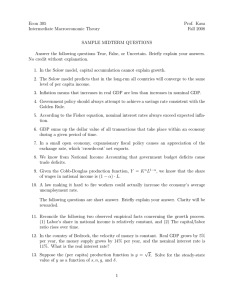

UVA-GEM-0207 Jan. 30, 2024 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies As Arturo Rodrigo rode the early-morning Metro-North train from Manhattan to Greenwich, Connecticut, in early 2023, his thoughts turned to prospects for the global economy.1 His task this morning was to decide which economies were poised for strong growth. Entering 2023, there was no dearth of negative news. In some sense, the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and incipient food and energy crises, made it difficult to imagine that one day there would again be high-flying economies. Headlines from the World Bank’s semiannual flagship publication Global Economic Prospects (GEP) had been decidedly downbeat for years, both on long-term prospects (the June 2021 report’s title: “Global Economy: Headed for a Decade of Disappointments?”) and near-term pain, with these less-than-encouraging words to open the January 2022 GEP:i The global recovery is set to decelerate amid continued COVID-19 flare-ups, diminished policy support, and lingering supply bottlenecks. The outlook is clouded by various downside risks, including new virus variants, unanchored inflation expectations, and financial stress. If some countries eventually require debt restructuring, the recovery will be more difficult to achieve than in the past. Climate change may increase commodity price volatility. Social tensions may heighten as a result of the increase in inequality caused by the pandemic. In June 2022, the GEP led with this: “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its effects on commodity markets, supply chains, inflation, and financial conditions have steepened the slowdown in global growth. One key risk to the outlook is the possibility of high global inflation accompanied by tepid growth, reminiscent of the stagflation of the 1970s.” But Rodrigo knew that gloom would not last forever and additional analysis was possible. He thought back two decades to the famous BRICs call and wondered how that analysis could inform his view of the present situation. BRICs, the now-famous acronym established in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, then head of global economic research for Goldman Sachs, referred to the strong growth potential in the economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China. O’Neill was in effect betting that the BRIC countries would grow faster than many others. He was correct. Over the years 2001 to 2014, Brazil, Russia, India, and China posted average annual growth rates of 5%, 6%, 8.7%, and 8.9%, respectively. By comparison, over the same period the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany each grew at only 2% per year. 1 The terms “country” and “nation” as used in this note do not in all cases refer to a territorial entity that is a state as understood by international law and practice, but rather cover well-defined, geographically self-contained economic areas that may not be states but for which statistical data are maintained on a separate and independent basis. This technical note was written by Francis E. Warnock, James C. Wheat Jr. Professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden Business School, and Kieren J. Walsh, Senior Assistant at KOF Swiss Economic Institute at ETH Zurich. Copyright © 2024 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved. To order copies, send an email to sales@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of the Darden School Foundation. This publication is protected by copyright and may not be uploaded in whole or part to any AI, large language model, or similar system, or to any related database. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality, so please submit any errata to editorial@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. Page 2 UVA-GEM-0207 Rodrigo, convinced he could learn from past episodes, decided to focus on the following questions: What are the economics behind BRICs? How do investors and managers identify the next BRIC countries (i.e., the next high-growth economies)? Could the economic frameworks underlying BRICs analysis provide some clarity after the fog of the COVID-19 pandemic and war in Europe? Identifying the Next High-Growth Economies The Solow growth model2 The Solow growth model forms the bedrock of economists’ thinking about long-term economic growth. The model has, at its core, two key pieces. The first is a long-run production function, which says that a country’s long-run output or productive capacity (Yfe) stems from three components: the amount of physical capital (𝐾) such as machinery, computers, or buildings; the size of its labor force (L); and the productivity (A) or efficiency with which labor and capital are combined, as in Equation 1: 𝑌 = 𝐾 𝛼 (𝐴𝐿)1−𝛼 , (1) where the parameter 𝛼, the “capital share,” is a number between 0 and 1 that represents the relative importance of capital versus labor in production.3 Holding either labor or capital constant, this production function exhibits diminishing marginal returns with respect to the other factor, meaning capital-scarce countries can get a larger boost from adding a little more capital. The second element is a capital accumulation equation (Equation 2): Δ𝐾 = 𝐼 − 𝛿𝐾 = 𝑠𝑌 − 𝛿𝐾. (2) The capital accumulation equation says that the change in the amount of capital (ΔK) is equal to new additions to the capital stock, which macroeconomists call investment (I), minus any depreciation of the existing capital stock (δK). Investment is itself generated by the new savings in the economy (the savings rate, s, times total output Y). The key diagram from Solow is Figure 1. Fully understanding it is beyond the scope of this note, but in a nutshell it tells us the following. First, note that everything is in per capita terms (k = K/L, y = Y/L). The horizontal axis is the amount of capital per worker (k). From any point on the horizontal axis, going up to the various curves tells you the amount of new investment per worker (sy), the amount of capital per worker lost to depreciation (δk), and output per worker (y). The model’s implications for economic growth can be divided into two time frames: the growth an economy will eventually settle into in the long run (this is called the steady state), and transitions toward a steady state (which can take a number of years). Specifically, the model evolves toward a steady state, a central tendency or long-run implication (denoted by asterisks in Figure 1) in which capital per worker and, hence, output per worker are constant. Per capita growth in the steady state must come from sustained technological progress (which shifts up the y curve, 2 Solow won the Nobel Prize for Economics for his work on growth theory. The original Solow growth article is Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 70, no. 1 (1956): 65–94. For details on the Solow growth model, see Kieran James Walsh, “Growth Theory,” UVA-GEM-0168 (Charlottesville, VA: Darden Business Publishing, 2018) or Felipe Saffie, “Determinants of Economic Growth,” UVA-GEM-0202 (Charlottesville, VA: Darden Business Publishing, 2022). 3 Economists call 𝛼 the capital share because in a model with the production function of Equation 1 and competitive capital and labor markets, 𝛼 is equal to the equilibrium amount of GDP earned by owners of capital. Page 3 UVA-GEM-0207 yielding higher and higher steady states), but economies can also grow strongly as they transition (over a number of years) from their current equilibrium to the steady state. Figure 1. The Solow diagram. Output and investmnet per capita 3 2.5 y 2 y* 𝛿𝑘 1.5 sy 1 0.5 k* 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Capital per capita (k) Source: Created by authors. The model provides stark predictions regarding economic growth. Specifically, it predicts that the countries that will grow quickly are those (i) catching up from below steady state and/or (ii) with rapidly increasing productivity.ii The second of these is easy enough to observe (as much as data allow us to observe actual phenomena). But the first requires a bit more thinking: For example, which countries are below steady state (and thus likely to grow quickly)? Economies below steady state might have (iii) been previously prosperous but have exogenously lost capital (e.g., from a war); (iv) had recent positive shocks to savings or new access to technology; or (v) experienced recent positive shocks to determinants of investment and technology, such as foreign direct investment (FDI) or declining debt service. Other growth factorsiii The Solow model leaves us with the notion that sustained per capita economic growth can come only from technological growth. Adding more capital won’t do it, because of diminishing returns. Sustained per capita economic growth has to come from technological growth. If we are willing to step outside the narrow confines of Solow’s original model, we notice a number of things that can fall under the umbrella of “technological growth.” Human capital. After Solow, many economists recognized that a narrow interpretation of capital wasn’t realistic, in part because human capital—the knowledge, skills, and training of individuals—is so important. As Page 4 UVA-GEM-0207 countries prosper, they also tend to invest more resources in people through improved nutrition, schooling, health care, and on-the-job training. This increase in human capital increases productivity. Population. The effect of population growth, not shown in the baseline model (Figure 1), is ambiguous. On the one hand, population growth will decrease the level of GDP per capita, because if we hold capital constant, then with more workers each has less capital to work with and hence produces less, albeit while increasing overall GDP (there are more people, each producing a little less, but overall output increases). Offsetting that effect is that innovations and hence productivity improvements often come from clusters, suggesting that more population can lead to increased productivity. Overall, population growth has a mechanical negative effect on per capita GDP but can spur productivity growth. Open-economy forces. The baseline Solow model is of a closed economy. Allowing for trading of goods and assets across borders can have two effects. One, the country now has access to foreign savings, which could increase s. Two, some foreign capital, such as FDI, might come with knowledge spillovers that can increase productivity. Government. The baseline Solow model assumes no government. Including government has two effects: One, governments can increase savings by running budget surpluses or decrease savings by running fiscal deficits. Two, governments can enable productivity growth and, hence, long-run living standards, by improving infrastructure (e.g., highways, bridges, utilities, dams, and airports); helping people build human capital through educational policies, work training, worker relocation programs, and health programs; incentivizing entrepreneurial activity (e.g., by reducing red tape); and encouraging research and development (e.g., by supporting scientific research, which has positive externalities). Of course, corruption and government inefficiencies can have the opposite effect. Institutions. Institutions can incentivize innovation and productivity growth, whereas hostile environments for innovation can harm productivity. The BRICs call Applying the lens of the Solow model and other growth factors to data available as of the end of 2000 provides insight into O’Neill’s BRICs call. Exhibit 1 shows year 2000 data for emerging-market economies (EMEs) with populations in excess of 30 million people.4 The growth potential of China is immediately evident. In 2000, it had high investment, second only to South Korea among large EMEs, and above-average human capital, as reflected in the education index.5 Yet China’s GDP per capita was behind economies that were comparable or worse on these measures (such as Thailand, Iran, South Africa, Colombia, and Egypt), suggesting that in 2000, China was well below steady state and primed to enter a high-growth “catching-up” period. India’s GDP per capita was even further behind (it was less than half of China’s), despite above-average investment. India’s human capital also lagged China’s, but it was above the levels in Iran and Pakistan, 4 There is no single way to identify which countries are EMEs, but it basically comes down to income levels (i.e., per capita GDP), size (nominal GDP, population), and trade and financial linkages with the rest of the world. See Rupa Duttagupta and Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, “Miles to Go,” International Monetary Fund (IMF), Finance and Development, Summer 2021, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/06/the-future-of-emergingmarkets-duttagupta-and-pazarbasioglu.htm (accessed Sept. 10, 2022) for the IMF’s methodology for identifying EMEs. 5 The human capital index (“Human Capital in PWT 9.0,” Groningen Growth and Development Centre, https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/docs/human_capital_in_pwt_90.pdf [accessed Sept. 10, 2022]) used in this note represents both years of schooling and quality of education. A high index value, like 3.7 for the United Kingdom in 2014, means people in that country generally receive high-quality education. A low index value, like 1.2 in Ethiopia in 2000, means the opposite. Page 5 UVA-GEM-0207 economies with higher output per person. Overall, with extremely low GDP per person, relatively high investment, and decent human capital, India also appeared to be below steady state. Brazil, while much wealthier than China and India in terms of GDP per capita in 2000, was substantially poorer than Mexico and Argentina. With above-average investment and average human capital, Brazil was, according to Solow factors, also poised to grow. In 2000, Russia had very high human capital, second only to South Korea among large EMEs, and slightly below-average investment. However, Russia was poorer in GDP per capita than Poland and Argentina, economies with lower human capital and only slightly higher investment. Therefore, Solow factors also indicated growth potential in Russia. High Growth Is in the Eye of the Beholder While growth in GDP per capita correlates with key measures of standards of living (and so is clearly important), why should a manager or investor care about GDP growth? The answer to this reasonable question depends on one’s perspective. Portfolio equity investors The returns to an arms-length portfolio equity investor depend on dividend yields and capital gains (and, for international investors, currency returns). While there are many drivers of each, from dividend payout policies to market fickleness or exuberance, both are ultimately tied to GDP growth. Dividends depend on earnings, which depend on sales and thus national income and aggregate demand. Capital gains and equity prices are more fickle, though ultimately tied to expectations of income and demand. Therefore, the armslength equity investor should indeed care about GDP growth. That said, how GDP growth translates into equity returns varies from country to country. One factor determining the “pass through” of GDP growth to equity returns is how much of a country’s growth comes from exchange-listed firms. Another factor is investor protection regulations, which determine how much of a listed firm’s growth arms-length investors actually get. Overall, as evidenced in Exhibit 2, stock market returns have been positively (but not perfectly) correlated with growth in many countries.6 Exporters GDP determines national income and hence demand, so it is natural for an exporter to assess possible recipient countries’ GDP growth prospects. Specific income levels and demographics of target clients, as well as the nature of trade agreements, are also important. Vertical foreign direct investors Vertical FDI is when a multinational corporation (MNC) owns a stage of production—often a supplier— in a foreign country. For example, a Japanese automotive company might own a supplier in South Korea that produces parts for the company’s Japan-based production facilities. While an MNC must consider many factors when deciding where to set up a vertical FDI operation (see, for example, Intel’s decision to produce in Costa 6 In the optimal corporate ownership theory of the home bias, investors are more likely to enter countries with poor governance with some protection, that is, as foreign direct investors rather than arms-length portfolio investors. See Bong-Chan Kho, René M. Stulz, and Francis E. Warnock, “Financial Globalization, Governance, and the Evolution of the Home Bias,” Journal of Accounting Research 47, no. 2 (2009): 597–635. Page 6 UVA-GEM-0207 Rica), vertical FDI primarily involves locating production where it is cheapest (broadly defined) and most efficient. GDP growth prospects in the vertical FDI location may not matter because the goods produced there are to be exported elsewhere (e.g., back to the company’s home country). Horizontal foreign direct investors Horizontal FDI, when the MNC owns a similar stage of production abroad, is a type of FDI in which the identification of high-growth economies is important (in addition to costs and regulations). Horizontal FDI occurs when it is cost effective to produce in a foreign country to serve that market (or export from there) rather than to produce at home. A number of factors determine whether to set up a horizontal FDI operation. On one side are revenue considerations that will depend on the location’s (and the neighboring countries’) growth prospects. Assume a country’s growth prospects are indeed promising. Then the MNC must decide whether to produce at home and export to that country or, taking into account costs and quality, to produce in that country (horizontal FDI). Producing in the country might reduce costs, and then the products can be sold in that country and perhaps other nearby countries. Cost considerations influencing this decision include trade restrictions (countries might have stricter restrictions on imports than on horizontal FDI), shipping costs (these would presumably be lower if closer to the ultimate buyer), and general costs of production. We note that over time the high-growth economy that is attractive for horizontal FDI might experience rising costs (e.g., wage increases that outstrip efficiency gains). See, for example, the increase in wages in China that pushed production to Vietnam and other countries with lower wages. Updated Analysis of Growth Prospects: The Next BRICs? Which countries are likely to be the next highfliers? Rodrigo appreciated the old analysis by Goldman Sachs, but wanted to canvas the literature to find additional, complementary ways of thinking about growth prospects. About a decade after O’Neill’s BRICs call, Ruchir Sharma, then head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, thought a broader approach was warranted. Sharma emphasized some direct Solow factors like income per capita and population growth, but also relied on experiential on-the-ground and “canary in the coal mine” leading indicators of factors only indirectly related to the Solow growth model.iv • Experiential competitiveness. Flexible labor markets, efficient business practices, and effective intermediate goods sourcing reduce costs, make firms more competitive, and allow economies to produce more output at given levels of capital and labor. Sharma gets a sense of an economy’s potential international competitiveness through comparing across countries the relative expensiveness of various products and services that he purchases when he travels. “A rule of the road: if the local prices in an emergingmarket country feel expensive even to a visitor from a rich nation, that country is probably not a breakout nation.”v • Inequality: Good billionaires and bad billionaires. In The Rise and Fall of Nations, Sharma writes, “Measuring changes in the scale, rate of turnover, and sources of billionaire wealth can help to provide some insight into whether an economy is creating the kind of productive wealth that will help it grow in the future. It’s a bad sign if the billionaire class owns a bloated share of the economy, becomes an entrenched and inbred elite, and produces its wealth mainly from politically connected industries.”vi Sharma argues that producing billionaires is an indication that an economy has the capacity to innovate, create wealth, and Page 7 UVA-GEM-0207 produce highly profitable companies. Lacking billionaires can reflect growth impediments such as excessively redistributive governments or institutional barriers to amassing wealth, which reduce incentives for work and innovation. However, Sharma continues, billionaires are not indicative of growth potential if their wealth predominantly stems from government connections, natural resource extraction, inheritance, or real estate. Furthermore, he claims that low turnover of billionaires, wealth concentration among billionaires, a high fraction of GDP going to billionaires, and billionaire wealth in government-controlled industries are signs of crony capitalism and corruption and thus suggest poor growth prospects. • Demographics, urbanization, and second cities. The density of cities allows for rapid diffusion of ideas and reduces the cost of moving labor and capital to their most productive uses. The ability of an economy to sustain and generate large cities is thus an indicator of growth potential. For Sharma, the key metric is the size of the “second city,” for example Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, Busan in Korea, St. Petersburg in Russia, and Kaohsiung in Taiwan. He argues that growth may be limited if, unlike in these instances, the population of the second city is less than one-third of that of the main city. On the other hand, low urbanization can signal future expansion. For example, part of the recent Chinese growth miracle was the result of policies allowing underutilized rural populations to migrate to cities and realize their potential productivity.7 • Infrastructure. The efficient movement of capital, intermediate goods, and labor requires infrastructure (e.g., quality roads, trains, and airports). Hence, while the level of investment is important, so is its composition. • The natural resource curse. Sharma emphasized two problems with growth driven by natural resource extraction. The first is the well-known concept of “Dutch disease”: commodities like oil are usually traded in foreign currencies (e.g., US dollars) from the perspective of emerging markets. Therefore, natural resource revenue leads to a glut of foreign currency, which causes appreciation of the domestic currency as domestic beneficiaries try to convert foreign currency into domestic currency in large quantities. This appreciation makes other industries less globally competitive. Second, abundant natural resources attract foreign and domestic capital and labor at the expense of other sectors. Both Dutch disease and the capital/labor shift can prevent long-term development and innovation in more sustainable industries robust to volatile global commodity prices and the depletion of resource reserves. Exhibits 3, 4, and 5 show recent data for a range of countries on direct Solow factors such as GDP per capita, population growth, savings, and the investment/GDP ratio; some measures emphasized by Sharma, such as ease of doing business rankings and infrastructure quality indexes (both of which indirectly affect the savings and technology Solow factors); and Sharma’s good/bad billionaires indicator.8 One could use such publicly available data and attempt to identify the next BRICs.9 7 This is the “Lewis turning point.” St. Lucian Nobel Prize–winning economist Arthur Lewis explained that an economy could achieve rapid growth through a surplus of low-wage farming labor fueling low-cost industrialization. The turning point arrives when the rural labor surplus is exhausted, and there is upward pressure on industrial wages (and thus costs). 8 The underlying data are available at “The World’s Billionaires,” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/ (accessed Nov. 16, 2018). For updated good/bad billionaire estimates, see Sharma’s May 14, 2021, Financial Times article, “The Billionaire Boom: How the Super-Rich Soaked up Covid Cash,” which shows that Mexico and Russia still have very high bad billionaires scores, and Taiwan, China, and South Korea have high good billionaires scores. 9 A shortcut is to simply look at the forecasts of experts. For example, the biannual IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) provides five-year real GDP forecasts for all countries; these projections, for selected EMEs, are also shown in Exhibit 3. Page 8 UVA-GEM-0207 Identifying the Next BRICs and the Next Fragile Five In early 2023, after almost three years of the COVID-19 pandemic and a year of war in Europe, there were severe concerns about incomes across much of the world. To Rodrigo, the entire world seemed headed for a period of sluggish economic growth and high inflation. But he knew “seemed” was not sufficient, so, having internalized the economics behind BRICs, as well as more updated analysis, he cleared his head and turned to analyzing data. Which countries are likely to be the next high-growth economies? Page 9 UVA-GEM-0207 Exhibit 1 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies Solow and the BRICs in Year 2000 GDP (in billions of US dollars) Argentina Bangladesh Brazil China Colombia DR Congo Egypt Ethiopia India Indonesia Iran Mexico Myanmar Nigeria Pakistan Philippines Poland Russia South Africa South Korea Sudan Tanzania Thailand Ukraine Vietnam Average 284 53 655 1,211 100 19 100 8 462 176 110 684 9 46 74 81 172 260 136 562 12 10 126 31 31 217 Real GDP Per Capita (in 2011 US dollars) 14,189 1,362 8,628 4,118 7,026 502 4,823 529 2,009 3,888 7,470 12,076 1,174 761 2,740 4,315 13,610 10,516 8,806 22,541 1,874 1,125 7,336 4,590 2,100 5,924 Gross Domestic Saving / GDP (in percentage) Investment / GDP (in percentage) Depreciation Rate (in percentage) Population Growth (in percentage) Human Capital Index 16 19 17 37 14 10 13 19 21 20 26 14 10 14 9 21 17 24 21 9 6 13 17 20 16 15 33 6 18 24 13 19 17 3.4 4.7 4.3 4.7 9.9 3.9 5.8 3.8 4.1 3.7 3.9 3.6 5.7 3.7 5.6 4.1 4.3 2.6 4.3 4.7 5.7 4.6 5.5 2.8 2.8 4.5 1.1 2.0 1.5 0.8 1.5 2.5 1.8 2.9 1.8 1.4 1.6 1.4 1.2 2.5 2.3 2.1 −1.0 −0.4 1.5 0.8 2.4 2.6 1.0 −1.0 1.3 1.4 2.7 1.6 2.0 2.2 2.2 1.6 2.0 1.2 1.8 2.2 1.7 2.4 1.5 1.5 1.6 2.4 3.0 3.2 2.1 3.2 1.4 1.5 2.2 3.1 2.0 2.1 26 31 37 22 39 16 16 18 39 19 35 27 10 31 25 26 24 Stock Market Capitalization (in billions of US dollars) 46 2 226 50 2 5 21 27 27 125 0 7 26 31 16 204 171 0 29 53 Real GDP growth, 2001–2006 (in percentage) 2.6 4.4 3.0 10.2 4.3 0.0 5.3 6.6 8.4 4.6 13.9 4.2 11.8 8.8 5.7 1.9 2.8 7.0 5.2 4.9 9.7 8.2 6.7 8.7 8.1 6.3 Note: The table shows Penn World Table 9.0 Solow factors from 2000 for emerging market economies (EMEs) with population in excess of 30 million. Real GDP and real capital per capita (in 2011 US dollars) are adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) to account for differences in the cost of living across countries. The human capital index, which reflects years and quality of schooling, ranges from 1 (low) to 4 (best). Nominal GDP, gross domestic savings, and population growth are from the World Development Indicators (WDI), https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed December 2017). Stock market capitalization is also from the WDI if end-2000 data is available; for countries for which end-2000 data are not available in the WDI (China, Colombia, Egypt, India, Nigeria, and Russia), it is the market capitalization deemed “investable” by the International Finance Corporation. Gross domestic savings are calculated as GDP less final consumption expenditure (total consumption). Source: Created by authors. Page 10 UVA-GEM-0207 Exhibit 2 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies Stock Market Returns and GDP Growth (2001–14) Annualized Percentage Change in Dollar Stock Index (2001–14) 25 COL 20 IDN 15 THA KOR MEX CZE ZAF 10 PHL AUS 5 JPN 0 ITA -5 0 CAN SWE USA DEU GBR FRA ARG CHE HUN POL PAK MYS BRA RUS TUR EGY IND CHN IRL 3 6 9 Annualized Real GDP Growth 2001–14 (percentage) 12 Notes: Real GDP is adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) to account for differences in the cost of living across countries. For each country, the dollar stock market return is the percentage change in the dollar MSCI price index. For country codes, see “Country Codes,” World Bank, https://wits.worldbank.org/WITS/wits/WITSHELP/Content/Codes/Country_Codes.htm (accessed Jan. 10, 2024). Data source: Penn World Table 9.0, https://www.msci.com/ (accessed Nov. 16, 2018). Page 11 UVA-GEM-0207 Exhibit 3 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies Recent Data on Growth Prospects (I) IMF LongTerm Real Growth Forecast (in percentage) Year Argentina Bangladesh Brazil China Colombia Egypt Ethiopia India Indonesia Mexico Nigeria Pakistan Poland Russia Serbia South Africa Thailand Ukraine Vietnam Average 2027 2.0 6.9 2.0 4.6 3.3 5.9 7.0 6.2 5.1 2.1 2.9 5.0 3.1 0.7 4.0 1.4 3.0 6.8 4.0 Investment / GDP (in percentage) GDP Per Capita (in US dollars) Population Growth (in percentage) 2019–21 average 15 32 17 42 19 15 31 28 32 20 28 13 18 21 22 14 23 14 31 23 2021 10,636 2,458 7,057 12,556 6,104 3,699 925 2,257 4,333 10,046 2,066 1,505 18,000 12,195 9,230 7,055 7,066 4,836 3,756 6,620 2021 0.9 1.1 0.5 0.1 1.1 1.7 2.6 0.8 0.7 0.6 2.4 1.8 −0.4 −0.4 −0.9 1.0 0.2 −0.8 0.8 0.7 Gross Domestic Saving / GDP (in percentage) 2019–21 average 20 26 17 45 13 6 21 28 33 23 27 6 24 30 16 17 31 9 34 22.4 Depreciation Rate (in percentage) 2019 3.5 4.0 4.8 5.2 3.8 5.4 4.7 5.7 4.2 3.9 3.4 7.5 5.1 3.4 4.1 5.2 6.3 2.6 5.4 4.6 Note: Gross domestic savings are calculated as GDP less consumption expenditure. Sources: Created by authors. Data are from the World Development Indicators, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/, except depreciation, which is from Penn World Tables 10.0, https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/productivity/pwt/, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) real GDP growth forecast, which is from the fall 2022 World Economic Outlook database, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weodatabase/2022/October (all accessed Jan. 2, 2023). Page 12 UVA-GEM-0207 Exhibit 4 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies Recent Data on Growth Prospects (II) Year Argentina Bangladesh Brazil China Colombia Egypt Ethiopia India Indonesia Mexico Nigeria Pakistan Poland Russia Serbia South Africa Thailand Ukraine Vietnam Average Ease of Doing Business Rank External Debt (as percentage of GNI) 2019 126 168 124 31 67 114 159 63 73 60 131 108 40 28 44 84 21 64 70 83 2021 51 21 39 15 56 37 27 20 36 48 18 38 28 68 41 43 70 39 39 CPI Inflation (as percentage) 2020–22 Average 54.3 5.8 7.0 1.8 5.3 6.2 26.9 6.2 2.7 5.7 16.4 10.6 7.4 8.0 5.7 4.9 2.2 10.9 2.9 10.0 Urbanization (as percentage) 2020 92 38 87 61 81 43 22 35 57 81 52 37 60 75 56 67 51 70 37 58 Infrastructure Human Capital Index Natural Resources Rents (as percentage of GDP) 2018 2.8 2.4 2.9 3.8 2.7 2.8 2.1 2.9 2.9 2.9 2.6 2.2 3.2 2.8 2.6 3.2 3.1 2.2 3.0 2.8 2019 3.1 2.1 3.1 2.7 2.6 2.7 1.5 2.2 2.3 2.8 2.0 1.8 3.5 3.4 3.5 2.9 2.8 3.3 2.9 2.7 2020 1.8 0.3 4.0 1.1 3.8 2.7 5.1 1.9 2.8 2.1 6.2 0.9 0.6 10.2 1.0 3.9 1.3 1.5 2.6 2.8 Notes: The infrastructure number is an index that measures “quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure (1 = low to 5 = high).” “Ease of Doing Business” ranks countries in the world from 1 (best) to 190 (worst). GNI is gross national income (GDP plus net factor payments). Sources: Created by authors. Data, current as of January 2, 2023, are from the World Development Indicators, except the human capital index, which reflects years and quality of schooling, ranges from 1 (low) to 4 (best), and is from Penn World Tables 10.0, and inflation, which is from the fall 2022 IMF WEO. Page 13 UVA-GEM-0207 Exhibit 5 Predicting the Next High-Growth Economies Good Billionaires, Bad Billionaires (The Rise and Fall of Nations) Total Billionaire Wealth / GDP Bad Billionaire Wealth / Total Billionaire Wealth Inherited Billionaires’ Wealth / Total Billionaire Wealth Brazil China India Indonesia Mexico Poland Russia South Korea Taiwan Turkey EME average 8% 5% 14% 7% 11% 2% 16% 5% 16% 6% 9% 5% 27% 31% 12% 71% 44% 67% 4% 23% 22% 31% 43% 1% 61% 62% 38% 0% 0% 83% 44% 57% 50% Australia Canada France Germany Italy Japan Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States AE Average 5% 8% 9% 11% 7% 2% 21% 15% 6% 15% 10% 45% 11% 5% 1% 3% 9% 5% 29% 25% 10% 14% 41% 47% 67% 73% 51% 14% 77% 62% 32% 34% 50% Country Note: AE = advanced economies; EME = emerging-market economies. Ruchir Sharma defines “bad” billionaires as those whose wealth stems from natural resource extraction, real estate, and government connections. Source: “The World’s Billionaires,” Forbes, March 2015, https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/ (accessed Nov. 16, 2018). Page 14 UVA-GEM-0207 Endnotes i The World Bank’s current “Global Economic Prospects” report is at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects (accessed Nov. 30, 2022). To access any past report from that page, click on Downloads (currently at upper right of page) and then choose Report Archive. ii See Charles I. Jones, “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population,” American Economic Review 112, no. 11 (2022): 3,489–527. iii For more on these growth factors, see the “Solow Outside the Box” appendix in Felipe Saffie, “Determinants of Economic Growth,” UVA-GEM0202 (Charlottesville, VA: Darden Business Publishing, 2022). iv See Ruchir Sharma, Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012). v Sharma, Breakout Nations. vi Ruchir Sharma, The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016).