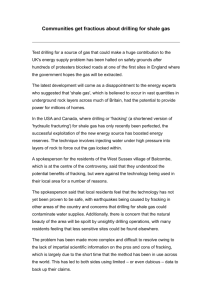

For the exclusive use of J. HUH, 2024. UV7567 Rev. Dec. 6, 2018 BE Oil One morning in late January 2015, Quentin Bell was facing some hard truths about the near-term prospects for his four-year-old oil company, BE Oil. The company had leased drilling rights on land in Colorado that would potentially generate six new shale oil wells. Just five months earlier, with oil prices near $100 per barrel, these wells appeared profitable. But in late 2014, oil prices plummeted to under $45 per barrel, dragging Bell’s anticipated drilling profits down with them. In fact, on that cold January morning, Bell had to determine if any of the six wells he had planned to drill were even worth starting. The only bit of good news was a slight anticipated increase in oil prices over the next six months. He hoped this would presage a more dramatic rise over time—otherwise, the market forces that drove oil prices might very well drive him out of business! The Economics of Shale Oil Drilling1 In 2003, a technological breakthrough combined horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), enabling development of natural gas shale. In 2009, the innovation extended into oil development and dramatically reshaped the US oil industry. Before 2009, shale oil production contributed minimally to the global oil supply, but the technological change resulted in an increase of US oil production from 5.4 million barrels per day in 2009 to 9.4 million barrels per day by the end of 2014. This increase represented over half of the overall increase in oil production globally. By early 2014, approximately 70 public oil and gas firms and more than 120 private firms were using fracking technology. In fact, by mid-2014, these companies were producing oil from over 200,000 oil wells across the five states that had shale oil fracking operations: Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Colorado, and New Mexico. Shale oil could be found in geologic formations up to two miles below the earth’s surface. To extract these reserves, firms first had to secure mineral rights from respective property owners. These oil leases allowed energy companies to drill and then frack shale formations to free oil from shale rock. Shale oil well drilling was somewhat unique relative to other types of oil extraction in that it required two distinct project steps. A company first drilled the well and then, at a later date, it fracked the well.2 To drill a well, the majority of firms in the industry rented a drilling rig from specialized service providers. It took between three days and three weeks to drill onshore wells. The average cost was about $3.5 million, but it varied greatly based on geology. Fracking typically occurred months after drilling and was usually performed by a specialized contractor, such 1 This section draws heavily from Erik Gilje, Elena Loutskina, and Daniel Murphy, “Drilling and Debt” (working paper, Darden School of Business, 2017). 2 In the parlance of the industry, to drill a well was to “spud” the well, and hydraulic fracturing was referred to as “completing” the well. Spudding involved drilling the well into the shale and inserting steel well casings and cement. This fictional case was prepared by Daniel Murphy, Assistant Professor of Business Administration, and Marc L. Lipson, Robert F. Vandall Professor of Business Administration. It was written as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright 2018 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved. To order copies, send an email to sales@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of the Darden School Foundation. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality, so please submit any errata to editorial@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. This document is authorized for use only by JAY HUH in Copy of Economic Analysis taught by Jun Auh, Georgetown University from Apr 2024 to Sep 2024. For the exclusive use of J. HUH, 2024. Page 2 UV7567 as Halliburton, Baker Hughes, or Schlumberger. Fracking took two or three days and cost about $3.0 million. As with drilling costs, this could vary greatly from well to well. Once a well was completed, the high starting pressure led to high initial production levels, which declined quickly as pressure was released. Consequently, the majority of output occurred in the first few months of production, and oil prices at the beginning of a well’s productive life were critical in determining the well’s economic returns. Oil Production and Costs for BE’s Six Possible Wells in Colorado Production costs for the six wells in Colorado were almost entirely related to drilling and fracking. The leasing payments had already be made and were therefore a sunk cost. Once oil was flowing, additional costs were negligible. From 2012 through 2014, the revenues to BE Oil from a well generally exceeded the costs. However, the drop in oil prices late in 2014 (see Figure 1) dramatically changed the landscape. While the decline in oil prices had also reduced the average cost of drilling and fracking, this cost reduction was not enough to make up for the drop in revenues. Furthermore, the cost of drilling each well depended on the accessibility of the oil. Wells containing oil further in the ground or within denser rock formations tended to have a higher up-front cost of extraction. Figure 1. Real price of oil in 2009 US dollars per barrel. Real Price of Oil (2009 USD per barrel) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 1990‐01‐01 1991‐01‐01 1992‐01‐01 1993‐01‐01 1994‐01‐01 1995‐01‐01 1996‐01‐01 1997‐01‐01 1998‐01‐01 1999‐01‐01 2000‐01‐01 2001‐01‐01 2002‐01‐01 2003‐01‐01 2004‐01‐01 2005‐01‐01 2006‐01‐01 2007‐01‐01 2008‐01‐01 2009‐01‐01 2010‐01‐01 2011‐01‐01 2012‐01‐01 2013‐01‐01 2014‐01‐01 2015‐01‐01 0 Source: All figures created by authors. This document is authorized for use only by JAY HUH in Copy of Economic Analysis taught by Jun Auh, Georgetown University from Apr 2024 to Sep 2024. For the exclusive use of J. HUH, 2024. Page 3 UV7567 Exhibit 1 summarizes the relevant data for the six possible wells and shows the anticipated drilling and fracking costs for each of them, along with the amount of oil each was expected to produce.3 All Bell needed to establish the economic value of a well was an estimate of oil prices at the time of completion. Given the expected lag between drilling and fracking any individual well, Bell estimated that it would be six months from the start of the process until oil began flowing. Thus Bell’s decision on each well, if he were to make a decision that January, would depend on oil prices anticipated for July 2015. Oil Prices The trajectory of oil prices was unclear as of the beginning of 2015. Futures prices predicted an appreciation of over 10% in the next six months (see Figure 2).4 Bell had to decide whether his expectations for changes in oil prices were aligned with the futures market. He also needed to determine how much BE Oil might lose if oil prices remained low. Bell was aware of research indicating that the recent drop in oil prices was due to both supply and demand factors.5 A surprise increase in oil production from US shale oil producers contributed to a glut in the global oil market. This supply-side effect was exacerbated by a slowdown in the world economy, which reduced demand for oil. The relative importance of each of these effects was debatable, but Bell was sure that similar global oil supply and demand factors would contribute to the future evolution of oil prices. Would Saudi Arabia and other members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) restrict their oil production to prop up prices? Would China continue its investments in oil-intensive infrastructure projects? Would global economic growth pick up over the next year? The answers to these questions would guide Bell’s expectations about the trajectory of oil prices, and hence, about the profitability of drilling and fracking each of his potential wells. 3 The cost estimates recognized any anticipated changes in the costs due to inflation or demand for equipment. Given that any changes in drilling and fracking costs related to oil prices occurred slowly and with a delay, Bell could reasonably treat those costs as independent of the oil price for his decisions on the Colorado wells. 4 Futures contracts were financial instruments that allowed traders to lock in a price at which to buy or sell a fixed quantity of the commodity on a predetermined date in the future. For example, the six-month futures prices specified the price at which traders of the six-month contract would buy or sell oil for delivery in six months’ time. Researchers and analysts often equated the current futures price with the expected future price. For more on futures prices and expected spot prices, see Ron Alquist and Lutz Kilian, “What Do We Learn from the Price of Crude Oil Futures?,” Journal of Applied Econometrics 25 (2010): 539–73. 5 Christiane Baumeister and Lutz Kilain, “Understanding the Decline in the Price of Oil Since 2014,” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 3, no. 1 (2016), 131–58. This document is authorized for use only by JAY HUH in Copy of Economic Analysis taught by Jun Auh, Georgetown University from Apr 2024 to Sep 2024. For the exclusive use of J. HUH, 2024. Page 4 UV7567 Figure 2. Percentage difference between futures price and spot price in the oil market. 30 20 10 0 ‐10 ‐20 2015m1 2014m9 2014m11 2014m7 2014m5 2014m3 2014m1 2013m11 2013m9 2013m7 2013m5 2013m3 2013m1 2012m9 2012m11 2012m7 2012m5 2012m3 2012m1 2011m11 2011m9 2011m7 2011m5 2011m3 2011m1 ‐30 Six‐Month Futures Price Summary Bell did not let the chill in the air dampen his spirits. Until recently, oil prices had been much higher. Bell hoped for a return to those levels. The long term, he believed, was bound to be brighter. But he did have to make a decision on the six wells in Colorado. Due to the specific nature of the leases, he either had to drill or give up the lease. And the decision had to be made in the next few weeks—before he would know for certain where oil prices would go. This document is authorized for use only by JAY HUH in Copy of Economic Analysis taught by Jun Auh, Georgetown University from Apr 2024 to Sep 2024. For the exclusive use of J. HUH, 2024. Page 5 UV7567 Exhibit 1 BE Oil Production, Costs, and Anticipated Revenue Projections for Wells Leased by BE Oil Well A B C D E F Barrels of Oil (thousands) 30 110 15 30 30 30 Drilling and Fracking Cost (millions of US dollars) 2.00 6.00 1.00 1.50 1.00 3.00 Anticipated Revenue at $50/Barrel Oil 1.50 5.50 0.75 1.50 1.50 1.50 Anticipated Revenue at $60/Barrel Oil 1.80 6.60 0.90 1.80 1.80 1.80 Anticipated Revenue at $70/Barrel Oil 2.10 7.70 1.05 2.10 2.10 2.10 Source: Created by authors. This document is authorized for use only by JAY HUH in Copy of Economic Analysis taught by Jun Auh, Georgetown University from Apr 2024 to Sep 2024.