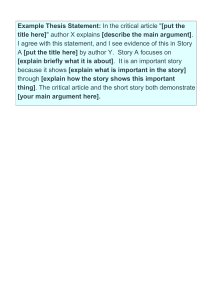

CRWT MIDTERMS WEEK 7: NATURE OF CRITICAL WRITING Reading and writing are two macroskills which are related to each other. Critical and active reading is not a process of passive consumption, but one of interaction and engagement between the reader and the text. Therefore, when reading critically and actively, it is important not only to take in the words on the page, but also to interpret and to reflect upon what is read through writing and discussing it with others. DESCRIPTIVE vs CRITICAL WRITING DESCRIPTIVE WRITING is fact-based. Examples include: • Facts and figures about a particular issue • Description of a background to a case study • Details of an organization • An account of how research was undertaken • A summary of a sequence of events • Descriptions of what happened in an experiment. REACTING vs RESPONDING TO A TEXT REACTING to a text - is often done on an emotional and largely subjective rather than on an intellectual and objective level. It is quick but shallow. BINARY READING - requires only “agree or disagree” answers - Does not allow understanding of complex arguments. RESPONDING to a text - requires a careful study of the ideas presented and arguments advanced in it. It is analytical and evaluative. It is productive and progressive. NUANCED READING - allows for deep and detailed understanding of complex texts - Establishes rhetorical engagement between the reader and the text CRITICAL WRITING is more complex, and involves more discussion, analysis and evaluation than does descriptive writing. Examples of critical writing activities include: •Engaging with evidence •Open minded and objective enquiry •Presenting reasons to dispute a particular finding •Providing an alternative approach •Recognizing the limitations of evidence: either your evidence or the evidence provided by others •Thinking around a specific problem REMEMBER: - Apply caution and humility when challenging established positions. Critical writers might tentatively suggest an independent point of view, using such phrases as ‘It could be argued that...’; or ‘An alternative viewpoint might suggest that...’. - Critical writing is no longer about observation and imagination. Rather, it strongly calls for observation and logic to raise solid arguments, supported by evidences that you will carefully elaborate in your text. A Lancaster University publication adds that “The aim of academic writing is not to present „the right answer,‟ but to discuss the controversies in an intelligent way.” WEEK 8: CRITICAL WRITING IN ACADEME Academic writing differs from other types of writing such as journalistic or creative writing. In most forms of academic writing a detached and objective approach is required. - It is far from a one-size-fits-all genre. - Applicable to the broad variety of academic disciplines and their unique approaches to conducting and documenting research efforts in the field, one might find it challenging to identify clearly what constitutes academic writing. Tips to help you reflect critical thinking in critical academic writing. Be sure to answer the right and relevant questions. Give enough contexts so that the reader can follow your ideas and understand your principles. Include references to the material you have read. Try to group different studies thematically or categorically and make links between ones that are related. Explain source material to your readers to show why it is valuable and relevant. Discuss the ideas that come from these source texts in your writing. Justify your judgments. Say why you think an idea is relevant, valid or interesting. Acknowledge the drawbacks or limitations of ideas, even the ones you disagree with. Avoid absolute statements. Use hedging language to make your statements more convincing. Do not be afraid to make intelligent suggestions, educational guesses or hypotheses. You are supposed to make judgments based on evidence, so your conclusions must be meaningful and completely objective. Note that conclusions are usually plural. A single conclusion—rare but possible—is usually straightforward and is worth discussing. Do not ignore arguments just because you disagree with them. Avoid praising authors just because they are famous in the field. Praise them for the substance of their work assessed with objectivity, not with subjectivity. Check that your argument flows logically. CRITICAL ACADEMIC WRITING According to the University of Birmingham publication, “A short guide to critical writing for Postgraduate Taught students,” “Critical writing is an involvement in an academic debate. It requires a refusal to accept the conclusions of other writers without evaluating the arguments and evidence they provide. ‟” In an academic writing assignment, you will start by asking a good question, then find and analyze answers to it, and choose your own best answer(s) to discuss in your paper. Your paper will share your thoughts and findings and justify your answer with logic and evidence. So, the goal of academic writing is not to show off everything that you know about your topic, but rather to show that you understand and can think critically about your topic. PRINCIPLES OF ACADEMIC WRITING CLEAR PURPOSE - The goal of your paper is to answer the question you posed as your topic. Your question gives you a purpose. - The most common purposes in academic writing are to persuade, analyze/synthesize, and inform. Persuasive Purpose - In persuasive academic writing, the purpose is to get your readers to adopt your answer to the question. - So, you will choose one answer to your question, support your answer using reason and evidence, and try to change the readers’ point of view about the topic. - Persuasive writing assignments include argumentative and position papers. Analytical Purpose - In analytical academic writing, the purpose is to explain and evaluate possible answers to your question, choosing the best answer(s) based on your own criteria. - Analytical assignments often investigate causes, examine effects, evaluate effectiveness, assess ways to solve problems, find the relationships between various ideas, or analyze other people’s arguments. Informative Purpose - In informative academic writing, the purpose is to explain possible answers to your question, giving the readers new information about your topic. - This differs from an analytical topic in that you do not push your viewpoint on the readers, but rather try to enlarge the readers’ view. AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT - As with all writing, academic writing is directed to a specific audience in mind. Unless your instructor says otherwise, consider your audience to be fellow students with the same level of knowledge as yourself. - You will have to engage them with your ideas and catch their interest with your writing style. Imagine that they are also skeptical, so that you must use the appropriate reasoning and evidence to convince them of your ideas. CLEAR POINT OF VIEW - Academic writing, even that with an informative purpose, is not just a list of facts or summaries of sources. - Although you will present other people’s ideas and research, the goal of your paper is to show what you think about these things. - Your paper will have and support your own original idea about the topic. This is called the thesis statement, and it is your answer to the question. SINGLE FOCUS - Every paragraph (even every sentence) in your paper will support your thesis statement. - There will be no unnecessary, irrelevant, unimportant, or contradictory information (Your paper will likely include contradictory or alternative points of view, but you will respond to and critique them to further strengthen your own point of view). LOGICAL ORGANIZATION Academic writing follows a standard organizational pattern. For academic essays and papers, there is an introduction, body, and conclusion. INTRODUCTION catches the readers’ attention, provides background information, and lets the reader know what to expect. It also has the thesis statement. BODY PARAGRAPHS support the thesis statement. Each body paragraph has one main point to support the thesis, which is named in a topic sentence. Each point is then supported in the paragraph with logical reasoning and evidence. Each sentence connects to the one before and after it. CONCLUSION summarizes the paper’s thesis and main points and shows the reader the significance of the paper’s findings. STRONG SUPPORT - Each body paragraph will have sufficient and relevant support for the topic sentence and thesis statement. - This support will consist of facts, examples, description, personal experience, and expert opinions and quotations. CLEAR & COMPLETE EXPLANATIONS - This is very important! As the writer, you need to do all the work for the reader. The reader should not have to think hard to understand your ideas, logic, or organization. EFFECTIVE USE OF RESEARCH - Your paper should refer to a variety of current, highquality, professional and academic sources. You will use your research to support your own ideas. CORRECT APA STYLE - All academic papers should follow the guidelines of the American Psychological Association. WRITING STYLE - Your writing should be clear, concise, and easy to read. It is also very important that there are no grammar, spelling, punctuation, or vocabulary mistakes in academic writing. Errors convey to the reader that you do not care. THE WRITING PROCESS PLAN • Always start by thinking about the purpose of the communication. The information and points that you want to present in your writing should target the specific audience that you try to inform or convince. CHOOSE A TOPIC • Think about things related to your interest. • Narrow your ideas from subjects to topics. • Write your topic as a question. BRAINSTORM • Write down all the possible answers to your question, and write down all the information, opinions, and questions you have about your topic. RESEARCH & FACT CHECK TO ENSURE DEPTH INFO • What you must remember is that “doing good research takes time.” Do not expect to do research once and find everything that you need for your paper. • The depth and amount of detail you include are also important. Sometimes, lots of detail is necessary, while in other cases the focus should be on getting to the point quickly; this decision depends on your reader. PIQUE THE READERS’ INTEREST • One way to do this is to show readers how the information will impact them: “Let them know up front why the topic you are addressing is of interest to them.” DISCOVER YOUR THESIS STATEMENT A good thesis statement usually includes: • Main idea of the paper. ONE idea. The entire paper is based on this statement. • Your opinion or point of view. The thesis statement is not a fact nor a question, but your view of the topic and what you want to say about it. • Purpose of the paper. From the thesis, it should be clear what the paper will do. • Answer to the research question. Ask yourself the question and then answer it with your thesis. Is it truly an answer? (if not, change the question or the answer!) • An element of surprise. This means that the thesis is interesting, engaging, and perhaps not so expected. • Clarity. It should be understandable after one reading and have no mistakes. OUTLINING • A basic outline is your first attempt to organize the ideas of your paper. It will help you focus your research and consider the order of your ideas. • You need to outline your goals and the points that you want to write about to achieve those goals. List down everything that you deem relevant and along the way, you might have to add or delete some points. REACH YOUR AUDIENCE • To effectively reach your audience, consider the terminology you use and the information you include. Using known terms and clearly explaining information allows the reader to better understand the document. WRITE, REVISE, EDIT, PROOFREAD • Finishing the last sentence is not the end of the writing process because professional writing is reader-, not writer-, centered. Be certain that your audience understands the topic. CONSTRUCTING A GOOD ACADEMIC ARGUMENT - A good academic argument makes an evidencebased claim designed to advance a specific field of study. - It also demonstrates an understanding of the foundational research for the claim and the implications of the results on the field. - Points of view can strengthen your argument, either by providing evidence to support your argument or by providing food for thought when constructing your argument to effectively debate counterclaims. A Belmont University resource titled, “Writing an Argument,” states: “The purpose of argument writing is to present a position and to have an audience adopt or at least seriously consider your argument.” Further, it notes that “Good argument writing is critical, assertion-with proof-writing. It should reflect a serious attempt on the writer’s part to have considered the issue from all angles.” The Simon Fraser University “Resources on argumentation in academic writing” claims that: “Argumentation is less about trying to change what readers believe, think, or do,‟ and more about convincing „yourself or others that specific facts are reliable or that certain views should be considered or at least tolerated‟”. Critical evaluation of source materials allows you “to evaluate the strength of the argument being made by the work”. The University of Toronto resource, “Critical Reading Towards Critical Writing” echoes this mindset, stating: “To read critically is to make judgments about how a text is argued. This is a highly reflective skill requiring you to “stand back” and gain some distance from the text you are reading.” For those new to critical evaluation of a source, however, you should ask “What aspects are important to consider when critically evaluating a source?” According to Sheldon Smith, founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com in an article on Critical Reading, “In addition to what a text says, the reader needs to consider how it says it, who is saying it, when it was said, where it was said (i.e. published), and why it was said (i.e. the writers purpose).” Why is it important to be able to critically evaluate source materials? “Building Good Arguments”, they describe six elements of a well-reasoned argument: claim, reason, qualifier, warrant, backing, and conditions of rebuttal. The University of Minnesota Center for Writing says, “When you understand how what you read is written, you can work to incorporate those techniques into your own writing”, while the Walden University Academic Skills Center offers that “You are not simply absorbing the information; instead, you are interpreting, categorizing, questioning, and weighing the value of that information” in support of critical reading processes. The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers that: RECEIVING CRITICISMS “...by considering what someone who disagrees with your position might have to say..., you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument.” CRITICALLY EVALUATING SOURCE MATERIALS According to the Cleveland State University Writing Center, “Critical reading means that a reader applies certain processes, models, questions, and theories that result in enhanced clarity and comprehension.” Many times, critically evaluating the work of others is much easier than receiving critical feedback on your own writing efforts. It is just harder to be at the receiving end. According to Eric Schmieder, “I think you have to face criticism with an open mind and a willingness to learn. Sometimes the comments are harsh, but mostly they are well-intentioned efforts to help you improve. Consider the source and select ones whose feedback you value when possible.” To better respond to critical feedback on your writing, Turn It In offers seven ways to improve writing by receiving feedback. 1. Feedback Connects to Your Goals Feedback lets you know how much development you have made towards your writing goals and what else you need to do to meet them. It also gives you a clearer picture of where you are in your timeline of progress. 2. Feedback Can Be More Important Than Your Score Scores and grades only measure performance -- they do not tell you how to get better. Read all the comments and use them to revise your work. A good score without feedback leaves you at a plateau while a bad score with feedback leaves you an opportunity to progress and improve without limits. 3. Feedback Helps You Ask the Right Questions You might not always understand the comments you get. You may even disagree with them, and sometimes you may have trouble understanding how to apply them. Ask your instructor for more clarification and advice. Teachers prefer assertive students that show interest for learning. 4. Feedback Lets You Determine What Is Most Important Focus on the comments that will make your ideas clearer and help readers understand, then work your way down. 5. Feedback Aids in Revision and Practice Use your comments to revise and practice your writing. You may also use your current feedback to reflect on the mistakes that you have committed in the past. 6. Feedback Helps You Take Ownership of Your Writing Find your voice as a writer and establish your own style and principles. 7. Feedback Gets You on the Same Page as Your Teacher Your teacher’s comments are there to help you, not criticize you. Your feedback is part of a conversation through which your teacher is trying to support you and your writing development. WEEK 9: WRITING IN THE WORKPLACE IMPORTANCE OF WRITING SKILLS IN BUSINESS AND WORKPLACE 1. Writing skills ensure effective business communication Business correspondence helps a company connect with partners and stakeholders. If a text is poorly written and structured, the message may be misinterpreted and may lead to loss of business transaction or even to permanent loss of partnership. 2. Writing skills make the difference between "good" and "bad" employees Crafting your own resume and cover letter may pose a real challenge, especially when you have to tailor fit them to the position and industry that you are trying to apply for. Furthermore, a document filled with grammatical errors will not impress anyone in the business organization, which you need to secure the job. Professionals are good at composing clear messages. Employers value such workers. That is the reason why companies invest so much in their recruitment and training processes. Practice writing as often as you can in order to stand out among your co-workers. Senior management is generally more favorable towards an employee who can create excellent documentation. 3. You demonstrate your intelligence with quality writing A few grammatical or punctuation errors may seem minor, but people do notice them even when they do not show any reaction and give you feedback. They tend to think that those who do not write well are less intelligent than those who do. Do not let anyone dismiss you because of your poor writing skills. A few minutes of proofreading can improve the way you are perceived, prompting everyone to take you more seriously. 4. Good writers are credible People with advanced writing skills are perceived as more reliable and trustworthy. Producing flawless documents will also make you look more credible than those who produce subpar quality. People, especially those from outside the business organization, will judge you the first time they see you. Unfortunately, on most occasions, customers and clients first see you through your writing, whether it is via an email, a sales letter or a phone call. Hence, it is crucial to establish a great first impression that might last a long time. 5. You can be more influential Good persuasion skills help you to influence others to achieve your goals. This is especially true for those who will delve deeper into the fields of marketing, sales, communications, public relations and law. Professors assign their students to write persuasive essays in order to prepare them for the job market by developing these significant skills. If you are creating taglines and calls-to-action for your organization, you need to know how to develop a copy that will encourage the reader to take action. If you are describing an innovative idea that can improve a process to your manager, you should sound convincing. 6. Business writing conveys courtesy Professionals take into consideration formatting and etiquette. They also pay attention to their personal tone, clarity, and logic. They avoid poor word choice and grammar. These things can come across as lazy or even rude. 7. Writing skills help to keep good records Information that is communicated orally is not kept for long. That is the reason why students take notes of lectures. As scholars use their notes to write essays, you can apply your records in your work. Keeping a record of your writing, especially when you belong to industries related to creativity and concepts, can also help you build a reliable portfolio that may be used for career advancement. 8. You boost your professional confidence When written communication leads a business to another successfully completed project, you become more confident and inspired, not to mention more eligible for promotion. Who does not like to advance in the career ladder? 9. You promote yourself and your career The better your writing skills are, the more responsibility you will be given. That is great for you and your future career success. 10. Business writing builds a solid web presence Business is all about presentation. Owners aim to set up an effective online presence, especially nowadays that the marketing game has turned digital. It helps potential customers discover the company and its products. Quality content is a decisive factor here. A person who can present business in the best light and convince people to buy products or services is an irreplaceable employee. You can even establish a lucrative career in marketing communications and digital marketing with this. WEEK 10: STRATEGIES IN CRITICAL WRITING Experienced writers showcase flexibility in achieving their objectives by constantly exploring and discovering styles, procedures, and ideas. They are not afraid to ask questions and question their own writing for a more balanced output. After all, writing is all about thinking. Only after the writer thoroughly examines the subject through writing and is satisfied with the ideas discovered, does he or she polish the writing for the reader. This is where the writer starts deciding on the style and organization to be used depending on the target readers and the nature of the text. This is where the writer also decides which critical strategies to use for writing the final draft. Critical thinking yields several strategies that you are likely to use in academic writing. Many of your writing assignments may reflect just one of the strategies or a combination of them. For the sake of clarity, these strategies have been arranged in the order of complexity of the critical thinking that they require. Keep in mind that these strategies often overlap with each other. You may use comparison and contrast when you are synthesizing information, but you may also synthesize the results of a causal analysis. You may also use several of these analytical strategies when you write an evaluation. ANALYSIS EVALUATION - the basis of many other strategies, is the process of breaking something into its parts and putting the parts back together so that you can better understand the whole. - is the most complex of all analytical strategies and uses many of the other analytical techniques. - When you seek to explain the causes and effects of a situation, event or action, you are trying to identify their origins and understand their results. You may discover a chain of events that explain the causes and effects. How you decide where the boundaries of causal analysis are depends on your thesis and your purpose for writing. SYNTHESIS - is a tad more complex than the analytical strategies that have just been discussed. - In synthesizing information, you must bring together all your opinions and researched evidence in support of your thesis. You integrate the relevant facts, statistics, expert opinions, and whatever can directly be observed with your own opinion and conclusions to persuade your audience that your thesis is correct. Indeed, you use synthesis in supporting a thesis and assembling a paper. HOW TO WRITE A SYNTHESIS • Identify the appropriate texts to use. You may find it helpful to use the notes and references in one appropriate source to find other relevant sources. • Read the sources carefully in relation to your purpose. Take notes or annotate your own copies to be able to retrieve relevant information easily. • Think about the connections among the various sources. Do any of the sources agree or disagree on any points? Does one source provide background for another? Does one source take up where other leaves of? Does one source provide an example of an idea discussed in another source? Do any common ideas or viewpoints run through all the sources? • Based on the pattern of connections you have seen among the various sources, develop an overall point or conclusion to serve as the organizing thesis of your synthesis. • Develop a plan for presenting the various parts of the information in a unified way. - In applying this strategy, you first establish the criteria you will use to evaluate your subject, apply them to the specific parts of the subject you are judging, and draw conclusions about whether your subject meets those criteria. - In the process of evaluating a subject, you will usually be called upon to render some analysis and synthesis and even use persuasive or argumentative techniques. establish the evaluation criteria select the characteristics you will apply those criteria to evaluate how well the selected characteristics meet the criteria present your results, along with examples, to support your premise PERSUASION - is aimed at changing the beliefs or opinions of the readers or at encouraging them to accept the credibility or possibility of your opinion or belief. - You do not have to convince them to embrace and adapt to your own opinions and beliefs offhand, although that is more preferential. Rather, you have to convince them to consider you by keeping an open mind. - At some level, all writing has a persuasive element. You may simply be persuading your reader to continue reading your writing or even to accept your credibility— that you know your subject area. In fiction writing, you persuade your readers to believe your plot and dialogues, enough for them to finish the story down to the last chapter. You can make your writing persuasive by responding to the needs and demands of your readers. When you keep them in mind, you can identify with their points of view and attitudes. Use your style and tone to show respect for your reader. Offer your reader arguments and evidence to support your opinion or belief. WEEK 11: ARGUMENTS IN CRITICAL WRITING What Makes GOOD ARGUMENT? ACADEMIC ARGUMENT A good argument should be convincing. You should find yourself believing the claim, or at least finding the conclusion reasonable. The term ‘argument’ is used in everyday language to describe a dispute or disagreement between two or more people. However, within written academic work, the presence of an argument does not always indicate a disagreement. An Argument can be used to: • Support something, we think has merit – a position, a point of view, a program, an object. • Persuade someone that something would be beneficial to do (or not to do) – a course of action. • Convince someone that something is true, likely to be true or probable – a fact, an outcome. • Show someone the problems or difficulties with something – a theory, an approach, a course of action. • Reason with someone to get them to change their mind or their practice. This entails several things: • acceptable or reasonable premises (likely to be true) • evidence or reasons that are relevant to the claim •reasons which provide sufficient grounds to lead us to accept the claim. These are called the acceptability, relevance and grounds of an argument. If an argument satisfies these three conditions, it is likely to be a good argument. How do I write an Argument? •Ensure you understand the question. What do you have to do? What issues do you need to cover? •Do your research. What do we know about this issue? What do the researchers say? What are the debates, the problems? •Go back to the question and consider your answer, given your research and what you have learnt. This will be your claim. Make it very clear what position or point of view you are taking. • How will the evidence from your research support your case? - Integrate supporting evidence by quoting and/or paraphrasing. - Acknowledge counter arguments/counter evidence. - Use linking words and discourse markers to draw connections between your argument and the evidence and/or counter evidence. •Argue for this position in an academic context. Consider your claim and supporting premises and draw out the implications: - Why am I saying this here? - What point am I trying to make? - What does this evidence show? •Make sure your essay has a clear, logical structure with relevant points which lead to the conclusion. It should be easy for your readers to follow where you are heading and why. Building Good Arguments In building good arguments, students and professionals usually follow two established methods that are effective both in academic and professional settings. You may choose whatever you deem is more effective depending on the type of issue that you raise. TOULMIN METHOD Philosopher Stephen Toulmin offers six elements of a well-reasoned argument and explains how they all work together. 1. Claim - is a debatable statement that requires proof. Fact Judgment or Evaluation Policy Keep in mind that a claim is only the starting point for a fully developed argument. 2. Reason - is a statement justifying the claim (e.g., a “because”-clause). A reason then invites evidence (sometimes called data) to support a claim and show its validity. 3. Qualifier - is a word or phrase (adjective or adverb) that limits the scope or “generalizability” of your claim. Without a qualifier, your claim may seem too broad or unrealistic for your readers. Using qualifiers appropriately also helps you to avoid binary or “either/or” thinking, which can invalidate an argument. Instead of using the following qualifiers: always never all none, no totally, completely, absolutely Try using the following qualifiers: sometimes, at times, occasionally, usually, frequently many, many a, some, more (or if applicable, a precise number or amount) a small number, a few, most (or if applicable, a precise number or amount) likely, possibly, probably 4. Warrant is an assumption or point of agreement shared by the arguer and the audience. In argument, we rely frequently on these fundamental shared assumptions. Warrants may remain unspoken (but understood) when a writer and reader can be expected to know or agree on them. This is normally the case for general knowledge and widely accepted facts. If readers do not share the same assumptions about the validity of the writer’s evidence, or if they do not recognize the assumption, they might not accept the evidence or claim. 5. Backing is additional information that justifies or enhances the credibility of your evidence. You need this to ensure that you audience will accept your evidences or claims. 6. Conditions of Rebuttal - are the potential objections to an argument. To deal with possible objections, imagine a skeptical yet reasonable reader poking holes in your claim and reasons or coming up with opposite, equally valid reasons