CBT-I Manual

advertisement

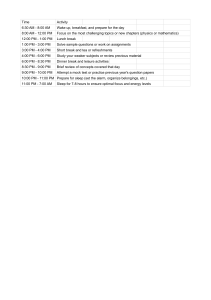

Rehab 3-Day Intensive Training: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) Evidence-based Insomnia Interventions for Trauma, Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain, TBI, Sleep Apnea and Nightmares Colleen E. Carney, Ph.D., Meg Danforth, Ph.D. WELCOME! Share your seminar selfie on our wall: Facebook.com/PESIinc. You may be in for a sweet surprise! Tweet us your seminar selfie @PESIinc, or tell us something interesting you’ve learned. Make sure to include #PESISeminar. Get free tips, techniques and tools at the PESI Blog: www.pesi.com/blog • www.pesirehab.com/blog • www.pesihealthcare.com/blog 3-Day Intensive Training: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) Evidence-based Insomnia Interventions for Trauma, Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain, TBI, Sleep Apnea and Nightmares Colleen E. Carney, Ph.D., Meg Danforth, Ph.D. Rehab ZNM053530 3/18 This manual was printed on 10% post consumer recycled paper Copyright © 2018 PESI, INC. PO Box 1000 3839 White Ave. Eau Claire, Wisconsin 54702 Printed in the United States PESI, Inc. strives to obtain knowledgeable authors and faculty for its publications and seminars. The clinical recommendations contained herein are the result of extensive author research and review. Obviously, any recommendations for client care must be held up against individual circumstances at hand. To the best of our knowledge any recommendations included by the author reflect currently accepted practice. However, these recommendations cannot be considered universal and complete. The authors and publisher repudiate any responsibility for unfavorable effects that result from information, recommendations, undetected omissions or errors. Professionals using this publication should research other original sources of authority as well. All members of the PESI, Inc. CME Planning Committee have provided disclosure of financial relationships with commercial interests prior to planning content of this activity. None of the committee members had relationships to report PESI, Inc. offers continuing education programs and products under the brand names PESI HealthCare, CMI Education Institute, Premier Education Solutions, PESI, MEDS-PDN, HeathEd and Ed4Nurses. For questions or to place an order, please visit: www. pesi.com or call our customer service department at: (800) 844-8260. 102pp 3/18 Rehab MATERIALS PROVIDED BY Colleen E. Carney, Ph.D., has been solving sleep issues for the past 15+ years. She is a leading expert in psychological treatments for insomnia, particularly in the context of co-occurring mental health issues. Dr. Carney is the director of the Sleep and Depression Laboratory at the Department of Psychology at Ryerson University. Her work has been featured in The New York Times and she has over 100 publications on insomnia. She frequently trains students and mental health providers in CBT for insomnia at invited workshops throughout North America and at international conferences. Dr. Carney is a passionate advocate for improving the availability of treatment for those with insomnia and other health problems. Speaker Disclosures: Financial: Colleen Carney is a professor at Ryerson University. She receives a speaking honorarium from PESI, Inc. Non-financial: Colleen Carney is a member of the Canadian Psychological Association; and the Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT). Meg Danforth, Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist and certified behavioral sleep medicine specialist who has been helping people sleep better without medication for the past 15 years. She is a clinician and educator at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. As the director of the Duke Behavioral Sleep Medicine Clinic, she provides advanced clinical care to patients with sleep disorders and comorbid medical and mental health issues. She also provides clinical training and supervision to psychology graduate students, interns, and fellows. Dr. Danforth is committed to teaching clinicians from a variety of backgrounds to deliver CBT-I in the settings in which they practice. Her work has been featured in the Associated Press and CBS News. Speaker Disclosures: Financial: Margaret Marion Danforth is a clinical associate at Duke University Medical Center. She receives a speaking honorarium from PESI, Inc. Non-financial: Margaret Marion Danforth is a member of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Materials that are included in this course may include interventions and modalities that are beyond the authorized practice of mental health professionals. As a licensed professional, you are responsible for reviewing the scope of practice, including activities that are defined in law as beyond the boundaries of practice in accordance with and in compliance with your professions standards. CBT-I: Evidence-based insomnia interventions forTrauma, Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain,TBI, Sleep Apnea, and Nightmares Colleen Carney, Ph.D. Ryerson University Meg Danforth, Ph.D. CBSM Duke University Medical Center Time Topics 8:00-10:00 Welcome Assessment Sleep and Its Regulation 10:00-10:15 Break 10:15-12:00 Step-by-Step Guide to CBT-I: Stimulus Control and Sleep Restriction Therapies 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-2:30 Step-by-Step Guide to CBT-I: Cognitive Therapy and Counterarousal 2:30-2:45 Break 2:45-4:00 Implementation Issues 1 2 *Most CBT trials focus on these types of complaints. There is some controversy with quantitative criteria (e.g., Lineberger, Carney, Edinger, & Means, 2006) 3 Electrical Movement Experience Prospective Prospective Prospective Objective Objective Dubious validity in insomnia (Littner et al., 2003) Dubious validity in insomnia (Chambers, 1994) Insomnia is a subjective disorder Essential tool (Buysse et al., 2006) (Johns, 1991) See Buysse et al., 2006 for discussion 4 Treating insomnia with untreated apnea is ineffective and unsafe Chung et al. (2008) • Snore • (Not really tiredness) Sleepiness • Observed apneas • High Blood Pressure • BMI over 35 kg/m2? • Age: Older than 50 years old? • Neck size larger than 43 cm (17”+)? • Gender: Male? Yes to 2 or more → referral to sleep clinic www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php 8pm 11pm 2am 6am 10am Conventional Sleep Phase Delayed Sleep Phase Advanced Sleep Phase 5 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 1:30 am 12:30 am 11:00 pm 1:00 am 2:00 am 11:15 pm 120 min 90 min 50 min 35 min 60 min 60 min 120 min 10 min 15 min 5 min 15 min 5 min 5 min 15 min Wake time 6 am 6:15 am 6:10 am 6 am 6:05 am 8:00 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:50 am 8:30 am 7:45 am 6:15 am 7:45 am 10:45 am 10:30 am Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12:00 am 1:30 am 12:30 am 12:00 am 2:30 am 3:00 am 12:30 am 180 min 90 min 150 min 170 min 35 min 5 min 120 min 10 min 15 min 5 min 10 min 5 min 5 min 15 min Wake time 8 am 8 am 8 am 8 am 8 am 2 pm 2:30 pm Rise time 8:30 am 8:45 am 8:30 am 9 am 8:45 am 2:15 pm 2:40 pm Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night 6 7 (See Borbely et al., 2016) determines the amount and quality of sleep Sleep 9am 3pm 9pm 3am 9am Sleep 8 determines the timing of sleep and wakefulness M Wake 9am 3pm 9pm 3am 9am Sleep • Timing • Clock determines timing of sleep especially REM sleep timing AND timing of alertness • Managing Drift • There is drift in our clock because it is longer than 24 hours • Regular bedtimes, regular rise times and regular light exposure “set” the clock and manage drift 9 We need to keep a schedule or we will suffer from “social jetlag” 10 Increased Physiological (Hyper)arousal in Insomnia Physiological Hyperarousal on Multiple Sleep Latency Test Propensity to nap ↓ ↓ ↑ ↑ “Tired but wired” (Bonnet et al., 2014) Do wakeful activities in bed – train yourself to be awake Consider also: hot flashes, pain, nightmares, panic . . . Ask about “the switch” 11 Precipitating factor(s) Coping with the sleep disruption Homeostatic Disruption Reduced sleep drive Circadian Disruption Improper Sleep Scheduling Arousal Cognitive Poor sleep habits Conditioned arousal Chronic Insomnia (Spielman, 1987; Webb, 1988) 12 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 11:05 pm 10:35 pm 10:55 pm 12:15 am 10:15 pm Time to fall asleep 25 20 40 60 35 15 95 Time awake during night 20 25 15 35 20 45 60 Wake time 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 8:40 am 7:50 am 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 11:45 am Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 12:30 am 1:05 am 10:35 pm 12:55 am 2:15 am 10:15 pm Time to fall asleep 25 20 40 60 35 15 95 Time awake during night 20 25 15 35 20 45 60 Wake time 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 11:45 am Bedtime Rise time Bedtime Rise time Friday 13 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 9:30 pm 11:00 pm 10:35 pm 9:15 pm 12:00 am 10:30 pm 100 min 50 min 60 min 120 min 45 min 55 min 90 min 5 min 15 min 15 min 10 min 15 min 15 min 20 min Wake time 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 8:45 am Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Treatment # of Studies Classification Stimulus Control 6 Well-established Relaxation Therapies 8 Well-established Paradoxical Intention 3 Well-established Sleep Restriction Therapy 3 Well-established CBT (no relaxation) 6 Well-Established CBT + relaxation 6 Well-Established EMG Biofeedback 4 Probably efficacious Other Multi-component 3 Probably efficacious Cognitive Therapy 0 Not supported Sleep Hygiene Education 3 Not supported (Morin et al., 2006) Perpetuating Factors and CBT-I Cognitive Therapy / Counter-Arousal Relaxation / mindfulness Homeostatic Disruption Reduced sleep drive Sleep Restriction Circadian Disruption Improper/irregular Sleep Scheduling Stimulus Control Chronic Insomnia (Adapted from Webb, 1988) Arousal Cognitive Poor sleep habits Conditioned arousal Sleep Hygiene 14 Stimulus Control Therapy: The Bed-Sleep Connection (Bootzin, 1972) Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 9:30 pm 11:00 pm 10:35 pm 9:15 pm 12:00 am 10:30 pm 35 min 25 min 15 min 20 min 25 min 15 min 30 min 100 min 50 min 60 min 120 min 45 min 55 min 90 min Wake time 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 8:45 am Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night 3 naps attempted this week 15 Activity Likelihood that it would prevent sleepiness from occurring Result of the Experiment Watch series on Netflix 50/50 Seemed ok. Went back to bed 40 minutes later Catch up on social media 60% Too interesting. Stopped after 2 hours Listen to jazz 10% Worked well. Fun and I got sleepy quickly Adapted from Quiet Your Mind and Get to Sleep (Carney & Manber, 2009) “I can’t get up at the designated rise time!” Find out why. Difficulty Action Plan Rationale not compelling/understood Review multiple times, check-in, handouts Comfort Consider a transition plan to address comfort Anhedonia Contingencies: Plan activities (that involve commitment to others); elicit help from significant others Alarm Use multiple, staggered alarm clocks; elicit help from others Eveningness Morning light sets the clock and increases alertness 16 *Sleep Efficiency (SE) is the percent of time asleep relative to the time spent in bed Sleep Restriction Therapy (SRT) or Time-in-Bed Restriction In general, we do not prescribe less than 5.5 hours time-in-bed. (Spielman et al., 1987) 17 Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 10:00 pm 9:30 pm 8:30 pm 9:45 pm 8:45 pm 8:30 pm Sunday 9:30 pm 45 min 60 min 90 min 45 min 120 min 90 min 60 min M Time in bed (TIB) = 9.85 hours M Total sleep time (TST) = 7.75 hours 0 min 15 min 30 min 0 min 0 min 60 min 45 min Wake time 6:15 am 6:15 am 6:30 am 6:15 am 6:30 am 7:00 am 7:30 am Rise time 6:30 am 6:30 am 7:00 am 6:30 am 7:00 am 8:30 am 8:00 am TIB 8:30 9:00 10:00 8:45 10:15 12:00 10:30 TST 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:45 7:45 8:00 8:45 Sleep opportunity window should consider Eveningness/morningness tendency Life constraints (e.g., work schedule) Collaborate to determine out-of-bed (rise) time Instruct to get out of bed shortly after waking Determine bedtime based on time-in-bed and rise time Count back from rise time Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Example: Time in bed=6 hours Rise time= 6AM Bedtime =12AM Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday 10:00 pm 9:30 pm 10:00 pm 9:45 pm Friday 10:30 pm Saturday 11:00 pm Sunday 9:30 pm 90 min 120 min 90 min 45 min 120 min 30 min 120 min M Time in bed (TIB) = 9 hours M Total sleep time (TST) = 6 hours 60 min 90 min 30 min 90 min 0 min 0 min 30 min Wake time 6:30 am 5:30 am 6:00 am 6:15 am 6:15 am 7:00 am 6:00 am Rise time 7:00 am 7:00 am 7:00 am 7:15 am 6:30 am 8:00 am 6:30 am TIB 9:00 9:30 9:00 9:30 8:00 9:00 9:00 TST 6:00 4:30 6:00 6:15 5:45 7:30 6:00 18 *“I can’t stay up that late. I’m too sleepy!” Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Saturday Sunday 12:00 am 12:30 am 12:30 am 12:00 am 12:30 am 1:30 am 12:15 am 15 min 25 min 20 min 25 min 25 min 20 min 20 min 10 min 15 min 5 min 10 min 5 min 5 min 15 min Wake time 6:15 am 6:15 am 6:35 am 6:15 am 6:35 am 8:00 am 7:30 am Rise time 6:30 am 6:40 am 7:00 am 6:25 am 7:05 am 8:30 am 8:00 am 6:10 82% 6:30 87% 6:25 88% 7:00 87% 7:45 86% Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night TIB SE% 6:30 90% Friday 6:35 85% 19 Remember: Sleep Hygiene education is not an evidence-based treatment for insomnia! 20 21 Concern Solutions I have to get the car serviced 1. After this exercise I can look at the calendar to see when I can do this 2. I can ask my spouse if they have time Reproduced from Overcoming Insomnia: A Cognitive Behavioral Approach (Edinger & Carney, 2015) Excessive mentation: Rumination RCA: Rumination Cues Action! (Addis & Martell, 2004) 22 Cultivate a practice, not a mindfulness pill! 23 Consequences Defective • There is something wrong with me Helpless • There is nothing I can do about it And I need to exert effort to fix it (Espie et al., 2006) Subsequent anxiety about failed attempts to fix it (Beck, 1999) Situation Coming back to the office from my lunch break and noticed how tired I was Mood (Intensity 0-100%) Tired (100%) Upset (100%) Worried (80%) Thoughts I’m going to get sick if I keep going like this I can’t keep going on like this Something really terrible is going to happen if this doesn’t get resolved. I could get fired and eventually become homeless Evidence for the thought Evidence against the thought Adaptive/Coping statement I’m not exercising any longer I usually start to feel a little better later in the afternoon Although I tend to feel lousy at different times during the day, the reality is that I always make it through and nothing bad has ever happened as a result of the insomnia I don’t feel like doing things I got into trouble for coming to work late last month. 99.9% of the time I am on-time and have no problems at work My sleep problems have been going on for years and nothing bad has happened Do you feel any differently? Tired (90%) Upset (50%) Worried (45%) My job is secure—I am not going to be fired (Padesky, 1993) 24 Behavioral Experiments Belief Alternative? Experiment I have a limited store of energy Conserving energy may increase fatigue Expend versus conserve Poor sleep is dangerous I may be able to cope reasonably after poor sleep Restrict sleep and monitor coping I can’t control sleep because my mind is too active Perhaps because there isn't time to process the day? Constructive worry in evenings versus status quo Being tired makes me look bad Perhaps others are not particularly attuned to this Took series of photos and tested people’s ratings Monitoring how I feel helps me to keep track, in case I have to make an adjustment Monitoring increases the likelihood that you will perceive minor changes in energy Monitor external stimuli and mood for two hours and then internal stimuli for 2 hours I need to nap to get through the day If I don’t nap, my nighttime sleep will improve, and I can cope Monitor napping, tiredness and coping for one week of naps and one week without (Ree & Harvey, 2004) (Harvey & Talbot, 2010) 25 Explore what contributes to how one feels during the day Paradoxical Intention 26 Combined SRT/ Stimulus Control: One-session CBT-I (e.g., Buysse et al., 2011) Week 1 Psychoeducation, Stimulus Control, Sleep Restriction Therapy, Sleep Hygiene (if needed), Buffer zone Week 2 Week 3 At-home implementation Troubleshoot adherence, determine if changes necessary to schedule, add counterarousal and cognitive therapy Week 4 Week 5 At-home implementation Troubleshoot adherence, determine if changes necessary to schedule, continue with cognitive therapy, introduce termination issues, relapse prevention homework Week 6 Week 7 At-home implementation Troubleshoot adherence, determine if changes necessary to schedule, cognitive therapy, termination issues and relapse prevention (Edinger & Carney, 2015) 27 28 29 (Qaseem et al., 2016) 30 Sateia et al., 2017 A WEAK* recommendation reflects a lower degree of certainty in the outcome 31 More on this tomorrow! 32 CBT-I: Evidence-based insomnia interventions forTrauma, Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain,TBI, Sleep Apnea, and Nightmares Colleen Carney, Ph.D. Ryerson University Meg Danforth, Ph.D. CBSM Duke University Medical Center Time Topics 8:00-10:00 Welcome Review/Bridging 10:00-10:15 Break 10:15-12:00 Depression and Anxiety 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-2:30 Trauma and TBI 2:30-2:45 Break 2:45-4:00 Chronic Pain Hypnotic Discontinuation Precipitating factor(s) Coping with the sleep disruption Homeostatic Disruption Reduced sleep drive Circadian Disruption Improper Sleep Scheduling Chronic Insomnia (Spielman, 1987; Webb, 1988) Arousal Cognitive Poor sleep habits Conditioned arousal Go to bed early Drink alcohol Worry about sleep problem Try to sleep-in Try to nap… 33 Session One/One session handout Sleep Rules 6:00 AM 11:30 PM Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Bedtime 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 11:15 pm 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 1:15 am 11:00 pm Time to fall asleep 25 min 10 min 35 min 20 min 35 min 5 min 20 min 60 min 45min 90 min 75 min 30 min 15 min 60 min Wake time 7 am 7:15 am 6 :45 am 6:50 am 7 am 8:40 am 9:20 am Rise time 8:15 am 8:20 am 7:50 am 8:30 am 8:15 am 10:50 am 10:45 am TIB 9:15 8:50 9:35 11:45 Time awake during night 8:35 9:30 7:45 34 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 9:30 pm 11:00 pm 10:35 pm 9:15 pm 12:00 am 10:30 pm 35 min 25 min 15 min 20 min 25 min 15 min 30 min 100 min 50 min 60 min 120 min 45 min 55 min 90 min Wake time 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 8:45 am Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Friday Average total sleep time for the 2 weeks is 6.5 hours Unaltered* CBT-I is efficacious 35 Perpetuating Factors in Comorbid Insomnia Kohn & Espie, 2005 Carney, Edinger, Manber, et al., 2007 PI=MDD-I DBAS Cognitive Factors PI=CI sleep effort beliefs Unhelpful Beliefs Worry & intrusive thoughts Kohn & Espie, 2005 PI=CI variability Homeostatic Disruption Excessive nocturnal TIB Daytime Napping Circadian Disruption Improper Sleep Scheduling Kohn & Espie, 2005 PI=CI excessive TIB Chronic Insomnia Inhibitory Factors Poor sleep hygiene Conditioned arousal Kohn & Espie, 2005 PI=CI arousal 36 Combinations of sleep and insomnia treatments Remember it is 37% in STAR*D SSRI SLEEP MED SSRI 37 Compensatory Etiological Model STRESS Shared vulnerability (e.g., neurochemical sensitivity, beliefs, ruminative tendency ∆ in chemical activity, life event, illness Disrupted sleep Comorbid condition Coping (↑safety bx and ↑ effort) Circadian, homeostatic dysregulation, arousal I N S O M N I A Edinger, Means, Carney & Manber (2011) Selected evidence for unaltered CBT-I in MDD Case Study: Comorbid Insomnia and Depression 38 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Saturday Sunday 9:00 pm 11:30 pm 11:05 pm 10:35 pm 10:55 pm 11:15 pm 11:15 pm 25 20 40 60 35 15 95 20 25 15 35 20 45 60 Wake time 8:30 am 7:30 am 7 :30 am 7:15 am 7:20 am 8:40 am 8:50 am Rise time 9:15 am 8:20 am 8:15 am 8:25 am 7:35 am 8:50 am 11:45 am Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Friday Average Time in Bed = 10 hours Average Total Sleep Time = 7.93 hours “I don’t feel like getting up.” PLAN OUTSIDE → IN ACTION CONTINGENCIES INSIDE → OUT WAIT FOR MOTIVATION ACTION LESS LIKELY Martell, Dimidjian, & Herman-Dunn (2010) 39 Coping Card • “I will get up by 7:30 AM every day this week.” Plan • I know this will help improve my sleep. • I will go the coffee shop around the corner and read the paper. I enjoy doing this. • I will meet with Joe at the Gym at 8:00 AM on Mondays and Wednesdays. Contingencies • It is hard, but I have to do it if I want to sleep better. • I can handle getting out of bed at 7:30 AM. Troubleshooting Dan’s Rising Adherence Problems Mood worsening? 7 am MON TUES WED THURS FRI SAT SUN SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP 8 am SLEEP IN BED 8 IN BED 7 IN BED 8 CAFÉ 2 SLEEP SLEEP 9 am IN BED 7 LAPTOP 8 GYM 3 LAPTOP 8 WALK 3 SHOWER 5 IN BED 8 10 am SHOWER 5 LAPTOP 8 BRFT 6 PHONE 5 SHOP 3 IN BED 8 IN BED 8 11 am BRFT 7 TV 8 GAMING 6 SHOWER 4 BILLS 5 TV IN BED 8 READING 8 12 pm SCHOOL 5 SCHOOL 5 GAMING 7 SCHOOL 5 SHOWER 4 GAMING 7 SHOWER 6 1 pm SCHOOL 5 SCHOOL 5 GAMING 7 SCHOOL 5 LUNCH 5 GAMING 6 BRFT 7 2 pm SCHOOL 5 SCHOOL 5 GAMING 7 SCHOOL 5 TV 8 GAMING 7 NAP 7 3 pm SCHOOL 5 LAPTOP 8 GAMING 7 SCHOOL 5 COUCH 8 LAPTOP 8 NAP 4 pm NAP 7 LAPTOP 8 SHOWER 6 LAPTOP 8 COUCH 8 LAPTOP 8 LAPTOP 8 5 pm READING 5 LAPTOP 8 READING 6 LAPTOP 8 READING 7 LAPTOP 8 LAPTOP 8 6 pm COOK 4 GAMING 7 GAMING 7 GAMING GAMING 8 LAPTOP 8 DINNER 4 7 pm DINNER 5 GAMING 8 NAP 6 GAMING GAMING 8 GAMING 7 GAMING 5 8 pm GAMING 8 DINNER 4 DINNER 5 DINNER 4 DINNER 5 READING 6 PHONE 3 9 pm IN BED 7 GAMING 7 GAMING 6 GAMING 6 GAMING 7 GAMING 7 GAMING 6 READING 8 10 pm IN BED 6 TV 7 LAPTOP 6 IN BED 7 GAMING 7 DINNER 7 11 pm TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 8 IN BED 8 IN BED 7 12 am TV IN BED 9 TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 7 TV IN BED 6 TV IN BED 7 TV IN BED 8 IN BED 8 1 am SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP SLEEP TV IN BED 8 SLEEP SLEEP 40 FEELING THOUGHT sluggish MOST LIKELY THOUGHT: THOUGHTS ABOUT FATIGUE OR THE WEATHER? BEHAVIOR MOST LIKELY BEHAVIOR: ACTION OR INACTION? OUTCOME MOST LIKELY OUTCOME WITH ACTION? INACTION? Behavioral experiment: test same trigger (mood) but an alternative behavioral coping response. Does it result in a different, more desired outcome? Sleep/the Bed as an escape 41 Peripheral, afferent nerves or lower motor neuron issue Peripheral fatigue Fatigue experience Resting/ avoidance Central fatigue Decreased motivation due to perceived imbalance Chaudhuri & Behan (2004) 42 Bedtime Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 11:15 pm 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 1:15 am 11:00 pm No sleep No sleep No sleep No sleep No sleep No sleep No sleep 8:15 am 8:20 am 7:50 am 8:30 am 8:15 am 10:50 am 10:45 am Friday Saturday Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Wake time Rise time 6 hour sleep sleepneed sleep6 hour sleep need Hours spent in bed Monday Tuesday 11:00 pm 11:30 pm 11:05 25 20 20 Wake time Rise time Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Wednesday pm Thursday Sunday 10:35 pm 10:55 pm 12:15 am 10:15 pm 40 60 35 15 95 25 15 35 20 45 60 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 8:40 am 7:50 am 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 11:45 am 43 p < .001 p = .392 Significant group effect MANOVA (p < .001) p = .003 Carney, Harris & Edinger, 2009 (e.g., Lichstein et al., 2001; Riedel, Lichstein & Dwyer, 1995) 44 (Davies, Lacks, Storandt,& Bertelson, 1986) High sleep-anxiety High arousal in bed Stimulus Control May need countercontrol instead of strict Stimulus Control Use Stimulus Control and emphasize counterarousal Sleep Restriction Therapy May need sleep Use SRT and emphasize compression instead counter-arousal of SRT Cognitive therapy 45 Insomnia vs. PTSD targets Common Targets Insomnia only PTSD + insomnia Erratic sleep scheduling Daytime napping Alcohol to aid sleep Hyper-arousal as bedtime approaches Unhelpful beliefs about sleep-conducive habits/needs Excessive time in bed* Sleep avoidance – limiting time in bed at night Using bed for non-sleep activities* Hypervigilance during sleep – on guard/checking Unhelpful beliefs that raise anxiety about sleep loss* Unhelpful beliefs that raise anxiety about being asleep 46 47 48 Chronic pain 11-55% 39-75% Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) 50-88% Insomnia 1020% 4-20% 49 (Davies, Lacks, Storandt, & Bertelson, 1986; Hoelscher & Edinger, 1988) Class Effect of pain relievers on sleep architecture N1 and N2 SWS REMS NSAIDs TCAs (amitryptaline) ↑ Variable SNRIs (duloxetine) - ↓ ↑ - Anticonvulsants (gabapentin) Antispasmotics (baclofen) ↓ ↑ ↓ - ↑ - ↑ Opioids* ↓ ↓ ↓ Cairnes (2007) 50 51 Good = improved sleep + improved daytime function + able to cope with sleep problem Reasonable = improvement in at least 1 of these 3 areas No Change = no perceived improvement 52 • “CBT-I works whether you are on or off medications, so what would you like to do?” SUSTAINED RECOVERY SLEEP SYSTEM BASELINE MED USE DISSASTISFIED WITH SLEEP OR PILLS CBT-I SLEEP IMPROVEMENT PILLS? 53 CLASSICAL CONDITIONING OF PILL TAKING 54 Safety behavior What message are you sending yourself by engaging in this behavior? What will you do to show that it is not true? Result of the experiment I take a sleeping pill in the middle of the night when I notice I am “worked-up.” That I have lost all confidence in my ability to sleep. I’ll refrain from taking the pill in the middle of the night and see what happens. I felt less groggy on days in which I didn’t take the pill It was initially frightening but I noticed that I fell back to sleep only a few minutes sooner if I took the pill That I don’t think I can cope with feeling “worked-up” Reproduced from Quiet Your Mind and Get to Sleep: Solutions for Insomnia in those with Depression, Anxiety or Chronic Pain (Carney & Manber, 2009) Mood (Intensity 0-100%) Worried (80%) Thoughts I can’t keep going on like this I’ve got to take a pill I’m never going to get through I’ll never get today to sleep I’m if I going don’t to mess take a pillup I need to get some sleep I can’t concentrate Evidence for the thought Evidence against the thought Do you feel any differently? When I take a pill I eventually fall asleep Eventually I would fall asleep anyway Worried (50%) When I run out of pills, it’s not like I don’t sleep at all I feel crappy the next day after taking a pill anyway Adapted from: Overcoming Insomnia (Edinger & Carney, 2008) 55 Cognitive Therapy Review Evidence From Sleep Diary Martell, Dimidjian, & Herman-Dunn (2010) TRAP TRIGGER RESPONSE AVOIDANCE PATTERN OUTCOME DELAY IN FALLING ASLEEP ANXIETY TAKE PILL DAYTIME SYMPTOMS TRIGGER RESPONSE ALTERNATIVE COPING OUTCOME DELAY IN FALLING ASLEEP ANXIETY REGROUP ON THE COUCH TRAC ? GATHER DATA 56 57 CBT‐I: Evidence‐based insomnia interventions forTrauma, Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain,TBI, Sleep Apnea, and Nightmares Colleen Carney, Ph.D. Ryerson University Meg Danforth, Ph.D. CBSM Duke University Medical Center Time Topics 8:00‐10:00 Welcome Working effectively with those with sleep apnea 10:00‐10:15 Break 10:15‐12:00 Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for Nightmares 12:00‐1:00 Lunch 1:00‐2:30 Case Formulation 2:30‐2:45 Break 2:45‐4:00 Case Exercises and Remaining Issues 58 59 60 Physical Comfort Mechanical Problems Social Factors Psychological Factors 61 Recognizing Stages of Change (Prochaska & Norcross, 2002) 62 63 64 65 *Some cases are so severe a mental health professional is needed 66 67 8pm 2am 11pm 6am 10am Conventional Sleep Phase COMPLAINT? Delayed Sleep Phase Advanced Sleep Phase COMPLAINT? Wake Sleeping here? Alerting signals 9am 3pm Wake Melatonin secreted 9pm 3am 9am Sleep 68 Morgenthaler et al., 2007 Morgenthaler et al., 2007 69 7:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 11:00 AM 12:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:00 PM 4:00 PM 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9:00 PM 10:00 PM 11:00 PM 12:00 AM 1:00 AM 2:00 AM 3:00 AM 4:00 AM 5:00 AM 6:00 AM Strength of Alerting Signal 7:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 11:00 AM 12:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:00 PM 4:00 PM 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9:00 PM 10:00 PM 11:00 PM 12:00 AM 1:00 AM 2:00 AM 3:00 AM 4:00 AM 5:00 AM 6:00 AM Strength of Alerting Signal Morgenthaler et al., 2007 Wake Light or activity here advances the clock; ↑alertness Rest Time Leveraging the circadian system Wake Light here ↑alertness Rest Light here ↑alertness Light here may delay the clock Time 70 SCHEDULE MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY WORK SHIFT 15:00-23:00 15:00-23:00 15:00-23:00 OFF 07:00-15:00 07:00-15:00 07:00-15:00 CURRENT 24:00-08:30 25:00-08:30 01:00-09:30 01:00-10:30 23:00-06:00 22:30-06:15 22:00-05:45 PROPOSED 24:00-07:00 24:00-07:00 24:00-07:00 23:30-07:00 23:00-06:00 23:00-06:00 23:00-06:00 USE NAPS IF NEEDED USE LIGHT, MOVEMENT IN A.M. Imagery rehearsal training for nightmares Nightmares 71 Differential diagnosis: Nightmares We don’t use PSG except to rule out: breathing disorders, seizure disorder, narcolepsy, RBD 72 Casement & Swanson, 2012 73 Treating Nightmares: Imagery Rescripting and Rehearsal 74 75 76 77 Imagery Rescripting and Rehearsal Summary 78 From: Manber, R. & Carney, C.E. (2015). Treatment Plans and Interventions: Insomnia. A Case Formulation Approach. Domains 1. Sleep Drive: Are there any factors weakening the sleep drive? Targets Excessive time‐in‐bed in relation to the average total sleep time? Dozing? Napping? Substances that block sleep? Decreased physical activity in a 24‐ hour period? Lingering in bed greater than 30 minutes post‐wake in the morning? Manber & Carney, 2015 79 Assessing low sleep drive on Sleep Log Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Monday Tuesday 11:00 pm 11:30 pm Wednesday 11:05 pm Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 10:35 pm 10:55 pm 12:15 am 10:15 pm 25 20 40 60 35 15 95 Average total sleep time (ATST) = 7 hours; Average time in bed (TIB) over 9 hrs. 7.07 total sleep time / 9.33 time-in-bed = 78% Sleep Efficiency 20 25 15 35 20 45 60 Wake time 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 7 am 8:40 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 11:45 am 80 *Actually a treatment to address conditioned arousal, so we will revisit Bootzin, 1972 Domains Targets 1. Sleep Drive: Are there any factors weakening the sleep drive? √ Excessive time‐in‐bed in relation to the average total sleep time? Dozing? Napping? √ Substances that block sleep? √ Decreased physical activity in a 24‐ hour period? √ Lingering in bed greater than 30 minutes post‐wake in the morning? Manber & Carney, 2015 (Fredholm, Yang, & Wang, 2017) • Caffeine – timing and reduction • Nicotine reduction/elimination • Prescribed exercise ‐ timing • Light bedtime snack (milk, peanut butter) • Avoid middle of the night eating • Reduce alcohol & other substances • Optimize environment: light, noise, temperature 81 Domains 2. Biological clock: Are there factors weakening the signal from the biological clock? Targets An hour or more variability in rise time An hour or more variability in bedtime Are they a night owl keeping an early bird’s schedule, or reverse? Manber & Carney, 2015 Finding clock irregularity in diaries Monday Tuesday Wednesday 11:00 pm 12:30 am 1:05 Time to fall asleep 25 20 40 Time awake during night 20 25 Wake time 6 am 7:15 am Bedtime Rise time Saturday Sunday 10:35 pm 12:55 am 2:15 am 10:15 pm 60 35 15 95 15 35 20 45 60 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 11:45 am am Thursday Friday JETLAG Domains 2. Biological clock: Are there factors weakening the signal from the biological clock? Targets √ An hour or more variability in rise time √ An hour or more variability in bedtime Are they a night owl keeping an early bird’s schedule, or reverse? Manber & Carney, 2015 82 Domains Targets √ Rituals to produce sleep even when sleep continues 3. Arousal: Any to be bad, e.g., no alarm clock, sleeping separate evidence of from bed partner, knockout shades, white noise hyperarousal? machine/masks, tv…? Any behaviors engaged to “produce sleep” (i.e., sleep effort)? Are they worried about sleep? √ Are they worried about other things (in bed)? Are they wide awake upon getting into bed? √ √ Do they stay in bed when awake? √ Do they feel frustrated/anxious/distressed while awake in bed? Manber & Carney, 2015 Bootzin, 1972 See any possible sleep effort behaviors? Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 11:00 pm 9:30 pm 11:00 pm 10:35 pm 9:15 pm 12:00 am 10:30 pm 35 min 25 min 15 min 20 min 25 min 15 min 30 min 100 min 50 min 60 min 120 min 45 min 55 min 90 min Wake time 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 6 am 8:40 am 7:50 am Rise time 7:15 am 7:20 am 7 am 7:25 am 7:15 am 10:50 am 8:45 am TIB 7:15 10:50 8:00 7:50 10:00 10:50 10:15 Bedtime Time to fall asleep Time awake during night Note: 3 daytime naps attempted 83 Domains Targets √ Rituals to produce sleep even when sleep continues 3. Arousal: Any to be bad, e.g., no alarm clock, sleeping separate evidence of from bed partner, knockout shades, white noise hyperarousal? machine/masks, tv…? Any behaviors engaged to “produce sleep” (i.e., sleep effort)? Are they worried about sleep? √ Are they worried about other things (in bed)? Are they wide awake upon getting into bed? √ √ Do they stay in bed when awake? √ Do they feel frustrated/anxious/distressed while awake in bed? Manber & Carney, 2015 Case Formulation Form: Unhelpful sleep behaviors? Domains Targets √ Excessive or late caffeine? 4. Unhealthy √ Alcohol? sleep behaviors: Any sleep Marijuana? √ Short‐acting sleeping pills? behaviors that interfere with Nocturnal eating? sleep Vigorous evening exercise? depth/continuity ? Manber & Carney, 2015 84 Case Conceptualization: Medications that Impact Sleep 85 Rule for CBT‐I: Noncontingency “CBT‐I works whether you are on or off medications, so what would you like to do?” SUSTAINED RECOVERY SLEEP SYSTEM BASELINE MED USE CBT-I SLEEP IMPROVEMENT DISSASTISFIED WITH SLEEP OR PILLS PILLS? Case Formulation Form: Unhelpful sleep behaviors? Domains Targets √ Excessive or late caffeine? 4. Unhealthy √ Alcohol? sleep behaviors: Any sleep Marijuana? √ Short‐acting sleeping pills? behaviors that interfere with Nocturnal eating? sleep Vigorous evening exercise? depth/continuity ? Manber & Carney, 2015 Domains 6. Comorbidities: Any co‐occurring conditions that impact sleep? Targets Sleep apnea, if yes, is it adequately treated? Restless Leg Syndrome, if yes, is it adequately treated? Periodic Limb Movement, if yes, is it adequately treated? Chronic pain, if yes, is it adequately treated? √ PTSD √ Others? Manber & Carney, 2015 86 Case Conceptualization Comorbidities What comorbidities affect client’s presentation and how? Concurrent/integrated or Successive? • CBT‐I takes 8 weeks (4 biweekly individual sessions or 7 sessions for group) – doable but… • What if you only have 12 sessions allowable? • What if sleep is as important as pain, panic…? • What if your case formulation suggests their problems are all interrelated? Sequential versus integration • No real empirical guidance • Considerations • Primacy of sleep goals – Don’t put CBT‐I on your list just because they meet criteria: low stage of readiness • Complementary techniques and targets allows you to strengthen rationale/buy‐in 87 Pain Cycle Psychoeducation Disuse (2◦ pain, deconditioning) Disability Plan: Present model, psychoeducation, goal setting, exercise and paced ↑ activities, relaxation training, challenge catastrophizing Monitoring for aversive sensations Decreased Use Increased Resting Re-injury fear; poor performance under pain conditions Event Low back injury Pain, distress Threatening ..about pain Insomnia Cycle Psychoeducation Event Increased insomnia Calling in sick Plan: Present model, psychoeducation, goal setting, stimulus control, ↑ day me ac vi es, ↓ me in bed, relaxation training, challenge catastrophizing Monitoring for fatigue/arousal sensations Alcohol Use Increased Resting Lost control of sleep; poor performance under insomnia conditions Bedridden during back injury Sleeplessness, fatigue, distress Threatening ..about insomnia Combined Psychoeducation Increased insomnia; increased 2◦ pain Calling in sick; depression Monitoring for pain/fatigue/arousal sensations Alcohol Use Increased Resting Cancelling Event Back injury and prolonged timein-bed Sleeplessness, fatigue, increased pain, distress Increase activities; decrease time-in-bed Lost control of sleep; poor performance under insomnia/fatigue/pain conditions; re-injury Test whether control/effort helps/hurts Threatening ..about sleep loss and pain Test whether this helps/hurts 88 Commonalities • Assessment • Orient to CBT • Present model through CBT lens • Monitoring • Challenge unhelpful thinking • Try new alternative coping behaviors (to replace avoidance) • Skills training (e.g., relaxation, problem solving) • Disorder specific skills (undo conditioned arousal, exposure hierarchy, increase activities) • Relapse prevention and discharge Case Formulation Form: Comorbidities Domains 6. Comorbidities: Any co‐occurring conditions that impact sleep? Targets Sleep apnea, if yes, is it adequately treated? Restless Leg Syndrome, if yes, is it adequately treated? Periodic Limb Movement, if yes, is it adequately treated? Chronic pain, if yes, is it adequately √ treated? √ PTSD Others? Manber & Carney, 2015 Case Formulation Form: Other factors Domains 7. Any other factors? Consider sleep environment, care taking duties at night, life phase sleep issues; mental status, and readiness for change. Targets Sleep environment optimal? Care taking or on‐call duties at night? Cognitive or learning issues? What stage of readiness for change? √ Any resistance to engaging in short‐ term behavior changes? 89 When CBT‐I goals conflict with client goals: MI? Goal (often not stated) Problem CBT‐I conflict Avoid fatigue CBT‐I ↑ fa gue, more typically sleepiness Challenge sleep‐fatigue link, tolerate fatigue ST Produce 8 hours (or more) of sleep Typically limits TIB to under 8 CBT‐I values quality not hours quantity Get more done during the day Over‐valuing productivity over rest periods can lead to anxiety and fatigue and insomnia CBT‐I challenges perfectionism and schedules a wind‐down (and relaxation) Experience unconsciousness during sleep Perfectionism about sleep (disregards that wake is part of sleep) Accept that sleep has varying depths and part of sleep is wake Enjoy sleep again Wants to sleep well but also loves/loved sleeping in on weekends Limits TIB and typically results in earlier rise time Recognizing Stages of Change (Prochaska & Norcross, 2002) Enhancing motivation • Support and increase awareness of the motivation to use tools in contemplation: – “It sounds like you are concerned that you have tried stimulus control before and were not able to stick with it 100%. You keep persisting however, so obviously it is pretty important to you.” • Support concrete goals in preparation – “I think I could shave off an hour from my time in bed.” – “That sounds like a good start. We can assess if you are happy with the results, and go from there?” • Empathy allows safe exploration of ambivalence: – “You seem to have a lot on your plate right now and you feel like following a schedule is adding stress. But you also feel really tired.” 90 Problem Plan Tool Fatigue Eliminate jetlag Reduce time-in-bed Increase activation out of bed Address cognitive factors Increase relaxation skills Increase blue light exposure Fatigue management Stimulus control Sleep restriction Behavioral activation Cognitive Therapy Relaxation therapy Schedule light H.E.L.M. Repetitive thoughts Eliminate in bed Test alternative coping Schedule processing Stimulus control Behavioral Activation (TRAC) Pennebaker, Scheduled Worry Using bed as escape Teach model of conditioned arousal, insomnia, avoidance Test whether it is helpful Avoid avoidance Psychoeducation and Cognitive Therapy Lingering in Set clock earlier (advance the sleep phase to get up earlier) bed in Outside-in plan morning/ going to bed too late Behavioral experiment Test other coping skills Stimulus control & Sleep restriction, morning light Behavioral Activation CBT‐I in isolation • CBT‐I validated as a package but also evidence for isolated SC and isolated SRT • The monotherapies allow us to use case formulation for integration into other protocols (e.g., CBT for worry) • CBT‐I as a package is typically delivered as a 4 session biweekly treatment (e.g., Edinger & Carney, 2014) QUESTIONS 91 Selected Readings and Resources Selected Author Books Carney, C. E., & Edinger, J. D. (2010). Insomnia and anxiety. New York, NY: Springer. Carney, C. E., & Manber, R. (2009). Quiet your mind and get to sleep: Solutions to insomnia for those with depression, anxiety, or chronic pain. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Carney, C. E., & Posner, D. (2015). Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia in those with depression: A guide for clinicians. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. Edinger, J. D., & Carney, C. E. (2015). Overcoming insomnia: a cognitive behavioral therapy approach, therapist guide (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Manber, R., & Carney, C. E. (2015). Treatment plans and interventions for insomnia: a case formulation approach. New York, NY: Guilford. Links to Selected Assessment Tools 1. STOPBANG to assess for possible apnea (refer those with scores of 3 or above) http://www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php 2. Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess for excessive sleepiness http://epworthsleepinessscale.com/ 3. Please feel free to use our free app, CBT-I Coach, developed for our training in the US VA system: https://itunes.apple.com/ca/app/cbt-i-coach/id655918660?mt=8 https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.t2.cbti&hl=en Bibliography for Workshop Addis, M. E., & Martell, C. R. (2004). Overcoming depression one step at a time. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Armitage, R. (2000). The effects of antidepressants on sleep in patients with depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 45, 803-809. Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U, . . . Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135, 10-19. Beck, A. T. (1999). Psychoevolutionary view of personality and axis I disorders. In C. R. Cloninger (Ed.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 411-429). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 92 Belleville, G., Guay, C., Guay, B., & Morin, C. M. (2007). Hypnotic taper with or without self-help treatment of insomnia: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 325-335. Bernert, R. A., & Nadorff, M. R. (2015). Sleep disturbances and suicide risk. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 10, 35-39. Blom, K., Jernelov, S., Kraepelien, M., Bergdhal, M. O., Jungmarker, K., Ankartjarn, L., . . . Kaldo, V. (2015). Internet treatment addressing either insomnia or depression, for patients with both diagnoses: a randomized trial. Sleep, 38, 267-277. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (1992). Caffeine use as a model of acute and chronic insomnia. Sleep, 15, 526-536. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (1995). 24-hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep, 18, 581-588. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (1996). Insomnia-nocturnal sleep disruption-daytime fatigue: the consequences of a week of insomnia. Sleep, 19, 453-461. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (1998). The consequences of a week of insomnia II: patients with insomnia. Sleep, 21, 359-368. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (2010). Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14, 9-15. Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (2014). Physiological and medical findings in insomnia: implications for diagnosis and care. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18, 111-122. Bootzin R. R. (1972). A stimulus control treatment for insomnia. Proceedings of the American Psychological Association, 7, 395-396. Borbély, A. A. (1982). A two process model of sleep regulation. Human neurobiology, 1, 195-204. Borbely, A. A., Daan, S., Wirz-Justice, A., & Deboer, T. (2016). The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. Journal of Sleep Research, 25, 131-143. Broomfield, N. M., & Espie, C. A. (2003). Initial insomnia and paradoxical intention: an experimental investigation of putative mechanisms using subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 31, 313-324. Buscemi, N., Vandermeer, B., Hooton, N., Pandya, R., Tjosvold, L., Hartling, L., . . . Vohra, S. (2005). The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disoders. A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 1151-1158. Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2006). Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep, 29, 1155-1173. 93 Buysse, D. J., Germaine, A., Moul, D. E., Franzen, P. L., Brar, L. K., Fletcher, M. E., . . . Monk, T. H. (2011). Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171, 887-895. Casement, M. D., & Swanson, L. M. (2012). A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clinical Psychology Reviews, 32, 566-574. Carney, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Krystal, A. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2012). The Consensus Sleep Diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep, 35, 287-302. Carney, C. E., & Edinger, J. D. (2006). Identifying critical dysfunctional beliefs about sleep in primary insomnia. Sleep, 29, 440-453. Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Kuchibhatla, M., Lachowski, A. M., Bogouslavsky, O., Krystal, A. D., & Shapiro, C. M. (2017). Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep, 40. Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Manber, R., Garson, C., & Segal, Z. V. (2007). Beliefs about sleep in disorders characterized by sleep and mood disturbance. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 179-188. Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Meyer, B., Lindman, L., & Istre, T. (2006). Daily activities and sleep quality in college students. Chronobiology International, 23, 623-637. Carney, C. E., Harris, A. L., Falco, A., & Edinger, J. D. (2013). The relation between insomnia symptoms, mood, and rumination about insomnia symptoms. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 9, 567-575. Carney, C. E., & Waters, W. F. (2006). Effects of a structured problem-solving procedure on pre-sleep cognitive arousal in college students with insomnia. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 4, 13-28. Chambers, M. J. (1994). Actigraphy and insomnia: a closer look. Part 1. Sleep, 17, 405-408. Chaudhuri A., & Behan, P. O. (2004). Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet, 363, 978-988. Chung, F., Yegneswaran, B., Liao, P., Chung, S. A., Vairavanathan, S., Islam, S., Khajehdehi, A., & Shapiro, C. M. (2008). STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology, 108, 812-821. Colvonen, P. J., Masino, T., Drummond, S. P., Myers, U. S., Angkaw, A. C., & Norman, S. B. (2015). Obstructive sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11, 513-518. Craske, M. G., Lang, A. J., Aikins, D., & Mystkowski, J. L. (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy for nocturnal panic. Behavior Therapy, 36, 43-54. 94 Currie, S. R., Wilson, K. G., Pontefract, A. J., deLaplante, L. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 407-416. Davies, R., Lacks, P., Storandt, M., & Bertelson, A. D. (1986). Countercontrol treatment of sleepmaintenance insomnia in relation to age. Psychology and Aging, 1, 233-238. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (2016). Research review on mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. Falls Church, VA: Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. Edinger, J. D., Means, M. K., Carney, C. E., & Manber, R. (2011). Psychological and behavioral treatments for insomnia II: implementation and specific populations. In M. H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W. C. Dement (Eds.), Principles and practice of sleep medicine (5th ed.) (pp. 884-904). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. Edinger, J. D., Olsen, M. K., Stechuchak, K. M., Means, M. K., Lineberger, M. D., Kirby, A., & Carney, C. E. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominantly with mixed psychiatric disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep, 32, 499-510. Edinger, J. D., Wohlgemuth, W. K., Krystal, A. D., & Rice, J. R. (2005). Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 2527-2535. Edinger, J. D., Wohlgemuth, W. K., Radtke, R. A., Coffman, C. J., & Carney, C. E. (2007). Dose-response effects of cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep, 30, 203-212. Epstein, D. R., Babcock-Parziale, J. L., Herb, C. A., Goren, K., & Bushnell, M. L. (2013). Feasibility test of preference-based insomnia treatment for Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Rehabilitation Nursing, 38, 120-132. Espie, C. A., Broomfield, N. M., MacMahon, K. M., Macphee, L. M., & Taylor, L. M. (2006). The attentionintention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10, 215-245. Espie, C. A., Fleming, L., Cassidy, J., Samuel, L., Taylor, L. M., White, C. A., . . . Paul, J. (2008). Randomized controlled clinical effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy compared with treatment as usual for persistent insomnia in patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 46514658. Evenson, K. R., Goto, M. M., & Furberg, R. D. (2015). Systematic review of the validity and reliability of consumer-wearable activity trackers. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 159. Fava, M., McCall, W. V., Krystal, A., Wessel, T., Rubens, R., Caron, J., . . . Roth, T. (2006). Eszopiclone coadministered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 1052-1060. 95 Ford, D. E., & Kamerow, D. B. (1989). Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? Journal of the American Medical Association, 262, 1479-1484. Fredholm, B. B., Yang, J., & Wang, Y. (2017). Low, but not high, dose caffeine is a readily available probe for adenosine action. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 55, 20-25. Gehrman, P. R., Hall, M., Barilla, H., Buysse, D., Perlis, M., Gooneratne, N., & Ross, R. J. (2016). Stress reactivity in insomnia. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 14, 23-33. Germain, A., Shear, M. K., Hall, M., & Buysse, D. J. (2007). Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for PTSD-related sleep disturbances: a pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 627-632. Germain, A., Richardson, R., Stocker, R., Mammen, O., Hall, M., Bramoweth, A. D., ... & Buysse, D. J. (2014). Treatment for insomnia in combat-exposed OEF/OIF/OND military veterans: Preliminary randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 61, 78-88. Haponik, E. F., Frye, A. W., Richards, B., Wymer, A., Hinds, A., Pearce, K., . . . Konen, J. (1996). Sleep history is neglected diagnostic information. Challenges for primary care physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 11, 759-761. Harvey, A. G., & Farrell, C. (2003). The efficacy of a Pennebaker-like writing intervention for poor sleepers. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 1, 115-124. Harvey, A. G., & Payne, S. (2002). The management of unwanted pre-sleep thoughts in insomnia: distraction with imagery versus general distraction. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 267277. Harvey, A. G., & Talbot, L. S. (2010). Behavioral experiments. In M. Perlis, M. Aloia, & B. Kuhn (Eds.), Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders (pp. 71-77). New York: Academic Press. Hoelscher, T. J., & Edinger, J. D., (1988). Treatment of sleep-maintenance insomnia in older adults: Sleep period reduction, sleep education, and modified stimulus control. Psychology and Aging, 3, 258263. Howell, D., Oliver, T. K., Keller-Olaman, S., Davidson, J., Garland, S., Samuels, C., . . . Taylor, C. (2012). A Pan-Canadian practice guideline: prevention, screening, assessment and treatment of sleep disturbances in adults with cancer. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Advisory Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology. Jacobs, G. D., Pace-Schott, E. F., Stickgold, R., & Otto, M. W. (2004). Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 1888-1896. Johns, M. W. (1991). A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep, 14, 540-545. 96 Jungquist, C. R., O’Brien, C., Matteson-Rusby, S., Smith, M. T., Pigeon, W. R., Xia, Y., . . . Perlis, M. L. (2010). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Medicine, 11, 302-309. Kales, A., Soldatos, C. R., Bixler, E. O., & Kales, J. D. (1983). Early morning insomnia with rapidly eliminated benzodiazepines. Science, 220, 95-97. Karp, J. F., Buysse, D. J., Houk, P. R., Cherry, C., Kupfer, D. J., & Frank, E. (2004). Relationship of variability in residual symptoms with recurrence of major depressive disorder during maintenance treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1877-1884. Kay, D. B., Karim, H. T., Soehner, A. M., Hasler, B. P., Wilckens, K. A., James, J. A., . . . Buysse, D. J. (2016). Sleep-wake differences in relative regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose among patients with insomnia compared with good sleepers. Sleep, 39, 1779-1794. Kohn, L., & Espie, C. A. (2005). Sensitivity and specificity of measures of the insomnia experience: A comparative study of psychophysiologic insomnia, insomnia associated with mental disorder and good sleepers. Sleep, 29, 104-112. Kuo, T., Manber, R., & Loewy, D. (2001). Insomniacs with comorbid conditions achieved comparable improvement in a cognitive behavioral group treatment program as insomniacs without comorbid depression. Sleep, 14, A62. Krakow, B., Hollifield, M., Johnson, L., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Warner, T. D., . . . Prince, H. (2001). Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 537545. Krupinski, J., & Tiller, J. W. (2001). The identification and treatment of depression by general practitioners. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 827-832. Kyle, S. D., Morgan, K., Spiegelhalder, K., & Espie, C. A. (2011). No pain, no gain: an exploratory withinsubjects mixed-methods evaluation of the patient experience of sleep restriction therapy (SRT) for insomnia. Sleep Medicine, 12, 735-747. Levey, A. B., Aldaz, J. A., Watts, F. N., & Coyle, K. (1991). Articulatory suppression and the treatment of insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 85-89. Lew, H. L., Pogoda, T. K., Hsu, P. T., Cohen, S., Amick, M. M., Baker, E., . . . Vanderploeg, R. D. (2010). Impact of the “polytrauma clinical triad” on sleep disturbance in a department of veterans affairs outpatient rehabilitation setting. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 89, 437-445. 97 Lichstein, K. L., Riedel, B. W., Wilson, N. M., Lester, K. W., & Aguillard, R. N. (2001). Relaxation and sleep compression for late-life insomnia: a placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 227-239. Lichstein, K. L., Wilson, N. M., & Johnson, C. T. (2000). Psychological treatment of secondary insomnia. Psychology and Aging, 15, 232-240. Lineberger, M. D., Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., & Means, M. K. (2006). Defining insomnia: Quantitative criteria for insomnia severity and frequency. Sleep, 29, 479-485. Littner, M., Hirshkowitz, M., Kramer, M., Kapen, S., Anderson, W. M., Bailey, D., Berry, R. B., . . . Woodson, B. T. (2003). Practice parameters for using polysomnography to evaluate insomnia: an update. Sleep, 26, 754-760. Mahmood, O., Rapport, L. J., Hanks, R. A., & Fichtenberg, N. L. (2004). Neuropsychological performance and sleep disturbance following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 19, 378-390. Manber, R., Edinger, J. D., Gress, J. L., San Pedro-Salcedo, M. G., Kuo, T. F., & Kalista, T. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep, 31, 489-495. Mantua, J., Gravel, N., & Spencer, R. M. (2016). Reliability of sleep measures from four personal health monitoring devices compared to research-based actigraphy and polysomnography. Sensors, 16, 646. Martell, C. R., Dimidjian, S., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: a clinician’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford. Mathias, J. L., & Alvaro, P. K. Prevalence of sleep disturbances, disorders, and problems following traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine, 13, 898-905. Means, M. K., & Edinger, J. D. (2007). Graded exposure therapy for addressing claustrophobic reactions to continuous positive airway pressure: a case series report. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 5, 105116. Mellman, T. A., & Uhde, T. W. (1989). Sleep panic attacks: New clinical findings and theoretical implications. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 1204-1207. Minkel, J., Moreta, M., Muto, J., Htaik, O., Jones, C., Basner, M., & Dinges, D. (2014). Sleep deprivation potentiates HPA axis stress reactivity in healthy adults. Health Psychology, 33, 1430-1434. Morawetz, D. (2003). Insomnia and depression: Which comes first? Sleep Research Online, 5, 77-81. 98 Morgenthaler, T. I., Lee-Chiong, T., Alessi, C., Friedman, L., Aurora, R. N., Boehlecke, B., . . . Zak, R. (2007). Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep, 30, 1445-1459. Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Morin, C. M., Bootzin, R. R., Buysse, D. J., Edinger, J. D., Espie, C. A., & Lichstein, K. L. (2006). Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (19982004). Sleep, 29, 1398-1414. Morin, C. M., Culbert, J. P., & Schwartz, S. M. (1994). Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: A meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1172-1180. Morin, C. M., Hauri, P. J., Espie, C. A., Spielman, A. J., Buysse, D. J., & Bootzin, R. R. (1999). Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep, 22, 1134-1156. Morin, C. M., Stone, J., McDonald, K., & Jones, S. (1994). Psychological management of insomnia: A clinical replication series with 100 patients. Behavior Therapy, 25, 291–309. Morin, C. M., Vallieres, A., Guay, B., Ivers, H., Savard, J., Merette, C., . . . Baillargeon, L. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 2005-2015. National Institutes of Health (2005). NIH State of the Science Conference statement on manifestations of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 1, 412-421. Nierenberg, A. A., Keefe, B. R., Leslie, V. C., Alpert, J. E., Pava, J. A., Worthington, J. J., . . . Fava, M. (1999). Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60, 221-225. Ong, J. C., Manber, R., Segal, Z, Xia, Y., Shapiro, S., & Wyatt, J. K. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep, 37, 1553-1563. Ong, J. C., Shapiro, S. L., & Manber, R. (2008). Combining mindfulness meditation with cognitivebehavior therapy for insomnia: a treatment-development study. Behavior Therapy, 39, 171-182. Ong, J. C., Shapiro, S. L., & Manber, R. (2009). Mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a naturalistic 12-month follow-up. Explore, 5, 30-36. Orff, H. J. (2009). Traumatic brain injury and sleep disturbance: a review of current research. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 24, 155-165 Ouellet, M. C., Beaulieu-Bonneau, S., & Morin, C. M. (2015). Sleep-wake disturbances after traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurology, 14, 746-757. 99 Ouellet, M. C., & Morin, C. M. (2004). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia associated with traumatic brain injury: a single-case study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 1298-1302. Qaseem, A., Kansagara, D., Forciea, M. A., Cooke, M., & Denberg, T. D. (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165, 125-133. Padesky, C. A. (1993). Socratic questioning: changing minds or guiding discovery? Keynote address delivered at the meeting of the European Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, London, UK. Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2001). Stages of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 443-448. Raskind, M. A., Peskind, E. R., Hoff, D. J., Hart, K. L., Holmes, H. A., Warren, D., . . . McFall, M. (2007). A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 928-934. Raskind, M. A., Peskind, E. R., Kanter, E. D., Petrie, E. C., Radant, A., Thompson, C. E., . . . McFall, M. (2003). Reduction of nightmares and other PTSD symptoms in combat veterans by prazosin: a placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 371-373. Ree, M., & Harvey, A. G. (2004). Insomnia. In J. Bennet-Levy, G. Butler, M. Fennell, et al., (Eds.), Oxford guide to behavioral experiments in cognitive therapy (287-305), Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Riedel, B. W., Lichstein, K. L., & Dwyer, W. O. (1995). Sleep compression and sleep education for older insomniacs: Self-help versus therapist guidance. Psychology and Aging, 10, 54-63. Riedner, B. A., Goldstein, M. R., Plante, D. T., Rumble, M. E., Ferrarelli, F., Tononi, G., & Benca, R. M. (2016). Regional patterns of elevated alpha and high frequency electroencephalographic activity during nonrapid eye movement sleep in chronic insomnia: a pilot study. Sleep, 39, 801-812. Rybarczyk, B., Lopez, M., Benson, R., Alsten, C., & Stepanski, E. (2002). Efficacy of two behavioral treatment programs for comorbid geriatric insomnia. Psychology and Aging, 17, 288-298. Sateia, M. J., Buysse, D. J., Krystal, A. D., Neubauer, D. N., and Heald, J. L. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13, 307-349. Savard, J., Simard, S., Ivers, H., & Morin, C. M. (2005). Randomized study on the efficacy of cognitivebehavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part II: Immunologic effects. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 6097-6106. 100 Schutte-Rodin, S., Broch, L., Buysse, D., Dorsey, C., & Sateia, M. (2008). Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4, 487-504. Siriwardena, A. N., Apekey, T., Tilling, M., Dyas, J. V., Middleton, H., & Orner, R. (2010). General practitioners’ preferences for managing insomnia and opportunities for reducing hypnotic prescribing. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16, 731-737. Smith, M. T., Huang, M. I., & Manber, R. (2005). Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic insomnia occurring within the context of medical and psychiatric disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 559-592. Smith, M. T., Perlis, M. L., Park, A., Smith, M. S., Pennington, J., Giles, D. E., & Buysse, D. J. (2002). Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 5-11. Spielman, A. J., Caruso, L. S., & Glovinsky, P. B. (1987). A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 10, 541-553. Spielman, A. J., Saskin, P., & Thorpy, M. J. (1987). Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep, 10, 45-56. Swift, N., Stewart, R., Andiappan, M., Smith, A., Espie, C. A., & Brown, J. S. (2012). The effectiveness of community day-long CBT-I workshops for participants with insomnia symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of sleep research, 21, 270-280. Taylor, H. R., Freeman, M. K., & Cates, M. E. (2008). Prazosin for treatment of nightmares related to posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 65, 716-722. Troxel, W. M., Kupfer, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Frank, E., Thase, M. E., Miewald, J. M., & Buysse, D. J. (2012). Insomnia and objectively measured sleep disturbances predict treatment outcome in depressed patients treated with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73, 478-485. Verbeek, I., Schreuder, K., & Declerck, G. (1999). Evaluation of short-term nonpharmacologic treatment in a clinical setting. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47, 369-383. Vitiello, M. V., Rybarczyk, B., Von Korff, M., & Stepanski, E. J. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 5, 355-362. Vincent, N., & Lionberg, C. (2001). Treatment preferences and patient satisfaction in chronic insomnia. Sleep, 24, 411-417. Warden, D. (2006). Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 21, 398-402. 101 Watanabe, N., Furukawa, T. A., Shimodera, S., Morokuma, I., Katsuki, F., Fujita, H., . . . Perlis, M. L. (2011). Brief behavioral therapy for refractory insomnia in residual depression: an assessorblind, randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72, 1651-1658. Waters, W. F., Hurry, M. J., Binks, P. G., Carney, C. E., Fuller, K. H., Betz, B., . . . Tucci, J. M. (2003). Behavioral and hypnotic treatments for insomnia subtypes. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 1, 81101. Webb, W. B. (1988). An objective behavioral model of sleep. Sleep, 11, 488-496. Wilson, S. J., Nutt, D. J., Alford, C., Argyropoulos, S. V., Baldwin, D. S., Bateson, A. N., . . . Wade, A. G. (2010). British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24, 1577-1600. Woznica, A. A., Carney, C. E., Kuo, J. R., & Moss, T. G. (2015). The insomnia and suicide link: Toward an enhanced understanding of this relationship. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 22, 37-46. Wright, K. M., Britt, T. W., Bliese, P. D., Adler, A. B., Picchioni, D., & Moore, D. (2011). Insomnia as predictor versus outcome of PTSD and depression among Iraq combat veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 1240-1258. Wyatt, J. K., Dijk, D. J., Ritz-de Cecco, A., Ronda, J. M., & Czeisler, C. A. (2006). Sleep-facilitating effect of exogenous melatonin in healthy young men and women is circadian-phase dependent. Sleep, 29, 609-618. Zayfert, C., & DeViva, J. C. (2004). Residual insomnia following cognitive behavior therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 69-73. 102 NOTES NOTES