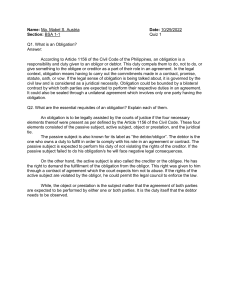

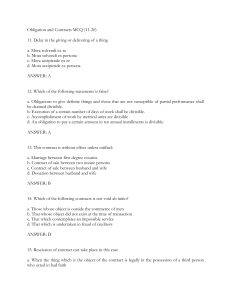

SAN BEDA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW SY. 2020 – 2021 OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS REVIEWER SPARTA NOTES Cruz, Kyla Raine M. Mambuay, Mujaheed Abdul Jamil S. Makilan, Hannah Angelica C. Marasigan, Joanne Catherine A. Suyat, Gian Jeruie F. Tang, Francesca Marie C. Valenzuela, Diane Faie O. 1C Page | 1 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS TITLE I – OBLIGATIONS CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1156. An obligation is a juridical necessity to give, to do or not to do. (n) Obligations – • • • • • A tie of law which binds us, according to the rules of our civil law, to render something (Institute of Justinian) A legal relation between one person and another, who is bound to the fulfillment of a prestation which the former may demand of him (Manresa). The juridical necessity to comply with a prestation (Sanchez Roman). A juridical necessity to give, to do or not to do (Civil Code of the Philippines). A juridical relation whereby a person (called the creditor) may demand from another (called the debtor) the observance of a determinate conduct, and in case of breach, may obtain satisfaction from the assets of the latter (Justice J.B.L. Reyes) Essential Elements of Obligation: 1. 2. 3. 4. A juridical tie (or vinculum juris) Object or prestation Active subject (obligee or creditor) Passive subject (obligor or debtor) Juridical Tie or Vinculum Juris • • • Legal relationship or tie Essentially binds the parties to the object of the obligation (or prestation), by virtue of which the debtor is bound to the creditor to fulfill a determinate prestation. The efficient cause or the very reason for the existence of the obligation. Object of the Obligation Prestation: • • The object of obligation The particular conduct required to be observed by the obligor (debtor) and which can be demanded by the oblige (creditor). Object of the obligation vs subject matter of the contract Object of the obligation The object is always a particular conduct of the obligor called the prestation. • Subject matter of the contract The object or subject matter may either be a thing, a right, or a service. A prestation may consist either in giving, doing or not doing. Obligation to give vs Obligation to do Obligation to give Compliance with it is intimately connected with the thing to be delivered. Also called real obligation. Obligation to do Compliance with the obligation is incumbent upon the person obliged. Also called personal obligation. Reason for distinction: for purposes of determining the remedies available to the obligee in case of breach of obligation. • • In obligation to give, the obligee may avail of the remedy of compelling the obligor to give or deliver what is due. In obligation to do, the obligor may not be compelled against his will, to perform the act that he is bound to render. Reason: Obligation to do may not be resorted because it amounts to involuntary servitude – an act prohibited by the Constitution. Active and Passive Subjects Obligee (creditor) Obligor (debtor) Has the right to Bound to perform demand the the prestation. prestation. Page | 2 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Denominated as the active subject because he is the one who has the power to demand the performance of the prestation. The obligor is referred to as the passive subject because his action is dependent of the action of the creditor. Illustration: • • The enumeration is exclusive. An obligation enforced on a person, and the corresponding right granted to another, must be rooted in at least one of these five sources. Makati Stock Exchange, Inc. vs Campos • A practice or custom is not a source of legally demandable or enforceable right. The obligee may choose either: The sources may be classified generally as: 1. To exact fulfillment of the prestation from the obligor 2. To condone the obligation 3. To remain inactive for a certain period of time sufficient enough to extinguish the obligation by way of prescription. Legal Sanctions Juridical Necessity • • Implies the existence of legal sanctions that may be imposed upon the obligor (debtor) in case of breach of the obligation. These legal sanctions do not include the imprisonment of the debtor for mere nonpayment of the debt or non-performance of an obligation. Reason: Section 20, Article III of the 1987 Constitution provides that no person shall be imprisoned for debt of non-payment of a poll tax. Article 1157. Obligations arise from: (1) Law; (2) Contracts; (3) Quasi-contracts; (4) Acts or omissions punished by law; and (5) Quasi-delicts. (1089a) Sources of Obligations Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. Emanating from law 2. Emanating from private acts The sources of obligations emanating from private acts may either arise from: 1. Licit acts (contracts and quasi-contracts) 2. Elicit acts (delicts and quasi-delicts) • • Contracts – are result of bilateral actions of the parties because it requires consent. Quasi-contracts, Delicts, Quasi-Delicts – are products of the unilateral action of the debtor. Obligations emanating from law vs Obligations emanating from acts Obligations emanating from law It is the law which creates the obligation in view of the organization of juridical institutions and the social interest. Obligations emanating from acts There is always some individual act which gives rise to the obligation, and the law intervenes only to provide a sanction or prevent an injustice. Article 1158. Obligations derived from law are not presumed. Only those expressly determined in this Code or in special laws are demandable, and shall be regulated by the precepts of the law which establishes them; and as to what has not been foreseen, by the provisions of this Book. (1090) Page | 3 Obligations arising from law Example: 1. The obligation of tax payers to pay taxes in accordance with existing tax statues. 2. The obligation of the spouses to render mutual help and support in accordance with the provisions of the Family Code of the Philippines. • • • In contracts, quasi-contracts, delicts, and quasi-delicts, the source of the obligation is the act or acts of the parties, which may either be unilateral or bilateral, and the aw merely recognizes its existence, regulates it and sanctions the same. Obligations derived from law are not presumed. Only those expressly determined in the Civil Code or in special law are demandable. Article 1159. Obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the contracting parties and should be complied with in good faith. (1091a) Implied contract vs quasi-contract Implied contract quasi-contract Requires consent of Not predicated on the parties. consent, being a product of unilateral act. Note: in contract law, this principle is known as the obligatory force of contract, which presupposes the existence of a valid and enforceable contract. Article 1160. Obligations derived from quasicontracts shall be subject to the provisions of Chapter 1, Title XVII, of this Book. (n) Obligations arising from quasi-contract (Obligatio Ex Cuasi Contractu) Definition: Article 2142. Certain lawful, voluntary and unilateral acts give rise to the juridical relation of quasi-contract to the end that no one shall be unjustly enriched or benefited at the expense of another. • Obligations arising from contracts Contract – a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some services. • The obligation is not contractual in nature in the absence of the element of consent, whether implied or express. Neither is the obligation based on delict or quasi-delict, if the act which gives rise to it is not unlawful. Basis: nemo cum alterius detrimento locupletari protest – no man shall enrich himself at the expense of another. Consent is the essence of a contract. Characteristics of Quasi-Contract: Implied Contract – arises where the intention of the parties is not expressed, but an agreement in fact, creating an obligation, is implied or presumed from their act, or where there are circumstances which, according to the ordinary course of dealing and the common understanding of men, show a mutual intent to contract. 1. It arises from a lawful act. 2. It arises from a voluntary act. 3. It arises from a unilateral act. • It is based on the presumed will or intent of the obligor dictated by equity and by principles of absolute justice. Some of the principles are the following: 1. It is presumed that a person agrees to that which will benefit him. Page | 4 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 2. Nobody wants to enrich himself unjustly at the expense of another. 3. We must do unto others what we want them to do unto us under the same circumstances. Forms of Quasi-contract • • Forms of quasi-contract are not exclusive. Basis: Article 2143. The provisions for quasicontracts in this Chapter do not exclude other quasi-contracts which may come within the purview of the preceding article. authorized by the owner. The owner must have been aware of the gestor’s intervention. • • A. Negotiorum Gestio • • • Arises when a person, called the officious manager or gestor, voluntarily takes charge of the agency or management of the business of property of another which has been neglected or abandoned, without any power from the latter. It was developed to govern the management of an absent person’s affairs. The owner of the business or property must either be physically absent or has failed to appoint a proper agent to administer the business or property because the concept explicitly covers abandoned or neglected property or business. • On the part of the officious or gestor • • • • Negotiorum Gestio vs Implied Agency Negotiorum Implied Agency Gestio It is necessary that Contractual in the gestor must not nature, there being have been tacitly present the element of consent, In order for the juridical relation negotiorum gestio to arise, it is necessary that the gestor must acted in good faith. He must have acted for another out of a sense of duty to render assistance to those in need and not for his own sake or his own interests. In order for the gestor to be entitled to reimbursement, it is also important that he must acted on behalf of the owner but with the intention of demanding indemnification for expenses he incurred. Obligations Created in Negotiorum Gestio Requisites: 1. A person voluntarily assumes the agency o management of the business or property of another. 2. The property or business is neglected or abandoned. 3. There is no authorization from the owner, either expressly or impliedly. 4. The assumption of agency or management is done in good faith. although given tacitly. The owner knew of the gestor’s intervention and yet did not interpose any objection. • Once the gestor intervenes, he cannot just quit and abandon the property or the business. The law requires him to continue with the agency or management until the termination of the affairs and its incidents or until the owner appears and substitutes him in such management. If the owner suffers damage by reason his fault or negligence, he is liable to pay damages to the owner. The gestor may delegate to another person all or some of his duties but he shall remain liable to the owner for the acts of the delegate. In case there will be two or more gestors, their responsibility to the owner shall be solidary, unless the management was assumed to save the thing or business from eminent danger, in which case the liability shall be merely joint. The gestor is not liable for any loss or damage to the property or business by reason of fortuitous event. Page | 5 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Exception: 1. Undertakes risky operations which the owner was not accustomed to embark upon. 2. Prefers his own interest to that of the owner. 3. Fails to return the property or business after demand by the owner 4. Assumes the management in bad faith 5. Manifestly unfit to carry on the management, except when the same was assumed to save the property or business from eminent danger. 6. Prevents, by his intervention, a more competent person from taking up the management, except when the same was assumed to save the property or business from eminent danger. • In case the gestor has entered into contracts with the third persons in the performance of his duties as such, he is the one personally liable to the third persons with whom he dealt with, even though he acted in the name of the owner. Expectations: 1. The owner has ratified the management, either expressly or tacitly. 2. When the contract refers to the things pertaining to the owner of the business. Note: in the case of ratification of the management of the business, the effects of an express agency will be produced, even if the business may not have been successful. The relationship between the gestor and the owner will cease to be that of negotiorum gestio, but will become contractual in nature. expressly ratified, in any of the following situations: a. If the owner enjoys the advantages of the officious management. b. If the management had for its purpose the prevention of an imminent and manifest loss, although no benefit may have been derived. c. Even if the owner did not derive any benefit and there has been no imminent and manifest danger tot the property or business, provided that the gestor has acted in good faith and the property or business is intact ready to be returned to the owner. Extinguishment of Negotiorum Gestio 1. Repudiation of the officious management by the owner. 2. Putting an end to such officious management by the owner. 3. Death, civil interdiction, insanity or insolvency of the owner or the gestor. 4. Withdrawal from the management by the gestor, but without prejudice to his liability for damages should the owner suffer damages. SOLUTION INDEBITI Basis: based on the ancient principle that no one shall enrich himself unjustly at the expense of another. Definition: Article 2154. If something is received when there is no right to demand it, and it was unduly delivered through mistake, the obligation to return it arises. (1895) Application: On the part of the owner The owner of the business or property becomes liable to the gestor for: 1. Obligations incurred in his interest. 2. Necessary and useful expenses; and 3. Damages suffered by the gestor in the performance of his duties, although the officious management may not have been 1. A payment is made when there exists no binding relation between the payor, who has no duty to pay, and the person who received the payment. 2. The payment is made through mistake, and not through liberty or some other cause. • It is presumed that there was mistake in the payment if something which had never been Page | 6 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 due or had already been paid has delivered; but he from whom the return is claimed may prove that the delivery was made out of liberty or for any other cause. 4. That the plaintiff has no other action based on contract, quasi-contract, crime, or quasidelict. Difference: Exception: payment by reason of mistake in the construction or application of a doubtful or difficult question of law may come within the scope of (solution indebiti). Solution Indebiti vs In Rem Verso Accion in Rem Verso Definition: Article 22. Every person who through an act of performance by another, or any other means, acquires or comes into possession of something at the expense of the latter without just or legal ground, shall return the same to him. Accion in Rem Verso Considered merely an auxiliary action, available when there is no other remedy on contract, quasi-contract, crime, or quasidelict. The obligation of the debtor to return is based on law. Similarities: • Accion in Rem Solution Indebiti Verso Based on the principle of unjust enrichment which is essentially contemplates payment when there is no duty to pay, and the person who receives the payment has no right to receive it. There is unjust enrichment when: • 1. A person is unjustly benefited. 2. Such benefit is derived at the expense of or with damages to another. Unjust enrichment – exists when a person unjustly retains a benefit to the loss of another, or when a person retains a money or property of another against the fundamental principles of justice, equity, and good conscience. Elements of Accion in Rem: 1. The defendant has been enriched 2. The plaintiff has suffered loss 3. That the enrichment of the defendant is without just or legal ground. Solution Indebiti The obligation to return is based on quasi-delict. Mistake is an essential element. If there is mistake in the payment, the available remedy is an action to recover the undue payment based on the principle of solutio indebiti and the availability of this remedy on quasi-contract shall preclude any recovery based on accion in rem verso. In accion in rem verso, while the defendant is enriched without just or legal ground, such enrichment must not be by reason of any mistake in payment by the plaintiff. Obligation of Debtor in Solutio Indebiti • A creditor-debtor relationship is created under a quasi-contract whereby the payor becomes the creditor who then has the right to demand the return of payment made by mistake, and the person who has no right to receive such payment becomes obligated to return the same. The recipient of the payment is exempt from the obligation to restore if the following requisites are present: 1. Be believed in good faith that the payment was being made of a legitimate and subsisting claim. Page | 7 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 2. He destroyed the documents, or allowed the action to prescribe, or gave up the pledges, or cancelled the guarantees of his right. • • • The debtor, should he acted in good faith in accepting the undue payment, shall be likewise be liable to pay interest if the sum of money is involved, or shall be liable for fruits received or which should have been received (by the creditor) if the thing produces fruits. The debtor shall likewise be answerable for any loss or impairment of the thing from any cause, and for damages to the person who delivered the thing (the creditor (, until it is recovered. Should the debtor acted in good faith, he shall be responsible for the impairment or loss of the same or its accessories and accession insofar as he has thereby been benefited. If he has alienated the thing, his obligation is only to return the price or to assign the action to collect the sum. Other forms of Quasi-Contract 1. Giving of Legal Support and Payment of Funeral Expenses • • • If such support is given by a stranger without the knowledge of the person obliged to give support, the former has a right to claim reimbursement from the latter, unless it appears that the stranger gave it out of piety and without intention of being repaid. The obligation to refund the amount is not by virtue of law, but based on quasi-contract. When the person to be supported is either an orphan, or an insane or other indigent person, or a minor child and the person obliged to give support unjustly refuses to give it, any third person who furnished support to the needy individual has a right to claim reimbursement from the person obliged to give it. Acts of a good Samaritan Example: when a person is injured or become seriously ill by reason of an accident or other cause and he is treated or helped while he is not in a condition to give consent to a contract, he is liable to pay for the services of the physician or other person aiding him, unless the service has been rendered out of pure generosity. Third Person Pays Debt or Taxes of Another Anyone who is constrained to pay the taxes of another shall be entitled to reimbursement from the latter. Acts of Consideration of General Welfare When the government, upon the failure of any person to comply with health or safety regulations concerning property, undertakes to do the necessary work, even over his objection, he shall be liable to pay the expenses. Article 1161. Civil obligations arising from criminal offenses shall be governed by the penal laws, subject to the provisions of article 2177, and of the pertinent provisions of Chapter 2, Preliminary Title, on Human Relations, and of Title XVIII of this Book, regulating damages. (1092a) Obligations arising from delicts (Obligatio Ex Delicto) Basis of Civil Liability in Crimes or Delicts Article 100. Civil liability of a person guilty of felony. Every person criminally liable for a felony is also civilly liable. (Revised Penal Code) A crime has dual character: 1. As an order 2. As an offense against the private person injured by the crime unless it involves the crime of treason, rebellion, espionage, contempt and others wherein no civil liability arises on the part of the offender either because there are no damages to be compensated or there is no private person injured by the crime. • Civil liability exists in a crime only if there is a private offended party who suffered damage. Page | 8 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • In cases where there are no private persons injured by the crime, such as treason, rebellion, espionage, contempt and the likes, no civil liability arises on the part of the offender. Criminal liability will give rise to civil liability only if the same felonious act or omission results in damage or injury to another and is the direct and proximate cause thereof. Effect of Acquittal of the Accused 2 kinds of Acquittal: 1. On the ground that the accused is not the author of the act or omission complained of. • This instance closes the door to civil liability, for a person who has been found to be not the perpetrator of any act or omission cannot and can never be held liable for such act or omission. Basis: The extinction of the penal action does not carry with its extinction of the civil action. However, the civil action based on delict shall be deemed extinguished if there is a finding in a final judgment in the criminal action that the act or omission from which the civil liability may arise did not exist. (Last paragraph, Section 2, Rule 111 of the 2000 Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure). • • • Applies only to a civil action arising from crime or ex delicto and not to civil action arising from quasi-delict or culpa aquiliana. Civil liability arising from quasi-delict or culpa aquiliana, the same will not be extinguished by an acquittal, whether it be on ground f reasonable doubt or that accused was not the author of the act or omission complained of. An acquittal or conviction in the criminal case is entirely irrelevant in the civil case based on quasi-delict or culpa aquiliana. 2. Based on reasonable doubt on the guilt of the accused. • Even if the guilt of the accused has not been satisfactorily established, he is not exempt from civil liability (based on the crime) which may be proved by preponderance of evidence only. Basis: Article 29. When the accused in a criminal prosecution is acquitted on the ground that his guilt has not been proved beyond reasonable doubt, a civil action for damages for the same act or omission may be instituted. Such action requires only a preponderance of evidence. Upon motion of the defendant, the court may require the plaintiff to file a bond to answer for damages in case the complaint should be found to be malicious. If in a criminal case the judgment of acquittal is based upon reasonable doubt, the court shall so declare. In the absence of any declaration to that effect, it may be inferred from the text of the decision whether or not the acquittal is due to that ground. (Civil Code) • • • A person acquitted of a criminal charge is not necessarily free from civil liability because the quantum of proof required in criminal prosecution (beyond reasonable doubt) is greater than that required for civil liability (mere preponderance of evidence). In order to completely free from civil liability, a person’s acquittal must be based of fact that he did not commit the offense. If the acquittal is based merely on reasonable doubt, the accused may still be held liable since this does not mean he did not commit the act complained of. The acquittal will not bar a civil action in the following cases: 1. The acquittal is based on reasonable doubt as only preponderance of evidence is required in civil action. 2. Where the court declared the accused’s liability is not criminal but only civil in nature. Page | 9 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 3. Where the civil liability does not arise from or is not based upon the criminal act of which the accused was acquitted. Article 1162. Obligations derived from quasidelicts shall be governed by the provisions of Chapter 2, Title XVII of this Book, and by special laws. (1093a) Does Article 29 of the Civil Code require filing of a separate civil action to recover the civil liability ex delicto in case of acquittal based on reasonable doubt? Obligations arising from quasi-delicts (Obligation Ex Cuasi Delicto) Ans: No. In the case of Padilla vs Court of Appeals, the court may acquit an accused based on reasonable doubt and, at the same time, order the payment of civil liability already proved in the same case without need for separate civil action. Definition: Article 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no preexisting contractual relation between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter. (1902a) Reason: this will prevent the needless clogging of court dockets and the unnecessary duplication of litigation. Rule of Implied Institution Rule: when a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for the recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged is deemed instituted with the criminal action, unless the offended party waives the civil action, reserves the right to institute it separately or institutes the civil action prior to the criminal action. However, it must be made clear that the civil action which is deemed instituted with the criminal action is one which is based on the delict. Effect of Death of Accused Pending Appeal • • • • As to criminal liability, Article 89, par.1 of the RPC is clear that the same is totally extinguished by his death As to civil liability on the same crime, People vs Bayotas explained that the civil liability arising from the crime or delict (or civil liability ex delicto) is also extinguished. The death of the accused prior to final judgement terminates his criminal liability and only the civil liability directly arising from and based solely on the offense committed, i.e. civil liability ex delicto. The claim for the civil liability survives notwithstanding the death of the accused, if the same may also be predicted on a source of obligation other than delict, i.e., civil liability based on quasi-delict. Requisites: 1. Damage suffered by the plaintiff. 2. Fault or negligence of the defendant. 3. Connection of cause and effect between the fault or negligence of defendant and the damage incurred by the plaintiff. Reason: man should subordinate his acts to the precepts of prudence and if he fails to observe them and causes damage to another, he must repair the damage. Scope of Quasi-delict Crime vs Quasi-delict Crime Affects the public interest. Penal Code punishes or corrects the criminal act. Delicts are not as broad as quasidelicts because the former are punished only if there is a penal law clearly covering them. Quasi-delict Affects only private concern. Civil Code, by means of indemnification, merely repairs the damages. Quasi-delict includes all acts in which any kind of fault or negligence intervenes. Page | 10 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Similarities Crime Quasi-delict An act or omission characterized by fault or negligence is committed, that such act or omission is unlawful, and that the same causes damage or injury to another. Effect of Pre-existing Contractual Relations • • Is the concept of quasi-delict limited only to fault or negligence not punishable by law? Ans: No. In the case of Barredo vs Garcia and Almario, “same negligent act causing damages” may produce civil liability arising from crime under Article 100 of the RPC or create an action fro quasi-delict under Articles 2176 to 2194 of the Civil Code. • Air France vs Carrascoso • The existence of a contract between the parties does not bar the commission of a tort (quasi-delict) by one against the other and the consequent recovery of damages, therefore, when the act that breaks the contract is also of a tort. • When an act which constitutes a breach of contract would have itself constitutes the source of a quasi-delictual liability had no contract existed between the parties, the contract can be said to have been breached by tort, thereby allowing the rules on tort to apply. In situations where there is already a contract between the parties prior to the commission of the quasi-delict and such commission is the very reason for the breach of the contract, the injured party may recover under contract or quasi-delict. If the injured party opts to recover under contract, the source of obligation is the contract itself and not the negligence committed during the performance of the obligation already in existence. If the recovery is based on quasi-delict, it is the negligence itself which is the source of the obligation. In every commission of a crime through negligence (or culpa), the private offended party may recover civil liability either under delict or quasi-delict. What if the crime is committed through dolo? Will the Barredo ruling also apply? Ans: In Elcano vs Hill, the concept of quasi-delict includes voluntary and negligent acts which may be punishable by law. Article 2176 covers not only acts committed with negligence, but also act which are voluntary and intentional. • • The term “fault” in Article 2176 covers deliberate and intentional acts, while “negligence” refers to cases of omission of the required diligence (or unintentional) When the quasi-delict is committed through negligence or culpa, it is referred to as culpa aquiliana or culpa extra-contractual. Prohibition Against Double Recovery • The law provides for a prohibition against double recovery from both delict and quasidelict. The existence of a contract between the parties prior to the occurrence of the fault or negligence precludes the commission of quasi-delict. The pre-existing contract between the parties may bar the applicability of the lay on quasidelict, the liability may itself be deemed to arise from quasi-delict, i.e. the acts which breaks the contract may also be a quasidelict. • • • Basis: Article 2177. Responsibility for fault or negligence under the preceding article is entirely separate and distinct from the civil liability arising from negligence under the Penal Code. But the plaintiff cannot recover damages twice for the same act or omission of the defendant. (n) Page | 11 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Culpa Aquiliana (Culpa extra-contractual) vs Culpa Contractual Culpa Aquiliana Culpa Contractual Its source the Breached of negligence of the contract is premised torfeasor upon the negligence in the performance of a contractual obligation. The negligence or The negligence or culpa is substantive culpa is considered and independent, as an accident in which of itself the performance of constitutes the an obligation source of an already existing – obligation between the vinculum exists persons not independently of formerly connected the breach of the by any legal tie. voluntary duty assumed by the parties when entering into the contractual relation. The negligence The mere proof of should be clearly the existence of the established contract and the because it is the failure of its basis of the action. compliance justify, prima facie, a corresponding right of relief. Liability of employer for an act or omission of his employee 1. Recovery under Contract of Carriage • The liability devolves upon the employer because the driver is not a party to the contract of carriage and may not be held liable under the contract. 2. Recovery Under Delict or Crime • • The employee is directly and primarily liable, while the employer is subsidiary liable. If the cause of action against the employee is based on delict, it is not correct to hold the employer jointly and severally liable with the employee. Before the employer’s subsidiary liability is enforced, adequate evidence must exist establishing that: 1. They are indeed the employers of the convicted employees. 2. They are engaged in some kind of industry. 3. The crime was committed by the employees in the discharge of their duties. 4. The execution against the latter has no been satisfied due to insolvency. • The employer cannot relieve himself of liability of proving that he exercised all the diligence of a good father of a family in the selection and supervision of his employees. This is because of the very nature of the obligation. 3. Recovery under Quasi-delict • • The offended party may choose to recover only from the employee for the latter’s negligence pursuant to Article 2176 of the Civil Code, or directly from the employer pursuant to the latter’s vicarious liability under Article 2180 of the Civil Code, or from both. The employer may also be held liable under the doctrine of vicarious liability or imputed negligence. Doctrine of vicarious liability • A person who has not committed the act or omission which caused damage or injury to another may nevertheless be held civilly liable to the latter either directly or subsidiarily under certain circumstances. • Whenever an employee’s negligence causes damage or injury to another, there instantly arises a presumption juris tantum that there was negligence on the part of the employer, either in the selection of the employees or the supervision over him after the selection. • The theory of presumed negligence is clearly deducible from the last paragraph of Art. 2180 which provides that the responsibility therein mentioned shall cease if the employers prove that they observed all the diligence of a good father to prevent damages. Page | 12 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CIVIL AND NATURAL OBLIGATIONS Article 1423. Obligations are civil or natural. Civil obligations give a right of action to compel their performance. Natural obligations, not being based on positive law but on equity and natural law, do not grant a right of action to enforce their performance, but after voluntary fulfillment by the obligor, they authorize the retention of what has been delivered or rendered by reason thereof. Some natural obligations are set forth in the following articles. actually rendered ineffective. Though not enforceable through a court action, can possibly produce a certain legal effect. Within the domain of law being a true obligation capable of producing legal effects. Civil Obligations • One which gives a right of action to compel its performance. • One which provides for a legal sanction in case of its breach. • The creditor is authorized to invoke the power of the State, through the courts, either to compel its performance or to demand any other alternative relief. Basis of Natural Obligation: Article 1424. When a right to sue upon a civil obligation has lapsed by extinctive prescription, the obligor who voluntarily performs the contract cannot recover what he has delivered or the value of the service he has rendered. Natural Obligations • One which does not grant a right of action to enforce its performance, but after voluntary fulfillment by the debtor, it authorizes the retention of what has been delivered or rendered by reason thereof. • This kind of obligation does not provide for legal sanction in case of non-performance. • The debtor may not be compelled by the coercive power of the State, exercised through our courts, to perform this kind of obligation because its performance depends exclusively upon his conscience. • It grants the creditor the right to retain what has been delivered by reason thereof after the same has been voluntarily fulfilled by the debtor. Distinguished from purely moral obligations Natural Obligation Purely Moral Obligation There is a juridical There is no juridical tie which could give tie. a cause of action but because of some special circumstances is Not possible to produce legal consequences. Within the domain of the morals. Note: When the civil code classifies obligations into civil and natural only, does not recognize the existence of a purely moral obligation. Reason: a purely moral obligation is not within the domain of the law since it is incapable of producing any legal effect. Legal Effects of Natural Obligation 1. The creditor is authorized to retain what has been delivered or rendered by reason of the voluntary fulfillment of natural obligation. 2. A natural obligation may again be covered into a civil obligation, either by reason of novation or when it has been made the subject matter of a contract of guaranty, pledge or mortgage. Requirement of Voluntary Fulfillment • The creditor acquires the right to retain what has been delivered or paid to him only in cases where the fulfillment of a natural obligation is voluntary on the part of the debtor. • In order for such fulfillment to be considered voluntary, it is not sufficient that the act be done spontaneously or free from any coercion. • It is also necessary that the act be free from any error or mistake. Page | 13 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Basis: Article 1956. No interest shall be due unless it has been expressly stipulated in writing. (1755a) Article 1957. Contracts and stipulations, under any cloak or device whatever, intended to circumvent the laws against usury shall be void. The borrower may recover in accordance with the laws on usury. (n) delivered or the value of the service he has rendered. 2. When a third person pays a debt which had already prescribed, he cannot demand reimbursement from the debtor if the payment was made without the knowledge or against the will of the latter. When action to enforce obligation has failed • Payment of monetary interest is allowed only if: 1. There was an express stipulation for the payment of interest. 2. The agreement for the payment of interest was reduced in writing. • • If the borrower pays interest when there has been no stipulation therefore, the provisions of the Code concerning solutio indebiti or natural obligations shall apply, as the case may be. The term “voluntarily fulfillment” in Article 1423 requires that the performance of the obligation must not only be spontaneous but must also be free from error or mistake. Example: if the defendant voluntarily performs the obligation after the action for its enforcement has failed, he cannot demand the return of what he has delivered or the payment of the value of the service he has rendered. When payment of deceased’s debt exceeds inheritance • Instances of Natural Obligations • The enumeration of natural obligations in Article 1424 to 1430 is not exclusive. Basis: Last sentence of Article 1423 when it says tat “some natural obligations are set forth in the following articles.” When debt has prescribed • When the action to enforce a civil obligation has failed, it is plain that the civil obligation ceases for another action to enforce the same obligation is already barred by the principle of res judicata. • With respect to monetary debts left by the decedent, the rule is that the heir shall be liable thereto only up to the extent of the value of the property he received from the decedent. The obligation to pay the debt up to the value of the inherited property is a civil one, while the obligation to pay the excess is only natural. Payment of Legacy in Void will • A will is void and shall be disallowed if the formalities required by law have not been complied with. When the right to sue upon a civil obligation has lapsed by extinctive prescription, the obligation ceases to be civil one and becomes natural obligations. Example: 1. Obligor voluntarily performs the contract; he cannot anymore recover what he has Page | 14 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CHAPTER 2 Nature and Effect of Obligations Article 1163. Every person obliged to give something is also obliged to take care of it with the proper diligence of a good father of a family, unless the law or the stipulation of the parties requires another standard of care. (1094a) Article 1164. The creditor has a right to the fruits of the thing from the time the obligation to deliver it arises. However, he shall acquire no real right over it until the same has been delivered to him. (1095) Real and Personal Obligations Real Obligations Personal Obligations It consists of giving Consists either in doing or not doing. Compliance is Compliance is connected with the incumbent upon the thing to be delivered person obliged. Obligation to give • Involves the delivery of a movable or immovable thing in order to create a real right, or for the use of the recipient, or for its simple possession, or in order to return to its owner. If the obligation to give consists in the delivery of a specific o determinate thing. It is particularly designated or physically segregated from all others of the same class, If the obligation consists merely in that of delivering any member of the genus or class. Only the genus or class has been determined, without the same being designated and distinguished from all others of the same class. Positive and Negative Personal Obligations Positive Personal Obligations Obligation to do Negative Personal Obligations Obligation not to do Accessory Obligations in Determinate (Specific) Obligations Three accessory obligations obligations in determinate 1. The obligation to preserve the thing to be delivered. 2. The obligation to deliver the fruits, if the creditor is already entitled to them. 3. The obligation to deliver the accessions and accessories. Duty to Preserve Specific Thing Due Obligation to do • Includes all kind of work in service. Obligation not to do • Consists in abstaining from such acts. Specific and Generic Obligations Specific Obligations Determinate obligation Generic Obligations Indeterminate obligation General Rule: the only way by which the debtor may be able to comply with his determinate obligation is by delivering the exact thing which is due. Basis: Article 1244. The debtor of a thing cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be of the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due. Note: accessory obligation finds no application to an obligation to give an indeterminate thing. Page | 15 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Degree of Diligence Required • The debtor in indeterminate obligation is bound to observe the proper diligence of a good father of a family in taking care of the thing to be delivered. Meaning: The law refers to the diligence required of a reasonable prudent person. General Rule: The bonus pater familias rule applies in determining the diligence required of the debtor in fulfilling his obligation to preserve the determinate thing due. Exception: this rule does not apply when the law and the stipulation of the parties requires another standard of care. Example: when the debtor is already guilty of delay or if he has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest. Reason: because the debtor shall already be responsible for fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. Basis: If the obligor delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest, he shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. Can the parties agree on a standard of care lower than that of the good father of a family? Ans: The parties can validly agree even on a standard of care lower than that of the bonus pater familias, i.e. an agreement providing only for slight care. • It shall be lawful for the parties to require a degree of diligence higher than that of then good father of a family, such as extraordinary care and even for liability by reason of fortuitous event. Duty to deliver fruits When Creditor Acquires Rights Over Fruits In determinate obligations, is the debtor bound to deliver the fruits of the determinate thing due? Ans: Yes, if the creditor already acquired rights over fruits. • It is necessary to determinate the exact time when a creditor acquires a right over the fruits of the determinate thing due. When is the obligation to deliver the determinate thing due deemed to have risen? Ans: In obligation arising from law, quasi-contracts, quasidelicts, and delicts, the specific provision applicable to them determine the time when the obligation to deliver arises. In obligation arising from contracts, arises upon the perfection of the contract because as such time, the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law. When the Creditor Acquires Real Right Personal Right The power of one person to demand of another, as a definite passive subject, the fulfillment of a prestation to give, to do, or not to do. • Real Right The power belonging to a person over a specific thing, without a passive subject individually determined, against whom such right may be personally exercised. The creditors acquire a real right over a thing only upon its delivery and this principle applies not only to the specific thing due, but also to its fruits. Page | 16 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Basis: non nudis pactis, sed traditione dominia rerum transferentur (the owner of thing is transferred not by mere agreement, but by tradition or delivery. • Prior to the delivery, the right of the debtor over the determinate thing due and its fruits is merely a personal right – which is simply the right to demand from the debtor the delivery of yhe determinate thing due and its fruits, in proper cases. accessions and accessories, even though they may not have been mentioned. (1097a) Article 1167. If a person obliged to do something fails to do it, the same shall be executed at his cost. This same rule shall be observed if he does it in contravention of the tenor of the obligation. Furthermore, it may be decreed that what has been poorly done be undone. (1098) Duty to Deliver the Accessions and Accessories Basis: Article 1166. The obligation to give a determinate thing includes that of delivering all its accessions and accessories, even though they may not have been mentioned. Accessories – refer to those things which, being intended for the ornamentation, use or preservation of another or more importance, have for their object the completion of the later for which they are indispensable or convenient. Article 1168. When the obligation consists in not doing, and the obligor does what has been forbidden him, it shall also be undone at his expense. (1099a) Remedies of Creditor in Case of Breach of Obligation Breach of Determinate Obligation • Example: Key in case of house, machinery in case of factory. Accessions – includes cases of natural accessions, such as alluvium, avulsion and formation of islands, and cases of industrial accessions, in the form of building, planting and sowing. Article 1165. When what is to be delivered is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition to the right granted him by article 1170, may compel the debtor to make the delivery. If the thing is indeterminate or generic, he may ask that the obligation be complied with at the expense of the debtor. If the obligor delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest, he shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. (1096) • The debtor cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due. In case of breach of the obligation, the creditor can compel his debtor to make the delivery. Basis: When what is to be delivered is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition to the right granted him by article 1170, may compel the debtor to make the delivery. • • • • • The creditor can also recover damages against the debtor The right to compel delivery and to recover damages are cumulative and not alternative. If the source of obligation is contract, the creditor has an alternative remedy aside from an action for specific performance. In proper cases, he may cause the rescission of the contract. In case of breach of the obligation, in addition to his right recover damages. Article 1166. The obligation to give a determinate thing includes that of delivering all its Page | 17 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Breach of Generic Obligations • • • Compel the performance of the obligation at the expense of the obligor. The delivery shall be done by someone else and not by the debtor himself, but the expenses that will be incurred in performing the obligation shall be borne by the latter. The creditor may compel the debtor himself to make the delivery. Note: the action to compel is still denominated as one for specific performance even if what is to be delivered is a generic thing. • • • • Whether the thing due is determinate or generic, the action to compel delivery is for specific performance. The only difference being that in determinate obligations the debtor may not compel the creditor to accept a different one other than what is due, while in generic obligations, the delivery of any member of the genus or class will suffice. If the debtor does not make the delivery, the obligation may be performed by someone else at his expense. The creditor still has the right to recover the same from the debtor by virtue of the basic rule on liability for damages by reason of non-fulfillment of obligations expressed in Article 1170 of the Civil Code. Breach of Positive Personal Obligations • • An obligation to do is considered breached not only when it is not performed, but also when the performance is poor or in contravention of the tenor of the obligation. In either case, the debtor cannot be compelled, against his will, to execute the act which he bound himself to do. Basis: Involuntary Servitude – Section 18, Article III of the Constitution. Alternative mode of fulfilling the obligation in case the debtor refuses to comply with his undertaking: 1. The law authorizes the creditor to have the act executed by himself or by another at the expense of the debtor, in addition to his right to recover damages. 2. The law grants the creditor to demand for the undoing of what has been don, at the expense of the debtor (if done poorly) Breach of Negative Personal Obligations • • An obligation not to do is considered breached when the debtor does what has been forbidden him. The remedy of the creditor is to demand for the undoing of what has been done, at the debtor’s expense, in addition to his right to recover damages. Article 1169. Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation. However, the demand by the creditor shall not be necessary in order that delay may exist: (1) When the obligation or the law expressly so declare; or (2) When from the nature and the circumstances of the obligation it appears that the designation of the time when the thing is to be delivered or the service is to be rendered was a controlling motive for the establishment of the contract; or (3) When demand would be useless, as when the obligor has rendered it beyond his power to perform. In reciprocal obligations, neither party incurs in delay if the other does not comply or is not ready to comply in a proper manner with what is incumbent upon him. From the moment one of the parties fulfills his obligation, delay by the other begins. (1100a) Article 1170. Those who in the performance of their obligations are guilty of fraud, negligence, Page | 18 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 or delay, and those who in any manner contravene the tenor thereof, are liable for damages. (1101) debtor is fulfilling the obligation by not doing what is forbidden him. Requisite: When is there a breach of obligation? • • • There is a breach not only when it is not performed, but also when it is performed in contravention of its tenor. if the no-fulfillment of the obligation is not due to the debtor’s fault but by reason of fortuitous event, the debtor is not liable. If the non-fulfillment of the obligation is due to the fault of the debtor because he is guilty of delay, fraud, negligence, or he contravenes in any manner the tenor thereof, he becomes liable to the creditor for damages. 1. That the obligation be demandable and already liquidated. 2. That the debtor delays performance. 3. That the creditor requires the performance judicially or extrajudicially. • • A debtor is deemed to have violated his obligation to the creditor from the time the latter makes a demand. Absent any demand from the obligee, oral or written, the effects of default do not rise and the obligor does not incur delay, as a rule. Exceptions to Requirement of Demand Delay or Default (Mora) • Is the non-fulfillment of the obligation with respect to time. Three kinds of mora: 1. Mora solvendi – default on the part of the debtor to perform, which may either be: a. Mora solvendi ex re – referring to obligations to give. b. Mora Solvendi ex persona – referring to obligations to do. 2. Mora Accipiendi – default on the part of the creditor to receive. 3. Compensatio Morae – default of both parties in reciprocal obligations. 1. When the obligation expressly so declares 2. When the la expressly so declares. 3. When from the nature and the circumstances of the obligation it appears that the designation of the time when the thing is to be delivered or the service is to be rendered was a controlling motive for the establishment of the contract. 4. When demand would be useless, as when the obligor has rendered it beyond his power to perform. With respect to the first two exceptions: • Mora Solvendi • • • Delay in the fulfillment of the obligation, by reason of a cause imputable to the debtor, or because of dolo (malice) or culpa (negligence). Must be either malicious or negligent, otherwise, the debtor cannot be held liable for damages. The delay may occur only in obligations which are positive (to give and to do), but not in obligations not to do, for in the latter the It is not enough that the law or the agreement of the parties fixes a date for performance; it must further state expressly that after the period lapses, default will commence. Example: a partner who has undertaken to contribute a sum of money and fails to do so. In such case, the law expressly says that the partner concerned thereby becomes a debtor of the partnership for the interest and damages from the time he should have complied with his obligation. With respect to the third exception: • It is essential that the time is the controlling motive for the establishment of the contract. Page | 19 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • In determining whether time is the essence in the contract, the ultimate criterion is the actual or apparent intention of the parties and before time may be so regarded by a court, there must be a sufficient manifestation, either in the contract itself or the surrounding circumstances of that intention. Example: time is the essence in exchange contracts because of the speculative and fluctuating value of the stocks. However, even where time is of the essence, a breach of the contract in the respect by one of the parties may be waived by the other party’s subsequent treating the contract as still in force. With respect to the fourth exception: • When the debtor has rendered the obligation beyond his power to perform demand is no longer necessary, as the same would only be useless formality. Example: a seller sold the same thing (a movable property) to two persons but he delivered the thing sild to the second buyer, who had no knowledge of the existence of the first sale. The seller shall incur in delay immediately after the lapse of the period agreed upon for the delivery of the thing sold to the first buyer as demand would already be useless considering that the seller has rendered the obligation beyond his power to perform. Rule on counting the prescriptive period: • • • The time for prescription for all kinds of actions, when there is no special provision which ordains otherwise, shall be counted from the day they may be brought. It is the legal possibility of bringing the action which determines the starting point for the computation of the prescriptive period for the action, and not necessarily the time of the making of an extrajudicial demand. Unless stipulated otherwise, an extrajudicial demand is not required before a judicial demand can be resorted to. Autocrop Group vs Intra Strata Assurance Corporation • A demand, whether judicial or extrajudicial, is not required before an obligation becomes due and demandable. It is only necessary in order to put an obligor in due and demandable obligation in delay, which in turn is for the purpose of making the obligor liable for interests or damages for the period of delay. Compensation Morae • The delay or default on the part of both parties neither has completed their part in their reciprocal obligations Effects of Mora Solvendi • • Reciprocal Obligations The debtor renders himself liable to the creditor for damages in case of default. The debtor remains liable for the loss of the thing due after he has incurred in delay even such loss was without his fault or by reason of a fortuitous evet. • • Basis: Articles 1165 and 1262 of the Civil Code. Solid Homes, Inc. vs Tan • The prescriptive period within which the oblige may bring an action against the obligor does not commence to run until a demand is made. • • Arising from the same cause, and wherein each party is a debtor and a creditor of the other, such that the obligation of one is dependent upon the obligation of the other. They are to be performed simultaneously, so that the performance of one is conditioned upon the simultaneous fulfillment of the other. Before a party can demand the performance of the obligation of the other, the former must also perform its own obligation. Delay by the other begins only from the moment one of the parties fulfills his obligation. Page | 20 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • Any claim of delay or non-performance against the other could prosper only if the complaining party had faithfully complied with its own correlative obligation. Requirement Obligation of Demand in Reciprocal General Rule: the fulfillment of the parties’ respective obligations should be simultaneous. • • The other party would incur in delay only from the moment the other party demand fulfillment of the former’s obligation. If the period of the fulfillment of the obligation is fixed, demand upon the oblige is still necessary before the obligor can be considered in default and before a cause of action for rescission will accrue. Mora Accipendi • Relates to the delay om the part of the oblige in accepting the performance of the obligation by the obligor. Requisites: 1. An offer of performance by the debtor who has the required capacity. 2. The offer must be to comply with the prestation as it should be performed. 3. The creditor refuses the performance without just cause. Article 1171. Responsibility arising from fraud is demandable in all obligations. Any waiver of an action for future fraud is void. (1102a) • The first kind of fraud merely gives to an action for damages while the second inf of fraud is a ground to seek the annulment of the contract. No waiver of Action for Future Fraud • The prohibition refers to waiver in advance, or prior to the commission of the fraud, or prior to the knowledge thereof. Reason: dictated by reason of public policy; otherwise, this kind of agreement would leave the obligation without efficacy. Exception: the prohibition does not extend to waiver of effects of fraud already committed and known to the parties. Article 1172. Responsibility arising from negligence in the performance of every kind of obligation is also demandable, but such liability may be regulated by the courts, according to the circumstances. (1103) Article 1173. The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. When negligence shows bad faith, the provisions of articles 1171 and 2201, paragraph 2, shall apply. If the law or contract does not state the diligence which is to be observed in the performance, that which is expected of a good father of a family shall be required. (1104a) Negligence (Culpa) Fraud (Dolo) Distinguished from fraud: One of the parties may resort to dolo or fraud only during the fulfillment of the obligation or for the purpose of inducing another to enter into a contract. • • In the first, the obligation already exists and fraud is committed only during its performance. In the second, it is fraud which gives rise to obligation. • • Fraud connotes some kind of dishonesty, malice or bad faith on the part of one of the parties. It is distinguished from negligence by the presence of deliberate intent, which is lacking in the latter. Culpa Aquilana vs Culpa Contractual Page | 21 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Culpa Aquilana Also known as culpa extra contractual, wrongful or negligent act or omission which creates vinculum juris and gives rise to an obligation between to persons not formally bound by any other obligation. Governed by Article 2176 an the immediately following articles. Has its source the negligence of the tortfeasor. The negligence or culpa is substantive and independent, which of itself constitutes the source of an obligation between persons not formerly connected by any legal tie. The negligence should be clearly established because it is the basis of the action. • occurring only during the performance of an already existing obligation. Culpa Contractual Refers to the fault or negligence incident in the performance of an obligation which is already existed, and which increases the liability from such already existing obligation. When negligence exists Governed by Articles 1170 – 1174. Basis: The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. Is premised upon the negligence in the performance of a contractual obligation. The negligence or culpa is considered as an accident in the performance of an obligation already existing – the vinculum exists independently of the breach of the voluntary duty assumed by the parties when entering into the contractual relation. The mere proof of the existence of the contract and the failure of its compliance justify, prima facie, a corresponding right of relief, without need of proving the negligence. • • • • There is no exact formula in determining the existence of negligence. As to whether the debtor is guilty of negligence, the same shall depend on the circumstances of each case. If the law or contract does not state the degree of diligence is to be observed in the performance of an obligation, then that which is expected of a good father of a family or ordinary diligence shall be required. The test to determine whether negligence attended the performance of an obligation is: Did the defendant in doing the alleged negligent act use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily prudent person would have used in the same situation? Negligence – the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or the doing or something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. When Culpa is Equivalent to Dolo • • While an action for future cannot be waived, the same rule cannot apply, with equal force, to an action for future negligence. The negligence connotes that absence of intent, therefore not serious as fraud, and the waiver of an action for future negligence is not contrary to public policy, such waiver is generally considered as valid. It is clear that the culpa or negligence referred to in Article 1170 is culpa contractual because the provision speaks of negligence Page | 22 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Waiver of an action for future negligence VALID Stipulation providing for absolute exemption from liability. VOID – because against public policy. Rule with respect to negligence showing bad faith: • • Definition of Fortuitous Event • • • Tantamount to fraud and shall therefore be governed by the provisions on fraud. Any waiver of an action for future negligence showing bad faith is also void. Are extraordinary events not foreseeable or avoidable, “events that could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable. Such event must be totally independent of the will of the debtor, or that it is produced by some other cause not imputable to him. If there is impossibility to foresee the event, it does not matter that it is avoidable. In the same way, if there is impossibility to avoid the event, it does not matter that it could have been foreseen. Caso Fortuito and Force Majure Contravention of Tenor of Obligation • • Every debtor who fails in performance of his obligation is bound to indemnify7 for the losses and damages caused thereby. It is not necessary that there should be either bad faith or negligence in order that there may be liability for damages. Article 1174. Except in cases expressly specified by the law, or when it is otherwise declared by stipulation, or when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk, no person shall be responsible for those events which could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable. (1105a) Caso Fortuito Force Majure Both terms refer to causes independent of the will of the obligor. Independent not Arises from an only of the will of the unavoidable debtor but also of happening, or from human will. an act, lawful or unlawful of a person other than the debtor, which act renders impossible of the debtor compliance with his obligation. Effects and Requisites of Fortuitous Event Fortuitous Event • • The impossibility of performing the obligation may provide the debtor with a legal excuse for his non-performance, if the same occurs without his fault and prior to him incurring delay. This impossibility may happen in two ways: either because the specific thing to be delivered in an obligation “to give” is lost or destroyed, or the prestation in an obligation “to do” becomes physically or legally impossible. • • No person shall be responsible for a fortuitous event. It excuses the debtor from liability for nonperformance of the obligation. Requisites: 1. The cause of the breach of the obligation must be independent of the will of the debtor. 2. The event must be either unforeseeable or unavoidable. 3. The event must be such as to render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill his obligation in a normal manner. Page | 23 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 4. The debtor must be free from any participation in, or aggravating of the injury to the creditor. Note: The burden of proving that the loss was due to a fortuitous event rests on him who invokes it, being a case of exemption from liability. • • In order for a fortuitous event to exempt one from liability, it is necessary that one has committed no negligence or misconduct that have occasioned the loss. The principle embodied in the act of God doctrine strictly requires that the act must be one accessioned exclusively by the violence of nature and all human agencies are to be excluded from creating or entering into the cause of the mischief. When the effect, the cause of which is to be considered, is found to be in part the result of the participation of man the whole occurrence is thereby humanized and removed from the rules applicable to the acts of God. Co vs CA • Robbery per se, just like carnapping, is not fortuitous event. It does not foreclose the possibility of negligence on the part of the debtor. Additional characteristic of fortuitous event: • Its occurrence must be such to render it impossible for a party to fulfill his obligation in a normal manner. Exceptions to Rule on Non-liability for fortuitous event Even when the requisites are present, the debtor shall remain liable even if the loss or damages is by reason of fortuitous event in the following instances: 1. When the law expressly provides for liability even for fortuitous event. 2. When the stipulation of the parties expressly provides for liability for fortuitous event. 3. When the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. Basis: Article 1262. An obligation which consists in the delivery of a determinate thing shall be extinguished if it should be lost or destroyed without the fault of the debtor, and before he has incurred in delay. When by law or stipulation, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous events, the loss of the thing does not extinguish the obligation, and he shall be responsible for damages. The same rule applies when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. (1182a) When Law Expressly Provides for Liability (See page 79 of Rabuya Book) Express Stipulation • • The law allows the parties to stipulate on a kind of diligence from that expected of a good father of a family, or the so-called “ordinary diligence.” In Art. 1174, the law expressly authorizes the parties to provide for liability even for fortuitous event. Assumption of Risks • Liability attaches even if loss was due to a fortuitous event if the nature of the obligation requires assumption. Example: The petitioner’s car was carnapped while it was in the possession of the private respondent for repair, the Court held the private respondent liable for the loss of the car due to carnapping. Article 1175. Usurious transactions shall be governed by special laws. (n) Usury Law in the Philippines Is the Usury Law still effective, or has it been repealed by Central Bank Circular No. 905, adopted Page | 24 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 on December 22, 1982, pursuant to its power under PD No.116, as amended by PD No. 1684? the creditor without reservation as to prior installments. Answer: Article 1176 in relation to Article 1253 Medel vs Court of Appeals • CB Circular No. 905 did not repeal nor in any way amend the Usury Law, but simply suspended the latter’s effectivity. First Metro Investment Corp. vs Estate Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc. • The illegality of usury is wholly the creature of legislation. A Central Bank Circular cannot repeal law. Only a law can repeal another law. Florendo vs CA • By virtue of the CB Circular 905, the Usury Law has been rendered ineffective. Article 1176 Relevant on questions pertaining to the effects and nature of obligations in general. Presumption does not resolve the question of whether the amount received by the creditor is a payment for the principal or interest. The amount received by the creditor is the payment for the principal. Note: • The imposition of an unconscionable rate of interest on a money debt, even if knowingly and voluntarily assumed, is immoral and unjust. Article 1176. The receipt of the principal by the creditor without reservation with respect to the interest, shall give rise to the presumption that said interest has been paid. The receipt of a later installment of a debt without reservation as to prior installments, shall likewise raise the presumption that such installments have been paid. (1110a) Two presumptions Established: 1. That interest has been paid if payment of the principal is received by the creditor without reservation with respect to the interest. 2. That prior installment has been paid if payment of a later installment is received by Resolves the doubt by presuming that the creditor waives the payment of interest because he accepts payment for the principal without any reservation. • Article 1253 Specifically pertinent on questions involving application of payments and extinguishment of obligations. The presumption resolves doubts involving payment of interest-bearing debts. The doubt pertains to the application of payment; the uncertainty is on whether the amount received by the creditor is payment for the principal or the interest. Resolves doubt by providing a hierarchy: payments shall first be applied to the interest; payment shall then be applied to the principal only after the interest has been fully-paid. The rule under Article 1253 that payments shall first be applied to the interest and not to the principal shall govern if two facts exists: (1) the debt produces interest, and (2) the principal remains unpaid. Page | 25 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1177. The creditors, after having pursued the property in possession of the debtor to satisfy their claims, may exercise all the rights and bring all the actions of the latter for the same purpose, save those which are inherent in his person; they may also impugn the acts which the debtor may have done to defraud them. (1111) General Remedies of Creditor to Protect and Satisfy His Credit Three Successive Measures The following successive measures must be taken by a creditor before he may bring an action for rescission of an allegedly fraudulent sale: Requisites: 1. That the creditor has a right of credit against the debtor although at the moment it is not liquidated. 2. The credit must be due and demandable. 3. Failure of the debtor to collect, that is, inaction of the debtor, whether the same be willful or negligent. 4. Insufficiency of the assets in the hands of the debtor although the creditor need not bring a separate action to show this exhaustion or insolvency of the debtor but he can prove the same in the very action to exercise the subrogatory action. Accion Pauliana 1. Exhaust the properties of the debtor through levying by attachment and execution upon all the property of the debtor, except such as are exempt by law from execution. 2. Exercise all the rights and actions of the debtor, save those personal to him (accion subrogatoria) 3. Seek rescission of the contracts executed by the debtor in fraud of their rights (accion pauliana) • • Without availing of the first and second remedies, the creditor cannot resort to the third measure. An action for rescission is a subsidiary remedy; it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. Accion Subrogatoria • • In situations where the creditor cannot in any way recover the credit because the debtor has no property or has property insufficient to satisfy his debts but he has credits or rights and bring all the actions of the debtor, except those which are inherent on his person. This action of the creditor is indirect because the creditor cannot in his own name file the action but in the name of the debtor. • • • The rescissory action to set aside contracts in fraud of creditors. Essentially a subsidiary remedy accorded under Article 1383 of the Civil Code which the party suffering damage can avail of only when he has no other means to obtain reparation for the same. The provision applies only when the creditor cannot recover in any other manner what is due him. Requisites: 1. That the plaintiff asking for rescission has a credit prior to the alienation, although demandable later. 2. That the debtor has made a subsequent contract conveying a patrimonial benefit to a third person. 3. That the creditor has no other legal remedy to satisfy his claim, but would benefit by rescission of the conveyance to the third person. 4. That the act being impugn is fraudulent. 5. That the third person who received the property conveyed, if by onerous title, has been an accomplice in the fraud. Page | 26 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 An accion pauliana presupposes the following: 1. A judgement 2. The issuance by the trial court of a writ of execution for the satisfaction of the judgement. 3. The failure of the sheriff to enforce and satisfy the judgment of the court. • • It requires that the creditor has exhausted the property of the debtor. The date of the decision of the trial court is immaterial. What is important is that the credit of the plaintiff antedates that of the fraudulent alienation by the debtor of his property. • • Essential Feature • • Article 1178. Subject to the laws, all rights acquired in virtue of an obligation are transmissible, if there has been no stipulation to the contrary. (1112) CHAPTER 3 Different Kinds of Obligations • • Article 1179. Every obligation whose performance does not depend upon a future or uncertain event, or upon a past event unknown to the parties, is demandable at once. • Pure Obligations • • • • Is one where the performance does not depend upon a condition. In order to become pure, it is sufficient that it contains no condition. It must not be subjected to a term or period. That in which no condition is placed, nor a day fixed for its compliance. Olivarez Realty Corporation vs Castillo Immediate demandability of an obligation does not imply a need for its immediate or instantaneous compliance. The court may still give the debtor a reasonable time within which to comply with the obligation and the same is not inconsistent with the idea of the obligation being immediately demandable nor alter its character as pure. Other obligations which are also immediately demandable SECTION 1 Pure and Conditional Obligations Every obligation which contains a resolutory condition shall also be demandable, without prejudice to the effects of the happening of the event. (1113) Pure obligation, or obligations whose performance do not depend upon a future or uncertain event, or upon a past event unknown to the parties, are demandable at once. Obligations with a resolutory period also take effect at once but terminate upon arrival of the day certain. Obligations which are subject to a resolutory condition or a resolutory term are also demandable at once. In resolutory condition, the existence or effectivity of the obligation is subject to extinguishment or termination upon the happening of an event or upon arrival of a day certain. In pure obligations, there is no event nor period that may affect the obligation’s existence or effectivity. Article 1180. When the debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit him to do so, the obligation shall be deemed to be one with a period, subject to the provisions of article 1197. (n) Article 1181. In conditional obligations, the acquisition of rights, as well as the extinguishment or loss of those already acquired, shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. (1114) Conditional Obligation Page | 27 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • The acquisition or rights, as well as the extinguishment or loss of those already acquired, shall depend upon the happening of the event that constitutes the condition. Any uncertain event which wields an influence on a legal relation. Every future and uncertain event upon which an obligation or provision is made to depend. • • • Condition • Potestative, Casual, and Mixed • Potestative – its fulfillment depends upon the exclusive will of either f the parties to the juridical relation. Casual – if its fulfillment depends upon chance or the will of either of the parties and partly upon chance or the will of a third person. Mixed – if its fulfillment is dependent partly upon the will of either of the parties and partly upon chance or the will of a third person. Condition vs Term Impossible and Possible Condition Uncertain to happen Term Certain to happen • • Example: • Death – it is a term – for while such event may be in future, its happening is something that is certain. As to whether a condition can be fulfilled or not. The impossibility in the latter case being either physical or legal. Positive or Negative • Depending upon whether the condition is an act or omission. Note: Divisible or indivisible • • for an event to be considered a condition, it is necessary that the happening of which must be something that is uncertain. The event must be a future one to satisfy the requirement of uncertainty – for the happening of an event that has already occurred in the past is no longer uncertain. When debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit to do so • • • • Conjunctive and Alternative • When the debtor binds himself to pay “when his means permit him to do so,” the obligation shall be considered to be one with a term. Classification of Conditions Whether by its nature, by agreement or under the law, the condition can be performed in parts. If it can be performed in parts – DIVISIBLE. If it cannot be performed in parts – INDIVISIBLE. • • According to as to whether, when there are several, all of them or only one must be performed. If all are required to be performed – CONJUNCTIVE. If only one is required to be performed – ALTERNATIVE. Suspensive and Resolutory Express and Implied Suspensive Resolutory Gives rise to an Results in the obligation. extinguishment of the obligations. • • According as to whether a condition is stated or merely inferred. If stated – EXPRESS Page | 28 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • If merely inferred – IMPLIED. Suspensive and Resolutory Conditions Suspensive Conditions Also called condition precedent or antecedent. If fulfilled, the obligation arises. Resolutory Conditions Also called condition subsequent. If fulfilled, the obligation extinguishes. If not fulfilled, the If not fulfilled, the legal tie does not legal relation is make its consolidated. appearance. While the doubt Its effects flow, but lasts, the obligation over it hovers a does not appear, threat of extinction. but its existence is a hope. which is not performed, such party may refuse to proceed with the contract or he may waive performance of the condition x x x. Gonzales vs Lim If the condition was imposed on an obligation of a party which was not complied with, the other party may either: 1. Refuse to proceed with the agreement. 2. Waive the fulfillment of the condition. Obligations Subject to a resolutory Condition Resolutory Condition • • Obligations Subject to a Suspensive Condition • • • The acquisition or rights (and correspondingly the existence of the debts) shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. The birth or effectivity of the obligation only takes place if and when the event constituting the condition happens or fulfilled, and if the suspensive condition does not take place, the parties would stand as of the conditional obligation had never existed. Condition imposed on the perfection of a contract • The failure of such condition would prevent the juridical relation itself from coming into existence. Condition imposed merely on the performance of an obligation • The other party may either refuse to proceed or waive said condition. Basis: Article 1545. Where the obligation of either party to a contract of sale is subject to any condition Extinguishes the obligation upon its fulfillment. Where the extinguishment or loss of rights already acquired shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. An obligation subject to a resolutory condition is immediately demandable but it is extinguished upon the happening of the condition. During Pendency • • The obligation is immediately demandable as if it were a pure obligation. But once the resolutory condition is fulfilled, the obligation is extinguished and the parties are required to return to each other what they have received. The same condition which is resolutory on the part of the creditor is also deemed suspensive on the part of the debtor because that latter has an expectancy or hope that what he had delivered will be returned to him upon the fulfillment of the resolutory condition. Article 1182. When the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor, the conditional obligation shall be void. If it depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person, the obligation shall take effect in Page | 29 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 conformity with the provisions of this Code. (1115) Mixed • Article 1183. Impossible conditions, those contrary to good customs or public policy and those prohibited by law shall annul the obligation which depends upon them. If the obligation is divisible, that part thereof which is not affected by the impossible or unlawful condition shall be valid. When the fulfillment of a condition is dependent partly on the will of one of the contracting parties, or of the obligor, and partly on chance, hazard or the will of a third person. Effect Upon Obligation Potestative Condition The condition not to do an impossible thing shall be considered as not having been agreed upon. (1116a) Article 1184. The condition that some event happen at a determinate time shall extinguish the obligation as soon as the time expires or if it has become indubitable that the event will not take place. (1117) Article 1185. The condition that some event will not happen at a determinate time shall render the obligation effective from the moment the time indicated has elapsed, or if it has become evident that the event cannot occur. • • • • If no time has been fixed, the condition shall be deemed fulfilled at such time as may have probably been contemplated, bearing in mind the nature of the obligation. (1118) • Article 1186. The condition shall be deemed fulfilled when the obligor voluntarily prevents its fulfillment. (1119) Article 1182 declares void a conditional obligation when the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor. A condition a once facultative and resolutory may be valid though the condition is made to depend upon the will of the debtor. The obligation is void when the condition is potestative to the debtor and, at the same time suspensive, because to allow such conditions would be sanctioning illusory obligations. If the condition is at the same time resolutory, although dependent upon the debtor’s will, the obligation is not illusory because the debtor is naturally interested in the fulfillment of the resolutory condition in order to reacquire rights which have already been vested in the creditor. The rule that the conditional obligation itself is void applies only to obligation which depends for its perfection upon a condition which is potestative to the debtor and not to a pre-existing obligation. Potestative, Casual and Mixed Conditions Osmena vs Rama Potestative • • • also referred to as facultative. When its fulfillment depends exclusive upon the will of one of the contracting parties. Where the so-called potestative condition is imposed not on the birth of the obligation but on its fulfillment, only the condition is avoided, leaving unaffected the obligation itself. Casual • Is one the fulfillment of which depends upon chance, hazard, or the will of a third person. “She imposed the condition that she would pay the obligation if she sold her house.” • If that statement acknowledgement of found in her the indebtedness Page | 30 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • should be regarded as a condition, it was a condition which depended upon her exclusive will, and is therefore, void. Only the condition is avoided because the potestative condition was imposed only on the fulfillment of a pre-existing obligation. Trillana vs Quezon College • The potestative condition was imposed on the birth of the obligation and not on its fulfillment. “She will pay the full value of subscription after she had harvested fish.” Damasa died without paying for subscription. • • • Osemna Case The condition referred merely to the fulfillment of an already existing indebtedness. Article 1182 is silent on the effect of a condition that is solely dependent on the will of the creditor. The obligation does not become illusory even if the same is conditional and the fulfillment of the condition is dependent on the sole will of the creditor because in the very nature of things the creditor is naturally interested in the fulfillment of the condition as the same will give rise to the acquisition of rights in his favor. “Their payment should be made by Fernando Hermosa, Sr. as soon as he receives funds derived from the sale of his property in Spain.” • Mixed Conditions fulfillment of In such cases of mixed conditions, what will happen if the part that depends on chance or on the will of a third person was already fulfilled but the debtor intentionally prevents the fulfillment of the part that depends on him? • The doctrine of constructive fulfillment of suspensive condition will apply. Requisites: 1. The condition is suspensive. 2. The obligor actually prevents the fulfillment of the condition. 3. He acts voluntarily. • When the condition is casual, or when the fulfillment of the condition depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person, the obligation is valid and shall take effect in conformity with the provisions of the Civil Code. The obligation was valid because the condition of the obligation was not a purely potestative one, depending exclusively upon the will of the debtor, but a mixed one, depending partly upon the will of the debtor and partly upon chance. Doctrine of Constructive suspensive condition Casual Conditions • The law is silent as to the effects of mixed conditions upon the obligation. The law appears to sanction the validity of an obligation subject to a mixed condition although the fulfillment of which depends partly upon the will of the debtor. Hemosa vs Longara The obligation was void pursuant to Article 1182 because the condition is dependent upon the debtor’s sole will. Trillana Case The condition would have served to create the obligation to pay. • • • • There must be intent on the part of the obligor to prevent the fulfillment of the condition and there must be actual prevention of the fulfillment. Mere intention of the debtor to prevent the happening of the condition, or to place ineffective obstacles to its compliance, without actually preventing the fulfillment, is sufficient. If the requisites are present, Article 1186 declares that the part of the condition which Page | 31 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 depends on the debtor shall be deemed fulfilled. International Hotel Corporation vs Joaquin • Thee doctrine of constructive fulfillment of a suspensive condition was not applicable because of the absence of intent on the part of the obligor to prevent the fulfillment of the condition. • Impossible Conditions • Note: the doctrine of constructive fulfillment of suspensive condition applies only to cases of mixed conditions where a part of the condition depends on the will of the debtor and finds no application to potestative conditions that depend exclusively on the debtor because in the latter case the conditional obligation itself is void. also upon the will of third persons who could in no way be compelled to fulfill the condition. Under the doctrine of constructive fulfillment of a suspensive condition, it is the debtor himself who intentionally prevents the fulfillment of the condition. • • Conditions are considered physically impossible when they are incompatible with or contrary to nature. Conditions are deemed juridically impossible if they are contrary to good customs, public policy or those prohibited by law. A condition is possible if it is valid and allowed by law. Effects of Impossible Condition Rule on Constructive fulfillment of Mixed Conditional Obligation On obligations • In mixed conditions that depend partly on the will of the debtor and partly upon the will of the third person, what will happen to the obligation if the debtor has done all in his power to comply with the obligation but the condition has nit been fulfilled because its fulfillment likewise depend upon the will of third persons who could in no way be compelled to fulfill the condition? • When the condition was not fulfilled but the obligor did all his power to comply with the obligation, the condition should be deemed satisfied. Stated otherwise, the debtor will be deemed to have sufficiently performed his part of the obligation, if he has done all that was in his power, even if the condition has not been fulfilled in reality. Note: • Under the rule on constructive fulfillment of a mixed conditional obligation, the obligor did all in his power to comply with the obligation and the condition is not fully complied because its fulfillment depended not only upon the effort of the obligor but Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 The obligation is void if it depends upon an impossible condition. Exception: if the obligation is divisible, the part thereof which is not affected by the impossible or unlawful condition shall be valid. • A condition not to do an impossible thing shall be considered as not having been agreed upon, in which case, the obligation is to be regarded as pure as if there were no condition. On Simple and Remuneratory Donations Pure and simple donations – is one where the underlying cause is plain gratuity. Remuneratory or Compensatory Donation – is one made for the purpose of rewarding the donee for past services, which services do not amount to a demandable debt. • Under Article 727, illegal or impossible conditions in simple and remuneratory donations shall be considered as not imposed. Page | 32 • • • • The simple or remuneratory donation remains valid even if it depends upon an impossible condition. With respect to onerous donations, or those which imposes upon the done a reciprocal obligation or those made for valuable consideration, the cost of which is equal to or more than the thing donated. Under Article 733, donations with an onerous cause shall be governed by the rules on contracts. An onerous donation is void if it depends upon an impossible condition, applying the rule in Article 1183. • Example: I will give B a car if he becomes a lawyer before he turns 25. • On testamentary dispositions • • • A testamentary disposition in a last will and testament remains valid if the same depends upon an impossible condition. Article 873 provides that impossible conditions and those contrary to law or good customs shall be considered as not imposed and shall in no manner prejudice the heir, even if the testator should otherwise provide. Those impossible conditions imposed on will are simply disregarded and do not, as a consequence, affect the validity of testamentary dispositions. • • • Positive and Negative Conditions Positive Conditions • • Article 1184 Those which require the happening of an event. Negative Conditions • • Article 1185 Those which require the non-happening of an event. If the condition is both positive and suspensive, the non-happening of the event which constitutes as the condition shall The obligation is certain not to exist from the moment B reaches the age of 25 and has not graduated from the law school, although he may eventually pass the bar examinations and become lawyer afterwards. The obligation is certain not to exist if B is still in his second year in the College of Law when he turns 24, for in the latter situation, it is definite that the event will not take place. If the condition is both positive and resolutory, the non-happening of the event which constitutes as the condition shall result in the consolidation of rights that have already been acquired by the creditor. If the resolutory condition is required to happen at a determinate time, the right of the creditor becomes absolute “as soon as the time expires or if it has become indubitable that the event will not take place.” Example: I am giving B my collection of law books but if my son, C, becomes a lawyer when he turns 25, those law books will have to be given back to C. • Effects of Positive Conditions • prevent the obligation from coming into existence. If the suspensive condition is required to happen at a determinate time, the obligation is sure not to exist “as soon as the time expires or if it has become indubitable that the event will not take place. • The right of B over said law books will become absolute from the moment C reaches the age of 25 and has not graduated from the law school, although he may eventually pass the bar examinations and become a layer afterwards. The obligation shall also become effective if B marries another when she turns 24, for in Page | 33 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 the latter situation, it is evident that the event which serves as the condition can no longer occur. (3) When the thing deteriorates without the fault of the debtor, the impairment is to be borne by the creditor; Article 1187. The effects of a conditional obligation to give, once the condition has been fulfilled, shall retroact to the day of the constitution of the obligation. Nevertheless, when the obligation imposes reciprocal prestations upon the parties, the fruits and interests during the pendency of the condition shall be deemed to have been mutually compensated. If the obligation is unilateral, the debtor shall appropriate the fruits and interests received, unless from the nature and circumstances of the obligation it should be inferred that the intention of the person constituting the same was different. (4) If it deteriorates through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may choose between the rescission of the obligation and its fulfillment, with indemnity for damages in either case; In obligations to do and not to do, the courts shall determine, in each case, the retroactive effect of the condition that has been complied with. (1120) Article 1188. The creditor may, before the fulfillment of the condition, bring the appropriate actions for the preservation of his right. The debtor may recover what during the same time he has paid by mistake in case of a suspensive condition. (1121a) Article 1189. When the conditions have been imposed with the intention of suspending the efficacy of an obligation to give, the following rules shall be observed in case of the improvement, loss or deterioration of the thing during the pendency of the condition: (5) If the thing is improved by its nature, or by time, the improvement shall inure to the benefit of the creditor; (6) If it is improved at the expense of the debtor, he shall have no other right than that granted to the usufructuary. (1122) Article 1190. When the conditions have for their purpose the extinguishment of an obligation to give, the parties, upon the fulfillment of said conditions, shall return to each other what they have received. In case of the loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing, the provisions which, with respect to the debtor, are laid down in the preceding article shall be applied to the party who is bound to return. As for the obligations to do and not to do, the provisions of the second paragraph of article 1187 shall be observed as regards the effect of the extinguishment of the obligation. (1123) Effects of Suspensive Condition Prior fulfillment of Suspensive Condition (1) If the thing is lost without the fault of the debtor, the obligation shall be extinguished; • (2) If the thing is lost through the fault of the debtor, he shall be obliged to pay damages; it is understood that the thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered; • • The right is yet to be acquired and the debt is yet to exist – the parties are not yet actual debtor and creditor of each other, as the legal tie does not make its appearance yet. When the obligation assumed by a party to a contract is expressly subjected to a suspensive condition, the obligation cannot be enforced against him unless the condition is complied with. If the debtor has paid by reason of mistake prior to the fulfillment of the condition, he has Page | 34 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 the right to recover the undue payment based on the principle of solution indebiti. Reciprocal Obligations • Reason: the payment is not due since the obligation has not come into existence yet. • • • It is necessary that the recovery of what had been paid by mistake should be done prior to the fulfillment of the suspensive condition. Once the suspensive condition is fulfilled, the effects of such conditional obligation shall retroact to the day of its constitution, thus, effectively barring any action for recovery based on solution idebiti. The payor must not have been aware that the condition has not yet been fulfilled. Purpose: The obvious purpose of such modification is to avoid the necessity of mutual accounting for the fruits and interests received. Unilateral Obligations • But what if the payor is aware that the condition is not yet fulfilled but he makes the payment voluntarily? Can he still recover the payment? • • If the intention is to do away with the condition and to convert the obligation into a pure one, it is obvious that the payment already becomes due and may no longer be recovered. If the intention is simply to make the delivery even prior to the fulfillment of the condition but upon the expectation that the condition would happen, it is only logical and just that the debtor be allowed to recover what he has paid if it will become clear that the event will not anymore take place. Retroactive Effect of fulfillment of suspensive condition The second paragraph of Article 1187 modifies the application of the rule of retroactivity by providing for the mutual compensation of the fruits and interest that may have accrued during the pendency of the condition. It is the debtor who shall be entitled to the fruits and interests received up to the day the condition is fulfilled, unless from the nature and circumstances of the obligation it should be inferred that the intention of the person constituting the same was different. In obligation to do or not to do • • The does not provide for a specific formula in determining the effects of the fulfillment of the suspensive condition. The second paragraph of Article 1187 entrusts to the sound discretion of the court the determination of such effects in each case. Effects of Loss of Specific Thing Due During Pendency of Condition (1) If the thing is lost without the fault of the debtor, the obligation shall be extinguished; Obligation to Give • • Once the condition is fulfilled, the effects of a conditional obligation to give retroact to the day on which the obligation was constituted, as if it were a pure obligation from the first day. The rule of retroactivity of the effects of conditional obligation to give, once the condition has been fulfilled, is without prejudice to the existence of a preferred right of a third person who may have dealt with the same property in good faith. (2) If the thing is lost through the fault of the debtor, he shall be obliged to pay damages; it is understood that the thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered; (3) When the thing deteriorates without the fault of the debtor, the impairment is to be borne by the creditor; Page | 35 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 (4) If it deteriorates through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may choose between the rescission of the obligation and its fulfillment, with indemnity for damages in either case; (5) If the thing is improved by its nature, or by time, the improvement shall inure to the benefit of the creditor; (6) If it is improved at the expense of the debtor, he shall have no other right than that granted to the usufructuary. • • • These rules are necessary in view of the retroactive effects of the happening of the suspensive condition. These rules will only apply in the event that the condition is fulfilled. These rules apply only to specific or determinative obligation. Effect of loss during pendency of condition • If the obligation is generic in the sense that the object thereof is designated merely by its class or genus without any particular designation or physical segregation from all others of the same class, the loss or destruction of anything of the same kind in the debtor’s possession will not have the effect of extinguishing the obligation, even if such loss or destruction is without the debtor’s fault an before he has incurred in delay. Basis: The genus of a thing can never perish. Genus nunquan perit. • • If the thing is lost through the fault of the debtor, the obligation to give a determinate thing is not extinguished Once the suspensive condition is fulfilled, the effects thereof shall still retroact to the day of the constitution of the obligation but the obligation of the debtor is converted into payment of damages to the creditor. The determinate thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered. Perishes – when it dies, in the case of animate objects; when it rots in the case of perishable goods. Goes out of commerce – when its possession has become unlawful, as where it has been used as an instrument in the commission of a crime, or it can no longer be the object of contracts, as where the land which is the subject-matter of the obligation to give has been expropriated for public use. Disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown – when for example in the case of wild animal, it has escaped and regained its freedom and cannot be found. Cannot be recovered – when for instance in the case of a ship, it sunk in the middle of the sea. • If during the pendency of the condition the thing is lost without the lost of the debtor, such as when the thing is lost by reason of fortuitous event, the obligation is extinguished even if later on the suspensive condition is fulfilled. Even if the thing is lost by reason of fortuitous event, the loss of the thing does not extinguish the debtor’s obligation in the following situations: 1. When by law, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous event. 2. When by stipulations, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous event. 3. When the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risks. Effects of deterioration of specific thing due during pendency of condition If the thing deteriorates during the pendency of the suspensive condition and the condition is later on fulfilled, the following rules shall apply: 1. If the deterioration occurs without the fault of the debtor, the same is to be suffered by the creditor who bears the risks. Page | 36 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 2. If the deterioration is through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may choose between: a. The rescission of the obligation, with indemnity for damages. b. The fulfillment of the obligation, with indemnity for damages. Effects of improvement of specific thing due during pendency of condition • • If the thing improves by nature without the intervention of the debtor, such improvement inures to the benefit of the creditor because he also suffers the deterioration of the thing without the fault of the debtor. If the thing is improved at the debtor’s expense, he is only granted the rights of a usufructuary in relation to such improvements upon the condition. • • Not entitled to the reimbursement of the expenses he incurred in connection with the improvements that he may have introduced on the property. He is granted a right to remove the improvements of the removal will not cause injury to the property. He may set off his liability for damages caused to the property with the value of the said improvement. Effects of Resolutory Condition During Pendency of Condition • • • An obligation with a resolutory condition is immediately demandable but without prejudice to the effects of the happening of the condition. During the pendency of the condition, the obligation is immediately demandable as if it were a pure obligation. The same condition which is resolutory on the part of the creditor is also deemed suspensive on the part of the debtor because the latter has an expectancy or hope that what he had delivered will be returned to him of the resolutory Effects of fulfillment of resolutory condition • • • Usufructuary • fulfillment • • If the resolutory conditions fulfilled, the obligatory relation in its entirety is extinguished. Both the rights of the creditor and the duties of the debtor are extinguished; so that if the resolutory condition does takes place, the parties would stand as if the conditional obligation had never existed. Since the obligatory relation is extinguished in its entirety, all the effects that were produced by the obligation would have to be erased since the parties would have to go back to their status prior to the constitution of the obligation – and this is accomplished by returning to each other whatever they may have received by reason of the obligation, including fruits and interests. In obligation to do or not to do, the effects of the fulfillment of the resolutory condition shall be determined by the court in case, following the provisions of paragraph 3 of Article 1190, in relation to paragraph 2 or Article 1187. In case of loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing to be returned during the pendency of the resolutory condition. Article 1191. The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent upon him. The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission of the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should become impossible. The court shall decree the rescission claimed, unless there be just cause authorizing the fixing of a period. This is understood to be without prejudice to the rights of third persons who have acquired the Page | 37 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 thing, in accordance with articles 1385 and 1388 and the Mortgage Law. (1124) Article 1192. In case both parties have committed a breach of the obligation, the liability of the first infractor shall be equitably tempered by the courts. If it cannot be determined which of the parties first violated the contract, the same shall be deemed extinguished, and each shall bear his own damages. (n) • • • Tacit Resolutory condition in reciprocal obligations Reciprocal obligations are those arises from the same cause and in which each party is a debtor and a creditor of the other at the same time, such that the obligations of one are dependent upon the obligations of the other. They are to be performed simultaneously, so that the performance of one is conditioned upon the simultaneous fulfillment by the other. For one party to demand the performance of the obligation of the other party, the former must also perform its own obligation. Implied right to rescind (or resolution) • • • The condition is imposed by law and applies even if there is no corresponding agreement thereon between the parties. Reciprocal obligations a party incurs in delay once the other party has performed or is ready and willing to perform may rescind the obligation if the other does not perform, or is not ready and willing to perform. The remedy of resolution applies only to reciprocal obligations such that a party’s breach thereof partakes of a tacit resolutory condition which entitles the injured party to rescission. Example: A contract of sale creates reciprocal obligations. The seller obligates itself to transfer the ownership of and deliver a determinate thing, and the buyer obligates itself to pay therefor a price certain in money or its equivalent. Remedies in Case of Breach of Reciprocal Obligations Specific Performance • Applies only to reciprocal obligations Reciprocal Mutual Prestations obligations There must be They are mutually reciprocity between obligated, but the them obligations are not reciprocal. Both relations must arise from the same cause, such that one obligation is correlative to the other. A person may be the debtor of another by reason of an agency, and his creditor by reason of a loan. • The remedy of requiring exact performance of a contract in the specific form in which it was made, or according to the precise terms agreed upon. It pertains to the actual accomplishment of a contract by a party bound to fulfill it. Resolution • • The unmaking of a contract for a legally sufficient reason. It does not merely terminate the contract and release the parties from further obligations to each other, but abrogates the contract from its inception and restores the parties to their original positions as if no contract gas been made. Mutual Restitution • Entails the return of the benefits that each party may have received as a result of the contract, is thus required. Page | 38 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • The right of rescission of a party to an obligation is predicated on a breach of faith by the other party ho violates the reciprocity between them, and not some injury to economic interests on the part of the party plaintiff. providing that a violation of the terms of the contract would cause its cancellation even without judicial intervention. Calilap – Asmeron vs Development Bank of the Philippines • Is it absolute? • • The right to rescind under Article 1191 is not absolute. For a contracting party to be entitled to rescission (resolution), the other contracting party must be in substantial breach of the terms and conditions of their contract. Reason: rescission will not be permitted for a slight or casual breach of the contract, but only for such breaches that are substantial and fundamental as to defeat the object of the parties in making the agreement. Right to Rescind Must Be Invoked Judicially • • • The party entitled to rescind should apply to the court for a decree of rescission. The right cannot be exercised solely on a party’s own judgement that the other committed a breach of the obligation. The operative act which produces the resolution of the contract is the decree of the court. Where both parties committed infractions • • • • The general rule is that in the absence of a stipulation, a party cannot unilaterally and extrajudicially rescind a contract. Where there is nothing in the contract empowering the injured party to rescind it without resort to the courts, the injured party’s action in unilaterally terminating the contract is unjustified. Exception: A judicial action for the rescission of a contract is nit necessary where the contract provides that it may be revoked and cancelled for violation of any of its terms and conditions. The rationale for the foregoing is that in contracts providing for automatic revocation, judicial intervention is necessary not for purposes of obtaining a judicial declaration rescinding a contract already deemed rescinded by virtue of an agreement providing for rescission even without judicial intervention, but in order to determine whether or not the rescission was proper. • None of them can seek judicial redress for the cancellation or resolution of their contract and they are therefore bound to their respective obligations thereunder. As to their liability for damages to each other, that will depend on whether it can be determined which of them first violated the contract. If it cannot be determined which of the parties first violated the contract, the parties’ respective claims for damages are deemed extinguished and each of them shall bear its own damage. The second infractor is not liable for damages at all because the damages for the second breach are compensated instead by mitigation of the first infractor’s liability for damages arising form his earlier breach. Article 1192 does not really exculpate the second infractor from liability because the second infractor is actually punished for his breach by mitigating the damages to be awarded to him from the previous breach of the other party. Reason: The law on obligations and contracts does not prohibit parties from entering into agreement Page | 39 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 SECTION 2 Obligations with a Period Article 1193. Obligations for whose fulfillment a day certain has been fixed, shall be demandable only when that day comes. Obligations with a resolutory period take effect at once, but terminate upon arrival of the day certain. A day certain is understood to be that which must necessarily come, although it may not be known when. If the uncertainty consists in whether the day will come or not, the obligation is conditional, and it shall be regulated by the rules of the preceding Section. (1125a) Article 1194. In case of loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing before the arrival of the day certain, the rules in article 1189 shall be observed. (n) It may only suspend the demandability of the obligation, but without affecting its existence, or cause its termination, but without annulling its existence. “if the uncertainty consists in whether the day will come or not.” The period must end on a day certain. “That which must necessarily come, although it may not be known when.” It may cause the obligation to exist or to cease to exist. Classification of Term Suspensive period (ex die) • Is one that must necessarily come before the performance of the obligation can be demanded. Resolutory period (in diem) Article 1195. Anything paid or delivered before the arrival of the period, the obligor being unaware of the period or believing that the obligation has become due and demandable, may be recovered, with the fruits and interests. (1126a) Obligations with a term or period • Is that whose consequences or effects are subjected in one way or another to the expiration of said term or period. Term or Period • • The period which results in the termination of the obligation upon its arrival. Definite – if the date is fixed or when the date of the happening of the event is known. Indefinite – if the event is sure to happen but the exact timing of its happening is not known. Legal – fixed by law. Conventional – fixed by the party. Judicial – fixed by the courts. A space of time which, exerting an influence in an obligation as a result of a juridical act, either suspends its demandability or produces its extinguishment. Condition Term The happening of The even is certain the event is to happen. something that is uncertain. Effects of Suspensive and Resolutory Periods Suspensive Term or Period • If the term or period is suspensive, the obligation becomes demandable only when the day certain arrives. Page | 40 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • • • The term or period does not affect the existence of the obligation not its effectivity. What is suspended by the term is only the demandabilty of the obligation. The obligation already exists but it cannot as yet be enforced against the debtor because the obligation is not yet demandable. The right of action only arises when the date fixed has arrived and the obligation is enforceable only when the day comes. The period of prescription is to be counted on that day and not from the date of the obligation. If delivery or payment has been made prior to the arrival of the day certain, Article 1195 authorizes the debtor to recover what has been delivered prematurely, together with fruits and interest, but only if the debtor made the delivery or payment “being unaware of the period or believing that the obligation has become due and demandable. (See rules ss to the extent of what may be recovered on pages 133 – 134.) • Should the debtor effected the premature delivery with knowledge of the period or with knowledge that the obligation was not yet due and demandable at that time, there can be no recovery of what has been paid or delivered in because the debtor is deemed to have waived the benefit of the term or period, thus making the obligation immediately demandable. Resolutory Term or Period • Obligations with a resolutory period take effect at once, but terminate upon arrival of the day certain. The effects of the arrival of the day certain in obligations with a resolutory term. Effects of the fulfillment of a resolutory condition in conditional obligations The termination of The obligation is the obligation extinguished upon contemplated in the fulfillment of the Article 1193 does condition and the not annul the fact of parties will be its existence. restored to their status prior to the constitution of the obligation, such that they will be required to return to each other what they have received. A period does not carry with it, except when there is a special agreement, the same accompaniment of retroactive effects that follow a condition. Effects of Loss, Deterioration or Improvement Prior to Arrival of Day Certain • Pursuant to Article 1194, the same rule established in Article 1189 relating to the loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing due during the pendency of a suspensive condition are also applicable in case of loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing due prior to the arrival of the day certain in obligations with a suspensive term. Article 1196. Whenever in an obligation a period is designated, it is presumed to have been established for the benefit of both the creditor and the debtor, unless from the tenor of the same or other circumstances it should appear that the period has been established in favor of one or of the other. (1127) Article 1197. If the obligation does not fix a period, but from its nature and the circumstances it can be inferred that a period was intended, the courts may fix the duration thereof. The courts shall also fix the duration of the period when it depends upon the will of the debtor. Page | 41 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 In every case, the courts shall determine such period as may under the circumstances have been probably contemplated by the parties. Once fixed by the courts, the period cannot be changed by them. (1128a) Article 1198. The debtor shall lose every right to make use of the period: (1) When after the obligation has been contracted, he becomes insolvent, unless he gives a guaranty or security for the debt; (2) When he does not furnish to the creditor the guaranties or securities which he has promised; cannot make and effective tender and consignation of the payment. • • Tenor of Obligation or Other Circumstances • • (3) When by his own acts he has impaired said guaranties or securities after their establishment, and when through a fortuitous event they disappear, unless he immediately gives new ones equally satisfactory; (4) When the debtor violates any undertaking, in consideration of which the creditor agreed to the period; • • • (5) When the debtor attempts to abscond. (1129a) Benefit of Period Disputable Presumption • • In case it does not appear, either from any circumstances, or from the tenor of the contract, that the designated period has been established for the benefit of one of the parties only, it is presumed to have been established for the benefit of both the creditor and the debtor. This presumption applies only when the parties to a contract themselves have fixed the period. If the period is for the benefit of the debtor only, he may validly pay at any time before the period expires but he may oppose a premature demand for payment. If the period is for the benefit of the creditor only, he may demand performance at any time but the debtor cannot compel him to accept payment before the period expires. The tenor of the obligation may already indicate for whose benefit the period has been established. If the obligation expressly provides that the period is for the benefit of both parties, then there is no need to apply the presumption established in Article 1196. The tenor of the obligation may also indicate that the period is for the benefit of the debtor. The inquiry need not be limited to the tenor of the obligation. The required proof need not be supplied by the contract itself as evidence aliunde may be taken into account. In contracts of loan, the circumstance that the loan bears an interest is indicative of the fact that the period is for the benefit of both parties: the term benefits the debtor by the use of the money, as well as the creditor by the interest. Instances that the loan is in favor of both parties: • • • The desire of the creditor to protect himself against the sudden decline in the purchasing power of the currency due to its fluctuating nature. If the creditor receives other benefits by reason of the term in lieu of the interest. Payment cannot be made by the debtor before the stipulated term without the consent of the creditor. When debtor loses benefit of period Reason: The legal import of the presumption is that, prior to the arrival of the stipulated period, the creditor cannot demand payment, and the debtor • When any of these instances takes place, the obligation is converted into a pure obligation Page | 42 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 and, therefore, becomes immediately due and demandable, even if the period has not expired. Insolvency • • • When Court is Authorized to Fix Period Instances when Courts are authorized to fix period It is sufficient that the debtor is in a state of financial difficulty or that he is unable to pay his debts in the ordinary course of business. The debtor may still retain the right to such period even after he becomes insolvent, provided he gives guaranty or security for the debt. Failure to furnish security • (5) When the debtor attempts to abscond. The debtor to have lost the benefit of the period by reason of her failure to give and register the security agreed upon in the form of the two deeds of mortgage. But the debtor may preserve the benefit of the period by constituting the securities or guaranties he has failed to give, even when the article makes no reservation to this effect. 1. When the obligation does not fix a period, but from its nature and the circumstances it can be inferred that a period was intended. 2. When the duration of the period when it depends upon the will of the debtor. 3. In case of breach of reciprocal obligation, the court may refuse to order rescission if there is a just cause for the fixing of a period. 4. In lease of urban lands, the court may fix a longer period in case daily, weekly or monthly is paid and the lessee has occupied the premises for more than one month, or more than six months, or more than one year, respectively. When a period is intended but no period was fixed Impairment or Loss of Security Example: Effects of the debtor’s own act Mere impairment of the guaranties or securities is sufficient in order for the debtor to lose every right to make use of the period. In an obligation to construct a house, the general rule provided in Article 1197 of the Civil Code applies, which provides that the courts may fix the duration thereof because the fulfillment of the obligation itself cannot be demanded until after the court has fixed the period for compliance therewith and such period has arrived. Fortuitous Event The law requires total disappearance of the guaranties or securities before the debtor can lose such right. The debtor may preserve the benefit of the period if he immediately gives new but equally satisfactory guaranties or securities. Other Grounds: (4) When the debtor violates any undertaking, in consideration of which the creditor agreed to the period; Courts are not authorized to fix duration of the period in the following instances: 1. When no period was intended by the parties. 2. When the obligation is payable on demand because it is a pure obligation and not one with a period. 3. When the performance of the obligation was fixed within a reasonable time because a period was already fixed, a reasonable time; and that the court should do is to determine if that reasonable time had already elapsed or not when suit was filed. 4. When the law itself provides for the period. Page | 43 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 When Duration Debtor’s Will • • • • • of Period Depends Upon Article 1182 declares the conditional obligation void when the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor. When what is left to the will of the debtor is only the duration of the period, the second paragraph of Article 1197 considers the obligation as valid and said provision authorizes the courts to fix the period in such a situation. When the debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit him to do so, the obligation shall be deemed to be one with a period, subject to the provisions of article 1197, and not a conditional obligation. What is left to the will of the debtor is not the existence or validity of the obligation but merely the duration of the term for its fulfillment. The courts are also authorized to fix the period because the duration thereof depends upon the will of the debtor: o When the term of the lease has been upon the will of the debtor. o When the debtor promises to pay his indebtedness consisting of the sum of money “little by little.” Or “in partial payments,” or “as soon as possible,” or “as soon as I have money.” Action to Fix Period • • • • The only action which the obligor must comply with his obligation for the reason that the fulfillment of the obligation itself cannot be demanded until after the court has fixed the period for its compliance and such period has arrived. Plaintiff may not ask for the performance of the obligation without first asking for the fixing by the court of the period or term. The period should first be determined, because in the absence of such term or period, there can be no breach of contract or failure to perform the obligation. Where a prior and separate action fix a period would be more formality and serve no other purpose but delay, there is no necessity for such prior action. The action which should be brought in accordance with Article 1197 The right to have the period judicially fixed is born from the date of the agreement itself which contains the undetermined period. The action to enforce the obligation In which case the action to enforce the same prescribes within a period of 10 years from the time the right of action accrues, the action to have the court fix the period also prescribes within the same period. Extrajudicial demand is not essential for the creation of this cause of action to have the period fixed. It exists by operation of law from the moment such an agreement subject to an undetermined period is entered into, whether the period depends upon the will of the debtor alone, or of the parties themselves, or where from the nature and the circumstances of the obligation it can be inferred that a period was intended. Period fixed by Court is Final Page | 44 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • When the authority granted by Article 1197 is exercised by the courts, the same do not amend or modify the obligation concerned. Whenever a period is fixed, the court merely enforces or carries out an implied stipulation in the contract in question. In fixing said period, the Court merely ascertains the will of the parties and gives effect thereto. From the very moment the parties gave their acceptance and consent to the period fixed by the court, said period acquired the nature of a covenant; because the effect of such acceptance and consent by the parties is exactly the same as if they had expressly agreed upon it, and, it having been agreed upon by them, it became a law governing their contract, and it is evident that the court has no power to change or modify the same. Basis: Once fixed by the courts, the period cannot be changed by them. Classification of Obligations based on number of prestations (objects) Conjunctive Obligation • • Distributive Obligation • • ARTICLE 1199. A person alternatively bound by different prestations shall completely perform one of them. • Article 1200. The right of choice belongs to the debtor, unless it has been expressly granted to the creditor. The debtor shall have no right to choose those prestations which are impossible, unlawful or which could not have been the object of the obligation. (1132) Article 1201. The choice shall produce no effect except from the time it has been communicated. (1133) Article 1202. The debtor shall lose the right of choice when among the prestations whereby he is alternatively bound, only one is practicable. (1134) Questions as to who may exercise the right to choose which prestation is to be performed, as to when the choice becomes effective and as to the effect of loss of one or some of the prestations are required to be addressed. Alternative Obligation SECTION 3 Alternative Obligations The creditor cannot be compelled to receive part of one and part of the other undertaking. (1131) The various prestations are all due and demandable at the same time. Compliance may arise when the obligation involves several prestations but the debtor is requiring to perform only one prestation in order for the obligation to extinguished. There is more than one object (prestation), and the fulfillment of one is sufficient, determined by the choice of the debtor who generally has the right of election. The debtor is required to completely perform only one of them and such performance extinguishes the obligation. Right of Choice Who may Choose? • • • In the absence of a contrary agreement, it is the debtor who has the right to choose which of the available prestations he is to perform. The right of choice only be exercised by the creditor if he is expressly granted such right in the agreement of the parties. The right of choice may be granted to a third person by express agreement of the parties because said agreement is not prohibited by law nor contrary to morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. Page | 45 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 When choice or election becomes effective • The election becomes effective only from the moment that the same has been communicated to the other party. But when is the choice considered to have been communicated to the other party? Dean Capistrano The law does not require the creditor’s concurrence to the choice; if it did, it would have destroyed the very nature of alternative obligations, which empowers the debtor to perform completely one of them. Cognition Theory Effect of Choice • • The election or notice has no effect until it comes to the knowledge of the other party. Being followed under the Spanish Civil Code. Posting Rule or Mailbox Rule • • • Applying the cognition theory, the choice is deemed to have been communicated from the time that the other party gains knowledge of the election made by the other. If the right choice has been expressly granted to a third person, both the creditor and the debtor must be duly notified of the choice made by such third person. Note: In alternative obligations, the election becomes effective from the moment the choice is made known to the other party. What is required by Article 1201 is mere notice to the other party and not his consent. Ong Guan Can vs Century Insurance Co., Ltd. • • • Also called deposited acceptance An election made through a letter is effective from the time the notice is posted. The Civil Code of the Philippines has adopted the cognition theory. • • The object of the notice is to give the creditor the opportunity to express his consent, or to impugn the election made by the debtor. The election takes legal effect only when consented by the creditor, or if impugned by the latter, when declared proper by a competent court. • The right of election is extinguished when the party who may exercise that option categorically and unequivocally makes his or her own choice known. The choice becomes irrevocable and binding upon he who made it and he will not thereafter be permitted to renounce his choice and take an alternative which was at first open to him. As a consequence, the obligation ceases to be alternative and is converted into a pure or simple one. Limitations on Right of Choice • • • Whether the right of choice pertains to the debtor or to the creditor, he has no right to choose those prestations which are impossible, unlawful or which could not have been the object of the obligations The one who has the right of choice can still exercise his right because the obligation remains to be alternative, meaning there are still two or more prestations which can be performed. If all the prestations, except one, are impossible or unlawful, it follows that the debtor can choose and perform only one. Article 1203. If through the creditor's acts the debtor cannot make a choice according to the terms of the obligation, the latter may rescind the contract with damages. (n) Article 1204. The creditor shall have a right to indemnity for damages when, through the fault of the debtor, all the things which are alternatively the object of the obligation have Page | 46 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 been lost, or the compliance of the obligation has become impossible. Where loss is due to fortuitous events • The indemnity shall be fixed taking as a basis the value of the last thing which disappeared, or that of the service which last became impossible. • Damages other than the value of the last thing or service may also be awarded. (1135a) Article 1205. When the choice has been expressly given to the creditor, the obligation shall cease to be alternative from the day when the selection has been communicated to the debtor. • The alternative character of the obligation is retained if there are still tow or more prestations which subsist. Should only one prestation subsist while the others are lost by reason of a fortuitous event, the alternative character of the obligation ceases and obligation becomes a simple one. Should all prestations be lost by reason of a fortuitous event, the obligation is deemed extinguished provided that the lost occurs before the debtor has incurred in delay. Where loss is due to debtor’s fault Until then the responsibility of the debtor shall be governed by the following rules: • (1) If one of the things is lost through a fortuitous event, he shall perform the obligation by delivering that which the creditor should choose from among the remainder, or that which remains if only one subsists; • (2) If the loss of one of the things occurs through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may claim any of those subsisting, or the price of that which, through the fault of the former, has disappeared, with a right to damages; (3) If all the things are lost through the fault of the debtor, the choice by the creditor shall fall upon the price of any one of them, also with indemnity for damages. The same rules shall be applied to obligations to do or not to do in case one, some or all of the prestations should become impossible. (1136a) Effect of Loss of Object in Alternative Obligation • The effect of the loss of one, some or all of the prestation will depend on who has the right of choice and the reason for the loss of the same. • • • If the loss of one of the things occurs through the fault of the debtor and the right of choice belongs to the creditor, the latter may claim any of those subsisting, without the right to recover damages, or the price of the which, through the fault of the debtor, has disappeared, with a right to recover damages. The loss of one of the prestations has legal consequences because the creditor cannot make a choice according to the terms of the obligation by reason of the debtor’s fault. If the right of choice belongs to the debtor, the loss of the things by reason of his fault does not produce legal consequence because he may still perform that which remains of one only subsists. Should all the prestations be lost through the fault of the debtor, the creditor shall be entitled to recover the value of the last thing which disappeared or that of the service which last became impossible, which a right to recover damages other than the value of the last thing or service. If the right of choice belongs to the creditor and all the things are lost through the fault of the debtor, the choice by the creditor shall fall upon the price of any of them, also with indemnity for damages. Page | 47 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Where the Loss is Due to Creditor’s Fault • • If the loss of the thing occurs through the fault of the creditor and the right of choice belongs to the debtor, the latter may either: o Rescind the contract with damages. o Choose from among the remainder, if several prestation still subsist, or perform that which remains if one only subsists. If the right of choice pertains to the creditor, the loss of one of the things through his fault does not produce any legal consequences because the creditor may still choose from among the remainder, if several still subsist, or he may ask for the performance of that which remains if one only subsists. Loss After Election • Is one where only one prestation has been agreed upon but the obligor may render another in substitution. Facultative Obligation Only the prestation agreed upon is due and subject to the obligation but not the substitute which the debtor has reserved to himself the right to preform in lieu of the first. Only one prestation is due. The right of choice is always with the debtor. If the loss occurs after the choice has been duly communicated, the following rules shall apply: 1. If what was lost was the chosen prestation which, for all intents and purposes, is the only prestation which is due and demandable under the circumstances, the obligation is considered extinguished if it was lost without the fault of the debtor and before he has incurred in delay. If the same was lost by reason of the debtor’s fault, his obligation is converted to indemnification for damages. 2. If what was lost was not the chosen prestation, the same does not affect the obligation because said prestation is not what is due. Article 1206. When only one prestation has been agreed upon, but the obligor may render another in substitution, the obligation is called facultative. The loss or deterioration of the thing intended as a substitute, through the negligence of the obligor, does not render him liable. But once the substitution has been made, the obligor is liable for the loss of the substitute on account of his delay, negligence or fraud. (n) Facultative Obligation If the original prestation is impossible or unlawful, the obligation is rendered invalid even if the substitute prestation is valid. The loss of the substitute prestation prior to the election does not make the debtor liable even if the same is lost in his fault. Alternative Obligation All the prestations are due and subject to the obligation up to the time the election is made. Several prestations are due. The right of choice generally belongs to the debtor but may be granted to the creditor or to a third person. The fact that one of the prestation is impossible or unlawful does not affect the validity of the obligation. The loss of one of the prestations through the fault of the debtor prior to the election may render the debtor liable for damages (if the right of choice belongs to the creditor) Right of Choice and Effectivity of Election • • The debtor, by express argument, is granted the right to perform another prestation in substitution of the original prestation. Such right must be expressly agreed upon in the contract; otherwise, the obligation of the Page | 48 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • debtor is a simple one of performing that which is due. If the debtor intends to perform the original prestation he does not have to communicate such fact to the creditor because the latter is already expecting its performance considering that said prestation is what is due. If the debtor intends to perform the substitute prestation, his decision to perform the substitution prestation does not bind the creditor “except from the time it has been communicated” to the latter. Once the debtor has communicated to the creditor his decision to perform the other prestation, the choice becomes irrevocable and will bind both parties. As a consequence, the obligation ceases to be facultative in character and becomes a simple obligation of performing the chosen prestation. Effect of Loss of Substitute Prestation • • • • • • If the debtor did not communicate to the creditor that he would be performing the other prestation in lieu of what has been agreed upon, it is the original prestation which is due and not the substitute prestation. The loss of the substitute prestation, for whatever reason, does not affect the obligation to perform the original prestation. The loss of the substitute prestation by reason of fortuitous event does not affect the obligation for the simple reason that it is not what is due. Once the debtor has communicated to the creditor his decision to perform the other prestation, it is now the latter prestation which is due. Its lost will now have an effect upon the obligation. If it is lost by reason of the debtor’s fault, the debtor is liable for the loss of the same. If the same is lost without his fault and loss occur prior to him incurring delay, his obligation is extinguished. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 SECTION 4 Joint and Solidary Obligations Article 1207. The concurrence of two or more creditors or of two or more debtors in one and the same obligation does not imply that each one of the former has a right to demand, or that each one of the latter is bound to render, entire compliance with the prestation. There is a solidary liability only when the obligation expressly so states, or when the law or the nature of the obligation requires solidarity. (1137a) Article 1208. If from the law, or the nature or the wording of the obligations to which the preceding article refers the contrary does not appear, the credit or debt shall be presumed to be divided into as many shares as there are creditors or debtors, the credits or debts being considered distinct from one another, subject to the Rules of Court governing the multiplicity of suits. (1138a) Classification of bligation Based on Plurality of Subjects Joint Obligation Solidary Obligation Is one in which each debtor is liable for the entire obligation, and each creditor is entitled to demand the whole obligation. An obligation where there is a concurrence of several creditors, or of several debtors, or of several creditors and debtors, by virtue of which each of the creditors has a right to demand, and each of the debtor is bound to render, compliance with his proportionate part of the prestation which constitutes the object of the obligation. Each creditor can Each creditor may recover only his enforce the entire share of the obligation, and each Page | 49 creditor is entitled to demand only a proportionate part of the credit from each debtor. obligation, and each debtor may be debtor can be made obliged to pay it in to pay only his part. full. Meaning of Joint Obligation in Common law vs Civil Law Presumption in Favor of Joint Obligation • Common Law Every debtor in a joint obligation is liable in solidum for the whole; and the only legal peculiarity worthy of remark concerning the joint contract at common law is that the creditor is required to sue all the debtor at once. To avoid the inconvenience of the procedural requirement and to permit the creditor in a joint contract to do what the creditor in a solidary obligation can do, it is not unusual for the parties to a common law contract to stipulate that the debtors shall be “jointly and severally” liable. Civil Law Is equivalent to Spanish mancomunada simple mancomunada proper, where each debtor does not answer except for a part of total obligation, and to each creditor pertains only a part in the correlative rights. The term joint is equivalent to the apportionable joint obligation and solidary as to mancomunidad solidaria. Joint Obligations • • There is a concurrence of several creditors, or of several debtors, or of several creditors and debtors, by virtue of which each of the creditors has a right to demand, and each of the debtor is bound to render, compliance with his proportionate part of the prestation which constitutes the object of the obligation. Is one in which each debtor is liable only for a proportionate part of the debt, and the • In case of concurrence of two or more creditors or two or more debtors in one and the same obligation, and in the absence of express and indubitable terms characterizing the obligation as solidary, the presumption is that the obligation is only joint. It thus becomes incumbent upon the party alleging that the obligation is indeed solidary in character to prove such fact with preponderance of evidence for the wellentrenched rule is that solidary obligation cannot lightly be inferred. It must be positively and clearly expressed Example A, B, and C executed a promissory note where they say: “We bind ourselves to pay P900,000 to X.” Here, the obligation is presumed joint because it does not expressly provide for solidarity and neither the law nor the nature of the obligation requires solidarity in this situation. None of the three debtors may be obliged to pay the entire debt, as each is liable only to pay his share. Basis: solidarity among debtors supposes an abnormal increase of a person’s responsibility which includes that of another. Solidarity among creditors impresses greater confidence among them because each may enforce the whole obligation. • • • Between the abnormal and excessive responsibility in solidary obligation and the common and normal liability in joint, the law presumes in favor of join obligation. When it is not provided in a judgement that the defendants are liable to pay jointly and severally a certain sum of money, none of them may be compelled to satisfy in full said judgement. Even when the body of the court’s decision characterizes the liability of the defendants as solidary but in the dispositive portion thereof the word solidary neither appears nor can it be inferred therefrom; the liability of the defendants is merely joint. Page | 50 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • When there is a conflict between the dispositive part and the opinion of the court contained in the text or body of the decision, the former must prevail over the latter on the theory that the dispositive portion is the final order, while the opinion is merely a statement ordering nothing. Correlativity of Credits and Debts in Joint Obligations In obligation with a plurality of debtors and a plurality of creditors. Who shall the be considered the creditor for each debtor and vice versa? • Division of Joint Credits and Debts • If the law or the obligation itself is silent as to how the debt and the credit shall be divided among the joint debtors or the joint creditors, the same shall be divided into as many equal shares as there are creditors or debtors. Example: A, B, and C bound themselves to pay P900, 000 to X. Here, the amount of the debt shall be understood to be divided into three equal parts, and consequently, each of the debtors has to pay P300, 000 to creditor X, since their respective share in the obligation has not been determined. • The principle also applies when plurality exists both with respect to the debtors and creditors, not only to situations where there are several joint creditors and one debtor or where there are several joint debtors and one creditor. Example: A, B, and C are joint debtors of X, Y, and Z, also joint creditors, for the sum of P900, 000. As to debtors A, B, and C, the debt should be divided into three equal parts, such that each of them shall be liable to pay P300, 000 only. As to creditors X, Y, and Z, the credit shall also be divided into three equal parts, such that each one of them shall be entitled to demand the amount of P300, 000 only. • The division of joint credits and debts may be established in the obligation itself, in which case there can be no question as to such division. Example: A, B, and C bound themselves to pay P900, 000 to X. In their obligation, it ws specified that A is to pay X P500, 00, B P300, 000, and C P100,000. If the amount of the debt of one of the debtors coincides with the credit of one of the creditors, the former must therefore be the debtor of the latter. Example: the respective shares of joint debtors A, B, and C in the debt are as follows: P3, 000, P2, 000, P1,000; while the respective shares of joint creditors X, Y, and Z are as follows: P1, 000, P2, 000, and P3, 000. Here, the credits and debts can be matched, as follows: Z to A, Y to B, and X to C. When the number of creditors is greater or less that that of the debtors or vice versa; or when, although there is an equal number of credits and debts, they are unequal to each other and they do not match. • Each creditor may ask or each debtor may pay all in proportion to the respective credits and debts. Example #1: A, B, and C are indebted to X and Y for P900, 000. Applying the presumption of equal sharing in the debt and credit, the debt shall be divided into three equal parts, such that each of the debtor owes 1/3 of the debt. The credit, in turn, shall also be divided into two equal parts, and consequently, each of the creditors owns ½ of the credit. Therefore, X may demand from A ½ of 1/3, i.e., ½ of P30, 000, or P15,000; from B, also P15, 000 and from C, another P15, 000. The same solution applies to Y in collecting from A, B, and C. Example #2: A and B are indebted to X and Y for the sum of P900,000. The share of A in the debt is 1/3 or P30, 000, while the share of B is 2/3 or P60, 000. X, in turn, owns ¾ of the credit or P67, 500, while Y own 1.4 of the credits or P22, 500. Here, the solution is as follows: X may demand from A ¾ of 1/3, i.e., ¾ of P30, 000, or P22, 500; and X may collect from B ¾ of 2/3, i.e., ¾ of P60, 000, or P45, 000. Y, in turn, may collect from A ¼ of 1/3, i.e., ¼ of Page | 51 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 P30, 000, or P7, 500; Y may collect from B ¼ of 2/3, i.e., ¼ of P60, 000, or P15, 000. • The solution that each creditor may ask or each debtor may pay all in proportion to the respective credits and debts should also apply to a situation where there is an equal number of credit and debt are presumed equal. Consequences or Effects of Joint Character of Obligation • • • • The most fundamental effect of joint obligations is that each creditor can demand only for the payment of his proportionate share of the credit, while each debtor can be held liable only for the payment of his proportionate share of the debt. Joint creditor cannot act in representation of others. Neither can a joint debtor be compelled to answer for the liability of the others. The extinction of the debt of one of the various debtors does not necessarily affect the debts of the others. Prescription, novation, merger, and any other cause of modification or extinction does not extinguish or modify the obligation except with respect to the creditor or debtor affected, without extending its operation to any other part of the debt or of the credit. In view of this essential characteristics of joint obligation, the following effects shall be produced: 1. The interruption of prescription by the claim of creditor addressed to a single debtor or by an acknowledgement made by one of the debtors in favor of one or more of the creditors is not to be understood as prejudicial to or I favor of the other debtors or creditors. 2. The delay on the part of only one of the joint debtors does not produce effects with respect to the others, and if the delay is produced through the acts of only one of the joint creditors, the others cannot take advantage thereof. 3. The vices of each obligation arising from the personal defect of a particular debtor or creditor, do not affect the validity of the other credits or debts. 4. The insolvency of one debtor or his nonperformance does not increase the liability of his co-debtors, nor authorize the creditor of the defaulting debtor to claim anything from his co-debtors. 5. In the divisible joint obligation, the defense of res judicata is not extended from one debtor to another. Article 1209. If the division is impossible, the right of the creditors may be prejudiced only by their collective acts, and the debt can be enforced only by proceeding against all the debtors. If one of the latter should be insolvent, the others shall not be liable for his share. (1139) Article 1210. The indivisibility of an obligation does not necessarily give rise to solidarity. Nor does solidarity of itself imply indivisibility. (n) Joint Indivisible Obligations Solidarity and Indivisibility • Article 1210 expressly clarifies that the indivisibility of an obligation does not necessarily give rise to solidarity nor does solidarity of itself imply indivisibility. Solidarity Refers to the vinculum or legal tie that binds the parties and, consequently therefore, to the subjects of the obligation. Requires plurality of subjects. The solidarity remains even when there has been nonperformance of the debtors who Indivisibility Refers to the prestation or objects of the obligation. If the prestation is incapable of partial performance, the obligation is indivisible. Does not require plurality of subjects. In case of breach, the obligation is converted into payment of damages and the Page | 52 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 become liable for reason for damages. indivisibility ceases to exist. Effect of Breach of joint indivisible obligation • Concept of Joint Indivisible Obligation • • If in case plurality of subjects, each creditor cannot demand more than his part or each debtor cannot be required to pay more than his share and the prestation is, at the same time, incapable of partial performance, the obligation becomes a joint indivisible one. The presumption that the obligation is merely joint still applies in case of plurality of creditors or debtors even when the obligation is indivisible in nature. Example: A and B obliged themselves to deliver a horse to X, the obligation of A and B to X is still presumed to be joint. As a consequence, neither of them is liable to perform the entire obligation because each is liable only for his part. Therefore, in case one of them becomes insolvent later on, the other debtor does not become liable for the share of the insolvent debtor. • • • • • • • Indivisible Solidary Obligation • The collective action of all debtors is necessary in order for the obligation to performed, although each answering only for his part. Thus, Article 1209 provides that this kind of obligation, the debt can be enforced only by proceeding against all the debtors. In order to make an effective demand the same must be against al the debtors. The same principle applies on case of plurality of creditors. While Article 1209 states that the right of the creditor may be prejudiced only by their collective acts, which may give rise to the inference that if the act is beneficial, i.e., such as interrupting the running of the period of prescription, the act of one may be deemed sufficient, the fact remains that in a joint obligation neither of the creditors may represent the others because the credits are considered distinct from one another. Hence, the act of one alone is ineffective even if such act is beneficial to the others. Since the collective action of all debtors is necessary to enforce a joint indivisible obligation, the obligation is considered breached form the time anyone of the debtors does not comply with his undertaking, in which case, the obligation is converted into payment of damages. The reason for the indivisibility ceases to exist and each debtor becomes liable for his part of the indemnity. Those debtors who are not guilty of such breach and were ready to preform their part of the obligation are not liable to pay damages and their liability is limited to their corresponding portion of the price of the thing or of the value of the service constituting the obligation. In the event that one of the debtors becomes insolvent, the others shall not be liable for his share. • In the event of the non-performance of the obligation, the creditor may proceed against any debtor for the payment of the indemnity, including the price of the thing or the value of the service constituting the obligation and the damages, even if the latter was ready and willing to perform. He may recover the damages from the debtor who was responsible for the breach of the obligation, in addition to his right to recover from the others their respective shares in the price. Article 1211. Solidarity may exist although the creditors and the debtors may not be bound in the same manner and by the same periods and conditions. (1140) Solidary Obligations When Solidary Liability Exists • When there is a concurrence of two or more debtors under a single obligation, obligation is presumed to be joint. The law further Page | 53 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 provides that to consider the obligation as solidarity in nature, it must expressly be stated as such, or the law or the nature of the obligation itself must require solidarity. Nature of Obligation Requires Solidarity • Solidary Liability by Express Stipulation • • • There is solidary liability when the obligation expressly so states. It is not necessary that the agreement should use precisely the word “solidary” for an obligation to be so; it is sufficient that the stipulation states for example, that each of the debtors can be compelled to pay the totality of the debt, or that each of them is obligated to the entire value of the obligation. • Equivalent terms may in fact be employed by the parties to indicate the existence of solidary liability, as follows: 1. The terms of a contract govern the rights and obligations of the contracting parties. When the obligor or obligors undertake to be jointly and severally liable, it means that the obligation is solidary. When the promissory note expressly states that the three signatories therein are jointly and severally liable, any one, some or all of them may be proceeded against for the entire obligation. 2. The phrase juntos o separadamente, used in the promissory note, is an express statement, making each of the persons who signed it individually liable for the payment of the full amount of the obligation contained therein. 3. The words individually and collectively have also been held to create a solidary liability. 4. When a promissory containing the word, I promise to pay is signed by two or more persons, they are deemed to be jointly and severally liable thereon. • • Far Eastern Shipping Company vs Court of Appeals • • • Solidary Liability Imposed by Law (See page 173-174) Article 1210 clarifies the concept of solidary liability by stating that the indivisibility of an obligation does not necessarily give rise to solidarity. The facts that the obligation is indivisible does not necessarily give rise to solidarity in the absence of express and indubitable terms characterizing the obligation as solidary. Some of the obligations, solidary by nature, are also provided by law, such as the civil liability of the principals, accomplices, and accessories in the commission of a crime, each within their respective class; the responsibility of two or more persons who are liable for a quasi-delict; the obligations of two or more bailees in a contract of commodatum, as well as the obligations of two or more officious managers unless the management was assumed to save the thing or business from imminent danger. The nature of the obligation of the coconspirators in the commission of the crime requires solidarity, and each debtor may be compelled to pay the entire obligation. Joint tortfeasors are solidary liable for the resulting damage. Joint tortfeasors are each liable as principals, to the same extent and in the same manner as if they had performed the wrongful act themselves. It would not be an excuse for any of the joint tortfeasors to assert that his or her individual participation in the wrong was insignificant as compared to those of the others. The damage cannot be apportioned among them, except by themselves. They are jointly and severally liable for the whole amount. Liwanag vs Commission • Workmen’s Compensation In compensation cases, the liability of business partners should be solidary; Page | 54 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 otherwise, the right of the employee may be defeated, or at least crippled. Sunga-Chan vs CA • • When several heirs of a deceased partner continued with the business and management of the partnership against the will of the other partner, the obligation of said heirs to undertake an inventory, render an accounting of partnership affairs is solidary by its nature. Since the acts complained of were not severable in nature, it was impossible to draw the line between when the liability of the other starts. debtor may be compelled to pay the entire obligation to the creditor. Solidarity Not affected by varied terms and Condition • • • Kinds of Solidarity Active Solidarity • • Is one that exist only among the creditors. The same may be established only by the agreement of the parties. • Passive Solidarity • • Exists only among the debtors. May be established by the will of the parties expressed in a contract or imposed by law or derived from the nature of the obligation itself. • Exists among the creditors and debtors. It may be possible for the obligation to be joint on the side of the creditors and solidary on the side of the debtors Each creditor can demand only his share in the obligation but each It may be possible for the obligation to be solidary on the side of the creditors but joint only on the side of the debtors. Each creditor can demand the performance of the entire obligation but The legal bond of solidarity is not destroyed by the mere fact that the parties are not bound by the same periods and conditions. The vinculum or bond which binds the creditors and the debtors in solidary obligations may be uniform, when they are bound by the same terms and conditions, or varied, when they are not bound by the same terms and conditions. Solidarity is still preserved by recognizing in the creditor the power, upon the happening of the condition or the arrival of the term, to claim this remaining portion from any of the debtors. A solidary debtor may avail himself not only of defenses which are derived from the nature of the obligation and of those which are personal to him or pertain to his share, but also of defenses which personally belong to another solidary debtor as regards that part of the debt for which such other solidary debtor is responsible. Inchausti $ Co. vs Yulo • Mixed Solidarity each debtor may only be compelled to pay his share in the obligation. Even though the creditor may have stipulated with some of the solidary debtors diverse installments and conditions, this does not lead to the conclusion that the solidarity stipulated in the instrument is broken because “solidarity may exist even though the debtors ae not bound in the same manner and for the same periods and under the same conditions.” Article 1212. Each one of the solidary creditors may do whatever may be useful to the others, but not anything which may be prejudicial to the latter. (1141a) Article 1213. A solidary creditor cannot assign his rights without the consent of the others. (n) Page | 55 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1214. The debtor may pay any one of the solidary creditors; but if any demand, judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by one of them, payment should be made to him. (1142a) • Article 1215. Novation, compensation, confusion or remission of the debt, made by any of the solidary creditors or with any of the solidary debtors, shall extinguish the obligation, without prejudice to the provisions of article 1219. The creditor who may have executed any of these acts, as well as he who collects the debt, shall be liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. (1143) Article 1212 and Article 1215 • Active Solidarity Effects of Active Solidarity Active Solidarity or Solidarity among the debtors • • A time among several creditors of the same obligations, by virtue of which, each of them, as regards his co-creditors, is creditor only as to his share in the obligation and, in regard to the common debtor, he represents all of them. The effects of active solidarity will depend on whether the relationship under consideration is between the solidary creditors and debtors or between the solidary creditors themselves. • In relation to acts which are clearly beneficial to the other solidary creditors, the mutual agency is pronounced, not only in so far as the debtors are concerned but even among the solidary creditors themselves. • Consequently, each solidary creditor may interrupt the period of prescription, place the debtor in default by making a proper demand or bring a suit so that the obligation may produce interest. Mutual Agency • • The essence of active solidarity. Every creditor is considered an agent of the others and he has the power to claim and exercise the rights of all of them in relation to their debtor or debtors. Each creditor is entitled to demand the whole obligation. In relation to their debtors, each creditor is considered an agent of the others whether the act executed by him is beneficial to cocreditors or prejudicial to them. However, in so far as the relationship existing among the While Article 1212 prohibits a solidary creditor from doing anything that may be prejudicial to the others, this does not mean that the precept contained in said article is inconsistent or contradictory with the rule embodied in Article 1215 that the novation, compensation, confusion or remission of the debt made by any of the solidary creditors shall extinguish the obligation. Article 1215 sanctions the efficacy of such prejudicial acts only insofar as it affects the debtors, but that with relation to the creditors, Article 1212 means that none of the said creditors can execute any act prejudicial to the others without at the same time incurring the obligation of indemnifying the latter. • Effects Among Solidary Creditors • • solidary creditors themselves, their mutual agency extends only to acts which are beneficial to the others, but not to anything which may be prejudicial to them. While each solidary creditor may extinguish the obligation by novation, compensation, confusion, remission, or any other mode, the creditor who may have executed any of these acts shall be liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. Quiombing vs CA • Suing for the recovery of the contract price is certainly a useful act that the plaintiff solidary creditor could do by himself alone. Page | 56 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • Where the obligation of the parties is solidary, either one of the parties is indispensable, and the other is not even necessary (now proper) because complete relief may be obtained from either. The complainant having been filed by the plaintiff solidary creditor; whatever amount is awarded against the debtor must be paid exclusively to him. If the plaintiff eventually collects the amount due from the solidary debtors, the other solidary creditor may later claim his share thereof, but that decision is for him alone to make. Effects of Unauthorized assignment of right • • • • Article 1213 prohibits the assignment of rights of a solidary creditor without the consent of the others, The rule is premised on the existence of mutual agency among the creditors, which implies mutual confidence in them, in addition to the power of every solidary creditor to cause the extinguishment of the debtor’s obligation without the knowledge and consent of the others. The prohibition applies therefore only when the assignment is made to a third person with whom confidence has not been reposed by the other co-creditors, but not if the assignment is made to a co-creditor because the reason for the prohibition does not exist. Any payment made by the debtor and debtors to such assignee is a payment made to a stranger and, therefore, invalid as a rule. The debtor may recover, however, from the assignee the undue payment on the basis of an accion in rem verso. 2. Any solidary creditor may extinguish the obligation by novation, compensation, confusion, remission or any other mode of extinguishment; but the creditor who may have executed any of these acts shall be liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding. Effect of Demand by Solidary Creditor • • • In view of the mutual agency existing among the solidary creditors, their debtor or debtors may pay any one of them. However, if any demand, whether judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by any of the solidary creditors, payment should be made to him. Any payment made by the debtor upon whom the demand has been made to any other creditor is not valid and does not extinguish the obligation. As a consequence, the demanding creditor can require the debtor to pay again. The remedy of the debtor in this situation is to recover the erroneous payment from the other creditor to whom such payment has been made. Mixed Solidarity • • • Effects Between Solidary Creditors and Debtors The effects of active solidarity as between th solidary creditors and their debtors are as follows: The rule is that each creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them simultaneously and each debtor may pay one of the solidary creditors. However, when demand, whether judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by anyone of the solidary creditors to anyone of the solidary debtors, payment should be made only to the demanding creditor. The prohibition does not affect the other debtors upon whom no demand has been made, and hence they can make payment to any other creditor who did not make the demand. Effects of Extinguishment of Obligation 1. The debtors may pay any one of the solidary creditors; but if any demand, judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by one of them, payment should be made to him. • The act of extinguishment of obligation, which is obviously prejudicial to the cocreditors, is valid insofar as the debtors are concerned and extinguishes the latter’s Page | 57 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 obligation; but the creditor who may have executed such prejudicial act shall be liable to his co-creditors for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. by subsequent instrument, covenanted with some of the solidary debtors’ different periods of payment and different conditions, did not destroy the solidary stipulated in the original contract. The effects of such prejudicial acts are as follows: Novation Rule for A Surety • • • • 1. 2. 3. 4. • May either be extinctive or modificatory. It is extinctive when an old obligation is terminated by the creation of a new obligation that takes the place of the former; it is merely modificatory when the old obligation subsists to the extent it remains compatible with the amendatory agreement. An extinctive result either by changing the object or principal conditions (objective or real), or by substituting the person of the debtor or subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor (substantive or personal). Under this mode, novation would have dual functions – one to extinguish an existing obligation, the other to substitute a new one in its place – requiring a conflux of four essential requisites: A previous valid obligation An agreement of all parties concerned to a new contract The extinguishment of the old obligation The birth of a valid new obligation Whether the novation consists in the substitution of the person of the debtor or in the subrogation of a third person in the rights of the other creditors, the solidary creditor who effects the novation shall be liable to his co-creditors for their shares in the obligation. • Reason: an extension of time given to the principal debtor by the creditor without the surety’s consent would deprive the surety of his right to pay the creditor and to be immediately subrogated to the creditor’s remedies against the principal debtor upon the maturity date. Compensated and Merger • • • Rule for Passive Solidarity • An extension of time granted by the creditor to a solidary debtor does not release the others from the obligation. Inchausti & Co. vs Yulo • The extension of time granted to several solidary debtors and the fact that the creditor, An extension granted to the debtor by the creditor without the consent of the surety extinguishes the suretyship. • • Compensation is a mode of extinguishing the concurrent amount the debts of persons who in their own right are creditors and debtors of each other. Compensation presupposes two persons who, in their own right and as principals, are mutually indebted to each other respecting equally demandable and liquidated obligations over any of which no retention or controversy commenced and communicated in due time to the debtor exists. When the two debts are of the same amount, there is a total compensation. Thus, in the case of total compensation the obligation is extinguished and the relation between creditors as a group and debtors as another group ceases, and there is left only the resulting liability for reimbursement within each group. When the compensation is partial, and there is doubt as to what part of the debt it should be applied, the rules on the application of payment should govern. In confusion or merger, the obligation is extinguished when the characters of creditor and debtor are merged in the same person. Page | 58 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • In solidary obligations, the extinguished is limited to the portion or share corresponding tot the creditor or debtor in whom the two characters concur. The solidary creditor in whom confusion has taken place remains liable to the other solidary debtor who acquires the whole credit, he can still demand from the other debtor who acquires the whole credit, he can still demand from the other debtors their respective shares therein. Effect of Payment Made to Solidary Creditor • • • Remission or Condonation • • • • • • Remission or condonation is an act of liberality on the part of the creditor, who receives no price or equivalent thereof, renounces the enforcement of the obligation, which is extinguished in its entirety or in that part or aspect of the same to which the remission refers. To be valid, it requires the acceptance of the debtor. When the remission is effected by only one of the solidary creditors, he becomes liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. When several, but not all, of the creditors make the remission, there can be no action as between those who made it; but all of them will be liable for the shares of the creditors who did not remit, and if one is insolvent, his share shall be made up by the others who concurred in the remission. The creditor who converted the solidary character of the obligation 0f the debtors into a joint one does not immediately become liable to the other solidary creditors because the obligation of the debtors is not extinguished yet. If one of the joint debtors will eventually become insolvent, in which case the other joint creditors do not become liable for the part of the insolvent debtor, the creditor who effected such conversion shall be liable to the others for their corresponding share in the debt of the insolent debtor. In active solidary, the debtor may pay any one of the solidary creditors unless a demand has been made by one of the creditors, in which case payment should be made to him. The creditor who may have collected the debt shall be liable to his co-creditors for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. As a consequence, the creditor who has collected the debt is converted into a debtor liable to his co-creditor for the share corresponding to each of the latter. Article 1216. The creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them simultaneously. The demand made against one of them shall not be an obstacle to those which may subsequently be directed against the others, so long as the debt has not been fully collected. (1144a) Article 1217. Payment made by one of the solidary debtors extinguishes the obligation. If two or more solidary debtors offer to pay, the creditor may choose which offer to accept. He who made the payment may claim from his co-debtors only the share which corresponds to each, with the interest for the payment already made. If the payment is made before the debt is due, no interest for the intervening period may be demanded. When one of the solidary debtors cannot, because of his insolvency, reimburse his share to the debtor paying the obligation, such share shall be borne by all his co-debtors, in proportion to the debt of each. (1145a) Article 1218. Payment by a solidary debtor shall not entitle him to reimbursement from his codebtors if such payment is made after the obligation has prescribed or become illegal. (n) Page | 59 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Passive Solidarity Mutual Guaranty Passive solidarity or solidarity among the debtors • • • • Is a tie or vinculum among several debtors, by virtue of which each of them, in relation to his share in the obligation, but in relation to the common creditor or creditors, he is bound to the payment of the whole credit. Each debtor can be made to answer for the shares of the others. There exists among the solidary debtors a case of mutual guaranty with respect to the shares of the co-debtors. A solidary debtor acquires the right to demand reimbursement from the others for their corresponding shares once payment of the entire obligation has been made. Distinguished from suretyship • • Solidarity signifies that the creditor can compel any one of the solidary debtors or the surety alone to answer for the entirety of the principal debt. However, while a guarantor may bind himself solitarily with the principal debtor, thereby becoming a surety, the liability of a guarantor is different from that of a solidary debtor. Solidary Codebtor A solidary co-debtor has no other rights than those bestowed upon him in Section 4, Chapter 3, Title I, Book IV of the Civil Code. Surety Outside of the liability he assumes to pay the debt before the property of the principal debtor has been exhausted, retains all the other rights, actions and benefits which pertain to him by reason of the fiansa. The civil law The Civil Law relationship existing suretyship is, between the codebtors liable in solidum is similar to the common law suretyship. The solidary debtor who effected the payment to the creditor may claim from his co-debtors only the share which corresponds to each, with the interest for the payment already made. Such solidary debtor will not be able to recover from the co-debtors the full amount already paid to the creditor, because the right to recovery extends only to the proportional share of the other codebtors, and not as to the particular proportional share of the solidary debtor who already paid. Reason: solidary debtor answer not only for another’s debt but also for his own. The extension of time granted by the creditor to a solidary debtor does not release the others from the obligation. accordingly, nearly synonymous with the common law guaranty. Even as the surety is solitarily bound with the principal debtor to the creditor, the surety who does pay the creditor has the right to recover the full amount paid, and not just any proportional share, from the principal debtor or debtors. Such right to full reimbursement falls within the other rights, actions and benefits which pertain to the surety by reason of the subsidiary obligation assumed by the surety. Reason: in the case of the surety, he alone answers for another’s debt. An extension of time granted to the debtor by the creditor without the consent of the surety extinguishes the suretyship. Page | 60 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Inciong, Jr. vs Court of Appeals • The liability of a surety is different from that of solidary debtor and that Inciong signed the promissory note as solidary co-maker (debtor) and not as a guarantor. Because the promissory note involved in the case expressly states that the three signatories therein are jointly and severally liable, any one, some or all of them may be proceeded against for the entire obligation and the choice is left to the creditor to determine against whom he will enforce collection. Pursuant to the rule that a creditor may sue any of the solidary debtors, it is clear that solidarity does not make a solidary obligor an indispensable party in a suit filed by the creditor. De Castro vs CA • • Remedies Against Solidary Debtors • • • When the obligation is solidary, the creditor may bring his action in toto against the debtors obligated in solidum. The creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them simultaneously. The choice is left to the solidary creditor to determine against whom he will enforce collection. The solidary liability of the four co-owners militates against the theory that the other coowners should be impleaded as indispensable parties. When the law expressly provides for solidary of the obligation, as in the liability of coprincipals in a contract of agency, each obligor may be compelled to pay the entire obligation because Article 1216 of the Civil Code provides that a creditor may sue any of the solidary debtors. La Yebana Co., Inc. vs Valenzuela • When the guarantor binds himself solitarily within the principal debtor to pay the latter’s debt to his creditor, he cannot and should not complain that the creditor should thereafter proceed against him to collect its credit. Dimayuga vs PCI Bank • Since the obligation of the debtors is solidary, there is nothing improper in the creditor’s filing of an action against the surviving the solidary debtors alone, instead of instituting a proceeding for the settlement of the estate of the deceased debtor wherein his claim could be filed. Philippine National Bank vs Asuncion • • Nothing in Section 6 of Rule 86 prevents a creditor from proceeding against the surviving solidary debtors. The choice is undoubtedly left to the solidary creditor to determine against whom he will enforce collection. In case of death of one of the solidary debtors, he (the creditor) may, if he chooses, proceed against the surviving solidary debtors without necessity of filing a claim in the estate of the deceased debtors. Reason: the creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or against all of them simultaneously, the fact that an action had been instituted or that payment had been enforced against one of them not being a bar thereto as long as there remains a balance to collect. Bicol Savings & Loan Association vs Guinhawa The bringing of an action against the principal debtor to enforce the payment of the obligation is not inconsistent with, and does not preclude, the bringing of another action to compel the surety to fulfill his obligation under the agreement. Effect of Payment by Solidary Debtor Extinguishment of Obligation • If two or more solidary debtors offer to pay, the creditor may choose which offer to accept. Page | 61 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • If there is also solidarity on the side of the creditors, a solidary debtor may pay to any one of the solidarity creditors, except when demand is made on said solidary debtor, his payment, in order to be valid and effective, must be made to such demanding creditor. Upon payment made by one of the solidary debtors of the entire obligation, said obligation is extinguished and the juridical tie between the creditor or creditors and the solidary debtors is dissolved thereby. Effects of Payment by Solidary Debtor • • • • • Payment made by one of the solidary debtors extinguishes the obligation and the juridical tie between the creditor on the one hand, and the solidary debtors, on the other, is dissolved thereby. After such payment, Article 1217 gives to a solidary debtor who has paid the entire obligation the right to be reimbursed by his co-debtors for the share which corresponds to each; provided, however, that such payment is made before the obligation has prescribed or become illegal. If such payment is made after the obligation has prescribed or become illegal, the payment by a solidary debtor shall not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors. Where one of several persons who are send upon a joint and several liability elects to pay the whole, such person is subrogated to the rights of the common creditor and may properly be substituted in the same action as plaintiff for the purposes of enforcing contribution from his former associates under article 1145 of the old Civil Code. If a solidary debtor pays the obligation in part, he can recover reimbursement from the codebtors only in so far as his payment exceeded his share in the obligation. Reason: if a solidary debtor pays an amount equal to his proportionate share in the obligation, then he in effect pays only what is due from him. If the debtor pays less than his share in the obligation, he cannot demand reimbursement because his payment is less than his actual debt. What if, after payment, one of the solidary debtors become insolvent, how may the same affect the right of the debtor who paid the entire obligation to demand reimbursement? • The third paragraph of Article 1217 states that the share of the insolvent debtor shall be borne by all of the co-debtors, including the debtor who has paid the debt and who is seeking reimbursement, in proportion to the debt of each. Distinguished from reimbursement • right of surety to The moment the surety fully answers to the creditor for the obligation created by the principal debtor, such obligation is also extinguished. At the same time, the surety may seek reimbursement form the principal debtor for the amount paid, for the surety does in fact become subrogated to all the rights and remedies of the creditor. Joint and Several Debtor Article 1217 makes plain that the solidary debtor who effected the payment to the creditor may claim from his co-debtors only the share which corresponds to each, with the interest for the payment already made. Such solidary debtor will not be able to recover from the co-debtors the full amount already paid to the creditor, because the right to recovery extends only to the proportional share of the other codebtors, and not as Surety As surety is solidary bound with the principal debtor to the creditor, the surety who does pay the creditor has the right to recover the full amount paid, and not just any proportional share, from the principal debtor or debtors. Such right to full reimbursement falls within the other rights, actions and benefits which pertain to the surety by reason of the subsidiary obligation assumed by the surety. Page | 62 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 to the particular proportional share of the solidary debtor who already paid. • The remission of the debt may either be for the whole obligation, or for the full share of the affected debtor, or only for a part of the share of the affected debtor. Remission of Whole Obligation What is the source of this right to full reimbursement by the surety? • • • • His right is based on Article 2066 which assures that the grantor who pays for a debtor must be indemnified by the latter, such indemnity comprising of, among others, the total amount of the debt. Article 2067 establishes that the guarantor who pays is subrogated by virtue thereof to all the rights which the creditor had against the debtor. While the surety who fully answers to the creditor for the obligation becomes subrogated to all the rights and remedies of the creditor, payment by one solidary debtor does not create a real case of subrogation because the original obligation is extinguished and a new one is created. While the creditor may collect the whole amount of the loan from anyone of the solidary co-debtors the payment made by one of the solidary debtors entitles him to claim from his co-debtors only the share pertaining to each with interest on the amount advanced. Article 1219. The remission made by the creditor of the share which affects one of the solidary debtors does not release the latter from his responsibility towards the co-debtors, in case the debt had been totally paid by anyone of them before the remission was effected. (1146a) Article 1220. The remission of the whole obligation, obtained by one of the solidary debtors, does not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors. (n) Effects of Remission in Passive Solidarity • • • A total remission has the effect of extinguishing the obligation. But the remission of the whole obligation, obtained by one of the solidary debtors, does not entitle him to reimbursement form his codebtors, because the remission is a gratuitous act. If there is also solidarity on the side of the creditors and the remission is made by only one of them, the obligation is extinguished in the amount and to the extent in which it is made; but the creditor who made the remission becomes liable to his co-creditors for their shares. If the remission is made by several, but not all, of the creditors, there can be no action as between those who made it; but all of them will be liable for the shares of the creditors who did not remit, and if one is insolvent, his share will have to be borne by those who concurred in the remission. Remission of Solidary Debtor’s Share • • • If the remission is for the solidary debtor’s full share, he ceases to have any relation with the creditors, from whom he is thereby released, unless the continuation of his solidary relation has been expressly reserved, in which case he will be a surety for the debtors. The balance of the debt may not be collected from him by any one of the solidary creditors. If the remission in favor of a solidary debtor is only partial, not covering his full share, his character a solidary debtor continues with respect to the creditors and his co-debtors. As a consequence, the balance of the debt can still be collected from him by any one of the solidary creditors. Whether the remission shall involve the full or only a portion of the share of the affected solidary debtor, the latter shall not be Page | 63 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 released from his personality towards the codebtors, in case the debt had been totally paid by anyone of them before the remission was effected. • • Article 1221. If the thing has been lost or if the prestation has become impossible without the fault of the solidary debtors, the obligation shall be extinguished. • If there was fault on the part of any one of them, all shall be responsible to the creditor, for the price and the payment of damages and interest, without prejudice to their action against the guilty or negligent debtor. If through a fortuitous event, the thing is lost or the performance has become impossible after one of the solidary debtors has incurred in delay through the judicial or extrajudicial demand upon him by the creditor, the provisions of the preceding paragraph shall apply. (1147a) Effect of Loss of thing impossibility of performance or supervening Paragraph 1, Article 1221. If the thing has been lost or if the prestation has become impossible without the fault of the solidary debtors, the obligation shall be extinguished. • • • • The provision contemplates of an obligation to deliver a determinate thing and an obligation to do. Even if the thing is lost or the performance has become impossible by reason of fortuitous event, the obligation is not extinguished if the loss or impossibility of performance occurred after one of the solidary debtors has incurred in delay through the judicial or extrajudicial demand upon him by the creditor. The same rule applies if the thing has been lost or the performance has become impossible by reason of the fault of any one of the solidary debtors. In case of breach of a solidary obligation, all debtors are liable to the creditor for the price and the payment of damages and interest. The damages paid by a solidary debtor who was not responsible for the breach of the obligation may be recovered in toto from the guilty or negligent debtor. The other creditors cannot be made to pay in excess of their normal contribution. In case of breach of a joint indivisible obligation where only the joint debtor responsible for the breach shall be liable to the creditor for the payment of damages while those joint debtors who may have been ready to fulfill their undertaking shall not contribute to the indemnity beyond the corresponding portion of the price of the thing or of the value of then service in which the obligation consists. Article 1222. A solidary debtor may, in actions filed by the creditor, avail himself of all defenses which are derived from the nature of the obligation and of those which are personal to him, or pertain to his own share. With respect to those which personally belong to the others, he may avail himself thereof only as regards that part of the debt for which the latter are responsible. (1148a) Defenses Available to Solidary Debtors In actions filed by the creditor, a solidary debtor may invoke three kinds of defenses: 1. Those which are derived from the nature of the obligation. 2. Those which are personal to the debtor being sued or pertaining to his share. 3. Those which belong to his co-debtors. • The foregoing defenses are also available to a surety who binds himself solidarily liable with the principal debtor, pursuant to Article 2047 which specifically calls for the application of the provisions on joint and solidary obligations to suretyship contracts. Luzon Surety Co., vs De Marbella • The petitioner is liable on its bond does not, however, mean that execution may issue against it without prior notice of the action or proceeding to hold it liable on its bond, and Page | 64 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 without giving it its day in court. The solidary nature of its liability as surety on the receiver’s bond does not imply that it can be condemned to pay without a hearing. Solidarity simply dispenses with the necessity of levying first upon the property of the principal. Defense Arising from Nature of Obligations • Defenses which arises from the nature of the obligation are all those connected with the obligation and which may contribute to weaken or destroy the vinculum juris existing between the creditor and the principal debtor. (See examples on page 206) Defenses Personal to Debtor Being Sued There are two kinds of defenses which are personal to the debtor being sued: 1. Those affecting the capacity or consent of the debtor being sued, such as minority, insanity, mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud. 2. Those referring particularly to his portion of the obligation, such as special terms or conditions pertaining to his share alone because solidarity may still exist although the creditors and debtors may not be bound in the same manner and by the same terms and conditions. • • The first kind of defense will completely absolve the defendant solidary debtor from any liability to the creditor. The second kind of defense constitutes only a partial exemption from liability since they may be utilized only with respect to the part of the obligation corresponding to the debtor sued, but he cans till be sued for the portions belonging to others not subject to terms or conditions, because he is solidarily liable. Defense Personal to Other Debts • The defenses which are personal to one of the solidary debtors may be invoked by another solidary debtor in the event the latter is sued, but he may avail himself thereof only as regards that part of the obligation for which the debtor to whom the defense belongs is responsible. SECTION 5 Divisible and Indivisible Obligations Article 1223. The divisibility or indivisibility of the things that are the object of obligations in which there is only one debtor and only one creditor does not alter or modify the provisions of Chapter 2 of this Title. (1149) Divisible and Indivisible Obligation Divisible Obligation Is that which has for its object a thing or an act which in its delivery or performance is susceptible of division. Indivisible Obligation Is that which does not admit of division, or even though it does, neither the nature of contract nor the intention of the parties permits it to be fulfilled by parts. The basis is whether or not the obligation is susceptible of partial fulfillment according to the purpose of the said obligation. Kinds of Division 1. Qualitative – when the things separated do not form a homogeneous whole, such as an inheritance. 2. Quantitative – when a homogeneous whole is divided either by separating into parts (like in the case of movables) or by fixing their limits (like in the case of co-ownership) 3. Ideal – when the thing is not materially divided but an ideal or fractional portion is Page | 65 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 given to each person as in the case of coownership. When there is only one creditor and debtor • • The classification of obligations into divisible and indivisible does not apply when there is only one creditor and one debtor. Obligations are to be classified into divisible and indivisible only when the creditors and the debtors are several. Article 1224. A joint indivisible obligation gives rise to indemnity for damages from the time anyone of the debtors does not comply with his undertaking. The debtors who may have been ready to fulfill their promises shall not contribute to the indemnity beyond the corresponding portion of the price of the thing or of the value of the service in which the obligation consists. (1150) 1. The nature of the object. 2. The provision of law affecting the prestation 3. The will or the intention of the parties, either express or tacit. 4. The end or purpose of the obligation. Nature of Object • • • Article 1225. For the purposes of the preceding articles, obligations to give definite things and those which are not susceptible of partial performance shall be deemed to be indivisible. When the obligation has for its object the execution of a certain number of days of work, the accomplishment of work by metrical units, or analogous things which by their nature are susceptible of partial performance, it shall be divisible. However, even though the object or service may be physically divisible, an obligation is indivisible if so provided by law or intended by the parties. Exception: the obligation will be divisible only when the work is agreed to be by units of time or measure; but if the work is agreed to be by units of time or measure; but if the work is for the execution of a particular object, and the indication of the unit of time or measure is mere accidental, the obligation is indivisible. Provision of Law or Will of Parties • In obligations not to do, divisibility or indivisibility shall be determined by the character of the prestation in each particular case. (1151a) Test in Determining Divisibility or Indivisibility of Obligation The following are the factors to be considered in determining whether an obligation is divisible or indivisible: The indivisibility of the object carries with it the indivisibility of the obligation. Article 1225 provides that obligations to give definite things and those which are not susceptible of partial performance shall be deemed to be indivisible. This kind of indivisibility is referred to as natural indivisibility and may be of two kinds: o Absolute – when the nature of the object does not admit its division. In obligation to give, those for the delivery of certain objects, such as animal or a chair, are indivisible. o Relative – although the prestation is susceptible of division, it is considered an integral, indivisible amount. In obligations to do indivisibility is also presumed. • The obligation ,ay still be indivisible even when the object is divisible, by reason of the provision of law, of the express will of the parties, or of their presumed will, shown by the relation of the distinct parts of the object, each of which may be necessary complement of the others, or by the purpose of the obligation which requires the realization of all the parts. Article 1225 provides that even though the object or service may be physically divisible, an obligation is indivisible if so provided by law or intended by the parties. Page | 66 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • • These kinds of indivisibility are referred as legal and contractual indivisibility. In obligations not to do, divisibility or indivisibility shall be determined by the character of the prestation in each particular case. The indivisibility of an obligation is tested against whether it can be subject of partial performance. An obligation is indivisible when it cannot be validly performed in parts, whatever may be the nature of the thing which is the object thereof. The indivisibility refers to the prestation and not to the object thereof. SECTION 6 Obligations with a Penal Clause Article 1226. In obligations with a penal clause, the penalty shall substitute the indemnity for damages and the payment of interests in case of noncompliance, if there is no stipulation to the contrary. Nevertheless, damages shall be paid if the obligor refuses to pay the penalty or is guilty of fraud in the fulfillment of the obligation. The penalty may be enforced only when it is demandable in accordance with the provisions of this Code. (1152a) Obligations with a Penal Clause Principal and Accessory Obligations Principal Obligations Those that can stand alone independently of the existence of other obligations and have their independent and individual purpose. Accessory Obligations Those attached to a principal obligation in order to complete the same or take their place in case of breach. Penal Clause • An accessory obligation which the parties attach to a principal obligation for the • purpose of insuring the performance thereof by imposing on the debtor a special prestation (generally consisting in the payment of a sum of money) in the case the obligation is not fulfilled or is irregularly or inadequately fulfilled. An accessory undertaking to assume greater liability in case of breach. It is attached to an obligation in order to insure performance and has a double function: 1. To provide for liquidated damages 2. To strengthen the coercive force of the obligation by the threat if greater responsibility in the event of breach. Penalty and Damages • A penalty clause may be imposed essentially as penalty in case or in the nature if indemnity for damages. General Rule: the penalty shall substitute the indemnity for damages and the payment of interests in case of noncompliance, if there is no stipulation to the contrary. In the following situations, damages and interests may still be recovered on top of the penalty: 1. When there is a stipulation to that effect. 2. When the obligor having failed to comply with the principal obligation also refuses to pay the penalty, in which case the creditor is entitled to interest in the amount of the penalty, in accordance with Article 2209. 3. When the obligor is guilty of fraud in the fulfillment of the obligation. When Penal Clause Demandable In order that the penalty may be demandable, it is necessary that: 1. The total non-fulfillment of the obligation or the defective fulfillment is chargeable to the fault of the debtor. 2. That the penalty may be enforced in accordance with the provisions of law. Page | 67 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Penalty Distinguished from Condition • • • The penalty cannot be demanded when the non-fulfillment of the obligation is not imputable to the fault or negligence of the debt but to fortuitous event or due to the fault of the creditor. The burden of proof lies with the debtor. The penal clause is intended to prevent the obligor form defaulting in the performance of his obligation. When is the penalty deemed demandable in accordance with the provisions of the Civil Code? Penalty Constitutes an obligation, although accessory. May be demanded in case of nonfulfillment of the principal obligation, and even with it alone. Condition Cannot constitute an obligation. While a condition can never be demanded to be fulfilled, but whether it happens or not, only the obligation which it affects may be demanded. Positive Obligation (to give and to do) • Demandable when the debtor is in mora; hence, the necessity of demand by the debtor unless the same is excused. Negative Obligations • Demandable when the act is done contrary to that which is prohibited. When does delay arise? • Delay begins from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands form the obligor the performance of the obligation. Penalty and Liquidated Damages Lambert vs Fox • There was no difference between a penalty and liquidated damages, so far as legal results are concerned. Pamintuan vs CA • There is no justification for the Civil Code to make an apparent distinction between penalty and liquidated damages because the settled rule is that there is no difference between penalty and liquidated damages insofar as legal results are concerned and that either may be recovered without the necessity or proving actual damages and both may be reduced when proper. Article 1227. The debtor cannot exempt himself from the performance of the obligation by paying the penalty, save in the case where this right has been expressly reserved for him. Neither can the creditor demand the fulfillment of the obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time, unless this right has been clearly granted him. However, if after the creditor has decided to require the fulfillment of the obligation, the performance thereof should become impossible without his fault, the penalty may be enforced. (1153a) Right of Debtor Rule: the debtor cannot exempt himself from the performance of the principal obligation by paying the penalty. Reason: the penal clause is not a substitute for the performance of the principal obligation. Exception: the debtor may excuse himself form the performance of the principal obligation by paying the penalty if such right has been expressly reserved for him in the agreement of the penalties. • • If the agreement provides that both the principal and accessory obligations are due alternatively, and the obligation may be satisfied by the performance of one of them, the obligation becomes alternative one. If the agreement provides that it is the principal obligation which is still due after its non-fulfillment but the debtor is authorized to Page | 68 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 satisfy the obligation by paying the penalty, the obligation becomes a facultative one. Right of Creditor • In case of total non-fulfillment of the obligation, the creditor cannot, as a general rule, demand the fulfillment of the principal obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time. Exception: the creditor acquires the right to demand the fulfillment of the principal obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time if such right has been clearly granted to him. Note: the right of the creditor to demand the fulfillment of the principal obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time need not be expressly agreed upon. It is sufficient that such right has been clearly granted to him. Article 1228. Proof of actual damages suffered by the creditor is not necessary in order that the penalty may be demanded. (n) Proof of Actual Damages Not Needed • In case of breach of an obligation with a penal clause, the obligor would then be bound to pay the stipulated indemnity without the necessity of proof of the existence and the measure of damages caused by the breach. Reason: These questions and difficulties are precisely what has been sought to be avoided by the parties in stipulating the penalty. Article 1229. The judge shall equitably reduce the penalty when the principal obligation has been partly or irregularly complied with by the debtor. Even if there has been no performance, the penalty may also be reduced by the courts if it is iniquitous or unconscionable. (1154a) 1. If the principal obligation has been partly or irregularly complied. 2. Even if there has been no compliance if the penalty is iniquitous or unconscionable. • The stipulated penalty might likewise be reduced when a partial or irregular performance is made by the debtor. Laureano vs Kilayco • There is no substantial differences between a penalty and liquidated damages so far as legal results are concerned is strictly applicable only to cases wherein there has been neither partial nor irregular compliance with the terms of the contract, in which case the courts would have no authority to equitably reduce the penalty stipulated. Article 1230. The nullity of the penal clause does not carry with it that of the principal obligation. The nullity of the principal obligation carries with it that of the penal clause. (1155) Effects of Nullity of Principal Obligation or Penalty Clause • • • • The penal clause is just an accessory obligation and its existence, therefore, is merely subordinated to that of the principal obligation. The nullity of the principal obligation carries with it that of the penal clause. A principal obligation cans stand-alone independently of the existence of other obligations. The nullity of the penal clause (an accessory obligation) does carry with t that if the principal obligation. Mitigation of Penalty Courts may equitably reduce a stipulated penalty in the contract in two instances: Page | 69 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CHAPTER 4 Extinguishment of Obligations General Provisions Article 1231. Obligations are extinguished: Saura Import and Export Co. vs Development Bank of the Philippines • (1) By payment or performance; (2) By the loss of the thing due; Mutual Desistance (mutuo disenso) – derives from the principle that sicne mutual agreement can create a contract, mutual disagreement by the parties can cause its extinguishment. Other modes not mentioned in Article 1231: (3) By the condonation or remission of the debt; (4) By the confusion or merger of the rights of creditor and debtor; (5) By compensation; (6) By novation. Other causes of extinguishment of obligations, such as annulment, rescission, fulfillment of a resolutory condition, and prescription, are governed elsewhere in this Code. (1156a) Modes of Extinguishment of Obligations 1. Ipso Jure – the vinculum created by the obligation is completely broken by operation of law (Ex: payment) 2. Ope Exceptionis – the vinculum remains, but granting the debtor the right to oppose the same by exception, as in prescription. (See page 222) Stronghold Insurance Company vs Republic Asahi Glass Corp. • • • The death of either the creditor or the debtor does not extinguish the obligation and that only obligations that are personal or are identified with the persons themselves are extinguished by death. Result: will passed on to his estate. The surety cannot use the death of the bond principal to escape it monetary obligation under its performance bond. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Death Compromise Resolutory period Mutual dissent Withdrawal in certain classes of contracts by will of the parties such as in agency. 6. Change of civil status 7. Happening of an unforeseen event Section 1 – Payment or Performance Art. 1232 – Payment means not only the delivery of money but also the performance, in any other manner, of an obligation. Payment: • • • The performance of pecuniary obligations or the delivery of a sum of money. The effective performance of the agreed presentation. The performance, in any other manner, of any kind of obligation, be it an obligation to give, to do or not to do. Rules for valid payment: Arts. 1233 – 1235: essential ingredients of payment as a mode of extinguishing obligations, which is its integrity. Arts. 1236 – 1239: who may make payment. Arts. 1240 – 1243: to whom payment must be made. Arts. 1244 – 1246, 1249, and 1250: identity of the prestation or the objective element of the payment. Art. 1251: determination of proper place of payment. Art. 1247: application of expenses. Page | 70 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Note: If the rules are not strictly followed by the debtor, the creditor has a just reason in refusing to accept the payment and the consignation resorted to by the debtor shall be ineffectual. Article 1233. A debt shall not be understood to have been paid unless the thing or service in which the obligation consists has been completely delivered or rendered, as the case may be. (1157) Article 1234. If the obligation has been substantially performed in good faith, the obligor may recover as though there had been a strict and complete fulfillment, less damages suffered by the obligee. (n) Article 1235. When the obligee accepts the performance, knowing its incompleteness or irregularity, and without expressing any protest or objection, the obligation is deemed fully complied with. (n) 3. Where the different prestation are subject to different conditions or terms. Note: The mere receipt of a partial payment is not, as a rule, equivalent to the required acceptance of performance as would extinguish the whole obligation. Burden of Proof • Bank of the Philippine Islands vs Spouses Royeca: • • • Rule No. 1 Integrity of Payment Payment must be complete • • Completely means that the debtor must comply in its entirety with the prestation and that the creditor is satisfied with the same. The creditor acknowledges such full payment or proof of full payment is shown to the satisfaction of the court. Rule of Partial Payment • • The creditor cannot be compelled to accept partial payment. The creditor may not compel the debtor to make partial payment. Exceptions: 1. When there is an express stipulation to that effect 2. Where the obligation is partly liquidated and partly unliquidated, in which case, the creditor may demand that the debtor may affect the payment of the former without waiting for the liquidation of the latter. In civil cases, one who plead payment has the burden of proving it; the burden rests on the defendant to prove payment. When the creditor is in possession of the document of credit, proof of non-payment is not needed for its presumed. A promissory note in the hands of the creditor is a proof of indebtedness rather than proof of payment. An uncancelled mortgage in the possession of the mortgagee is presumed that the mortgage debt is unpaid. Guinsatao vs Court of Appeals: • Existence of the obligation can be proven by another documentary evidence such as written memorandum signed by the parties. Pacheco vs Court of Appeals • A check constitutes an evidence of indebtedness and is a veritable proof of an obligation. Note: After the debtor introduces evidence of payment, the burden of going forward with the evidence again shifts to the creditor, who then labors under a duty to produce evidence to show nonpayment. Monfort vs Aguinaldo • The receipts of payment were deemed to be the best evidence. Page | 71 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Receipt vs Voucher Receipt Voucher Written and signed A documentary acknowledgement record of a business that money has or transaction. goods has been delivered. A way or method of recording or keeping track of payments made. • benefits that the obligee expects to receive after full compliance, and the extent that the non-performance defeated the purpose of the contract. Even if the performance of the obligation is already substantial but the obligation is not fully complied with because of the debtor’s fault, the debtor may not invoke the principle of substantial performance in this article. Effect of Substantial Performance: Exception to General Rule: 1. If the obligation has been substantially performed in good faith, the obligor may recover as though there had been a strict and complete fulfillment, less damages suffered by the obligee. (Substantial Performance) 2. When the obligee accepts the performance, knowing its incompleteness or irregularity, and without expressing any protest or objection, the obligation is deemed fully complied with. (Waiver of Defect) Principle of Substantial Performance • • • • Waiver of Defect • Requisites: 1. The obligation has been substantially performed. 2. The debtor performed the obligation in good faith. What Constitutes Substantial Performance: International Hotel Corporation vs Joaquin, Jr. • • • Article 1234 applies only when an obligor admits breaching the contract after honestly and faithfully performing all the material elements thereof except for some technical aspects that cause no serious harm to the obligee. It is inappropriate when the incomplete performance constitutes a material breach of the contract. A contractual breach is material if it will adversely affect the nature of the obligation that the obligor promised to deliver, the The debtor is completely released from the obligation. He may recover as though there has been a strict and complete fulfillment. The creditor cannot require the performance of the remainder as condition sine qua non to his liability. He may recover the damages corresponding to the value of the portion which the latter failed to perform. • When the obligee accepts the performance, knowing its incompleteness or irregularity, and without expressing any protest or objection, the obligation is deemed fully complied with. To imply that creditors accept partial payment as complete performance of their obligation, their acceptance must be made under circumstances that indicate their intention to consider the performance complete and to renounce their claim arising from the defect. Article 1236. The creditor is not bound to accept payment or performance by a third person who has no interest in the fulfillment of the obligation, unless there is a stipulation to the contrary. Whoever pays for another may demand from the debtor what he has paid, except that if he paid without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, he can recover only insofar as the Page | 72 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 payment has been beneficial to the debtor. (1158a) payment depends on whether or not he has an interest in the fulfillment of the obligation. Article 1237. Whoever pays on behalf of the debtor without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, cannot compel the creditor to subrogate him in his rights, such as those arising from a mortgage, guaranty, or penalty. (1159a) Meaning of “Interest in Fulfillment of Obligation” Article 1238. Payment made by a third person who does not intend to be reimbursed by the debtor is deemed to be a donation, which requires the debtor's consent. But the payment is in any case valid as to the creditor who has accepted it. (n) Who are considered people with interest? Article 1239. In obligations to give, payment made by one who does not have the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it shall not be valid, without prejudice to the provisions of article 1427 under the Title on "Natural Obligations." (1160a) • The interest referred to must be a pecuniary or material interest in the fulfillment of the obligation and not merely social or friendly interest. 1. Guarantor and a surety – they both guarantee the fulfillment of the debtor’s obligation. 2. Accommodation mortgagors – they are liable to pay the obligation in case the debtor defaults in the payment of the obligation, although their liability extend only up to the value of their properties. 3. Person who are subsidiarily liable to pay the obligations. (ex. Employers) Land Bank of the Philippines vs Ong Rule No. 2: Who may make the payment Who may compel creditor to accept payment? • The creditor cannot be compelled to accept payment from any person. Exceptions: 1. The debtor, his heirs, assignees, or duly authorized representatives. 2. The person authorized by stipulation to make payment. 3. A third person interested in the fulfilment of the obligation. Note: If the creditor refuses to accept payment made by any of these three persons, such refusal is without just cause and entitles the debtor to resort to consignation. • The buyer of the debtor’s mortgaged is not a person interested in the fulfillment of the debtor’s obligation. Effects of Payment by Third Person • • • If the creditor accepts the payment, the same is valid, at least to the extent in which the payment may have been beneficial to the debtor, even if such payment is made by the third person without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor. Article 1236 grants the third person the right to recover from the debtor, at least up to the extent in which the payment may have been beneficial to the debtor. If the payment by a third person is beneficial to the debtor, it is clear that only the consent of the creditor is necessary in order for the payment to be valid. Interest in fulfillment of obligation • Right to Reimbursement As to whether or not a third person has the right to compel the creditor to accept his When the third person has intention to be reimbursed Page | 73 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • If the debtor’s obligation is paid by another person, the third person is generally entitled to recover from the debtor what he has paid. If the payment is made with the knowledge and consent of the debtor, the third person is entitled not only to recover what he has paid but also to be subrogated to the rights of the creditor. If the payment is made without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, the third person can only recover insofar as the payment has been beneficial to the debtor. Landbank of the Philippines vs Ong • Par. 2, Art. 1236 is applicable only if the third person made the payment on behalf of the debtor or in order to fulfill the obligation of the debtor. It does not apply when the third person made the payment for his own interest. Philippine Commercial Industrial Bank vs Court of Appeals • Accion in rem verso – remedy available to a third person in case he made the payment without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor and his payment did not redound to the debtor’s benefit, such as when the debt has been previously remitted, paid, compensated, or prescribed. In such situation, the third person has no duty to pay and the creditor has no right to receive it. When the third person has no intention to be reimbursed. • • • • The law requires the debtor’s consent because the payment is deemed to be a donation. If the debtor did not give his consent to the intention of the third person to pay his debt without being reimbursed, no donation is perfected between them. The payment made by the third person is valid as to the creditor who has accepted it. Since there is no donation if the debtor’s consent is not obtained, the third person may • • still change his mind and choose to recover from the debtor. If the debtor opposed both the donation and the payment made by the third person, the latter can recover from the former only insofar as the payment has been beneficial to the debtor. But if the debtor opposed only the donation but consented to the payment made by the third person, the third person becomes entitled to be subrogated to the rights of the creditor. Subrogation – the transfer of all the rights of the creditor to a third person, who thereby acquires all his rights against the debtor or against the third persons. Subrogation vs Reimbursement Subrogation Includes not only the right of reimbursement but, also, the rights of action against the debtor and other third persons whether they are guarantors or mortgagees. The person who pays for another acquires not only the right to be reimbursed for what he has paid but also the other rights attached to the obligation originally contracted by the debtor. Reimbursement It covers only the refund of the amount paid. The person paying for another has only a personal action to recover for what he has paid without the rights, powers and guaranties attached to the original obligation. When third person entitled to subrogation • If the third person pays the obligation without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, he is not entitled to be subrogated to the rights of the creditor. Page | 74 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • If the payment is made by a third person who has no interest in the fulfillment of the obligation, it is the consent of the debtor, not that of the creditor, which is necessary in order for the paying third person to acquire the right to be subrogated to the rights of the creditor. of the creditor. Such benefit to the creditor need not be proved in the following cases: (1) If after the payment, the third person acquires the creditor's rights; (2) If the creditor ratifies the payment to the third person; Article 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation: (3) If by the creditor's conduct, the debtor has been led to believe that the third person had authority to receive the payment. (1163a) (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor's knowledge; (2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor; (3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter's share. (1210a) Capacity to make payment • • Where the person paying has no capacity to make the payment, the creditor cannot be compelled to accept it; consignation will not be proper; in case he accepts it, the payment will not be valid. In order for the payment to be valid in obligation to give, Article 1239 of the Civil Code requires that it must be made by a person having the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it. Article 1242. Payment made in good faith to any person in possession of the credit shall release the debtor. (1164) Article 1243. Payment made to the creditor by the debtor after the latter has been judicially ordered to retain the debt shall not be valid. (1165) Rule No. 3 To whom must payment to be made Proper Person to receive payment 1. The person in whose favor the obligation has been constituted. 2. His successor in interest. 3. Any person authorized to receive it. A person authorized to receive it • Article 1240. Payment shall be made to the person in whose favor the obligation has been constituted, or his successor in interest, or any person authorized to receive it. (1162a) Article 1241. Payment to a person who is incapacitated to administer his property shall be valid if he has kept the thing delivered, or insofar as the payment has been beneficial to him. Payment made to a third person shall also be valid insofar as it has redounded to the benefit Means not only a person authorized by the same creditor, but also a person authorized by law to do so, such as guardian, executor or administrator of estate of a deceased, and assignee or liquidator of a partnership or corporation, as well as any other who may be authorized to do so by law. Effect of payment to wrong person, General rule. • • It does not extinguish the obligation as to the creditor, if there is no fault or negligence which can be imputed tot the latter. Such payment does not prejudice the creditor nor deprive him of his right to demand payment. Page | 75 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • If it becomes impossible to recover what was duly paid, any loss resulting therefrom shall be borne by the deceived debtor. Exceptions to Rule: When payment to wrong party considered valid A. When payment redounds to creditor’s benefit. Burden of proving benefit to creditor: • • He was the one who committed the mistake of paying a wrong party. He has the burden of proving that his obligation had been extinguished. The debtor no longer has the duty to prove the benefit to the creditor because the law itself presumes the existence of such benefit: (1) If after the payment, the third person acquires the creditor's rights; (2) If the creditor ratifies the payment to the third person; (3) If by the creditor's conduct, the debtor has been led to believe that the third person had authority to receive the payment. B. Payment to Possessor of Credit in Good Faith. Example: A debtor pays possessor of credit i.e., someone who is not the real creditor but appears, under the circumstances, to be the real creditor. The law considers the payment to the possessor of credit as valid even as against the real creditor taking into account the good faith of the debtor. • The payment must be made to a wrong person and not someone entitled to the payment, otherwise the provision will no longer require good faith on the part of the payor. If the promissory note executed by the debtor is payable to “X” and the latter assigned his credit to “Y” is a valid payment under Article 1240 of the Civil Code and not under Article 1242, because “Y” is a successor-in-interest of the original creditor. If the promissory note, on the other hand, is payable to the order of “X” and “X” validly negotiated the instrument to “Y” through endorsement and delivery, “Y” also becomes a successor-in-interest entitled to the payment. • If the promissory note executed by the debtor in favor of his creditor is “payable to bearer,” the possession of the instruments is possession of the credit itself. C. Payment in Good Faith to Assignor of Credit Assignment of Credit – An agreement by virtue of which the owner of the credit by a legal cause – such as sale, dation in payment or exchange or donation – and without need of the debtor’s consent, transfers that credit and its accessory rights to another who acquires the power to enforce it, to the same extent as the assignor could have enforced it against the debtor. Purpose: if creditor acts in bad faith in assigning another person to receive payment, the debtor (having no knowledge of such assignment) pays the creditor, he shall be released from his obligation • • The debtor’s consent is not essential for the validity of the assignment. What the law requires in an assignment of credit is not the consent of the debtor but merely notice to him. Capacity of Payee If the payment is made to a person incapacitated to administer his property, the payment is invalid except in the following situations: 1. If he has kept the thing delivered. 2. If the payment has been beneficial to him. Example: Page | 76 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Effect of Court to Retain Debt • Payment made to the creditor after the latter has been judicially ordered to retain the debt should not be valid. “After the latter has been judicially ordered” • Refers to the date of receipt of the notice of such judicial order and not on the date of its issuance. Article 1244. The debtor of a thing cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be of the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due. In obligations to do or not to do, an act or forbearance cannot be substituted by another act or forbearance against the obligee's will. (1166a) Article 1245. Dation in payment, whereby property is alienated to the creditor in satisfaction of a debt in money, shall be governed by the law of sales. (n) Article 1246. When the obligation consists in the delivery of an indeterminate or generic thing, whose quality and circumstances have not been stated, the creditor cannot demand a thing of superior quality. Neither can the debtor deliver a thing of inferior quality. The purpose of the obligation and other circumstances shall be taken into consideration. (1167a) Article 1247. Unless it is otherwise stipulated, the extrajudicial expenses required by the payment shall be for the account of the debtor. With regard to judicial costs, the Rules of Court shall govern. (1168a) Article 1248. Unless there is an express stipulation to that effect, the creditor cannot be compelled partially to receive the prestations in which the obligation consists. Neither may the debtor be required to make partial payments. However, when the debt is in part liquidated and in part unliquidated, the creditor may demand and the debtor may effect the payment of the former without waiting for the liquidation of the latter. (1169a) Article 1249. The payment of debts in money shall be made in the currency stipulated, and if it is not possible to deliver such currency, then in the currency which is legal tender in the Philippines. The delivery of promissory notes payable to order, or bills of exchange or other mercantile documents shall produce the effect of payment only when they have been cashed, or when through the fault of the creditor they have been impaired. In the meantime, the action derived from the original obligation shall be held in the abeyance. (1170) Article 1250. In case an extraordinary inflation or deflation of the currency stipulated should supervene, the value of the currency at the time of the establishment of the obligation shall be the basis of payment, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. (n) Rule No. 4: Identity of Prestation • The very due must be delivered or released. What must be paid A. In Determinate Obligation • The debtor cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be of the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due. B. In Indeterminate Obligation • The obligation can be complied with by the delivery of a thing belonging the said genus but the following rules must be observed: 1. The delivery must be in accordance with the quality and circumstances agreed upon. 2. In the absence of such agreement, the creditor cannot demand a thing of Page | 77 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 superior quality and neither can the debtor deliver a thing of inferior quality. C. In Personal Obligation • In obligation to do or not to do, an act or forbearance cannot be substituted by another act or forbearance against the creditor’s will. 2. P 100 for denominations of 1-sentimo, 5sentimo, 10-sentimo, and 25-sentimo. Checks are not legal tender • Payment of Debts in Money Rules if the obligation is to pay a sum of money: 1. The payment shall be made in the currency stipulated. 2. If it is not possible to deliver the currency stipulated or in the absence of such stipulation, the payment must be in the currency which is legal tender in the Philippines. • • A check whether a manager’s check or ordinary check, is not legal tender, and an offer of a check in payment of a debt is not a valid tender of payment and may be refused by the obligee or creditor. Applicable only to payment of an obligation. Inapplicable to the exercise of a right. Fortunado vs Court of Appeals • • Stipulation for Payment in Foreign Currency Check may be used for the exercise of the right of redemption, the same being a right and not an obligation. The tender of a check is sufficient to compel redemption but is not in itself a payment that relieves the redemptioner from his liability to pay the redemption price. Before: Any agreement to pay an obligation in a currency other than the Philippine currency is void; the most that could be demanded is to pay said obligation in Philippine Currency to be measured in the prevailing rate of exchange at the time the obligation was incurred. Article 1249 is applicable if: Now: In case of foreign borrowings and foreign currency loans, however, prior Bangko Sentral approval was required. The same statute also explicitly provided that parties may agree that the obligation or transaction shall be settled in a currency other than the Philippine currency at the time of payment. Article 1249 is not applicable if: Currency which is legal tender in the Philippines If creditor accepts Check as Payment Legal Tender Coins issued by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas have limited legal tender power. The maximum amount of coins to be considered as legal tender shall be as follows: 1. P 1,000 for denominations of 1-Piso, 5-Piso, and 10-Piso coins. • • • The payment of the price can be demanded as a legal obligation, the tender of check is precisely for the purpose of extinguishing an obligation. There is no legal obligation to pay the price because the payor may choose not to pay if he decides not to exercise his right, i.e., right of redemption. He is estopped from later on denouncing the efficacy of such tender of payment. A check and similar instruments operate as payment only when: 1. They have been encashed. 2. They have been impaired through the fault of the creditor. Page | 78 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 BPI vs Spouses Royeca • The obligation to prove that the checks were not dishonored, but were in fact encashed, fell upon the debtors who would beneft from such fact. Papa vs A.U. Valencia and Co., Inc. • • Even if the creditor had never encashed the check, his failure to do so for more than 10 years undoubtedly resulted in the impairment of the check through his unreasonable and unexplained delay. It will be held to operate as actual payment of the debt or obligation for which it was given. Extraordinary Inflation and Deflation Effect of Extraordinary Inflation or Deflation. • The value of the currency at the time of the establishment of the obligation shall be the basis of the payment. Requisites for Application of Article 1250 1. That there was an official declaration of extraordinary inflation and deflation from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. 2. That the obligation was contractual in nature. 3. That the parties expressly agreed to consider the effects of the extraordinary inflation or deflation. • • Dation in Payment (Dacion en Pago) • • Exception: • It is inly when there is an agreement to the contrary that the extraordinary inflation will make the value of the currency at the time of payment, not at the time of the establishment of the obligation, the basis for payment. What Constitutes Extraordinary Inflation or Deflation Where the obligation to pay arises from law and not from contractual obligation, such as in the taking of private property by Government in the exercise of its power of eminent domain, Article 1250 of the Civil Code does not apply. The provision is also inapplicable to the obligations arising from tort. The alienation of property to the creditor in satisfaction of a debt in money. The debtor delivers and transmits to the creditor the former’s ownership over a thing as an accepted equivalent of the payment or performance of an outstanding debt. Dation in Payment vs Objective Novation • What actually takes place in decion en pago is an alternative novation of the obligation where the thing offered as an accepted equivalent of the performance of an obligation is considered as the object of the contract of the sale, while the debt is considered as the purchase price. Inflation – The sharp increase of money or credit, or both, without a corresponding increase in business transaction. • When there is an increase in the volume of money and credit relative to available goods, resulting in a substantial and continuing rise in the general price level. Mode of extinguishment Dation in Payment The original obligation of the debtor must be to pay a sum in money. Objective Novation The debt is not in money and the creditor accepts the delivery of the property of the performance Page | 79 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 The equivalent of the payment of an outstanding debt must be the alienation of a property. of the obligation. The equivalent of the performance of the obligation is not the alienation of property but some other prestation. Requisites for valid decion en pago Extent of Extinguishment of Debt • CESSION • Rockville Excel International Exim Corp vs Culla 1. Existence of a money obligation 2. The alienation to the creditor of a property by the debtor with the consent of the former 3. Satisfaction of the money obligation of the debtor. In other cases: 1. There must be the performance of the prestation in lieu of payment which may consist in the delivery of a corporeal thing or a real right or a credit against the third person. 2. There must be some difference between the prestation due and that which is given in substitution. 3. There must be an agreement between the creditor and debtor that the obligation is immediately extinguishing by reason of the performance of a prestation different from that due. Property • Need not be corporeal thing but may also include a real right or a credit against a third person. Note: if the alienation of property is by ay of security, and not by way of satisfying the debt, there is no decion en pago. Dation in payment extinguishes the obligation to the extent of the thing delivered, either as agreed upon by the parties or as may be proved, unless the parties by agreement – express or implied, or by their silence – consider the thing as equivalent to the obligation, in which case the obligation is totally extinguished. • Payment by cession contemplates of a situation where the debtor is indebted to several creditors but he is under the state of insolvency, or that the debtor is generally unable to pay his liabilities as they fall due in the ordinary course of business or has liabilities that are greater than his assets. The debtor abandons all his properties or assets to his creditors so that the latter may sell the same and apply the proceeds to the satisfaction of their credits. Cession vs Dacion En Pago Cession Dacion En Pago Requires plurality of Number of creditors creditors is immaterial in dacion. Involves the Involves specific universality or the property or whole of the properties of the property of the debtor debtor The debtor is under The debtor is under the state of the state of financial insolvency difficulties because if the debtor is insolvent, he is generally prohibited from resorting to dacion en pago as it would give undue preferenc to a creditor. The creditors do not Involves the acquire ownership delivery and over the properties transmission of Page | 80 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 of the debtor because the transfer of possession to them is only for the purpose of the sale of properties. Payment by cession releases the debtor from responsibility only up to the extent of the net proceeds of the sale. ownership of thing as an accepted equivalent of the performance of the obligation. Extinguishes the obligation to the extent of the value of the things delivered, either as agreed upon by the parties or as may be proved, unless the parties by agreement, express or implied, or by their silence, consider the thing as equivalent to the obligation, in which case, the obligation is totally extinguished. Expenses Required by Payment A. Extrajudicial Expenses To who shall bear extrajudicial expenses? 1. The parties may freely stipulate as to who shall bear said expenses. 2. In the absence of the stipulations, said expenses shall be for the account of the debtor. B. Judicial Expenses • • If the expenses required by the payment are no longer connected with, or arising from, the normal fulfillment of the obligation, but as a consequence of the judicial proceeding, they are referred to as judicial expenses. As to judicial expenses or costs, the same shall be governed by the Rules of Court. Article 1251. Payment shall be made in the place designated in the obligation. There being no express stipulation and if the undertaking is to deliver a determinate thing, the payment shall be made wherever the thing might be at the moment the obligation was constituted. In any other case the place of payment shall be the domicile of the debtor. If the debtor changes his domicile in bad faith or after he has incurred in delay, the additional expenses shall be borne by him. These provisions are without prejudice to venue under the Rules of Court. (1171a) Rule No. 5: Proper Place of Payment • The creditor cannot be compelled to accept the payment if the same is made in a place other than the proper place of payment. Rules in determining proper place of payment: 1. If the place of payment is designated in the obligation, the payment shall be made in the said place. 2. In the absence of stipulation and the obligation is to deliver a determinate thing, the payment shall be made in the place where the thing might be at the time of the constitution of the obligation. 3. In any other cases, the place shall be the domicile of the debtor. • • Whether the change in the domicile is done in good faith or in bad faith, the place of payment shall still be the debtor’s new domicile. If he debtor changes his domicile in bad faith or after he was incurred in delay, the additional expenses that the creditor may incur in going to the debtor’s new domicile shall be borne by the debtor. Page | 81 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 SUBSECTION 1. Application of Payments Article 1252. He who has various debts of the same kind in favor of one and the same creditor, may declare at the time of making the payment, to which of them the same must be applied. Unless the parties so stipulate, or when the application of payment is made by the party for whose benefit the term has been constituted, application shall not be made as to debts which are not yet due. If the debtor accepts from the creditor a receipt in which an application of the payment is made, the former cannot complain of the same, unless there is a cause for invalidating the contract. (1172a) Application of Payments Application of payment is applicable only to debts which are already due. Exceptions: 1. When there is a stipulation allowing such application. 2. When the application is made by the party for whose benefit the term has been constituted. Who has right to make application of payment? A. Right Initially to Debtor Special forms of payment under the Civil Code: 1. 2. 3. 4. both contingent and singular; his liability is confined to such obligation, and he is entitled to have all payments made applied exclusively to said application and to no other. Dation in Payment (Art. 1245) Payment by cession (Art. 1255) Application of payments (Arts. 1252-1254) Tender of payment and consignation (Arts. 1256-1261) Basis: First sentence of Article 1252 of the Civil Code. B. Debtor Rights is not Mandatory • The debtor’s right to apply payment has been considered merely directory, and not mandatory. Article 1252 gives right to the debtor to choose to which several obligations to apply a particular payment that he tenders to the creditor. Granted in the same provision is the right of the creditor to apply such payment in case the debtor fails to direct its application. and • Application of Payment – the designation of the debt to which should be applied the payment made by a debtor who owes several debts to the same creditor. • Requisites: C. Creditor may propose application Concept of Requisites: Application of Payments 1. There be several debts. 2. Those debts are owed by one debtor to one creditor. 3. All debts must be of the same kind. 4. All debts must be due. 5. The payment made is not sufficient to cover all debts. • This concept applies only to a “person owing several debts of the same kind of a single creditor,” it cannot be made applicable to a person whose obligation as a mere surety is • • • The debtor is required to make the application at the time of the payment. Should the debtor fail to exercise such right at the time of the payment, the same is extinguished. Thereafter, the creditor acquires the right to propose an application of payment by issuing receipt in which an application of payment is made, which proposal does not bind the debtor unless he accepts the same. Page | 82 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Where the debtor has not expressly elected any particular obligation to which the payment should be applied, the application by the creditor, in order to be valid and lawful, depends: 1. Upon his expressing such application in the corresponding receipt. 2. Upon the debtor’s assent, shown by his acceptance of the receipt without protest. D. Limitations upon right to apply payment 1. The debtor cannot make an application of payment that will violate the agreement. 2. The debtor cannot make an application of payment that will violate the rule in Article 1248 of the Civil Code. 3. The debtor cannot make an application of payment in violation of the rule in Article 1253 of the Civil Code. Relevant on questions pertaining to the effects and nature of the obligations in general. The presumption does not resolve the question of whether the amount received by the creditor is a payment for the principal or interest. The amount received by the creditor is the payment for the principal. Article 1253. If the debt produces interest, payment of the principal shall not be deemed to have been made until the interests have been covered. (1173) Presumption on Payment of Interest A. When debt produces interest The rule in this article that payments shall first be applied to the interest and not to the principal shall govern if two facts exists: 1. The debt produces interest 2. The principal remains unpaid B. Kinds of Interest 1. Stipulated monetary interest 2. Interest for default (compensatory) C. Article 1176, in relation to Article 1253, Civil Code Article 1176 Article 1253 Chapter 1 (Nature Subsection 1 and Effect of (Application of Obligation) Payments) Chapter Resolves the doubt by presuming that the creditor waives the payment of interest because he accepts payment for the principal without any reservation. IV (Extinguishment of Obligations) Pertinent on questions involving application of payments and extinguishment of obligations. The presumption resolves doubts involving payment of interest-bearing debts. The doubt pertains to the application of payment; the uncertainty is on whether the amount received by the creditor is payment for the principal or the interest. Resolves the doubt by providing a hierarchy: payment first be applied to the interest; payment shall the be applied to the principal only after the interest has been fully-paid. Note: When the doubt pertains to the application of the payments, Article 1253 shall apply. Only when there is a waiver of interest shall Article 1176 become relevant. Swagman Hotels and Travel Inc. vs Court of Appeals The creditors were deemed to have waived the payment of interest because they issued receipts expressly referring to the payment of the principal without any reservation with respect to the interest. As a result, the interests due were deemed waived. Page | 83 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1254. When the payment cannot be applied in accordance with the preceding rules, or if application cannot be inferred from other circumstances, the debt which is most onerous to the debtor, among those due, shall be deemed to have been satisfied. If the debts due are of the same nature and burden, the payment shall be applied to all of them proportionately. (1174a) Application of Payment by Operation of Law A. When no application was made by parties In the absence of express application by the debtor, or of any receipt issued by the creditor specifying a particular imputation of the payment: 1. The debt which is more onerous to the debtor, among those due, shall be deemed to have been satisfied. 2. If the debts due are of the same nature and burden, the payment should be applied to all of them proportionately. B. Debt more onerous to debtor 1. Debts covered by guaranty are deemed more onerous to the debtor than the simple obligations. 2. When a person has two debts, one as sole debtor and another as solidary co-debtor his more onerous obligation to which first payments are to be applied is the debt as sole debt. 3. Where there are various debts, the oldest ones are more burdensome, and payments should be applied to them before the more recent ones. 4. Where one debt bears interest and the other does not, even if the latter should be the older generation, the former is considered as more onerous. Where both debts bear interest, the one with the higher rate is more burdensome. 5. Debts with a penal clause are more onerous than those without one. 6. Where the debtor had entered into various contracts with the creditor, including a lease contract over a wet-market property where he invested P35 Million and sale of 8 heavy equipment, the lease over the wet market is more onerous among all obligations because the wet market is a going concern and the debtor would stand to lose more if the lease would be rescinded, than if the contract of sale of heavy equipment would not proceed. SUBSECTION 2. Payment by Cession Article 1255. The debtor may cede or assign his property to his creditors in payment of his debts. This cession, unless there is stipulation to the contrary, shall only release the debtor from responsibility for the net proceeds of the thing assigned. The agreements which, on the effect of the cession, are made between the debtor and his creditors shall be governed by special laws. (1175a) (See notes on Cession) SUBSECTION Consignation 3. Tender of Payment and Article 1256. If the creditor to whom tender of payment has been made refuses without just cause to accept it, the debtor shall be released from responsibility by the consignation of the thing or sum due. Consignation alone shall produce the same effect in the following cases: (1) When the creditor is absent or unknown, or does not appear at the place of payment; (2) When he is incapacitated to receive the payment at the time it is due; (3) When, without just cause, he refuses to give a receipt; (4) When two or more persons claim the same right to collect; (5) When the title of the obligation has been lost. (1176a) Page | 84 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Tender of Payment and Consignation Effect of Non-Acceptance of Payment • • • • The creditor’s unjust refusal to accept payment does not produce the effect of payment that will extinguish the debtor’s obligation. A refusal without just cause is not equivalent to payment. To have the effect of payment and the consequent extinguishment of the obligation to pay, the law requires the companion acts of tender of payment and consignation. Tender of payment produces no effect; rather, tender of payment must be followed by a valid consignation in order to produce the effect of payment and extinguish an obligation. State Investment House Inc. vs Court of Appeals • • • The debtor is exempt from paying compensatory interest only but he remains liable to pay the monetary interest. If the tender of payment is valid and the creditor refuses to accept the payment, the debtor is not guilty of delay. With respect to monetary interest, the same accrues until actual payment of the principal amount is effected. Llamas vs Abaya • A written tender of payment alone, without consignation in court of the sum due, does not suspend the accruing of regular or monetary interest. Bonrostro vs Luna Where the creditor unjustly refuses to accept payment, the debtor desirous of being released from his obligation must comply with two conditions: 1. Tender of payment 2. Consignation of the sum due. • The debtors are liable for interest on the installments due from the date of default until fully paid. • With respect to the accrual of the regular or monetary interest until actual payment of the principal amount is effected notwithstanding the existence of a valid tender of payment, applies only when the tender of payment is not followed by a valid consignation. • When the tender of payment is coupled with consignation, such that the thing is deposited in court or placed at the disposal of the judicial authority, justice and equity demands that the debtor be freed from obligations to pay interest on the outstanding amount from the time the unjust refusal took place since he would not have been liable for any interest from the time tender of payment was made if the payment had only been accepted. What is the effect of a valid tender of payment which the creditors refuse to accept? PNB vs Relativo • The effect of a valid tender of payment is merely to exempt the debtor from payment of interest and/or damages. Two kinds of interest: 1. Monetary Interest – the compensation set by the parties for the use or forbearance of money. 2. Compensatory Interest – the penalty or indemnity for damages imposed by law or by the courts. Is the debtor exempt from paying both kinds of interest by reason of his valid tender of payment? Biesterbos vs Court of Appeals • Equity and justice would demand that such an act, placing at the disposal of respondent (creditor) the deposited sum, should have the effect of suspending the running of the interest on said outstanding amount. Page | 85 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Tender of Payment • • • • The definitive act of offering the creditor what is due him or her, together with the demand that the creditor accepts the same. For valid tender of payment, it is necessary that there be a fusion of intent, ability and capability to make good such offer, which must be absolute and must cover the amount due. Mere sending of letter by the vendee expressing the intention to pay without the accompanying payment was not considered a valid tender of payment. Tender of payment presupposes not only that the obligor is able, ready, and willing, but more so, in the act of performing his obligation. Ab posse ad actu non vale illatio • A proof that an act could have been done is no proof that it was actually done. Consignation • • The remedy for an unjust refusal to accept was actually done. The act of depositing the thing due with the court or judicial authorities whenever the creditor cannot accept or refuses to accept payment and it generally requires a prior tender of payment. Rationale: to avoid the performance of an obligation becoming more onerous to the debtor by reason of causes not imputable to him. Tender of Payment vs Consignation • • • Tender is the antecedent of consignation An act preparatory to the consignation, which is the principal, and from which are derived the immediate consequences which the debtor desires or seeks to obtain. Tender of payment may be extrajudicial, while consignation is necessarily judicial. • The priority of tender or payment is to attempt to make a private settlement before proceeding to the solemnities of consignation. Note: Tender and consignation, where validly made, produces the effect of payment and extinguishes the obligation. Article 1257. In order that the consignation of the thing due may release the obligor, it must first be announced to the persons interested in the fulfillment of the obligation. The consignation shall be ineffectual if it is not made strictly in consonance with the provisions which regulate payment. (1177) Article 1258. Consignation shall be made by depositing the things due at the disposal of judicial authority, before whom the tender of payment shall be proved, in a proper case, and the announcement of the consignation in other cases. The consignation having been made, the interested parties shall also be notified thereof. (1178) Requisites for valid consignation: 1. There was a debt due 2. The consignation of the obligation has been made because the creditor to whom the tender of payment was made refused to accept it, or because he was absent, or because several persons claimed to be entitled to receive the amount due or because the title of the obligation has been lost. 3. Previous notice of the consignation has been given to the person interested in the performance of the obligation. 4. After the consignation has been made, the person interested was notified thereof. Note: Failure in any of these requirements is enough to render a consignation ineffective. Page | 86 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Compliance with the requisites mandatory Soco vs Militante: • • • Failure to comply strictly with any of the requirements will render the consignation void. The essential requisites of a valid consignation must be complied with fully and strictly in accordance with the law. Substantial compliance is not enough. Requisite No. 1: There must be a debt due • • Where no debt is due and owing, consignation is not proper. Consignation is not required to preserve the right of repurchase as a mere tender of payment is enough is made on time as a basis for an action to compel the vendee a retro to resell the property. Consignation in Article 1256 • • • • Refers to consignation as one of the means for the payment or discharge of a “debt”. It does not apply when the lessee merely exercised the option to buy the leased premises because here the lessee was not indebted to the lessor for the price of the leased premises. Consignation is likewise not required in order to preserve the right to redeem because the right to redeem is a right, not an obligation. In cases which involve the performance of an obligation and not merely the exercise of a privilege or right, payment maybe effected not by mere tender alone but by both tender and consignation. Requisite No. 2: Unjust Refusal to Accept Generally, requires prior valid tender of payment • In the absence of a valid prior tender of payment, the consignation is invalid. 1. When the creditor is absent or unknown, or does not appear at the place of payment; 2. When he is incapacitated to receive the payment at the time it is due; 3. When, without just cause, he refuses to give a receipt; 4. When two or more persons claim the same right to collect; 5. When the title of the obligation has been lost. (Article 1256) Example: Pasricha vs Don Luis Dison Realty, Inc. • • The lessees failed to pay the rentals because they did not know to whom payment should be made The Court held that such failure to pay was not justified because the lessees could have availed of the remedy of consignation. Refusal to accept payment is without just cause • • • For a consignation to be necessary, the creditor must have refused, without just cause, to accept the debtor’s payment. If the payment was accepted by the creditor, there is no need for consignation. If a creditor refuses with reason to accept a tender of payment made by the debtor and the former makes a consignation of the thing due, the debtor will not be relived from his liability by the consignation and the loss or deterioration in value of the thing due or deposited shall be borne by the debtor. Example: A creditor may refuse to accept the tender of payment if the tender is made before the obligation of the debtor becomes due, or the thing rendered is different in specie or amount from what is due, or the obligation is not payable at the time the tender of payment was made. When is the creditor justified in refusing to accept the tender of payment? Instances where prior tender of payment is excused: Page | 87 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • If the tender of payment made by the debtor is not valid, the creditor has just cause for refusing to accept the same. Requisite Nos. 3 and 5: Two Notices Required 1. To be given prior to the deposit of the payment in court (or prior to consignation) 2. To be issued after the deposit has been made (or after the consignation) Requirement of Prior Notice Purpose: In order to give the creditor an opportunity to reconsider his unjustified refusal and to accept payment thereby avoiding consignation and the subsequent litigation. • The prior notice requirement is held to be satisfied when the debtor informed the creditor in a letter that should the latter fail to accept payment, the former would consign the amount. Article 1259. The expenses of consignation, when properly made, shall be charged against the creditor. (1179) Article 1260. Once the consignation has been duly made, the debtor may ask the judge to order the cancellation of the obligation. Before the creditor has accepted the consignation, or before a judicial declaration that the consignation has been properly made, the debtor may withdraw the thing or the sum deposited, allowing the obligation to remain in force. (1180) Article 1261. If, the consignation having been made, the creditor should authorize the debtor to withdraw the same, he shall lose every preference which he may have over the thing. The co-debtors, guarantors and sureties shall be released. (1181a) Effects of Consignation Past Notice Requirement Right of Debtor to Withdraw Deposit Purpose: To enable the creditor to withdraw the goods or money deposited. It would be unjust to make him suffer the risk of any deterioration, depreciation or loss of such goods or money by reason of ack of knowledge of the consignation. The debtor may withdraw the thing or amount deposited on consignation in the following instances: All interested Persons Must Be Notified • Failure to notify the persons interested in the performance of the obligation will render the consignation void. 1. Before the creditor has accepted the consignation 2. Before a judicial declaration that the consignation has been properly made. • Requisite No. 4: Deposit of Payment in Court • • • Consignation shall be made by depositing the thing or things due at the disposal of judicial authority. It clearly precludes consignation in venues other than the courts. Elsewhere, what may be made is a valid tender of payment, but not consignation. • • After the creditor has accepted the consignation or after the court has declared the consignation to be properly made, the debtor can no longer withdraw the thing or amount deposited without the authorization of the creditor. After the creditor has accepted the consignation or after the court has declared the consignation to be properly declared, the debtor may not be allowed to withdraw the thing or amount deposited if he authorized by the creditor. Such authorization does not result in the extinguishment of the debtor’s obligation because the obligation has not yet been paid but the co-debtors, guarantors and sureties Page | 88 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 are considered released from the obligation. The creditor will likewise lose his right over the thing deposited. • Right of Creditor to Withdraw Deposit • Upon being notified that the consignation has been made, the creditor may choose to accept the same unconditionally and without reservations, in which case the obligation is considered extinguished and such acceptance will prevent the debtor from withdrawing the thing or amount deposited. May the creditor be allowed to withdraw the amount deposited with reservation as to the validity of the consignation? • • • The Court ruled that the same is legally permissible and does not result in the waiver of the claims which the creditor reserved against his debtor. Sensu Contrario – when the creditor’s acceptance of the money consigned is conditional and with reservations, he is not deemed to have waived the claims he reserved against his debtor. As respondent-creditor’s acceptance of the amount consigned was with reservations, it did not completely extinguish the entire indebtedness of the petitioner-debtor. Retroactive Effect of Consignation • The consignation has a retroactive effect, and the payment is deemed to have been made at the time of the deposit of the thing in court or when it was placed at the disposal of the judicial authority. Rationale: to avoid making the performance of an obligation more onerous to the debtor by reason of causes not imputable to him. Expenses of Consignation • The same shall be charged against the creditor when the consignation is properly made, such as when the creditor accepts the same without objections, or, if he objects, the court declares that it has been validly made in accordance with law. If the consignation is declared invalid, such expenses shall be for the account of the debtor. SECTION 2 Loss of the Thing Due Article 1262. An obligation which consists in the delivery of a determinate thing shall be extinguished if it should be lost or destroyed without the fault of the debtor, and before he has incurred in delay. When by law or stipulation, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous events, the loss of the thing does not extinguish the obligation, and he shall be responsible for damages. The same rule applies when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. (1182a) Article 1263. In an obligation to deliver a generic thing, the loss or destruction of anything of the same kind does not extinguish the obligation. (n) Article 1264. The courts shall determine whether, under the circumstances, the partial loss of the object of the obligation is so important as to extinguish the obligation. (n) Article 1265. Whenever the thing is lost in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the loss was due to his fault, unless there is proof to the contrary, and without prejudice to the provisions of article 1165. This presumption does not apply in case of earthquake, flood, storm, or other natural calamity. (1183a) Concept of Loss as Mode of Extinguishment of Obligation • • This mode of extinguishment is not limited to obligations to give. It also covers obligations to do or not to do. Concept of Loss in Obligations to Give • This mode of extinguishment is applicable only to obligations to deliver a determinate Page | 89 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 thing and does not apply to obligations to deliver a generic thing. Rule in Determinate Obligation Definition of Loss Basis: the genus of a thing can never be perished (Genus nunquan perit) • Determinate thing vs Generic thing Determinate Thing When it is particularly designated or physically segregated from all others of the same class. Generic Thing When it is designated merely by its class or genus without any particular designation or physical segregation from all others of the same class. A concrete, Its determination is particularized confined to that of object, indicated by its nature, to the its own individuality. genus (genero) to which it pertains, such as a horse, a chair. The thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered, Article 1189 (2). “perishes” – when it dies, in the case of animate objects; when it rots in the case of perishable objects. “goes out of commerce” – when its possession has become unlawful, as when it has been used as an instrument in the commission of the crime, or it can no longer be the object of contracts, as where the land which is the subject matter of the obligation to give has been expropriated for public use. “disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown” – as when, for example, in the case of a wild animal, it has escaped and regained its freedom and cannot be found. “cannot be recovered” – when for instance in the case of a ship, it sunk in the middle of the sea. Rule in Generic Obligations • • • • In an obligation to deliver a generic thing, the loss or destruction of anything of the same kind does not extinguished the obligation. The loss or destruction of anything of the same kind even without the debtor’s fault and before he incurred in delay will not have the effect of extinguishing the obligation. Basis: Genus nunquan perit Example: Where the obligation consists in the payment of money, the failure of the debtor to make the payment even by reason of a fortuitous event shall not relieve him of his liability. Reason: This is because an obligation to pay money is generic; therefore, it is not excused by fortuitous loss of any specific property of the debtor. In Article 1262, the loss of the determinate thing subject matter of the obligation to give necessarily occurs after the constitution of the obligation because the law speaks of extinguishment of the obligation as a consequence. Effects of Loss of Determinate Thing Due Requisites in order that the loss will extinguish the obligation and exempt the obligor from any further liability: 1. The lost occurs without the fault of the debtor. 2. The loss occurs prior to the debtor incurring the delay. 3. There is no law or stipulation holding the debtor liable even in the case of fortuitous event, or that the nature of the obligation does not require the assumption of risk. Page | 90 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 If the foregoing requisites are not present, the debtor’s obligation to deliver a determinate thing is not considered extinguished. Instead, the obligation is converted into payment of damages. • • In order for the obligation to extinguished by reason of the loss of the determinate thing, what is essential is that the loss be without the fault of the debtor. To be exempt from liability by reason of fortuitous event, it is also essential that the debtor must be free from any participation in, or aggravation of the injury to the creditor. The debtor shall remain liable even if the loss is by reason of fortuitous event in the following instances: 1. When the law expressly provides for liability even for fortuitous event. 2. When the stipulation of the parties expressly provides for liability for fortuitous event. 3. When the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. Example: One of said instances is when the debtor delays or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest. Applicability Obligations of the Rule to Reciprocal Where both parties are obligated (reciprocally or not) and the obligation of one is extinguished by fortuitous event, does the other party remain bound or is he released? Ans: The extinguishment of the obligation due to loss of the thing or impossibility of performance effects both the debtor and creditor; the entire juridical relation is extinguished, so that if the creditor has himself an obligation, this is likewise extinguished. Chrysler Philippine Corporation vs Court of Appeals • The Court held that before delivery, the risk of loss is borne by the seller who is still the owner, under the principle of res perit domino. Effects of Partial Loss • The loss is due to the debtor’s fault when the determinate thing due is lost in his possession. Reason: Since he who has the custody and care of the thing can easily explain the circumstances of the loss. The presumption does not apply in the following instances: 1. When there is proof to the contrary. 2. When the loss occurs during an earthquake, flood, storm or other natural calamity. Example: When the owner left his vehicle in a repair shop and the same was allegedly carnapped while in the possession of the repair shop, the owner of the repair shop was held liable for such loss because he failed to rebut the presumption and since the case does not fall under the exceptions. (Co vs Ca) Article 1266. The debtor in obligations to do shall also be released when the prestation becomes legally or physically impossible without the fault of the obligor. (1184a) Article 1267. When the service has become so difficult as to be manifestly beyond the contemplation of the parties, the obligor may also be released therefrom, in whole or in part. (n) Basis: principle of res perit domino – the risk pertains to the debtor, which means that if an obligation is extinguished by the loss of the thing or impossibility of performance through fortuitous events, the counter-prestation is also extinguished. Page | 91 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Concept of Loss in Obligations to Do • Impossibility of Performance • The article is applicable to obligations “to do”, and not to obligations “to give.” • Obligation to do – includes all kinds of work or service. Obligation to give – a prestation which consists in the delivery of a movable or an immovable thing in order to create a real right, or for the use of the recipient, or for its simple possession, or in order to return it to its owner. • • The impossibility referred to is either a physical or legal impossibility. Physical Impossibility • • When the act by reason of its nature cannot be accomplished. May also proceed principally from the death of the obligor, in obligations of a most personal character to him, and in those which have a similar character in respect to the creditor, for having to be done for his exclusive benefit, when it is he who dies, since in the former and in the latter case the obligation and the right, respectively, because they are impossible of transmission, are extinguished. Example: to install a motor in a ship that is lost after the perfection of the contract but before such installation. Legal Impossibility • Doctrine of Unforeseen Events • Impossibility of performance – one which supervenes after the constitution of the obligation or during its performance. When the act by reason of a subsequent law is prohibited. Example: when the contract involves child labor and a law is subsequently passed prohibiting the same. The impossibility of performance releases the debtor from his obligation provided that there is not fault on the part of the debtor. When the service has become so difficult as to be manifestly beyond the contemplation of the parties, the oblig9or may also be released therefrom, in whole or in part. Rationale: the intention of the parties should govern and if it appears that the service turns out to be so difficult as to have been beyond their contemplation, it would be doing violence to that intention to hold the obligor still responsible. Basis: Rebus sic stantibus – the parties stipulate in the light of certain prevailing conditions, and once these conditions cease to exist the contract also ceases to exist. Philippine National Construction Corp. vs Court of Appeals and So vs Food Fest Land, Inc. • • The Court explained that Article 1267 is not absolute application of the principle of rebus sic stantibus, which would endanger the security of contractual relations. The parties to the contract must be presumed to have assumed the risks of unfavorable developments. “Service” – should be understood as referring to the “performance” of the obligation. Tagaytay Realty, Inc vs Gacutan In order for Article 1267 to apply, the following conditions should concur: 1. The event or change n circumstances could not have been foreseen at the time of the execution of the contract. 2. It makes the performance of the contract extremely difficult but not impossible. 3. The contract is for a future prestation. Note: The doctrine of unforeseen events should apply only to risks that are manifestly beyond the Page | 92 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 contemplation of the parties, or to those absolutely exceptional changes of circumstances, where equity demands assistance for the debtor. It does not apply to risks that are already known or should have been known, to the parties when they entered into their contractual relations. Article 1269. The obligation having been extinguished by the loss of the thing, the creditor shall have all the rights of action which the debtor may have against third persons by reason of the loss. (1186) Right of Creditor to exercise all rights of debtor. Article 1268. When the debt of a thing certain and determinate proceeds from a criminal offense, the debtor shall not be exempted from the payment of its price, whatever may be the cause for the loss, unless the thing having been offered by him to the person who should receive it, the latter refused without justification to accept it. (1185) • • Obligation to deliver determinate thing arising from crime • • When the obligation to deliver a determinate thing arises from a crime, the loss of the thing due for any cause, does not extinguish the obligation. The obligation of the debtor is converted into payment of the value of the thing lost, even when the loss thereof is caused by a fortuitous event. Exception: if the nature of the determinate thing was unjustly refused by the person who should receive it and the thing is thereafter lost through fortuitous event without the fault of the debtor, and before he has incurred in delay, the obligation is deemed extinguished. Two alternative remedies of the debtor: 1. To consign the thing and thereby relieve himself from any further responsibility for such thing. 2. To just keep the thing in his possession, with the obligation to exercise due diligence, subject to the general rules of obligations, but no longer to the special liability imposed by the above article. • • When the thing is lost by reason of an act of the third person and without the fault of the debtor, and before he has incurred in delay, the obligation is extinguished. However, it is only the creditor who is granted the right of action to claim indemnity from the third person, or otherwise the debtor would unjustly be enriched by such loss of his obligation is extinguished and, at the same time, he can still recover indemnity from another. This includes the indemnity which the debtor might have already received by reason of the loss. It is also applicable to money obtained from the insurance of the thing lost or destroyed. SECTION 3 Condonation or Remission of the Debt Article 1270. Condonation or remission is essentially gratuitous, and requires the acceptance by the obligor. It may be made expressly or impliedly. One and the other kind shall be subject to the rules which govern inofficious donations. Express condonation shall, furthermore, comply with the forms of donation. (1187) Article 1271. The delivery of a private document evidencing a credit, made voluntarily by the creditor to the debtor, implies the renunciation of the action which the former had against the latter. If in order to nullify this waiver it should be claimed to be inofficious, the debtor and his heirs may uphold it by proving that the delivery of the document was made in virtue of payment of the debt. (1188) Page | 93 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1272. Whenever the private document in which the debt appears is found in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the creditor delivered it voluntarily, unless the contrary is proved. (1189) Article 1273. The renunciation of the principal debt shall extinguish the accessory obligations; but the waiver of the latter shall leave the former in force. (1190) 2. 3. Article 1274. It is presumed that the accessory obligation of pledge has been remitted when the thing pledged, after its delivery to the creditor, is found in the possession of the debtor, or of a third person who owns the thing. (1191a) Condonation and Remission of Debt Remission – is an act of liberality by which the creditor, who receives no price or equivalent thereof, releases the debtor from the obligation, either in whole or in part, upon the latter’s consent. • • • If an equivalent is given, it ceases to be a remission and becomes either dation in payment, if the creditor receives a thing different from that stipulated. Novation, if the object or principal condition is changed. Compromised, when there is an exchange of concessions to avoid a litigation or to put an end to one already commenced. Act inter vivos – if the remission is intended to be effective during the creditor’s lifetime. The same is essentially a donation. Mortis causa – if the intention is for the remission to be effective only after the creditor’s death and by reason of his death. The same is essentially a legacy of credit. Reason: one cannot simply impose his own generosity upon another person. Requisites: 1. The parties must have the requisite capacity. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 4. 5. a. Inter vivos – the parties must have the capacity to make and accept the donations. b. Mortis causa – the parties must have the capacity to make a will and to inherit. It must be gratuitous. • Otherwise, it will become either dation in payment, novation, or compromise. It must be accepted by the debtor. • Whether done through and act inter vivos or mortis causa. It must not amount to an inofficious donation or legacy. If it is made expressly, it must comply with the forms of donation, if done through an act inter vivos; or with the formalities of a will, if done through an act mortis causa. Kinds of remission A. As to form: 1. Express – where consent is given explicitly and it is required to be made in a certain form. 2. Implied – where consent can be inferred form the acts of the parties. B. As to effectivity: 1. Inter Vivos – when it takes effect during the lifetime of the creditor. 2. Mortis causa – when it takes effect after the death of the creditor. C. As to extent: 1. Total – if the remission involves the entire obligation. 2. Partial – which may either be a remission of the part of the amount, a part of the obligation (such as the accessory obligation of pledge), or an aspect of the obligation (such as solidarity). Requirement of Acceptance and Formalities A. Debtor’s consent is essential Reason: a person could not be allowed to impose his own generosity upon another. Page | 94 • • If the consent of the debtor is not obtained, or when the express remission does not comply with the required formalities, the creditor may not simply consider the obligation as already extinguished by virtue of his unilateral renunciation of the credit. If the creditor unilaterally renounces his credit and fails to demand the performance of the obligation within the allowable prescriptive period, the obligation is extinguished by reason of extinctive prescription or statute of limitations and not by reason of the creditor’s unilateral action. Note: if the private document evidencing the credit is found in the possession of the debtor, it gives rise to a presumption of remission of the debt. • • Burden of proof: Debtor • Formalities Required • If the remission is intended to be effective during the lifetime of the creditor, or through an act inter vivos, the same is essentially a donation and governed by the law on ordinary donation. Example: 1. If the obligation to be remitted involves a delivery of a personal property, the value of which exceeds 5, 000 pesos, both the remission and its acceptance must be in writing, otherwise the remission is not valid. 2. If the obligation to be remitted involves the delivery of a real property, both the remission and its acceptance must be embodied in a public instrument, otherwise the remission is invalid. Presumption of Remission • • Under Article 1272 – if the private document evidencing the credit is found in the possession of the debtor, it will give a rise to a presumption that the creditor voluntarily delivered such document to the debtor. Under Article 1271 – the voluntary delivery of such document by the creditor to the debtor, in turn, gives rise to a presumption of remission of the debt. Applicable only to a private document evidencing the credit. The creditor’s possession of the evidence of debt is proof that the debt has not been discharged by payment and that promissory note in the hands of the creditor is a proof of indebtedness rather than proof of payment. If the private document evidencing the credit is already in the possession of the debtor, the obligation is presumed extinguished by virtue of remission. Burden of proof: creditor Effect of remission of principal or accessory obligation • The remission of the principal debt also results in the extinguishment of the accessory obligations; but the remission of the latter does not affect the former. Reason: the principal obligation may exist without any accessory obligation; but the latter cannot possibly exist without a principal obligation to which it supports. Example: In a contract of loan, if the loan is secured by a pledge of a thing belonging to the debtor, the remission of the loan (the principal obligation) will result in the extinguishment of the pledge (accessory obligation) but the remission of the latter shall leave the former in force. Accessory Obligation of Pledge Article 1274 provides for a presumption of the remission of the pledge when the thing pledged, after its delivery to the creditor, is found in the possession of the debtor, or of a third person who owns the thing. Page | 95 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Reason: A contract of pledge, the thing pledged is delivered by the pledgor to the creditor or to a third person by common agreement. Effect of Merger Upon Guarantors • Pledge – is classified as a real contract under the Civil Code, which requires the delivery of the thing pledged in order for the contract to be perfected. • The law declares the extinguishment of the pledge “if the thing pledged is returned by the pledgee to the pledgor or owner,” and “any stipulation to the contrary shall be void.” SECTION 4 Confusion or Merger of Rights Article 1275. The obligation is extinguished from the time the characters of creditor and debtor are merged in the same person. (1192a) Article 1276. Merger which takes place in the person of the principal debtor or creditor benefits the guarantors. Confusion which takes place in the person of any of the latter does not extinguish the obligation. (1193) Article 1277. Confusion does not extinguish a joint obligation except as regards the share corresponding to the creditor or debtor in whom the two characters concur. (1194) • The obligation of the guarantor is merely an accessory obligation, the extinguishment of the principal obligation by virtue of the merger involving the principal creditor and the debtor will necessarily result in the extinguishment of the accessory obligation. Any merger involving the persons of the guarantor and the principal creditor will only result in the extinguishment of the accessory obligation but the principal obligation shall remain. Effect of Merger in Joint Obligation • • • • Various credits or debts in a joint obligation are considered distinct from one another. The extinction of the debt of one of the various joint debtors does not necessarily affect the debt of the others. If merger takes place in a joint obligation, the same does not extinguish the obligation “except as regard the share corresponding to the creditor or debtor in whom the two characters concur.” With respect to solidary obligation, Article 1215 of the Civil Code provides that the confusion has the effect of extinguishing the obligation if the confusion affects the entire obligation. Confusion or Merger of Rights Confusion or Merger – is the meeting of one person of the qualities of creditor and debtor with respect to the same obligation. • It takes place when the debtor find himself to be the creditor of the same obligation. Example: “A” executes a promissory note payable to the order of “B.” “B” uses the same promissory note to pay “C” and he endorses and delivers the note to the latter. “C,” in turn, negotiated the instrument back to “A.” “A” will then find himself to be the creditor of his own debt. Hence, the obligation is extinguished by reason of confusion or merger. SECTION 5 Compensation Article 1278. Compensation shall take place when two persons, in their own right, are creditors and debtors of each other. (1195) Compensation – a mode of extinguishing to the concurrent amount the obligations of persons who in their own right and as principals are reciprocally debtors and creditors of each other. • Compensation in effect presupposes a process of balancing simultaneously two obligations in order to extinguish them to the amount in which one is covered by the other. Page | 96 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Compensation is a specie of abbreviated payment, which gives to each of the parties a double advantage: and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated; (3) That the two debts be due; 1. Facility of payment 2. Guaranty for the effectiveness of credit (4) That they demandable; be liquidated and Kinds of Compensation: (5) That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and communicated in due time to the debtor. (1196) As to its effect: 1. Total – the two obligations are of the same amount and compensation operates fully extinguishing both obligations. 2. Partial – two obligations are of different amounts and a balance remains. Article 1280. Notwithstanding the provisions of the preceding article, the guarantor may set up compensation as regards what the creditor may owe the principal debtor. (1197) As to their cause or origin 1. Legal Compensation – takes place by operation of law when all the requisites are present. 2. Voluntary or conventional compensation – takes place when the parties agree to compensate their mutual obligations even in the absence of some requisites. 3. Judicial Compensation – takes place by virtue of an order of the court where the counterclaim of the defendant is allowed to be set-off against the claim of the plaintiff. 4. Facultative – when it can be claimed by the party who can oppose it and who is only party prejudiced by the compensation, as happens when one of the obligations has a period for the benefit of one party alone and the latter renounces the period with the effect of making the obligation due and therefore compensable. Article 1279. In order that compensation may be proper, it is necessary: (1) That each one of the obligors be bound principally, and that he be at the same time a principal creditor of the other; (2) That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind, Requisites: 1. That the parties are mutually creditors and debtors of each other, in their own right and as principals. 2. That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind, and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated; 3. That the two debts be due; 4. That they be liquidated and demandable; 5. That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and communicated in due time to the debtor. Requisite No. 1: As to Parties For compensation to take place the parties must be: 1. Mutual debtors and creditors of each other 2. In their own right 3. As principals Mutual Debtors and Creditors • Requires confluence in the parties of the characters of mutual debtors and creditors, although their right as such debtors need not Page | 97 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 spring from one and the same contract or transactions. As Principals • Tax vs Debt • • Debt are due to the Government in its corporate capacity. Taxes are due to the Government in its sovereign capacity. Example: The lessor was ordered to pay his lessee attorney’s fees in the amount of 500 pesos in a case filed by the former against the latter. After the judgement became final, the lessee obtained a writ of execution of the judgement for attorney’s fees. The lessor interposed the defense of legal compensation because the lessee owed him 4, 320 for unpaid debts. It is also necessary that the parties must be bound principally in order for legal compensation to take place. Hence, there can be no legal compensation if one is a mere guarantor in one of the obligations. Example: A is the guarantor when X borrowed a sum of money from Y. But Y is also indebted to A. Here, there can be no legal compensation between A and Y because the former is not the principal debtor in the first obligation. • The provision simply follows the principle that since the guaranty is merely an accessory obligation, the extinguishment of the principal obligation will also result in the extinction of the former. Requisite No. 2: As to Objects The Court ruled that the attorney’s fees may properly be the subject of legal compensation because the award is made in favor of the litigant, not of his counsel. In other words, it is the litigant, not his counsel, who is the judgement creditor and who may enforce the judgement by execution. In their own right • Legal compensation cannot take place if the parties are not, in their own right, reciprocally creditors and debtors of each other. Hence, if a party has a debt or credit in his personal capacity, it cannot be compensated by a claim or debt in his representative capacity. Example: X is indebted to Y in a promissory note for 100, 000 pesos. Thereafter, X sold the property of A to Y, in his capacity as the guardian of the ward A. Here, there can be no legal compensation because Y is not actually indebted to X. The latter is a creditor of Y in a representative capacity only and not in his own right. In order for the compensation to take place, both debts must consist: 1. In payment of a sum of money. 2. In the delivery of fungibles. Note: If both debts consist of delivery of fungibles, it is necessary that the fungibles be of the same kind, and also the same quality if the latter has been stated. Fungibles vs Consumable Fungibles Is that which can be substituted by another thing of the same kind and quality. Consumable refers to movable property which cannot be used in a manner appropriate to its nature without it being consumed. The classification is The classification is based on the based on the very intention or will of nature of the object the parties. itself. Page | 98 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Requisite No. 3: As to Maturity • Legal compensation cannot take place unless both debts are already due. Requisite No. 5: Absence of Retention or Controversy. • Example: If the obligation is payable on demand, in the absence of a demand, the obligation is not yet due. Therefore, this obligation may not be subject to compensation for lack of a requisite under the law. Requisites No. 4: As to remendability and liquidation • • • • If one of the obligations is a natural obligation, void, or unenforceable, it cannot be compensated because it is not a demandable debt. When one or both debts are rescissible or voidable, they may be compensated against each other before they are judicially rescinded or avoided because prior to the rescission or annulment declared by the court they are considered valid and enforceable obligations. But once these obligations are rescinded or annulled by a final judgement of the court, the compensation is deemed not to have taken place because the rescission or annulment has retroactive effects. A debt is liquidated when its existence and amount are determined, or when the amount is determinable by inspection of the terms and conditions of relevant documents. The controversy must be communicated in due time to prevent compensation from taking place. By “in due time” should mean the period before legal compensation is supposed to take place, considering that legal compensation operates so long as the requisites concur, even without any conscious intent on the part of the parties. Debts payable at a different place • If the foregoing requisites are present, compensation shall take place by operation of law even though the debts may be payable at different places. Basis: an indemnity for expenses of exchange or transportation to the place of payment. Such indemnity is required to be paid by the party claiming the compensation. Example: If one debt is payable in Manila and other debt is payable in Singapore, the fact that the debts are payable in different places is not an obstacle to legal compensation but the indemnity for expenses for exchange or transportation is required to be paid by the party claiming the compensation. Article 1281. Compensation may be total or partial. When the two debts are of the same amount, there is a total compensation. (n) Debt vs Claim Debt An amount actually ascertained. A claim which has been formally passed upon by the courts or quasijudicial bodies to which it can in law be submitted and has been declared to be a debt. Claim Is a debt in embryo. It is mere evidence of a debt and must pass thru the process prescribed by law before it develops into what is properly called a debt. Article 1282. The parties may agree upon the compensation of debts which are not yet due. (n) Article 1283. If one of the parties to a suit over an obligation has a claim for damages against the other, the former may set it off by proving his right to said damages and the amount thereof. (n) Article 1284. When one or both debts are rescissible or voidable, they may be compensated against each other before they are Page | 99 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 judicially rescinded or avoided. (n) Conventional or Voluntary Compensation • • • takes place when the parties agree to compensate their mutual obligations even in the absence of some requisites. The parties may agree upon the compensation of debts which are not yet due. Its minimum requirement is that the parties must be mutually creditors and debtors of each other. Effect of Assignment of Credit Assignment of Credit – an agreement by virtue of which the owner of a credit by a legal cause – such as sale, dation in payment or exchange or donation – and without need of the debtor’s consent, transfers that credit and its accessory rights to another, who acquires the power to enforce it, to the same extent as the assignor could have enforced it against the debtor. Effect of Assignment Upon Compensation Assignment AFTER compensation Requisites: 1. That each of the parties can dispose of the credit he seeks to compensate. 2. That they agree to the mutual extinguishment of the credits. Judicial Compensation • There can be compensation of debts where the amounts are not yet liquidated because the existence of the debt and its amount may be established and determined with certainty in the very case where the set off is pleaded. Article 1285. The debtor who has consented to the assignment of rights made by a creditor in favor of a third person, cannot set up against the assignee the compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor, unless the assignor was notified by the debtor at the time he gave his consent, that he reserved his right to the compensation. If the creditor communicated the cession to him but the debtor did not consent thereto, the latter may set up the compensation of debts previous to the cession, but not of subsequent ones. If the assignment is made without the knowledge of the debtor, he may set up the compensation of all credits prior to the same and also later ones until he had knowledge of the assignment. (1198a) When the assignment of rights is made by the creditor only after legal compensation has already taken place, the same can no longer affect the debtor because the latter’s obligation had already been extinguished. Remedy: the remedy of the assignee is to file an action against the assignor for eviction or damages in view of the fraud committed by the latter. Exception: when the debtor consented to the assignment and failed to reserve his right to the compensation, in which case he is deemed to have waived his right to the compensation. But if he reserved his right to the compensation when he gave his consent, he is not deemed to have abandoned the compensation that had already taken place. Assignment Before Compensation The right of the debtor to set up against the assignee any compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor shall depend of the following: 1. Whether or not the assignment is made with his knowledge. 2. If made with his knowledge, whether or not he consented thereto 3. If he consented, whether or not he reserved his right to the compensation. When debtor consented to assignment Rule: When debtor consented to the assignment made by the creditor, he cannot set up against the Page | 100 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 assignee the compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor. Exception: if the debtor notified the assignor, at the time he gave consent, that he was reserving his right to the compensation, he can still set up against the assignee any compensation that would pertain to him against the assigned credit should all requisites of legal compensation be present. Debts which cannot be compensated 1. 2. 3. 4. Debts arising from contracts of depositum Debts arising from contracts of commodatum Claims for support due by gratuitous title Debts consisting in civil liability arising from a penal offense • The creditor in any of the foregoing obligations can demand for the performance of the obligation even if he is also indebted to the debtor and all requisites of legal compensation are present. However, it is only the debtor in any of the foregoing obligations who is not allowed to set up compensation. The creditor on the other hand, may set up compensation with respect to debts that he owed to the debtor. When debtor did not consent to assignment • If the debtor was notified of the assignment but he did not consent thereto, he may set up the compensation of debts previous to the assignment, but not of subsequent ones. • • Without knowledge of the debtor • • If the assignment is made without the knowledge of the debtor, he may set up the compensation of all credits prior to the same and also later ones until he had knowledge of the assignment. The debtor is allowed to set up against the assignee all credits he have against the assignor, provided that such credits have become due and demandable prior to the notice of the assignment Article 1286. Compensation takes place by operation of law, even though the debts may be payable at different places, but there shall be an indemnity for expenses of exchange or transportation to the place of payment. (1199a) Article 1287. Compensation shall not be proper when one of the debts arises from a depositum or from the obligations of a depositary or of a bailee in commodatum. Neither can compensation be set up against a creditor who has a claim for support due by gratuitous title, without prejudice to the provisions of paragraph 2 of article 301. (1200a) Article 1288. Neither shall there be compensation if one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a penal offense. (n) Example: in obligations arising from a crim, it is only the offender who is prohibited from invoking compensation against any claim that he has with the offended party; but the latter can interpose compensation against any claim which the offender has against him. Article 1289. If a person should have against him several debts which are susceptible of compensation, the rules on the application of payments shall apply to the order of the compensation. (1201) Article 1290. When all the requisites mentioned in article 1279 are present, compensation takes effect by operation of law, and extinguishes both debts to the concurrent amount, even though the creditors and debtors are not aware of the compensation. (1202a) Effects of Legal Compensation • When all the requisites mentioned in Article 1279 are present, compensation takes effect by operation of law, and extinguishing both debts to the concurrent amount, even though the creditors and debtors are not aware of the compensation. Page | 101 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • SECTION 6 Novation Article 1291. Obligations may be modified by: (1) Changing their object or principal conditions; (2) Substituting the person of the debtor; (3) Subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. (1203) Novation • • • • The extinguishment of an obligation by the substitution or change of the obligation by a subsequent one which extinguishes or modifies the first, either by changing the object or principal conditions, or by substituting the person of the debtor, or by subrogating a third person to the rights of the creditor. A juridical act with a dual function – it extinguishes an obligation and creates a new one in lieu of the old. It is not a complete obliteration of the obligorobligee relationship, but operates as a relative extinction of the original obligation in the sense that by novation, obligations are not extinguished but rather substituted with another. The effect of novation is either to modify or extinguish the original contract. Kinds of Novation As to extent 1. Extinctive (total novation) – when an old obligation is terminated by the creation of a new one that takes the place of the former. • The obligation is completely extinguished. 2. Modificatory (partial novation) – the old obligation subsists to the extent that it remains compatible with the amendatory agreement. There is only a modification or change in some principal conditions of the obligation. As to its essence 1. Objective novation (real novation) – occurs when there is a change of the object, cause, or principal conditions of an existing obligation. 2. Subjective novation (personal novation) – occurs when there is a change of either the person of the debtor, or of the creditor in an existing obligation. 3. Mixed novation – when the change of the object, cause or principal conditions of an obligation occurs at the same time with the change of either in the person of the debtor or creditor. As to its form or constitution 1. Express – when the new obligation declares in unequivocal terms that the old obligation is extinguished. 2. Implied – when the new obligation is incompatible with the old ne on every point. Requisites of Novation 1. There must be a previous valid obligation 2. There must be an agreement of the parties concerned to a new contract. 3. There must be the extinguishment of the old contract 4. There must be the validity of the new contract. Previous Valid Obligation • • It is necessary that the original obligation exists and that the same is valid. Article 1292 – it is only when the original obligation is void that the novation also becomes void. There will be a valid novation even if the original obligation is voidable in two instances: Page | 102 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. When there has been a ratification of the obligation prior to the novation inasmuch as ratification cleanses the obligation of its defects from the very beginning. 2. If the defect can be claimed only by the debtor because he consents to the novation, he renounces his right to annul the old obligation. Extinguishment of Obligation • • Note: • • The latter exception is always true in delegacion, where the initiative for the substitution emanates from the original debtor; hence, he necessarily consents to the same. Expromision, the same may be made without the knowledge of even against the will of the original debtor, in which case there would be no implied ratification of the old obligation and, hence, should the new debtor demand reimbursement from the original debtor, the latter can still interpose the nullity of the original obligation. New Valid Obligation • • Villaroel vs Estrada • • The first requisite does not require that the obligation be a civil one because even a natural obligation can be novated. It can also be said that the novation of a prescribed debt is valid because prescription, being a defense available only to the debtor, can be waived by him and he does so by voluntarily promising to pay the prescribed debt in case of a novation. New Contract • • There is neither a valid new contract nor a clear agreement between the parties to a new contract, there is no novation. Since novation is effected only when a new contract has extinguished an earlier contract between the same parties, it necessarily follows that there could be no novation if the parties in the new contract are not the same parties in the old contract. In order that an obligation may be extinguished by another which substitute the same, it is imperative that it be so declared in unequivocal terms, or that the old and the new obligations be on every point incompatible with each other. The four essential elements of novation and the requirement that there be total incompatibility between the old and the new obligation, are applicable only to an extinctive novation, because in modificatory novation the obligation is simply modified not extinguished. • • If the new obligation is void, the extinguishment of the original obligation is not realized, because that which is null and void cannot produce effect. Hence, there is no novation. However, even when there is no novation because of the nullity of the new obligation, Article 1297 provides that the original obligation is deemed extinguished if “the parties intended that the former relation should be extinguished in any event.” The rule applies only if the new obligation is void ab initio. If the obligation is merely voidable, novation can still take place because voidable obligation is considered valid until annulled by a final judgement of a competent court. Article 1292. In order that an obligation may be extinguished by another which substitute the same, it is imperative that it be so declared in unequivocal terms, or that the old and the new obligations be on every point incompatible with each other. (1204) Novation is never presumed • • Novatio non praesumitur – novation is never presumed. For novation to be a jural reality, its animus must be ever present, debitum pro debito – Page | 103 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • • • basically extinguishing the old obligation for the new one. Novation is never presumed, and the animus novandi, whether totally or partially, must appear by express agreement of the parties, or by their acts that are too clear and unmistakable. To effect an objective novation, it is imperative that the new obligation expressly declare that the old obligation is thereby extinguished, or that the new obligation be on every point incompatible with the new one. The term “expressly” means that the contracting parties incontrovertibly disclose that their object in executing the new contract is to extinguish the old one. Upon the other hand, no specific form is required for an incompatibility between the two contracts. Implied novation necessitates that the incompatibility between the old and new obligation be total on every point such that the old obligation is completely superseded by the new one. The test of incompatibility is whether the two obligations can stand together, each one having an independent existence; if they cannot and are irreconcilable, the subsequent obligation would also extinguish the first. When not expressed, incompatibility is required so as to ensure that the parties have indeed intended such novation despite their failure to express it in categorical terms. The incompatibility must take place in any of the essential elements of the obligation in order for extinctive novation to occur: 1. The juridical relation or tie, such as from a mere commodatum to lease of things, or from negotorium gestio to agency, or from a mortgage to antichresis; or from sale to one of loan. 2. The cause, object or principal conditions, such as a change of the nature of the prestation. 3. The subjects, such as the substitution of a debtor or the subrogation of the creditor. • agreement is merely incidental to the main obligation, such as a change in the interest rate, an extension of the time to pay or a change in the period to comply with the obligation. Article 1293. Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor in the place of the original one, may be made even without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, but not without the consent of the creditor. Payment by the new debtor gives him the rights mentioned in articles 1236 and 1237. (1205a) Article 1294. If the substitution is without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, the new debtor's insolvency or non-fulfillment of the obligations shall not give rise to any liability on the part of the original debtor. (n) Article 1295. The insolvency of the new debtor, who has been proposed by the original debtor and accepted by the creditor, shall not revive the action of the latter against the original obligor, except when said insolvency was already existing and of public knowledge, or known to the debtor, when the delegated his debt. (1206a) Expromision vs Delegacion Expromision Delegacion The initiative for the The debtor offers, change does not and the creditor come from – and accepts, a third may even be made person who without the consents to the knowledge of – the substitution and debtor, since it assumes the consists of third obligation. person’s assumption of the obligation. It logically requires The consent of the consent of the these three persons third person and the are necessary. creditor. The original debtor must be released from the obligation; otherwise, there can be no valid novation. The novation is merely modificatory where the change brought about by any subsequent Page | 104 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Release of Original Debtor • • In order to change the person of the debtor, the old one must be expressly released from the obligation, and the third person or new debtor must assume the former’s place in the relation. Without the express release of the debtor from the obligation, any third party who may thereafter assume the obligation shall be considered merely as co-debtor or surety. • Effect of Non-fulfillment of insolvency of new debtor • Magdalena Estates Inc. vs Rodriguez • • If it is not clearly shown that the original debtor has been released from the obligation, the fact that the creditor accepts payment from a third person who has assumed the obligation will result merely to the addition of debtors and not novation. Hence, the creditor may therefore enforce the obligation against both debtors. The existence of the creditor’s consent may also be inferred from the creditor’s act, but such acts still need to be clear and unmistakable expression of the creditor’s consent. • Whether the substitution of the debtor is expromision or delegacion, the effect is the same, that is the release of the original debtor from the obligation. If the new debtor fails to fulfill his obligation to the creditor for whatever reason, even by reason of his insolvency, the same shall not ordinarily give rise to any liability on the part of the original debtor. In delegacion, the rule admits of exceptions. If the new debtor fails to perform the obligation by reason of his insolvency, the action can be revived against the original debtor in two instances: Consent of Creditor De Cortes vs Venturanza Reason: substitution of one debtor for another may delay or prevent the fulfillment of obligation by reason of the financial inability or insolvency of the new debtor; hence, the creditor should agree to accept the substitution in order that it may be binding on him. Testate Estate of Lazaro Mota vs Serra General Rule: since novation implies a waiver of the right the creditor had before the novation such waiver must be EXPRESS. 1. When the insolvency of the new debtor was already existing and of public knowledge at the time the old debtor delegated his debt. 2. When such insolvency was already existing and known to the old debtor at the time, he delegated his debt. Article 1296. When the principal obligation is extinguished in consequence of a novation, accessory obligations may subsist only insofar as they may benefit third persons who did not give their consent. (1207) Affect of Novation on Accessory Obligations Accessory vs Principal Reason: since novation extinguishes the personality of the first debtor who is to be substituted by a new one, it implies on the part of the creditor a waiver of the right that he had before the novation, which waiver must be express under the principle that renuntiatio non praesumitor, be perform unless the will to waive is indisputably shown by him who holds the right. Asia Banking Corporation vs Elser Accessory Principal Dependent for its May exist without existence on a an accessory principal obligation. obligation. Example: The contract of mortgage is an accessory obligation to guarantee the performance of the main obligation Page | 105 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 of indebtedness in a contract of loan. The loan can exist without the mortgage but the mortgage cannot exist without the loan, which is the principal obligation. • When principal obligation is extinguished in consequence of novation, accessory obligations are also extinguished. Exception: 1. When the accessory obligation is for the benefit of a third person and the latter did not give his consent to the novation, because in reality it is distinct obligation. 2. When the guarantors and sureties agree to be bound in the new obligation. The effects of novation referred to in Article 1296 are applicable only to the following forms: 1. By changing the cause, object or principal conditions. 2. By substituting the person of the debtor. Article 1297. If the new obligation is void, the original one shall subsist, unless the parties intended that the former relation should be extinguished in any event. (n) Article 1298. The novation is void if the original obligation was void, except when annulment may be claimed only by the debtor or when ratification validates acts which are voidable. (1208a) (See Requisites of Novation) Article 1299. If the original obligation was subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the new obligation shall be under the same condition, unless it is otherwise stipulated. (n) Example: 1. If the condition to which the old obligation is subjected to is a suspensive one, the obligation does not arise except from the fulfillment of the condition. Hence, one of the requisites extinctive novation is lacking, that is, the existence of a previous valid obligation. 2. If the condition is resolutory, the happening of the condition would result in the extinguishment of the old obligation. Hence, there would also be no novation because of the absence of a previous valid obligation. In both instances, the novation must be held conditional also, and its efficacy depends upon whether condition which affects the original obligation is complied with or not. Exception: when there is a stipulation to the contrary, that is, when the intention of the parties is to do away with the condition and substitute the conditional obligation with a pure one. In such case, the old obligation disappears and the new one is substituted in its place. When both Obligations are conditional • • • • When Original Obligation is Conditional • If the original obligation is subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the new obligation must necessarily be subject to the same condition. • If both the old and new obligations are subject to different conditions, the effect is determined by the compatibility or incompatibility of the condition. If the conditions in both obligations can stand together, all conditions in both obligations must be fulfilled in order for the novation to be effective. If only the conditions in the old obligation are complied with while those in the new obligation are not, there would be no novation because of the absence of a new valid obligation. If only the conditions in the new obligation are complied with while those in the old obligation are not, there would also be no novation because of the absence of a previous valid obligation. If the conditions in both obligations are incompatible with each other, there will exist a case of an implied novation resulting in the Page | 106 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 extinguishment of the old obligation and its substitution by the new one, subject to its conditions. Article 1300. Subrogation of a third person in the rights of the creditor is either legal or conventional. The former is not presumed, except in cases expressly mentioned in this Code; the latter must be clearly established in order that it may take effect. (1209a) Article 1301. Conventional subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the third person. (n) Article 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation: (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor's knowledge; (2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor; (3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter's share. (1210a) Subrogation • • Takes place when there is a change in the person of the creditor. The transfer of all the rights of the creditor to a third person, who substitute him in all his rights. Legal Subrogation – takes place without agreement but by operation of law because of certain acts. Conventional Subrogation – takes place by agreement of parties. CONVENTIONAL SUBROGATION • • Art. 1300 – conventional subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the third person. It must be clearly established in order that it may take effect and the burden of proof rests upon him who claim its existence. Conventional Subrogation vs Assignment of Credit Assignment of Credit – an agreement by virtue of which the owner of the credit, by legal cause – such as sale, dation in payment, or exchange or donation – and without need of debtor’s consent, transfers that credit and its accessory rights to another, who acquires the power to enforce it, to the same extent as the assignor could have enforced it against the debtor. Conventional Subrogation Debtor’s consent is necessary Extinguishes the obligation and gives rise to a new one. Nullity of an old obligation may be cured such that a new obligation will be perfectly valid. • Assignment of Credit Debtor’s consent is not necessary Refers to the same right which passes from one person to another. Nullity of an obligation is not remedied by the assignment of the creditors to another. What the law requires in an assignment of credit is not the consent of the debtor, but merely notice to him as the assignment takes effect only from the time, he has knowledge thereof. In ascertaining the character of the transaction as to whether it is an assignment of credit or conventional subrogation, the determinative factor is the intention of the parties. Example: If the intention of the parties is that the agreement would not become valid and effective in the absence Page | 107 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 of the debtor’s consent, the transaction is one of conventional subrogation and of an assignment of credit. • If the parties intended their transaction to be that of conventional subrogation but the debtor’s consent was not obtained, the conventional subrogation was never perfected, the transaction may not be treated as a case of an assignment of credit. remainder, and he shall be preferred to the person who has been subrogated in his place in virtue of the partial payment of the same credit. (1213) Effects of Subrogation 1. In case of Total Subrogation • LEGAL SUBROGATION • Legal subrogation is not presumed except ONLY in the following cases: 1. When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor’s knowledge. Example: A is indebted to B for 1, 000, 000 pesos secured by a mortgage. A is also indebted to C for 500, 000 pesos, without any collateral. B is preferred creditor compared to C. If C will pay B the amount of 1, 000, 000 pesos, he will be subrogated to all the rights of B even if he made the payment without the knowledge of A. In this situation, A can still set up against C the defenses which he could have used against B, such as compensation, payments already made, or even any vice or defect of the former obligation. 2. When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor. 3. When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter’s share. It does not obliterate the obligation of the debtor, but merely puts the assignee in the place of his assignor. The rule stated in Article 1303 absolutely applies to legal subrogation but not so in conventional subrogation. Reason: Since conventional subrogation is a new contractual relation based on the mutual agreement among all the necessary parties, the parties are free to stipulate as to the effect of their agreement on the accessory obligations accompanying the original obligation. 2. In Case of Partial Subrogation • • The creditor may still exercise his right with respect to the remainder of the with respect to the remainder of the debt while the third person may exercise his right up to the extent of what he had paid to the creditor. In the event, however that the assets of the debtor will no longer be sufficient to pay both creditors, Article 1304 provides that the original creditor shall be preferred to the person who has subrogated in his place in virtue of the partial payment of the same credit. Article 1303. Subrogation transfers to the persons subrogated the credit with all the rights thereto appertaining, either against the debtor or against third person, be they guarantors or possessors of mortgages, subject to stipulation in a conventional subrogation. (1212a) Article 1304. A creditor, to whom partial payment has been made, may exercise his right for the Page | 108 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 TITLE II CONTRACTS • CHAPTER 1 General Provisions A contract may be entered into involving a single person so long as he is representing two different parties, for he may act in his own right and as representative of another. Example: Article 1305. A contract is a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. (1254a) Contract • • a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. A juridical convention manifested in legal form, by virtue of which one or more persons bind themselves in favor of another, or others, or reciprocally, to the fulfillment of a prestation to give, to do, or not to do. “Meeting of minds” • • This meeting of the minds speaks of the intent of the parties in entering into the contract respecting the subject matter and the consideration thereof. There can be no contract in the true sense in the absence of the element of agreement, or of mutual assent of the parties, for consent is the essence of a contract. Note: • • There can be no quasi-contract of negotiorum gestio if in the fact the manager has been tacitly authorized by the owner. What will exist between the parties is an implied contract of agency and not the quasicontract of negotiorum gestio. Auto-Contract • While the definition of Article 1305 mentions of the meeting of minds between two persons, what is actually meant by the provision is two parties and not two persons. Article 1890 of the Civil Code allows the agent himself to be the lender if he has been empowered by his principal to borrow money, provided that he lends at the current rate interest. • • • In such a case, the law authorizes the agent to contract with himself because he is representing two parties: (1) as the lender in his personal capacity; and (2) as the agent of the barrower. Here, a possible conflict of interest is avoided because he is allowed to lend only at the current rate of interest. On the other hand, if the agent has been authorized to lend money at interest, the same article prohibits him from borrowing the money without the consent of the principal, for the purpose of avoiding any conflict of interest. Characteristics of Contracts 1. Obligatory force of contracts – obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the parties and should be complied with in good faith. 2. Autonomy of contracts – the contracting parties may establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. 3. Mutuality of Contracts – the contract must bind both contracting parties and the validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them. 4. Relativity of Contracts – contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs, except in case where the rights and obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. Page | 109 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Classification of Contracts b. Real • According to the degree of dependence a. Preparatory • That which is not an end by itself but only a means for the execution of another contract. Example: 1. Agency is a preparatory contract, as agency does not stop with the agency because the purpose is to enter into other contracts. 2. An option is another preparatory contract in which one party grants to the other, for a fixed period and under specified conditions, the power to decide, whether or not to enter into a principal contract. b. Principal • That which can exist independently of other contracts because it has its own purpose which does not depend upon any other contract. Example: loans, sales, or leases c. Accessory • That which cannot exist as an independent contract since it consideration is the same as that of the principal. Example: pledges, mortgages, and suretyship. According to perfection That which is perfected only upon the delivery of the object of the contract. Example: deposit, pledge, commodatum, contract of simple loan, or mutuum. According to nature of obligation produced a. Unilateral • That which creates obligations only on one side or on the part of only one of the contracting parties. Example: Commodatum which is essentially gratuitous and creates obligations only on the side of the bailee. b. Bilateral • That which creates obligations on both sides or on both parties. • The contracting parties are mutually creditors and debtors. Example: contract of sale • • it creates obligations on both parties. The seller obligates himself to transfer the ownership of and to deliver the thing sold while the buyer obligates himself to pay the purchase price. According to name Example: a. Nominate (contrato nominado) • That which has an individuality of its own and is distinguished by a particular or special name in the Civil Code, such as sale, lease, deposit, barter, pledge, etc. • It is governed by the special rules of law applicable to it. Sale is a consensual contract and is perfected by mere consent, which is manifested by a meeting of the minds as to the offer and acceptance thereof on the subject matter, price and terms of payments of the price. b. Innominate (contrato innominado) • That which is without any individuality of its own and not specifically named or classified in the Civil Code although recognized by it. a. Consensual • Perfected by mere consent or upon mere meeting of the minds. Page | 110 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 According to Cause a. Onerous • That where the cause is understood to be, for each contracting party, the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other. Example: the contract of sale, option contract. b. Remuneratory • That where the cause is the service or benefit for which the remuneration is given. Example: a donation given in consideration of a past service which does not amount to a demandable debt. c. Gratuitous • That where the cause is the mere liberality of the benefactor. Example: the contract of commodatum is essentially gratuitous. According to risk involved a. Commutative • That in which each of the contracting parties gives and receives an equivalent or there is a mutual exchange of relative values. Example: the contract of sale where the seller deli9vers the thing sold in exchange for the purchase price and the buyer pays the price in exchange for the thing sold. Example: the contract of insurance According to requirement of form or solemnity a. Common • That which does not require any form. • As a rule, contracts are obligatory in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the essential elements of a contract are present. b. Special or solemn • That which requires certain formalities either for its validity or enforceability. Example: The donation of real property and its acceptance are required to be embodied in a public instrument; otherwise, the donation is void. The sale over a real property or any interest therein, if still purely executory, is required to be in writing; otherwise it is unenforceable. According to purpose a. b. c. d. To transfer ownership (sale or barter) To convey the use (commodatum or lease) To give security (pledge or mortgage) To render some service (agency) According to their subject matter a. Things (sale, pledge, mortgage) b. Services (lease of service, or agency) c. Rights (provided that the same are not personal or intransmissible) According to their defects b. Aleatory • That in which each of the parties or both reciprocally bind themselves to give or to do something in consideration of what the other shall give or do upon the happening of an event which is uncertain, or which is to occur at an intermediate time. • The element of risk dependent on chance is predominant. a. b. c. d. e. Perfectly valid (not suffering from defect) Rescissible Voidable Unenforceable Void or Inexistent Article 1306. The contracting parties may establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, Page | 111 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 good customs, public order, or public policy. (1255a) • Autonomy of Contract Autonomy of Contracts/Principle of Party Autonomy in Contracts/Freedom of Contract • The contracting parties are accorded the liberty and freedom to establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided the same are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. Constitutionally Protected Right • • • The right to enter into lawful contracts is not based on Article 1306 of the Civil Code. The function of the said article, aside from recognizing the existence of such right, is simply to provide for limitations in the exercise of the freedom of contract. Neither did such right derive its origin from the Constitution. The function of the Constitution, apart from recognizing the existence of such right, is to guarantee and protect the freedom of contract against unwarranted and arbitrary interference by the State. • Non-impairment Clause Purpose: to safeguard the integrity of contracts against unwarranted interference by the State. • • • A law which changes the terms of a legal contract between parties, either in the time or mode of performance, or imposes new conditions, or dispenses with the expressed, or authorizes for its satisfaction something different from that provided in its terms, is law which impairs the obligation of a contract and is therefore null and void. • The prohibition against impairment of the obligation of contracts is aligned with the general principle that laws newly enacted have only prospective operation, and cannot affect acts or contracts already perfected; however, as to laws already in existence, their provisions are read into contracts and deemed a part thereof. • While non-impairment of contracts is constitutionally guaranteed, the rule is not Basis: Due Process Clause • The Constitution guarantees the free exercise of the right of property, and the freedom to contract is such right, of which the Contracts should not be tampered with by subsequent laws that would change or modify the rights and obligations of the parties. However, the constitutional prohibition on the impairment of the obligation of contract does not prohibit every change in existing laws, and to fall within the prohibition, the change must not only impair the obligation of the existing contract, but the impairment must be substantial. Clemons vs Nolting To enter into a contract freely and without restraint is one of the liberties guaranteed to the citizens of the country and should not be lightly interfered with. 1. Article III, Section 1. No law shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law. 2. Article III, Section 10. No law shall be passed impairing obligation of contracts. possessor cannot be deprived without due process of law. The Constitution allows deprivation of liberty, including liberty of contract, as long as due process is observed. The liberty to contract maybe subjected, in the interest of the general welfare under the police power, to restrictions varied in the character and wide ranging in scope as long as due process is observed. Page | 112 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • absolute, since it has to be reconciled with the legitimate exercise of police power. As long as the contract affects the public welfare one way or another so as to require the interference of the State, then must be the police power be asserted, and prevail, over the impairment clause. Ortigas & Co., Limited Partnership vs Feati Bank and Trust Co. • Contractual restrictions on the use of property could not prevail over the reasonable exercise of police power through zoning regulations • Freedom of contract is also subject to the limitation that the agreement must not be against public policy and any agreement or contracts made in violation of this rule is not binding and will not be enforced. Public Policy • • Principle under which freedom of contract or private dealing is restricted for the good of the community. Courts of justice will not recognize or uphold a transaction when its object, operation, or tendency is calculated to be prejudicial to the public welfare, to sound morality or to civic honesty. Sangalang vs Intermediate Appellate Court Ongsiako vs Gamboa • The power of the Metro Manila Commission and the Makati Municipal Council to enact zoning ordinances for the general welfare prevails over the deed restrictions on the lot owners in Bel-Air Village which restricted the use of the lots for residential purposes only. • Limitations on Freedom of Contract • • Although a contract is the law between the parties, the provisions of positive law which regulate contracts are deemed written therein shall limit and govern the relations between the parties. A contract that violates the Constitution and the law is null and void and vests no rights and creates no obligations. It introduces no legal effect at all. Laws, which by terms of a contract must not contravene are those: 1. Which expressly declare their obligatory character; 2. Which are prohibitive; 3. Which express fundamental principles of justice which cannot be overlooked by the contracting parties; 4. Which impose essential requisites without An agreement is against public policy if it is injurious to the interest of the public, contravenes some established interest of society, violates some public statute, is against good morals, tends to interfere with the public welfare or safety, or, as it is sometimes put, if it is at war with the interests of society and is in conflict with the morals of the time. Ollendorff vs Abrahamson • The term “public order” does not mean the actual keeping of the public peace, but signifies the public weal – that which is permanent, and essential in institutions. It is the equivalent of the term “public policy.” Article 1307. Innominate contracts shall be regulated by the stipulations of the parties, by the provisions of Titles I and II of this Book, by the rules governing the most analogous nominate contracts, and by the customs of the place. (n) Innominate Contracts Purpose: no one should permit to enrich himself to the damage of another. Page | 113 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Pacific Merchandising Corp. vs Consolacion Insurance & Surety Co., Inc. • Where one has rendered services to another, and these services are accepted by the latter, in the absence of proof that the service was rendered gratuitously, it is but just that he should pay a reasonable remuneration therefor. Four kinds of innominate contracts: 1. 2. 3. 4. Do ut des (I give that you give) Do ut facias (I give that you do) Facio ut des (I do that you give) Facio ut facias (I do that you do) Article 1308. The contract must bind both contracting parties; its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them. (1256a) Article 1309. The determination of the performance may be left to a third person, whose decision shall not be binding until it has been made known to both contracting parties. (n) Article 1310. The determination shall not be obligatory if it is evidently inequitable. In such case, the courts shall decide what is equitable under the circumstances. (n) An escalation clause which grants the creditor an unbridled right to adjust the interest independently and upwardly, completely depriving the debtor of the right to assent to an important modification in the agreement is void. Philippine National Bank vs Court of Appeals • • • Contract changes must be made with the consent of the contracting parties. The minds of all parties must meet as to the proposed modification, especially when it affects an important aspect of the agreement, like the rate of interest in loan contracts, for it can make or break a capital venture. Any change must be mutually agreed upon, otherwise, it is bereft of any binding effect. Philippine Savings Bank vs Castillo • • Respondents’ assent to the modifications on the interest rates cannot be implied from their lack of response to the memos sent by petitioner, informing them of the amendments, nor from the letters requesting for reduction of the rates. An escalation clause is void where the creditor unilaterally determines and imposes an increase in the stipulation rate of interest without the express conformity of the debtor. Mutuality of Contracts GF Equity, Inc. vs Valenzona Principle of Mutuality of Contracts • • Based on the principle that the obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the contracting parties, and there must be mutuality between them based essentially on their equality under which it is repugnant to have one party bound by the contract while leaving the other free therefrom. Purpose: to render void a contract containing a condition which makes its fulfillment dependent solely upon the uncontrolled will of one of the contracting parties. Example: It leaves the determination of whether Valenzona failed to exhibit sufficient skill or competitive ability to coach Alaska team solely to the opinion of GF Equity. Whether Valenzona indeed failed to exhibit the required skill or competitive ability depended exclusively on the judgement of GF Equity. In other words, GF Equity was given an unbridled prerogative to pre-terminate the contract irrespective of the soundness, fairness or reasonableness, or even lack of basis of its opinion. Instant cases where the Court upheld the legality of contracts which left their fulfillment or implementation to the will of either of the parties: Page | 114 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Jespajo Realty vs Court of Appeals • The express provision in the lease agreement of the parties that violation of any of the terms and conditions of the contract shall be sufficient ground for termination thereof “by the lessor,” removes the contract from the application of Article 1308. Taylor vs Uy Tieng Piao • • Art. 1308 creates no impediment to the insertion in a contract of personal service of a resolutory condition permitting the cancellation of the contract “by one of the parties”. For where the contracting parties have agreed that such option shall exist, the exercise of the option is as much in the fulfillment of the contract as any other act which may have been the subject of agreement. Allied Banking Corporation vs Court of Appeals • • The fact that such option is binding only on the lessor and can be exercised only by the lessee does not render it void for lack of mutuality. After all, the lessor is free to give or not to give the option to the lessee. And while the lessee has a right to elect whether to continue with the lease or not, once he exercises his option to continue and the lessor accepts, both parties are thereafter bound by the new lease agreement. Contract of Adhesion • • One of the parties imposes a ready-made form of contract, which the other party may accept or reject, but which the latter cannot modify. One party prepares the stipulation in the contract, while the other party merely affixes his signature or his adhesion thereto, giving no room for negotiation and depriving the latter of the opportunity to bargain, because the only participation of the party is the • • • affixing of his signature or his adhesion thereto. These contracts have been declared as binding as ordinary contracts, the reason being that the party who adheres to the contract is free to reject it entirely. If the terms are accepted without objection, then the contract serves as the law between them. The validity must be determined in light of the circumstances under which the stipulation is intended to apply. Determination of Performance by Third Person • • Such determination of the performance by a third person shall be binding upon the contracting parties from the moment it is made known to them, provided that the same is not evidently inequitable. The court shall decide what is equitable under the circumstances. Article 1311. Contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs, except in case where the rights and obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. The heir is not liable beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent. If a contract should contain some stipulation in favor of a third person, he may demand its fulfillment provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. A mere incidental benefit or interest of a person is not sufficient. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person. (1257a) Article 1312. In contracts creating real rights, third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby, subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. (n) Article 1313. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them. (n) Page | 115 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1314. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. (n) Note: The same principle applies to the option to renew the lease. As a general rule, covenants to renew a lease are not personal but will run with the land. Relativity of Contracts DKC Holdings Corporation vs Court of Appeals • The basic principle or relativity of contracts is that contracts can only bind the parties who entered into it, and cannot favor or prejudice a third person, even if he is aware of such contract and has acted with knowledge thereof. Axiom res inter alios acta aliis neque nocet predest • A contract can only obligate the parties who had entered into it, or their successors who assumed their personalities or juridical positions, and that, concomitantly, a contract can neither favor nor prejudice third person. Basis: Article 1311 of the Civil Code • Only the contracting parties are bound by the stipulations in the contract; they are those ones who would benefit from and could violate it. Thus, one who is not a party to a contract, and for whose benefit it was not expressly made, cannot maintain an action on it. Heirs Are Also Bound by Contracts • • A person who enters into a contract is deemed to have contract6ed for himself and his heirs and assigns. The heirs of the contracting parties are precluded from denying the binding effect of the valid agreement entered into by their predecessors-in-interest Example: A contract of lease is generally transmissible to the heirs of the lessor or lessee because a lease contract is not essentially personal in character. It involves a property right and, as such, the death of a party does not excuse non-performance of the contract. • The Contract of Lease with Option to Buy entered into by the predecessor-in-interest is binding upon the heir. Tanay Recreation Center and Development Corp. vs Fausto • The lease contract which contains a right of first refusal into by the predecessor-ininterest is also binding upon the heir. Naranja vs Court of Appeals • When the predecessor-in-interest had already sold the parcels of land prior to his death, the Court held that the heirs are bound by the contract of sale executed by the deceased and, therefore, said parcels of land no longer formed part of the estate which the heirs could have inherited. Exceptions 1. Transmissibility by nature of the right and obligation, refers to a situation where the peculiar individual qualities are contemplated as a principal inducement of the contract. Example: contract intuit personae, or in consideration of the performance by a specific person and by no other. 2. Intransmissibility by stipulation of the parties, being exceptional and contrary to the general rule, should not be easily implied, but must be expressly established, or at the very least, clearly inferable from the provisions of the contract itself. 3. Not transmissible by operation of law. The provision makes reference to those cases where the law expresses that the rights or obligations are extinguished by death, as is the case in legal support, parental authority, Page | 116 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 usufruct, contracts for a piece of work, partnership, and agency. Note: the articles of the Civil Code regulate guaranty or suretyship contain no provision that the guaranty is extinguished upon the death of the guarantor or the surety. 5. Accion directa is allowed by law in certain cases. Stipulation Pour Autrui • Rule on Monetary Debts • • The heir is not liable beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent. When the deceased had left debts, the heirs are not personally liable for such debts of the deceased; such debts must be collected only from the property left upon his death, and if it should not be sufficient to cover all of them, the heirs cannot be made to pay the uncollectible balance. Note: the binding effect of contracts upon the heirs of the deceased party is not altered by the provision in our Rules of Court that money debts of a deceased must be liquidated and paid from his estate before the residue is distributed among said heirs. Reason: whatever payment is made from the estate is ultimately a payment by the heirs and distributes, since the amount of the paid claim in fact diminishes or reduces the share that the heirs would have been entitled to receive. Exceptions to Relativity of Contracts 1. Contracts may confer benefits to a third person or what are otherwise also known as stipulation pour autrui. 2. In Contracts creating real right, third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract may be bound thereby under the provisions of mortgage laws and land registration laws. 3. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them, such that they can ask for their rescission. 4. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract can be made liable for damages of the other contracting party. • It is fundamental that contracts take effect only between the parties thereto, except in some specific instances provided by law where the contract contains some stipulation in favor of a third person. A third person is allowed to avail himself of a benefit granted to him by the terms of the contract, provided that the contracting parties have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon such person. Florentino vs Encarnacion • A stipulation in favor of a third person conferring a clear and deliberate favor upon him, and which stipulation is merely a part of a contract entered into by the parties, neither of whom acted as agent of the third person, and such third person may demand its fulfillment provided that he communicates his acceptance to the obligor before it is revoked. Parties 3 parties to a stipulation pour autrui: 1. The promisor – the party obliged to perform the prestation in favor of the third person. 2. The promise – the party who obtains and accepts the promise. 3. The third person or beneficiary – the party who acquires the right to demand the prestation from the promisor who may be a determinate (particular person) or indeterminate (the prospective beneficiary in life insurance. Limitless Potentials, Inc. vs Quilala The third person may either be: 1. A done beneficiary • If the stipulation is in the nature of gift and for the sole benefit of the third person. Page | 117 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • 2. A creditor beneficiary • Where an obligation is due from the promise to the third person which the former seeks to discharge by means of stipulation, such as when a transfer if property is coupled with the purchaser’s promise to pay a debt owing from the seller to a third person. 3. An incidental beneficiary • Absent the intent to benefit a third person • One who benefits from the contract of anther but whose benefit was not the intent of the contracting parties. • Should the benefit received by the third person be merely incidental, then it is not considered a stipulation pour autrui. A stipulation pour autrui may be divided into two classes: 1. Those where the stipulation is intended for the sole benefit of such person. (The third party is a done) 2. Those where an obligation is due from the promise to the third person which the former seeks to discharge by means of such stipulation (he is a creditor beneficiary) • • Example: the conferment of a favor upon the credit holder in the contract between the credit card company and the merchant (store). Requirement of Acceptance • • In order to constitute a valid stipulation pour autrui it must be the purpose and intent of the stipulating parties to benefit the third person, and it is not sufficient that the third person may be incidentally benefited by the stipulation. There is no time limit; such third person has all the time until the stipulation is revoked. Florentino vs Encarnacion • Requisites of Stipulation Pour Autrui 1. There is a stipulation in favor of a third person. 2. The stipulation is a part, not the whole, of the contract. 3. The contracting parties clearly and deliberately conferred a favor to the third person – the favor is not an incidental benefit. 4. The favor is unconditional and uncompensated. 5. The third person communicated his or her acceptance of the favor before its revocation. 6. The contracting parties do not represent, or are not authorized by, the third party. A third person is allowed to avail himself of a benefit granted to him by the terms of the contract, provided that the contracting parties have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon such person. A third person not a party to the contract has no action against the parties thereto, and cannot generally demand the enforcement of the same. To determine the interest of a third person in a contract is a stipulation pour autrui or merely an incidental interest, is to rely upon the intention of the parties as disclosed by their contract. The acceptance does not have to be in any particular form, even when the stipulation is for the third person an act of liberality or generosity on the part of the promissor or promise, and it need not be made expressly and formally. Revocation of Stipulation Pour Autrui • • • Stipulation Pour Autrui can be revoked prior to its acceptance by the third person beneficiary. After acceptance, however, the stipulation may no longer be revoked because the third party in now entitled to demand for its fulfillment. The word revoked as used in Article 1311 must be understood to imply revocation by the mutual consent of the contracting parties, or at least by direction of the party to whom the promise was made. Page | 118 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Rights of the Parties • Third party beneficiary may demand for the fulfillment of the stipulation in his favor provided that he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. Exception: Under Article 1314, any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. Interference with Contractual relations • Contracts Creating Real Rights • Third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby, subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. Example: registered real estate mortgage contract. • • • Mortgage is a real right, which follows the party, even after subsequent transfers by the mortgagor. The sale or transfer of the mortgaged property cannot affect or release the mortgage; thus, the purchaser or transferee is necessarily bound to acknowledge and respect the encumbrance. Under Article 2129, the mortgage on the property may still be foreclosed despite the transfer. Contracts in Fraud of Creditor Creditors, in order to satisfy their claims, may: 1. Pursue properties in the possession of the debtor. 2. Exercise all the rights and bring all the actions of the debtor, except those purely personal to such debtor. 3. Impugn the acts which the debtor may have done to defraud them. One becomes liable in an action for damages for a nontrespassory invasion of another’s interest in the private use and enjoyment of asset if: a. The other has property rights and privileges with respect to the use or enjoyment interfered with. b. The invasion is substantial c. The defendant’s conduct us a legal cause of the invasion. d. The invasion is either intentional and unreasonable or unintentional and actionable under general negligence rules. In order that an action against a third person for contractual interference can be maintained, the following elements must be present: 1. Existence of a valid contract. 2. Knowledge on the part of the third person of the existence of the contract. 3. Interference of the third person without legal justification or excuse. • • Principle of Tort Interference General Rule: the obligation of contracts is limited to the parties making them and, ordinarily, only those who are parties to contracts are liable for their breach. Penalized because it violates the property right of a party in a contract to rea the benefits that should result therefrom. A third person may be held liable only when there is no legal justification or excuse for his action or when his conduct is stirred by a wrongful motive. To sustain a case for tortuous interference, the interferer must have acted with malice or must have been driven by purely impious reasons to injure the plaintiff. Gilchrist vs Cuddy • • A person is not a malicious interferer if his conduct is impelled by a proper business interest. A financial or profit motivation will not necessarily make a person an officious Page | 119 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • interferer liable for damages as long as there is no malice or bad faith involved. A third person can be held liable for tortuous interference with contractual relations even if he does not know the identity of one of the contracting parties. Note: • An offer that is not accepted, either expressly or impliedly, precludes the existence of consent, which is one of the essential elements of a contract. Article 1315. Contracts are perfected by mere consent, and from that moment the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law. (1258) Consent Article 1316. Real contracts, such as deposit, pledge and commodatum, are not perfected until the delivery of the object of the obligation. (n) • • • Perfection of Contracts Is manifested by the meeting of the offer and acceptance upon the thing which are to constitute a contract. Once there is concurrence of the offer and acceptance of the object and cause, the stage of negotiation is finished. Until the contract is perfected, it cannot, as an independent source of obligation, serve as a binding juridical relation. Hence, the negotiation stage does not, as a general rule, grant one of the parties the cause of action to recover damages from the other. Stages of Contracts A contract undergoes three distinct stages: 1. Negotiation or preparation. 2. Perfection 3. Consummation Negotiation or preparation • Begins when the prospective contracting parties manifest their interest in the contract and ends at the moment of their agreement. Exception: when the parties entered into a contract of option, which is defined as a preparatory contract in which one party grants to the other, for a fixed period and under specified conditions, the power to decide, whether or not to enter into a principal contract. • • Perfection or birth of the contract • Occurs when they agree upon the essential elements thereof. Consummation • Occurs when the parties fulfill or perform the terms agreed upon in the contract, culminating in the extinguishment thereof. When the contract of option is deemed perfected, it would be a breach of that contract to withdraw the offer during the agreed period. If the optioner-offeror withdraws the offer before its acceptance (exercise of the option) by the optionee-offeree, the latter may not sue for specific performance on the proposed contract (“object” of the option) since it has failed to reach its own stage of performance. Perfection of Contracts • • The perfection of the contract takes place upon the concurrence of the essential elements thereof. A contract which is consensual as to perfection is so established upon a mere meeting of minds, i.e., the concurrence of the offer and acceptance, on the object and on the cause thereof. Page | 120 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • A contract which requires the delivery of the object of the agreement, as in a pledge or commodatum, is commonly referred to as a real contract. 4 contracts which are classified as real which can only be perfected by the delivery of the object of the contract: 1. 2. 3. 4. Deposit Pledge Commodatum Mutuum • Other than these four contracts, all other contracts are consensual and perfected by mere consent. • matter, read into it any other intention that would contradict its plain import. Courts have no power to relieve parties from obligations voluntarily assumed, simply because their contracts turned out to be disastrous deals or unwise investments. Article 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. (1259a) Example: Unauthorized Contracts Sale is a consensual contract and is perfected by mere consent, which is manifested by a meeting of the minds as to the offer and acceptance thereof on the subject matter, price and terms of payment of the price. • • Obligatory Force of Contracts • • • • • • Obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the parties and should be complied with un good faith. In characterizing the contract as having the force of law between the parties, the law stresses the obligatory nature of a binding and valid agreement. A contract becomes obligatory upon its perfection. Once a contract is entered into, no party can renounce it unilaterally or without the consent of the other. It is a general principle of law that no one may be permitted to change his mind or disavow and go back upon his own acts, or to proceed contrary thereto, to the prejudice of the other party. When couched in clear and plain language, contracts should be applied according to their literal tenor and that courts cannot supply material stipulations, read into the contract words it does not contain or, for that A contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. However, a contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation is not void but merely unenforceable. Bumanlag vs Alzate • • No consent is given by the alleged principal in unauthorized contracts entered into by an alleged agent, the same is declared merely unenforceable (not void) by Article 1317 and 1403, par. 1 of the Civil Code. In declaring the contract to be merely unenforceable, the law allows the defect of the contract to be cured by ratification. Basis: unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. CHAPTER 2 Essential Requisites of Contracts General Provisions Page | 121 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1318. There is no contract unless the following requisites concur: (1) Consent of the contracting parties; (1) Consent of the contracting parties; (2) Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; (2) Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; (3) Cause of the obligation which is established. (3) Cause of the obligation which is established. (1261) • The foregoing requisites are applicable only to consensual contracts, or those that are perfected by mere consent. Essential Requisites of Contracts Real Contracts Kinds of Elements 1. Essential Elements • Are those necessary for the very existence of the contract itself. • The absence of any one of these essential elements will prevent the creation or existence of a contract. • (1) Consent of the contracting parties; (2) Object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; 2. Natural Elements • Are not essential to the existence of a contract but they are presumed to exist in certain contracts unless there is an express stipulation to the contrary. Example: warranty in case of eviction in a contract of sale. 3. Accidental Elements • Can only exist when the parties expressly provide for them. • These are the clauses, terms, and conditions that the parties may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. In addition to the foregoing, the delivery of the object of the contract is required as a further requisite. (3) Cause of the obligation which is established. (4) delivery of the object of the contract. Purpose of Essential Requisites • • Requisites are necessary only for giving birth to a contract. The requisites enumerated in Article 1318 re necessary only for the perfection of the contract not for its validity. Basis: there is no contract unless the following requisites concur xxx. Note: Essential Requisites • • • The essential requisites or elements are those necessary for the very existence of the contract itself. There is no contract in the absence of these requisites. • Contracts are obligatory upon its perfection, regardless of the form they may have been entered into, the rule is not absolute. The fact that a contract is perfected does not automatically mean that such contract is valid. Page | 122 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Inexistent Contract (Art. 1409) • Is a contract where one or some or all of the essential requisites are both present, i.e., a contract which is absolute simulated, or a contract whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction. Void Contract • Contains all the essential requisites but its cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy, or it is expressly prohibited by law. The following perfected contracts, for example, are void ab initio: 1. A contract that is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. 2. A contract that violates the principle of mutuality of contracts. 3. Solemn contracts that fail to follow the formal requirements of the law for their validity. SECTION 1 Consent Article 1319. Consent is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The offer must be certain and the acceptance absolute. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. perfected; therefore, there is no contract to speak of. Obligations derived from quasi-contracts Referred to as contracts implied in law in the common law system, there is no true contract because of the absence of mutual assent on the part of the parties. Is a juridical relation which arises out of a unilateral act and which relation is imposed by law, though one of the parties thereto does not intend to assume an obligation, for the purpose of avoiding unjust enrichment by that party at the expense of another. • • Element of Consent • • Consent is the essence of the contract. There can be no contract in the true sense in the absence of the element of agreement, or of mutual assent of the parties. Where there is no consent given by one party in a purported contract, such contract is not Always a product of bilateral acts. Manifestation of Consent Acceptance made by letter or telegram does not bind the offerer except from the time it came to his knowledge. The contract, in such a case, is presumed to have been entered into in the place where the offer was made. (1262a) • • Obligations derived from contracts The source of the obligation is the intention of the parties, whether such intention is manifested expressly or impliedly. Consent is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The essence of consent is the conformity of the parties to the terms of the contract, the acceptance by one of the offers made by the other; it is the concurrence of the minds of the parties on the object and the cause which shall constitute the contract. Once there is a concurrence between the offer and the acceptance upon the subject matter (object) and the consideration, a contract is already produced. Mutual consent being a state of mind, its existence may only be inferred from the confluence of two acts of the parties: Page | 123 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. An offer certain as to the object of the contract and its consideration, and 2. An acceptance of the offer which is absolute in that it refers to the exact object and consideration embodied in said offer. Objective theory of Contracts • • The intention of the parties to enter into a contract is to be judged by their outward or objective manifestations of intent. Under American jurisprudence, mutual assent is judged by an objective standard, looking to the express words of the parties used in the contract. Under this contract, understandings and beliefs are effective only if shared. Note: in determining whether a contract is already formed between the parties, the objective manifestations of the intent of parties are to be considered, that is, what a reasonably prudent person would be led to believe from the actions and words of the parties. Computer Network, LTD vs Purcell Tire & Rubber Co. • • • The objective theory lays stress on the outward manifestation of assent made to the other party in contrast to the older idea that a contract was a true meeting of the minds. The intent with which we are concerned is the objective manifestation of intent by the parties, that is, what a reasonably prudent person would be led to believe from the actions and words of the parties. The essentials to formation of a contract may not be found or determined on the undisclosed assumption or secret surmise of either party but must be gathered from the intention of the parties as expressed or manifested by their words or acts. Article 1320. An acceptance may be express or implied. (n) Article 1321. The person making the offer may fix the time, place, and manner of acceptance, all of which must be complied with. (n) Article 1322. An offer made through an agent is accepted from the time acceptance is communicated to him. (n) Article 1323. An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before acceptance is conveyed. (n) Article 1324. When the offerer has allowed the offeree a certain period to accept, the offer may be withdrawn at any time before acceptance by communicating such withdrawal, except when the option is founded upon a consideration, as something paid or promised. (n) Article 1325. Unless it appears otherwise, business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. (n) Article 1326. Advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals, and the advertiser is not bound to accept the highest or lowest bidder, unless the contrary appears. (n) Offer Meeting of Offer and Acceptance The existence of mutual consent, being a state of mind, may only be inferred from the confluence of two acts of the parties: 1. An offer certain as to the object of the contract and its consideration. 2. An acceptance of the offer which is absolute in that it refers to the exact object and consideration embodied in said offer. • The meeting of the minds referred to in Article 1305 is actually the meeting of the offer and the acceptance. Concepts of Offer Negotiation – the initial stage in the life of a contract, is formally initiated by an offer. Page | 124 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Offer • • An expression of willingness to contract on certain terms, made with the intention that it shall become binding as soon as it is accepted by the person to whom it is addressed. Refers to a unilateral proposition which one party makes to the other for the celebration of the contract. • Note: the party who makes the offer is called the offeror while the party to whom an offer is made is called the offeree. by the mere acceptance of the offer without any further act on the part of the offeror. In the event that the terms of the offer is not sufficiently detailed or in the expression of intent is too vague in such a way that the terms thereof cannot be ascertained with reasonably certainty, a contract is not formed notwithstanding the acceptance of the offer and the court is powerless to supply the missing terms, except when the missing terms are minor or insignificant and the parties have clearly manifested an intent to form a contract. Communication of Offer Requisites of Offer 1. The offeror must have a serious intention to become bound by his offer. 2. The terms must be reasonably certain, definite and complete, so that the [arties and the court can ascertain the terms of the offer. 3. The offer must be communicated by the offer to the offeree, resulting in the offeree’s knowledge of the offer. • • • Seriousness of the Offer • For an effective offer to exist, it is a requirement that there must be a serious intent on the part of the offeror in making the offer. Leonard vs Pepsico, Inc. Following the objective theory, the seriousness of such intention is to be determined by what a reasonable person in the offeree’s position would conclude the offeror’s words and actions meant and not by the subjective intentions or beliefs of the offeror. Certainty of Offer • • An offer to be effective must be certain and definite with respect to the cause or consideration and object of the proposed contract. There is an offer in the context of Article 1319 only if the contract can come into existence The offeror cannot accept an offer which has not been communicated to him; and, therefore, as a general rule, an uncommunicated offer, whether by words or acts, cannot result in a contract. An offer that has not been communicated by the offeree, either in words or in actions, is considered as not have been made. There is in fact no need on the part of the offeror to revoke such uncommunicated offer as revocation is necessary only if the offer has been previously communicated to the offeree. Example: “A” wrote a letter addressed to “B” to convey his intention of selling his car to the latter who, by the way, is his officemate. After writing the letter, “A” kept and did the same inside his drawer in the office. After writing the letter, “A” kept and hid the same inside his drawer in the office. By incident, “B” was able to see the letter when he opened A’s drawer. Upon seeing the letter, he wrote his acceptance in the same instrument. In this situation, no contract of purchase and sale is formed between the two since there is no offer which can be subjected to acceptance. Mere Invitations to Make an Offer • A mere statement of willingness to enter into a negotiation or a mere inquiry as to whether a person could make specified articles is not an offer. Page | 125 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • An offer to be effective it must be one which is intended of itself to create legal relations on acceptance, and must be capable of creating a definite obligation. Rosenstock vs Burke • • The word “entertain” applied to an act does not mean the resolution to perform said act, but simply a position to deliberate for deciding to perform or not to perform said act. It was but a mere invitation to a proposal being made to him, which might be accepted by him or not. • Are treated as not offers to contract but as invitations to negotiate. Article 1325. Unless it appears otherwise, business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. Example: Luis came across an advertisement in the Philippine Daily Inquirer about the rush sale of three slightly used Toyota cars for only 200,000 pesos each. Finding the price to be very cheap and in order to be sure that he gets one unit ahead of the others, Luis immediately phoned the advertiser “Summit, Inc.” and placed an order for one car. In this situation, Luis may not sue the company for any breach as no contract is formed between them. Preliminary Negotiation • • • Are not viewed as an offer but rather are invitations to negotiate or to make an offer. It only expresses a willingness to discuss of possibility of entering into a contract. In determining whether there is an offer to contract or only preliminary negotiations for contract, only direct language indicating intent to defer formation of contract, and definiteness or indefiniteness of words used in opening negotiation, as well as business usages and all accompanying circumstances, must be considered. Invitation to treat (or invitation to bargain) • • An invitation to treat may be seen as a request for expressions of interest. The following are examples of invitation to treats (or simply invitations to make an offer): A. Advertisement of Things for Sale The clause “unless it appears otherwise” takes into consideration the fact that advertisement may, under certain situation, be in the nature of an offer. Carlill vs Carbolic Smoke Ball Company • • Is an action by one party which may appear to be a contractual offer but which is actually inviting others to make an offer of their own. Note: the distinction is important because if a legitimate contractual offer is accepted by another, a binding contract is immediately formed and the terms of the original offer cannot be further negotiated without both parties’ consent. • Purpose: the law seeks to avoid such fairness by treating advertisements of things for sale merely as invitations to make an offer. • The advertisement was an offer of unilateral contract between the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company and anyone who satisfies the conditions set out in the advertisement. Weight was placed on the £1000 bank deposit that claimed to show their sincerity in the matter in showing that the advertisement was not just a puff. Whether or not a business circular, a corporate prospectus, a published price list, or other advertisement of like nature is an offer which will, on acceptance form a contract, or is merely an invitation to make an offer, depends on the language used; but generally a newspaper advertisement or circular couched in general language and proper to be sent to all persons interested in a particular trade or business, or a prospectus of a general and descriptive Page | 126 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 nature, will be construed as an invitation to make an offer. hammer has fallen The seller has the obligation of notifying those attending the auction that sales of goods made during the auction are not final until confirmed by the seller. B. Invitations to Bid • Where a person or a corporation advertises for or requests bidders for property to be sold or for the erection or construction of particular work, it is well-settled that this is simply an invitation to make offer, to make tenders, as it is often called, and is not an offer obliging the one extending the invitation to accept the highest or lowest of any of the bids; and this rule applies although the call for bids reserves no right to reject any and all bids; unless it contains language subject to the interpretation that the intention is to let the contract to the highest or lowest bidder. D. Display of Goods • Basis: Article 1326 of the Civil Code of the Philippines. • Fisher vs Bell The bid proposals or quotations submitted by the prospective suppliers are the offers and the reply of the prosper, the acceptance or rejection of the offers. • • • C. Auctions • The display of goods with a price ticket attached in a shop window or on a supermarket shelf is not an offer to sell but an invitation for customers to make an offer to buy. The bid proposal submitted by the bidder is the offer, which the auctioneer can accept or reject as he chooses. The sale is considered perfected only when the auctioneer announces its perfection by the fall of the hammer, or in other customary manner. • • Where goods are displayed in a shop together with the price label, such display is treated as an invitation to treat (invitation to make an offer) by the seller, and not an offer. The offer is instead made when the customer presents the item to the cashier together with the payment. Acceptance occurs at the point the cashier takes payment. This means that if a shop mistakenly displays a good for sale at a very low price it is not obliged to sell it for that amount. Termination of Offer Auction with reserve There is no obligation to sell, and the seller may refuse the highest bid. The seller may reserve the right to conform or reject the sale even after the Auction without reserve The goods may not be withdrawn by the seller and they must be sold to the highest bidder. • • • An offer is terminated either through the action of the parties or by operation of law. The parties can terminate the offer in three ways: by revocation, by rejection, or by counter-offer. Termination of offer by operation of law may occur through the supervening illegality of the proposed contract, lapse of time, destruction of the subject matter of the offer, or death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either the offeror or offeree. Page | 127 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 A. Revocation • • • • • • • • • • • • At any time prior to the perfection of the contract, either negotiating party may stop the negotiation. The offer, at this stage, may be withdrawn or revoked by the offeror, as a rule. The power to revoke is implied in the criterion that no contract exist until the acceptance to the offer is known. Upon the revocation or withdrawal of the offer, the same is considered terminated. The acceptance of an offer must be known to the offeror. The contract is perfected only from the time an acceptance of an offer is made known to the offeror. Unless the offeror knows of the acceptance, there is no meeting of the minds of the parties, no real concurrence of the offer and acceptance. As a rule, the offeror may withdraw its offer and revoke the same before acceptance thereof by the offeree However, where a period is given to the offeree within which to accept the offer and the same has a separate consideration, a contract of option is deemed perfected, and it would be a breach of that contract to withdraw the offer during the agreed period. In contracts between absent persons, the theory holding that an acceptance by letter of an offer has no effect until it comes to the knowledge of the offerer. It means, that before the acceptance is known, the offer can be revoked, it not being necessary, in order for the revocation to have the effect of impeding the perfection to the contract, that it be known by the acceptant. The revocation or withdrawal of the offer is effective immediately after its manifestation, such as by its mailing and not necessarily when the offeree learns of the withdrawal. B. Rejection and Counter-offer • The offer may also be terminated when the person to whom the offer is made (the offeree) either rejects the offer outright or makes a counteroffer of his own. • By rejecting the offer, the offeree thereby terminates the offer and his subsequent attempt to accept the previous offer will not result in its reinstatement. • If the offeree subsequently attempts to accept the offer after its rejection, the same will amount to a new offer on his part and the original offeror (who now becomes the offeree) must accept the new offer in order for a contract to be perfected. Counter-offer • • • A rejection of the original offer and an attempt to end the negotiation between the parties on a different basis. It has dual function: it rejects the original offer and simultaneously makes a new offer. The original offer is therefore terminated and the original offeree now becomes the new offeror. Lapse of Time • • • • Where time in an offer for its acceptance, the offer is terminated at the expiration of the time given for its acceptance. If the offer does not state a specific time period for acceptance, the passage of a reasonable length of time after the offer has been made will likewise result in the termination of the offer. As to what constitute a reasonable time, the same shall depend upon the relevant circumstances and must be decided by the courts on a case-to-case basis. An offer made inter praesentes (or made to a person present) must be accepted immediately when the offeror has not fixed a period for acceptance, otherwise the offer is immediately terminated. Page | 128 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • C. Effect of Death, Insanity, Insolvency, or Civil Interdiction • • If prior thereto, either party dies, suffer from civil interdiction, becomes insane or insolvent, the offer is rendered ineffective. The disappearance of either party or his loss of capacity before perfection prevents the contractual tie from being formed. Reason: • • Villanueva vs Court of Appeals • • The contract is not perfected except by the concurrence of two wills which exist and continue until the moment that they occur. The contract is not yet perfected at any time before acceptance is conveyed; hence, the disappearance of either party or his loss of capacity before perfection prevents the contractual tie from being formed. The insolvency of a bank and the consequent appointment of a receiver restrict the bank’s capacity to act, especially in relation to its property. D. Supervening Illegality and Destruction of Subject Matter • • • The termination of the offer likewise occurs when a legislative enactment or a court decision makes the offer illegal after it has been made. The offer is likewise terminated if the specific subject matter thereof is destroyed before the offer is accepted. If loss or destruction of the determinate thing without the fault of the debtor results in the extinguishment of the obligation to deliver a determinate thing, with more reason that the offer to deliver a specific thing should be considered terminated upon the loss or destruction of the subject matter of the offer to acceptance. Option • • • • • Is a preparatory contract in which one party grants to the other, for a fix period and under a specified condition, the power to decide, whether or not to enter into a principal contract. It binds the party who has given the option, not to enter into the principal contract with any other person during the period designated, and, within that period, to enter into such contract with the one to whom the option was granted, if the latter should decide to use the option. It is a separate agreement distinct from the contract which the parties may enter into upon the consummation of the option. A continuing contract by which the owner stipulates with another that the latter shall have the right to buy the property at a fixed price within a certain time, or under, or in compliance with, certain terms and condition, or which gives to the owner of the property the right to sell or demand a sale. It is sometimes called an unaccepted offer. An option is not of itself a purchase, but merely secures the privilege to buy. It is not a sale of property but a sale of the right to purchase. It is simply a contract by which the owner of the property agrees with another person that he shall have the right to buy his property at a fixed price within certain time. Contract of Sale vs Option Option An unaccepted offer. State the terms and conditions on which the owner is willing to sell the property, if the optionee elects to accept them within the time limited. If the optionee does so elect, he must give notice to the other party, and the accepted offer Contract of Sale Fixes definitely the relative rights and obligations of both parties at the time of its execution. The offer and the acceptance are concurrent, since the minds of the contracting parties Page | 129 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 thereupon becomes meet in the terms of valid and binding the agreement. contract (of sale). If an acceptance is not made within the time fixed, the owner is no longer bound by his offer, and the option is at an end. When Supported by Separate Consideration • • • • Where a period is given to the offeree within which to accept the offer and the same is founded upon or supported by a separate consideration, a contract of “option” is deemed perfected. If the contemplated contract is one of sale, an accepted unilateral promise which specifies the thing to be sold and the price to be paid, when coupled with a valuable consideration distinct and separate from the price, is what may properly be termed a perfected contract of option. For an option contract to be valid and enforceable against the promisor, there must be a separate and distinct consideration that supports it. When the option becomes a contract, the offeror is bound by the agreement and may not withdraw the offer during the period agreed upon. If the right to withdraw whimsically/arbitrarily • • Article 19 of the Civil Code will apply. It provides that every person must, in the exercise of his right and in the performance of his duties, act with justice, give everyone his due, and observe honesty and good faith. Sanchez vs Rigos • Even if the option is not a contract in the absence of a cause or consideration, in which case the promisor is not bound by his promise and may, accordingly, withdraw it, nonetheless, pending notice of its withdrawal, his accepted promise partakes, however, of the nature of an offer which, if accepted, results in a perfected contract. Consideration in Option Contract • • • If the period is not itself founded upon or supported by a consideration, the option does not become a contract. The offeror is still free and has the right to withdraw the offer before its acceptance, or, if an acceptance has been made, before the offeror’s coming to know of such fact, by communicating that withdrawal to the offeree. exercised Reason: An offer implies an obligation on the part of the offeror to maintain in such length of time as to permit the offeree to decide whether to accept or not, and therefore cannot arbitrarily revoke the offer without being liable for damages which the offeree may suffer. When not Supported by Separate Consideration • was • • The contract of option must be supported by a consideration. The consideration supporting the option, must be distinct and separate from the consideration of the projected principal or main contract (subject matter of the option). The same is an onerous contract for which the consideration must be something of value, although its kind may vary. If the consideration is not monetary, these must be things or undertakings of value, in view of the onerous nature of the contract option. ‘ When a consideration for an option contract is not monetary, said consideration must be clearly specified as such in the option contract or sale. Page | 130 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • Note: • The provision in Article 1354 that the existence of consideration is to be presumed in a contract does not apply to the contract of option or to “accepted unilateral promise to buy or sell.” Option Money Distinguished Money • from Earnest Earnest money is something of value to show that the buyer was really in earnest, and given to the seller to bind the bargain, and whenever earnest money is given in a contract of sale, it is considered as part of the purchase price and proof of the perfection of the contract. Option Money A money given as a distinct consideration for an option contract. While option money applies to a sale not yet perfected. When the would-be buyer gives the option money, he is not required to buy. • Earnest Money Is part of the purchase price. Given only where there is already a sale. When it is given, the buyer is bound to pay the balance. Effect of Qualified Acceptance Qualified Acceptance – involves a new proposal constitutes a counter-offer and rejection of the original offer. Counter-offer – a rejection of the original offer and an attempt to end the negotiation between the parties on a different basis. • • Acceptance of Offer Requirement of Acceptance Acceptance • • • • The offeree’s expression of assent to the exact terms of the offer. To produce a contract, there must be acceptance, which may be express or implied, but must not qualify the terms of the offer. An acceptance concludes the making of a contract; nothing further is required. The effect of an unqualified acceptance of the offer is to perfect a contract. Acceptance must be absolute An acceptance is considered absolute and unqualified when it is identical in all respects with that of the offer so as to produce consent or a meeting of the minds. There is no acceptance sufficient to produce consent, when a condition in the offer is removed, or a pure offer is accepted with a condition, or when term is established, or changed, in the acceptance, or when a simple obligation is converted by the acceptance into an alternative one. When something is desired which is not exactly what is proposed in the offer, such acceptance is not sufficient to generate consent because any modification or variation from the terms of the offer annuls the offer. A proposal to accept or an acceptance, introducing new conditions or terms varying from those offered amounts to a rejection of the offer and the submission of a counterproposal and puts an end to the negotiations without forming a contract unless the party making the offer renews it or agrees to the suggested modifications. Mirror-Image Rule • • • • Requires the offeree’s acceptance to exactly match the offeror’s offer – to mirror the offer. In effect, the acceptance must be the mirror image of the offer. It has been ruled in this jurisdiction that the acceptance must be identical in all respects with that of the offer so as to produce consent or meeting of the minds. When something is desired which is not exactly what is proposed in the offer, such acceptance is not sufficient to generate Page | 131 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 consent because any modification or variation from the terms of the offer annuls the offer. the price and as proof of the perfection of the contract. Manner and Form of Acceptance Limketkai Sons Millings, Inc. vs Court of Appeals Manner of Acceptance • • When any of the elements of the contract is modified upon acceptance, such alteration amounts to a counter-offer. The request for change made by the offeree concerns the amount and manner of payment of the price, which is an essential element in the formation of a binding and enforceable contract of sale. • Villanueva vs Philippine National Bank • • • An acceptance of an offer which agrees on the rate of the payment but varies the term is ineffective. An acceptance may contain a request for certain changes in the terms of the offer and yet be a binding acceptance so long as it is clear that the meaning of the acceptance is positively and unequivocally to accept the offer, whether such request is granted or not. The acceptance of the offer was qualified, which amounts to a rejection of the original offer. Villonco Realty Company vs Bormaheco, Inc. • • • • Where the alleged changes made in the acceptance are not material but merely clarificatory made in the acceptance of what had previously been agreed upon, then there is no rejection of the original offer. Even if a letter accepting an offer enumerates certain basic terms and conditions are prescriptions on how the obligation is to be performed and implemented and not conditions for the perfection of the contract, the same is not a counter-offer. The controlling fact is that there was agreement between the parties on the subject matter, the price and the mode of payment and that part of the price was made. Whenever earnest money is given in a contract of sale, it shall be considered part of • • • • The offeror has a right to prescribe in his offer the time, place, and manner of acceptance or other matters which it may please him to insert in and make a part thereof, and the acceptance, to conclude the agreement, must in every respect meet and correspond with the offer, neither falling short of, nor going beyond, the terms propose, but exactly meeting them at all points and closing with them just as they stand, and, in the absence of such an acceptance subsequent words or acts of the parties cannot create a contract. The acceptance must not vary terms of the offer, when the offeror fixes the time, place and manner of acceptance, the offeree must comply with the same and no contract is formed unless the latter uses that specified mode or manner of acceptance. An attempt on the part of the offeree to accept the offer in a different manner does not bind offeror as the absence of the meeting of the minds on the altered type of acceptance. If the parties intended that there should be an express acceptance, the contract will be perfected only upon knowledge by the offeror of the express acceptance by the offeree of the offer. An acceptance which is not made in the manner prescribed by the offeror is not effective but constitutes a counter-offer which the offeror may accept or reject. Forms of Acceptance • • An acceptance may be express or implied, unless the law specifically requires a particular or manner of expressing such consent. The rule is that except where a formal acceptance is so required, although the acceptance must be affirmatively and clearly made and must be evidenced by some acts Page | 132 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • or conduct communicated to the offeror, it may be made either in a formal or informal manner, and may be shown by acts, conduct, or words of the accepting party that clearly manifest a present intention or determination to accept the offer. If the parties intended that there should be an express acceptance, the contract will be perfected only upon knowledge by the offeror of the express acceptance by the offeree of the offer. Note: • • • Acceptance Through Agent • If an offer has been made through an agent, it is deemed accepted from the time acceptance is communicated to said agent, since by legal fiction, the agent is the extension of the personality of the principal. When acceptance binds offeror: Theory of Cognition • The acceptance may be made through the medium of letters, telegrams, or telephonic communications, and result in a complete contract as soon as an offer thus made is unconditionally accepted, unless the offeror fixes a different mode of acceptance pursuant to Article 1321. With regard to the contracts between absent person or when the parties involved are not dealing face-toface, there are two principal theories as to when the contract is perfected: 1. Theory of Cognition • An acceptance by letter of an offer has no effect until it comes to the knowledge of the offeror. • Being followed under the Spanish Civil Code. 2. Mailbox Rule • An acceptance by letter of an offer is effective form the time the latter is sent. • Also called the deposited acceptance rule, which majority of the courts of the United States of America uphold. • Unless the offeror knows of the acceptance, there is no meeting of the minds of the parties, no real concurrence of offer and acceptance. The contract is perfected only from the time an acceptance of an offer is made known to the offeror. Before the acceptance is known, the offer can be revoked, it not being necessary, in order for the revocation to have the effect of impeding the perfection of the contract, that it be known by the acceptant. The offeree may still revoke his acceptance before it comes to the knowledge of the offeror (Dr. Tolentino) Jardine Davies, Inc. vs Court of Appeals • For the contract to arise, the acceptance must be made known to the offeror. Accordingly, the acceptance can be withdrawn or revoked before it is made known to the offeror. Article 1327. The following cannot give consent to a contract: (1) Unemancipated minors; (2) Insane or demented persons, and deaf-mutes who do not know how to write. (1263a) Article 1328. Contracts entered into during a lucid interval are valid. Contracts agreed to in a state of drunkenness or during a hypnotic spell are voidable. (n) Article 1329. The incapacity declared in article 1327 is subject to the modifications determined by law, and is understood to be without prejudice to special disqualifications established in the laws. (1264) Page | 133 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Capacity to Give Consent Importance of Capacity • • • The legal capacity of the parties is an essential element for the existence of the contract because it is an indispensable condition for the existence of consent. Legal consent presupposes capacity. For consent to be valid it must be given only by a person with legal capacity to give consent. The following are the persons who cannot give valid consent to contract: (1) Unemancipated minors; (2) Insane or demented persons, and deafmutes who do not know how to write. • • • If said persons give consent to a contract, the consent is not considered lacking or nonexistent, which will make the contract inexistent. Instead, the consent thus given is considered merely as defective. Thus, the contract is only classified as unenforceable if both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract, or voidable of only one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract. Person Not Legally Capacitated to Contract • The burden of proof is on the individual asserting a lack of capacity to contract, and this burden has been characterized as requiring for its satisfaction clear and convincing evidence. Persons who are incapable of giving consent to a contract: 1. Unemancipated minor. 2. Insane or demented person. 3. Deaf-mute who do not know how to write. Note: the Rules of Court also provide for the guardianship of persons considered incompetent, including persons suffering from the penalty of civil interdiction or who are hospitalized lepers, prodigals, deaf and dumb who are unable to read and write, those who are of unsound mind, even though they have lucid intervals, and persons not being of unsound mind, but by reason of age, disease, weak mind, and other similar causes, cannot, without aid, take care of themselves and manage their property, becoming thereby an easy prey for deceit and exploitation. Special Disqualification Incapacities • Are limitations on capacity to act and are, therefore, restrictions on the exercise of the right, and are founded on subjective circumstances within the person afflicted thereof; whereas, disqualifications or prohibitions are not limitations on capacity to act but merely restrictions on the enjoyment of the right and are based on reasons of morality. The following are examples of prohibitions or special disqualifications: 1. The spouses and persons living together as husband and wife without a valid marriage are prohibited from making donations to each other. Any such donation, whether direct or indirect, is void. 2. The spouses cannot sell to each other, except when the property regime is complete separation. Any such sale is void. 3. The guardian cannot acquire by purchase, even at a public or judicial action, the property of the ward; otherwise, the sale is void. 4. The agent cannot acquire by purchase, even at a public or judicial action, the property whose administration or sale has been trusted to him, unless the consent of the principal has been given; otherwise, the sale is void. 5. The executor or administrator cannot acquire by purchase, even at a public or judicial action, the property of the estate under his administration; otherwise the sale is void. Page | 134 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 6. Public officers and employees cannot acquire by purchase even at public or judicial action, the property of the State or of any subdivision thereof or of any governmentowned or controlled corporation or institution, the administration of which has been entrusted to them; otherwise, the sale is void. 7. Justices, judges, prosecuting attorneys, clerks of superior and inferior courts, and other officers and employees connected with the administration of justice, including attorneys or lawyers, cannot acquire by purchase, even at a public or judicial action, the property and rights in litigation or levied upon an execution before the court within whose jurisdiction or territory they exercise their respective jurisdiction; otherwise, the sale is void. Mercado vs Espiritu • Minor’s right to annul the contract he entered into during minority if he was guilty of mirepresenting his age. When the minor’s physical development could mislead the other party into believing that he was of age, the minor is said to be guilty of estoppel and may not annul the contract on the ground of minority. • Bragaza vs Villa • • Minors Minority • • • • • • The state of a person who is under the age of legal majority and a minor is a person below 18 years of age since majority commences upon attaining the age of 18 years. All minors now are necessarily unemancipated because, under current laws, emancipation can only take place by the attainment of majority age. A contract entered into by a minor is not void, but merely voidable. The law gives the minor the right to annul the contract entered into by him upon his attainment of the age of majority, but he must bring the action for annulment within four years from his attainment of the age of majority, otherwise, the action will be barred by the statute of limitations or prosecution. He may, however, ratify the voidable contract upon reaching the age of majority. He may, however, be represented in a contract by his guardian. • The Mercado ruling applies only if the minor is guilty of active mirepresentation, such as when the document signed by the minor specifically stated he was of age. If the minor is guilty only of passive or constructive mirepresentation, such as when he simply failed to disclose his minority in the document that he signed, the minor can still annul the contract on the ground of minority. The Mercado ruling was also held inapplicable in a case where the minor did not pretend to be of age at the time the contract was made and his minority was well known to the other party, hence, the contract may still be annulled. Insane or Demented • • • The law presumes that every person is of sound mind, in the absence of proof to the contrary. Since contractual capacity is determined at the time of the perfection of the contract, the burden of proving that a party is mentally incapacitated at the time of the execution of the contract rest upon him who alleges it; if no sufficient proof to this effect is presented, such capacity must be presumed. If a contracting party is under guardianship by reason of insanity, there is naturally a presumption of insanity. Note: contract entered into during a lucid interval are valid. Page | 135 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Lucid Interval • • Intervals occurring in the metal life of an insane person during which he is completely restored to the use of his reason, or so far restored that he has sufficient intelligence, judgement, and will to enter into contractual relations, or perform other legal acts, without disqualification by reason of his disease. If a contracting party is under guardianship by reason of insanity, the burden of proof that the contract is entered into during a lucid interval is upon him who upholds the validity of the contract. • As to other illiterates, they are presumed to have the capacity to give consent to a contract but the law imposes an obligation upon the other contracting party to fully explain the contract to them. Old Age or Other Physical Infirmities General Rule: In the same manner, a person is not incapacitated to enter into a contract merely because of advanced years or by reason of physical infirmities. Exception: Note: not every kind of insanity, will annul consent. • A person under guardianship for insanity may still enter into a valid contract and even convey property, if his menta defect did not interfere with or affect his capacity to appreciate the meaning and significance of the transaction entered into by him. When such age or infirmities impair his mental faculties to the extent that he is unable to properly, intelligently and fairly understand the provisions of said contract, or to such extent as to prevent him from properly, intelligently, and fairly protecting his property rights, is he considered incapacitated. Standard Oil Company of New York vs Arenas • Civil Interdiction The Court did not annul a bond executed by a person suffering from monomania of great wealth because it was not shown that the reason for its execution was an ostentation of wealth and that such was purely an effect of monomania of wealth. • • Contracts agreed to in a state of drunkenness or during a hypnotic spell are voidable. • In order for these persons to be considered incapable of giving consent, it is necessary that such state must have interfered with the person’s mental faculties in such a way that it prevented him form knowing the meaning and significance of the transaction entered by him. Illiteracy, Old Age, and Civil Interdiction Illiteracy • Is not an incapacity to give consent, except when he is also a deaf-mute. An accessory penalty imposed upon an accused who is sentenced to a principal penalty not lower than reclusion temporal. It deprives the offender during the time of his sentence of the following rights: o Parental authority, or guardianship, either as to the person or property of any ward; o Marital authority o Management of his property o Disposition of his property by any act or any conveyance inter vivos. Article 1330. A contract where consent is given through mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud is voidable. (1265a) Vices of Consent • To create a valid contract, the meeting of the minds must be free, voluntary, willful and with a reasonable understanding of the various Page | 136 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 obligations the themselves. parties assumed for Consent in contracts presupposes the following requisites: 1. It should be intelligent or with an exact notion of the matter to which it refers. 2. It should be free. 3. It should be spontaneous. • • A contract where consent is given through mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud is voidable. These circumstances are defects of the will, the existence of which impairs the freedom, intelligence, spontaneity and voluntariness of the party in giving consent to the agreement. Article 1331. In order that mistake may invalidate consent, it should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract. Mistake as to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties will vitiate consent only when such identity or qualifications have been the principal cause of the contract. A simple mistake of account shall give rise to its correction. (1266a) Covers Both Mistake and Ignorance Ignorance Mistake The absence of A wrong conception knowledge with about said thing, or respect to a thing. a belief in the existence of some circumstance, fact, or event, which in reality does not exist. Character of Mistake Which Annuls Consent • Not every mistake renders a contract voidable. In order that mistake may invalidate consent, it is necessary that: 1. It should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract, or to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties when the same have been the principal cause of the contract. 2. It must get excusable and not one that could have been avoided by the party alleging it. 3. It must generally be a mistake of fact and not mistake of law. Mistake as to Object of Contract Article 1332. When one of the parties is unable to read, or if the contract is in a language not understood by him, and mistake or fraud is alleged, the person enforcing the contract must show that the terms thereof have been fully explained to the former. (n) Mistake as to the object of the contract (error in re) may either be: 1. Mistake over the identity of the thing (error in corpore) which happens when one thing is mistaken for another. Article 1333. There is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract. (n) Example: substitution of a specific thing contemplated by the parties with another. Article 1334. Mutual error as to the legal effect of an agreement when the real purpose of the parties is frustrated, may vitiate consent. (n) • Mistake 2. Mistake over the essence or the substantial qualities of a thing (error in This kind of mistake destroys the will of the parties and prevents the formation of a juridical act, hence, there is no contract. Page | 137 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • substantia) which affects not the identity of the thing but the materials which compose it. Mistake as to Identity or Qualification of Parties Example: the purchase of an object which is gold plated in the belief that it is really gold. 1. Mistake must be either with regard to the identity or with regard to the qualification of one of the contracting parties. 2. The identity or qualification must have been the principal consideration for the celebration of the contract. The consent here is vitiated and the contract is voidable. This is the kind of mistake referred to in Article 1331 concerning the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract. 3. Mistake over determinate attributes or characteristics of a thing foreign to its matter, but which has been understood as essential by the contracting parties (error in sustantia) Example: A painting by Goya is bought and the painting is not of Goya. • This vitiates consent and the contract is voidable. 4. Mistake is to amount (error in quantitate) which refers to mistake as to the extension or dimension of the object and differs from the mistake of account which is simply a mistake in the computation or in a mathematical operation. • This mistake will vitiate consent and the contract becomes voidable. Mistake as to Conditions Genera Rule: mistake as to condition will invalidate consent only when they are essential, or have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract. Exception: When the conditions are not essential but merely accidental, they will not invalidate consent. Requisites: Roman Catholic Church vs Pante There was no mistake committed by the Church that may invalidate consent because the actual occupancy of a buyer over the land does not appear to be a necessary qualification that the Church requires before it could sell its land in view of the following reasons: 1. The Church sold the same property to the Spouses Rubi when the latter were not also actual occupant of the lot. 2. Given the size of the lot, it could serve no other purpose than as a mere passageway. 3. The Church was aware that Pante was using the lot merely as a passageway. Mistake as to Non-Essential Elements The following kinds of mistake do not vitiate consent because they refer merely to non-essential elements of the contract: 1. Mistake as to the identity or qualification of one of the contracting parties, unless such identity or qualification have been the principal consideration for the celebration of the contract. 2. A simple mistake of account, or mistake in a mathematical operation. The remedy is simply correction. 3. Mistake as to motive because the latter is not an essential element of a contract, unless the motive predetermines the purpose of the contract, in which case it also becomes the cause of the contract. Page | 138 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Mistake must be excusable • • • • • • To invalidate consent, the error must be excusable. It must be real error, and not one that could have been avoided by the party alleging it. The error must arise from facts unknown to him. Article 1333 provides that there is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract. Consequently, an error so patent and obvious that no body could have made it, or one which could have been avoided by ordinary prudence, cannot be invoked by the one who made it in order to annul his consent. A mistake that is caused by manifest negligence cannot invalidate a juridical act. Mistake must be of fact • • • • The provision came into being because a sizeable percentage of the country’s populace was compromised of illiterates, and the documents at the time had been written either in Spanish or English. It is also an accord with our state policy of promoting social justice. It also supplements Article 24 of the Civil Code which calls on the court to be vigilant in the protection of the rights or those who are disadvantaged in life. Note: • • Before Article 1332 may be invoked, it must be convincingly established that the disadvantaged party is unable to read or that the contract involved is written in a language not understood by him. Article 1332 contemplates a situation wherein a contract has been entered into, but the consent of one of the parties is vitiated by mistake or fraud committed by the other contracting party. In order that mistake may be invalidated consent, the same should refer to a mistake of fact and not of law. A mistake of law does not vitiate consent because of the rule that ignorance of the law excuses no one from compliance therewith. Article 1335. There is violence when in order to wrest consent, serious or irresistible force is employed. In order for a mistake of law tom invalidate consent under Article 1334, the following requisites must be present: There is intimidation when one of the contracting parties is compelled by a reasonable and wellgrounded fear of an imminent and grave evil upon his person or property, or upon the person or property of his spouse, descendants or ascendants, to give his consent. • 1. The mistake must be with respect to the legal effect of an agreement. 2. It must be mutual. 3. The real purpose of the parties must have been frustrated. Effect if a party is illiterate • When one of the parties is unable to read, or if the contract is in a language not understood by him, and mistake or fraud is alleged, the person enforcing the contract must show that the terms thereof have been fully explained to the former. To determine the degree of intimidation, the age, sex and condition of the person shall be borne in mind. A threat to enforce one's claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. (1267a) Article 1336. Violence or intimidation shall annul the obligation, although it may have been employed by a third person who did not take part in the contract. (1268) Lim vs Court of Appeals Page | 139 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Violence or Intimidation Violence Refers to physical force or compulsion. There is actual infliction of harm. Intimidation Moral force or compulsion. There is merely a threat to inflict harm. Is external and Internal and does generally prevents not prevent the will the will from acting from operating but at all. merely directs it to operate in only one particular manner. In both, the party is deprived of free will and choice. Requisites of Violence 1. The force employed is either serious or irresistible. 2. It must have been the determining cause of consent. • • It is not necessary that the force be always irresistible. Even if the force is not irresistible but it is serious in such a degree that the victim has no other recourse, under the circumstances, but to submit, the consent is also considered vitiated. Requisites of Intimidation De Leon vs Court of Appeals 1. That the intimidation must be the determining cause of the contract, or must have caused the consent to be given. 2. That the threatened act be unjust or unlawful. 3. That the threat be real and serious, there being an evident disproportion between the evil and the resistance which all men can offer, leading to the choice of the contract as the lesser evil. 4. That it produces a reasonable and wellgrounded fear from the fact that the person from whom it comes has the necessary means or ability to inflict the threatened injury. • • In determining the degree of intimidation, the age, sex, and condition of the person shall be borne in mind. A threat to enforce one’s claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. Article 1337. There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. The following circumstances shall be considered: the confidential, family, spiritual and other relations between the parties, or the fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weakness, or was ignorant or in financial distress. (n) Undue Influence • • • There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. Undue influence is any means employed upon a party which, under the circumstances, he could not well resist and which controlled his volition and induced him to give his consent to the contract, which otherwise he would not have entered into. For undue influence to be present, it is necessary that the influence exerted must have so overpowered or subjugated the mind of a contracting party as to destroy his free agency, making him express the will of another rather than his own. Loyola vs Court of Appeals Requisites in order for undue influence to vitiate consent: 1. A person who can be influenced. 2. The fact that the improper influence was exerted. 3. Submission to the overwhelming effect of such unlawful conduct. Page | 140 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 In determining the existence of undue influence, the following circumstances shall be considered: • • • • The confidential Family Spiritual and other relations between the parties The fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weakness, or was ignorant or in financial distress. Article 1344. In order that fraud may make a contract voidable, it should be serious and should not have been employed by both contracting parties. Incidental fraud only obliges the employing it to pay damages. (1270) and • That influence obtained by persuasion, argument, or by appeal to the affections is not prohibited either in law or morals, and is not obnoxious even in court of equity. • Solicitation, importunity, argument, persuasion are not undue influence. Martinez vs HongKong and Shanghai Bank • person Fraud Baez vs Court of Appeals • Article 1343. Misrepresentation made in good faith is not fraudulent but may constitute error. (n) Article 1338. There is fraud when, through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed to. (1269) Article 1339. Failure to disclose facts, when there is a duty to reveal them, as when the parties are bound by confidential relations, constitutes fraud. (n) • Insidious Machination • Article 1342. Misrepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent, unless such misrepresentation has created substantial mistake and the same is mutual. (n) Refers to deceitful scheme or plot with an evil or devious purpose. Deceit • Article 1340. The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. (n) Article 1341. A mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former's special knowledge. (n) Refers to all kind of deception, whether through insidious machination, manipulation, concealment or misrepresentation, that would lead an ordinarily prudent person into error after taking the circumstances into account. Fraud is defined as the deliberate and intentional evasion of the normal fulfillment of obligation, and properly corresponds to malice or bad faith. Fraud may also be present or employed at the time of birth or perfection of a contract. • Exists where the party, with intent to deceive, conceals or omits to state material facts and, by reason of such omission or concealment, the other [arty was induced to give consent that would not otherwise have been given. It must be sufficient to impress or lead an ordinarily prudent person into error, taking into account the circumstances of each case. Kinds of Fraud Dolo Causante or Dolo Incidente or Dolo Fraud Incidental Fraud Referred to in Referred to in Article 1338 Article 1344 Page | 141 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Are those deceptions or mirepresentations of a serious character employed by one party and without which the other party would not have entered into the contract. Determines or is the essential cause of the consent. Are those which are not serious in character and without which the other party would still have entered into the contract. Refers only to some particular or accident of the obligation. The effect is the Only obliges the nullity of the person employing it contract and the to pay damages. indemnification of damages. Serious in character Not serious in character The cause which Are those which a induces the other re not serious in contracting party to character and enter into a contract without which the with the one who other party would employed it, or the still have entered essential cause of into the contract. the consent. Requisites of Fraud that Vitiates Consent 1. It must have been employed by one contracting party upon the other. 2. It must have induced the other party to enter into the contract. 3. It must have been serious. 4. It must have resulted in damage and injury to the party seeking annulment. General Rule: • Mirepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent. Rationale: • There is no reason for making one of the parties suffer for the consequences of the act of a third person in whom the other contracting party may have reposed an imprudent confidence. Exception: The fraud cause by a third person may produce effects and, in some cases, bring about the nullification of the contract. This will happen when the third person causes the fraud in connivance with, or at least with the knowledge, without protest, of the favored contracting party, in which case the latter cannot be considered exempt from the responsibility. Fraud must be dolo causante • • In order that fraud may vitiate consent, it must be the causal (Dolo Causante), inducement to the making of the contract. The fraud must be the determining cause of the contract, or must have cause the consent to be given. Example of Dolo Causante Tongson vs Emergency Pawnshop Bula, Inc. Some of the instances where this Court found the existence of causal fraud include: Employed by one against another • • The fraud which vitiates consent must have employed by one of the contracting parties only and should not have been employed by both of them; otherwise, the contract is not voidable. The fraud must have been employed by a contracting party upon another and not by a third person. 1. When the seller, who had no intention to part with her property, as tricked into believing that what she signed were papers pertinent to her application for the reconstitution of her burned certificate of title, not deed of sale. 2. When the signature of the authorized corporate officer was forged. 3. When the seller was seriously ill, and died a week after signing the deed of sale raising doubts on whether the seller could have Page | 142 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 read, or fully understood, the contents of the documents he signed or of the consequences of his act. the former had the exclusive franchise to soft drink bottling operations. Fraud Must Be Serious Example of Dolo Incidente • Woodhouse vs Halili • Facts: The plaintiff Charles Woodhouse entered into a written agreement with the defendant Fortunato Halili to organize a partnership for the bottling and distribution of soft drinks. However, the partnership did not come into fruition, and the plaintiff filed a complaint in order to execute the partnership. The defendant filed a Counterclaim, alleging that the plaintiff had defrauded him because the latter was not actually the owner of the franchise of a soft drink bottling operation. Thus, defendant sought the nullification of the contract to enter into the partnership. • The fraud must be serious to annul or avoid a contract and render it voidable. The fraud is serious when it is sufficient to impress, or to lead an ordinarily prudent person into error; that which cannot deceive a prudent person cannot be a ground for nullity. In order for the deceit to be considered serious, it is necessary and essential to obtain the consent of the party imputing fraud. To determine whether a person may be sufficiently deceived, the personal conditions and other factual circumstances need be considered. Other Rules on Fraud Rule on Silence and Concealment Held: • Plaintiff did actually represent to defendant that he was the holder of the exclusive franchise. The defendant was made to believe, and he actually believed, that plaintiff had the exclusive franchise. While the representation that plaintiff had the exclusive franchise did not vitiate defendant’s consent to the contract, it was used by the plaintiff to get from defendant a share of 30% of the net profits; in other words, by pretending that he had the exclusive franchise and promising to transfer it to defendant, he obtained the consent of the latter to give him (plaintiff) a big slice in the net profits. This is the dolo incidente defined in Article 1270 of the Spanish Civil Code, because it was used to get the other party’s consent to a big share in the profits, an incidental matter in the agreement. • • The original agreement may not be declared null and void. The plaintiff had been entitled to damages because of the refusal of the defendant to enter into the partnership. However, the plaintiff was also held liable for damages to the defendant for the misrepresentation that • Concealment which the law denounces as fraudulent implies a purpose or design to hide facts which the other party ought to know. Fraudulent concealment presupposes a duty to disclose the truth and that disclosure was not made when opportunity to speak and inform was presented, and that the party to whom the duty of disclosure, as to a material fact was due, was induced thereby to act to his injury. Guihawa vs People • When the seller has knowledge of a material fact which, if communicated to the buyer, would render the sale unacceptable, or at least, substantially less desirable, the nondisclosure of such fact would amount to fraud. Rural Bank of Sta. Maria, Pangasinan vs Court of Appeals • It was ruled that the non-disclosure to the creditor bank of the purchase price in the Page | 143 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • sale of the mortgaged property (between the debtor-mortgagor and the buyer) did not render the Memorandum of Agreement (between the creditor bank and the buyer) voidable on the ground that the bank’s consent was vitiated with fraud. The debtor-mortgagor and the property’s buyer had no duty, and therefore did not act in bad faith, in failing to disclose to the bank the real consideration of the sale between them. Usual Exaggeration in Trade • The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. Songco vs Sellner • • The law allows considerable latitude to seller’s statements or dealer’s talk; and experience teaches that it is exceedingly risky to accept it at its value face. The refusal of the seller to warrant his estimate should have admonished the purchaser that that estimate was put forth as a mere opinion; and we will not now hold the seller to a liability equal to that which would have been created by a warranty, if one had been given. A man who relies upon such an affirmation made by a person whose interest might so readily prompt him to exaggerate the value of his property does so at his peril, and must take the consequences of his own imprudence. Expression of Opinion General Rule: • A mere expression of opinion does not signify fraud. Exception: • When the opinion is made by an expert and the other party relied on the former’s special knowledge. Quantum of Evidence • The Civil Code does not mandate the quantum of evidence required to prove actionable fraud, either for purposes of annulling a contract (dolo causante) or rendering a party liable for damages (dolo incidente). Viloria vs Continental Airlines, Inc. • Mere preponderance of evidence will not suffice in proving fraud. Tankeh vs Philippines • Developmental Bank of the The purpose of annulling a contract on the basis of dolo causante, the standard of proof required is clear and convincing evidence. Clear and Convincing Evidence • • • • • • Derived from American common law. It is less than proof beyond reasonable doubt (for criminal cases) but greater than preponderance of evidence (for civil cases). The degree of believability is higher than that of an ordinary civil case. When fraud is alleged in an ordinary civil case involving contractual relations, an entirely different standard of proof needs to be satisfied. Mere allegations will not suffice to sustain the existence of fraud. The burden of evidence rests on the part of the plaintiff or the party alleging fraud. Article 1345. Simulation of a contract may be absolute or relative. The former takes place when the parties do not intend to be bound at all; the latter, when the parties conceal their true agreement. (n) Article 1346. An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void. A relative simulation, when it does not prejudice a third person and is not intended for any purpose contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public Page | 144 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 policy binds the parties to their real agreement. (n) Simulation of Contracts Simulation • Is the declaration of a fictitious will, deliberately made by agreement of the parties, in order to produce, for the purpose of deception, the appearances of a juridical act which does not exist or is different with that which was really executed. Requisites: 1. An outward declaration of will different from the will of the parties. 2. The false appearance must have been intended by mutual agreement. 3. The purpose is to deceive third person. Absolute Simulation There is a colorable contract but it has no substance as the parties have no intention to be bound by it. The apparent contract is not really desired or intended to produce legal effect or in any way alter the juridical situation of the parties. An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void, and the parties may recover from each other what they may have given under the contract. Relative Simulation The parties conceal their true agreement. The essential requisites of a contract are present and the simulation refers only to content or terms of the contract. Two Juridical Acts: Ostensible Act is the contract that the parties pretend to have executed. Hidden Act is the true agreement between the parties. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 There appears to be a valid contract but there is actually none because the element of consent is lacking because the parties do not actually intend to be bound by the terms of the contract. The most protuberant index of absolute simulation of contract is the complete absence of an attempt in any manner of the part of the ostensible buyer to assert rights of ownership over the subject properties. To determine the enforceability of the actual agreement between the parties, we must discern whether the concealed or hidden act is lawful and the essential requisites of a valid contract are present. SECTION 2 Object of Contracts Article 1347. All things which are not outside the commerce of men, including future things, may be the object of a contract. All rights which are not intransmissible may also be the object of contracts. No contract may be entered into upon future inheritance except in cases expressly authorized by law. All services which are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy may likewise be the object of a contract. (1271a) Article 1348. Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. (1272) Article 1349. The object of every contract must be determinate as to its kind. The fact that the quantity is not determinate shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract, provided it is possible to determine the same, without the need of a new contract between the parties. (1273) Page | 145 Objects of Contracts Object of Obligation It is the prestation or the conduct required to be observed by the debtor (to give, to do, or not to do). Object of Contract It is the subject matter of the prestation, which can either be a thing, right or service. Example: In the sale of a car, the object of the obligation is the delivery of the car (to give) while the object of the contract is the subject matter of the obligation to give, or the thing sold, which is the car. Requisites of Object of Contract 1. 2. 3. 4. It must be within the commerce of men. It must be licit. It must be real or possible It must be determinate or susceptible to determination. The following cannot be the object of contracts: 1. Things which are outside the commerce of men. 2. Rights which are untransmissible. 3. Future inheritance, except in cases expressly authorized by law. 4. Services which are contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. 5. Impossible things or services. 6. Things which are not susceptible to determination as to its kinds. 7. Things which do not have the possibility or potentiality of coming into existence. Must be within Commerce of Men • All things which are not outside the commerce of men, including future things, may be the object of a contract. • Things which are outside the commerce of men cannot become objects of contracts. • Any contract whose object is outside the commerce of men is void. To be considered within the commerce of men, a thing must be: 1. Susceptible of appropriation or of private ownership. 2. Transmissible The following things may not be the object of a contract because they are not susceptible of appropriation, therefore, outside the commerce of men: 1. Properties of public dominion Example: a. Public streets cannot be converted into a flea market and leased to private individuals. b. The submerged lands in the Manila Bay area, which are declared to part of the State’s inalienable natural resources, cannot be alienated to private entity. c. Properties officially declared military reservations become inalienable and outside the commerce of men and may not be the subject of a contract or of a compromise agreement. 2. Sacred things, common things like the air and the sea, and res nullius, as long as they have not been appropriated. Rights which are intransmissible may not also be the object of the contract because they are also considered outside the commerce of men: 1. Purely personal rights (patria potestas or marital authority, the status and capacity of persons, and honorary titles and distinctions) 2. Public offices, inherent attributes of the public authority, and political rights of individuals (ex: right to suffrage) Saura vs Sindico Such rights may not, therefore, be bargained away curtailed with impunity, for they are conferred Page | 146 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 not for individual or private benefit or advantage but for the public good and interest. Must be Licit • To be an object of a contract, the thing or service must not be contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. Example: Any contract which authorizes slavery in any form is not valid because it is contrary to law and public policy. Must have Possibility or Potentiality of Existence In order for a contract to be valid, it is necessary that the object thereof must either be: 1. Existing at the time of the perfection of the contract. 2. Even if not existing at that time, at least, it has the possibility or potentiality of coming into existence. “Future Things” • Anything which is not yet owned or possessed by the obligor at the time of the celebration of the contract, but it may be manufactured, raised or acquired after the perfection of the contract. When the object of the contract is a “future thing,” there are two possibilities: Example: If there is a purchaser who is willing to take his chance in return for a bigger profit and is willing to purchase, for example, “whatever should be caught in the next haul of the fisherman’s net,” the contract is immediately effective and valid. Exceptions: 1. Future inheritance may not be the object of a contract unless it is in the nature of a partition inter vivos made by the decedent. 2. Future property may not be the object of a donation, unless the donation is between the future spouses, in consideration of their marriage, and to take effect after death. Future Inheritance • A contract entered into upon future inheritance is void. • Any property or right not existence or capable of determination at the time of the contract, that a person may in the future acquire by succession (Blas vs Santos) A contract may be classified as a contract upon future inheritance, prohibited under the second paragraph of Article 1347, where the following requisites concur: 1. That the succession has not yet been opened. 2. That the object of the contract forms part of the inheritance 3. That the promisor has, with respect to the object, an expectancy of a right which is purely hereditary in nature. 1. Conditional • • The efficacy of the contract is dependent upon the future existence of the thing. Example: If the sale involves the next year’s harvest from a specific fam, the contract becomes effective only if the harvest will materialize. If the crops failed, the contract does not become effective. • • • 2. Aleatory • • One of the parties bears the risk of the thing never coming into existence. The prohibition on contracts respecting future inheritance admits of an exception, which is the partition inter vivos referred to in Article 1080 of the Civil Code. If the partition is made by an act inter vivos, no formalities a re prescribed by the Article. The partition will of course be effective only after death. It does not necessarily require the formalities of a will for after all it is not the partition that is the mode of acquiring ownership. The partition here is merely the physical determination of the part to be given to each heir. Page | 147 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Donation of Future Property • • • • • • Donations cannot comprehend future property. As being itself a mode of acquiring ownership, donation results in an effective transfer of title over the property from the donor to the donee once the donation is perfected. The law requires that the donor must be the owner of the thing donated at the time of the donation. By “future property” is understood anything which the donor cannot dispose of at the time of the donation. Future property includes all property that belongs to others at the time the donation is made, although it may or may not later belong to the donor. It cannot be donated, because it is not at present his property, and he cannot dispose of it at the moment of making the donation. Note: at the time of donation = perfection of the donation. Exception: The Family Code allows a donation of future property between the future spouses in donation propter nuptias. • The donation of future property referred to is a donation propter nuptias between the future spouses. It must be determinate or Susceptible to determination • • • • The object of a contract, in order to be considered as certain, need not specify such object with absolute certainty. It is enough that the object is determinable in order for it to be considered as certain. In order for the object of the contract to be considered “determinate,” it is not necessary that the same be particularly or physically segregated from all others of the same class. It is sufficient that the object be determinate as to its kind or species. Impossible Things or Services • Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. Basis: impossibilium nulla obligation est (there is no obligation to do impossible things) Impossible Things – one which is not susceptible of coming into existence or outside the commerce of men. Impossible Service – beyond the ordinary power of man or what which is against the law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. Absolute Relative Impossibility Impossibility When nobody can When it cannot be perform it. performed because of the special condition or qualifications of the obligor. Nullifies the Effects shall contract. depend on whether the same is temporary or permanent. • • If temporary, it does not nullify the contract. The impossibility contemplated by Article 1348, as to services, is that of absolute impossibility. SECTION 3 Cause of Contracts Article 1350. In onerous contracts the cause is understood to be, for each contracting party, the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other; in remuneratory ones, the service or benefit which is remunerated; and in contracts of pure beneficence, the mere liberality of the benefactor. (1274) Article 1351. The particular motives of the parties in entering into a contract are different from the cause thereof. (n) Page | 148 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1352. Contracts without cause, or with unlawful cause, produce no effect whatever. The cause is unlawful if it is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. (1275a) Article 1353. The statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void, if it should not be proved that they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. (1276) Article 1354. Although the cause is not stated in the contract, it is presumed that it exists and is lawful, unless the debtor proves the contrary. (1277) Article 1355. Except in cases specified by law, lesion or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract, unless there has been fraud, mistake or undue influence. (n) Cause of Contracts Gonzales vs Trinidad • • • Cause or consideration is the “why of the contracts, the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into the contract. The cause is the immediate, direct and proximate reason which justifies the creation of an obligation through the will of the contracting parties. What is referred to as the cause of the contract is actually the cause of the obligation. Example: In synallagmatic (or bilateral) contract in which each party is bound to provide something to the other party, the cause of the obligation of one party is the expectation of the performance of the obligation of the other. Kinds of Cause Onerous Contracts Remuneratory Contracts The cause is understood to be, for each contracting party, the prestation or promise of thing or service by the other. The cause of the obligation of one party is the expectation of the performance of the obligation of the other. The cause is the service or benefit which is remunerated. Example: In a contract of sale of a piece of land, the cause for the vendor in entering into the contract is to obtain the price. For the vendee, it is the acquisition of the land. Cause It is the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into it. Object It is the subject matter, which can either be a thing, right, or service. A natural obligation is a sufficient consideration for an onerous contract; hence, a debt that has already prescribed is thus a sufficient The consideration is the service or benefit from which the remuneration is given; causa is not liberality in these cases because the contract or conveyance is not made out of pure beneficence, but solvendi animo. It is essential that the service or benefit for which the remuneration is given must not be in the nature of a demandable debt (or legal obligation), otherwise, it will be an Contracts of pure beneficence The cause is the mere liberality of the benefactor. The liberality of the donor is deemed the causa. The contracts are designed solely and exclusively to procure the welfare of the beneficiary, without any intent of producing any Page | 149 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 cause or consideration for a promise. onerous not a remuneratory contract. satisfaction for the donor. Example: when a person undertakes to give a parcel of land to another in recognition of the latter’s act of saving the life of the former in an accident, the contract is remuneratory because the benefit is given for a past service which does not amount to a demandable obligation. The idea of self interest is totally absent on the part of the transferor. DISTINGUISHED FROM MOTIVE Motive- particular reasons of a contracting party which do not affect the other party, and which do not preclude the existence of a different consideration. Any detriment, prejudice, loss, or disadvantage suffered or undertaken by the promise other than to such as he is in time of consent bound to suffer Essential reason for the contract immediate, direct and proximate reason which justifies the creation of an obligation through the will of the contracting parties objective aspect which justifies the creation of the contract and is known to other party • Example: purchase of a thing • constitutes consideration for the purchaser, not the motives which influenced his mind such as: o its usefulness o its perfection o its relation to another. Cause some right, interest, benefit or advantage conferred upon a promissor, to which he is otherwise not lawfully entitiled Motive condition of the mind which incites to action, but includes also the inference as to the existence of such condition, from an external fact of nature to produce such condition • particular reason of a contracting party which does not affect the other party remote reason for entering into a contract subjective aspect and may not be known to the other party As a general rule, motive does not affect the validity or existence of the contract. However, motive may be regarded as causa when it predetermines the purpose of the contract. Liguez vs CA • Expressly excepts from the rule are contracts that are conditioned upon the attainment of the motives of either party. • This happens when: the realization of such motive or particular purpose has been made a condition upon which the contract is made to depend. • it may now affect the validity or existence of the contract. • when motive is unlawful – the contract is NULL and VOID. • if the motive is negated, the contract becomes inexistent. (Liguez vs CA) REQUISITES OF CAUSE Page | 150 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 The ff. are the requisites of cause: 1. It must exist 2. it must be true 3. it must be lawful • EXISTING AND LAWFUL CAUSE • Art 1352 – Contracts without cause, or with unlawful cause produce no effect whatsoever. • Contract without a cause- inexistent same is absolutely simulated or fictitious • Lack of consideration – prevents existence of a valid contract Failure to pay consideration – contract is still valid because act of payment does not determine the validity of the contract Where cause is: unlawful, contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy, contract is VOID AB INITIO PRESUMPTION OF EXISTENCE LAWFULNESS OF CAUSE • Example: when the consideration in a certain contract is commission of a crime CONTRACTS WITHOUT A CAUSE contract is inexistent absence of essential element (cause) in pari delicto not applicable BOTH CONTRACTS PRODUCE NO EFFECT WHATSOEVER void ab initio in pari delicto applicable AND Under Article 1354, it is presumed that consideration exists and is lawful unless debtor proves on the contrary. Under Sec 3, Rule 131 of the ROC, the ff. are disputable presumptions: UNLAWFUL CAUSE cause exists unlawful If the parties state a false cause in the contract to conceal their real agreement, the contract is relatively simulated and the parties are still bound by their real agreement. if the real price is not stated in the contract, then the contract of sale is still valid but subject to reformation. If the price is simulated, the sale is void, but the act may be shown to have been in reality a donation, or some other act or contract. When the Deed of Sale states that the purchase price has been paid but in fact has never been paid, sale is null and void ab initio and produces no effect whatsoever. but 1. private transactions have been fair and regular 2. the ordinary course of business has been followed 3. there was sufficient consideration for a contract • Effect of legal presumption upon burden of proof – create the necessity of presenting evidence to meet the legal presumption or the prima facie case created thereby. • Presumption stands in the place of evidence unless rebutted. • Burden of overthrowing the presumption – rests on the party to profit from a declaration of nullity of a contract. is TRUE CAUSE Article 1353 • “the statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void, if it should not be proved that they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful.” Samanilla v Cajucom • The presumption of a valid consideration cannot be discarded on a simple claim of absence of consideration, especially when contract states that consideration was given. Page | 151 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CHAPTER 3 Form of Contracts Effect if Lesion or Inadequacy of Cause • Inadequacy of the consideration does not render a contract void, even if gross inadequacy of the price. Reason: Bad Transaction cannot serve as a basis for voiding a contract. Valles vs. Villa • • There must be in addition, a violation of the law, the commission of what the law knows as an actionable wrong, before the courts are authorized to lay hold of the situation and remedy it. Gross inadequacy of the price does not affect the validity of the contract of sale, unless it signifies defect in the consent or that parties actually intended a donation or some other contract. ARTICLE 1355. Except in cases specified by law, lesion or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract, unless there has been fraud, mistake or undue influence Ordinary Sale: • transaction may be invalidated on the ground of inadequacy of price (inadequacy shocks one’s conscience as to justify the courts to interfere) Law gives owner right to redeem: • inadequacy of price should not be material because judgment debtor may re-acquire the property or else sell his right to redeem, thus recover any loss he claims to have suffered by reason of price obtained at the execution sale. Article 1356. Contracts shall be obligatory, in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the essential requisites for their validity are present. However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. In such cases, the right of the parties stated in the following article cannot be exercised. (1278a) Form of Contracts General Rule: No Form Required • The Philippine Contract Law is adhering to the “spiritual system” by upholding the spirit over the form. • No form is required in order to make the contract binding and effective between the parties thereto as stated in the first sentence of Art. 1356: o Contracts shall be obligatory in whatever form they may have been entered into provided all the essential elements for their validity are present.” • Essential elements referred in the above provision are those elements which are required for the perfection of the contract: o Consent o Object certain, which is the subject matter of the contract; o Cause of the obligation which is established • Real Contracts require a fourth element which is: o The delivery of the subject matter of the contract • As long as all the foregoing elements are present, the contract is considered obligatory in whatever form it may have been entered into. In effect, what the first sentence of Art. 1365 is saying is that once a contract is perfected, it is, as a rule, obligatory. It may be made either orally or in writing and, if entered into in writing, it may either be in a private or public instrument. • • Page | 152 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • In general, a certain form may be prescribed by law for any of the following purposes: o Validity ▪ When the form required is for validity, its non-observance renders the contract void and of no effect. o Enforceability ▪ When the form required is for enforceability, non-compliance therewith will not permit, upon the objection of a party, the contract, although otherwise valid, to be proved or enforced by action o Greater efficacy of the contract ▪ Formalities intended for greater efficacy or convenience or to bind third persons, if not done, would not adversely affect the validity or enforceability of the contract between the contracting parties themselves Exceptions: When form is indispensable • Second sentence of Art. 1356: o However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. • • There are two groups of contracts where the requirement of form is absolute and indispensable: o Those contracts which require a certain form for the purpose of their validity o Those contracts which require a certain form for the purpose of proving their existence to be enforceable between the parties o As previously discussed: ▪ When the form required is for validity, its non-observance renders the contract void and of no effect ▪ When the form required is for enforceability, non-compliance therewith will not permit, upon the objection of a party, the contract, although otherwise valid, to be proved or enforced by action There is a third group of contracts which require a certain form, not for the purpose of making the contract valid and enforceable between the parties, but simply for greater efficacy and convenience or for the purpose of making the contract effective as against third persons. o In this group of contracts, the requirement of form is not absolute and indispensable since non-compliance with the formal requirement shall not adversely affect the validity or enforceability of the contract between the contracting parties themselves Form for Validity • In General o In this group of contracts, the law expressly declares the contract to be void or invalid if the formality required by law is not complied with. o While the contract may have been perfected because all the essential requisite are present but if the same is not executed in the form provided by the law creating it, it is void even as between the parties. • Contracts which require a certain form for the purpose of their validity: 1. Donation of personal property exceeding Php5,000 in value 2. Donation of real property 3. Donation propter nuptias 4. Contract of partnership when real property is contributed to the capital 5. Sale of a parcel of land or any any interest therein by an agent 6. Contract if antichresis 7. Sale of transfer of large cattle 8. Chattel mortgage contract 9. Stipulation limiting the common carrier’s liability in carriage of goods • (1) Donation of Personal Property o The formalities of donation involving personal (or movable) property are governed by Art. 748, NCC: ▪ Article 748. The donation of a movable may be made orally or in writing. An oral donation requires the simultaneous delivery of the thing or of the document representing the right donated. If the value of the personal property donated exceeds five thousand pesos, the donation and the acceptance shall be made in writing. Page | 153 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 ▪ Otherwise, the donation Depending therefore on the value of the personal property to be donated, the donation may be made either orally or in writing. o o o WHAT IF THE DONATION IS MADE ORALLY? ▪ If the value of the personal property does not exceed 5K pesos, the donation may be made orally subject, however, to the requirement that there must be simultaneous delivery of the thing or of the document representing the right donated. ▪ If there is no simultaneous delivery, the donation is void. WHAT IF THE DONATION IS IN WRITING? ▪ There is nothing in the law which prevents the donation from being reduced in writing. ▪ If the donation is in writing, note that there is no requirement of simultaneous delivery and the law does not require that the acceptance must also be in writing. ▪ As such, if the value of the personal property to be donated does not exceed 5K pesos and the donation is made in writing, the acceptance may be made either orally or in writing, expressly, or tacitly, and without need of simultaneous delivery. ▪ If the value of the personal property to be donated exceeds 5k pesos, the law mandates that both the donation and the acceptance MUST BE IN WRITING, otherwise, the donation is void. ▪ Donation and acceptance may be embodied either in a private instrument or public instrument. ▪ Furthermore, the law does not require that both donation and acceptance be embodied in a single instrument. Hence, acceptance may be made in a separate instrument and such fact is not required to be noted in both the instruments of donation and acceptance. DONATION OF A SUM OF MONEY ▪ A donation of a sum of money is governed by this law. • Example: • Where the alleged subject of donation was the purchase money in a contract of sale in the amount of 3.2M pesos, the SC held that the donation must comply with the mandatory requirements of Art. 748. • The donation of money equivalent to 3.2M pesos as well as its acceptance should be made in writing, otherwise, it is invalid for non-compliance with the formal requisites prescribed by law. (2) Donation of Real Property o Governed by Art. 749: ▪ Article 749. In order that the donation of an immovable may be valid, it must be made in a public document, specifying therein the property donated and the value of the charges which the donee must satisfy. The acceptance may be made in the same deed of donation or in a separate public document, but it shall not take effect unless it is done during the lifetime of the donor. If the acceptance is made in a separate instrument, the donor shall be notified thereof in an authentic form, and this step shall be noted in both instruments. (633) ▪ [REQUISITES] If what is to be donated is real property, the law mandates that: 1. Both the donation and the acceptance must be embodied in a public instrument, although not necessarily embodied in a single document 2. The real property donated and the value of the charges which the donee is required to satisfy must be specified in the deed of donation 3. If the acceptance is embodied in a separate public document, the donor shall be notified thereof in an authentic form and such step shall be noted in both instruments of donation and acceptance. Page | 154 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • ▪ ▪ All the foregoing requisites must be complied with, otherwise the donation is void [REQUISITE NO. 1] DONATION AND ACCEPTANCE MUST BE IN A PUBLIC INSTRUMENT • Donation of an immovable property must be in a public document for its validity REGARDLESS OF THE VALUE OF THE PROPERTY • Donation of a real property from one person to another will take no effect, unless embodied in a public document • Since a donation is perfected only from the moment the donor knows of the acceptance by the donee, acceptance of the donation by the donee is, therefore, indispensable; absence of acceptance of the donation will make the donation null and void. • When applied to a donation of an immovable property, the law further requires that the acceptance must be made in the same deed of donation or in a separate public document. • If the acceptance is not embodied in a public document, the donation shall also be void. [REQUISITE NO. 3] REQUIREMENT OF NOTIFICATION AND NOTATION • Title to immovable property does not pass from the donor to the donee by virtue of a deed of donation until and unless it has been accepted in a pubic instrument and the donor duly notified theereof. • The acceptance may be made in the very same instrument of donation. If the acceptance does not appear in the same document, it must be made in another • Solemn words are not necessary; it is sufficient if it shows the intention to accept. • But in this case, it is necessaary that formal notice thereof be given to the • • donor, and the fact that due notice has been given must be noted in both instruments (that containing the offer to donate and that showing the acceptance) If the deed of donation fails to show the acceptance, or where the the formal notice of acceptance, made in a separate instrument, is either not given to the donor or else not noted in the deed of donation and in the separate acceptance, the donation is null and void. According to the SC, a strict and literal adherence to the requirement of "notation" in Art. 749 should be avoided if such will result not in justice to the parties but conversely a distortion of their intentions. o Example: ▪ Pajarillo vs IAC, If the donor was not unaware of the acceptance for she in fact confirmed it later and requested that the donated land by not registered during her lifetime, the SC held that it cannot in conscience declare that the donation is ineffective simply because there was no notation for that would be placing too much stress on mere form over substance ▪ Republic vs Silim, Where the acceptance was not noted in the Deed of Donation, the SC held that the actual knowledge by the donor of the construction and existence of the school building pursuant to the condition of the donation already fulfills the legal requirement that the acceptance of the donation by the donee be communicated to the donor. ▪ In Pajarillo and Silim, the SC explained that the purpose of the formal requirement for acceptance of a donation is to senure that such Page | 155 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • acceptance is duly communicated to the donor In Legasto vs Verzosa and Santos vs Robledo, the SC strictly applied the requirement of notation. In Legasto, there was no evidence whatsoever that the claimed donations had been accepted, as stressed by Justice Villa-Real. The same observation was also made in Santos, where the accepance of the donation did not appear in the deed of donation or in any other instrument. (3) DONATION PROPTER NUPTIAS o Donations by reason of marriage are those which are made before its celebration, in consideration of the same, and in favor of one or both of the future spouses. o REQUISITES: ▪ Donation must be made before the celebration of the marriage ▪ It must be made in consideration of the celebration of marriage ▪ It must be made in favor of one or both of the future spouses o It is essential that the donee or donees be ither of the future spouses or both of them, although the donor may either be one of the future spouses or a third person. o Now governed by Article 83 of the Family Code: ▪ Art. 83. These donations are governed by the rules on ordinary donations established in Title III of Book III of the Civil Code, insofar as they are not modified by the following articles. o Article 83 of the Family Code intentionally deleted the clause "except as to their form which shall be regulated by the Statute of Frauds" found in Art. 127, NCC. o With the deletion of such clause, donations propter nuptias are no longer to be governed by the Statute of Frauds with respect to their formalities\ o In view of the applicability of the rules on ordinary donations to donation propter nuptias, the latter must now follow the formal requirements outlined in Art. 748 and 749 of the NCC. • (4) Contract of Partnership Where Realty is Contributed To Capital o A contract of partnership is defined by law as one where two or more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property or industry to a common fund, with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves. o In order to constitute a partnership, it must be established that: ▪ 2 or more persons bound themselves to contribute money, property or industry to a common fund ▪ They intend to divide the profit among themselves. o The agreement need not be formally reduced into writing, the statue allows the oral constitution of a partnership, save in two instances: ▪ When immovable property or real rights are contributed and ▪ When in the partnership has a capital of 3k pesos or more o In both cases, a public instrument is required. o Take note however Art. 1768: ▪ o o Article 1768. The partnership has a juridical personality separate and distinct from that of each of the partners, even in case of failure to comply with the requirements of article 1772, first paragraph. Art. 1772, in turn: ▪ Article 1772. Every contract of partnership having a capital of three thousand pesos or more, in money or property, shall appear in a public instrument, which must be recorded in the Office of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Failure to comply with the requirements of the preceding paragraph shall not affect the liability of the partnership and the members thereof to third persons Further, a contract of partnership may be constituted in any form. This implies that since a contract of partnership is consensual, Page | 156 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 o an oral contract of partnership is as good as a written one. requires that the authority of the agent must be in writing. Pursuant to Art. 1874: WHEN IMMOVABLE PROPERTY IS CONTRIBUTED TO THE PARTNERSHIP AS CAPITAL ▪ ▪ ▪ It is required that there must be an inventory of said property, signed by the parties, and attached to the instrument. If this formality is not followed, the contract of partnership is void. This is pursuant to Article 1773 in relation to Art. 1717: o o o • Article 1771. A partnership may be constituted in any form, except where immovable property or real rights are contributed thereto, in which case a public instrument shall be necessary. • Article 1773. A contract of partnership is void, whenever immovable property is contributed thereto, if an inventory of said property is not made, signed by the parties, and attached to the public instrument. • (6) CONTRACTS OF ANTICHRESIS o WHEN THIRD PARTIES ARE INVOLVED IN THE CONTRACT OF PARTNERSHIP In contract of antichresis the creditor acquires the right to receive the fruits of an immovable of his debtor, with the obligation to apply them to the payment of the interest, if owing, and thereafter to the principal of his credit. In order for this contract to be valid, the law requires that the amount of the principal and of the interest shall be specified in writing, pursuant to Art. 2134: • ▪ o ▪ • In Torres vs CA, the SC explained that the requirement of form in Art. 1773 is intended primarily to pritect third persons. Hence, if the controversy does not involve third parties who may be prejudiced, as when the action is between the partners themselves, they cannot deny the existence of a partnership because of violation of Art. 1773. (5) AGENCY TO SELL LAND OR ANY INTEREST THEREIN o Article 1874. When a sale of a piece of land or any interest therein is through an agent, the authority of the latter shall be in writing; otherwise, the sale shall be void. If the authority of the agent is not in writing, the law declares the sale of the land belonging to the principal to be void and not merely unenforceable. The authority of the agent must be in writing, not the sale made by the agent. With respect to the sale of a parcel of land, the law does not require any form for its validity, although under the Statute of Frauds the sale is required to be in writing for the purpose of making the sale enforceable. If the sale of a parcel of land or any interest therein is made through an agent, the law o o o Article 2134. The amount of the principal and of the interest shall be specified in writing; otherwise, the contract of antichresis shall be void Hence, if the amount of the principal and of the interest is not specified in writing, the contract of anitchresis is void but without affecting the validity of the principal contract of loan. Note: the law does not require that such specification be made in the contract of antichresis itself. Since the contract of antichresis is a mere security to the contract of loan, the former should be interpreted in relation to the latter and, as such, if the amount of the principal and of the interest is already specified in the Page | 157 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 o • o o (7) SALE OF TRANSFER OF LARGE CATTLE o o o o o o • principal contract of loan, the requirement under Art. 2134 is already satisfied. This is in consonance with the rule of contract interpretation known as the "complementary-contracts-construedtogether" doctrine where an accessory contract, such as the contract of antichresis, is required to be read in its entirety and together with the principal agreement The only instance where a certain form is required for validity of the sale is when it involves "large cattle" Formalities of the sale or transfer or large cattle are governed by Act. No. 1147 or the "Cattle Registration Law" Such law specifically provides that no sale or transfer of large cattle shall be considere valid unless the sale or transfer is registered in the office of the municipal treasurer and a certificate of transfer is secured. If the record of such sale or transfer is not registered and the certificate obtained, the sale or transfer is not valid and the ownership of the cattle does not pass. It is implicity required in this law that the sale or transfer of the large cattle must be made in a public instrument since only a public instrument may be accepted for registration. Large cattle includes carabaos, horses, mules, assess and all memebers of the bovine family. (8) CHATTEL MORTGAGE o Art. 2140 of the NCC: ▪ o Article 2140. By a chattel mortgage, personal property is recorded in the Chattel Mortgage Register as a security for the performance of an obligation. If the movable, instead of being recorded, is delivered to the creditor or a third person, the contract is a pledge and not a chattel mortgage While under Sec. 4 of Act No. 1508, the requiremetn of recording is only for the purpose of making the contract bind and effective against third persons o o Art 2140 of the NCC now makes the recording of the contract of chattel mortgage before the chattel mortgage registry as an indispensable requirement for the existence of the contract itslef. The delivery of a personal property to the creditor as security shall constitute a contract of pledge and not a chattel mortgage. In other words, the requirement of recording of the chattel mortgage contract now constitutes as inidspensable requirement for the existence and validity of the said contract. An unrecorded chattel mortgage is not valid even as between the contracting parties Filipinas Marble Corp vs IAC, the SC held that an unregistered chattel mortgage is nevertheless valid beyween the parties thereto. They invoked Art. 2125 of the NCC: • Article 2125. In addition to the requisites stated in article 2085, it is indispensable, in order that a mortgage may be validly constituted, that the document in which it appears be recorded in the Registry of Property. If the instrument is not recorded, the mortgage is nevertheless binding between the parties. The persons in whose favor the law establishes a mortgage have no other right than to demand the execution and the recording of the document in which the mortgage is formalized ▪ However, Art. 2125 of the NCC is inapplicable to a chattel mortgage contract since the said article is found under Chapter 3, Title XVI of Book IV of the NCC, which chapter refers to the contract of a real estate mortgage (REM). ▪ Pursuant to Art. 2141, the provisions of the NCC on REM find no application in chattel mortgage contract, even in a suppletory manner. ▪ What applies instead to a chattel mortgage contract are the provision of the NCC on pledge, insofar as they are not in conflict with the chattel mortgage law. ▪ In addition, the very definition of the contract of chattel mortgage in Art. 2140 requires that there by recording of the Page | 158 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 ▪ • personal property in the Chattel Mortgage registry, otherwise, there is not chattel mortgage contract. Registration is essential to the validity of the chattel mortgage contract (9) Stipulation Limiting Common Carrier's Liability in Carriage Goods o In order for a stupulation between the common carrier and the shipper or owner limiting the liability of the former for the loss, destruction or deterioration of the goods to a degree less than extraordinary diligence to be valid, the same must be in writing and signed by the shipper or the owner FORM FOR ENFORCEABILITY: STATUTE OF FRAUDS: • o Origin of Statute of Frauds o Originated from an English statutory law entitled "An Act for Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries" Statute 29 Charles II chapter 3, enacted in England in 1677. o HISTORY: At early common law, parties to a contract were not allowed to testify and this prohiibtion has led to the practice of hiring third party witness. As early as s the 17th Century, the English recognized the dangers presented by this practice. o PURPOSE: The English Parliament enacted the said statute, the purpose of which is to prevent fraud and perjury in the enforcement of obligations depending for their evidence on the unassisted memory of witnesses by requiring certain enumerated contracts and transactions to be evidenced by a writing signed by the party to be charged. STATUTE OF FRAUDS IN THE PHILIPPINES o o o Originally taken from the Code of Civil Procedure of the State of California. The statute was introduced in the PH by Section 335 of Act 190, the Code of Civil Procedure, and was reproduced as Sec. 21 of Rule 123 of the RoC Realizing that the Statute of Frauds is more substantive than procedural in character, the o CC decided to incorporate the same in the NCC of the Philippines. It can be found under Art. 1402, par. 2: ▪ Article 1403. The following contracts are unenforceable, unless they are ratified: Xxx (2) Those that do not comply with the Statute of Frauds as set forth in this number. In the following cases an agreement hereafter made shall be unenforceable by action, unless the same, or some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent; evidence, therefore, of the agreement cannot be received without the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents: (a) An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; (b) A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another; (c) An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; (d) An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum; (e) An agreement for the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein; (f) A representation as to the credit of a third person. Page | 159 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 o o o Thus, the statute of Frauds is descriptive of statues which require certain classes of contracts to be in writing to be enforceable. The statute does not deprive the parties of the right to contract with respect to the matters therein involved, but merely regulate the formalities of the contract necessary to render it enforceable. They are included in the provisions of the NCC regarding unenforceable contracts, more particularly, Art. 1403 par. 2. PURPOSE OF STATUTE OF FRAUDS • To prevent fraud and perjury in the enforcement of obligations depending for their evidence on the unassisted memory of witnesses by requiring a number of contracts to be evidenced signed by the party to be charged. • NOT designed to further or perpetuate fraud • A contract or bargain within the statute by making and executing note or memorandum, sufficient to state the requirements of the statute. HOW STATUTE OF FRAUDS OPERATES • The statute states that "evidence of the agreement CANNOT be received WITHOUT the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents." • The method by which the contracts enumerated therein may be proved but NOT INVALID because there not reduced to writing. General Rule: By law, contracts are obligatory in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all essential requisites for validity are present. Exception: However, when law requires it to be in some form for it to be valid or enforceable, that requirement is absolute and INDISPENSABLE. Effect of Non-Compliance: o No action can be enforced unless the requirement is complied with. o Used as a DEFENSE when a party to an alleged contract falling within the operation of the Statute attempts to enforce the agreement. • o o Party against whom enforcement is sought MAY OBJECT to presentation of the oral evidence • For evidentiary purposes only If parties permit a contract to be proved WITHOUT OBJECTION, then it is just as binding as if the Statute has been complied with. Example: Sale of parcel of land requires to be in writing to be enforceable under the Statute of Frauds. In a sale where A made a verbal offer to sell it to B, who agreed to buy it for Php 1M and was ready to pay it the following day, but then A changed his mind and did not want to proceed with the sale, then: • Should B go to court, either for specific performance or for recovery damages, he MUST PROVE EXISTENCE OF CONTRACT of sale. • However, since A MAY OBJECT to the presentation of the evidence to prove the existence of the contract under the Statute of Frauds, B is prevented from establishing the existence of said contract. • This results to B not being able to enforce the contract against A. Therefore, contract is UNENFORCEABLE, not void, since A may choose to honor the contract's existence notwithstanding the existence of written proof. SUFFICIENCY OF WRITING o Does not require that contract be in writing o Par. 2, Article 1403: "…some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent…" makes the verbal agreement enforceable, and takes it OUT OF OPERATION OF THE STATUTE. o Requirement of Statute is satisfied when: A) Written contract exists or B) In the absence thereof, some written note or memorandum is signed by the party charged against. Page | 160 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 (a) What Constitutes "Note or Memorandum" o No particular form or language or instrument o Any document or writing, formal or informal, which satisfies all the requirements of a statute as to contents and signature o Can also be not just a single document; two or more writings properly connected may be considered together o Not necessary to establish authenticity of the note or memorandum for the purpose of showing prima facie; only when the trial is held. (b) Note or Memorandum Must Be Complete o Must be complete; cannot rest partly in writing and partly in parol o Must contain: (a) name of the parties, (b) terms and conditions of the contract, (c) and a description of the property sufficient to render it capable of identification. Torcuator vs Bernabe • The special power of attorney and the summary of agreement presented as written evidence did not suffice as notes or memoranda contemplated by Article 1403 of the Civil Code because said documents do not contain the essential elements of the purported contract. Litonjua vs Fernandez • To be binding on the persons to be charged, such note or memorandum must also be signed by the said party or by his agent duly authorized in wiritng. BASIC PRINCIPLES GOVERNING STATUTE OF FRAUDS (a) Applicable Only to PURELY EXECUTORY CONTRACT (b) Applicable to Actions for Violation of Contract or for Its Performance (c) Defense Is EXCLUSIVE to Parties (d) Defense Can Be Waived (e) Defense is Limited to Specific Transactions Applicable Only CONTRACT • to PURELY EXECUTORY The Statute of Frauds applies only to executory contracts. • It does not apply to contracts which have been completely or partially performed. Reason: • • The Statute has precisely been enacted to prevent fraud. If a contract has been totally or partially performed, the exclusion of parol evidence would promote fraud or bad faith, for it would enable the defendant to keep the benefits already delivered by him from the transaction in litigation, and, at the same time, evade the obligations, responsibilities or liabilities assumed or contracted by him thereby. Example: When the seller in a verbal sale of a parcel of land had already accepted a down payment from the buyer, he may no longer invoke the Statute of Frauds to prevent the buyer from establishing the existence of the oral contract by way of parol evidence. Doctrine of Partial Performance • The buyer may now be allowed to introduce parol evidence to prove the existence of the contract since this situation is already taken out of the operation of the Statute of Frauds. Reason: it is not enough for a party to allege partial performance in order to hold that there has been such performance and to render a decision declaring that the Statute of Frauds as inapplicable. • The rejection of any and all testimonial evidence on partial performance, would nullify the rule that the Statute of Frauds is inapplicable to contracts which have been partly executed, and lead to the very evils that the statute seeks to prevent. Rule: Partial execution is even enough to bar the application of the Statute of Frauds. Reason: • It would be fraud upon the plaintiff if the defendant were permitted to escape performance of his part of the oral agreement after he has permitted the plaintiff to perform in reliance upon the agreement. Page | 161 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • For the prevention of fraud, and arose from necessity of preventing the statute from becoming an agent of fraud for it could not have been the intention of the statute to enable any party to commit a fraud with impunity. Note: • • When the party concerned has pleaded partial performance, such party is entitled to a reasonable chance to establish by parol evidence the truth of this allegation, as well as the contract itself. An action by a withdrawing party to recover his partial payment of the consideration of a contract, which is otherwise unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds, by reason of the failure of the other contracting party to comply with his obligation, is not covered by the Statute of Frauds. • Ayson vs Court of Appeals • The statute of frauds may be invoked only by a party to the oral contract, not by a stranger thereto. Defense Can Be Waived It can be waived either by: 1. Failing to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the contract. 2. Accepting benefits therefrom. • Applicable to Actions for Violation of Contract or for Its Performance • • • • The Statute of Frauds does not apply to actions which are neither for violation of a contract nor for the performance thereof. In order that the defendant may successfully invoke the defense of the Statute of Frauds by objecting to the presentation of parol evidence to prove the existence of the contract, the actin must be either for specific performance of the oral contract or for the recovery of damages arising from a violation thereof. The statute may not also be applied to strike out the corroborative testimonies of witnesses of the acquisition of the property in question during marriage because the action was neither for a violation of contract nor the performance thereof. Defense Is EXCLUSIVE to Parties • The defense of the Statute of Frauds can be relied only by the parties to the contract or their representatives or privies, or those whose rights are directly controlled by the statute. Unenforceable contracts, including those which infringe the statute of frauds, cannot be assailed by third persons. Oral evidence of the contract will be excluded upon timely objection. But if the parties to the action, during the trial, make no objection to the admissibility of the oral evidence to support the contract covered by the statute, and thereby permit such contract to be proved orally, it would be just as binding upon the parties as if it had been reduced to writing. Acceptance of benefits under the contract constitutes ratification of the contract infringing the statute of frauds. Defense is Limited to Specific Transactions The following are not covered by the Statute of Frauds: 1. An agreement creating an easement of rightof-way since it is not a sale of real property or of an interest therein; 2. An agreement for the setting up of boundaries, hence, an oral testimony to prove such agreement is admissible. 3. An oral partition of real property is enforceable since partition is not a conveyance of property but simply a segregation and designation of the part of the property which belongs to the co-owners. 4. A right of first refusal is not among those listed as unenforceable under the statute of frauds. It is not by any means a perfected contract of sale of real property. 5. When one of the parties is trying to enforce the delivery to him of 3,000 square meters of land which he claims the defendant orally Page | 162 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 promised to do in consideration of his services as mediator or intermediary in effecting a compromise of a certain civil case since such contract is in no sense a “sale of real property or of any interest therein;” 6. Not applicable to wills or to renunciation or partition of inheritance. Also, not applicable to innominate contract, as where an interpreter rendered services for an inconsiderable number of times; to employment of an attorney; or to a condition upon which a deed is delivered in escrow. Specific Contracts Covered by Statute of Frauds (a) An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; Contract Not To be Performed Within A Year A. In General • An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof is required to be in writing to be enforceable under the Statute of Frauds. • The mischief to be guarded against by this rule is the leaving of the proof of a contract which is to run beyond a year dependent on the memory and truthfulness of witness, or as is sometimes said, to be vouched by parol evidence. • Simply put, because disputes over such contracts have been made, resolution of these disputes is difficult unless the contract has been put in writing. (f) A representation as to the credit of a third person. B. Test in Determining Whether Contract Is Within One-Year Rule • Courts in US have been governed by "not to be performed," have treated them as negative words, and, accordingly, to bring a particular contract within the statute there must be a negation of the right to perform it within a year, that is, it must appear from a reasonable interpretation of the terms of the contract that it is not to be, or is incapable of being, performed within a year. • In other words, the test to determine whether an oral contract is enforceable under the one-year rule of the Statute of Frauds is whether, under its own terms, performance is possible within a year from the making thereof. • If so, the contract is OUTSIDE of the Statute of Frauds and need not be inwriting to be enforceable. • The fact that performance may take more than one year is immaterial as long as performance is possible in less than a year. • One-year period begins to run from the day contract is made. Note: Art. 1443 also requires an express trust concerning an immovable property or any interest therein to be in writing for purpose of proof. Court said requirement is also in the nature of a statute of frauds. C. Applies Only to Agreement Not To be Performed on Either Side • This applies only to agreements not to be performed on either side within a year from the making thereof. (b) A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another; (c) An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; (d) An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum; (e) An agreement for the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein; Page | 163 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • Agreements to be fully performed on one side within a year are taken out of the operation of the statute. This is to prevent frauds and it should not be made the instrument further them. D. Effect of Partial Performance • Contracts which by their terms are not to be performed within one year may be taken out of the SoF through performance by one party thereto. • In other words, when, in an oral contract which, by its terms, is not to be performed within one year from the execution thereof, one of the contracting parties has complied within the year with the obligations imposed on him by said contract, the other party cannot avoid the fulfillment of those incumbent on him under the same contract by invoking the statute of frauds, because the latter aims to prevent and not to protect fraud. • In order that a partial performance of the contract may take the cause out of the operation of the statute, it must appear clear that the full performance has been made by one party within one year, as otherwise the statute would apply. • In other words, there must be complete performance within the year by one party, however many years may have to elapse before the agreement is performed by the other party. But nothing less than full performance by one party will suffice, and it has been held that, if anything remains to be done after the expiration of the year besides the mere payment of the money, the statute will apply. Special Promise to Answer for Debt, Default or Miscarriage of Another A. In General • Any "special promise" to answer for the debt, default or miscarriage of another is required to be in writing or to be evidenced by some note or memorandum signed by the promisor to be enforceable against the latter. • Thus, guaranty propert and suretyship are covered under the Statute of Frauds B. Test in Determining Whether Promise Is Within the Statute • True test, as to whether a promise is within the statute had been said to lie in the answer to the question whether the promise is an original or a collateral one. • If original or independent, that is, if promisor becomes thereby primarily liable for the payment of the debt, the promise is not within the statute. • If promise is collateral to the agreement of another and the promisor becomes thereby merely a surety, the promise must be in writing. C. Covers Contracts of Guaranty and Suretyship • Art. 2055 CC, provides that guaranty is not presumed, but must be express, and cannot extend to more than what is stipulated therein. • This is the obvious rationale as to why contract of guaranty must be in writing. Otherwise, it is unenforceable unless ratified by made in writing or evidenced by some writing. • What is required in order for the contract of guaranty to be enforceable is the undertaking or the special promise of the guarantor (or the offer or proposition for a guaranty), which must also be signed by him. Agreement in Consideration of Marriage • oral agreements made in consideration of marriage are unenforceable under the Statute of Fraud. Marriage Settlement • Article 77 of the Family Code simply requires them to be in writing without providing for the effect if such formal requirement is not followed. • The failure of Article 77 of the Family Code to provide for the effects of failure to comply with the formality required therein is not fatal. Note: Prior to the amendments introduced by the Family Code, the formalities of a marriage settlement were governed by Article 122 of the New Civil Code. Page | 164 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Will this mean that a marriage settlement and its modification are no longer governed by the Statute of Fraud? Example: Ans: Notwithstanding the absence of express provisions in the present article, the marriage settlements and its modifications shall continue to governed by the Statute of Frauds under Article 1403 since marriage settlement is obviously an agreement made in consideration of a marriage. • • • • Contract which infringes the Statute of Frauds is not a void contract but merely unenforceable under the SoF. It is a valid agreement but it cannot be enforced through a court action by either of the parties since its existence cannot be proved without the written agreement. Such oral marriage settlement shall not likewise prejudice the interest of the third persons. Donation Propter Nuptias • They are not governed by the statute of frauds with respect to their formalities. • They are governed by the formalities required in ordinary donations pursuant to the provisions of Article 748 and 749 of the Civil Code in relation to Article 83 of the Family Code. • Prior to the amendments introduced by the Family Code, the formalities required in donation propter nuptias were governed by Art. 127 of the New Civil Code. • An oral donation propter nuptias of a parcel of land is now considered void under the new law, while it is merely unenforceable under the old law. Mutual Promise to Marry • A promise to marry is not covered by the Statute of Frauds. • An oral promise of marriage can be proven by parol evidence. There are instances where such oral promise is necessary in actions for recovery of damages. Gashem Shookat Baksh vs CA • Where the man’s promise to marry is in fact the proximate cause of the acceptance of his love by the woman and his representation to fulfill that promise thereafter becomes the proximate cause of the giving of herself unto him in a sexual congress, the man shall be liable for damages to the woman in the former had, in reality, no intention of marrying the latter and that the promise was only a subtle scheme or deceptive device to entice or inveigle the woman to accept him an to obtain her consent to the sexual act. The award of damages is justified not solely by the breach of promise to marry, but because of the fraud and deceit behind it and the willful injury to the woman’s honor and reputation which followed thereafter. Sale of Goods, Chattels, or things in Action 1. At a price not less than 500 pesos • • A contract for the sale of goods, chattels, or things in action for a price of 500 pesos or more must be in writing. The requirements can be satisfied either by having the contract itself in writing, or by having a subsequent written memorandum of the oral agreement. Illustration: Parties have entered into an oral agreement for the sale of goods for a price of 500 pesos or more and one of the parties thereafter sent a signed confirmation letter to the other party. Can this confirmation letter be considered sufficient to establish the existence of the contract? Ans: The letter can be used by the recipient in the lawsuit against the sender but the latter cannot use the letter against the recipient in a lawsuit because the party against whom the contract enforcement is sought did not signed the written memorandum. Page | 165 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 2. Qualification of the Rule • When the sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, price, names of the purchasers and persons on whose account is made, it is considered as sufficient memorandum, in which case, the sale is enforceable between the purchaser and the person on whose account the sale is made notwithstanding the absence of their signatures in the auctioneer’s sales book. • 3. Exception to Rule • • If the buyer accepts and receives part of the goods and chattels or pay at the time of the purchase money, the transaction is taken out of the Statute of Frauds under the doctrine of partial performance. • • Representations as to credit of third persons • Leasing for more than a year and sale of real property a) Lease of Realty for longer period than one year • • The Statute of Frauds requires that the contract of lease over real property be in writing or be in some note or memorandum signed by the party charged, if the agreement of the leasing is for a longer period than one year. The requirement of the Statute of Frauds is also necessary in case of agreement to renew the lease. Fernandez vs CA • Such alleged verbal assurance of renewal of a lease is inadmissible to qualify the terms of the written lease agreement under the parole evidence rule and unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds. • Have no prescribed form for their validity; they follow the general rule on contracts that they may be entered into in whatever form, provided that all the requisites are present. The representation must have been made by a stranger to the contract in which credit was extended, or, as otherwise stated, the representation must relate to a third person’s credit. Representation as to the credit of the person making the representation are not within the Statute. Express Trust Over Immovable or Any Interest Therein Express Trust • • • b) Sales of Realty • The sale is valid even if it does not contain a technical description of the subject property. The failure of the parties to specify with absolute clarity the object of a contract by including its technical description is of no moment. What us important is that there is an object that is determinate or at least determinable, as subject of the contract of sale. A sale of a real property or any interest therein, to be enforceable, is required to be in writing and signed by the party against whom the contract is being enforced. A formal document is not necessary for the sale transaction to acquire binding effect. • Created by intention of the trustor or of the parties. Stated otherwise, created by the direct and positive acts of the parties, by some writing or deed, or will, or by words either expressly or impliedly evincing an intention to create a trust, although no particular words are required for its creation, it being sufficient that a trust is clearly intended. An express trust concerning an immovable or any interest therein cannot be proved by parol evidence. It must be proven by some writing or deed. Merely for purposes of proof, not for the validity of the trust agreement. Page | 166 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Ringor vs Ringor • Allowed oral testimony to prove the existence of a trust, which had been partially performed. Reason: • The oral character of a trust may be overcome or removed where there has been partial performance of the terms of the trust as to raise an equity in the promise. • When a verbal contract has been completed, executed or partially consummated, its enforceability will not be barred by the Statute of Frauds, which applies only to an executory agreement. Other Contracts Indispensable Where From is Requires that instruments, such as promissory notes and bills of exchange, must be in writing in order to be negotiable. Purpose: for the purpose of making the instrument negotiable and does not affect the validity of the obligation created thereunder. Agreement to Pay Monetary Interest Allowed only if: a. There was an express stipulation for the payment of interest. b. The agreement for the payment of interest as reduced in writing. • • Article 1358. The following must appear in a public document: (1) Acts and contracts which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable property; sales of real property or of an interest therein are governed by articles 1403, No. 2, and 1405; Also Negotiable Instruments • enumerated in the following article, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. (1279a) Collection of interest without any stipulation therefor in writing is prohibited by law. While the creditor may not legally compel the debtor to pay the monetary interest pursuant to an oral agreement for its payment, should the debtor decide to voluntarily pay the same, the creditor is nevertheless authorized to retain the payment. Article 1357. If the law requires a document or other special form, as in the acts and contracts (2) The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains; (3) The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person; (4) The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document. All other contracts where the amount involved exceeds five hundred pesos must appear in writing, even a private one. But sales of goods, chattels or things in action are governed by articles, 1403, No. 2 and 1405. (1280a) Agreement to Pay Monetary Interest: Article 1956. No interest shall be due unless it has been expressly stipulated in writing. (1755a) Payment of Monetary Interest is allowed only if: (requires concurrence of the 2) 1. there was an express stipulation for the payment of interest. Page | 167 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 (Collection of interest without any stipulation is prohibited by law) things in action are governed by articles, 1403, No. 2 and 1405. (1280a) 2. The agreement for the payment of interest was reduced in writing. Form for Greater Efficacy or Convenience: (Monetary Interest is not demandable if the agreement if it is not reduced in writing, and the obligation is treated law as Natural Obligation). Article 1960. If the borrower pays interest when there has been no stipulation therefor, the provisions of this Code concerning solutio indebiti, or natural obligations, shall be applied, as the case may be. (n) The creditor cannot compel the debtor to pay the monetary interest based on oral agreement only, but if the debtor decides to pay the same, the creditor is authorized to retain the payment. Article 1357. If the law requires a document or other special form, as in the acts and contracts enumerated in the following article, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. (1279a) Article 1358. The following must appear in a public document: (1) Acts and contracts which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable property; sales of real property or of an interest therein are governed by articles 1403, No. 2, and 1405; (2) The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains; (3) The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person; (4) The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document. All other contracts where the amount involved exceeds five hundred pesos must appear in writing, even a private one. But sales of goods, chattels or Certain contracts are required to be in a public document not for the validity or enforceability of the contract but only for its greater efficacy or convenience or to bind third persons. Non-compliance does not adversely affect the validity of contract or the contractual rights and obligations of the parties. Dailon vs CA The provision of Article 1358 on the necessity of a public document is only for convenience, not for the validity or enforceability. It is not a requirement for the validity of a contract for sale of a parcel of land that this be embodied in a public instrument. Non-appearance of the parties before the Notary public who notarized the deed does not necessarily nullify or render the parties’ transaction void ab initio. If the sale of parcel of land is in a private instrument, such sale is valid and enforceable between the contracting parties. Effect of Non- recording of the instrument: Even if the Contract of Sale is valid and enforceable between the parties, if the same is not registered, it is not binding upon third persons. The act of registration shall be the operative act to convey or affect the land insofar as third persons are concerned. (Sec 51, P.D. 1529) Thus, the purpose of Art. 1358 in requiring a public document for the contracts named therein is to make said contracts effective upon registration of the instrument in the appropriate registry of property. Contracts Required to Be in Public Document for Convenience: Under Art. 1358, the ff. contracts are required to appear in a public document but only for the purpose of greater efficacy or convenience or to bind third persons: 1. Acts and omissions which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable Page | 168 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 property; sales of real property or of an interest therein are governed by articles 1403, No. 2 and 5 2. The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains. 3. The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person. 4. The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document. Contract of Real Estate Mortgage governed by Art. 2085-2092 and 2124-2131 of the Civil Code. do not require any formality to make the contract valid and enforceable between the parties. However, for the purpose of making the contract effective upon third persons, the law requires that the Mortgage be recorded in the Registry of Property. Article 2125. In addition to the requisites stated in article 2085, it is indispensable, in order that a mortgage may be validly constituted, that the document in which it appears be recorded in the Registry of Property. If the instrument is not recorded, the mortgage is nevertheless binding between the parties. The persons in whose favor the law establishes a mortgage have no other right than to demand the execution and the recording of the document in which the mortgage is formalized. (1875a) since only a public document may be recorded, it is implicit in the requirement that contract of real estate mortgage must be contained in a public document for it to be registrable in the Registry of Property. Contract of Sale over a Parcel of Land: The Statute of Frauds require this contract to be in writing to be enforceable. additional requirement that the contract must appear in a public document but only for the convenience of the parties thereto. though not consigned in a public instrument or formal writing is valid and binding among the parties (does not affect the validity of such conveyance) Contracts Required to be in Writing under Article 1358 all other contracts where the amount involved exceeds five hundred pesos must appear in writing, even a private one. But sales of goods, chattels, or things in action are governed by Articles 1403, No. 2 and 1405. merely for convenience and not for the purpose of validity and enforceability. (Shaffer vs. Palma) Remedy granted under Article 1357 For contracts which are required to be in a certain form, such as those enumerated in Art 1358 which are required to be in a public document, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, and this right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. In order for this remedy to be exercised, the following requisites must concur: 1. the contracts must have already been perfected 2. the contract must have been valid as to form 3. the contract must have been enforceable under the Statute of Frauds Thus, when a contract is enforceable under the Statute of Frauds, and a public document is necessary for its registration in the Registry of Deeds, the parties may avail themselves of the right under Art 1357. Illustration: Sale of Parcel of Land o if evidenced by a private instrument signed by both parties, they may compel each other to execute the formal public document of sale as required in Art. 1358. Such sale is outside the purview of the Statute of Frauds. • Sale is valid and effective Verbal Sale of a Parcel of Land purely executory neither of the parties can avail of the remedy under Art 1357 since the contract is unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds Page | 169 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CHAPTER 4 Reformation of Instruments (n) Article 1359. When, there having been a meeting of the minds of the parties to a contract, their true intention is not expressed in the instrument purporting to embody the agreement, by reason of mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct or accident, one of the parties may ask for the reformation of the instrument to the end that such true intention may be expressed. If mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident has prevented a meeting of the minds of the parties, the proper remedy is not reformation of the instrument but annulment of the contract. Article 1360. The principles of the general law on the reformation of instruments are hereby adopted insofar as they are not in conflict with the provisions of this Code. Reformation • A remedy in equity, whereby a written instrument is made or construed so as to express or conform to the real intention of the parties, where some error or mistake has been committed. Rationale: it would be unjust and inequitable to allow the enforcement of a written instrument which does not reflect or disclose the real meeting of the minds of the parties. • • In granting information, the remedy in equity is not making a new contract for the parties, but establishing and perpetuating the real contract between the parties which, under the technical rules of law, could not be enforced but for such reformation. Equity renders the reformation of an instrument in order that the true intention of the contracting parties may be expressed. National Irrigation Administration vs Gamit Reformation of Contracts vs Interpretation of Contracts Reformation of Contracts A remedy in equity, whereby a written instrument is made or construed so as to express or conform to the real intention of the parties In granting information, the remedy in equity is not making a new contract for the parties, but establishing and perpetuating the real contract between the parties which, under the technical rules of law, could not be enforced but for such reformation. Rationale: it would be unjust and inequitable to allow the enforcement of a written instrument which does not reflect or disclose the real meeting of the minds of the parties. Interpretation of Contracts The act of making intelligible what was before not understood, ambiguous, or not obvious. It is a method by which the meaning of language is ascertained. It is the determination of the meaning attached to the words written or spoken which make the contract. Requisites of Reformation 1. There must have been a meeting of the minds of the parties to the contract; 2. The instrument does not express the true intention of the parties; and 3. The failure of the instrument to express the true intention of the parties is due to mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct or accident. • The presumption is that an instrument sets out the true agreement of the parties thereto and that it was executed for valuable consideration. Page | 170 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • In actions for reformation of contract, the onus probandi is upon the party who insists that the contract should be reformed. Effect of Mutual Mistake of Parties • • When mutual mistake of the parties causes the failure of the instrument their real agreement, said instrument may be reformed. When the mutual error of the parties relates to the legal effect of their agreement which frustrates the real purpose of the contract, the consent is vitiated and the remedy is not reformation of the instrument but the annulment of the contract. In order for reformation of the instrument by reason of mutual mistake to be applicable, it is necessary that – 1. The mistake should be of fact; 2. The same should be proved by clear and convincing evidence; and 3. The mistake should be common to both parties to the instrument. Article 1361. When a mutual mistake of the parties causes the failure of the instrument to disclose their real agreement, said instrument may be reformed. Article 1362. If one party was mistaken and the other acted fraudulently or inequitably in such a way that the instrument does not show their true intention, the former may ask for the reformation of the instrument. Article 1363. When one party was mistaken and the other knew or believed that the instrument did not state their real agreement, but concealed that fact from the former, the instrument may be reformed. Article 1364. When through the ignorance, lack of skill, negligence or bad faith on the part of the person drafting the instrument or of the clerk or typist, the instrument does not express the true intention of the parties, the courts may order that the instrument be reformed. Article 1365. If two parties agree upon the mortgage or pledge of real or personal property, but the instrument states that the property is sold absolutely or with a right of repurchase, reformation of the instrument is proper. Instances where instrument may be reformed The following instances the reformation of the instrument is authorized: 1. When a mutual mistake of the parties causes the failure of the instrument to disclose their real agreement. 2. If one party was mistaken and the other acted fraudulently or inequitably in such a way that the instrument does not show their true intention. 3. When one party was mistaken and the other knew or believed that the instrument did not state their real agreement, but concealed that fact from the former. 4. When through the ignorance, lack of skill, negligence or bad faith on the part of the person drafting the instrument or of the clerk or typist, the instrument does not express the true intention of the parties. 5. If two parties agree upon the mortgage or pledge of real or personal property, but the instrument states that the property is sold absolutely or with a right of repurchase. Article 1366. There shall be no reformation in the following cases: (1) Simple donations inter vivos wherein no condition is imposed; (2) Wills; (3) When the real agreement is void. Article 1367. When one of the parties has brought an action to enforce the instrument, he cannot subsequently ask for its reformation. Instances reformed where instrument may not be Page | 171 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. If mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct, or accident has prevented a meeting of the minds of the parties. Here, the remedy is annulment of the contract and not reformation. 2. In simple donation inter vivos wherein no condition is imposed 3. In wills 4. When the real agreement us void. 5. When one of the parties has brought an action to enforce the instrument, he cannot subsequently ask for its reformation. 6. When the contract is unenforceable because of failure to comply with the Statute of Frauds. Article 1368. Reformation may be ordered at the instance of either party or his successors in interest, if the mistake was mutual; otherwise, upon petition of the injured party, or his heirs and assigns. Article 1369. The procedure for the reformation of instrument shall be governed by rules of court to be promulgated by the Supreme Court. Who may demand reformation? 1. If the mistake was mutual, either party or his successor-in-interest may demand for reformation. 2. If the mistake was not mutual, only the injured party or his heirs and assigns may demand for reformation. Note: • The party who has brought an action to enforce the instrument cannot subsequently ask for its reformation. CHAPTER 5 Interpretation of Contracts Article 1370. If the terms of a contract are clear and leave no doubt upon the intention of the contracting parties, the literal meaning of its stipulations shall control. If the words appear to be contrary to the evident intention of the parties, the latter shall prevail over the former. (1281) Article 1371. In order to judge the intention of the contracting parties, their contemporaneous and subsequent acts shall be principally considered. (1282) Article 1372. However general the terms of a contract may be, they shall not be understood to comprehend things that are distinct and cases that are different from those upon which the parties intended to agree. (1283) Article 1373. If some stipulation of any contract should admit of several meanings, it shall be understood as bearing that import which is most adequate to render it effectual. (1284) Article 1374. The various stipulations of a contract shall be interpreted together, attributing to the doubtful ones that sense which may result from all of them taken jointly. (1285) Article 1375. Words which may have different significations shall be understood in that which is most in keeping with the nature and object of the contract. (1286) Article 1376. The usage or custom of the place shall be borne in mind in the interpretation of the ambiguities of a contract, and shall fill the omission of stipulations which are ordinarily established. (1287) Article 1377. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity. (1288) Article 1378. When it is absolutely impossible to settle doubts by the rules established in the preceding articles, and the doubts refer to incidental circumstances of a gratuitous contract, the least transmission of rights and interests shall prevail. If the contract is onerous, the doubt shall be settled in favor of the greatest reciprocity of interests. Page | 172 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 If the doubts are cast upon the principal object of the contract in such a way that it cannot be known what may have been the intention or will of the parties, the contract shall be null and void. (1289) Article 1379. The principles of interpretation stated in Rule 123 of the Rules of Court shall likewise be observed in the construction of contracts. (n) Rules in Interpretation of Contracts 1. Cardinal Rule: Intention prevails a. Intention of the contracting parties should always prevail because their will has the force of law between them i. The intention of the parties is primordial and once the intention is ascertained, that element is deemed as an integral part of the contract as though it has been originally expressed in unequivocal terms b. How to ascertain: based on the meaning attached to the words written or spoken which make the contract i. If the written instrument does not reflect the real intention of the parties, due to mistake, fraud, inequitable conduct or accident, remedy is reformation c. Process of ascertaining intent: objective manifestation i. Court makes a preliminary inquiry as to whether the contract is ambiguous 1. If ambiguous, interpretation left to the courts (resolve using intrinsic evidence + the rules stated below in number 3 "when there is ambiguity") a. Ambiguous: susceptible of 2 reasonable alternative interpretations 2. If clear and unambiguous (i.e. can only be read one way), court will interpret the contract as a matter of law (just apply it, nothing else to be done) 2. Terms of Contract are clear a. If the terms of a contract are clear and leave no doubt upon the intention of the contracting parties, the literal meaning of its stipulations is controlling (Art. 1370, NCC 1st par.) b. Where the language of a contract is plain and unambiguous, meaning should he determine without reference to extrinsic facts or aids i. Intention of the parties must be gathered from that language alone. c. Courts thus have no authority to alter a contract by construction or to make a new contract for the parties 3. When there is ambiguity a. Ambiguous: susceptible of 2 reasonable alternative interpretations b. Extrinsic evidence i. Parol evidence rule: prohibits any addition or contradiction of the terms of a written instrument by testimony or other evidence purporting to show that, at or before the execution of the parties' written agreement, other or different terms were agreed upon by the parties, varying the purport of the written contract 1. Exception a. Failure of the written agreement to express the true intent and agreement of the parties thereto (very ambiguous or obscure; intention of the parties cannot be understood) ii. Art. 1371, NCC: "In order to judge the intention of the contracting parties, their contemporaneous and subsequent acts shall be principally considered" 1. Analysis by a. Words of the Contract b. Reason behind and circumstances under which the contract was executed iii. But if clear and unambiguous, no need for extrinsic evidence (only intrinsic) c. Contra proferentem (Construe against drafting parties) i. Art. 1377, NCC: The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity 1. Contracts of adhesion: ambiguities are construed against the party who prepared the contract d. Principle of Effectiveness Page | 173 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 i. 2 interpretations of the same contract are possible: 1. One rendering the contract meaningless, invalid and illegal 2. One giving effect to the contract as a whole, valid and legal ii. Art. 1373, NCC: Choose the latter hehehe e. Contract interpreted as a whole i. Provisions should be read in relation to each other and in their entirety so as to render them effective ii. Art. 1374, NCC: various stipulations of a contract shall be interpreted together attributing to the doubtful ones that sense which result from all of them taken jointly iii. Doctrine of complementary-contractsconstrued-together (Art. 1374, NCC) 1. An accessory contract must be read in its entirety and together with the principal agreement 2. Ex. Surety contract as an accessory contract to be interpreted together with the loan agreement as the principal contract f. In keeping with the nature and object of the contract i. Art. 1375, NCC: words which may have different significations shall be understood in that which is most in keeping with the nature and object of the contract ii. Duty of the courts to place a practical and realistic construction upon it, giving due consideration to the context in which it is negotiated and the purpose which it is intended to serve (i.e. reasonable construction) g. Eusdem Generis (Limit Generalities to Things of Same Genre) i. Art. 1372, NCC: However general the terms of a contract may be, they shall not be understood to comprehend things that are distinct and cases that are different from those upon which the parties intended to agree ii. Eusdem Generis rule: where general words follow the enumeration of particular classes of persons or things, the general words will be construed as applicable only to persons or things of the same general nature or class as those enumerated h. Usage or customs i. Art. 1376, NCC: the usage or custom of the place shall be borne in mind in the interpretation of the ambiguities of a contract, and shall fill the omission off stipulations which are ordinarily established i. In case of impossibility to settled doubts by other rules/i.e. those listed above (Art. 1378, NCC) i. If doubts refer to incidental circumstances of a gratuitous contract, the least transmission of rights and interests shall prevail ii. If the contract is onerous, the doubt shall be settled in favor of the greatest reciprocity of interests; and iii. If the doubts are cast upon the principal object of the contract in such a way that it cannot be known what may have been the intention or will of the parties, the contract shall be null and void 4. Rules of Interpretation of Documents under ROC Rules of Interpretation of Documents Under Rules of Court • Article 1379 of the Civil Code provides that "the principles of interpretation stated in Rule 130 of the Rules of Court shall likewise be observed in the construction of contracts" • Section 10 up to 19 of Rule 130 of the Rules of Court provides for the rules of interpreting documents: o Section 10. Interpretation of a writing according to its legal meaning. — The language of a writing is to be interpreted according to the legal meaning it bears in the place of its execution, unless the parties intended otherwise. o Section 11. Instrument construed so as to give effect to all provisions. — In the construction of an instrument, where there are several provisions or particulars, such a construction is, if possible, to be adopted as will give effect to all. Section 12. Interpretation according to intention; general and particular provisions. — In Page | 174 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 the construction of an instrument, the intention of the parties is to be pursued; and when a general and a particular provision are inconsistent, the latter is paramount to the former. So a particular intent will control a general one that is inconsistent with it. o Section 13. Interpretation according to circumstances. — For the proper construction of an instrument, the circumstances under which it was made, including the situation of the subject thereof and of the parties to it, may be shown, so that the judge may be placed in the position of those who language he is to interpret. o Section 14. Peculiar signification of terms. — The terms of a writing are presumed to have been used in their primary and general acceptation, but evidence is admissible to show that they have a local, technical, or otherwise peculiar signification, and were so used and understood in the particular instance, in which case the agreement must be construed accordingly. o Section 15. Written words control printed. — When an instrument consists partly of written words and partly of a printed form, and the two are inconsistent, the former controls the latter. o Section 16. Experts and interpreters to be used in explaining certain writings. — When the characters in which an instrument is written are difficult to be deciphered, or the language is not understood by the court, the evidence of persons skilled in deciphering the characters, or who understand the language, is admissible to declare the characters or the meaning of the language. o Section 17. Of Two constructions, which preferred. — When the terms of an agreement have been intended in a different sense by the different parties to it, that sense is to prevail against either party in which he supposed the other understood it, and when different constructions of a provision are otherwise equally proper, that is to be taken which is the most favorable to the party in whose favor the provision was made. o Section 18. Construction in favor of natural right. — When an instrument is equally susceptible of two interpretations, one in o favor of natural right and the other against it, the former is to be adopted. Section 19. Interpretation according to usage. — An instrument may be construed according to usage, in order to determine its true character. Page | 175 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Introduction to Defective Contracts Defective Contracts • Kinds of Contracts as to Defects Contracts are classified either as: • • Perfectly Valid – where the contract does not suffer from any defect. Defective – where the contract suffers from a certain kind of defect. Classification of defective contracts: • • • • Rescissible Voidable Contracts Unenforceable Contracts Void or Inexistent Contracts Rescissble Contracts • • Contains all the requisites of a valid contract and are considered legally binding, but by reason of injury or by damage (lesion) to either of the contracting parties or to third persons, such as creditors, it is susceptible to rescission at the instance of the party who may be prejudiced thereby. A rescissible contract is valid, binding and effective until it is rescinded. Voidable Contract • • One in which the essential requisites for validity under Article 1318 are present, but may be annulled because of want of capacity or the vitiated consent of one of the parties. Before such annulment, the contract is existent, valid, and binding, hence, considered effective and obligatory between parties. Unenforceable Contract • Is that which cannot be enforced by a proper action in court, unless it is ratified, because either it is entered into without or in excess of authority or it does not comply with the • statute of frauds or where both of the contracting parties do not possess the required legal capacity. Prior to ratification, the contract is valid but it cannot be enforced by a proper action in court. Once ratified, either expressly or impliedly, it is rendered perfectly valid and becomes obligatory between the parties. Void or Inexistent Contract • • • Is one which has no force and effect from the very beginning. It is as if it has never been entered into and cannot be validated either by the passage of time or by ratification. Void contract is more infer that inexistent contract. Clarification of Terms • • • Rescissble and voidable contracts are both obligatory until they are rescinded or annulled, respectively. Unenforceable contracts are not obligatory unless they are ratified. Void or inexistent can never become obligatory since the defect is not subject to ratification. Perfection • • Is synonymous with the birth of the contract or its existence. It takes place upon the concurrence of all the essential elements thereof. There are two ways by which a contract may perfected: 1. Consensual – its perfection is perfected by mere consent. This kind of contract comes into existence upon the concurrence of three essential requisites: consent, object, and cause. 2. Real – its perfection is not perfected by mere consent but by the delivery of the object of the contract. This kind of contract comes into existence upon the concurrence of four Page | 176 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 essential requisites: consent, object, cause and delivery. Inexistent Contract is used to refer to contracts which are made to appear as existing but in reality, they do not exist either because: Note: In the Civil Code, there are only four contract that are classified as real contracts, namely, pledge, deposit commodatum, and nutuum. • 1. It is merely absolutely simulated or fictitious. 2. Its cause or object did not exist at the time of the transactions. 3. The intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained. A contract is obligatory once it is perfected, regardless of the form it may have been entered into. Under Article 1315, from the moment the contract is perfected, “the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law.” Under Article 1356, the general rule is that “contracts shall be obligatory, in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the essential requisites for their validity are present.” Unenforceable are perfected and valid contracts but they cannot be enforced by a proper action in court unless they are ratified. A void contract contains all essential elements (consent, object, cause, or delivery of the object of the contract) but it is invalid from the very beginning because: Example: A contract entered into in the name of another person by one who has been given no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers. • • 1. Its cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. 2. Its object is outside the commerce of men. 3. It contemplates an impossible service. 4. It is expressly prohibited or declared void by law, such as contracts which violate the principle of mutuality of contracts and contracts which require a certain form for their validity and the requirement is not complied with. Void Contracts Inexistent Contracts Contains all the In reality, it does not essential elements exist. of a contract. • • • • • The principle of pari delicto is applicable only to contracts with an illegal cause or subject matter (object) and does not apply to inexistent contracts, such as those absolutely simulated or fictitious. Pari delicto rule presupposes the existence of a cause, it cannot refer to fictious or simulated contracts which are in reality nonexistent. Once the contract is cleansed of its defect by ratification, the same becomes enforceable and is, therefore, obligatory. A contract is obligatory only between the parties, as well as assigns and heirs A contract that is obligatory is binding between the parties, their assigns and heirs. CHAPTER 6 Rescissible Contracts Article 1380. Contracts validly agreed upon may be rescinded in the cases established by law. (1290) Rescissible Contracts Rescission is found in: Page | 177 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. Article 1191 – the general provision on rescission of reciprocal obligations. 2. Article 1381 – rescission of rescissible contracts. 3. Article 1592 – rescission of a contract of sale of an immovable property. 4. Article 1659 – rescission as an alternative remedy, insofar as the rights and obligations of the lessor and the lessee in contracts of lease are concerned. The breach contemplated is the obligor’s failure to comply with an existing obligation. Thus, the power to rescind is given only to the injured party. Rescission under Article 1191 vs Rescission under Article 1381 The Civil Code uses rescission in two different contexts: 1. Rescission on account of breach of contract under Article 1191. 2. Rescission by reason of lesion or economic prejudice under Article 1381. • The rescission under Article 1991 is called “resolution.” Article 1991 Not predicated on injury to economic interests of the party plaintiff but on the breach of faith by the defendant, that violates the reciprocity between the parties. The rescission applies exclusively to the reciprocal obligations. The rescission is a principal action which seeks the resolution or cancellation of the contract. Article 1381 The cause of action is subordinated to the existence of lesion or economic prejudice because it is the rasion d ‘etre as well as the measure of the right to rescind. The rescission applies to all kinds of obligations arising from contracts, whether the same be reciprocal in character or not. The rescission is only a subsidiary remedy, meaning, it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means The court has discretionary power not to grant the rescission if there be just cause for the fixing of a period for the performance of the obligation. to obtain reparation for the same. Even a third person can become an injured party as in the case of contracts I fraud of creditor. The latter acquires the right to rescind the contract which is entered into for the purpose of defrauding him, even if he is not a party to said contract. The court must order the rescission once the ground is proven. Note: • • The four-year prescriptive period provided for in Article 1389 applies only to rescission as a subsidiary remedy and not to rescission as a principal action under Article 1191. As to rescission as a principal action in Articles 1191, 1592, and 1659, the prescriptive period applicable is found in Article 1144, which provides that the action upon a written contract should be brought within ten years from the time the right of action accrues. Rescission Distinguished from Termination of Contracts Rescission of Contracts When a contract is rescinded, it is deemed inexistent, and the parties are returned to their status quo ante. Termination of Contracts When the agreement is terminated, it is deemed valid at inception. Prior to its termination, the Page | 178 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Hence, there is contract binds the mutual restitution of parties, who are benefits received. thus obliged to observe its provisions. To rescind is to The termination or declare a contract cancellation of a void in its inception contract would and to put an end to necessarily entail it as though it never enforcement of its were. It is not terms prior to the merely to terminate declaration of its it and release cancellation in the parties from further same way that obligations to each before a lessee is other but to ejected under a abrogate it from the lease contract, he beginning and has to fulfill his restore the parties obligations to relative positions thereunder that had which they would accrued prior to his have occupied had ejectment. no contract ever However, been made. termination of a contract need not undergo judicial intervention. • Article 1381. The rescissible: • • The parties in a case of termination are not restored to their original situation; neither is the contract treated as if it never existed. Prior to its termination, the parties are obliged to comply with their contractual obligations. Only after the contract has been cancelled will they be released from their obligations. Huibonhoa vs CA • • following contracts are (1) Those which are entered into by guardians whenever the wards whom they represent suffer lesion by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object thereof; (2) Those agreed upon in representation of absentees, if the latter suffer the lesion stated in the preceding number; (3) Those undertaken in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any other manner collect the claims due them; (4) Those which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority; Note: • The parties have, in legal effect, simply entered into another contract for the dissolution of the previous one, and its effects, in relation to the contract so dissolved, should be determined by the agreement of the parties, or by the application of other legal principals, but not by Article 1385. (5) All other contracts specially declared by law to be subject to rescission. (1291a) Article 1382. Payments made in a state of insolvency for obligations to whose fulfillment the debtor could not be compelled at the time they were effected, are also rescissible. (1292) Concept of Rescission Under Article 1381 Where the action for the rescission of a lease contract prayed for the payment of rental arrearages, the aggrieved party actually sought the partial enforcement of a lease contract. The remedy was not actually rescission, but termination or cancellation, of the contract. Rescission Distinguished from Mutual Dissent • The rescission contemplated in Articles 1380 to 1389 is a remedy granted to the contracting parties and even to third persons, to secure the reparation of damages caused to them by a contract, even if this should be valid, by restoration of things to their condition at the moment prior to the celebration of the contract. It implies a Page | 179 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • contract, which even if initially valid, produces a lesion or a pecuniary damage to someone. The action cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damages has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. Nature of Rescissible Contracts Under Article 1381 • • • • Contracts which are rescissible are valid contracts having all the essential requisites of a contract and therefore obligatory under normal conditions, but by reason of injury or damage caused to either of the parties therein or third persons are considered defective and, thus, may be rescinded. The defect of a rescissible contract under Article 1381 may not be cleansed by ratification although the right of action for rescission may be lost by way of extinctive prescription. The defect of a rescissible contract cannot be attacked collaterally. An action for rescission must be set up in an independent civil action and only after full blown trial. Requites for Rescission to Prosper 1. The action for rescission must be originate from any of the causes specified in Articles 1381 and 1382. 2. The party suffering damage and who is asking for rescission has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the damage suffered by him. 3. The person demanding rescission must be able to return what he may be obliged to restore if rescission is granted by the court. • This requisite does not apply to a creditor suing for rescission under Article 1381 (3) because he received nothing from the contract which he seeks to rescind. 4. The things are the object of the contract must not be legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith. 5. The action for rescission must be filed within four years from accrual of the right of action. Specific Contracts Declared Rescissible Kinds of Rescissible Contracts According to the reason for their susceptibility to rescission: 1. Those which are rescissible because of lesion or prejudice. 2. Those which are rescissible on account of fraud or bad faith. 3. Those which, by special provisions of law, are susceptible to rescission. The following contracts are rescissible by reason of lesion or prejudice: 1. Those which are entered into by guardians whenever the wards whom they represent suffer lesion by more than one-fourth of the value of the things which are the object thereof 2. Those agreed upon in representation of absentees, if the latter suffer the lesion stated in the preceding number 3. Partition of inheritance where an heir suffers lesion of at least ¼ of the share to which he is entitled. The following contracts are rescissible on account of fraud or bad faith: 1. Those undertaken in fraud of creditors when the latter cannot in any other manner collect the claims due them 2. Those which refer to things under litigation if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority 3. Payments made in a state of insolvency for obligations to whose fulfillment the debtor could not be compelled at the time they were effected Page | 180 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • Contracts which are specially declared by law to be subject to rescission: Articles 1189, 1191, 1526, 1534, 1539, 1542, 1556, 1560, 1567, 1592, and 1659. Rescissible By reason of Lesion or Prejudice Lesion – injury which one of the parties suffers by virtue of a contract which is disadvantageous to him. unenforceable in accordance with Articles 1317 and 1403 (1). • Note: • Scope and Coverage • • • • For contract to be rescissible, the lesion must exceed 25% of the value of the thing owned by the ward or absentee. The rescissible contracts referred to in paragraph 1 and 2 of Article 1381 presuppose the absence of court approval because if prior court approval is obtained, the contract would be valid, regardless of the presence of lesion. Administration includes all acts for the preservation of the property and the receipt of fruits according to the natural purpose of the thing. The right to administer does not include the power to dispose or encumber said property without court authorization. • • • Under the Rules of Court, any disposition or encumberance by the guardian or administrator of real property of the ward or of the absentee requires prior court approval. What then is the effect of the absence of such approval? • The guardian is prohibited from acquiring by way of purchase, either in person r through the mediation of another, the property of his ward whether such purchase is made at a public or judicial auction. Basis: Article 1491. The following persons cannot acquire by purchase, even at a public or judicial auction, either in person or through the mediation of another: (1) The guardian, the property of the person or persons who may be under his guardianship; Answers: 1. The Court declared void a sale of the ward’s realty by the guardian without authority from the court. 2. The Court ruled that any disposition of the property of the ward (minor) without the proper judicial authority, unless ratified by them upon reaching the age of majority, is The contract of disposition or encumberance of realty entered into by the guardian or administrator is unenforceable and not rescissible, irrespective of whether there is lesion or not. If prior court approval is obtained, the contract would be valid, regardless of the presence of lesion. If such contract is entered into by the guardian without court approval and the ward suffers lesion to the extent provided for in the said article, such contract may be rescinded. If such contract is approved by the court, there is no ground for rescission even if the ward suffers lesion to the extent provided for in Par. 1 of Art. 1381. Guardian cannot Acquire Property of Ward Sale or Encumberance of Real Property of Ward or Absentee • The second answer is the better view. x x x. • • Any sale in violation of the prohibition is void and not merely voidable. The sale is prohibited only while the guardianship exists. Page | 181 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • After the termination of the guardianship, the prohibition no longer applies. The transaction may be ratified by means of and in the form of a new contract, in which case its validity shall be determined only by the circumstances at the time the execution of such new contract. The new contract would then be valid from its execution; however, it does not retroact to the date of the first contract. • • • Contracts in Fraud of Creditor a. Accion Pauliana • Contracts undertaken in fraud of creditors are rescissible under the provisions of the third paragraph of Article 1381, when the latter cannot in any manner collect the claims due them. Accion Pauliana • • • This remedy is available when the subject matter is a conveyance, otherwise valid, undertaken in fraud of creditor. Contracts which are rescissible under the third paragraph of Article 1381 are valid contracts, albeit undertaken in fraud of creditors. If the contract is absolutely simulated, the contract is not merely rescissible but inexistent, albeit undertaken as well in fraud of creditors. Difference between contracts that are rescissible for having been undertaken in fraud of creditors and absolutely simulated contracts which are also undertaken in fraud creditors. • • • An absolutely simulated contract, under Art. 1346 is void. It takes place when the parties do not intend to be bound at all. The characteristic of simulation is the fact that the apparent contract is not really desired or intended to produce legal effects or in any way alter the juridical situation of the parties. • The remedy of accion pauliana is available when the subject matter is a conveyance, otherwise valid, undertaken in fraud of creditors. A void or inexistent contract is one which has no force and effect from the very beginning, as if it had never been entered into; it produces no effect whatsoever either against or in favor of anyone. Rescissble contracts are not void ab initio, and the principle, “quod nullum set nullum producit effectum,” in void inexistent contracts is inapplicable. Until set aside in an appropriate action, rescissible contracts are repsected as being legally valid, binding and in force. Absolute Simulation vs Fraudulent Simulation Absolute Simulation Implies that there is no existing contract, no real act executed. Can be attacked by any creditor, including one subsequent to the contract. The insolvency of the debtor making the simulated transfer is not a prerequisite to the nullity of the contract. The action to declare a contract absolutely simulated does not prescribe (articles 1409 and 1410) Fraudulent Simulation There is a true and existing transfer or contract. Can be assailed only by the creditors before the alienation. The action to rescind, or accion pauliana, requires that the creditor cannot recover in any other manner what is due him. The accion pauliana to rescind a fraudulent alienation prescribes in four years (article 1389) Requisites of Accion Pauliana and Prescriptive Period 1. The plaintiff asking for rescission has a credit prior to the alienation, although demandable later. Page | 182 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 2. The debtor has made a subsequent contract conveying a patrimonial benefit to a third person. 3. The creditor has no other legal remedy to satisfy his claim. 4. The act being impugned is fraudulent. 5. The third person who received the property conveyed, if it is by onerous title, has been an accomplice in the fraud. • • • Rescission requires the existence of creditors at the time of the alleged fraudulent alienation, and this must be proved as one of the bases of the judicial pronouncement setting aside the contract. While it is necessary that the credit of the plaintiff in the accion pauliana must exist prior to the fraudulent alienation, the date of the judgement enforcing it is immaterial. Right of First Refusal Jurisprudential Development • • It is further required that the conveyance must not be absolutely simulated. General Rule: • Paranaque Kings Enterprises, Inc. vs Court of Appeals. • Note: • Right of First Refusal • A contract entered into in violation of a right of first refusal is rescissible. • The status of creditor can be validly accorded to grantees of the right of first refusal for they have substantial interests that will be prejudiced by the conveyance of the property subject matter of their right of first refusal. Equatorial Realty Development, Inc. vs Mayfair Theater, Inc. • The term creditors in Article 1381 (3) is broad enough to include the oblige under an option contract as well as under a right of first refusal, sometimes known as a right of first priority. A contract of sale entered into in violation of a right of first refusal of another person, while valid, is rescissible. Concept of Right of First Refusal Guzman, Bicaling & Bonnevie • In order to have full compliance with the contractual right granting petitioner the first option to purchase, the sale of the properties for the price for which they were finally sold to a third person should have likewise been first offered to the former. There should be identity of terms and conditions to be offered to the buyer holding a right of first refusal if such right is not to be rendered illusory. The basis of the right of first refusal must be the current offer to sell of the seller or offer to purchase of any prospective buyer. • A contractual grant, not of the sale of a property, but of the first priority to buy the property in the event the owner sells the same. Such grant may be embodied in a separate contract, in which case it must be supported by its own consideration distinct and separate from the consideration supporting the contemplated contract, such as when it is one of the provisions in a lease contract. In entering into the contract, the lessee is in effect stating that it consents to lease the premises and to pay the price agreed upon provided the lessor also consents that, should it sell the leased property, then, the lessee shall be given the right to match the offered purchase price to buy the property at that price. Page | 183 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Note: • • • • Such grant of right of first refusal may not be unilaterally withdrawn if it stands upon valuable consideration. But like any other right, it may be waived. When a lease contains a right of first refusal, the lessor has the legal duty to the lessee not to sell the leased property to anyone at any price until after the lessor has made an offer to sell the property to the lessee and the lessee has failed to accept it. Only after the lessee has failed to exercise his right of first priority could the lessor sell the property to other buyers under the same terms and conditions offered to the lessee, or under terms and conditions more favorable to the lessor. Not Covered by Statute of Frauds Example: 1. If the lessor sold the leased premises to a third person without offering first the property to the lessee, the latter’s right of first refusal is violated. 2. If the lessor offered the property to the lessee for P1.5 Million and the latter decided not to buy the property at that price, the former cannot sell the same property to a third person at a price lower than P1.5 Million, otherwise, there will be a violation of the lessee’s right of first refusal. Distinguished from Option Option Would require a clear certainty on both the object and the cause or consideration of the envisioned contract. with another but also on terms, including the price, that obviously are yet to be later firmed up. The option granted What is involved is to the offeree is for only a right of first a fixed period and at refusal. a detrmined price. No definite period One of the parties within which the was granted a fixed leased premises will period to buy the be offered for sale subject property at to the lessee and a price certain. the price is made subject to negotiation and determined only at the time the option to buy is exercised. Right of First Refusal While the object might be made determinate, the exercise of the right would be dependent not only on the grantor’s eventual intention to enter into a binding juridical relation • • • A right of first refusal is not among those listed as unenforceable under the statute of frauds. The application of Article 1403, par. 2(e ) presupposes the existence of a perfected, albeit written, contract of sale. A right of first refusal need not be in written to be enforceable and may be proven by oral evidence. Effect of Violation of Right of First Refusal The following are the consequences of violation of the grantee’s right of first refusal: 1. If the grantor has entered into a contract with a third person: • A contract of sale entered into in violation of a right of first refusal of another person is rescissible because it is in fraud of creditor. • The status of creditors can be validly accorded to grantees of the right of first refusal for they have substantial interests that will be prejudiced by the Page | 184 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 conveyance of the property subject matter of their right of first refusal. 2. If the contract in violation of the right of first refusal is rescinded: • The grantor may now be directed to comply with his obligation to sell the property to the grantee under the same terms and conditions that it had been sold to a third person. • There should be identity of terms and conditions to be offered to the buyer holding the right of first refusal. • Restriction: • Riviera Filipina, Inc. vs Court of Appeals • The parties to the case are therefore expected, in defense to the court’s exercise of jurisdiction over the case, to refrain from doing acts which would dissipate or debase the thing subject of the litigation or otherwise render the impending decision therein ineffectual. • A right of first refusal means identity of terms and conditions to be offered to the lessee and all other prospective buyers and a contract of sale entered into in violation of right of first refusal of another person, while valid, is rescissible. Article 1381 (4) requires that any contract entered into by a defendant in case which refers to things under litigation should be with the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of a competent judicial authority. Any disposition of the thing subject of litigation or any act which tends to render inutile the court’s impending disposition in such case, sans the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of the court, is unmistakably and irrefutably indicative of bad faith. Note: Contracts Relating to Things Under Litigation • • Contracts which are rescissible due to fraud or bad faith include those which involve things under litigations, if they have been entered into by the defendant without the knowledge and approval of the litigants or of competent judicial authority. Basis: Article 1381 (4) • • It requires the concurrence of the following: 1. The defendant during the pendency of the case, enters into a contract which refers to the thing subject of litigation. 2. The said contract was entered into without knowledge and approval of the litigants or of a competent judicial authority. • Payment made in State of Insolvency • Reason: • Article 1381(4) seeks to remedy the presence of bad faith among the parties to a case and/or any fraudulent act which they may commit with respect to the thing subject of litigation. The defendant in such a case is not absolutely proscribed from entering into a contact which refer to things under litigation. If a defendant enters into a contract which conveys the thing under litigation during the pendency of the case, the conveyance would be valid, there being no definite yet coming from the court with respect to the thing subject of litigation. The absence of such knowledge or approval would not precipitate the invalidity of an otherwise valid contract. Though considered, valid, may be rescinded at the instance of the other litigants. • A debtor who is under a state of insolvency should not give undue preference to once creditor by paying only the latter’s credit to the prejudice of the others. Any payment made by an insolvent debtor of an obligation the fulfillment of which could not be compelled at the time of the payment is considered fraudulent and is, therefore, rescissible under Article 1382. Page | 185 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Other Contracts Specially Declared by Law to be Rescissible • Contracts which are specially declared by law to be subject to rescission: • Articles 1189, 1191, 1526, 1534, 1542, 1556, 1567, 1592, and 1659. Article 1383. The action for rescission is subsidiary; it cannot be instituted except when the party suffering damage has no other legal means to obtain reparation for the same. (1294) Article 1384. Rescission shall be only to the extent necessary to cover the damages caused. (n) Subsidiary Remedy • • • • • In rescission by reason of lesion or economic prejudice, the cause of action is subordinated to the existence of that prejudice, because it is the raison d’ etre as well as the measure of the right to rescind. Rescission of this kind is allowed only to the extent necessary to cover the damages caused. Only the creditor who brought the action for rescission can benefit from the rescission; those who are strangers to the cation cannot benefit from its effect, although they are creditors prior to the questioned alienation. The revocation is only to the extent of the plaintiff creditor’s unsatisfied credit; as to the excess, the alienation is maintained. Where the defendant makes good the damages cause, the action cannot be maintained or continued. The subsidiary character of the action for rescission applies only to contracts enumerated in Articles 1381 and 1382; it does not apply to rescission under Articles 1191, 1592, and 1659. Subsidiary Remedy – the exhaustion of all remedies by the prejudiced creditor to collect claims due him before rescission is resorted to. It is essential that the party asking for rescission prove that he has exhausted all other legal means to obtain satisfaction of his claim. A creditor would have a cause of action to bring an action for rescission, it is alleged that the following successive measures have already been taken: 1. Exhaust the properties of the debtor through levying by attachment and execution upon all the property by the debtor, except such as are exempt by law from execution. 2. Exercise all the rights and actions of the debtor, save those personal to him (accion subrogatoria). 3. Seek rescission of the contracts executed by the debtor in fraud of their rights (accion pauliana). Accion Pauliana presupposes the following: 1. A judgement 2. The issuance by the trial court of a writ of execution for the satisfaction of the judgement 3. The failure of the sheriff to enforce and satisfy the judgement of the court. Article 1385. Rescission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest; consequently, it can be carried out only when he who demands rescission can return whatever he may be obliged to restore. Neither shall rescission take place when the things which are the object of the contract are legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith. In this case, indemnity for damages may be demanded from the person causing the loss. (1295) Effects of Rescission • When the contract is ordered rescinded by the court, the contract is not invalidated or declared void in its inception. Page | 186 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • • It is in the annulment of a voidable contract where the contract is invalidated from its inception by the judgment of a competent court. Rescission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest. The necessary consequence of rescission is mutual restitution, that is, the parties to a rescinded contract must be brought back to their original situation prior to the inception of the contract; hence, they must return what they received pursuant to the contract. Rescission has the effect of unmaking a contract, or its undoing from the beginning, and not merely its termination. When the contract is rescinded, it is deemed inexistent, and the parties are returned to their status quo ante. It can be carried out only when the one who demands rescission can return whatever he may be obliged to restore. • In order that an action for rescission may prosper, one of the requisites is that the person demanding rescission must be able to return what he may be obliged to restore if rescission is granted by the court. Rescission cannot take place when the things which are the object of the contract are legally in the possession of third persons who did not act in bad faith. • • • • Indemnity for damages may be demanded from the person causing the loss. When it is no longer possible to return the object of the contract, an indemnity for damages operates as restitution. • As to who or which is in legal possession of a property, the registration in the Registry of Deeds of the subject property under the name of a third person indicates the legal possession of that person. Article 1385 also applies to Rescission under Article 1191 • • The requirement of mutual restitution whether the rescission is based on the grounds enumerated under Article 1381 or upon the ground established in Article 1991. Mutual restitution is also required in cases involving rescission under Article 1191. Article 1386. Rescission referred to in Nos. 1 and 2 of article 1381 shall not take place with respect to contracts approved by the courts. (1296a) Article 1387. All contracts by virtue of which the debtor alienates property by gratuitous title are presumed to have been entered into in fraud of creditors, when the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay all debts contracted before the donation. Alienations by onerous title are also presumed fraudulent when made by persons against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. The decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated, and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission. In addition to these presumptions, the design to defraud creditors may be proved in any other manner recognized by the law of evidence. (1297a) Presumption and Badges of Fraud In allowing rescission in case of an alienation by onerous title, the third person who received the property conveyed should likewise be a party to the fraud. So long as the person who is in legal possession of the property did not act in bad faith, rescission cannot take place. Presumption of Fraud In case of Gratuitous Alienation • In case of gratuitous alienation of property, the first paragraph of Article 1387 of the Civil Code provides that All contracts by virtue of Page | 187 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • which the debtor alienates property by gratuitous title are presumed to have been entered into in fraud of creditors, when the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay all debts contracted before the donation. Article 759, second paragraph, states that the donation is always presumed to be in fraud of creditors, when the time thereof the donor did not reserve sufficient property to pay his debts prior to the donation. • For the foregoing presumption of fraud to apply, it must be established that the donor did not leave adequate properties which creditors might have recourse for the collection of their credits existing before the execution of the donation. • • • Note: • In Case of Alienation by Onerous Title • • Alienations by onerous title are also presumed fraudulent when made by persons against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. For the presumption to apply, the same article state that the decision or attachment need not refer to the property alienated, and need not have been obtained by the party seeking the rescission. Alienation • • Connotes the transfer of the property and possession of lands, tenements, or other things, from one person to another. This term is particularly applied to absolute conveyance of real property and must involve a complete transfer from one person to another. On Mortgage • The execution of mortgage is not contemplated within the meaning of alienation by onerous title under said provision. • It does not contemplate a transfer or an absolute conveyance of a real property. It is an interest in land created by a written instrument providing security for the performance of a duty or the payment of a debt. It is merely a lien that neither creates a title nor an estate. For a contract to be rescinded for being in fraud of creditors, both contracting parties must be shown to have acted maliciously so as to prejudice the creditors who were prevented from collecting their claims. The presumption of fraud in case of alienations by onerous title only applies to the person who made such alienation, and against whom some judgment has been rendered in any instance or some writ of attachment has been issued. Whether the person, against whom a judgment was made or some writ of attachment was issued, acted with or without fraud, so long as the third person who is in legal possession of the property in question did not act with fraud and in bad faith, an action for rescission cannot appear. Badges of Fraud 1. The fact that the consideration of the conveyance is fictitious or is inadequate. 2. A transfer made by a debtor after suit has begun and while it is pending against him. 3. A sale upon credit by an insolvent debtor. 4. Evidence of large indebtedness or complete insolvency. 5. The transfer of all or nearly all of his property by a debtor, especially when he is insolvent or greatly embarrassed financially. 6. The fact that the transfer is made between father and son, when there are present other of the above circumstances. 7. The failure of the vendee to take exclusive possession of all the property. Note: the above enumeration is not an exclusive list. Page | 188 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Test in Determining Whether Conveyance is Fraudulent • • • • • • In determining whether or not a certain conveyance is fraudulent the question in every case is whether the conveyance was a bona fide transaction or a trick and contrivance to defeat creditors, or whether it conserves to the debtor a special right. It is not sufficient that it is founded on good considerations or is made with bona fide intent: it must have both elements. If defective in either of these, although good between the parties, it is voidable as to creditors. The test as to whether or not a conveyance is fraudulent is, does it prejudice the rights of creditors. Contracts in fraud of creditors are those executed with the intention to prejudice the rights of creditors. To creditors seeking contract rescission on the ground of fraudulent conveyance rest the onus of proving by competent evidence the existence of such fraudulent intent on the part of the debtor, albeit they may fall back on the disputable presumptions, if proper, established under Article 1387. Article 1388. Whoever acquires in bad faith the things alienated in fraud of creditors, shall indemnify the latter for damages suffered by them on account of the alienation, whenever, due to any cause, it should be impossible for him to return them. If there are two or more alienations, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively. (1298a) Liability of Third Persons Who Acquired in Bad Faith 1. If the transferee acted in good faith, the contract can no longer be rescinded even if the subsequent transferee has acted in bad faith. • Since it is no longer possible to return the object of the contract, the remedy of the injured party is indemnity for damages from the person who caused the loss, or from the person who conveyed the property to the first transferee. 2. If the first transferee acted in bad faith, as to whether rescission may prosper or not will depend on the good faith or bad faith of the subsequent transferee. If the subsequent transferee who is now in legal possession of the property acted in good faith, the contract can no longer be rescinded. • The remedy of the injured party is to recover damages from the first transferee pursuant to the first paragraph of Article 1388. 3. If the first transferee acted in bad faith, as well as the subsequent transferee, the action of rescission can prosper and the object must be returned. • If the subsequent transferee cannot return the object for any reason, then all the transferees will be liable for damages in the order of their acquisitions, the first acquirer shall be liable first, and so on successively. Article 1389. The action to claim rescission must be commenced within four years. For persons under guardianship and for absentees, the period of four years shall not begin until the termination of the former's incapacity, or until the domicile of the latter is known. (1299) Prescriptive Period Applicability of Prescriptive Period in Article 1389 • • The action to claim rescission must be commenced within 4 years. The 4-year prescriptive period in Article 1389 is applicable only to rescission as a subsidiary remedy and does not apply to rescission as a principal action under Articles 1191, 1592, and 1659. Page | 189 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • As to rescission as principal action in Articles 1191, 1592, and 1659, the prescriptive period applicable is found in Article 1144, which provides that the action upon a written contract should be brought within 10 years from the time the right of action accrues. • • • Reckoning Period of Rescission Under Article 1381 (1) and (2) • Who may Bring Action and Against Whom? The perspective period of the action for rescission based on Nos. (1) and (2) of Article 1381 does not commence to run until the domicel of the absentee is known. Reckoning Period for Accion Pauliana • The law is silent as to when the prescriptive period would commence to run. General Rule: from the moment the cause of action accrues, applies. The following successive measures must be taken by a creditor before he may bring an action for rescission of an allegedly fraudulent contract: 1. Exhaust the properties of the debtor through levying by attachment and execution upon all the property of the debtor, except such as are exempt by law from execution. 2. Exercise all the rights and actions of the debtor, save those personal to him (accion subrogatoria). 3. Seek rescission of the contracts executed by the debtor in fraud of their rights (accion pauliana) • • The date of the decision of the trial court against the debtor is immaterial. What is important is that the credit of the plaintiff antedates that of the fraudulent alienation by the debtor of his property. The decision of the trial court against the debtor will retroact to the time when the debtor became indebted to the creditor. An accion pauliana accrues only when the creditor discovers that he has no longer legal remedy for the satisfaction of his claim against the debtor other than accion pauliana. As long as the creditor still has a remedy at law for the enforcement of his claim against the debtor, the creditor will not have any cause of action against the creditor for rescission of the contracts entered into by and between the debtor and another person or persons. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 The action for rescission may be brought by: 1. The person who is injured by the rescissible contract, that is, the ward or absentee, the creditors damages or the plaintiff in case a thing in litigation is alienation by defendant. 2. The heirs of the above persons. 3. The creditors of the aforesaid perons by virtue of Article 1177. The action may be brought against the following: 1. The author of the injury and his successors in interest. 2. Third persons who have acquired in bad faith the property alienated in fraud of creditors. CHAPTER 7 Voidable Contracts Article 1390. The following contracts are voidable or annullable, even though there may have been no damage to the contracting parties: (1) Those where one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract; (2) Those where the consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. These contracts are binding, unless they are annulled by a proper action in court. They are susceptible of ratification. (n) Voidable Contract • Has all the essential elements of a contract but the consent given is defective because of Page | 190 • • • • want of capacity or vitiation thereof by reason of mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. Are existent, valid, and binding, although they can be annulled because of want of capacity or the vitiated consent of one of the parties. Before such annulment, they are considered effective and obligatory between parties. It is valid until it is set aside and its validity may be assailed only in an action for that purpose. They can be confirmed or ratified. Characteristics of Voidable Contract 1. It is existent, valid, and binding and produces all its civil effects, until it is set aside by a final judgment of a competent court in an action for annulment. 2. However, it suffers from a defect in the form of vitiation of consent by lack of legal capacity of one of the contracting parties, or by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. 3. It may be rendered perfectly valid by ratification, which can be expressed or implied, such as by accepting and retaining the benefits of a contract. 4. It is also susceptible of convalidation by prescription since the action for the annulment of contract prescribes in four years. 5. It cannot be attacked collaterally. Its validity can only be assailed directly either by an action for that purpose or by way of a counter-claim for that purpose. Example: An action to recover a parcel of land upon the theory that the plaintiff was the owner because the conveyance made by his father was null and void due to fraud, the Court ruled that the alleged fraudulent deed must first be set aside in a special action for that purpose. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Voidable Contracts The court has first to set aside and render ineffective by its judgment the contract which therefore is valid and producing legal effect, before the defendant can be exempt from compliance therewith; hence, the attack against its validity must be directly made in an action or in a counterclaim for that purpose, with the consequence flowing from the declaration of nullity. The annulment is by a proper action in court. Void Contracts The court merely declares the contract as void and inexistent, which is its condition from the very beginning, and therefore the attack against its validity can be made collaterally or indirectly. The declaration of nullity may be by action or defense. Distinguished from Rescissible Contract Rescissible Voidable Contract Contract Both contain all the essential elements of a contract and both are existent, valid and binding until they are set aside by a final judgement of the court in an action for rescission or for annulment. The action for rescission or annulment is subject to a four-year prescriptive period. The defect consists The defect consists of lesion or in vitiation thereof economic prejudice. by reason of mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence or fraud. The defects are not The defect may be subject to ratified. ratification The remedy of the The remedy is an injured party is an action for annulment. Page | 191 action for rescission. Even a third person who is prejudiced by the contract may assail it. When a contract is rescinded by the court, it is not invalidated or declared void in its inception but simply deemed inexistent or abrogated from the beginning. Third person assail its validity. When it is annulled, the contract is invalidated from the very beginning. Annulment distinguished from Rescission Annulment Declares the inefficiency which the contract already carries in itself. The defect is intrinsic because it consists of a vice which vitiates consent. The annullability of the contract is based on the law. Not only a remedy but a sanction. The direct influence of the public interest is noted. The contract is annullable even if there is no damage or prejudice. The nullity is based on a vice of the contract which invalidates it. The contract is susceptible of ratification. Rescission Merely produces the inefficacy, which did not exist essentially in the contract. The defect is external because it consists of damage or prejudice either to one of the contracting parties or to a third person. The rescissibility of the contract is based on equity. Merely a remedy. Private interests predominate. The contract is not rescissible if there is no damage or prejudice. Is compatible with the perfect validity of the contract. May be invoked May be invoked only by a either by a contracting party. contracting party or by a third person who is prejudiced. The action is a The action is a principal remedy. subsidiary remedy. Annulment Distinguished Under Article 1191 Annulment Under Art. 1390 One of the essential elements to a formation of a contract, which is consent, is absent. The defect is already present at the time of the negotiation and perfection stages of the contract. from Rescission Rescission Under Art. 1191 All the elements to make the contract valid are present. The defect is in the consummation stage of the contract when the parties are in the process of performing their respective obligations. Grounds for Annulment 1. Where one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract. 2. Where the consent is vitiated by mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud. • If the ground is want of capacity, it is necessary that only of the parties must be incapable of giving consent because if both arties are incapable of giving consent to a contract, the contract is not merely voidable but unenforceable. The contract is NOT susceptible of ratification. Page | 192 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Article 1391. The action for annulment shall be brought within four years. 4. If the ground for annulment is want of capacity other than minority, from the time the guardianship ceases. This period shall begin: In cases of intimidation, violence or undue influence, from the time the defect of the consent ceases. In case of mistake or fraud, from the time of the discovery of the same. And when the action refers to contracts entered into by minors or other incapacitated persons, from the time the guardianship ceases. (1301a) Prescriptive Period • An action for the annulment of a voidable contract prescribes in four years. The period commences to run, as follows: 1. If the ground for annulment is vitiation of consent by intimidation, violence, or undue influence, the four-year period starts from the time such defect ceases. • The running of this prescriptive period cannot be interrupted by an extrajudicial demand made by the party whose consent was vitiated. 2. If the ground for annulment is vitiation of consent by mistake of fraud, the four-year period starts from the time of the discovery of the same. • Article 1392. Ratification extinguishes the action to annul a voidable contract. (1309a) Article 1393. Ratification may be effected expressly or tacitly. It is understood that there is a tacit ratification if, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. (1311a) Article 1394. Ratification may be effected by the guardian of the incapacitated person. (n) Article 1395. Ratification does not require the conformity of the contracting party who has no right to bring the action for annulment. (1312) Article 1396. Ratification cleanses the contract from all its defects from the moment it was constituted. (1313) Confirmation • Acknowledgement or Recognition • If the fraudulent conveyance is registered in the Register of Deeds, the discovery of fraud is reckoned from the time the document was registered in the Register of Deeds in view of the rule that registration is notice to the whole world. 3. If the ground for annulment is want of capacity by reason of minority, the four-year period starts when the minor reaches the age of majority, or when he attains the age of 18 years. Refers to the act of purging a voidable contract of its defect through the renunciation of the action of nullity made by the person who can invoke the vide or defect of the contract. Is the act of remedying the deficiency of proof as when a contract falling under the Statute of Frauds is made orally but later on put in writing, or when a private document is converted into a public instrument. Ratification • Is the act of curing the defect of a contract entered into in the name of another person without authority or in excess of authority by the approval thereof. Page | 193 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • Whether the contract is voidable or unenforceable, the manner of curing the defect is altogether referred to as ratification. Refers to the act or means by which efficacy is given to a contract which suffers from a vice of curable nullity. It may be effected expressly or tacitly. Tacit Ratification • If, with knowledge of the reason which renders the contract voidable and such reason having ceased, the person who has a right to invoke it should execute an act which necessarily implies an intention to waive his right. Implied or Tacit Ratification • May take diverse forms, such as by silence or acquiescence; by acts showing approval or adoption of the contract; or by acceptance and retention of benefits flowing therefrom. Example: 1. Viloria vs Continental Airlines, Inc. – The Court ruled that by pursuing the remedy of rescission under Art. 1191, there is an implied admission of the validity of the subject of the contracts, thereby forfeiting the right to demand annulment. Rescission Under Article 1191 The defect is the consummation stage of the contract when the parties are in the process of performing their respective obligations. Annulment The defect is already present at the time of the negotiation and perfection stages of the contract. 2. When the contract entered into by a person during his minority but he failed to repudiate it promptly upon reaching his majority and instead disposed of the greater part of the proceeds after he became of age and after he had knowledge of the facts upon which he sought to disaffirm the agreement. It was ruled that the contract was tacitly ratified. Requisites of Ratification 1. The contract has all the essential requisites, but it is tainted with a vice which is susceptible of being cured. 2. It should be effected by the person who is entitled to do so under the law. • The conformity of the contracting party who has no right to bring the action for annulment is not required. 3. It should be effected with the knowledge of the vice or defect. 4. The cause of the nullity or defect should have already disappeared. Article 1397. The action for the annulment of contracts may be instituted by all who are thereby obliged principally or subsidiarily. However, persons who are capable cannot allege the incapacity of those with whom they contracted; nor can those who exerted intimidation, violence, or undue influence, or employed fraud, or caused mistake base their action upon these flaws of the contract. (1302a) Who may Bring Action for Annulment? To have the personality to bring an action for the annulment of a voidable contract: 1. He must have an interest in the contract. • He must be bound by the contract either principally or subsidiarily, but including his heir to whom the right and obligation arising from the contract are transmitted. • If no such rights, actions or obligations have been transmitted to the heir, the latter cannot bring an action to annul the contract in representation of the contracting party who made it. Exception: a person who is not obliged principally or subsidiarily in a contract may exercise an action for nullity of the contract “if he is prejudiced in his Page | 194 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 rights with respect to one of the contracting parties, and can show the detriment which could positively result to him from the contract in which he had no intervention.” 2. He must be the victim and not the party responsible for the defect. • • Persons sui juris cannot avail themselves of the incapacity of those with whom they contracted in order to annul their contract. The person who exerted intimidation, violence, or undue influence, or employed fraud, or caused mistake cannot base his action for the annulment of contracts upon these flaws of the contract, following the principle that he who comes to court must do so with clean hands. Article 1398. An obligation having been annulled, the contracting parties shall restore to each other the things which have been the subject matter of the contract, with their fruits, and the price with its interest, except in cases provided by law. In obligations to render service, the value thereof shall be the basis for damages. (1303a) Article 1399. When the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the parties, the incapacitated person is not obliged to make any restitution except insofar as he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. (1304) Article 1400. Whenever the person obliged by the decree of annulment to return the thing can not do so because it has been lost through his fault, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. (1307a) Article 1401. The action for annulment of contracts shall be extinguished when the thing which is the object thereof is lost through the fraud or fault of the person who has a right to institute the proceedings. If the right of action is based upon the incapacity of any one of the contracting parties, the loss of the thing shall not be an obstacle to the success of the action, unless said loss took place through the fraud or fault of the plaintiff. (1314a) Article 1402. As long as one of the contracting parties does not restore what in virtue of the decree of annulment he is bound to return, the other cannot be compelled to comply with what is incumbent upon him. (1308) Effects of Annulment • • • If voidable contract is annulled by a final judgment of a competent court, the contract is invalidated from the very beginning. The nullity of voidable contracts can only be produced by a judgement of the court. In the absence of such judgment, the contract is regarded as valid and obligatory between the parties. Mutual Restitution • Upon annulment the parties should be restored to their original position by mutual restitution. Exception to Mutual Restitution • • • • The parties to a contract that has been annulled are obliged to restore to each other the things which have been the subject matter of the contract will not apply “if the defect of the contract consists in the incapacity of one of the parties and the incapacitated person has not been benefited by the thing or the price received by him. The obligation of the incapacitated person to make restitution in only to the extent that he has been benefited by the thing or price received by him. The burden to prove such benefit is incumbent upon the party who is sui juris and the mere delivery of the thing to the incapacitated person is not of such benefit. When the action for annulment is based upon the incapacity of the plaintiff, the loss of the thing during the plaintiff’s incapacity shall not Page | 195 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • be an obstacle to the success of the action, nor does it render him liable to for the price or value of the thing, inasmuch as he has not been benefited by it. If the loss took place through the fraud or fault of the plaintiff, his action for annulment cannot prosper. Effect of Loss of Object of Contract 1. If the thing is lost by the party who has the right to annul the contract (the plaintiff) a. The action for annulment is extinguished if the thing has been lost through his fraud or fault, even if the ground for annulment is the incapacity of the plaintiff. b. The action for annulment cans till prospers of the thing has been lost not by reason of the plaintiff’s fraud or fault. • If the ground for annulment is the incapacity of the plaintiff, the incapacitated person has no obligation to pay the value of the thing because he has not been benefited by it. • If the ground for annulment is other than the incapacity of the plaintiff, the plaintiff must pay the value of the thing at the time of the loss but without the obligation to pay interest thereon. 2. If the thing is lost by the party who has no right to annul the contracts, the action for annulment can still prosper even if the loss was without his fault. • • His obligation is to pay the value of the thing at the time of the loss, but without interest thereon. If the thing has been lost through his fault, he shall return the fruits received and the value of the thing at the time of the loss, with interest from the same date. Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 CHAPTER 8 Unenforceable Contracts (n) Article 1403. The following contracts unenforceable, unless they are ratified: are (1) Those entered into in the name of another person by one who has been given no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers; (2) Those that do not comply with the Statute of Frauds as set forth in this number. In the following cases an agreement hereafter made shall be unenforceable by action, unless the same, or some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent; evidence, therefore, of the agreement cannot be received without the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents: (a) An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; (b) A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another; (c) An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; (d) An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose Page | 196 account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum; (e) An agreement for the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein; aside by a intermediate ground competent court. between the voidable and the void contract. Void Contracts ( f ) A representation as to the credit of a third person. (3) Those where both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract. Unenforceable Contracts • Are those which cannot be enforced by a proper action in court, unless they are ratified, because either they are entered into without or in excess of authority or they do not comply with the statute of frauds or both of the contracting parties do not possess the required legal capacity. Nature and Characteristics • • An unenforceable contract has all the essential requisites enumerated in Article 1318; hence, it is a perfected contract. It is also a valid contract although it cannot be sued upon or be enforced by a proper action in court because of its defect. The defect of the contract consists of either: 1. It is entered into without or in excess of authority. 2. It does not comply with the Statute of Frauds. 3. Bot of the contracting parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract. • Unenforceable contract is not binding or obligatory between the parties, unless the contract is ratified. Rescissible and Unenforceable Voidable Contracts Contracts Are both obligatory More defective and unless they are set occupies an Unenforceable Contracts Not susceptible to Can be ratified. ratification. • • • • An unenforceable contract, the effect is purely a matter of defense. As long as it is not ratified, the defect of the contract is of a permanent nature. The mere lapse of time cannot give efficacy to such a contract. The defect is such that it cannot be cured except by the subsequent ratification of the unenforceable contract by the person in whose name the contract was executed. Note: The defense that the contract is unenforceable is available only to the contracting parties. Basis: unenforceable contracts cannot be assailed by third persons (Art. 1408) Three kinds of Unenforceable Contracts: 1. Contracts entered into in the name of another without the authority or in excess of authority. 2. Contracts which do not comply with the Statute of Frauds. 3. Contracts where both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract. Article 1404. Unauthorized contracts are governed by article 1317 and the principles of agency in Title X of this Book. Unauthorized Contracts • Unenforceable, not void. Page | 197 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Basis: • • authorization therefor unless he has by law a right to represent the latter. First paragraph of Article 1403 Article 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. • Note: • • Article 1910. xxx as for any obligation wherein the agent has exceeded his power, the principal is not bound except when he ratifies it expressly or tacitly. The pronouncement in Delos Reyes and Heirs of Sevilla and Gochan, appear to be erroneous, as they run counter to the explicit provisions of Articles 1317 and 1403, paragraph 1 which classifies unauthorized contracts as “unenforceable” and not void ab initio. The absence of consent of the alleged principal does not justify the characterization of the contract as void ab initio because Congress was fully aware if such absence in cases of unauthorized contracts and yet Congress chose to classify the contract merely unenforceable and not void and gave the alleged principal the opportunity to ratify the defect by subsequently approving the contract entered into in his name. Note: • • In case of unauthorized contract, it is obvious that no consent has been given by the alleged principal. The absence of the principal’s consent does not make the contract void or inexistent, even as to the alleged principal who has not given his authorization. Rule: Under the provisions of Article 1317 and 1403, paragraph 1, the contract is classified merely as “unenforceable” and not “void ab initio” Delos Reyes vs Court of Appeals, Heirs of Sevilla vs Sevilla, and Felix Gochan and Sons Realty Corp. vs Heirs of Baba • • The court classified the contract as void ab initio and not merely unenforceable when the agreement is entered into by one in behalf of another who has never given him authorization. Reason of the Court: there is said to be no consent, and consequently, no contract when the agreement is entered into by one in behalf of another who has never given him Why is it important to properly characterized the status of Contracts entered into by one in behalf of another who has never given him authorization as merely unenforceable and not void ab initio? Answer: An unenforceable contract can be ratified while a void contract is not susceptible to ratification. In unenforceable contract, once the contract is ratified, the effect of ratification retroacts to the day when the contract was entered into by the agent and cleanses the contract from all its defects from the moment it was constituted, thereby rendering the contract obligatory. • • Article 1390 (1) is inapplicable to unauthorized contracts as said article contemplates the incapacity of the party to give consent to a contract and not to lack of authority, which is governed by Articles 1403 (1), 1404, and 1317. The failure of the agent to obtain authority from his alleged principals did not result in his incapacity to give consent so as to render the contract voidable, but rather, in rendered the contract valid but unenforceable against the alleged principals for having been entered into without their authority. Page | 198 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Rule Different in Agency to Sell Land • • If the unauthorized contracts deal with the sale of a parcel of land or any interest therein, the applicable provision is Article 1874 of the Civil Code: o Article 1874. When a sale of a piece of land or any interest therein is through an agent, the authority of the latter shall be in writing; otherwise, the sale shall be void. An unauthorized contract involving the sale of a parcel of land is not merely unenforceable but void ab initio. 2. By acceptance of benefits under the contract. • • • In this case, the contract is no longer executory and, therefore, the Statute does not apply. This rule is based upon the familiar principle that one who has enjoyed the benefits of a transaction should not be allowed to repudiate its burden. It is also an indication of a party’s consent to the contract as when he accepts partial payment or delivery of the thing sold thereby precluding him from rejecting its binding effect. How Ratified Right of a party where contract enforceable • In case of an unauthorized contract, the defect of the contract is cured in whose name the contract was executed subsequently gives his or her approval. Article 1405. Contracts infringing the Statute of Frauds, referred to in No. 2 of article 1403, are ratified by the failure to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the same, or by the acceptance of benefit under them. Article 1406. When a contract is enforceable under the Statute of Frauds, and a public document is necessary for its registration in the Registry of Deeds, the parties may avail themselves of the right under Article 1357. Modes of Ratification under the Statute The ratification of contracts infringing the Statute of Fraud may be effected in two ways: 1. By failure to object to the presentation of oral evidence to prove the contract. • • The failure to object timely amounts to a waiver and makes the contract as binding as if it had been reduced to writing. Cross examination of a witness testifying orally on the contract with respect to matters inadmissible under the Statute amounts to failure to object. 1. A party to an oral sale of real property cannot compel the other to put the contract in a public document for purposes of registration because it is unenforceable unless, of course, it has been ratified. 2. Similarly, the right of one party to have the other execute a public document is not available in a donation of realty when it is in a private instrument because the donation is void. Note: See attached file Article 1407. In a contract where both parties are incapable of giving consent, express or implied ratification by the parent, or guardian, as the case may be, of one of the contracting parties shall give the contract the same effect as if only one of them were incapacitated. If ratification is made by the parents or guardians, as the case may be, of both contracting parties, the contract shall be validated from the inception. Article 1408. Unenforceable contracts cannot be assailed by third persons. Contracts where Both parties are Incapacitated • Where only one of the parties is incapable of giving consent to a contract, the contract is Page | 199 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • • • merely voidable; but if both parties are incapable of giving consent to a contract, the contract is not voidable but unenforceable. In either case, the contract may be ratified. In a contract which is unenforceable because both parties are incapacitated, the ratification on the part of one of the contracting parties “shall give the same effect as if only one of them were incapacitated, thereby making the contract merely voidable. If ratification is made on the part of both parties, the contract shall be validated from the inception. If the contract is unenforceable, the defect of the contract can be ratified in the same manner that voidable contract is ratified. Implied or tacit ratification may take diverse forms, such as: a. By silence or acquiescence b. By acts showing approval or adoption of the contract c. By acceptance and retention of benefits flowing therefrom. Chapter 9 Void or Inexistent Contracts Void or Inexistent Contracts Is equivalent to nothing; it produces no legal effect whatsoever in accordance with the principle “quod nullum est nullum producit effectum.” Contains all the essential requisites but it is invalid from the very beginning either because: Its causes, object or purposes is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy; Its object is outside the commerce of men; It contemplates an impossible service; Or it is expressly prohibited or declared void by law. Distinction Between Void and Inexistent Contracts • • One which lacks one or more essential requisites of a contract enumerated in Article 1318 of the Civil Code. o • The two terms are interchangeable. Void or inexistent contract is often defined in jurisprudence as one which has no force and effect from the very beginning, as if it had never been entered into, and which cannot be validated either by time or ratification. The in pari delicto doctrine applies only to contracts with illegal consideration or subject matter, whether the attendant facts constitute an offense or misdemeanor or whether the consideration involved is merely rendered illegal. Example: Void Contract Inexistent Contract Also referred to as The principle of in inexistent from the pari delicto is not beginning. applicable. Hence, the principle is not applicable to fictitious or simulated contracts. • • A contract without any cause or consideration, or absolutely simulated or fictitious, is in reality non-existent. A contract with an illegal cause or subject matter, for purposes of applying the principle of in pari delicto, is not inexistent. Page | 200 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Concept and Characteristics Inexistent Contracts of Void or 1. General Rule: they produce no legal effects whatsoever in accordance with the principle “quod nullum est nullum producit effectum.” Exception: when the void contract has already been performed and the principle of in pari delicto is applied. • The guilty parties to an illegal contract cannot recover from one another and are not entitled to an affirmative relief. 2. They are not susceptible of ratification. 3. The right to set up the defense of inexistent or absolute nullity cannot be waived or renounced. 4. The action or defense for the declaration of their inexistent or absolute nullity is imprescriptible. • • The defect of a void or inexistent contract is permanent. The right to have a contract declared void ab initio may be barred by laches although not barred by prescription. waived renounced. or inexistence or absolute nullity cannot be waived or renounced. The action to annul The action or is subject to a 4- defense for the year prescriptive declaration of the period. inexistence or absolute nullity of a void or inexistent contract is imprescriptible. It is extended to The right to set up third persons who the nullity is not are directly affected limited to the by the contract. parties. If the contract is The remedy is an voidable, the action for remedy is declaration of nullity annulment of the of contract. contract. Article 1409. The following contracts inexistent and void from the beginning: are (1) Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy; 5. The inexistence or absolute nullity of a contract cannot be invoked by a person whose interest are not directly affected. (2) Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious; Voidable Contract vs Void or Inexistent Contract (3) Those whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction; Voidable Contract Considered effective and obligatory between parties, until it is set aside by a final judgement of a competent court in an action for annulment. Susceptible of ratification The right to annul the contract can be Void or Inexistent Contract Produces no legal effects whatsoever in accordance with the principle “quod nullum est nullum producit effectum.” Not susceptible of ratification The right to set up the defense for the declaration of the (4) Those whose object is outside the commerce of men; (5) Those which impossible service; contemplate an (6) Those where the intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained; (7) Those expressly declared void by law. prohibited or Page | 201 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 These contracts cannot be ratified. Neither can the right to set up the defense of illegality be waived. CONTRACTS DECLARED VOID OR INEXISTENT In General - A contract is void from the very beginning when: (1) Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy; (2) Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious; (3) Those whose cause or object did not exist at the time of the transaction; (4) Those whose object is outside the commerce of men; (5) Those which contemplate an impossible service; (6) Those where the intention of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot be ascertained; (7) Those expressly prohibited or declared void by law. When Cause, Object, or Purpose Is Illegal: a. Illegality of Cause o Cause is ordinarily different from motive and, as a rule, the motive or particular purpose of a party in entering into a contract does not affect the validity nor the existence of the contract. o Cause is the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into it. o Cause is the immediate, direct and proximate reason which justifies the creation of an obligation through the will of the contracting parties. o Motive on the other hand is the particular reason of a contracting party which does not affect the other party. EXCEPTION: § motive may be regarded as causa when it predetermines the purpose of the contract § when the realization of such motive or particular purpose has been made a condition upon which the contract is made, a condition which the contract is made to depend, then the motive becomes the cause. o When motive and cause blend to such a degree, and the motive is unlawful, then the contract entered into is null and void. b. Object or Subject-Matter Is Unlawful o As a rule, all forms of gambling are illegal. o The only form of gambling allowed by law is that stipulated under Presidential Degree No. 1869, which gave PAGCOR its franchise to maintain and operate gambling casinos. o Thus, even the object of the contract is gambling outside the purview of PD 1869, the same is illegal and, therefore, void. o Thus, in Yun Kwan Byung vs PAGCOR, it was held that courts will not enforce debts arising from gambling. • Ruling: The SC ruled that the Junket Agreement is void, gambling between the hunket player and the junket operator under such ageement is illegal and may not be enforced by the courts • Citing Article 2014 of the NCC, the SC ruled that no action can be maintained by the winner for the collection of what he has won in an illegal gambling c. Illegal Purpose o For example, a partnership must have a lawful object or purpose, and must be established for the common benefit or interest of the partnership. o When the partnership has unlawful object or purpose, the contract of partnership is void. o When such unlawful partnership is dissolved by a judicial decree, the profits shall be confiscated in favor of the State, without prejudice to the provisions of the Penal Code governing the confiscation of the instrument and effects of a crime. d. Contrary to Public Policy, Good Customs Or Morals o In order to declare a contract void as against public policy, a court must find that the contract as to consideration of the thing to be done, contravenes some established interest of society, or is inconsistent with sound policy and good moral or tends clearly to undermine the security of individual rights o Must be shown that the object, cause or purpose thereof contravenes the generally accepted Page | 202 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 principles of morality which have received some kind of social and practical confirmation. ABSOLUTELY SIMULATED OR FICTITIOUS CONTRACTS - Such contracts are void. - An absolute simulation, there is a colorable contract but has no substance as the parties have no intention to be bound by it. - An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void, and the parties may recover from each other what they may have given under the contract. - In Absolute Simulation, there appears to be a valid contract but there is actually none because the element of consent is lacking. - Examples: o Where a person, in order to place his property beyond the reach of his creditors, simulates a transfer of it to another, he does not really intend to divest himself of his title and control of the property; hence, the deed of transfer is a sham. o A contract of purchase and sale is void and produces no effect whatsoever where it appears that the same is without cause or consideration which should have been the motive thereof, or the purchase price which appears thereon as paid but which in fact has never been paid by the purchaser to the vendor. CAUSE OR OBJECT DID NOT EXIST AT ATIME OF TRANSACTION - o Lack of an object certain at the time of the transaction o Contract of lease – void for having an inexistent cause Ballesteros vs Abion: In a lease contract over real property, the object of the contract is the leased premises. As its cause, the payment of the rentals is the cause on the part of the lessor, while the delivery of the leased premises is the cause on the part of the lessee. Therefore, the leased premises is both the object of the contract and the cause in so far as the lessee is concerned. Hence, when the lessor does not have the right to lease the premises, both the object of the contract and the cause (as to the lessee) do not exist at the time of the transaction, making the contract void pursuant to the third paragraph of Article 1409. Double Donation • Article 1409(3) will also be applicable • As a mode of acquiring and transmitting ownership, a donation results in an effective transfer of title over the property from the donor to the donee and once a donation is accepted, the donee becomes the absolute owner of the property donated. • Hence, a second donation of the same property by the same donotr to another donee is a void or inexistent contract under Article 1403(3) for lack of object vertain at the time of the transaction. The same principle is also applicable to a donation of a future property. • Under Article 751, donations cannot comprehend future property. The same article defines future property as anything which the donor cannot dispose of a the donation. • In other words, the law requires that the donor be the owner of the property donated at the time of the donation, otherwsie, such donation is void under Article 1409(3) for lack of an object certain at the time of the transaction. Contract of Sale • The rule is different however, in a contract of sale • Ownership by the seller of the thing sold at the time of the perfection of the contract of sale is not an element for its perfection. • What the law requires is that the seller has the right to transfer ownership at the time the thing sold is delivered • Perfection per se does not transfer ownership which occurs upon the actual or constructive delivery of the thing sold. • Thus, a perfected contract of sale cannot be challenged on the ground of nonownershup on the part of the seller at the time of its perfection; • Hence the sale is still valid • Unlike in an ordinary donation, where the law requires the donor to have owernship of the Page | 203 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • • thing or the real right he donates at the time of its perfection since a donation constitutes a mode, not just a title in an acquisition and transmission of ownership; in a contract of sale, the law does not require the seller to be the owner of the thing sold at the time of the sale because sale is not a mode, but merely a title. Sale by itself does not transfer or affect ownership; the most that sale does is to create the obligation to transfer ownership. It is a tradition or delivery, as a consequence of sale, that actually transfers ownership. OBJECT OUTSIDE THE COMMERCE OF MEN IMPOSSIBLE SERVICE - Any contract which contemplates an impossible service is void or inexistent - Based on the maxim impossibilum nilla obligatio est (there is no obligation to do impossible things) - May either be absolute when nobody can perform it - Absolute impossibility nullifies the contract - Relative impossiblity – when it cannot be performed because of the special conditions or qualifications of the obligor. - The effect of a relative impossibility depends on whether the same is temporary or permanent. - If temporary – it will not nullify the contract - If permanent – nullifies the contract. - In case of relative impossibility, the debtor becomes liable for damages if he cannot perform the undertaking. - Nool vs CA o Seller can no longer deliver the object of the sale to the buyers, as when the buyers themselves have acquired title and delivery thereof from the rightful owner, the contract may be deemed to be inoperative and by analogy fall under Article 1409(5) - It must be pointed out that the defect of a void or inexistent contract must be present from the very beginning. - For Article 1409(5) to apply, it is essential that the impossibility of the service contemplated by the contract must already be present at its inception in order for it to be classified as void or inexitent. - If the impossibility of service will only superervene during the consummation stage, the contract is deemed valid and the debot will only be released from his obligation pursuant to Article 1266 of the NCC o Art. 1266 – The debtor in obligations shall also be released when the prestation becomes legally or physically impossible without the fault of the obligor. - Additionally, the provision of Article 1409(5) is applicable only to obligations to do, hence, inapplicable to a contract of sale which creates an obligation to give. - The Nool case could have been decided without the need to declare void the contract of sale between the Spouse Conchita Nool and Gaudencio Almonera and Anacleto Nool - Since Anacleto Nool was able to purchase the property form the DBP and not from the Spouses Conchita Nool and Gaudencio Almonera, the latter are note entitle d to exercise a right of repurchase INTENTION AS TO PRINCIPLA OBJECT CANNOT BE ASCERTAINED - Article 1349. The object of every contract must be determinate as to its kind. The fact that the quantity is not determinate shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract, provided it is possible to determine the same, without the need of a new contract between the parties. - It is enough that the object is determinable in order for it to be considered as certain. - If the intetntion of the parties relative to the principal object of the contract cannot, however, be ascertained, the contract is void or inexistent according to Article 1409(6) of the NCC. - The same rule is echoed in Article 1378, paragraph 2 of the same Code which states that “if the doubts upon the principal object of the contract in such a way that it cannot be known what may have been the intention or will of the parties, the contract shall be null and void. EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED OR DECLARED VOID BY LAW - Contracts which are expressly prohibited or declared void by law are also void or inexistent (Article 1409(7)) - This is contemplated by Article 5 of the sam Code which states that “acts executed against the provisions of mandatory or prohibitory laws shall be void, except when the law itself authorizes their validity.” Examples: Page | 204 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. Those contracts which failed to comply with the formalities required by law for their validity 2. A contract that violates the principle of mutuality of contracts 3. Donations between spouses during the marriage and between those living together as husband and wife 4. Any dispotition or encumbrance of absolute community property or conjugal partnership property without authority of the court or written consent of the other spouse 5. Any dispotition or encumbrance of the absolute community property or conjugal partnership property of the terminated marriage without a pervious liquidation of the propert regime within one year from the death of the deceased spouse 6. Any agreement which contravenes the mandatory awarding of sole parental custody to the mother under the second paragraph of Article 213 of the Family Code 7. Any sale in violation of Articles 1490 and 1491 of the NCC 8. Any stipulation which contravenes the prohibition against pactum commissorium 9. A stipulation forbidding the owner from alienating the immovable mortgaged Article 1410. The action or defense for the declaration of the inexistence of a contract does not prescribe. Action or Defense For Declaration of Nullity • Imprescriptible o GR: the action or defense for the declaration of inexistence or absolute nullity of a void or inexistent contract is imprescriptible. o However, the prevailing doctrine is that the right to have a declared contract declared void ab initio may be barred by laches although not barred by prescription. o Laches v Prescription (MWSS v CA) • Prescription is concerned with the fact of delay, Laches is concerned with the effect of delay. • Prescription is a matter of time, laches is principally a question of inequity of permitting a claim to be enforced, this inequity being founded on some parties. • Prescription is statutory; laches is not • Laches applies in inequity, whereas prescription applies at law. • o Prescription is based on fixed-time; laches is not For laches to apply, requires the concurrence of the following: • Conduct on the part of the defendant, or one under whom he claims, giving rise to the situation that led to the complaint and for which the complaint seeks a remedy; • Delay in asserting the complainant's right, having had knowledge or notice of the defendant's conduct and having been afforded an opportunity to institute a suit; • Lack of knowledge or notice on that part of the defendant that the complainant would assert the right on which he bases his suit; and • Injury or prejudice to the defendant in the event relief is accorded to the complainant, or the suit is not held barred. Action to Declare Nullity of Contract, When Necessary o Art 1410 can be set up either by way of an action or by way of defense. o As a rule, no need of an action to set aside a void or inexistent contract o Thus, if the void contract is still fully executory, no party need bring an action to declare its nullity considering that no affirmative relief is to be prayed from the court. o But, if any party should bring an action to enforce the void contract, the other party can simply set up the nullity as defense. o On the other hand, if void contract has already been performed, an action to declare the non-existence of the contract can be maintained for the purpose of recovering what has been given by virtue of that contract. o Although a void contract has no legal effects even if no action is taken to set it aside, when any of its terms have been performed, an action to declare its inexistence is necessary to allow restitution of what has been given under it. o This action does not prescribe. o Rationale: Nobody can take the law into his own hands; hence, the intervention of the competent court is necessary to declare the Page | 205 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 absolute nullity of the contract and to decree the restitution of what has been given under it. Distinguished From Action For Annulment o To annul means to reduce to nothing; annihilate; obliterate; to make void or no effect; to nullify; to abolish to do away with. o Hence a voidable contract presupposes that is subsists but later ceases to have legal effect when it is terminated through a court action. o In annulment, it is the judgment of the court that produces the invalidity of the contract. o On the other hand, an action for declaration of nullity presupposes a void contract or one where all of the requisites prescribed by law for contracts are present but the cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. o Such contract, as a rule, produces no legal binding effect even if it is not set aside by direct legal action. o Judgement is merely declaratory or confirmatory of the existence of a state of nullity that is already present from the beginning. Article 1411. When the nullity proceeds from the illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and the act constitutes a criminal offense, both parties being in pari delicto, they shall have no action against each other, and both shall be prosecuted. Moreover, the provisions of the Penal Code relative to the disposal of effects or instruments of a crime shall be applicable to the things or the price of the contract. This rule shall be applicable when only one of the parties is guilty; but the innocent one may claim what he has given, and shall not be bound to comply with his promise. (1305) Article 1412. If the act in which the unlawful or forbidden cause consists does not constitute a criminal offense, the following rules shall be observed: (1) When the fault is on the part of both contracting parties, neither may recover what he has given by virtue of the contract, or demand the performance of the other's undertaking; (2) When only one of the contracting parties is at fault, he cannot recover what he has given by reason of the contract, or ask for the fulfillment of what has been promised him. The other, who is not at fault, may demand the return of what he has given without any obligation to comply his promise. (1306) Principle of In Pari Delicto Rules in Cases of Illegal Contracts o Art 1411 and 1412 covers cases where the cause or object thereof is unlawful. o Art 1411, the act constitutes a criminal offense o Art 1412, the act does not constitute a criminal offense o The governing rules will depend on whether a party or both parties are at fault • Where Both Parties Are at Fault (in Pari Delicto) o Statement of Principle of In Pari Delicto • Ex dolo malo non oritur actio (no right of action can have its origin in fraud) • In pari delicto potior est condicio defendentis (when the parties are equally at fault, the defendant’s position is more compelling) • The law will not aid either party to an illegal agreement. • In pari delicto • Is a universal doctrine which holds that no action arises, in equity or at law, from an illegal contract; no suit can be maintained for specific performance, or to recover the property agreed to be sold or delivered, or the money agreed to be paid, or damages for its violation; and where the parties in pari delicto, no affirmative relief of any kind will be given to one against the other. • Premise on two grounds • First, the courts should not lend their good offices to mediating disputes among wrongdoers; • Second, that denying judicial relief to an admitted wrongdoer is Page | 206 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • an effective means of deterring illegality. Thus, to serve as both a sanction and as a deterrent, the law will not aid either party to an illegal agreement and will leave them where it finds them. Applicability • Applies only to contract with an illegal cause, subject matter, or purpose, whether the attendant facts constitute an offense or misdemeanor or whether the consideration involved is merely rendered illegal. • It does not apply to inexistent contracts, or to fictitious or simulated contracts. Rules If Both Parties Are In Pari Delicto • When 2 parties are equally at fault, the law leaves them as they are and denies recovery by either one of them. • No specific performance, or to recover the property agreed to be sold or delivered, or money agreed to be paid, or damages for its violate, an no affirmative relief of any kind will be given to one against the other. • Each must bearthe consequence of his own acts. • They will be left where they have placed themselves since they did not come into court with clean hands. • A good example of application of this principle is when foreigner acquires private lands in the Philippines, inviolates of the prohibition of the Constitution. • Aliens are disqualified from acquiring lands of the public domain, which includes private lands. Rationale: national patrimony. • Under Art 1412, foreigner cannot have the subject properties deed to him or allow him to recover the money he had spent for the purchase thereof. • In re petition for separation of property- elena buenaventure v. Helmut Muller and Beumer v. Amores Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 • Court denied the claim for reimbursement of the value of purchased parcels of land instituted by foreigner against his Filipina spouse. Rule If Only One Party Is At Fault • Guilty party • cannot recover what he has given by reason of the contract if contract has been executed, • cannot ask for the fulfillment of what has been promised to him if contract is merely executory • Innocent party • may demand return of the thing if contract was executed • May not be compelled to comply with his promise if contract is merely executory Article 1413. Interest paid in excess of the interest allowed by the usury laws may be recovered by the debtor, with interest thereon from the date of the payment. Article 1414. When money is paid or property delivered for an illegal purpose, the contract may be repudiated by one of the parties before the purpose has been accomplished, or before any damage has been caused to a third person. In such case, the courts may, if the public interest will thus be subserved, allow the party repudiating the contract to recover the money or property. Article 1415. Where one of the parties to an illegal contract is incapable of giving consent, the courts may, if the interest of justice so demands allow recovery of money or property delivered by the incapacitated person. Article 1416. When the agreement is not illegal per se but is merely prohibited, and the prohibition by the law is designed for the protection of the plaintiff, he may, if public policy is thereby enhanced, recover what he has paid or delivered. Article 1417. When the price of any article or commodity is determined by statute, or by Page | 207 authority of law, any person paying any amount in excess of the maximum price allowed may recover such excess. has a tendency to be injurious to the public or against the public good. Gonzalo vs Tarnate, Jr. Article 1418. When the law fixes, or authorizes the fixing of the maximum number of hours of labor, and a contract is entered into whereby a laborer undertakes to work longer than the maximum thus fixed, he may demand additional compensation for service rendered beyond the time limit. Article 1419. When the law sets, or authorizes the setting of a minimum wage for laborers, and a contract is agreed upon by which a laborer accepts a lower wage, he shall be entitled to recover the deficiency. 1. The innocent party (Arts. 1411- 1412) 2. The debtor who pays usurious interests (Art. 1413) 3. The party repudiating the void contract before the illegal purpose is accomplished or before damage is caused to a third person and if public interest is subserved by allowing recovery (Art. 1414) 4. The incapacitated party if the interest of justice so demands. (Art. 1415) 5. The party protection the prohibition by law is intended if the agreement is not illegal per se but merely prohibited and if public policy would be enhanced by permitting recovery (Art. 1416) 6. The party for whose benefit the law has been intended such as in price ceiling laws (Art. 1417) and labor laws (Arts 1418-1419) Violation of • Frenzel vs Catio • That principle of the law which holds that no subject or citizen can lawfully do that which The recovery on the basis of unjust enrichment cannot apply to a foreigner who acquired private lands in the Philippines in violation of the Constitutional prohibition. The prohibition on unjust enrichment does not apply if the action is proscribed by the Constitution. Pajuyo vs CA • The principle of pari delicto should not be applied to a case of ejectment between squatters. Reason: • Well- Public Policy The principle of pari delicto cannot be applied if it would contravene the public policy on prevention of unjust enrichment. Basis: Article 22 “Every person who through an act of performance by another, or any other means, acquires or comes into possession of something at the expense of the latter without just or legal ground, shall return the same to him.” • Exceptions to Principle of In Pari Delicto Recovery in Case of Established Public Policy • • To shut out relief to squatters on the ground of pari delicto would openly invite mayhem and lawlessness. A squatter would oust another squatter from possession of the lot that the latter had illegally occupied, embolded by the knowledge that the courts would leave them where they are. Nothing would hen stand in the way of the ousted squatter from re-claiming his prior possession at all cost. It would give squatter free rein to dispossess fellow squatters or violently retake possession of properties usurped from them. Courts could not leave squatters to their own devices in cases involving recovery possession. Page | 208 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 Recovery by Innocent Party • • • If only one of the parties is at fault, the innocent party may still demand for the return of what he has given if the contract has already been executed; but he may not be compelled to comply with his promise if the contract is merely executory. The law allows innocent parties to recover what they have given without any obligation to comply with their prestation but they are not entitled to an award of liquidated damages. No damages may be recovered on the basis of a void contract; being non-existent, the agreement produces no juridical tie between the parties involved. Recovery in Case of Usury • • A contract of loan with usurious interest consists of principal and accessory stipulations; the principal one is to pay the debt; the accessory stipulation is to pay the interest thereto. Ans said two stipulations are divisible in the sense that the former can still stand without the latter. Whether the illegal terms as to payment of interest likewise renders a nullity the legal terms as to payments of the principal debt. • In case of divisible contract, if the illegal terms can be separated from the legal ones, the latter may be enforced. Example: In simple loan with stipulation of usurious interest, the prestation of the debtor to pay the principal debt, which is the cause of the contract (Article 1350), is not illegal. Article 1413 states: “interest paid in excess of the interest allowed by the usury laws may be recovered by the debtor, with interest thereon from the date of the payment.” • It means the whole usurious interest. Illustration: In a loan of P1,000, with interest of 20% per annum P200 for one year, if the borrower pays said P200, the whole P200 is the usurious interest, not just that part thereof in excess of the interest allowed by law. • • • The whole stipulation as to interest is void, since payment of the said interest is the cause or object and said interest is illegal. The only change effected is not provide for the recovery of the interest paid in excess of that allowed by law, which the Usury Law already provided for, but to add that the same can be recovered “with interest thereon from the date of payment.” The whole interest paid may be recovered, with interest thereon from the date of payment. Party Repudiating Void Contract When money is paid or property delivered for an illegal purpose, recovery of what has been paid or delivered may be allowed if the following conditions are satisfied: 1. The party who seeks to recover has repudiated the contract. 2. The contract is repudiated before the purpose has been accomplished, or before any damage has been caused to a third person. 3. Public interest will be subserved by allowing recovery. Incapacitated Party • The illegality lies only as to the prestation to pay the stipulated interest; hence, being separable, the latter only should be deemed void, since it is the only one that is illegal. A party to an illegal contract may be allowed to recover what he had delivered if the following conditions are satisfied: Note: Page | 209 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021 1. Such party is incapable of giving consent to a contract. 2. If the interest of justice demands such recovery. Article 1421. The defense of illegality of contract is not available to third persons whose interests are not directly affected. Article 1422. A contract which is the direct result of a previous illegal contract, is also void and inexistent. • Contract not Illegal Per Se and Recovery will Enhance Public Policy Recovery for what has been paid or delivered pursuant to an inexistent contract is allowed only when the following requisites are met: • A void contract cannot give rise to a valid one. To the same effect is Article 1422, which declares that a contract which is the direct result of a previous illegal contract, is also void and inexistent. 1. The contract is not illegal per se but merely prohibited. 2. The prohibition is for the protection of the plaintiffs. 3. If public policy is enhanced thereby. Price Ceiling and Labor Laws • If the one recovering is the party for whose benefit the law has been intended, such as in price ceiling laws and labor laws, the law authorized recovery. 1. When the price of any article or commodity is determined by statute, or by authority of law, any person paying any amount in excess of the maximum price allowed may recover such excess. 2. When the law fixes, or authorizes the fixing of the maximum number of hours of labor, and a contract is entered into whereby a laborer undertakes to work longer than the maximum thus fixed, he may demand additional compensation for service rendered beyond the time limit. 3. When the laws sets, or authorizes the setting of a minimum wage for laborers, and a contract is agreed upon by which a laborer accepts a lower wage, he shall be entitled to recover the deficiency. Article 1420. In case of a divisible contract, if the illegal terms can be separated from the legal ones, the latter may be enforced. Page | 210 Reference: Rabuya 2019 Cruz, Mambuay, Makilan, Marasigan Suyat, Tang, Valenzuela – 1C – 2020-2021