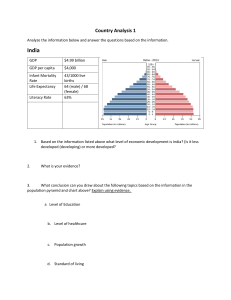

GDP and Unemployment: Measuring Economic Activity

advertisement