniform core in the direction of the magnetic field. At high values of Ha, the governing equations can however be simplified and approximate analytical solutions can be obtained through asymptotic methods that assume an inviscid and inertialess core surrounded by the thin exponential Hartmann layers. In the case of the homogeneous, laminar, MHD pipe flow, this framework was successfully applied in Refs. 7–9. Recently, this geometry has been reinvestigated using numerical simulations and the presence of overspeed regions in the side-layers 共region where the wall is parallel to the magnetic field兲 has been demonstrated for certain values of the wall conductivity.10 The study of the MHD pipe flow in a nonuniform magnetic field is noticeably more difficult. Here we focus our attention on the flow in a weakly conducting pipe that exists a region of space embedded in a strong magnetic field 共fringing magnetic field兲. This configuration has been analyzed analytically through an asymptotic calculation in Ref. 11 and the major characteristics of the flow could be described 共see also Ref. 12兲. In particular, the authors showed how the fully developed flow present in the upstream part of the pipe was redistributed in the fringing region to form two high speed jets in the side-layers and a low velocity core; this redistribution was also shown to induce a very important additional 23, 047101-1 © 2011 American Institute of Physics This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-2 Albets-Chico et al. pressure drop. This era also saw the birth of a powerful modeling technique of liquid-metal flows under the influence of strong magnetic fields.13,14 In this method, referred to as the core flow approximation, one assumes that within the core flow, inertia and viscous effects are negligible. This implies that momentum conservation reduces to a linear equation expressing the balance between the pressure gradient and the Lorentz force. Upon integration of the three-dimensional 共3D兲 problem along the magnetic field lines, the problem then reduces to a two-dimensional 共2D兲 system for three unknown functions, thereby greatly reducing the computational cost.15 In the case of the MHD pipe flow in a fringing magnetic field, the core flow approximation has been implemented in various numerical codes16–23 and compared to the asymptotic analysis of Ref. 11 or experimental studies of this flow configuration.16,24–26 Although the core flow approximation is a powerful tool for investigating numerically MHD flows at high Hartmann numbers in relatively complex geometries, it does not come without limitations. First, for flows in which inertia plays a significant role, it cannot provide an accurate description; second, a finite 共and strong兲 magnetic field must be applied everywhere in the computational domain to fulfill its assumptions. Regarding the role of inertia, its magnitude depends on the particular flow considered but in general it is more important for cases where the magnetic field is less intense and the wall conductivity of the duct assembly is low 共the braking effect of the Lorentz force is then globally small since the current loops close mostly within the fluid兲. Several authors have assessed this issue and compared the accuracy of the core flow approximation against more complete numerical solutions 共see for example Refs. 22, 27, and 28兲 but given the extremely high computational requirements, these studies have been limited to cases at moderate Hartmann numbers. As a consequence, the range of parameters for which the core flow approximation offers enough precision is still an open question. For instance, for the geometry and parameters we consider, the authors in Refs. 16 and 19 concluded that the agreement between the core flow approximation and experimental data was excellent. This conclusion was reached by examining data for the pressure over the whole pipe and the velocity profiles up to a short distance downstream of the magnetic field’s inflection point. For even lower values of the Hartmann number 共Ha⬇ 300兲 and for a similar test case, the authors of Ref. 29 also concluded that the core flow approximation and a full solution of the 3D MHD equations agree well in terms of core velocity. Based on these findings and order of magnitude estimates, the core flow approximation has been used in several engineering studies of the MHD pipe flow in a fringing magnetic field with values of the Hartmann number in the outlet region as low as 20 or 200 共see, e.g., Ref. 22兲. However, as we will show later in this article, this approach is not valid for subtle quantities like velocity profiles at specific downstream positions 共the later were not explored in previous studies兲. Finally, we recall that the second limitation of the core flow approximation implies that it cannot address the transition of flows from a high magnetic field region to another in which no magnetic field is present since it requires high Hartmann Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 numbers everywhere in the domain. In the case of fringing fields, it cannot predict velocity profiles as the flow moves away from the magnets and in particular it cannot capture the possible transition to turbulence occurring downstream. Following this discussion, one easily understands the practical difficulty in applying the core flow approximation in the case of fringing magnetic fields: to satisfy its assumptions, a sufficiently high outlet magnetic field has to be applied; however, the lowest possible value has to be chosen to obtain the correct physical behavior of the flow away from the magnets. As reckoned by several authors,19,28,29 high resolution numerical solution of the 3D MHD equations are then indispensable to fully validate the core flow approximation for a given geometry and flow parameters. The objective of this paper is to study the case of the MHD pipe flow with poorly conducting wall in the presence of a fringing magnetic field, by numerically computing full solutions of the quasistatic MHD equations. Given the progress in numerical algorithms and the access to higher computational resources, full solutions are now available for flow regimes at high Hartmann numbers that are relevant for fusion applications. Our test case is based on previously performed experiments16,30,31 and is a benchmark problem of the International Energy Agency 共IEA兲 Implementing Agreement on Nuclear Technology of Fusion Reactors 共Annex 01, Tritium Breeding Blanket, Radiation Shielding and Tritium Processing Systems of Fusion Reactors兲.32 This case was briefly considered in Refs. 33 and 34 to assess the performance of a novel discretization of the Lorentz force in the finite volume framework. Here, we extend the results in several ways. First we consider a much longer computational domain downstream of the fringing field region. This allows us to examine the evolution of the jets in the weak magnetic field region and demonstrate the transition to turbulence of the flow that was not documented in any previous studies. Also, we make a careful comparison of our results with the core flow approximation and explicitly evaluate both the roles of inertia and of the nonzero outlet magnetic field necessary for this approximation. Even though full solutions of the MHD equations at high Hartmann numbers become more easily obtainable, they still require very large resources for cases such as the one considered in this paper. For this reason, we limit our attention to the parameters of the benchmark case and we do not perform a systematic parametric study for the geometry considered. We also deliberately only describe qualitatively the transition to turbulence occurring at the outlet of the pipe since the simulations could not be run long enough to gather reliable statistics such as turbulence intensities etc. Indeed, the time step required by the intense magnetic field is two orders of magnitude smaller than the turbulent hydrodynamic one. The paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we define the test case considered and recall the governing equations, along with the proper boundary conditions. Sec. III is devoted to the numerical aspects; in particular, we describe the numerical algorithm 共based on a finite volume discretization兲 and the grid used. In Sec. IV, we present the computational results that include the pressure gradient, velocity profiles This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-3 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Direct numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow tw = 3.27 ⫻ 10−3 m, outlet y x z M d fiel etic n ag (x) = By where U is the average flow velocity, tw is the pipe’s wall thickness and w is the wall’s electrical conductivity. To obtain nondimensional equations, we rescale the variables as follows: u → Uu, B → B01y, ⵜ → R−1ⵜ, t → 共R / U兲t, j → UB0j, → RUB0, and p → U2 p. Here B0 is the intensity of the magnetic field at the inlet section of the pipe. The momentum balance and Ohm’s law then read, D=2R x=15 R inlet 30 R x=-15 R FIG. 1. Geometry of the duct and magnetic field. The dimensions are reported in multiples of the duct radius. and momentum budget. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Sec. V. II. PROBLEM DESCRIPTION 冉 A. Geometry and governing equations The geometry considered 共see Fig. 1兲 is based on experiments conducted at Argonne’s Liquid Metal Experiment 共ALEX兲 facility.16,30 It consists of a straight circular duct in which a liquid-metal flow exits from a region subject to an intense magnetic field 共the exact form of the magnetic field is given in Sec. II B兲. As stressed above, this type of flow is very important in the design of nuclear fusion blankets. The length unit is chosen as the pipe radius R and the whole computational domain spans 30R. The axis of coordinates are placed at the geometrical center of the pipe and the x direction is aligned with its axis. For most laboratory flows involving liquid metals, the so-called quasistatic approximation of the MHD equations35 holds. The momentum balance can then be written as: u + u · ⵜu = − ⵜ共p/兲 + ⵜ2u + 共1/兲j ⫻ B, t 共1兲 j = 共− ⵜ + u ⫻ B兲, 共2兲 ⵜ · u = 0, 共3兲 ⵜ · j = 0. 共4兲 In the above equations, u , B , j , p , , , , denote respectively the velocity field, the imposed magnetic field, the electric current, the pressure, the electric potential, the density of the fluid, its viscosity and its electric conductivity. The extra term appearing last in the RHS of Eq. 共1兲 is traditionally referred to as the Lorentz force. The electric potential can be obtained by solving the Poisson equation, ⵜ2 = ⵜ · 共u ⫻ B兲 resulting from Eqs. 共2兲 and 共4兲. The ALEX experimental flow conditions can be reproduced by adopting the parameters defined in the IEA liquid breeder blanket subtask benchmark problem definition referred to in the Introduction: = 2.80 ⫻ 106 S/m, U = 0.07 m/s, = 865 kg/m3, = 9.5 ⫻ 10−7 m2/s, 冊 1 2 u + u · ⵜu = − ⵜp + ⵜ u + Nj ⫻ 1y , Re t 共5兲 j = − ⵜ + u ⫻ 1 y . 共6兲 The two nondimensional numbers appearing in Eq. 共5兲 are the 共bulk兲 Reynolds number Re and the interaction parameter N, Re = R = 0.0541 m, w = 1.39 ⫻ 106 S/m. UR , N= B20R . U 共7兲 From Eq. 共5兲, we clearly see that inertia will be negligible compared to the Lorentz force when N is large and that viscous contributions will also be small for high values of the Hartmann number, Ha = 冑N Re = BR 冑 . 共8兲 In that case, the flow evolution is governed by the balance, ⵜp = Nj ⫻ 1y , 共9兲 which together with appropriate boundary conditions to take into account the Hartmann layers, constitutes the basis of the core flow approximation.15 In the case of a spatially varying magnetic field, N is a function of space, based on the local strength and direction of the magnetic field. Finally, we note that based on the benchmark parameters, the bulk velocity Reynolds number is, 共10兲 Re = 3986. B. Imposed magnetic field In the ALEX facility, the magnetic field is produced by an iron core electromagnet capable of generating a highly uniform 2.08 T field in a region that spans 0.76 m wide ⫻ 1.83 m long. At the outlet of the electromagnet, the magnetic field decays rapidly and its y-component can be approximated by the following fit function: Bexp y 共x兲 = Binlet 1 − tanh关␥共x/R + d兲兴 . 2 共11兲 We note that the above formula allows a nearly perfect fit of the available experimental data. Binlet is the intensity of the magnetic field inside the magnet 共where it is uniform兲, ␥ is a decreasing factor and d is a coordinate dependent translation parameter relative to the inflection point of the magnetic field. Formula 共11兲 has already been used in several other studies of liquid-metal flows exiting a region of intense magnetic field19,33,34 and is also part of the IEA liquid breeder This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-4 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Albets-Chico et al. blanket subtask benchmark problem definition. Unfortunately, since it is not available and to allow a fair comparison with the core flow approximation, Bx is set to zero so that the magnetic field has a nonzero curl. In order to match the experimental magnetic field we have, Binlet = 2.08 T, ␥ = 0.45, d = − 0.33. 共12兲 The above magnetic field allows a direct comparison with the experimental results.16 However, we are also interested in the comparison of the full solution data with results obtained through the core flow approximation. For that reason, we also consider a second magnetic field given by, Bcfa y 共x兲 = 再 Bexp y 共x兲 for x ⬍ 3.6, 0.05Binlet for x ⱖ 3.6. 冎 共13兲 冑 = 6569, N = Ha2/Re = 10824. n = ⵜ · 共cⵜ兲 共at the walls兲, 共14兲 共15兲 In the outlet region, we have Ha→ 0 or Ha= 330 respectively for the cases FSBexp or FSBcfa. C. Boundary conditions At the walls, the velocity satisfies the no-slip condition uwall = 0. At the entrance of the pipe 共inlet兲, the velocity field has to be specified. The profile is chosen as the solution of a laminar pipe flow subject to a homogeneous magnetic field and obtained through an independent numerical simulation 共see Ref. 10 for details兲. At the outlet of the pipe, the convective 共or nonreflective兲 boundary condition for the velocity is adopted: 共u / t兲 + Uconv共u / n兲 = 0. Uconv = 共1 / S兲兰outletu · ndS is the bulk velocity computed at the outlet cross section S and n is the outward normal unit vector. The boundary conditions for the Poisson equation determining the electric potential are more intricate. First, we assume that the walls are thin compared to the pipe’s radius. In that case, we can use the so-called thin wall approximation,36 共16兲 where ⵜ stands for the component of the ⵜ-operator tangential to the wall. c is the so-called wall-conductance ratio defined as c = 共wdw / R兲, w and dw being, respectively, the wall conductivity and thickness 共here c = 0.027兲. It is easily seen that in the limit of perfectly conducting 共insulating兲 walls, we recover the familiar Dirichlet 共Neumann兲 condition. At the inlet of the pipe, we impose that no electric currents are entering the domain. Combining Eq. 共2兲 and u 储 n at the inlet, we get: 共 / n兲兩inlet = 0. Indeed, one of the main assumptions of the core flow approximation is that the Hartmann number is very high and therefore the magnetic field’s intensity cannot decrease toward zero for large values of x. The core flow approximation results presented later in this paper 共L. Bühler, private communication兲, are obtained using the same outlet residual field 共0.05Binlet兲. We note however that for x ⬍ 3.6, they are not computed with the magnetic field based on the fitting function but from interpolated values of the experimental magnetic field 共this results in a difference of maximum 1%兲. In the far downstream region, the flow will essentially be a hydrodynamic flow when Bexp y is used while it will remain strongly influenced by the magnetic field when Bcfa y is used. Numerical results obtained with either fields are referred to in the sequel as cases FSBexp and FSBcfa. Based on bulk flow quantities and given the imposed magnetic field, we have the following values for the Hartmann number and interaction parameter in the inlet region: Ha = BR which assumes that currents discharge tangentially in the wall 共i.e., they have no normal component兲. This condition reads: 共17兲 At the outlet, we also impose that no electric current leaves the domain.37 The general boundary condition is thus, 共 / n兲 兩outlet = 共u ⫻ B兲 · n. However, for the cases we consider, this relation reduces again to, 共 / n兲兩outlet = 0. 共18兲 Indeed, as described above, we either consider that: Boutlet ⬇ 0 or that Boutlet is sufficiently large so that any turbulence produced in the fringing region is damped before reaching the outlet 共as a consequence, u 储 n in that region兲. III. NUMERICAL ASPECTS A. Numerical Algorithm Our computations are performed using the CDP code developed at the Center For Turbulence Research 共Stanford/ NASA Ames兲. The details of the code have been described extensively in Refs. 38–41 and benchmarked in a variety of hydrodynamic complex flows. For this study, we have complemented this code with a module to compute the Lorentz force and include it in the momentum balance. The implementation and integration of this module in CDP has been validated for several MHD flows and in various geometries including the MHD channel flow,42 the MHD duct flow 共Hunt’s case兲43 and the MHD pipe flow.10,44,45 Below, we provide an extra validation of the code in the present test case by comparing our results with those obtained by another independent finite volume solver.33,34 CDP uses a collocated finite volume discretization of the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations in a node-based formulation. A typical grid element is illustrated in Fig. 2. The label C corresponds to the location of the centroid of the element in the original volume-based grid. In the dual mesh, the node-based control volumes are centered around each of the vertices 共nodes兲 of this original mesh. In the figure, P represents such a node of the dual mesh. The variables 共ui , ji , p , 兲 are stored at these nodes and the 共independent兲 face normal velocity U f are stored at the centroid of the dual volume’s faces. The discrete equations of motion are solved using the following fractional step method: This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-5 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Direct numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow 5 n + 1 / 2, through the Poisson system defined by the incompressibility condition, 6 3 共1/⌬t兲 兺 u쐓i,f ni,f A f = 兺 共 j pn+1/2兲 f n j,f A f . 4 f C 1 P E (ui, ji , p, φ) In Eq. 共25兲, the face normal flux of the pressure gradient is computed through: 共 j pn+1/2兲 f n j,f = 2 f’ F Uf FIG. 2. 共Color online兲 Illustration of the collocated mesh. The shaded area represents a face belonging to the dual mesh. ûi,P − uni,P V P + 兺 Un+1/2 un+1/2 Af f i,f ⌬t f f 共19兲 共20兲 쐓 un+1 i,P − ui,P = − 共i p兲n+1/2 . P ⌬t 共21兲 In the above equations, V P is the volume of the control volume surrounding point P and the sums are extended to all faces f delimiting this control volume. The face areas are denoted A f and their unit normal vectors are written ni,f . Variables have the subscripts P or f depending on whether they are evaluated at the center of the control volume or the face. For any quantity , the interpolation from nodal to face values is done through the following expression: P + nbr , 2 共27兲 Un+1 = u쐓i,f ni,f − ⌬t共n p兲n+1/2 . f f 共28兲 In Eq. 共27兲, the node value of the pressure gradient is computed by making use of the discrete Gauss theorem which expresses the derivative of a quantity with a summationby-part 共SBP兲 operator,41 to provide corrections for skewed or stretched elements: f u쐓i,P − ûi,P = 共i p兲n−1/2 , P ⌬t 共兲 f = 共26兲 쐓 n+1/2 , un+1 i,P = ui,P − ⌬t共i p兲 P 共 i 兲 PV P = 兺 兺 = − 共i p兲n−1/2 V P + N关jnP ⫻ 1y兴i P 1 共 jun+1/2 兲 f n j,f A f i Re n+1/2 pnbr − pn+1/2 P , 储x j,nbr − x j,P储 where xi,P are the coordinates of P 共an identical expression is 兲 f n j,f in 共19兲 as a semi-implicit also used to evaluate 共 jun+1/2 i contribution兲. Once the pressure is known, the nodal and face normal velocities are updated using: nbr f +兺 共25兲 f 共22兲 where the subscript nbr denotes the node located on the other side of f, with respect to P. We further have, 3 1 = Unf − Un−1 , Un+1/2 f 2 2 f 共23兲 1 = 共ûi,f + uni,f 兲. un+1/2 i,f 2 共24兲 In other words, the face normal velocity is advanced in time using the Adams–Bashforth scheme, while the Crank– Nicholson advancement scheme is used for the nodal velocity. Equation 共21兲 is used to compute the pressure at step f⬘ E + F + C ni,f ⬘A f ⬘ . 3 共29兲 E, F, and C are respectively the center of the edge between P and nbr, the center of the considered control volume face and the center of the control volume. In this scheme, each face is thus decomposed into several subfaces f ⬘ and the subface value is obtained by averaging over its circumcenter values. For example, in the case of the cartesian dual-mesh cell illustrated in Fig. 4, E = 共 P + nbr兲 / 2, F = 共 P + nbr + 1 + 2兲 / 4, and C = 共 P + nbr + 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6兲 / 8. As seen in Eq. 共19兲, the MHD term 共Lorentz force兲 is treated explicitly as an additional force term. At high Hartmann numbers, this severely limits the time-step to ensure numerical stability. For example, at Ha= 7000, the time-step size is two orders of magnitude smaller than the one needed for the turbulent hydrodynamic flow at the same bulk Reynolds number. Also, from the spatial discretization point of vue, the accurate computation of the Lorentz force is the most challenging aspect in the full solution calculations of MHD flows at moderate and high Hartmann numbers. As seen from Ohm’s Law 关Eq. 共2兲兴, the current density depends on the difference between ⵜ and u ⫻ B. Any error in this difference is then multiplied by the interaction parameter 共when the equations are written in nondimensional form兲 for computing the Lorentz force 关see Eq. 共5兲兴. This may generate an error in the momentum balance that can in some cases be larger than the other terms present by several orders of magnitude 共depending on the Ha and the boundary conditions for the electric potential兲, resulting in heavily inaccurate predictions of the flow behavior. An extensive description of the different ways to discretize the Lorentz force is given in Ref. 34 共see also Ref. 46 for a recent new proposal兲. In particular, the authors of Ref. 34 advocate the use of a so-called “con- This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-6 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Albets-Chico et al. O(Ha−1 cos θ) Hartmann layers 1 θ θ n 0.5 O(Ha−1/3 ) u B O(Ha−2/3 ) y/R r 0 Core -0.5 y Roberts layers z -1 -1 x sistent and conservative” discretization that guarantees that no global spurious Lorentz force is added to the momentum balance because of interpolation errors. While this is an essential and desired feature when the solid walls are electrically insulating 共in that case all the currents loop in the fluid domain and the net induced Lorentz force vanishes兲, we have observed in our case that this discretization leads to a more unstable numerical solution. This was apparently not observed in the work of Ref. 34, but we note that their analysis was conducted on a cell-centered spatial grid while our code 共CDP兲 uses a node-based grid. For this reason, we have adopted a conventional discretization of ohm’s law that is adequate for electrically conducting walls when the flow phenomenology is dominated by the extremely large Lorentz force braking: 1 兺 兺 nf ⬘A f ⬘n f ⬘ + unP ⫻ 1y . V P faces f 0 0.5 1 z/R FIG. 3. Cross section of a circular duct and flow subregions at high Ha numbers. jnP = − -0.5 共30兲 ⬘ In Eq. 共30兲, f ⬘ is the electric potential value at the subface f ⬘ 共Fig. 2兲 and it is obtained by discretizing the Poisson equation ⵜ2 = ⵜ · 共u ⫻ 1y兲 in exactly the same way as the pressure Poisson problem. B. Numerical grid In MHD flows, the boundary layers may become extremely thin at moderate and high Ha numbers. For example, for an infinite circular duct 共see Fig. 3兲, the thickness of the Hartmann layer is inversely proportional to the Ha number, i.e., ␦Ha = O共Ha−1兲, and the dimensions of the Roberts 共side兲 layers47 scale as ␦y ⫻ ␦z = O共Ha−1/3兲 ⫻ O共Ha−2/3兲. At high Hartmann numbers, these layers might be significantly thinner than traditional hydrodynamic viscous layers. Here we use a mesh of the type represented in Fig. 4. It is structured and made of quadrilateral elements in the boun- FIG. 4. Cross-section of the mesh used. drary layer, while in the core it is unstructured and made of triangular elements. The streamwise direction 共x兲 grid is structured, with 750 elements. The circumference 共 兲 has been meshed with 156 elements at the pipe’s wall, i.e., at r = R. The boundary layer region is meshed with 19 points in the radial direction. The first point is located at a distance 5 ⫻ 10−5R from the wall. The grid spacing is then progressively increased by a stretching factor of 1.424 between two consecutive points until the core part of the grid is reached. A posteriori, we determined to have a minimum of 7 points in the radial direction to capture the Hartmann layer, even at the inlet of pipe where Ha is the largest. In the core, the grid along the radius 共r兲 is unstructured and approximately composed of 50 elements. Overall, the mesh sizes are also fine enough to simulate a turbulent hydrodynamic pipe flow at Reynolds number Re ⬇ 4000 or Re ⬇ 500. Indeed, in terms of wall units, we have + + + = 10.4, ⌬rmax ⬃ 10.2, and ⌬rmin = 0.013, ⌬x+ = 10.4, ⌬max which are similar to the values used in Refs. 48–50 共except + which has to be significantly lower here of course for ⌬rmin to accommodate for Hartmann layers兲. As an initial test of the numerical algorithm and the mesh quality, we have compared the prediction of the code and those of the core flow approximation for a straight pipe subjected to a homogeneous magnetic field with Re= 3986, Ha= 6569, and c = 0.027 共the core flow approximation is very accurate for this fully developed flow兲. For these parameters, the bulk velocity and the centerline velocity agree within 0.3% and 0.02%, respectively. In the next section, our computations are benchmarked against experimental results, the core flow approximation and earlier computations by Refs. 33 for the flow described in Sec. II A. IV. RESULTS A. Pressure gradients The first diagnostics we consider 共Figs. 5 and 6兲 are the pressure gradients, measured along the pipe’s wall at, y = 0 , z = R and y = R , z = 0. Overall, the agreement between This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-7 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Direct numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow 0.05 0.02 P (x0R)−P (xR0) Rσ U b B 2 ∂p/∂x(x,0,R) σUb B 2 0.025 0.015 FSBcfa 0.01 FSBcfa 0.005 Exp. [16] Core flow approx. 0 Ni et al. [32] −0.005 −15 −10 −5 FSBexp FSBcfa 0.04 Exp. [16] 0.03 Core flow approx. Ni et al. [32] 0.02 0.01 0 0 X/R 5 10 15 FIG. 5. Streamwise pressure gradient along the axis y = 0 , z = R 共the cases DNSBexp and DNSBcfa cannot be distinguished兲. our full solution and the one obtained in Ref. 33, the core flow approximation and experimental results is excellent 共unfortunately, experimental results are not available along the axis y = R , z = 0兲. We only note a slight difference between our full solution and the one obtained in Ref. 33 for the inlet of the pipe. We could not explain this difference but observe that our results are in complete agreement with the core flow approximation. Comparing the cases FSBexp and FSBcfa we conclude that the nonzero Boutlet used here has no influence on the pressure drop 共the curves cannot be distinguished兲. The reason is of course that the upstream pressure drop is two orders of magnitude larger than the downstream pressure drop. From the comparison of case FSBcfa and core flow approximation results, we also note that inertial effects are negligible as far as the pressure drop is concerned. Exactly the same conclusions can be drawn from Fig. 7 where the transverse pressure difference is plotted. However, we note a mismatch of about 15% of the maximum transverse pressure difference between the full solutions and the 0.04 −0.01 −15 −10 −5 0 X/R 5 10 15 20 FIG. 7. Transverse pressure difference along the pipe 共the cases DNSBexp and DNSBcfa cannot be distinguished兲. core flow approximation when compared to the experiments. A similar difference was reported in Ref. 51 where the authors show that by using a 3D analytical model of the experimental magnetic field for the simulations, a better agreement is obtained. B. Velocity profiles and momentum budget In Fig. 8 we plot the streamwise velocity profile along the z-axis at x / R ⬇ 0 共i.e., at the inflexion point of the magnetic field’s profile兲. Overall, the agreement between our full solutions, the core flow approximation and experimental results is very good with slight deviations in the near wall region 共this diagnostic is not reported in Ref. 33兲. We note a slight change in the derivative of the full solution profile around z / R = ⫾ 0.9. As the flow is perfectly laminar until much further downstream in all cases, this observation cannot be related to an instability occurring in the boundary FSBexp FSBcfa FSBexp 0.03 Exp. [16] FSBcfa Core flow approx. 0.02 Core flow approx. Ni et al. [32] 0.01 0 −0.01 −15 −10 −5 0 X/R 5 10 15 FIG. 6. Streamwise pressure gradient along the axis y = R , z = 0 共the cases DNSBexp and DNSBcfa cannot be distinguished兲. FIG. 8. Normalized mean streamwise velocity as a function of z in the mid plane 共y = 0兲 at downstream position x / R ⬇ 0 共the cases DNSBexp and DNSBcfa cannot be distinguished兲. This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-8 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Albets-Chico et al. 1.2 30 1 Momentum budget U(x,0,0) Ub 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 FSBexp FSBcfa Exp. [16] −0.2 Core flow approx. −0.4 Ni et al. [32] −0.6 −20 Centerline (y=0,z=0) 20 0.8 10 0 -10 −ux ∂x ux −uz ∂z ux -20 −10 0 X/R 10 −∂x p 20 Njz By -30 FIG. 9. Normalized streamwise velocity as a function of x along the centerline 共y = 0 , z = 0兲. 4 6 8 x/R 10 12 14 FIG. 11. Streamwise momentum budget along the centerline 共y = 0 , z = 0兲. layer. Moreover, since the grid used changes from unstructured to structured elements in that region, this slight change in the derivative could have a local numerical origin. Finally, we also observe that at this streamwise location, the effect of the downstream magnetic field on this profile is negligible since the results for the cases FSBexp and FSBcfa cannot be distinguished. A better insight into the roles of inertia and the presence of a downstream magnetic field is obtained by considering streamwise velocity profiles along the direction of the pipe. Two such profiles are presented in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively, for the centerline 共y = 0 , z = 0兲 and the line 共y = 0 , z = 0.9R兲. Unfortunately, the full solution of Ref. 33 and the experimental data are only available up to x / R ⬇ 2. Up to this streamwise location, all full solutions, the core flow approximation and the experimental results are in excellent agreement. Further downstream, a significant difference between the profiles of our full solution 共case FSBcfa兲 and the core flow approximation is observed in both figures as the recovery to the fully developed MHD flow corresponding to the nonzero outlet field occurs faster in the framework of the core flow approximation. Indeed, for the centerline profile, both computational methods start to diverge around x / R ⬇ 3 while this occurs around x / R ⬇ 0 for the wall profile 共y = 0 , z = 0.9R兲. In order to trace the origin of these discrepancies, we plot in Figs. 11 and 12 for case FSBcfa, the contributions of the pressure gradient, the Lorentz force and inertia to the streamwise momentum budget. As recalled in the introduction, the core flow approximation assumes that the pressure gradient and the Lorentz force balance each other perfectly. For the centerline of the pipe, we observe in the simulations that this holds very accurately up to x / R ⬇ 4. However, Fig. 11 shows that for 4 ⱗ x / R ⱗ 11, the inertial contribution −uxxux is certainly nonnegligible when compared to the pressure gradient and the Lorentz force. On the line 共y = 0 , z = 0.9R兲, we also observe a very significant contribution of inertia for −2 ⱗ x / R ⱗ 10 共Fig. 12兲 共at x / R ⬇ 3.5, the flow undergoes a very sharp variation in space related to the discontinuity in the derivative of the magnetic field Bcfa y 兲. 300 7 FSBexp U(x,0,0.9R) Ub 5 200 FSBcfa Core flow approx. 4 Ni et al. [32] 3 2 1 0 −20 Line (y=0, z=0.9R) Exp. [16] Momentum budget 6 100 0 -100 −ux ∂x ux −uz ∂z ux −∂x p Njz By -200 −10 0 X/R 10 20 FIG. 10. Normalized streamwise velocity as a function of x along the line 共y = 0 , z = 0.9R兲. -300 -2 0 2 4 6 x/R 8 10 12 14 FIG. 12. Streamwise momentum budget along the line 共y = 0 , z = 0.9R兲. This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 1 1 1 1 1 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0 z/R 0 z/R 0 z/R 0 z/R Direct numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow z/R 047101-9 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -1 0 2 4 6 -1 0 4 6 -1 0 2 4 6 -1 0 4 6 -1 0 1 1 1 1 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0 0 z/R 0 z/R 0 z/R u/U b x/R=5 1 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -0.5 -1 0 2 4 6 -1 0 2 4 6 -1 0 2 4 6 -1 2 4 6 u/U b x/R=10 z/R u/U b x/R=0 2 z/R u/U b x/R=-10 2 u/U b x/R=-5 u/U b x/R=-5 0 0 0 2 4 6 -1 0 2 4 6 FIG. 13. Normalized mean streamwise velocity as a function of z in the midplane 共y = 0兲 at several downstream positions for the cases DNSBcfa 共top兲 and DNSBexp 共bottom兲. Interestingly, for 4 ⱗ x / R ⱗ 8, the Lorentz force is mostly compensated by the inertial term −uxxux. The fact that the pressure gradient is not exactly balanced by the Lorentz force, even for an outlet field corresponding to Ha= 330 共case FSBcfa兲, is certainly an important element giving rise to the differences in velocity profiles 共although other factors like the other simplifications of the core flow approximation or the slight difference in magnetic fields used 共see Sec. II B兲 could also play a role兲. Returning to Figs. 9 and 10, we also observe the impact of the nonzero cut-off magnetic field Boutlet downstream of x / R ⬇ 3.5 as the curves corresponding to FSBexp and FSBcfa start to diverge. As expected, the velocity profiles recover their inlet value when Boutlet ⫽ 0 共at high Hartmann numbers the fully developed MHD flow has a flat core and we must conserve inlet massflow兲, while this is not observed when Boutlet = 0 共see below兲. We also conclude that the influence of the nonzero outlet field does not propagate significantly upstream of the point from which it is applied. This drastic difference in velocity profiles is further illustrated in Fig. 13 where the streamwise velocity along the z-axis is plotted at several downstream locations. Up to x / R ⬇ 0 the cases FSBexp and FSBcfa provide nearly identical velocity profiles. Further downstream, the flow recovers the fully developed MHD profile as the side-wall jets are rapidly damped by the outlet magnetic field in the FSBcfa case. In the FSBexp case, the flow is governed by plain hydrodynamics after the exit of the magnet. We observe that the jets are significantly stronger than in the FSBcfa case and also that they persist much further downstream. In Fig. 14 two contour plots of the streamwise velocity profile are shown to highlight the different behaviors at the outlet of the magnetic field. In the FSBexp the jets become unstable and turbulence develops. At very far downstream positions 共not computed here兲, the flow ultimately would adopt the turbulent pipe flow profile since the Reynolds number is quite large 共Re= 3986兲. Of course, the core flow approximation cannot capture the transition to turbulence since its domain of validity does not extend outside the strong magnetic field region. V. CONCLUDING REMARKS In this paper we have described some numerical simulations of a liquid-metal flow that exits a region where an intense magnetic field is present 共flow in a fringing magnetic field兲. The chosen parameters are based on the IEA liquid breeder blanket subtask benchmark problem definition that correspond to experiments conducted at Argonne’s Liquid Metal Experiment facility. From the numerical point of view, the excellent agreement with experimental results demonstrate that full solutions on moderately sized clusters are now obtainable for this complex problem, even for parameters relevant to fusion blankets. For future comparison, we have provided complete descriptions of the numerical algorithm and mesh used. Our analysis also focuses on the comparison between full solution data and the core flow approximation. As far as the pressure drop is concerned, the results confirm that the core flow approximation constitutes a very valuable engineering tool for the configuration studied since this design parameter can be accurately predicted at a reduced computational cost. In a configuration with electrically insulating This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-10 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Albets-Chico et al. FIG. 14. 共Color online兲 Coutour plots of the dimensionless streamwise velocity 共ux / Ub兲 in the 共y = 0兲 plane for the cases DNSBcfa 共top兲 and DNSBexp 共bottom兲. boundaries, the situation could be different since the net braking Lorentz force is much smaller and inertia is expected to play a more significant role. As far as the velocity profiles are concerned, full solution computations and the core flow approximation are in excellent agreement up to approximately the streamwise location of the magnetic field’s inflection point. Beyond that point, two different flow behaviors are observed depending on the outlet magnetic field. If, as required by the core flow approximation, a nonzero outlet field is imposed, the velocity profiles computed through this method converge to the fully developed MHD profiles faster than observed with a full solution computation. By examining the momentum budget, we have provided evidence that this discrepancy is at least in part due to inertia, even though the Hartmann number and interaction parameters corresponding to the nonzero outlet field used here are still quite large 共Ha= 330 and N = 27, respectively兲. As expected, when the outlet magnetic field is set to zero, the velocity profiles are completely different. The side layer jets produced in the fringing magnetic field are not destroyed and persist throughout the rest of the computational domain. Beyond x / R ⬇ 10 and for the flow parameters chosen, a transition to turbulence is observed resulting from the high shear present at the sides of the jets. In order to better study this transition, a much longer computational domain and time evolution are required, both being beyond the scope of this work. In this regard, the fact that full solution computation allows a zero outlet magnetic field provides a significant advantage over the core flow approximation. Indeed, to properly predict local phenomena such as heat transfer and corrosion effects, a precise knowledge of velocity profiles and turbulence intensities is required. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are particularly grateful to Leo Bühler for providing the core flow approximation computational results used in this work. We also acknowledge fruitful discussion with Sergei Molokov, Stijn Vantieghem, Axelle Viré and Evgeny Votyakov. This work has been performed under the UCYCompSci project, the EURYI 共European Young Investigator兲 scheme and with financial support from a Marie Curie Transfer of Knowledge 共TOK-DEV兲 grant 共Contract No. MTKDCT-2004-014199兲 and a Center of Excellence grant from the Norwegian Research Council to the Center of Biomedical Computing. 1 L. Bühler, in Magnetohydrodynamics—Historical Evolution and Trends, edited by S. Molokov, R. Moreau, and H. K. Moffatt 共Springer, Dordrecht, 2007兲, pp. 171–194. 2 J. Hartmann, “Hg-dynamics I. Theory of the laminar flow of an electrically conductive liquid in a homogeneous magnetic field,” Det Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Mathematisk-fysiske Meddedelser XV共6兲, 1 共1937兲. 3 J. Hartmann and F. Lazarus, “Hg-dynamics II. Experimental investigations on the flow of mercury in a homogeneous magnetic field,” Det Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Mathematisk-fysiske Meddedelser XV共7兲, 1 共1937兲. 4 R. Gold, “Magnetohydrodynamic pipe flow. Part 1,” J. Fluid Mech. 13, 505 共1962兲. 5 S. Ihara, T. Kiyohiro, and A. Matsushima, “The flow of conducting fluids in circular pipes with finite conductivity under uniform transverse magnetic fields,” ASME J. Appl. Mech. 34, 29 共1967兲. 6 S. K. Samad, “The flow of conducting fluids through circular pipes having finite conductivity and finite thickness under uniform transverse magnetic fields,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 19, 1221 共1981兲. 7 A. Shercliff, “The flow of conducting fluids in circular pipes under transverse magnetic fields,” J. Fluid Mech. 1, 644 共1956兲. 8 A. Shercliff, “Magnetohydrodynamic pipe flow. Part 2,” J. Fluid Mech. 13, 513 共1962兲. This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22 047101-11 9 Phys. Fluids 23, 047101 共2011兲 Direct numerical simulation of a liquid-metal flow C. Chang and S. Lundgren, “Duct flow in magnetohydrodynamics,” Z. Angew. Math. Phys. XII, 100 共1961兲. 10 S. Vantieghem, X. Albets-Chico, and B. Knaepen, “The velocity profile of laminar MHD flows in circular conducting pipes,” Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 23, 525 共2009兲. 11 R. J. Holroyd and J. S. Walker, “A theoretical study of the effects of wall conductivity, non-uniform magnetic fields and variable-area ducts on liquid-metal flows at high hartmann number,” J. Fluid Mech. 84, 471 共1978兲. 12 J. S. Walker, “Liquid- metal flow in a thin conducting pipe near the end of a region of uniform magnetic field,” J. Fluid Mech. 167, 199 共1986兲. 13 A. G. Kulikovskii, “Slow steady flows of a conducting fluid at large hartmann numbers,” Fluid Dyn. 3, 1 共1968兲. 14 A. G. Kulikovskii, “Flows of a conducting incompressible liquid in an arbitrary region with a strong magnetic field,” Fluid Dyn. 8, 462 共1973兲. 15 U. Müller and L. Bühler, Magnetofluiddynamics in Channels and Containers 共Springer, Dordrecht, 2001兲. 16 C. B. Reed, B. F. Picologlou, T. Q. Hua, and J. S. Walker, “Alex results—a comparison of measurements from round and a rectangular duct with 3-D code predictions,” Proceedings of the IEEE 12th Symposium on Fusion Engineering 共IEEE, New York, 1987兲, Vol. 87, pp. 1267–1270. 17 H. Madarame and H. Tokoh, “Development of computer code for analyzing liquid metal MHD flow in fusion reactor blankets, 共i兲 flow in circular pipe under uniform transverse field,” J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 25, 233 共1988兲. 18 H. Madarame and H. Tokoh, “Development of computer code for analyzing liquid metal MHD flow in fusion reactor blankets, 共ii兲 flow in circular pipe under non-uniform transverse field,” J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 25, 323 共1988兲. 19 K. A. McCarthy, M. S. Tillack, and M. A. Abdou, “Analysis of liquidmetal MHD flow using an iterative method to solve the core flow equations,” Fusion Eng. Des. 8, 257 共1989兲. 20 T. Q. Hua and J. S. Walker, “Three-dimensional MHD flow in insulating circular ducts in non-uniform transverse magnetic fields,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 27, 1079 共1989兲. 21 L. Bühler, “Magnetohydrodynamic flows in arbitrary geometries in strong, nonuniform magnetic fields,” Fusion Technol. 27, 3 共1994兲. 22 S. Molokov and C. B. Reed, “Liquid metal magnetohydrodynamic flows in circular ducts at intermediate Hartmann numbers and interaction parameters,” Magnetohydrodynamics 39, 539 共2003兲. 23 S. Molokov and C. B. Reed, “Parametric study of the liquid metal flow in a straight insulated circular duct in a strong nonuniform magnetic field,” Fusion Sci. Technol. 43, 200 共2003兲. 24 R. J. Holroyd, “An experimental study of the effects of wall conductivity, non-uniform magnetic fields and variable-area ducts on liquid metal flows at high hartmann number. Part 1. Ducts with non-conducting walls,” J. Fluid Mech. 93, 609 共1979兲. 25 R. J. Holroyd, “An experimental study of the effects of wall conductivity, non-uniform magnetic fields and variable-area ducts on liquid metal flows at high hartmann number. Part 2. Ducts with conducting walls,” J. Fluid Mech. 96, 355 共1980兲. 26 K. Miyazaki, K. Konishi, and S. Inoue, “MHD pressure drop of liquid metal flow in circular duct under variable transverse magnetic field,” J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 28, 159 共1991兲. 27 G. Talmage, S. H. Shyu, M. J. Moeny, S. Tavener, and K. A. Cliffe, “Inertial effects on electrically conducting fluids in the presence of transverse magnetic fields: An example problem,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 36, 1 共1998兲. 28 K. A. McCarthy, A. Y. Ying, N. B. Morley, and M. A. Abdou, “Comparison of the core flow approximation and full solution approach for MHD flow in nonsymmetrical and multiple adjacent ducts,” Fusion Eng. Des. 17, 209 共1991兲. 29 L. Lenhart and K. McCarthy, “Comparison of the core flow solution and the full solution for MHD flow,” Tech. Rep. KfK 4681, Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe, 1990. 30 C. B. Reed, B. F. Picologlou, and P. V. Dauzvardis, “Experimental facility for studying MHD effects in liquid metal cooled blankets,” Fusion Technol. 8, 257 共1985兲. 31 B. F. Picologlou, C. B. Reed, and P. V. Dauzvardis, “Experimental and analytical investigations of magnetohydrodynamic flows near the entrance to a strong magnetic field,” Fusion Technol. 10, 860 共1986兲. 32 B. Neil, Morley, private communication. 33 M.-J. Ni, R. Munipalli, N. B. Morley, P. Huang, and M. A. Abdou, “Validation case results for 2D and 3D MHD simulations,” Fusion Sci. Technol. 52, 587 共2007兲. 34 M.-J. Ni, R. Munipalli, N. B. Morley, P. Huang, and M. A. Abdou, “A current density conservative scheme for incompressible MHD flows at a low magnetic Reynolds number. Part II: On an arbitrary collocated mesh,” J. Comput. Phys. 227, 205 共2007兲. 35 P. H. Roberts, An Introduction to Magnetohydrodynamics 共Elsevier, New York, 1967兲. 36 J. S. Walker, “Magnetohydrodynamic flows in rectangular ducts with thin conducting walls,” Journal de Mécanique 20共1兲, 79 共1981兲. 37 B. Mück, C. Günther, U. Müller, and L. Bühler, “Three-dimensional MHD flows in rectangular ducts with internal obstacles,” J. Fluid Mech. 418, 265 共2000兲. 38 K. Mahesh, G. Constantinescu, and P. Moin, “A numerical method for large-eddy simulation in complex geometries,” J. Comput. Phys. 197, 215 共2004兲. 39 K. Mahesh, G. Constantinescu, S. Apte, G. Iaccarino, F. Ham, and P. Moin, “Progress toward large-eddy simulation of turbulent reacting and non-reacting flows in complex geometries,” Annual Research Briefs 共Center for Turbulence Research, NASA Ames/Stanford University, Stanford, 2002兲 pp. 115–142. 40 F. Ham and G. Iaccarino, “Energy conservation in collocated discretization schemes on unstructured meshes,” Annual Research Briefs 共Center for Turbulence Research, NASA Ames/Stanford University, Stanford, 2004兲 pp. 3–14. 41 F. Ham, K. Mattsson, and G. Iaccarino, “Accurate and stable finite volume operators for unstructured flow solvers,” Annual Research Briefs 共Center for Turbulence Research, NASA Ames/Stanford University, Stanford, 2006兲 pp. 243–261. 42 A. Viré, D. Krasnov, T. Boeck, and B. Knaepen, “Modeling and discretization errors in large eddy simulations of hydrodynamic and magnetohydrodynamic channel flows,” J. Comput. Phys. 230, 1903 共2011兲. 43 M. Kinet, S. Molokov, and B. Knaepen, “Instabilities and transition in magnetohydrodynamic flows in ducts with electrically conducting walls,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 154501 共2009兲. 44 A. Thess, E. Votyakov, B. Knaepen, and O. Zikanov, “Theory of the Lorentz force flowmeter,” New J. Phys. 9, 299 共2007兲. 45 A. Viré, B. Knaepen, and A. Thess, “Lorentz force velocimetry based on time-of-flight measurements,” Phys. Fluids 22, 125101 共2010兲. 46 S. Smolentsev, S. Cuevas, and A. Beltrán, “Induced electric current-based formulation in computations of low magnetic Reynolds number magnetohydrodynamic flows,” J. Comput. Phys. 229, 1558 共2010兲. 47 P. H. Roberts, “Singularities of Hartmann layers,” Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 300, 94 共1967兲. 48 J. G. M. Eggels, F. Unger, M. H. Weiss, J. Westerweel, R. J. Adrian, R. Friedrich, and F. T. M. Nieuwstadt, “Fully developed turbulent pipe flow: A comparison between numerical simulation and experiment,” J. Fluid Mech. 268, 175 共1994兲. 49 R. Friedrich, T. J. Hüttl, M. Manhart, and C. Wagner, “Direct numerical simulation of incompressible turbulent flows,” Comput. Fluids 30, 555 共2001兲. 50 C. Wagner, T. J. Hüttl, and R. Friedrich, “Low-Reynolds-number effects derived from direct numerical simulations of turbulent pipe flow,” Comput. Fluids 30, 581 共2001兲. 51 E. V. Votyakov, S. C. Kassinos, and X. Albets-Chico, “Analytic models of heterogenous magnetic fields for liquid metal flow simulations,” Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 23, 571 共2009兲. This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 121.195.186.20 On: Mon, 24 Aug 2015 07:37:22