'Oh Well You Know How Women Are' + 'Isn't That Just Like a Man'

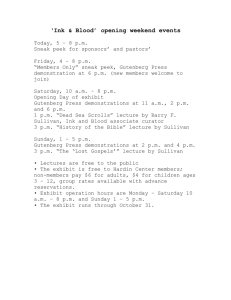

advertisement