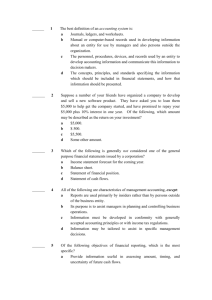

Budgeting A budget is an expression of an entity’s future plans. The budget is commonly used to set the level of activity for the period. Budgets commonly focus on a year. For an income account, variances indicate actual results were higher than the budget. Strategic plans commonly focus on a year.The budget is used by manufacturing entities and plans for the number of units the entity needs to manufacture, adjusted for expected levels. For an expense account, such as telephone, indicates actual results were higher than budgeted figures. The budget plans the profit for the period and summarises many other subbudgets, including sales and expenses. The anticipates expected future cash receipts and cash payments in a similar manner to a cash flow statement. Largely favorable variances between actual and budget need to be investigated further. Key steps in the budgeting process The budgeting process will commonly involve a series of steps, including: 1. consideration of past performance 2. assessment of the expected trading and operating conditions 3. preparation of initial budget estimates 4. adjustment to estimates based on communication with, and feedback from, managers 5. preparation of the budgeted reports and any sub-budgets 6. monitoring of actual performance against the budget over the budget period 7. making any necessary adjustments to the budget during the budget period Simons’s (2000, p. 81) three wheels of planning highlight the impact of decisions on each. The three wheels (cash, profit and return on investment) are interlocking and turn simultaneously. For example, the entity may be able to generate more sales in the coming year. However, will there be enough cash flow to acquire the inventory to support these sales or to acquire other necessary resources? Will the increased sales lead to higher profits, which will enable investment in assets that should lead to higher sales and more profits? The higher profit will lead to an increase in the return on owner’s investment. Different types of budgets Sales or fees budget - Serves as an important input variable for other budgets and is, therefore, often referred to as the ‘cornerstone’ of the budgeting process. The sales or fees budget is commonly used to set the expected level of activity for the budget period. The expected level of activity is an important consideration for many of the other budgets. This central role of the sales or fees budget is further underpinned in Simons’s three wheels of planning. (Operating) expenses budget - is commonly an aggregation from functional, sectional or departmental expense budgets, and also serves as an input variable to other budgets. For example, the expenses budget relating to the operation of the accounting department is used, along with other (e.g. marketing) departmental budgets, to build the overall operating expenses budget. It is sometimes simply called the ‘cost budget’. Production and inventory budgets - necessary in manufacturing environments for planning production levels and managing inventory levels. There are usually sub-budgets relating to direct materials, direct labour (if any) and indirect manufacturing overhead costs. Purchases budget - for both merchandising and manufacturing entities, which will set the required level of inventory/direct materials purchases based on data from the sales budget, and possibly from the production and inventory budgets as well. Manufacturing overhead budget - concerned with estimating the overheads or expenses associated with production activities. Budgeted statement of profit or loss - is essentially an aggregation of many of the other subbudgets, including the sales budget and the operating expenses budget. Cash budget - focuses on cash in the same way that the statement of cash flows does, and may be viewed as a statement of the expected future cash receipts and cash payments. Budgeted statement of financial position - shows what the entity’s financial position is expected to be as at the end of the period. Capital budget - deals with expenditure relating to long-term investments. (Capital budgeting is discussed in the capital investment chapter.) Program budget - focuses on costs associated with a specific program. This is a budget form commonly used in the government and not-for-profit sectors. The components of a budget Budgeting in planning and control The preparation of the cash budget is an important part of the planning process. Once prepared, the cash budget can be used to monitor cash performance, sometimes referred to as part of the control process. A cash budget prepared on a month-by-month basis is much more useful for this purpose than one prepared on a quarterly or yearly basis. Improving cash flow The cash budget identifies periods of expected cash shortages. In such situations, corrective action can restore the cash position. Cash inflow may be increased by: - improving the collections of cash from accounts receivable — perhaps the entity needs to review its invoicing and follow-up procedures, offer incentives for prompt payment or charge interest on overdue accounts - seeking ways to improve sales or fees — increasing advertising campaigns or changing features of the product/service to increase fees - reducing unnecessary inventory levels — discounting obsolete inventory will generate cash - arranging external finance — bank overdraft, accounts receivable factoring, invoice discounting - receiving an extra capital contribution from the owners or considering a change in ownership structure - selling excess non-current assets — a sale and leaseback arrangement may be more suitable Cash outflow may be reduced by: - cutting expenses by identifying areas of waste, duplication or inefficiency - making use of terms of credit — where purchases are made on credit, there is some benefit in using the full extent of the credit terms - keeping inventory levels to only what is required, as excess inventory ties up cash and often adds to storage and handling costs - deferring capital expenditures — it may be necessary to delay the acquisition of any noncurrent assets reducing the carbon footprint, which may reduce resource use and cash outflows Behavioural aspects of budgeting - The first relates to the style of budgeting process used by an organisation, such as the extent of participation by managers in the annual budget process. The second relates to the impact of the budget targets and plans on the behaviour, motivation and decision making of managers. Performance management Organisational performance is measured to ascertain the achievement of the organisation’s goals. The balanced scorecard framework implies that traditional financial performance measures are inadequate to capture the entire performance of the entity alone. There is a need to include both short-term and long-term measures, as well as financial and non-financial measures. Balanced scorecard framework The balanced scorecard framework is a performance framework that helps organisations focus on key performance indicators across four perspectives. The four perspectives are financial, customer, internal operations and innovation and improvement. The framework describes a need to balance financial measures with non-financial measures and to include both short-term and long-term measures. Balanced business scorecard Balanced scorecard for sustainability Divisional performance management Individual managers in charge of business units must set clear boundaries of responsibilities. Generally, business units can be classified into four different responsibility centres. - Cost centre — a division of an entity that is solely responsible for providing a product or service at minimal cost. Types of cost centres include manufacturing or service departments such as a manufacturing plant, a maintenance department and a personnel department. The performance of such managers is normally evaluated on cost factors. For example, a typical performance measure for a cost centre manager would include variance analysis (i.e. budgeted costs less actual costs). - Revenue centre — a division of an entity that is solely responsible for generating a target level of revenue. Revenue centre managers may be able to influence the price, market and volume of products. The manager of a marketing or sales division would be evaluated on the level of revenue achieved (budgeted revenue less actual revenue) and to some extent on customer awareness and satisfaction. - Profit centre — a division of an entity that has sole responsibility for both cost inputs and revenue and therefore the profit of a division. Depending on the scope of their responsibility, profit centre managers would be in charge of production costs/methods, suppliers, prices of products/services and markets. For example, a profit centre manager might be in charge of a geographical location or product line. These managers are evaluated on overall profit achieved through controlling costs and raising revenue (e.g. by comparing budgeted profits to actual profits) and by managing cash flows (measured by cash inflows less cash outflows). - Investment Centre — a division of an entity that is solely responsible for costs, revenues (and therefore profit) and investment in assets. An investment centre manager could be in charge of a geographically located division or a whole enterprise within a large corporation. This is the most sophisticated form of responsibility centre and a manager’s performance is assessed on the division’s overall contribution to the entity’s goal. Normally, this is based on comparing profit to the assets invested, but additional measures would be appropriate under a balanced scorecard framework. For example, variance analysis as well as cash flow considerations could be used - The organisational structure of an entity is designed to direct and control resources, and to clearly delineate the level of responsibility and authority of a division. These divisions could be functional, geographical or enterprise-based groups. - Responsibility centres are business units coordinated by a manager. They may take the form of a cost centre, a revenue centre, a profit centre or an investment centre. Divisional performance evaluation is designed to evaluate a division’s performance, achievement of goals, and contribution to the performance of the organisation as a whole. It also provides a guide for the pricing of products and services and a measure of the level of investment in each division Investment-centre performance evaluation measures Investment Centre o a division of an entity that is solely responsible for costs, revenues (and therefore profit) and investment in assets. An investment centre manager could be in charge of a geographically located division or a whole enterprise within a large corporation. This is the most sophisticated form of responsibility centre and a manager’s performance is assessed on the division’s overall contribution to the entity’s goal. Normally, this is based on comparing profit to the assets invested, but additional measures would be appropriate under a balanced scorecard framework. For example, variance analysis as well as cash flow considerations could be used Return on Income (ROI) = Profit/ Divisional Investment Using ROI as a performance indicator has the following advantages. o ROI is easy to use and understand. o It links profit with the investment base, thereby increasing awareness of asset management and discouraging overinvestment. o The relationship between assets held in the statement of financial position and the profit in the statement of profit or loss can be easily determined. Using ROI as a performance indicator has the following disadvantages. o ROI is a percentage measure, not a measure of absolute values. For instance, the ROI calculations above indicated that the specialty stores division was a better performer than the corporate division, yet the corporate division contributed $400 000 while the specialty stores division contributed $70 000. Therefore, ROI should not be used as the sole measure of performance. o ROI does not consider divisions that are different in size or type. Comparisons for performance evaluation are useful only if made between divisions of similar size and type. o Divisional managers can manipulate ROI by decreasing the investment base relative to the segment profit. For example, managers might delay investing in new equipment that would increase the investment base (the denominator) or purchase cheaper, substandard equipment. The use of ageing or suboptimal equipment might increase ROI in the short term but could be detrimental to performance in the long term. o ROI use could result in suboptimal decision making. Managers might reject an investment opportunity because it could decrease overall ROI. For example, assume the specialty stores division has an opportunity to expand into another geographical market with an investment requirement of $50 000 and an expected segment return of $12 500. The expected ROI of this expansion would be 25 per cent and the existing ROI for the corporate division of 31.1 per cent would be reduced to 30 per cent by this new investment. The reduction in the ROI might make the manager reluctant to take on the investment even though it would have a positive impact on the company overall. The disadvantages discussed above result from ROI being a short-term performance measure. There is a need to include long-term performance measures in combination with the ROI when assessing performance. Residual income (RI) = Profit before tax − (Required rate of return × Investment) o Using RI as a performance indicator has the following advantages. It minimises the suboptimal decision-making that could result from using ROI. A manager would take on a new investment opportunity if the dollar return was greater than the charge for the extra capital invested. The charge for capital can vary across divisions based on the risk of the venture being pursued in each division. o Using RI as a performance indicator has the following disadvantages. It can still encourage short-term decision-making. The required rate of return or a suitable charge for capital may not be easy to determine. Accounting transactions 4.5 Distinguish between personal transactions and business transactions. Illustrate with five examples of each. Business transactions involve an exchange of goods between the business entity and another entity. Examples of business transactions include the following: • payment of rent of a building • purchase of goods from a supplier • sale of goods on credit to a customer • payment of tax to the Australian Taxation Office • payment of wages to employees. Personal transactions of the owner, partners or shareholders do not involve an exchange of goods between the business entity and another entity. They involve a transaction between the individual and another entity. An example of a non-business transaction could include the following: • payment of personal health insurance • purchase of a family car • taking the family on an overseas holiday paid for in cash • sale of personally owned shares in Coles Myer • purchase of tickets to the AFL Grand final by the individual. It is important to keep business transactions separate from those of the owner(s), as the entity's financial reports should reflect the entity's performance, position and cash flow only and not include personal assets. If payments for these types of transactions are made out of business funds, the amount should be treated as a reduction in the owner’s equity (drawings), and it is therefore recorded as a business transaction. Concept of duality - The concept of duality means that every business transaction will have a dual effect on the accounting equation. The equation always stays balanced. For example, the purchase of a motor vehicle on credit will mean that the motor vehicle asset will be increased, and the supplier (accounts payable) will be increased. - Transaction analysis: o read the transaction o identify the cash effect o identify the nature of the transaction o check that the equation balances Accounting concepts 5.4 Discuss whether the following statements are true or false. a. The terms ‘accounts receivables and ‘debtors mean the same thing. True — the terms ‘debtors or ‘accounts receivable’ describe entities/individuals that owe money, supplies or services to the entity. b. The statement of profit or loss is a financial statement that shows the entity's assets and liabilities as at a point in time. False — the statement of profit or loss shows the income and expenses of an entity for a period of time, hence it is titled ‘Statement of profit or loss for the X month period ending...’. On the other hand, the statement of financial position is a financial statement that shows the assets, liabilities and equity of an entity as at a point in time. Hence it is titled ‘Statement of financial position as at ...’. c. Mr Startup invests his own cash and van to start a business. This transaction will increase the equity and assets of the business. True — the owner’s contribution of cash and a vehicle increases the assets of the entity. The dual effect of this is to recognise that the owner has contributed equity to the business, and the equity in the statement of financial position increases by the same amount as the assets have increased. 5.7 List three essential characteristics necessary to consider an item either as an asset or a liability. An asset is defined as ‘a present economic resource controlled by the entity as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity’. The three essential characteristics of an asset are: 1. a present economic resource 2. the resource must be controlled by the entity 3. the resource must be as a result of a past event. A liability is defined as ‘a present obligation of the entity to transfer an economic resource as a result of past events. The three essential characteristics of a liability are: 1. a present obligation 2. to transfer an economic resource 3. a result of past events. Ratios for Financial statement analysing Chapter 8: 8.4 Users of financial statements are interested in an entity’s future profitability, asset efficiency, liquidity and capital structure. Describe the ratios that would be of interest to users and the purpose of computing these ratios. Profitability In analysing an entity’s future profitability, users normally look at return on equity (ROE), return on asset (ROA. and profit margin. ROE indicates how much return an entity is generating for owners for each dollar of the owner’s fund invested in the entity, ROA reflects an entity’s ability to generate return from asset investments, and profit margin ratio compares an entity’s earnings to its sales revenue. Users are interested in assessing an entity’s past profitability through profitability ratios, as it will shape the users’ expectations as to the entity’s future profitability. Assets efficiency Asset turnover, days inventory and days debtors ratios are commonly used to assess an entity’s asset efficiency. Asset turnover ratio measures an entity’s overall efficiency in generating income/sales from its asset investments. Days inventory and days debtors indicate the average period of time it takes for an entity to sell its inventory and collect money from its trade debtors. By computing the asset efficiency ratios, users would be able to make evaluations from past decisions to see how efficient the entity manages its asset investments, which are mostly in inventory and accounts receivable, to generate income. Current ratio In terms of liquidity, users are interested in current ratio, quick asset ratio and cash flow ratio. The current ratio measures an entity’s current assets in dollar amount as per dollar of current liabilities, the quick asset ratio indicates how many dollars of current assets available (excluding inventory) to pay for a dollar of current liabilities, and the cash flow ratio indicates the entity’s ability to cover its current liabilities from operating activity cash flow. It is important for users to analyse an entity’s liquidity position, as liquidity is a measure of the entity’s ability to pay for its debts when they fall due. Capital structure When assessing an entity’s capital structure, users would be interested in calculating debt to equity ratio, debt ratio and equity ratio. Debt to equity ratio reflects the proportion of using external financing (debt) to internal financing (equity) in asset investments. Debt ratio and equity ratio show the dollars of debt and equity respectively per dollar of asset. Capital structure ratios depict the proportion of debt to equity funding, and are useful when assessing an entity’s long-term viability. Creditor ratios 8.7 Identify what ratios a credit provider would be particularly interested in. A credit provider would be particularly interested in an entity’s ability to pay interest as it falls due and to repay the principal of the borrowings at maturity date. Hence, a credit provider would be interested in solvency ratios that provide information about debt-paying ability as follows. Debt ratio. Debt ratio measures the percentage of total assets provided by creditors. The higher the ratio, the higher the risk that the entity will not be able to repay its debts. If an entity already has a high level of borrowings, the bank lender may be hesitant to lend more to the entity as the entity’s may not have the ability to service the debt. A credit provider needs to assess the riskiness of the lender and ensure that the return (e.g. interest charged. is commensurate with the firm’s risk profile. Interest coverage ratio. This ratio measures an entity’s ability to meet interest payments as they fall due. A credit provider would be interested to know if the entity’s profit is able to comfortably cover interest payments due. As interest is paid in cash, a cash coverage ratio (e.g. cash flow from operating activities divided by net interest) may be more useful. Debt coverage ratio. Debt coverage ratio measures how long it will take to repay the existing long-term debts using cash flows from operating activities. A credit provider may be hesitant to lend more to the entity if it takes longer than average for the entity to repay the loan, as it indicates that the entity might have problems in the long term to repay the debts. Limitations of ratio analysis 8.13 Discuss three limitations of ratio analysis as a fundamental analysis tool. Ratio analysis relies on financial numbers in financial statements. Accordingly, the quality of the ratios calculated is dependent on the quality of the entity’s financial statements. The quality may be affected by inadequate disclosures and lack of details in financial statements and/or a firm’s accounting policy choices and estimations. Many of the ratios that are calculated rely on the asset, liability or equity numbers reported in the statement of financial position. This statement reflects the financial position of an ongoing entity at a particular date and may not be representative of the financial position at other times of the year. Financial statements are historical statements reflecting past transactions. Often, the past is a good guide to the future; however, the use of information outside financial statements also needs to be considered when forming predictions as to an entity’s future financial health.