The Globalization of World Politics An Introduction to International Relations 2

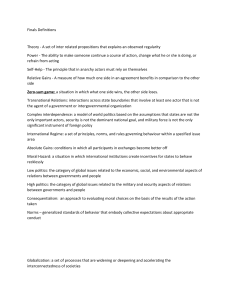

advertisement