Perkins, John - The new confessions of an economic hit man (2020, Langara College) - libgen.lc

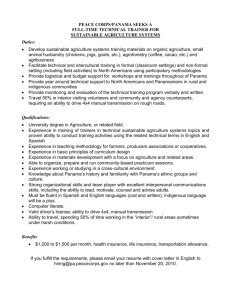

advertisement