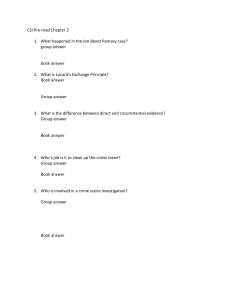

eBook Criminal Investigation 12e By Kären M. Hess, Christine Hess Orthmann, Henry Lim Cho

advertisement