National Geographic History Magazine: Magellan, Celts, Agrippina

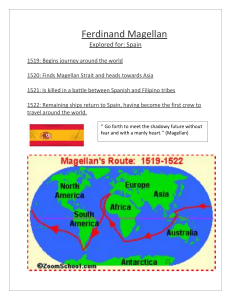

advertisement