Statutory Construction: Definition, Characteristics, Purpose

advertisement

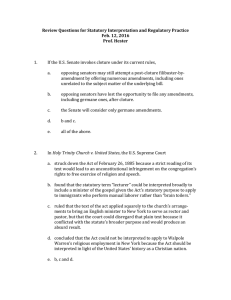

STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION From the book STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION: Concepts and Cases by Ricardo M. Pilares III *** CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. BACKGROUND 1. DEFINITION ARTICLE VIII, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution vests judicial power in the Supreme Court and such other courts established by law. Judicial Power includes “the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on any part of any branch or instrumentality of the government” “the right to determine actual controversies arising between adverse litigants, duly instituted in courts of proper jurisdiction” Often times requires the construction of statutes as applied in the case before them. Caltex (Philippines), Inc. v. Palomar defined construction as “the art or process of discovering or expounding the meaning and intention of the authors of the law with respect to the application to a given case, where that intention is rendered doubtful, amongst others, by reason of the fact that the given case is not explicitly provided for in the law” Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Law defines construction as “the act or result of construing, interpreting or explaining [the] meaning or effect [of a statute or contract] This subject is also called LEGAL HERMENEUTICS, which is defined as “the systematic body of rules which are recognized as applicable to the construction and interpretation of legal writings” 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF CONSTRUCTION Based on the definition provided in Caltex (Philippines), Inc. v. Palomar, statutory construction may be broken down into the following characteristics: a. It Is An Art Or Process Construction is not an exact science. It does not depend on a set of formulas that can be readily applied in every case. In fact, a statute may be interpreted differently if different maxims of construction are applied. The different principles of statutory construction should not be used if its application will run counter to the clear legislative intent which can be determined from the other parts of the law. NATURE OF CONTRUCTION In Cagayan Valley Enterprises, Inc. v. Court of Appeals the Supreme Court discussed that the very nature of construction is to determine the intention of the legislature, lends itself to subjectivity and uncertainty. EXAMPLES: The doctrine of last antecedent which is defined as “qualifying words and phrases normally refer to the last antecedent word or phrase, unless the context otherwise provides” was not adopted in the case of Tañada v. Tuvera which involves the interpretation of Article 2 of the Civil Code, where the Court held that the phrase “unless otherwise provided” does not qualify its immediate antecedent, which is the requirement of publication, but rather the period of publication which is stated at the beginning of the provision. In the case of Philippine American Drug, Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue held that the doctrine of ejusdem generis is but a rule of construction adopted as an aid to ascertain and give effect to legislative intent but that the same “should not be given such wide application that would operate to defeat the purpose of the law.” These cases show that the mere fact that the words of the statute are organized in a manner contemplated by a rule of construction does not automatically mean that such rule should be applied. The canons of construction should be considered as auxiliary rules of construction which are neither universal nor conclusive in application. Thus, as held in Primero v. Court of Appeals, “it should be applied only as means of discovering legislative intent which is not otherwise manifest and should not be permitted to defeat the plainly indicated purpose of the legislature.” In Philippine American Drug Co. decision, a canon of construction is not conclusive simply because the words used in the statute, or the syntax of the provision calls for the application of the same. Using different canons of construction can result in different interpretations. b. It Involves The Determination Of Legislative Intent In Senarillos v. Hermosisima, the Court held that the judicial interpretation of statutes constitutes part of the law as of the date the law was passed, since said construction merely establishes the legislative intent that the interpreted law carried into effect. Thus, when the courts construe a law, they are merely affirming what was originally intended by the legislature in enacting the same. In Torres v. Limjap, it held that the intent of the law-maker should always be ascertained and given effect, and courts will not follow the letter of a statute when it leads away from the true intent and purpose of the Legislature and to conclusions inconsistent with the spirit of the act. It further held that the intent is the vital part, the essence of the law, and the primary rule of construction is to ascertain and give effect to that intent. Intent is the spirit which gives life to a legislative enactment. In Araeta v. Dinglasan, the Court held that a rule must be tested according to its results, that is, the intention of the law in question must be sought for in its nature, the object to be accomplished, the purpose to be subserved and its relation to the Constitution. c. It Is Necessary When The Legislative Intent Cannot Be Readily Ascertained From The Words Used In The Law As Applied Under A Set Of Facts In Bolos v. Bolos, the Court explained that the cardinal rule in statutory construction is that when the law is clean and free from any doubt or ambiguity, there is no room for application. As the stature is clear, plain and free from ambiguity, it must be given its literal meaning and applied without attempted interpretation. This is what is known as the plain-meaning rule or verba legis. It is expressed in the maxim, index animi sermo, or ‘speech is the index of intention’. Furthermore, there is the maxim verbal egis non est recedendum, or ‘from the words of a statute there should be no departure. In People v. Mapa, the Supreme Court held that its first and fundamental duty is to apply the law. The court further held that “construction and interpretation come only after it has been demonstrated that application is impossible or inadequate without them. In Daoang v. Municipal Judge of San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte the court held that construction is only necessary only if the law is ambiguous. Thus “the rule is that only statutes with an ambiguous or doubtful meaning may be subject of statutory construction.” In Del Mar v. PAGCOR, the Supreme Court defined a statute to be ambiguous when “it is capable of being understood by reasonably well-informed persons in wither two or more senses.” In People v. Nazario, the Court held that the test to determine whether a statute is vague is when it lacks comprehensible standards that “men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application.” It cannot be presumed that laws intend an absurdity, and the courts should construe laws as to avoid it. Complied by: Dania S. Alcoran Page 1 of 4 STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION From the book STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION: Concepts and Cases by Ricardo M. Pilares III TESTS TO DETERMINE AMBIGUOUS: 1. WHETHER A STATUTE interpreting statutes do not enjoy the same level of recognition as decisions of the Supreme Court, which form part of the legal system under Article 8 of the Civil Code. A wrong construction of the law by an administrative agency does not create vested rights and such wrong interpretation cannot place the government in estoppel to correct or overrule the same. IS TEST OF MULTIPLE INTERPRETATIONS – when the statute is capable of two or more reasonable interpretations, such that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application. 2. TEST OF IMPOSSIBILITY – when literal application is impossible or inadequate. 3. TEST OF ABSURDITY OR UNREASONABLENESS – when a literal interpretation of the statute leads to an unjust, absurd, unreasonable or mischievous result, or one at variance with the policy of the legislation as a whole. 3. PURPOSE The purpose of statutory construction is to determine legislative intent when the same cannot be readily ascertained from the plain language of the law. Its primary consideration is the determination of legislative intent. – Tañ ada v. Yulo “The purpose of all ruled or maxims as to the construction or interpretations of statutes is to discover the true intention of the law.” – Tañ ada v. Cuenco, et al. d. It Is A Judicial Function In In re: R. McCulloch Dick, the court held that under the Philippine system of government, the duty and ultimate power to construe the laws is vested in the judicial department. In Endencia v. David, the court explained that the interpretation and application of said laws belong exclusively to the Judicial department. Defining and interpreting the law is a judicial function and the legislative may not limit or restrict the power granted to the courts by the Constitution. Whenever a statute is in violation of the fundamental law, the courts must so adjudge and thereby give effect to the Constitution. Any other course would lead to the destruction of the Constitution. Under the American system of constitutional government, among the most important functions intrusted to the judiciary are the interpreting of Constitutions and, as a loosely connected power, the determination of whether laws and acts of the legislature are or are not contrary to the provisions of the Federal and State Constitutions. The rule is recognized elsewhere that the legislature cannot pass any declaratory act, or act declaratory of what the law was before its passage, so as to give it any binding weight with the courts. A legislative definition of a word used in a s statute is not conclusive of its meaning as used elsewhere; otherwise, the legislature would be usurping a judicial function un defining a term. Under the principle of effectiveness, a statute must be read un such a way as to give effect to the purpose projected in the statute. The purpose of construction is to discover the intention of the law, and not to create doubt. In City of Baguio v. Naga, the Court held that the true object of all interpretation is to ascertain the meaning and will of the law-making body, to the end that it may be enforced. In varying language, the purpose of all rules or maxims in interpretation is to discover the true intention of the law. The spirit or intention of a statute prevails over the letter thereof. A statute should be construed according to its spirit and reason, disregarding as far as necessary, the letter of the law. By this, we do not correct the act of the Legislature, but rather … carry ut and give due course to its true intent. 4. THEORIES OF INTERPRETATION There are varying theories in statutory interpretation: 1. Textualist theory or originalism The legislature cannot, upon passing a law which violates a constitutional provision, validate it so as to prevent an attack thereon in the courts, by a declaration that it shall be so construed as not to violate the constitutional inhibition. Note that the principle that statutory construction is inherently a judicial function does not preclude Congress from enacting curative legislations. Furthermore, in Philippine Duplicators, Inc. v. NLRC, et al held that the contemporaneous construction of laws by agencies tasked with the implementation of the same is highly persuasive. It held that “the principle that contemporaneous construction of a statute by the executive officers of the government whose duty it is to execute it, is entitled to great respect, and should ordinarily control and construction of states by the courts, is so firmly embedded in our jurisprudence that n authorities need be cited to support it. In Laxamana v. Baltazar, the Court further added that “where a statute has received a contemporaneous and practical interpretation and the statute as interpreted is re-enacted, the practical interpretation is accorded greater weight than it ordinarily receives, and is regarded as presumptively the correct interpretation of the law. Furthermore, “the rule x x x is based upon the theory that the legislature is acquainted with the contemporaneous construction of a statute, especially when made by an administrative body or executive officers charged with the duty of administering or enforcing the law, and therefore impliedly adopts the interpretation upon re-enactment. In Philippine Bank of Communications v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, the Court held that administrative decisions Words used in the statute takes precedence over any other modes of construction. Thus, the ordinary or plain meaning of construction should control its interpretation. Textualists focus on the text of the legal provision, as it is presumed that the words, grammar, and punctuation communicate its meaning. Their main objective is to find the “public meaning” of the statute or the meaning of legal text as ordinary people understand it. Extrinsic sources of construction are avoided unless intrinsic sources of meaning are found to be insufficient. Modern textualists also refer to extrinsic sources as a means to confirm and verify the plain meaning to interpretation. Weakness: Words often do not mean the same to everyone. There is false belief that language has intrinsic meaning. Language evolve, and the meaning of words evolves. 2. Intentionalism theory or originalism Focuses on legislative intent “in the belief that the policies and elected, representative body chose should govern society” It is the duty of the court to discern the intent of that representative body and interpret statutes to further that intent. Difference with textualism: It does not require the establishment of ambiguity before it can resort to extrinsic sources of construction, because the original intent of the framers of the law that should have primacy in the determination of its meaning. Greater emphasis is placed on the original intent of the drafters of the law and this requires a review of legislative history and legislative deliberations. Strength: Consistency with the objective of construction, as it requires the court to inquire into the original intent of the legislature who wrote the law. Weakness: The legislature consists of many (in the Philippines, hundreds) individuals coming from different backgrounds and with different motivations. Legislative determination may not be a reliable source of interpretation as it only serves as evidence of the intention of but a few members of Congress who actively participated in the deliberation of a law, and whose views may not be necessarily shared by the other members of congress. Complied by: Dania S. Alcoran Page 2 of 4 STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION From the book STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION: Concepts and Cases by Ricardo M. Pilares III It fails to reconcile between general legislative intent and specific legislative intent. The former refers to the general intention of congress in drafting a law as a while, while the latter refers to the specific intention of the legislature in writing a specific section or provision of the statute. In its extreme, it focuses on specific legislative intent which could be misleading in the sense that it fails to view the statute in the light of the general intention that the legislature intended in the statute as a whole. However, it is equally fundamental that the legislative intent must be determined from the language of the statute itself. This principle must be adhered to even though the court be convinced by extraneous circumstances that the Legislature intended to enact something very different from that which it did enact. An obscurity cannot be created to be cleared up by construction and hidden meanings at variance with the language ised cannot be sought out. To attempt to do so is a perilous undertaking, and is quite apt to lead to an amendment of a law by judicial construction. 3. Purposivism or Legal process theory Focuses on determining the problem that the legislature is seeking to address. Interpretation is made with a view to the public policy that the statute seeks to advance. An analysis of the Philippine Supreme Court decisions shows that we do not adopt a single, unitary theory of construction. While our Courts are moderate textualists in theory, in focusing on the plain meaning theory of construction, they are, on the other hand, intentionalists and purposivists in approach. This is evidenced by the fact that while the Court prioritizes the plain meaning rule as the objective manifestation of legislative intent, the Court has not hesitated to state that if the language of the statute is inconsistent with its spirit or ratio legis, then the latter should prevail. The fact that our legal system does not adopt a single theory of construction gives the Courts flexibility in advancing its interpretation of a statute. B. RELATED LEGAL PRINCIPLES 1. SEPARATION OF POWERS In Angara v. Electoral Commission, the Court described the relationship of the three branches of the government through the principles of separation of powers and checks and balances: The separation of powers is a fundamental principle in our system of government. It obtains not through express provision but by actual division in our Constitution. To depart from the meaning expressed by the words is to alter the statute, is to legislate not to interpret. LIBERAL CONSTRUCTION V. JUDICIAL LEGISLATION By liberal construction of statutes, courts from the language used, the subject matter, and the purposes of those framing them are able to find out their true meaning. There is a sharp distinction, however, between construction of this nature and the act of a court engrafting upon a law something that has been omitted which someone believes ought to have been embraced. The former is liberal construction and is a legitimate exercise of judicial power. The latter is judicial legislation forbidden by the tripartite division of powers among the three departments of government, the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. In Naational Marketing Corporation v. Tecson, et. al., the Court held that if public interest demands a reversion to the policy embodied in the Revised Administrative Code, this may be done through legislative process, not by judicial decree. Courts cannot, under the guise of interpretation, “speculate as to an intent and supply a meaning not found in the phraseology of the law” and “the courts cannot assume some purpose in no way expressed and then construe the statute to accomplish this supposed intention. The court stated in Corpuz v. People that the primordial duty of the Court is merely to apply the law in such a way that it shall not usurp legislative powers by judicial legislation and that in the course of such application or construction, it should not make or supervise legislation, or under the guise of interpretation, modify, revise, amend, distort, remodel, or rewrite the law, or give the law a construction which is repugnant to its terms. The Constitution has provided for an elaborate system of checks and balances to secure coordination in the workings of the various departments of the government. The Court should shy away from encroaching upon the primary function of a co-equal branch of the Government; otherwise, this would lead to an inexcusable breach of the doctrine of separation of powers by means of judicial legislation. In cases of conflict, the judicial department is the only constitutional organ which can be called upon to determine proper allocation of powers between the several departments and among the integral or constituent units thereof. 2. HEIRARCHY OF LAWS The Constitution is a definition of the powers of government. Who is to determine the nature, scope and extent of such powers? The Constitution itself has provided for the instrumentality of the judiciary as the rational way. And when the judiciary mediates to allocate constitutional boundaries, it does not assert any superiority over the other departments; it does not in reality nullify or invalidate an act of the legislature, but only asserts the solemn and sacred obligation assigned to it by the Constitution to determine conflicting claims of authority under the Constitution and to establish for the parties in an actual controversy the rights which that instrument secures and guarantees to them. This is in truth all that is involved in what is termed judicial supremacy which properly is the power of judicial review under the constitution. Even then, this power of judicial review is limited to actual cases and controversies to be exercised after full opportunity of argument by the parties, and limited further to the constitutional question raised or the very lis mota presented. Under the principle of separation of powers, the Constitution vests in the legislative branch of government the power to enact laws, the executive branch, the power to execute laws, and in the judicial branch, the power to interpret laws. As held in Endencia v. David, the interpretation and application of laws is vested in the judicial department of government. The principle of separation of powers likewise imposes a limitation to judicial power. The power of the courts is limited to the interpretation of the laws enacted by the legislature and not to legislate, which is vested exclusively in the legislative branch of government. ARTICLE 7 of the Civil Code provides: Art. 7. Laws are repealed only by subsequent ones, and their violation or non-observance shall not be excused by disuse, or custom or practice to the contrary. When the courts declared a law to be inconsistent with the Constitution, the former shall be void and the latter shall govern. Administrative or executive acts, orders and regulations shall be valid only when they are not contrary to the laws or the Constitution. Under the principle of hierarchy of laws, the Philippine Constitution is supreme over all laws, and as such, acts of Congress, executive agencies exercising quasi-judicial functions and local legislative bodies must be consistent with the Constitution. 3. STARE DECISIS The maxim stare decisis et non quieta movere (follow past precedents and do not disturb what has been settled) is embodied in Article 8 of the Civil Code which provides: Art. 8. Judicial decisions applying or interpreting the laws or the Constitution shall form a part of the legal system of the Philippines. Once a question of law has been examined and decided, it should be deemed settled and closed to further argument. This principle is one policy Complied by: Dania S. Alcoran Page 3 of 4 STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION From the book STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION: Concepts and Cases by Ricardo M. Pilares III grounded on the necessity for securing certainty and stability in judicial decisions. Legis interpretation legis vim obtinet or the interpretation placed upon the written law by a competent court has the force of law. The Supreme Court is described as having the last word on what the law is, as it is the final arbiter of any justiciable controversy. As such, lower courts are enjoined to follow the decisions of the Supreme Court. The doctrine of stare decisis embodies the legal maxim that a principle or rule of law which has been established by the decision of a court of controlling jurisdiction will be followed in other cases involving a similar situation. It is founded on the necessity for securing certainty and stability in the law and does not require identity of or privity of parties. From the wordings of Article 8 of the Civil Code, it is even said that such decisions assume the same authority as the statute itself and, until authoritatively abandoned, necessarily become, to the extent that they are applicable, the criteria which must control the actuations not only of those called upon to decide thereby but also of those in duty bound to enforce obedience thereto. Abandonment thereof must be based only on strong and compelling reasons, otherwise, the becoming virtue of predictability which is expected from this Court would be immeasurably affected and the public’s confidence in the stability of the solemn pronouncements diminished. For the doctrine of stare decisis to apply, the principle of law laid down by the Supreme Court in the precedent case must pertain to the main issue of the case and not merely obiter dictum. A dictum is an opinion of a judge which does not embody the resolution or determination of the court and made without argument, or full consideration of the point, not the proffered deliberate opinion of the judge himself. As such, mere dicta are not binding under the doctrine of stare decisis. The Supreme Court is not precluded from changing its mind and reversing a previous doctrine that is laid down. ARTICLE VIII, Section 4(3) of the Philippine Constitution states that “no doctrine or principle of law laid down by the Court in a decision rendered en banc or in a division may be modified or reversed except by the Court sitting en banc. How would other similar pending cases be decided in light of the doctrinal change vis-à-vis the principle of stare decisis? In Ting v. Ting, “the interpretation or construction of a law by courts constitutes a part of the law as of the date the statute is enacted” and that “it is only when a prior ruling of this Court is overruled, and a different view is adopted, that the new doctrine may have to be applied prospectively in favor of parties who have relied on the old doctrine and have acted in good faith, in accordance therewith under the familiar rule of lex prospicit, not respicit. Complied by: Dania S. Alcoran Page 4 of 4