Indigenous Australian land management

before the European settlement in 1788:

a review article

Margaret L. Faull

Bill Gammage. The Biggest Estate on Earth: how

Aborigines made Australia (Allen & Unwin, Sydney,

Australia, 2011). 180 × 250 mm. 434 pp. 59

illustrations. ISBN 978 1 74237 748 3. Price

AUD $49.99.

Australia has an incredible diversity of unique

forms of life; in addition to the well-known

marsupials, it has some 25,000 native plant

species, 10 per cent of the world’s total, including

1,000 out of the 1,300–1,400 acacia species in

the world (pp. 111–14; unattributed references

simply with page numbers are all to Gammage

2011). Of 770 known eucalypt species, only five

are not native to Australia (pp. 115–17). But in

recent years the Australian landscape has been

beset by ever-increasing problems. In addition

to the usual fluctuations of climate that made

Dorothea McKellar refer in her national poem

to a land of ‘droughts and flooding rains’, bush

fires have raged more frequently and with a

greater intensity, salination of the land is an everyincreasing problem (pp. 110–11) and droughts

and floods are occurring more and more often,

partly as a result of climate change (as with bush

fires) and partly as a result of farming practices

(as with salination). This has led people to look at

alternative ways of doing things and how others

have farmed in the past or elsewhere in the world.

One outstanding work in this regard, Back from the

Brink, by Peter Andrews (2006), advocates a new

way of managing the Australian landscape. Now,

to complement that work, comes this magisterial

DOI: 10.1080/01433768.2014.981396

study, looking at how Australia’s indigenous

inhabitants1 managed this vast and diverse country

so successfully for tens of thousands of years.

This book is essential reading, not just for those

studying the Australian landscape, but as well

for those interested in environmental matters in

general, while it also has implications for studies

of Mesolithic societies of the past.

It is but seldom that a work appears which

funda­mentally changes how the general public,

as opposed to the specialists in the field, view

the exploitation of the landscape, but this is such

a book. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution

was built on the work of previous scholars,

such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, but needed his

meticulous examination of all the evidence in

The Origin of Species in order to convince the rest

of the world. Similarly the ideas in this book

have been much discussed by specialists in the

field, but it is Bill Gammage who draws together

evidence from a multitude of sources in a book

for the general public to show that the Australian

indigenous people also systematically managed

their entire landscape in as sophisticated a manner

as that developed in Europe with the Agricultural

Revolution.

The main sources he uses are in fact the

early European commentators, who frequently

recorded the deliberate setting of fires by the local

inhabitants, but completely failed to appreciate

the significance of what they observed. They

were incapable of comprehending that the people

described by Charles Darwin, amongst others,

68

landscape history

as ‘a set of harmless savages’ (pp. 43, 309, 312)

had the ability to manipulate their environment

in just as sophisticated a way as any gentleman

farmer on the estates of the Old World from

which they had themselves come. The general

view was that the indigenous people moulded

their way of life to the country, rather than

the country being moulded by those people

(p. xxii). Yet the eminent Australian historian,

Henry Reynolds, points out in the introduction

that Bill Gammage ‘establishes without question

the scale of Aboriginal land management, the

intelligence, skill and inherited knowledge which

informed it’ (p. xxiii). A very few perspicacious

observers did realise this, such as Edward Curr

in the mid-nineteenth century (p. 2), and indeed

the great Yorkshire explorer, Captain James

Cook, acknowledged that ‘they are far more

happier than we Europeans’ and that ‘they think

themselves provided with all the necessarys of

Life’ (p. 309). Modern research has shown how

far the indigenous inhabitants of Australia were

from being that ‘set of harmless savages’ and how

they interpreted the meaning of the landscape

(Benterrak, Muecke & Roe 1996).

The early explorers and observers, including

Captain Cook (p. 5), described the landscape that

they found as being like a country gentleman’s

park with grassy slopes. For example, Watkin

Tench, who took part in the First Settlement of

1788 and said that ‘he has spoken from actual

observation’ (1789, p. 15), wrote that:

The face of the country is such as to promise

success whenever it shall be cultivated, the trees

being at a considerable distance from each other and

the intermediate space filled, not with underwood,

but a thick rich grass growing in the in utmost

luxuriancy (ibid., p. 65).

Indigenous people saw themselves as having

a religious duty to look after all of the land

(p. 133), which Gammage (p. 1) argues was one

great Australian estate that they considered to be

single and universal. They believed that they had

an obligation to leave the world as they found it

(p. 2), so that theology and ecology were fused

(p. 133): people did not ‘own’ land; the land

owned them (pp. 142–3). This was the same with

all tribes across the whole of Australia (p. 14),

including Tasmania, which was cut off from

the mainland about 9,000 b.c (p. 20). On the

whole, their obedience to the Law discouraged

fundamental changes (p. 124), although there was

one major change in about 2,000 b.c. (see below).

The prime tool that they used for this was fire,

unlike the plough and domesticated animals of

the Old World. Apart from the dingo, Australia

has no native animals that can be domesticated

and farming is made more difficult by the

extreme climatic variations resulting from the El

Nino Southern Oscillation, which causes more

differences between years than between seasons.

By using fire people could manage the plants

more easily than by laboriously cultivating them

(p. 297); in northern Australia they were in contact

with people who were sedentary farmers (Isaacs

1980, pp. 261–77), but realised that their own

methods were more effective (pp. 297–8, 300).

In fact, European women worked harder than

indigenous women, who nevertheless produced

more food and were probably happier (pp. 302,

310–11). But the times, intensity and frequency

of burning were much more complex than the

modern, crude method of ‘burning off ’, which

is usually done in the winter season, whereas

the indigenous people burned throughout the

year, mainly during the summer, when it is now

illegal (p. 169), and controlled the fires by the

time of day that they were lit (p. 56). There were

sanctions against improper burning, and setting

fires was the responsibility of the senior men

(pp. 160–1), who knew the intervals required

between burning.2

Again and again landscapes were recorded

in the early years of the Settlement that did

not accord with what would have been found

naturally. Eucalypts were found growing in rain

forests, which is not normal (pp. 12–13), but in

other places where they would be expected there

were no gum trees, which can only be killed

by repeated and deliberately set fires (pp. 12–

14). Perennial grassland, as seen by the early

observers, can only be produced in the Australian

environment by repeated burning every two to

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

four years (p. 14) and spinifex country will not

support food plants until it has been burned

(p. 14). The degree of control of the environment

is shown by early pictures depicting eucalyptus

forest with no undergrowth almost immediately

next to dense rain forest (p. 83), while elsewhere

trees occurred in some areas but not in others,

although the soils were identical (p. 6) and where

trees, when planted, grew well (p. 9). It was noted

that typically grass grew on good soil, with trees

on the poor land, which is the reverse of what

would be expected in nature (p. 6).

The indigenous inhabitants manipulated the

environment by use of what Bill Gammage calls

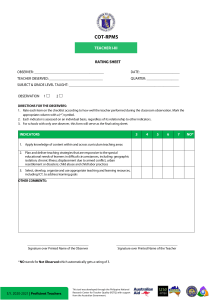

‘templates’. Plates I, II and III3 of illustrations and

accompanying text from the Biggest Estate on Earth

illustrate the principles and operation of three

such templates. The various types are discussed

in detail in the book; for example one aim was

to associate water, grass and forest, in order to

entice forest-dwelling game out to feed and drink.

This facilitated hunting by the men (pp. 61, 90–2,

199–210), while the women gathered vegetables

and fruit in areas screened so that they would

not startle the animals (p. 79). People made sure

to hunt different mobs of prey in rotation, with

sanctuaries to safeguard game (pp. 284‒5), so that

individual groups of animals would not become

spear-shy (p. 216). Another template ensured that

animals were kept away from plants that people

used as food (p. 214). Modified water systems

were created to trap fish and eels (p. 283) and, as

well, possums, emus and cassowaries were reared

and then fattened for eating; fish and crayfish

were moved to other parts of the country and

dingoes were domesticated (p. 282).

Indigenous people were in fact manipulating

plants as well as animals, with bans on eating both

plants and animals at breeding time (pp. 283‒4),

but allowing the culling of animals when they

were deemed to be in excess (pp. 285‒7). Women

often moved plants to more favourable areas (p.

294), and seed was traded between people as gifts

at the major traditional gatherings (pp. 295, 297).

On his 1844 expedition in north-west New South

Wales, Charles Sturt saw native granaries (p. 295).

The women were always careful to leave some yam

69

roots behind to ensure that they regenerated and

millet seed was scattered and then people waited

for rain, as millet crops a year after rain (p. 304).

Australian indigenous people regularly made

use of virtually every available plant in some way

(p. 111), eating a greater variety of foods than

any other society on earth (p. 151; see also Jones

& Meehan 1989; Meehan & Jones 1986). Elders

were able to name 420 species with details of

each (pp. 288–9), whereas Europeans tend to rely

on about thirty basic foodstuffs, especially wheat

and dairy products. Indeed the areas that the

incomers thought were the most barren were the

ones most productive of a wide variety of plants

for those who knew how to use them (pp. 169,

239). Once indigenous people living on reserves

were forced to adopt a diet high in white flour

and sugar, rates of Type II diabetes soared to

amongst the highest levels in the world. When,

however, they returned to their traditional way of

life, in the course of teaching indigenous school

children about indigenous lifestyles and customs,

their diabetes disappeared. This was one of the

first times that it had been shown that dietary

changes could have a substantial effect on Type

II diabetes, which had previously been thought

to be irreversible, and has made Australia into

one of the centres of the world in research into

diabetes (see, for example, Gallop 2003).

The incoming settlers were conceptually

incapable of appreciating the levels of sophistica­

tion of indigenous landscape manage­ment. From

the earliest years of the settlement, views were

expressed such as those of Watkin Tench:

The country, I am of opinion, would abound with

birds did not the natives, by perpetually setting fire

to the grass and bushes, destroy the greater part of

the nests (1789, p. 241).

The incomers believed that fire was used only

for hunting:

When the Indians in their hunting parties set fire to

the surrounding country (which is a very common

custom), the squirrels, opossums and other animals

who live in trees, flee for refuge into these holes,

whence they are easily dislodged and taken (ibid.,

p. 112).

70

Plate I. Illustration and text from Gammage 2011, p. 67 (© text and illustration Bill Gammage).

landscape history

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

71

Plate II. Illustration and text from Gammage 2011, p. 91 (© text Bill Gammage; illustration from Lycett 1830 — out of

copyright — held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra); Joseph Lycett (1774–1828) was a convict artist.

72

landscape history

There were two consequences of this. Firstly,

the incomers assumed that all the resources were

naturally available and used them freely. The

original inhabitants had always restricted their

own numbers to ensure that they remained well

within the capabilities of the land to support

them, even in a one-hundred-year drought (p.

150). The incomers were oblivious to this, while

despising the landscape (‘a country destitute of

natural resources’: Tench 1789, p. 92), they very

rapidly indeed began to use up those resources.

Tench commented that

fish, which on our arrival and for a short time after

had been tolerable plenty, were become so scarce as

to be rarely seen at the tables of the first amongst

us’ (ibid., p. 65).

In addition to the smallpox that they had

inadvertently introduced, the local inhabitants of

the Sydney area also very soon began to starve.

Tench reported of the body of a dead woman,

with that of a child nearby, that it ‘showed that

famine, superadded to disease, had occasioned

her death’ (ibid., p. 103). And when the starving

people complained, as for example those at

Parramatta who ‘expressed great dissatisfaction

at the number of white men who had settled in

their former territories’, the response was that

‘the detachment at that post was reinforced on

the following day’ (ibid., p. 140). And when they

tried to obtain potatoes from the gardens of

those depriving them of their nutrition, they

were condemned as robbers and killed (ibid.,

pp. 176–7). This sort of deprivation continued

throughout Australia, as incomers selected for

themselves the areas that were most valued by

the indigenous people (p. 308).

Secondly, the Europeans saw the fires as a

threat, to such an extent that laws were passed, for

example in West Australia in 1847, to imprison or

flog indigenous people who lit fires (pp. 97, 312).

But to the indigenous people the use of fire to

care for the land was a religious imperative, even

in the face of death, so that people, while being

hunted down and killed and knowing that fire

would betray their location, still felt obliged to

burn the land (pp. 137–8), becoming effectively

religious martyrs. Once the indigenous people

were no longer allowed to control the landscape,

it began to revert to the state in which it would

have been had it not been burned, with a great

deal of damage being done even in the first ten

years after the First Settlement (pp. 313, 316–20).

Uncultivated and ungrazed Australian landscapes

are now totally different, with many more trees,

from those of 1788 (pp. 11, 195–9, 210). The

islands of the Whitsunday Passage, described by

Captain Cook as so covered with grass that one

was named Grassy Island, are now wooded (p. 5).

White incomers did not believe that they could

learn anything from the indigenous people. In

fact it was the common expectation that they

would eventually all die out (p. xxi; Thomas 2003,

pp. 67, 178) that led to their incarceration on

reserves; the disastrous results of this policy still

blight Australian society. The parks that were so

attractive to Europeans have now gone as a result

of overgrazing, and the introduced European

grasses are winter- or spring-flowering annuals

(pp. 108-9), unlike the native grasses which are

perennial and reshoot green when burned and

which flower in the summer, when they were

needed as feed for the native animals (pp. 17,

32–6, 56).

While breaking new ground, it is depressing

to see how long it has taken for these ideas to be

put forward in print for the general public and

granted a degree of acceptance, when Australian

botanists and landscape historians have been well

aware of many of the problems raised here and

the damage that has consequently been done

to the fragile Australian landscape. My mother

graduated in botany from Sydney University in

1939 and she often bemoaned many of these

effects on the landscape. In particular she was

well aware of the damage done to the soil and

to the native flora by the sharp cloven hooves of

sheep and cattle and the shod hooves of horses.

She maintained that Australian native grasses had

evolved alongside the native fauna; the long legs

of wallabies and kangaroos in contact with the

ground spread their weight and so do not damage

native grasses in the same way as the hooves

of the ungulates did. And that then, when the

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

delicate native grasses were replaced by farmers

with foreign species, these led to the problems

of erosion outlined by Gammage (pp. 32–4,

106‒8, 111). Indeed it has recently been argued

that similar environmental damage has been done

in Britain by sheep, which are not indigenous to

the United Kingdom, but come originally from

Mesopotamia (Monbiot 2013).

She was similarly horrified by the indiscrimin­

ate ‘burning off ’, so beloved of many Australian

farmers (p. 216) and so unlike the carefully

selective and frequent burning done by the

indigenous people, who confined fire-sensitive

species to poor areas with little fuel (p. 164).

Her view was that such regular burning, without

reference to the nature of the plants being burned,

killed those plants that were fire-sensitive, while

encouraging the overgrowth of fire-dependent

plants. These then became the dominant species

and, having developed to promote fire, with

their dominance they then caused the larger and

fiercer fires that now threaten settlements. The

pre-1788 system maintained a balance in the

ecosystem (with fire-sensitive and fire-tolerant/

dependent plants, growing side by side; p. 11),

which then became seriously out of kilter with

regular burning off.

Other Australian landscape historians and

archaeologists have previously addressed these

issues (Blainey 1975; Flannery 1994; Jones 1969;

1980; 1985; 1995), the late Professor Rhys

Jones, for example, dealt with how fire was

traditionally used in ‘cleaning up country’ to

prevent dangerous conflagrations (Jones 1980)

and ‘firestick farming’ to assist with hunting

(Jones 1969). Bill Gammage, who is a landscape

historian (p. xxiii), albeit one with a botanist for

a father (p. 326), has acknowledged their insights

into the indigenous use of fire, although not all

their work reached as wide an audience as this

book has done.

Gammage deals well with the problems

of introduced animal and plant species. In

the nineteenth century there was actually an

Acclimatisa­tion Society dedicated to experiment­

ing to discover which European plant and animal

species were best suited to Australian conditions

73

((Brown-May & Swain 2005, pp. 7–8), rather

than looking at which Australian conditions

could accommodate European species without

endangering the ecosystem. Unfortunately,

despite protests as early as 1868 — in that case

against the depredations of introduced sparrows

(ibid., p. 7), now endemic in Australian cities,

— this attitude survived well into the twentieth

century; all Australians are well aware of the

extraordinary damage done to native fauna by

introduced species against which the indigenous

species have not evolved defences. The worst

culprits are camels, foxes, rabbits, rats, domestic

cats gone feral and, worst of all, poisonous cane

toads. The toads were introduced from Hawaii in

1935 to try to control the native cane beetle and

are now spreading across Queensland and the

Northern Territory, decimating virtually all other

species in their path. One introduced species that

Gammage does not mention is the ubiquitous

water-hungry willow tree. In the 1960s my mother

was appalled to see willows being deliberately

planted throughout the Snowy Mountains of

New South Wales and argued fiercely with the

managers who were sponsoring this destructive

and misguided programme; since then willows

have spread far and wide in the Snowy and

concerted efforts are now having to be made to

eradicate them, a much more difficult task than

introducing them had been.

It has to be admitted that not all Australians,

including a number of those who have reviewed

the book, accept the basic premise of this work,

as Gammage himself acknowledges (pp. 325–42).

Indeed the evidence of early paintings showing

extensive grasslands and scattered trees has in

the past not been accepted as accurate; as a

school child in Sydney in the 1960s, I was taught

that the first artists did not know how to depict

the Australian landscape, so used European

templates, and it was only in the late nineteenth

century that the artists of the Heidelberg School

mastered it. It is certainly true that the early artists

did not understand how to paint the leaves of

the eucalypts, which hang down. They tended to

show them, as they had been taught in Europe, as

massed leaves (see the trees in Pls II and III). It

74

landscape history

Plate III. Illustration and text from Gammage 2011, pp. 92–3 (© text Bill Gammage; illustration from Lycett 1830 — out

of copyright — held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra).

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

has been pointed out that some of the drawings

have impossible perspectives or were by artists

who had not actually seen the views depicted,

so that the drawings may have been produced

to reflect the written descriptions or indeed ‘the

class project of settlement’ (Neale 2013). But

Gammage believes that the artists’ recording

of the overall proportions of grass to trees is

accurate and in accordance with the early written

descriptions (pp. 18–19).

Other objections are that the book is simplistic

in assuming a unity of religious beliefs about the

Dreaming throughout the whole of Australia,

drawn with a broad brush, and that the sources

of evidence used are overwhelmingly those of

the white settlers, rather than drawing directly on

information obtained from indigenous inform­ants,

whether contemporary or recorded earlier (ibid.).

There are certainly indigenous communities living

remote from white settlement, in areas such as the

Northern Territory, who still retain knowledge of

traditional ways. Indeed, as mentioned above, in

recent years the transmission of this knowledge

to indigenous school children has been actively

promoted. So there are certainly indigenous elders

who could have been consulted for their views

on the arguments put forward by Gammage, and

this is certainly a major shortcoming of the book.

One commentator has pointed out that this

book fits into the ‘quest for the Grand National

Narrative’ of Australia (Lunt 2013). In recent

years Australians have been re-examining their

history; some of this has been critical, such

as the question of the stolen generation of

mixed-race children or that of the shipping of

British ‘orphans’ to Australia. But on the other

hand there also has been a movement for an

encompassing national identity and The Biggest

Estate on Earth could be viewed as a highly

polemical part of that debate.

One piece of evidence adduced against

the argument of the book is the fact that the

palynological records show no increase in levels

of burning of the landscape after the arrival of

the Aboriginal people, some 50- to 60,000 years

ago. It is accepted by all sides that the Australian

bush has always burned, as a result of lightning

75

strikes, long before there were any humans on

the continent —70 per cent of Australian plants

either tolerate fire or else require it as an essential

part of their life cycle (p. 1). Eucalypts promote

fire by having bark and leaves containing highly

inflammable oil (p. 27), showing that naturally

occurring fires were a constant feature of the

landscape before human settlement. Gammage

does not argue that the indigenous people intro­

duced increased burning of the landscape, only

that they ensured that the burning was of a

controlled and directed nature, with the intention

of systematically exploiting the agricultural

potential of the Australian landscape.

The questions also arise of, firstly, how this

very intricate knowledge was obtained when, after

more than two centuries of white settlement, we

are only just beginning to grope our way towards

some wider understanding of how to manage

the bush, and, secondly, how such detailed

information was transmitted in a pre-literate

society. An extremely good parallel for western

audiences would be that of development of

knowledge of solar matters in the pre-Roman

period. Recent discoveries, in particular the Nebra

Sky-Disc (dating to the sixteenth to fifteenth

centuries b.c.: Mathias 2012, pp. 28–9; Meller

2002; 2004; for a summarised English version

see Maraszek 2009, p. 32), show an incredibly

sophisticated and advanced knowledge of the

heavens in the European Bronze Age: on the

Nebra Disc a gold circle, crescent and cluster of

dots show the night sky with thirty-two stars, full

moon and crescent moon; the dots represent the

Pleiades, whose disappearance in the Bronze Age

around 10 March at the time of the young new

moon and reappearance around 17 October with

the full moon marked the beginning and end of

the arable farming year in Europe. The Sky-Disc

further encodes two different ways of calculating

when leap years will occur and enables the rising

and setting points of the sun to be tracked

throughout the year (Marazek 2009, pp. 46–50).

In fact it was about 38,000 years ago that the

balance of the Australian flora changed, with a

decrease in rain-forest vegetation and an increase

in eucalypt and acacia woodland. This is usually

76

attributed to the effects of burning begun by the

indigenous inhabitants about that time (Molnar

2004, p. 53); this would be approximately 7,000

years before that great outburst of creativity

in Europe that resulted in such works as the

paintings in the caves of Altamira in Spain and

Chauvet in France (Clottes 2001; Gautheron

2011), while indigenous Australian rock art

appears to pre-date the European examples

by about 10,000 years (Brillaud 2011, p. 38).

So the realisation of how to use fire to mould

the landscape to their requirements came some

12- to 22,000 years after the arrival of the first

humans on the Australian continent. Then, about

2,000 b.c., there was a movement described as

‘intensification’, which is defined as change in

economic systems not initiated by environmental

or other external changes but by social changes

(Lourandos 1997; Lourandos & Ross 1994). At

this time there was an increase in population

and of trade between tribes, development of

more elaborate smaller stone implements, more

exploitation of the landscape, and possibly

development of more elaborate social systems.

A fair idea of how learning could be passed on

in a pre-literate society comes from the classical

references to the druids. Classical writers, such as

Caesar, tell us that it took up to twenty years of

hard work to qualify as a druid (West 2007, pp. 27,

30), while in India the education of a Brahman

took thirty-six years (ibid., p. 30). As they did not

use written records, knowledge of sacred matters,

traditions and poetic wisdom was confined to

the druids, who had to commit everything to

memory and who were also responsible for the

administration of justice (ibid., p. 71). Although

they must be used with caution as not being

contemporary with the culture they describe,

later records such as the Irish tales show that

druids (for example Cathbad in the Táin Bó

Cuailgne: Kinsella 1969) were an integral and

important part of early Irish society. Australian

indigenous society similarly involved extended

periods of learning before initiation at various

levels, both for boys and girls. Certainly much

of this information related to religious matters

involving the Dreaming and the Law. These were

landscape history

matters that had to be kept secret by initiates,

while the Men’s Law and the Women’s Law

both had to be kept confidential from those

of the opposite sex (for the often-overlooked

importance of the ritual role of women in

Australian indigenous society, see, for example,

Bell & Ditton 1980). Also involved were matters

relating to an individual’s totemic animal and

the relationship that they should have with their

totem (pp. 126–7, 130), as well as with features

of the landscape that they ‘owned’, either through

their father or their mother. Fire itself was in fact

a significant totem, which people were expected

to consult before lighting it (p. 128). It does not

take a great deal of imagination to realise that

encompassed in the learning about all the features

of the landscape and how these places came

into being in the Dreaming was the knowledge

about how each of those natural features was

to be treated, including when each should be

burned. As Gammage says, ‘in 1788 who could

burn, how much, when and why, was intricately

regulated’ (p. 96).

Such information could be, and was, handed

on over considerable periods of time: it is

recognised that the environmental conditions

described in accounts of the Dreaming, such

as grassy plains where there are now deserts,

are in fact those pertaining in Australia during

the Pleistocene (Isaacs 1980, pp. 14–15), with

accounts of giant animals (Hancock 2012) that

all seem to have disappeared in Australia about

46,000 years ago and had certainly all gone by

the end of the Pleistocene (Molnar 2004, pp.50,

58, 80, 163). In the Blue Mountains to the west

of Sydney, Mount Wilson is famous for its lush

temperate rainforest with enormous tree ferns;

the rainforest is based on the rich volcanic

soils of the now-extinct Mount Wilson. The

local people have a legend, ascribed by them

to the Dreamtime, of how the earth blew up,

great flames filled the sky and rocks and debris

spread over the land (Isaacs 1980, pp. 29–31),

which can only represent a memory of the last

eruption of the Mount Wilson volcano. Indeed

it is just possible that the much-feared mythical

creature, the bunyip, may be a memory of the

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

carnivorous monitor lizard, Megalania prisca, the

largest terrestrial lizard known to have existed,

with a possible length of up to 7 metres (Molnar

2004, p. 118). It was similar to the Indonesian

ora (Varanus komodoensis), popularly known as

the Komodo dragon (ibid.), but double its size.

It had survived since the Early Pliocene, 4.5

million years ago, but disappeared about 30,000

years ago (ibid., pp. 104, 107), possibly as the

result of predation by the first humans to arrive

in Australia.

Obviously this book is of importance for

studies of the historical Australian landscape. It

is, however, of equal importance in two other

spheres. The first has already been acknowledged

by the number of prestigious awards that this

work has won to date, such as the Australian

Prime Minister’s Literary Award for History;

for farmers to accept and assimilate the lessons

taught by this book and adopt a totally new

approach to handling the Australian landscape.

It is not too late to retrieve some of the old

ways and thereby to reduce the dire effects of

landscape mismanagement, which are being

magnified by the effects of climate change on

the weather. Gammage admits that we can still

learn from 1788 (pp. 321–2), but that this is a

politically charged issue (p. 329), although he does

not acknowledge that one politically charged issue

relates to ‘contemporary Aboriginal attempts to

reclaim land precisely through the identification

of a deep history of inhabitation’ (Neale 2013,

p. 58).

It would be good to see a second book

by the author examining how many of the

original principles of indigenous landscape

management could be retrieved. This was first

suggested by Alfred Howitt in 1890 (pp. 322–3),

while in the 1920s some farmers copied the

old burning techniques (pp. 167, 177), but this

did not really take on. Gammage points out

that some of the traditional fire-management

techniques are beginning to be revived (pp. 56,

100). The results of regular cool fires, which

usually lasted only a day and did not go up into

the tree canopy (pp.159–60, 242), as against the

present infrequent hot fires (p. 27), meant that

77

before 1788 the modern disastrous bushfires

that devastate settlements, the wildlife and the

landscape and also kill people were very rare or

unknown. This was because the large quantities

of fuel that now feed infernos were not allowed to

build up (p. 160). Gammage quotes a Pitjantatjara

elder who explained that when

the country had been properly looked after …

it was not possible for such things as large-scale

bushfires to occur (p. 160).

The present-day recurrent population explo­

sions of mice, insects and kangaroos were

prevented and the hordes of flies that plague

modern life used to be kept under control

(pp. 81–4); Watkin Tench, writing just after the

First Settlement, commented that

insects, though numerous, are by no means, even

in summer, so troublesome as I have found them

in America, the West Indies and other countries

(1789, p. 76).

If a return to these conditions could be

effected, all Australians would welcome the end

of the famous ‘Australian wave’.

The second is the implications for studies

of Mesolithic landscapes throughout the world.

In the past it has often been assumed that

Mesolithic peoples, including those of Australia,

were conditioned more by their environment

than that their environment was conditioned by

them. Recently the extent to which Mesolithic

people were modifying their environment has

been recognised in Europe and elsewhere. For

example, in Europe they fired woodland both to

attract deer to the new growth at specific places

and to encourage recolonisation by hazel, whose

nuts are extremely nutritious and are frequently

found on Mesolithic sites (Cunliffe 2008, p. 89),

while similar sophisticated landscape manage­

ment has been identified in Eurasia (Harris

1991; 1996; 2010; Harris & Hillman 1989). The

Biggest Estate on Earth shows that, where such a

culture survived long enough to be recorded in a

literate era, it can be seen how considerable were

the modifications made to their environment by

a Mesolithic people. As Gammage points out

78

landscape history

(pp. 296–7), pre-European Australian culture

should really be classified not as hunter-gatherer,

but as hunter-gatherer-cultivator, as they were

harvesting crops whose location was known,

rather than randomly gathering (p. 148). He

claims that:

Only in Australia did a mobile people organise a

continent with such precision. In some past time,

probably distant, their focus tipped from land use

to land care. They sanctioned key principles: think

long term; leave the world as it is; think globally; act

locally; ally with fire; control population (p. 323).

This effectively sums up the approach of

the indigenous inhabitants of Australia, but we

only know about it in Australia because there

are records, written and pictorial, and surviving

descendants of these people. Were it possible to

go back in time to Mesolithic cultures in Europe

or elsewhere in the world, it might be the case that

there were similar extensive adaptations of the

landscape, as many of the indigenous practices

found in Australia would leave little or no trace

in the archaeological record.

The book itself is a pleasure to read, with an

extensive bibliography, good point size (11/15.5)

and attractive typeface (Caslon Classico Regular).

It is printed on good-quality paper, so that the

excellent colour illustrations, which demonstrate

the principles of templates better than written

descriptions can, are able to be placed wherever

appropriate in the text to complement points

being made. The only criticisms are that the

index is not sufficiently comprehensive and

some terms unfamiliar to European audiences

do not appear in the glossary (pp. xviii–xxx), for

example ‘lignotubers’, and that some references

would similarly be unknown and should have

been explained, for example what the Mabo and

Wik judgments (p. xxii) were or who the Aunungu

(p. 48) are. But overall Allen & Unwin are to be

congratulated on their part in this publication.

In a review of an outstanding work with

magnificent illustrations of Australia’s people

and landscape (Faull 1983), I concluded with

a quotation from Kath Walker, the indigenous

Australian poet:

We are nature and the past, all the old ways

Gone now and scattered.

The scrubs are gone, the hunting and the laughter.

The eagle is gone, the emu and the kangaroo are

gone from this place.

The bora ring is gone.

The corroboree is gone.

And we are going (1964, p. 25).

Nothing could be more apposite to the present

situation in Australia as described in The Biggest

Estate on Earth. We can only hope that Bill

Gammage’s book, together with other works such

as Back from the Brink (Andrews 2006), may go

some way to redress the balance and reverse the

disastrous way in which the Australian landscape

has generally been managed since 1788.

notes

1. Gammage refers throughout the book to the

indigenous inhabitants of Australia as ‘people’,

qualifying Europeans as ‘newcomers’ or ‘settlers’

(p. xix).

2. For the very different regimes for various plants see

pp. 121–2.

3. These three plates are reproduced courtesy of Bill

Gammage and Allen & Unwin. I should like to record

my thanks to Sam Redman of Allen & Unwin for

his assistance in the preparation of this article.

bibliography

Andrews, P., 2006. Back from the Brink (Sydney, Australia).

Bell, D., & Ditton, P., 1980. Law: the old and the new; Aboriginal

women in central Australia speak out (Canberra, Australia).

Benterrak, K., Muecke, S., & Roe, P., 1996. Reading the

Country: introduction to nomadology (Fremantle, Australia).

Brillaud, R., 2011. ‘Australie: le rêve s’incarne dans la

roche’, Les Cahiers de Science et Vie, 124 (August–

September 2011), pp. 37–41.

Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788

Blainey, G., 1975. Triumph of the Nomads; a history of ancient

Australia (Melbourne, Australia).

Brown-May, A., & Swain, S., 2005. The Encyclopedia of

Melbourne (Cambridge).

Clottes, J., 2001. La Grotte Chauvet: l’art des origins (Paris)

[trans. as Chauvet Cave: the art of earliest times, by P.

G. Bahn] (2003, Utah, USA)].

Cunliffe, B., 2008. Europe between the Oceans; themes and

variations: 9000 BC–AD 1000 (Yale, USA).

Faull, M.L., 1983. Review of J. Isaacs, Australian Dreaming,

in Landscape History, 5, pp. 83–5.

Flannery, T. F., 1994. The Future Eaters; an ecological history

of the Australasian lands and people (Sydney, Australia).

Gallop, R., 2003. The GI Diet: the glycemic index; the easy

healthy way to permanent weight loss (London).

Gammage, B., 2011. The Biggest Estate on Earth: how

Aborigines made Australia (Sydney, Australia).

Gautheron, A., 2011. ‘Quant l’esprit du beau vint aux

hommes’, Les Cahiers de Science et Vie, 124 (August–

September 2011), pp. 28–36.

Hancock, P., 2012. The Crocodile that Wasn’t: an eye-witness

account of extinct megafauna (Kindle edn).

Harris, D. R., 1991. Modelling Ecological Change: perspectives

from neoecology,palaeoecology and environmental archaeology

(London).

Harris, D. R. (ed.), 1996. The Origins and Spread of Agriculture

and Pastoralism in Eurasia (London).

Harris, D. R., 2010. Origins of Agriculture in Western Central

Asia: archaeological-environmental research in Turkmenistan

(Pennsylvania, USA).

Harris, D. R., & Hillman, G. C. (ed.), 1989. Foraging and

Farming: the evolution of plant exploitation (London).

Isaacs, J. (ed.), 1980. Australian Dreaming; 40,000 years of

Aboriginal history (Sydney, Australia).

Jones, R., 1969. ‘Fire-stick farming’, Australian Nat Hist,

16, pp.224–8.

Jones, R., 1980. ‘Cleaning the country: the Gindjingali and

their Arnhemland environment’, Broken Hill Propriety

J, 1980, part 1, pp.10–15.

Jones, R., 1985. ‘Ordering the landscape’, in Seeing the First

Australians, ed. I. Donaldson & T. Donaldson (Sydney,

Australia), pp.181–209.

Jones, R., 1995. ‘ Mindjongork: legacy of the firestick’,

in Country in Flames: Proceedings of the 1994 Symposium

on Biodiversity and Fire in North Australia, Biodiversity

Ser 3, ed. D. B. Rose (Canberra, Australia), pp.11–17.

Jones, R., & Meehan, B., 1989. ‘Plant foods of

the Gidjingali: ethnographic and archaeological

79

perspectives from northern Australia on tuber and

seed exploitation’, in Foraging and Farming: the evolution

of plant exploitation, ed. D. R. Harris & G. C. Hillman

(London), pp.120–35.

Kinsella, T. (trans.), 1969. The Tain; from the Irish epic Táin

Bó Cuailnge (London).

Lourandos, H., 1997. Continent of Hunter-Gatherers

(Cambridge).

Lourandos, H., & Ross, A., 1994. ‘The great

“Intensification Debate”: its history and place in

Australian archaeology’, Australian Archaeol, 39, pp.

54–63.

Lunt, I., 2013. ‘Location, location: the future of

environmental history’, Ian Lunt’s Ecological Research

Site (ianluntecology.com; posted on 17 February

2013).

Lycett, J., 1830. Drawings of the Natives and Scenery of Van

Diemens Land (London).

Maraszek, R., 2009. The Nebra Sky-disc, Kleine Reihe zu

den Himmelswegen, 2 (Halle, Germany) (English

version by B. O’Connor & D. Tucker).

Mathias, F., 2012. ‘Un ciel de fer et de bronze’, Les Cahiers

de Science et Vie, 129 (May 2012), pp. 27–30.

Meehan, B., & R. Jones, R., 1986. ‘Hunter-gatherer

diet: an archaeological perspective and ethnographic

method’, in Proceedings of the XIII International Congress

of Nutrition, ed. T. G. Taylor & N. K. Jenkins (London),

pp. 951–5.

Meller, H., 2002. ‘Die Himmelsscheibe von Nebra: ein

frübronzezeitlicher Fund von außergewöhnlicher

Bedeutung, Archäologie in Sachsen-Anhalt, 1, pp. 7‒20.

Meller, H., 2004. ‘Die Himmelsscheibe von Nebra’, in

Der geschmiedete Himmel: die weite Welt in Herzen Europas

vor 3600 Jahren, ed. H. Muller (Stuttgart), pp. 22–1.

Monbiot, G., 2013. Feral: searching for enchantment on the

frontiers of rewilding (London).

Molnar, R. E., 2004. Dragons in the Dust: the paleobiology

of the giant monitor lizard Megalania (Indiana, USA).

Neale, T., 2013. ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth, review by

Timothy Neale’, Arena Mag, 124 (May 2013), pp. 56–8.

Tench, W., 1789. 1788; comprising a narrative of the expedition

to Botany Bay and a complete account of the settlement at Port

Jackson, ed. T. Flannery (Melbourne, Australia, 1996).

Thomas, M., 2003. The Artificial Horizon; imagining the Blue

Mountains (Melbourne, Australia).

Walker, K., 1964. We are Going (Brisbane, Australia).

West, M. L., 2007. Indo-European Poetry and Myth (Oxford).