Understanding and Using English Grammar. Teacher's Guide 2017 5th -285p

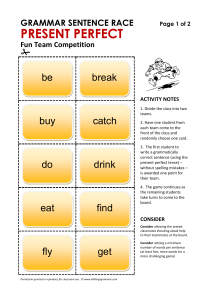

advertisement