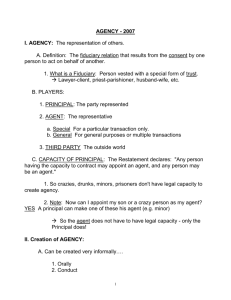

AUTHORITY OF THE AGENT Implied obligations between principal and agent If the agency arrangement is intentional, it may already be set out in a written contract what the agent can or cannot do, where and when it has to perform obligations, and what level of skill they need to use. If so, these are said to be express duties. Duties can however be implied into agency, and arise where there is no written agreement. Each country has differing approaches on this. English courts have been historically reluctant to impose terms into commercial contracts if they are otherwise fairly comprehensive as to express terms, but if the agency is not commercial, significant implied terms can be implied. Both a) whether or not an implied duty has arisen, or b) whether the implied duty has been breached can be open to interpretation and so it is usually safer to include these in a written agreement. If the dispute revolves around interpretation, it can be much more difficult to predict what a court would decide and they court retains a high level of autonomy. Duties of the agent to principal Some key duties the agent owes to the principal, implied by common law are: The agent has to keep the principal’s information confidential. This can be especially critical in manufacturing arrangements where the entire business’s value is grounded on a closely guarded process or recipe. An agent cannot delegate its own duties without the consent of the principal. An agent is often hired or instructed precisely because of their personal skill and knowledge. If the agent opts to outsource their duties deceptively, the actions of the other party will likely lie with the agent. If individual skill is not at all material, then subcontracting may be possible. The agent has to properly account for property and monies received, for the principal. To do not do so could amount to theft and conversion, as well as being a breach of duty. The agent has to follow the reasonable instructions of the principal. If they fail to do so, the liability for any wrongdoing might rest with the agent. If the agent’s fees are dependent on specific instructions, and they fail to do them, the agent might not be entitled to any money. The agent has to do so with reasonable care and skill, if they don’t, they may be partly accountable. The agent has to stick within the guidelines it has been given, provided these are reasonable. The guidelines might be very narrow, and if the agent purposefully ventures outside of these, it could be argued they didn’t have authority and liability ought to rest with them. The agent in a common law situation owes a duty of good faith to the principal, and must not make undue profit from abuse of the agent’s position, they cannot pursue conflicting interests, and has to disclose if a third-party benefits. If the agent doesn’t do so, this could be said to be a breach of implied duties. There is on-going uncertainty whether good faith also applies to commercial agency and case law on this is mixed, but only likely applies in very limited circumstances. The agent has to disclose material facts to the principal. It cannot present halftruths. If the agent agrees to do something, it has to do so within a reasonable time frame. What is reasonable may depend on what is being contracted for. If it is to sell perishable goods, the need to act quickly may be enhanced. An agent may have a duty not to act in a particular geographic area if it can be implied this was the nature of their instructions, but may only be enforceable if implied if it protects a legitimate business interest and goes no further than is reasonable. These factors will turn on the facts. Duties of the principal to agent If a principal has implied it will pay the agent for services provided, there can be an implied duty that it has to be bound to that agreement. If payment to the agent is conditional on something happening which doesn’t, the obligation may fall away. If payment is conditional on introduction of a customer and the principal refuses to proceed for no good reason and refuses to pay the agent, the principal may be held to be in breach. A principal has to pay the expenses of agents which they incur in discharging their obligations, unless otherwise agreed. Unless otherwise agreed, the principal may have to indemnify the agent for any losses it incurs whilst properly carrying out the principal’s instructions. If the arrangement is covered by commercial agency regulations, the principal may be found to act in good faith towards the agent, but there is no general requirement in common law agency. If the principal restricts the agent’s authority and the third party knows about that restriction and the agent causes a dispute, then the principal may not be held liable. Vicarious liability of principal The term vicarious liability is often used in legal circles but more simply means the principle where one person can be held liable by the actions of another. It comes into play often in agency situations. Liability of agent If an agent is negligent in carrying out their duties, they may be liable to either the principal or third party directly. If the agent is deceptive or acts fraudulently, agents may be held liable in civil and criminal law. An agent may become liable personally for a dispute when acting as an agent if they do not make their agency status sufficiently clear; in which case the agent may be seen to have contracted personally. Remedies will most commonly be damages or compensation for loss suffered. The court could order that the contract is terminated or that it continues potentially. The court could order an account of profit, if the agent makes unauthorized money at the principal’s expense. There could be added compensation for breach of implied duties and terms. An agent might obtain a right over the principal’s property until such time as the principal makes full payment. The contract might be rescinded, which is to say to put the parties back in the position as if the contract had never gone ahead. If money is thought to be inadequate, then potentially the court could order the agent to complete whatever it is they haven’t done. Query then whether they would do it well! Termination of agency A common dispute which habitually arises is whether an agency agreement can be terminated part way through and what is the outcome. For commercial agency, governed by Regulations, if it is terminated, the agent may be entitled to compensation as a matter of course, and the dispute can extend to what value of compensation is just. There is a minimum amount of notice required. An agency agreement may be terminated automatically in law, if the task has been completed, if the contract has been frustrated, if death, insolvency or insanity applies. There is no general outcome of termination in common law, and each case turns on its facts as to what is agreed or can be implied. The agency relationship is created either by mutual consent or by operation of law; or by ratification. A consensual relationship created by contract or by law where one party, the principal, grants authority for another party, the agent, to act on behalf of and under the control of the principal to deal with a third party. An agency relationship is fiduciary in nature, and the actions and words of an agent exchanged with a third party bind the principal. An agreement creating an agency relationship may be express or implied, and both the agent and principal may be either an individual or an entity, such as a corporation or partnership. Under the law of agency, if a person is injured in a traffic accident with a delivery truck, the truck driver's employer may be liable to the injured person even if the employer was not directly responsible for the accident. That is because the employer and the driver are in a relationship known as principalagent, in which the driver, as the agent, is authorized to act on behalf of the employer, who is the principal. The law of agency allows one person to employ another to do her or his work, sell her or his goods, and acquire property on her or his behalf as if the employer were present and acting in person. The principal may authorize the agent to perform a variety of tasks or may restrict the agent to specific functions, but regardless of the amount, or scope, of authority given to the agent, the agent represents the principal and is subject to the principal's control. More important, the principal is liable for the consequences of acts that the agent has been directed to perform. A voluntary, good faith relationship of trust, known as a fiduciary relationship, exists between a principal and an agent for the benefit of the principal. This relationship requires the agent to exercise a duty of loyalty to the principal and to use reasonable care to serve and protect the interests of the principal. An agent who acts in his or her own interest violates the fiduciary duty and will be financially liable to the principal for any losses the principal incurs because of that breach of the fiduciary duty. For example, an agent who accepts a bribe to purchase only the goods from a particular seller breaches his fiduciary duty by taking the money, since it is the agent's duty to work only for the best interests of the principal. An agency relationship is created by the consent of both the agent and the principal; no one can unwittingly become an agent for another. Although a principal-agent relationship can be created by a contract between the parties, a contract is not necessary if it is clear that the parties intend to act as principal and agent. The intent of the parties can be expressed by their words or implied by their conduct. Perhaps the most important element of a principal-agent relationship is the concept of control: the agent agrees to act under the control or direction of the principal. The extent of the principal's control over the agent distinguishes an agent from an independent contractor, over whom control and supervision by the principal may be relatively remote. An independent contractor is subject to the control of an employer only to the extent that she or he must produce the final work product that she or he has agreed to provide. Independent contractors have the freedom to use whatever means they choose to achieve that final product. When the employer provides more specific directions, or exerts more control, as to the means and methods of doing the job—by providing specific instructions as to how goods are to be sold or marketed, for example—then an agency relationship may exist. The agent's authority may be actual or apparent. If the principal intentionally confers express and implied powers to the agent to act for him or her, the agent possesses actual authority. When the agent exercises actual authority, it is as if the principal is acting, and the principal is bound by the agent's acts and is liable for them. For example, if an owner of an apartment building names a person as agent to lease apartments and collect rents, those functions are express powers, since they are specifically stated. To perform these functions, the agent must also be able to issue receipts for rent collected and to show apartments to prospective tenants. These powers, since they are a necessary part of the express duties of the agent, are implied powers. When the agent performs any or all of these duties, whether express or implied, it is as if the owner has done so. A more complicated situation arises when the agent possesses apparent authority. In this case, the principal, either knowingly or even mistakenly, permits the agent or others to assume that the agent possesses authority to carry out certain actions when such authority does not, in fact, exist. If other persons believe in good faith that such authority exists, the principal remains liable for the agent's actions and cannot rely on the defense that no actual authority was granted. For instance, suppose the owner of a building offers it for sale and tells prospective buyers to talk to the rental agent. If a buyer enters into a purchase agreement with the agent, the owner may be liable for breaching that contract if she later agrees to sell the building to someone else. The first purchaser relied on the apparent authority of the agent and will not be penalized even if the owner maintains that no authority was ever given to the agent to enter into the contract. The owner remains responsible for acts done by an agent who was exercising apparent authority. The scope of an agent's authority, whether apparent or actual, is considered in determining an agent's liability for her or his actions. An agent is not personally liable to a third party for a contract the agent has entered into as a representative of the principal so long as the agent acted within the scope of her or his authority and signed the contract as agent for the principal. If the agent exceeded her or his authority by entering into the contract, however, the agent is financially responsible to the principal for violating her or his fiduciary duty. In addition, the agent may also be sued by the other party to the contract for fraud. The principal is generally not bound if the agent was not actually or apparently authorized to enter into the contract. With respect to liability in tort (i.e., liability for a civil wrong, such as driving a car in a negligent manner and causing an accident), the principal is responsible for an act committed by an agent while acting within his or her authority during the course of the agent's employment. This legal rule is based on respondeat superior, which is Latin for "let the master answer." The doctrine of respondeat superior, first developed in England in the late 1600s and adopted in the United States during the 1840s, was founded on the theory that a master must respond to third persons for losses negligently caused by the master's servants. In more modern terms, the employer is said to be vicariously liable for injuries caused by the actions of an employee or agent; in other words, liability for an employee's actions is imputed to the employer. The agent can also be liable to the injured party, but because the principal may be better able financially to pay any judgment rendered against him or her (according to the "deep-pocket" theory), the principal is almost always sued in addition to the agent. A principal may also be liable for an agent's criminal acts if the principal either authorized or consented to those acts; if the principal directed the commission of a crime, she or he can be prosecuted as an accessory to the crime. Some state laws provide that a corporation may be held criminally liable for the acts of its agents or officers committed in the transaction of corporate business, since by law a corporation can only act through its officers. An agent's authority can be terminated only in accordance with the agency contract that first created the principal-agent relationship. A principal can revoke an agent's authority at any time but may be liable for damages if the termination violates the contract. Other events—such as the death, insanity, or bankruptcy of the principal—end the principal-agent relationship by operation of law. (Operation of law refers to rights granted or taken away without the party's action or cooperation, but instead by the application of law to a specific set of facts.) The rule that death or insanity terminates an agent's authority is based on the policy that the principal's estate should be protected from potential fraudulent activity on the part of the agent. Some states have modified these common-law rules, allowing some acts of the agent to be binding upon other parties who were not aware of the termination. The law of agency is the law of delegation—i.e., the legal principles that govern the ability of one person (the principal) to have another person (the agent) act on his behalf. Basic agency relationships underlie virtually all commercial dealings in the modern world. For example, the relationship between a sole proprietor and his employees is governed by the law of agency, as is the relationship between a corporation and its officers. Technically, the agency relationship is not a form of business organization in and of itself; instead, agency is the mechanism by which business organizations function. To take an obvious example, a corporation—an artificial legal construct that has no physical being of its own—can act only through agents for everything it does. Regardless of whether the corporation is writing a check, selling a product, or entering into a multi-billion dollar merger, the law of agency is involved. An agent’s authority may be expressly given, impliedly given, and ostensible or apparent on the basic of the principle conducts. Actual authority can either be vested as express authority or implied authority. Express authority: This type of authority is created by words, either written or oral. It often derives from a contract between the principal and agent, although an agent may act gratuitously. No particular form is required unless the agent is appointed to execute a deed, in which case he must be given authority in a deed, called a power of attorney. Implied authority: The agent's implied authority permits him to perform all subordinate or incidental acts necessary to exercise his express authority. Implied authority cannot contradict express actual authority. Indeed implied authority is a way of filling in the gaps in the agency agreement. Implied authority may arise in the following circumstances: (a) Usual authority: This is a more specific form of implied authority which relates to agents of certain type acting in the "usual” way of such agents. The test is what authority would the reasonable appointed person in the agent’s position believe they possessed? It will be implied that someone appointed as a managing director of a company has the authority that managing directors possess. Watteau V. Fenwick (1893). The defendant had employed H. as manager of a hotel. H.’s name alone appeared over the bar as licensee. The defendant limited H.'s actual authority by forbidding him to buy cigars.’ However, the agent did order cigars from W. who knew nothing of the 3 existence of the prohibition. The court held that such purchases were within the usual authority of a hotel manager and F was bound to pay for the cigars. (b) Customary authority: Here, an agent’s implied authority drives from a locality, market or business usage. To imply a custom, it must be uniform, certain, notorious (that is, generally known), recognized as binding and reasonable. Customary authority will not be recognized where it contradicts either the express agreement between the agent and the principal or the normal duties owed by the agent to the principal. (c) Apparent or ostensible authority: An ‘apparent’ or ‘ostensible’ authority refers to the authority of an agent which one would accept an agent of that type to possess. If a third party has no notice that the authority of a particular agent is limited and is thus less than that normally enjoyed by such an agent, he can assume that the agent has such authority, and contract made by the agent within the boundaries of the agent’s ostensible or apparent authority will be binding on the principal. If the agent has exceeded the actual authority with which he has been invested but has bound his principal because the contract was within his ostensible authority, he will be liable to principal for any losses; for want of authority. See the case of Watteau v Fenwic, 1893. In Freeman and Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties Ltd (1964). In this case, the Articles of the defendant company created the office of Managing Director. However, at the material time none had been appointed. One director with knowledge of the others purported to Act as managing director. He engaged the Plaintiff firm to work for the company. The firm was not paid for services rendered to the company. In an action to enforce the contract, the company disclaimed liability on the ground that the director was not its Managing Director and hence had no authority to contract on its behalf in the said contract It was held that since the company had held out this director as its managing director the plaintiff was entitled to assume that he was its managing director. The company was estopped from denying its representations. Apparent authority may arise where there is or was an agency relationship in existence, but unknown to the third party, the actual authority has been limited or terminated. Apparent authority clearly operates to protect third parties and may arise even where there has been an agency relationship created between principal and agent. Apparent or ostensible authority is based on estoppel. The requirements for estoppel to arise are: 1. A representation by words or conduct that the agent” has authority. 2. The representation must be made by the principal to the third party. 3. The third party must have relied on the misrepresentation. This is shown by the third party entering into the contract. Once these conditions have been satisfied the principal will be prevented or estopped from denying the agency. Normally the principal’s representation precedes the contract’ but he may be bound by his behavior subsequent to the contract.