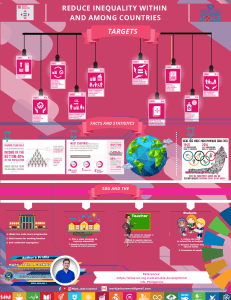

lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Geography 3- Urban Geography Module Social Issues and Professional Practice (Lyceum of the Philippines University) Scan to open on Studocu Studocu is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Geography 3 - Urban Geography Student’s Name: Degree Program: Section: Mobile Number: Professor Name: Email Address: YOUR GOALS Urban Geography is a branch of Human Geography that deals with various aspects of cities from ancient to modern times. Through this module, you will have a better appreciation of urban systems with reference to their geographical environment. It will give you insights on urban development with population growth, and the challenges that Asian cities are currently facing. Also, you will have a better understanding about the urban development in the Philippines as well as its challenges and opportunities, and how we can unlock the potential of creating more globalized cities in the country. At the end of this learning module, you are expected to demonstrate the following competencies: 1. Understand the basic information about urbanization and its connection to geographical set up of both ancient and modern-day cities around the world; 2. Analyze the impact of urban development in Asian cities and its underlying problems; and 3. Create a critical analysis that will explain the key areas related to continuous urban development in the country. YOUR EXPERIENCE Be guided by the following schedule that you can follow in order to manage your learning experience well: WEEK TASK OUTPUT 1 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 1 2 1 Create an infographic on the impact of urban development in Asian cities and its underlying problems. 3 4 2 Critical analysis about the continuous urban development in the country. 5 6 Essay on how Urban Geography became an important discipline to the economic, political and social aspects of our cities and how a city became a place of people with a similar way of cultural preferences, political views, and lifestyle. PROJECT There are required reading resources for this module. You are allowed to look for other related resources if you have the means to do so. Note that our school library has online resources that you can access. TASK 1: Read the materials for this task and write an essay pertaining to Urban Geography. TASK INFORMATION: Please take note of the following in formulating your answer. 1. Read thoroughly the materials for this task. 2. Construct an essay on how Urban Geography became an important discipline to the economic, political and social aspects of our cities and how a city became a place of people with a similar way of cultural preferences, political views, and lifestyle. 3. Your essay should be a minimum of 300 and a maximum of 500 words. The total number of words should be written at the last page of your essay. WRITING CONDITION: Take note of the following in crafting your essay. 1. Use the Answer sheet in writing your essay. 2 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 2. For computer-generated output, use the format (a) short bond paper, (b) font style is Century Gothic, (c) font size is 12, (d) double spacing, and (e) justified. 3. The file must be submitted with the filename SURNAME_FIRSTNAME_SUBJEC T_DATE SUBMITTED. RUBRIC OF ASSESSMENT: Take time to review the rubric of evaluation which informs you of how your Task 1 would be graded. SKILLS Exemplary (5) Proficient (4) Satisfactory (3) Outcome mastery Demonstrates Demonstrates a conscious and thoughtful thorough awareness of the understanding of knowledge and the knowledge and skills acquired for this domain skills acquired for this domain Depth of reflection Using student Using student Using student learning objectives learning learning objectives from course syllabi, objectives from from course syllabi, the student course syllabi, the student addresses what the student addresses either they learned, how addresses what what they learned they learned it, and they learned and or how they learned what is next with how they learned it for this domain, regard to learning, it, for this domain, and does not address plans for for this domain but does not address plans for future learning future learning Developing (2) Beginning ( 1 or 0) Demonstrates a Demonstrates a Demonstrates little or basic awareness of limited awareness no awareness of the some of the of one or two of knowledge and skills knowledge and skills the knowledge acquired for this acquired for this and skills domain domain over acquired for this domain The written information either what they learned, how they learned it, and/or what is next, for this domain, but does not tie the learning to objectives from course syllabi The written information provided does not reference student learning objectives from course syllabi, and does not address what they learned, how they learned it, or what is next, for this domain Substantiatio Artifacts provide n of claims specific examples to support claims and interpretations Artifacts provide relevant examples to support claims and interpretations Artifacts support most of the claims and some interpretations Artifacts provide Artifacts do not vague support to support the claims the claims and and interpretations interpretations Writing Student conventions demonstrates use of sophisticated language with essentially no spelling or grammatical errors Student demonstrates use of sophisticated language with almost no spelling or grammatical errors Student demonstrates use of clear and interpretable language with occasional spelling and grammatical errors Student demonstrates frequent errors and use of unclear or incomplete sentences so that comprehension is difficult Student demonstrates multiple errors so that comprehension is almost 3 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 YOUR POINTS AND NOTES (to be accomplished by the teacher) ANSWER SHEET: Place the content of your answers to the activity here. 4 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 5 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 6 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 READING MATERIAL NO. 1 An Overview of Urban Geography by Amanda Briney https://www.thoughtco.com/overview-of-urban-geography-1435803 Urban Geography Urban geography is a branch of human geography concerned with various aspects of cities. An urban geographer's main role is to emphasize location and space and study the spatial processes that create patterns observed in urban areas. To do this, they study the site, evolution and growth, and classification of villages, towns, and cities as well as their location and importance in relation to different regions and cities. Economic, political and social aspects within cities are also important in urban geography. In order to fully understand each of these aspects of a city, urban geography represents a combination of many other fields within geography. Physical geography, for example, is important in understanding why a city is located in a specific area as site and environmental conditions play a large role in whether or not a city develops. Cultural geography can aid in understanding various conditions related to an area's people, while economic geography aids in understanding the types of economic activities and jobs available in an area. Fields outside of geography such as resource management, anthropology, and urban sociology are also important. Definition of a City An essential component within urban geography is defining what a city or urban area actually is. Although a difficult task, urban geographers generally define the city as a concentration of people with a similar way of life-based on job type, cultural preferences, political views, and lifestyle. Specialized land uses, a variety of different institutions, and use of resources also help in distinguishing one city from another. In addition, urban geographers also work to differentiate areas of different sizes. Because it is hard to find sharp distinctions between areas of different sizes, urban geographers often use the rural-urban continuum to guide their understanding and help classify areas. It takes into account hamlets and villages which are generally considered rural and consist of small, dispersed populations, as well as cities and metropolitan areas considered urban with concentrated, dense populations. History of Urban Geography The earliest studies of urban geography in the United States focused on site and situation. This developed out of the man-land tradition of geography which focused on the impact of nature on humans and vice versa. In the 1920s, Carl Sauer became influential in urban geography as he motivated geographers to study a city's population and economic aspects with regard to its 7 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 physical location. In addition, central place theory and regional studies focused on the hinterland (the rural outlying are supporting a city with agricultural products and raw materials) and trade areas were also important to early urban geography. Throughout the 1950s and 1970s, geography itself became focused on spatial analysis, quantitative measurements and the use of the scientific method. At the same time, urban geographers began quantitative information like census data to compare different urban areas. Using this data allowed them to do comparative studies of different cities and develop computer-based analysis out of those studies. By the 1970s, urban studies were the leading form of geographic research. Shortly thereafter, behavioral studies began to grow within geography and in urban geography. Proponents of behavioral studies believed that location and spatial characteristics could not be held solely responsible for changes in a city. Instead, changes in a city arise from decisions made by individuals and organizations within the city. By the 1980s, urban geographers became largely concerned with structural aspects of the city related to underlying social, political and economic structures. For example, urban geographers at this time studied how capital investment could foster urban change in various cities. Throughout the late 1980s until today, urban geographers have begun to differentiate themselves from one another, therefore allowing the field to be filled with a number of different viewpoints and focuses. For example, a city's site and situation is still regarded as important to its growth, as is its history and relationship with its physical environment and natural resources. People's interactions with each other and political and economic factors are still studied as agents of urban change as well. Themes of Urban Geography Although urban geography has several different focuses and viewpoints, there are two major themes that dominate its study today. The first of these is the study of problems relating to the spatial distribution of cities and the patterns of movement and links that connect them across space. This approach focuses on the city system. The second theme in urban geography today is the study of patterns of distribution and interaction of people and businesses within cities. This theme mainly looks at a city's inner structure and therefore focuses on the city as a system. In order to follow these themes and study cities, urban geographers often break down their research into different levels of analysis. In focusing on the city system, urban geographers must look at the city on the neighborhood and citywide level, as well as how it relates to other cities on a regional, national and global level. To study the city as a system and its inner structure as in the second approach, urban geographers are mainly concerned with the neighborhood and city level. 8 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Jobs in Urban Geography Since urban geography is a varied branch of geography that requires a wealth of outside knowledge and expertise on the city, it forms the theoretical basis for a growing number of jobs. According to the Association of American Geographers, a background in urban geography can prepare one for a career in such fields as urban and transportation planning, site selection in business development and real estate development. READING MATERIAL NO. 2 Urban Morphology by K.D. Lilley https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/urban-morphology A Historical Geography of Urban Morphology Urban morphology has formed a part of Anglophone human geography since the early 1900s. The aim here is to summarize its development since then, and to identify particular ‘schools’ or traditions of urban morphology that emerged over this time. These ‘schools’ are an important dimension of morphological study internationally and reflect different strands of urban morphology as well as the influence of key thinkers at particular times. The most thorough surveys of these schools and their development are those by Whitehand. He divides urban morphology internationally into four main traditions, comprising ‘morphogenetic geographers’, ‘Conzenian geographers’, ‘other English-speaking geographers’, and ‘urban designers’. Since 1992, and thanks to the work of the International Seminar on Urban Form (ISUF), greater recognition has emerged of the diverse research traditions in urban morphology, especially those beyond the Anglophone world, summaries of which appear in the journal Urban Morphology, itself a sign of greater international dialog among urban morphologists of different traditions. As far as Anglophone urban morphology is concerned, its early influences came from continental Europe, Germany, and Italy in particular, during the middle decades of the twentieth century. The more dominant influence on those Anglophone urban morphologists who were geographers (rather than architects) was Germanic (rather than Italian), and derives from a strong tradition of settlement study and landscape morphology in central European geography, beginning with the work of Schlüter in the 1890s at the University of Hälle. This earliest work of German-speaking urban morphologists was characterized by a concern for creating typologies of historic urban forms, especially medieval towns and cities of continental Europe. For instance, a study of West German towns by Klaiber identified six plan types, while Geisler attempted to classify all German town plans according to their street systems in his book, Die Deutsche Stadt. By the 1940s, this ‘morphographic’, classificatory approach was giving way to 9 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 a ‘morphogenetic’ approach based upon principles of plan analysis in which the period compositeness of town plans was recognized and put to use in mapping out not typologies but histories of urban form. This had begun in the inter-war period with studies by Dörries, Bobek, and Rörig, and developed through a series of German historic town atlases that used large-scale town plans and also identified phases of historical urban development. It was this work by German-speaking urban morphologists that gradually became known by English-speaking geographers in the UK and USA. R. E. Dickinson had introduced German urban morphology to a geography audience in Britain in the 1930s, and also undertaken a typological study of town plans in eastern England very much like those of Klaiber and Geisler. In his West European City he also referred to the then more recent (and sophisticated) work of Bobek and Rörig. But Dickinson’s influence on Anglophone geographers was overtaken in the early 1960s by a German émigré geographer, M. R. G. Conzen, who used his grounding in German geography to develop an approach to urban morphology that has become known as the ‘Conzenian tradition’. In the US, it was the work of Leighly in the 1920s and 1930s that brought urban morphology into cultural geography, in particular, the Berkeley School, but the focus there was rather more on rural settlement than urban, and subsequently it was Conzenian urban morphology again that came to influence North American historical geographers’ work on built environments and urban landscapes. The ‘Conzenian geographers’, whose intellectual origins stem back to the ‘morphogenetic geographers’ of continental Europe, share a common belief that urban landscapes are dynamic yet at the same time conservative. This principle guides their thinking on the methods as well as applications of urban morphology. It concerns the historicity of the urban landscape, and the values attached to this. Conzen initially dealt with problems of method, of how to interpret town plans ‘morphogenetically’, and of how to disaggregate the morphological complexity of urban landscapes both in terms of their plan form and built fabric. He devised an approach, ‘town plan analysis’ to identify ‘plan elements’ (streets, plots, and buildings) that together constituted a town’s plan, and used this to define areas of morphological homogeneity, which he called ‘plan units’, each indicating a phase of urban morphogenesis as he saw it. Conzen conceptualized formation and redevelopment processes through his close analysis of streets, plots, and buildings, and paid particular attention to cyclical changes in form, for example, the formation of ‘fringe belts’ and the internal transformation of building lots (‘the burgage cycle’). These were discussed in his monograph on Alnwick, a small historic market town in northeast England. In this study he also paid attention to what else gave a townscape its character, not only its ‘town plan’ but also local ‘building fabric’ and ‘land utilization’. With building fabric, he sought to focus on architectural style and building materials and façade features, mapping building types in detail, and likewise with types of land utilization. Such detailed study required 10 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 fieldwork and not only borrowed on Conzen’s training as a geographer in Berlin between the wars but also his early profession as a town planner. The ways that these three ‘form complexes’ – town plan, building fabric, and land utilization – all combined gave rise, he suggested, to the genius loci, or spirit of place, achieved through long-term historical and morphological development and redevelopment processes. Conzen’s methodological and conceptual ideas, as well as his thinking on historical townscapes, has formed a critical school of thought in urban morphology that touches not only geography but also history, archaeology, architecture, and planning. In UK geography in particular, Conzen’s work was further developed in the 1970s and 1980s, primarily at the University of Birmingham under the auspices of the Urban Morphology Research Group (UMRG) set up by J. W. R. Whitehand. This fostered the Conzenian tradition and helped to disseminate Conzenian ideas across Britain, as well as Ireland. Two areas in particular were developed, one historical in focus concerning the use of ‘town plan analysis’ to reconstruct the early histories of European towns and cities, and the other more contemporary in focus concerning the role of agents and agency in urban redevelopment and development control. Through this activity, the ‘Conzenian school’ has gained identity and international recognition, with new links fostered between the UK and urban morphologists working in Spain and Poland. It has also revealed the presence of cognate schools of urban morphology, notably the ‘Italian school’ that had emerged in the 1950s and 1960s at the same time that Conzen was writing, through the work of Muratori and Caniggia. In the US too, the Conzenian tradition was fostered by an out-migration of UK geographers, including M. P. Conzen and Deryck Holdsworth. But neither in the UK nor the USA has urban morphology gained ascendancy in human geography as a whole. It remains a fairly peripheral part of the discipline. Indeed, by the 1990s, some UK geographers were beginning to suggest that urban morphologists’ view of ‘landscape’ was too narrow, too empirical, particularly in the light of a more theorized approach to landscape that had begun to root in Anglophone historical and cultural geography which was more concerned with iconography than morphology. With the foundation of ISUF, in 1994, and the publication of its journal Urban Morphology (since 1997), the various ‘schools’ of urban morphology present both within and between academic disciplines and national intellectual traditions have begun to cross-fertilize, making it perhaps now more difficult than 20 years ago to map out a genealogy of urban morphology as Whitehand did in the 1980s. The subject continues to attract comment, as it always has done, not just by geographers but also by others interested in understanding built forms and managing urban landscapes. 11 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 READING MATERIAL NO. 3 Urbanization and the Development of Cities https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-sociology/chapter/urbanization-an dth e-development-of-cities/ The Earliest Cities Early cities arose in a number of regions, and are thought to have developed for reasons of agricultural productivity and economic scale. Early cities developed in a number of regions, from Mesopotamia to Asia to the Americas. The very first cities were founded in Mesopotamia after the Neolithic Revolution, around 7500 BCE. Mesopotamian cities included Eridu, Uruk, and Ur. Early cities also arose in the Indus Valley and ancient China. Among the early Old World cities, one of the largest was Mohenjodaro, located in the Indus Valley (present-day Pakistan); it existed from about 2600 BCE, and had a population of 50,000 or more. In the ancient Americas, the earliest cities were built in the Andes and Mesoamerica, and flourished between the 30th century BCE and the 18th century BCE. Ancient cities were notable for their geographical diversity, as well as their diversity in form and function. Theories that attempt to explain ancient urbanism by a single factor, such as economic benefit, fail to capture the range of variation documented by archaeologists. Excavations at early urban sites show that some cities were sparsely populated political capitals, others were trade centers, and still other cities had a primarily religious focus. Some cities had large dense populations, whereas others carried out urban activities in the realms of politics or religion without having large associated populations. Some ancient cities grew to be powerful capital cities and centers of commerce and industry, situated at the centers of growing ancient empires. Examples include Alexandria and Antioch of the Hellenistic civilization, Carthage, and ancient Rome and its eastern successor, Constantinople (later Istanbul). The Formation of Cities Why did cities form in the first place? There is insufficient evidence to assert what conditions gave rise to the first cities, but some theorists have speculated on what they consider pre-conditions and basic mechanisms that could explain the rise of cities. Agriculture is believed to be a pre-requisite for cities, which help preserve surplus production and create economies of scale. The conventional view holds that cities first formed after the Neolithic Revolution, with the spread of agriculture. The advent of farming encouraged 12 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 hunter-gatherers to abandon nomadic lifestyles and settle near others who lived by agricultural production. Agriculture yielded more food, which made denser human populations possible, thereby supporting city development. Farming led to dense, settled populations, and food surpluses that required storage and could facilitate trade. These conditions seem to be important prerequisites for city life. Many theorists hypothesize that agriculture preceded the development of cities and led to their growth. A good environment and strong social organization are two necessities for the formation of a successful city. A good environment includes clean water and a favorable climate for growing crops and agriculture. A strong sense of social organization helps a newly formed city work together in times of need, and it allows people to develop various functions to assist in the future development of the city (for example, farmer or merchant). Without these two common features, as well as advanced agricultural technology, a newly formed city is not likely to succeed. Cities may have held other advantages, too. For example, cities reduced transport costs for goods, people, and ideas by bringing them all together in one spot. By reducing these transaction costs, cities contributed to worker productivity. Finally, cities likely performed the essential function of providing protection for people and the valuable things they were beginning to accumulate. Some theorists hypothesize that people may have come together to form cities as a form of protection against marauding barbarian armies. Preindustrial Cities Preindustrial cities had important political and economic functions and evolved to become well-defined political units. Cities as Political Centers While ancient cities may have arisen organically as trading centers, preindustrial cities evolved to become well defined political units, like today’s states. During the European Middle Ages, a town was as much a political entity as a collection of houses. However, particular political forms varied. In continental Europe, some cities had their own legislatures. In the Holy Roman Empire, some cities had no other lord than the emperor. In Italy, medieval communes had a state-like power. In exceptional cases like Venice, Genoa, or Lübeck, cities themselves became powerful states, sometimes taking surrounding areas under their control or establishing extensive maritime empires. Similar phenomena existed elsewhere, as in the case of Sakai, which enjoyed a considerable autonomy in late medieval Japan. For people during the medieval era, cities offered a newfound freedom from rural obligations. City residence brought freedom from customary rural obligations to lord and 13 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 community (hence the German saying, “Stadtluft macht frei,” which means “City air makes you free”). Often, cities were governed by their own laws, separate from the rule of lords of the surrounding area. Trade Routes Not all cities grew to become major urban centers. Those that did often benefited from trade routes—in the early modern era, larger capital cities benefited from new trade routes and grew even larger. While the city-states, or poleis, of the Mediterranean and Baltic Sea languished from the 16th century, Europe’s larger capitals benefited from the growth of commerce following the emergence of an Atlantic trade. By the early 19th century, London had become the largest city in the world with a population of over a million, while Paris rivaled the well-developed regional capital cities of Baghdad, Beijing, Istanbul, and Kyoto. But most towns remained far smaller places—in 1500 only about two dozen places in the world contained more than 100,000 inhabitants. As late as 1700 there were fewer than 40, a figure which would rise thereafter to 300 in 1900. A small city of the early modern period might have contained as few as 10,000 inhabitants. Industrial Cities During the industrial era, cities grew rapidly and became centers of population and production. The growth of modern industry from the late 18th century onward led to massive urbanization and the rise of new, great cities, first in Europe, and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas. In 1800, only 3% of the world’s population lived in cities. Since the industrial era, that figure, as of the beginning of the 21st century, has risen to nearly 50%. The United States provides a good example of how this process unfolded; from 1860 to 1910, the invention of railroads reduced transportation costs and large manufacturing centers began to emerge in the United States, allowing migration from rural to urban areas. Rapid growth brought urban problems, and industrial-era cities were rife with dangers to health and safety. Rapidly expanding industrial cities could be quite deadly, and were often full of contaminated water and air, and communicable diseases. Living conditions during the Industrial Revolution varied from the splendor of the homes of the wealthy to the squalor of the workers. Poor people lived in very small houses in cramped streets. These homes often 14 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 shared toilet facilities, had open sewers, and were prone to epidemics exacerbated by persistent dampness. Disease often spread through contaminated water supplies. In the 19th century, health conditions improved with better sanitation, but urban people, especially small children, continued to die from diseases spreading through the cramped living conditions. Tuberculosis (spread in congested dwellings), lung diseases from mines, cholera from polluted water, and typhoid were all common. The greatest killer in the cities was tuberculosis (TB). Archival health records show that as many as 40% of working class deaths in cities were caused by tuberculosis. The Structure of Cities Urban structure is the arrangement of land use, explained using different models. Urban Structure Models Grid In grid models, land is divided by streets intersect at right angles, forming a grid. Grid plans are more common in North American cities than in Europe, where older cities tend to be build on streets that radiate out from a central square or structure of cultural significance. Grid plans facilitate development because developers can subdivide and auction off large parcels of land. The geometry yields regular lots that maximize use and minimize boundary disputes. However, grids can be dangerous because long, straight roads allow faster automobile traffic. In the 1960s, urban planners moved away from grids and began planning suburban developments with dead ends and cul-de-sacs. Concentric Ring Model The concentric ring model was postulated in 1924 by sociologist Ernest Burgess, based on his observations of Chicago. It draws on human ecology theories, which compared the city to an ecosystem, with processes of adaptation and assimilation. Urban residents naturally sort themselves into appropriate rings, or ecological niches, depending on class and cultural assimilation. The innermost ring represents the central business district (CBD), called Zone A.. It is surrounded by a zone of transition (B), which contains industry and poorer-quality housing. The third ring (C) contains housing for the working-class—the zone of independent workers’ homes. The fourth ring (D) has newer and larger houses occupied by the middleclass. The outermost ring (E), or commuter’s zone, is residential suburbs. 15 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Sectoral In 1939, the economist Homer Hoyt adapted the concentric ring model by proposing that cities develop in wedge-shaped sectors instead of rings. Certain areas of a city are more attractive for various activities, whether by chance or geographic/environmental reasons. As these activities flourish and expand outward, they form wedges, becoming city sectors. Like the concentric ring model, Hoyt’s sectoral model has been criticized for ignoring physical features and new transportation patterns that restrict or direct growth. Multiple Nuclei The multiple nuclei model was developed in 1945 to explain city formation after the spread of the automobile. People have greater movement due to increased car ownership, allowing for the specialization of regional centers. A city contains more than one center around which activities revolve. Some activities are attracted to particular nodes while others try to avoid them. For example, a university node may attract well-educated residents, pizzerias, and bookstores, whereas an airport may attract hotels and warehouses. Incompatible activities will avoid clustering in the same area. Irregular Pattern The irregular pattern model was developed to explain urban structure in the Third World. It attempts to model the lack of planning found in many rapidly built Third World cities. This model includes blocks with no fixed order; urban structure is not related to an urban center or CBD. Alternate Uses of “Urban Structure” Urban structure can also refer to urban spatial structure; the arrangement of public and private space in cities and the degree of connectivity and accessibility. In this context, urban structure is concerned with the arrangement of the CBD, industrial and residential areas, and open space. A city’s central business district (CBD), or downtown, is the commercial and often geographic heart of a city. In North America, this is referred to as “downtown” or “city center. ” The downtown area is often home to the financial district, but usually also contains entertainment and retail. CBDs usually have very small resident populations, but populations are increasing as younger professional and business workers move into city center apartments. An industrial park is an area zoned and planned for the purpose of industrial development. They are intended to attract business by concentrating dedicated infrastructure to reduce 16 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 the per-business expenses. They also set aside industrial uses from urban areas to reduce the environmental and social impact of industrial uses and to provide a distinct zone of environmental controls specific to industrial needs. Urban open spaces provide citizens with recreational, ecological, aesthetic value. They can range from highly maintained environments to natural landscapes. Commonly open to public access, they may be privately owned. Urban open spaces offer a reprieve from the urban environment and can add ecological value, making citizens more aware of their natural surroundings and providing nature to promote biodiversity. Open spaces offer aesthetic value for citizens who enjoy nature, cultural value by providing space for concerts or art shows, and functional value—for example, by helping to control runoff and prevent flooding. The Process of Urbanization Urbanization is the process of a population shift from rural areas to cities, often motivated by economic factors. Urbanization and rural flight Urbanization is the process of a population shift from rural areas to cities. During the last century, global populations have urbanized rapidly: ● 13% of people lived in urban environments in the year 1900 ● 29% of people lived in urban environments in the year 1950 One projection suggests that, by 2030, the proportion of people living in cities may reach 60%. Rural and Urban World Population: Over time, the world’s population has become less rural and more urban. Urbanization tends to correlate positively with industrialization. With the promise of greater employment opportunities that come from industrialization, people from rural areas will go to cities in pursuit of greater economic rewards. Another term for urbanization is “rural flight. ” In modern times, this flight often occurs in a region following the industrialization of agriculture—when fewer people are needed to bring the same amount of agricultural output to market—and related agricultural services and industries are consolidated. These factors negatively affect the economy of small- and middle-sized farms and strongly reduce the size of the rural labor market. Rural flight is exacerbated when the population decline leads to the loss of rural services (such as business 17 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 enterprises and schools), which leads to greater loss of population as people leave to seek those features. As more and more people leave villages and farms to live in cities, urban growth results. The rapid growth of cities like Chicago in the late nineteenth century and Mumbai a century later can be attributed largely to rural-urban migration. This kind of growth is especially commonplace in developing countries. Urbanization occurs naturally from individual and corporate efforts to reduce time and expense in commuting, while improving opportunities for jobs, education, housing, entertainment, and transportation. Living in cities permits individuals and families to take advantage of the opportunities of proximity, diversity, and marketplace competition. Due to their high populations, urban areas can also have more diverse social communities than rural areas, allowing others to find people like them. Economic and Environmental Effects of Urbanization Urbanization has significant economic and environmental effects on cities and surrounding areas. As city populations grow, they increase the demand for goods and services of all kinds, pushing up prices of these goods and services, as well as the price of land. As land prices rise, the local working class may be priced out of the real estate market and pushed into less desirable neighborhoods – a process known as gentrification. Growing cities also alter the environment. For example, urbanization can create urban “heat islands,” which are formed when industrial and urban areas replace and reduce the amount of land covered by vegetation or open soil. In rural areas, the ground helps regulate temperatures by using a large part of the incoming solar energy to evaporate water in vegetation and soil. This evaporation, in turn, has a cooling effect. However in cities, where less vegetation and exposed soil exists, the majority of the sun’s energy is absorbed by urban structures and asphalt. During the day, cities experience higher surface temperatures because urban surfaces produce less evaporative cooling. Additional city heat is given off by vehicles and factories, as well as industrial and domestic heating and cooling units. Together, these effects can raise city temperatures by 2 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit (or 1 to 6 degrees Celsius). Suburbanization and Counterurbanization Recently in developed countries, sociologists have observed suburbanization and counterurbanization, or movement away from cities. These patterns may be driven by transportation infrastructure, or social factors like racism. In developed countries, people are able to move out of cities while still maintaining many of the advantages of city life (for 18 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 instance, improved communications and means of transportation). In fact, counterurbanization appears most common among the middle and upper classes who can afford to buy their own homes. Race also plays a role in American suburbanization. During World War I, the massive migration of African Americans from the South resulted in an even greater residential shift toward suburban areas. The cities became seen as dangerous, crime-infested areas, while the suburbs were seen as safe places to live and raise a family, leading to a social trend known in some parts of the world as “white flight. ” Some social scientists suggest that the historical processes of suburbanization and decentralization are instances of white privilege that have contributed to contemporary patterns of environmental racism. In the United States, suburbanization began in earnest after World War II, when soldiers returned from war and received generous government support to finance new homes. Suburbs, which are residential areas on the outskirts of a city, were less crowded and had a lower cost of living than cities. Suburbs grew dramatically in the 1950s when the U.S. interstate highway system was built, and automobiles became affordable for middle class families. Around 1990, another trend emerged known as counterurbanization, or “exurbanization”. The wealthiest individuals began living in nice housing far in rural areas (as opposed to forms). Suburbanization may be a new urban form.Rather than densely populated centers, cities may become more spread out, composed of many interconnected smaller towns. Interestingly, the modern U.S. experience has gone from a largely rural country, to a highly urban country, to a country with significant suburban populations. U.S. Urban Patterns The U.S. Census Bureau classifies areas as urban or rural based on population size and density. Different international, national, and local agencies may define “urban” in various ways. For example, city governments often use political boundaries to delineate what counts as a city. Other definitions may consider total population size or population density. Different definitions may also set various thresholds, so that in some cases, a town of just 2,500 may count as an urban city, whereas in other contexts, a city may be defined as having at least 50,000 people. Other agencies may define “urban” based on land use: places count as urban if they are built up with residential neighborhoods, industrial sites, railroad yards, cemeteries, airports, golf courses, and similar areas. Using this sort of definition, in 1997, the U.S. Department of Agriculture tallied over 98,000,000 acres of “urban” land. In spite of these competing definitions, in the United States “urban” is officially defined following guidelines set by the U.S. Census Bureau. The Census Bureau defines “urban areas” as areas with a population density of at least 1,000 people per square mile and at least 2,500 19 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 total people. Urban areas are delineated without regard to political boundaries. Because this definition does not consider political boundaries, it is often used as a more accurate gauge of the size of a city than the number of people who live within the city limits. Often, these two numbers are not the same. For example, the city of Greenville, South Carolina has a city population under 60,000 and an urbanized area population of over 300,000, while Greensboro, North Carolina has a city population over 200,000 and an urbanized area population of around 270,000. That means that Greenville is actually “larger” for some intents and purposes, but not for others, such as taxation, local elections, etc. As of December, 2010, about 82% of the population of the United States lived within the boundaries of urbanized area. Combined, these areas occupy about 2% of the land area of the United States. The majority of urbanized area residents are suburbanites; core central city residents make up about 30% of the urbanized area population (about 60 million out of 210 million). In the United States, the largest urban area is New York City, with over 8 million people within the city limits and over 19 million in the urban area. The next five largest urban areas in the United States are Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and Boston. The Rural Rebound During the 1970s and again in the 1990s, the rural population rebounded in what appeared to be a reversal of urbanization. The rural rebound refers to the movement away from cities to rural and suburban areas. Urbanization tends to occur along with modernization, yet in the most developed countries many cities are now beginning to lose population. In the United States in the 1970s, demographers observed that the rural population was actually growing faster than urban populations, a phenomenon they labeled the “rural rebound. ” This trend reversed in the 1980s, due in part to a recession that hit farmers particularly hard. But again in the 1990s, rural populations appeared to be gaining at the expense of cities. Indeed, in the last 50 years, about 370 cities worldwide with more than 100,000 residents have undergone population losses of more than 10%, and more than 25% of the depopulating cities are in the United States. Rather than moving to rural areas, most participants in the so-called the rural rebound migrated into new, rapidly growing suburbs. The rural rebound, then, may be more evidence of the importance of suburbanization as a new urban form in the most developed countries. Suburbanization Suburbanization is a general term that refers to the movement of people from cities to surrounding areas. However, the suburbanization that took place after 1970 was different 20 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 from the suburbanization that had occurred earlier, after World War II. In this more recent wave of suburbanization, people moved beyond the nearby suburbs to farther-away towns. Sociologists have invented several new categories to describe these new types of suburban towns; two of the most notable are ex-urbs and edge cities. The expression exurb (for “extra-urban”) refers to a ring of prosperous communities beyond a city’s suburbs. Often, these communities are commuter towns or bedroom communities. Commuter towns are primarily residential; most of the residents commute to jobs in the city. They are sometimes called bedroom communities because residents spend their days away in the cities and only come home to sleep. In general, commuter towns have little commercial or industrial activity of their own, though they may contain some retail centers to serve the daily needs of residents. Although most exurbs are commuter towns, most commuter towns are not exurban. Exurbs vary in wealth and education level. In the United States, exurban areas typically have much higher college education levels than closer-in suburbs, though this is not necessarily the case in other countries. They typically have average incomes much higher than nearby rural counties, reflecting the urban wages of their residents. Although some exurbs are quite wealthy even compared to nearer suburbs or the city itself, others have higher poverty levels than suburbs nearer the city. This may happen especially where commuter towns form because workers in a region cannot afford to live where they work and must seek residency in another town with a lower cost of living. For example, during the “dot com” bubble of the late twentieth century, housing prices in California cities skyrocketed, spawning exurban growth in adjacent counties. White Flight Sociologists have posited many explanations for counterurbanization, but one of the most debated is whether suburbanization is driven by white flight. The term white flight was coined in the mid-twentieth century to describe suburbanization and the large-scale migration of whites of various European ancestries, from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban regions. During the first half of the twentieth century, discriminatory housing policies often prevented blacks from moving to suburbs; banks and federal policy made it difficult for blacks to get the mortgages they needed to buy houses, and communities used restrictive housing covenants to exclude minorities. White flight during this period contributed to urban decay, a process whereby a city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude. Symptoms of urban decay include depopulation, abandoned buildings, high unemployment, crime, and a desolate, inhospitable landscape. White flight contributed to the draining of cities’ tax bases when 21 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 middle-class people left, exacerbating urban decay caused in part by the loss of industrial and manufacturing jobs as they moved into rural areas or overseas where labor was cheaper. More recently, the concept has been extended to newer forms of suburbanization, including migration from urban to rural areas and to exurbs. In a similar vein, some demographers have described the rural rebound, and the newest waves of suburbanization, as a form of ethnic balkanization, in which different ethnic groups (not only whites) sort themselves into racially homogeneous communities. These phenomena, however, are not so clearly driven by the restrictive policies, laws, and practices that drove the white flight of the first half of the century. Models of Urban Growth Models of urban growth try to balance the advantages and disadvantages of cities’ large sizes. Cities are dynamic places—they grow, shrink, and change. Sociologists have developed different theories for thinking about how urban populations change. Growth Machine Theory The growth machine theory of urban growth says urban growth is driven by a coalition of interest groups who all benefit from continuous growth and expansion. First articulated by Molotch in 1976, growth machine theory took the dominant convention of studying urban land use and turned it on its head. The field of urban sociology had been dominated by the idea that cities were basically containers for human action, in which actors competed among themselves for the most strategic parcels of land, and the real estate market reflected the state of that competition. Growth machine theory reversed the course of urban theory by pointing out that land parcels were not empty fields awaiting human action, but were associated with specific interests—commercial, sentimental, and psychological. In other words, city residents were not simply competing for parcels of land; they were also trying to fulfill their particular interests and achieve specific goals. In particular, cities are shaped by the real estate interests of people whose properties gain value when cities grow. These actors make up what Molotch termed “the local growth machine. ” Urban Sprawl Whether explained by older theories of natural processes or by growth machine theory, the fact of urban growth is undeniable: throughout the twentieth century, cities have grown 22 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 rapidly. In some cases, that growth has been poorly controlled, resulting in a phenomenon known as urban sprawl. Urban sprawl entails the growth of a city into low-density and autodependent rural land, high segregation of land use (e.g., retail sections placed far from residential areas, often in large shopping malls or retail complexes), and design features that encourage car dependency. Urban sprawl’s segregated land use means that the places where people live, work, shop, and relax are far from one another, which usually makes walking, public transit, or bicycling impractical. As a result, residents must use an automobile. Urban sprawl tends to include low population density: single family homes on large lots instead of apartment buildings, single story or low-rise buildings instead of high-rises, extensive lawns and surface parking lots, and so on. Critics of urban sprawl argue that it creates an inhospitable urban environment and that it encroaches on rural land, potentially driving up land prices and displacing farmers or other rural residents. Urban sprawl is also associated with negative environmental and public health effects, many of which are related to automobile dependence: increases in personal transportation costs, air pollution and reliance on fossil fuel, increases in traffic accidents, delays in emergency medical services response times, and decreases in land and water quantity and quality. Urban Decay Some have suggested that urban sprawl is driven by consumer preference; people prefer to live in lower density, quieter, more private communities that they perceive as safer and more relaxed than urban neighborhoods. Such preferences echo a common strain of criticism of urban life, which tends to focus on urban decay. According to these critics, urban decay is caused by the excessive density and crowding of cities, and it drives out residents, creating the conditions for urban sprawl. BROKEN WINDOWS An alternative theory suggests that density does not cause crime, and crime does not cause people to leave the city; when people leave, city neighborhoods are abandoned and neglected, resulting in crime and decay. This theory, known as the “broken windows theory,” argues that small indicators of neglect, such as broken windows and unkempt lawns, promote a feeling that an area is in a state of decay. Anticipating decay, people likewise fail to maintain their own properties. 23 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 RESPONSES TO DECAY Cities have responded to urban decay and urban sprawl by launching urban renewal programs. Two specific types of urban renewal programs—New Urbanism and smart growth—attempt to make cities more pleasant and livable. Smart growth programs draw urban growth boundaries to keep urban development dense and compact. In addition to increasing the density of cities, urban growth boundaries can protect the surrounding farmland and wild areas. Smart growth programs often incorporate transit-oriented development goals to encourage effective public transit systems and make bicyclers and pedestrians more comfortable. New Urbanism is an urban design movement that promotes walkable neighborhoods with a range of housing options and job types. As an approach to urban planning, it encompasses principles such as traditional neighborhood design and transit-oriented development. A neighborhood designed along New Urbanist principles would have a discernible center (such as a square or a green) with a transit stop nearby. Most homes would be within a fiveminute walk of the center and would provide a variety of housing options, including houses, row houses, and apartments to encourage the mixing of younger and older people, singles and families, and poor and wealthy. TASK 2: Read the materials provided for this task and create an infographic. TASK INFORMATION: Please take note of the following in formulating your output. 1. Read thoroughly the reading materials provided. 2. Create a n infographic on the impact of urban development in Asian cities and its underlying problems. 3. Below is a sample infographic: 24 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 https://www.adb.org/news/infographics/fostering-growth-and-inclusion-asia-cities OUTPUT CONDITION: Take note of the following in crafting your infographic. 1. The task can be computer generated or drawn in this module. Please make sure to use readable fonts. 2. For the purpose of readability, electronic outputs should be encoded using Century Gothic, with font size of at least 18-20 px. Images shall improve the 25 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 appearance of the output, but do not forget to cite these images at the bottom of your infographic or at the end of your presentation (APA format). 3. You may draw your output and take a screenshot of it. 4. Outputs may be sent again to the official email address of the professor with the subject “SURNAME_SUBJECT_TASK2” as back-up in case of internet connectivity issues. RUBRIC OF ASSESSMENT: Take time to review the rubric of evaluation which inform you of the how to your Task 2 would be graded YOUR POINTS AND NOTES (to be accomplished by the teacher) ANSWER SHEET: Place your infographic here. 26 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 READING MATERIAL NO. 4 Rethinking Asian Cities and Urbanization: Four Transformations in Four Decades by Yue-man Yeung https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10225706.2011.577975 Economic transformation As Asia entered the 1970s, it was a tumultuous period of the Cold War, the Vietnam War and the oil crises. By that time Japan had already completed its postWorld War II economic miracle from the debris of a defeated nation. It appeared poised for leading the region and the world for further economic growth (Vogel 1986). The newly industrializing countries of Asia, or better known as the Four Little Dragons, namely Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, were beginning to make their marks on the global economy by pursuing their style of export-oriented manufacturing. The 1980s saw the emergence of the so-called Asian tigers represented by Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam. However, it was the recent rise of China and India that has elevated the prospect of Asia being able to enhance its global significance in the twenty-first century. In the two decades prior to 1980, Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan witnessed a 13-, 11-, and 14-fold increase, respectively, in per capita gross national product, as they skillfully tapped the world market (Yeung 1988a, p. 155). Much of the economic growth was city-led, with export processing zones adopted initially as a vehicle to channel a range of consumer goods to the world market under regimes of tax relief (Antione 1984, Kundra 2000). The Asian rush to tap the world market took an active turn when China adopted its open-door policy and economic reforms in 1978 and Vietnam similarly adopted a policy of doi moi in 1986. In South Asia, too, India in 1991 forsook its erstwhile conservative import substitution policy and lowered tariff barriers which had hitherto kept multinationals at bay. This was followed by the globalization of consumption patterns and the explosion of South Asian economies, with a large range of “modern” products ranging from IT services to nuclear warheads (Bradnock and Williams 2002, Lakhera 2008). The entire Asian region has changed in its orientation and complexion, having via their cities connected their economy and their people to the world at large. Asian economies and their people have become more globalized than ever. Closer integration of Asian economies with the world as a consequence of accelerating globalization processes over recent decades has had its pros and cons on the economic 27 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 and social life of the people. When financial globalization in the last decade of the twentieth century was not tempered by the requisite regulatory mechanisms and safeguards, what began as a devaluation of the Thai Baht on 2 July 1997 quickly spread, with contagion effect, from Thailand to South Korea and Indonesia. Indeed, most Pacific Asian countries excepting China were engulfed in an unprecedented and devastating financial crisis. The Asian financial crisis led most Asian countries edging towards the brink but they managed somehow to slowly recover (Yeung 1998a). Another even more ominous financial crisis, this time global in nature and originating in the United States through the subprime meltdown, took Asia by storm in 2008. Signs of recovery in Asia appeared slowly and spottily in 2009 but the whole episode brought home the message of the vulnerability of every country to the shortcomings of the global economy and how Asian countries and cities can be severely and inadvertently affected (Yeung 1998b). Physical transformation On the basis of their sound economic development, most Asian countries have over the past four decades undergone the dramatic physical transformation of their cities. From what used to be pedestrian urban entities, many Asian cities have literally thrust themselves into the forefront of an urban renaissance that has come with more heightened roles played by cities in the era of globalization (Knight 1989, Kim et al. 1997, Yeung 1998c, 2000a, 2000b). The process of urban physical change in Asia can be traced through systemic forces emanating from within individual countries/cities and from global production and distribution chains, although these internal and external drivers of change are increasingly intertwined (Yeung 1996a, 2000a). In the late 1960s, it was fashionable to explain the growth of Asian cities, especially in Southeast Asia, by invoking their growth through a process of urbanization without industrialization, in what T. G. McGee (1967) termed pseudo-urbanization. With the exception of perhaps of Japan, Asian cities were largely about to enter their industrialization phase, with the informal sector being quite prominent in providing employment. Certainly in Southeast Asia, hawkers and vendors played a valuable role in providing vital service and employment opportunities (McGee and Yeung 1977) and low-cost housing provided shelter for the masses (Yeung 1973, 1983, 1985, Yeh and Laquian 1979, Yeung and Wong 2003). The 28 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 informal sector figured even more prominently in South Asia, since even in the 1990s, as much as 40% of India's urban population lived in informal housing, figures exceeded by Pakistan with 58%, including 22% in katchi abadis, a local name for squatter settlements (Bradnock and Williams 2002, p. 231). Indeed, South Asia had the largest concentration of global poverty, accounting for 43.5% of the world's total, with over 500 million people living on less than a dollar a day even in 2000, according to World Bank data (Bradnock and Williams 2002). South Indian intellectuals have provided a critical reappraisal of “mainstream development” and have provided an empirical and rational exposition of poverty by stressing its characterization and measurement, at the same time, pointing out the flawed approach of policy definition (Sen 1981, 1997). Drawing examples from South Asia, Lipton (1977) propounded his urban bias hypothesis by which he submitted the urban world is underrepresented in that sub-region, although the agricultural sector has remained critically important to the majority of the people in South Asia. As relatively young nations which had become independent from colonial rule, most countries in South and Southeast Asia had by the early 1970s entered into a phase of rapid urbanization, with cities, particularly large cities being nurtured as symbols of national unity and national identity (Yeung and Lo 1976, p. xx, Yeung 1976, 1978). With poverty being a pervading problem, urban planning was primarily aimed at improving the basic functions and services of the city. Even as late as 1990, I was commissioned by the World Bank to write a “think piece” to address the subject of the access of the urban poor to basic infrastructure services in Asia. The urban poor across Asia were faced with the common problem of not adequately provided for in basic urban services ranging from water supply, housing, sanitation, transport and so on (Yeung 1991). Urban infrastructure development lagged behind economic development in the region even by the mid-1990s (Yeung 1994, Yeung and Han 1997, pp. 15–31). In any event, large, capital and “million” cities in the region were better off in physical infrastructure provisions because of their relative importance in their countries and their competitive advantage (Yeung 1988a, Misra and Misra 1998, Laquian et al. 2007). Yet large cities were confronted with incessant rural-urban migration. It was not surprising that many cities attempted to control their population growth (Yeung 1986, 2002a) and sought ways to improve metropolitan management (Yeung 1995e). As early as 1970, Jakarta attempted to “close” the city by putting in place policies to limit city-bound migration, complemented by a long-standing policy of transmigration to direct movement 29 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 of population from congested Java to other less populated islands. Seoul instituted tax measures in 1973 to discourage the arrival of new migrants. Since 1958, China effectively sealed off rural-urban migration through a stringent household registration system until its relaxation in 1984 (Chan 2009). Singapore even controlled the entry of vehicles into the central city area to minimize traffic congestion by initiating an Area Licensing Scheme since 1975. In fact, cities became centres of change in Asia, with no shortage of ideas to improve urban growth and management (Dwyer 1972, Yeung 1990). In terms of the speed and scale of urban change, no country can compare with China in its urban transformation in recent decades. China's urban population of 172 million in 1978 ballooned to 593.8 million in 2007. Within the same period, its level of urbanization leaped from 18% in 1978 to 45% in 2007, at a growth rate of almost 1% per year; the number of cities exploded from 192 in 1978 to 651 in 2007 (NBSC, various years). The number of cities has grown especially rapidly since the country adopted economic reforms in 1978. By 2006, there were 48 “million” cities, accounting for 41.53% of the total non-agricultural urban population in China (Gu et al. 2008, p. 30). While China's urbanization since the onset of economic reforms was driven by rural industrialization and town development, since the mid-1990s, urban spaces have been reproduced through a city-based and land-centred process of urbanization led by large cities (Lin 2007). During this period, the conversion of non-agricultural land to urban use has been widespread and historically intense, although recent measures have kept rural land conversion in check (Ho and Lin 2004, Lin and Ho 2005). In recent studies of urban development and urban space in China, the interplay of power between the state and the market is highlighted, as institutions, laws and regulatory controls are being put in place (McGee et al. 2007, Wu et al. 2007). Without a doubt, Chinese cities have grown the fastest and changed beyond recognition, with many exciting achievements and some wasteful investments (Yeung 2007a). Even the study of China's urbanization has progressed at an impressive pace, with admirable scholarship and tangible results to boot (Gu et al. 2008). With respect to external forces that have been increasingly impacting on urban change in Asia, the phenomenon had become more prominent from the late 1980s. McGee has expounded the thesis of extended metropolitan region (EMR), drawing attention to the desakota process of interaction between urban and rural areas (Ginsburg et al. 1991). Integrated rural-urban economic growth may stretch anywhere from 50 to 100 km from the 30 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 city centre. External and international firms seek business opportunities through the new international division of labour, where cheaper land and labour in Asian cities attract supply chains of transnational corporations. This process has been prevalent in Southeast Asia, where mega-urban regions have emerged (McGee and Robinson 1995, Yeung 2007c) and in China, as exemplified in a case study of Kunshan in the Lower Yangtze Delta (Marton 1998). Where globalization processes especially favor, world cities or global cities have loomed large in the current phase of globalized economic development. Sassen (1991) has used Tokyo as one of the examples to expound her thesis of global cities, but world cities have been more appealing to scholars and planners in Asia. Either type, they symbolize a level of global reach and integration of Asian cities to global economic, political and cultural processes not previously experienced. The Asian region has its fair share of world cities, with Tokyo, Hong Kong and Singapore having reached the highest level of importance (Beaverstock et al. 1999). Hong Kong has gone one step further in employing the label – world city – to publicize the city since 1999 but the planning took more than a decade in its run-up to the handover in 1997 (Yeung 1997a). In order to enhance their competitiveness and world fame, many Asian cities have been engaged in a process to make themselves known to the world, strategically targeting at potential investors and visitors. Otherwise known as place-making or place-marketing, Asian cities have favored mega-projects, with funding often coming from international sources, to promote their long-term interests. Kuala Lumpur's city centre and the Petronas Twin Towers, Tokyo's Teleport Town, the commercial and cultural hub at Marina Centre in downtown Singapore, and Shanghai's Pudong New Area are some shining examples (Olds 1995, Yeoh 2005). In addition, Tokyo's and Hong Kong's Disneyland, Osaka's United Studio and Macao's Venetian stand for another kind of attraction and place-making. Still another level of world fame is garnered by some Asian cities hosting global events such as the Olympic Games (Tokyo 1964, Seoul 1996, Beijing 2008), World Exposition (Shanghai 2010) and the World Cup (South Korea and Japan 2002). In fact, world city formation can be achieved through a deliberate process of purposeful investment, in R&D in a drive towards new technology and knowledge, in infrastructure investment such as building huge and futuristic airports, container ports, intelligent buildings 31 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 and first rate commercial land uses, and such like (Lo and Yeung 1998, pp. 132–154). Indeed, foreign demands for better services and facilities in Asian cities have converged on local needs to improve infrastructure facilities along many fronts. Within large cities, urban highways and elevated networks are complemented by subways. The outstanding example is China, where at least 15 cities are building subway lines and a dozen more are planning them. The most ambitious construction plans have been made in Guangzhou, which is building the world's largest and most advanced subway system. Construction is going non-stop around the clock in Guangzhou to reach a long-term plan of 500 miles of subways and light rail routes, from the present 71 miles of subway lines (New York Times, 17 March 2009). China's grandiose plans in subway construction and automobile manufacturing go hand in hand, with total sales of automobiles outstripping the United States in the first six months of 2009, at 6.1 million vehicles versus USA's 4.8 million vehicles (Wong 2009). These stand in stark contrast to India, where in Mumbai, its population of 19 million is struggling daily to move about the mega-city without being able to count on a better day. The city has no plans to build any subway system, an understanding based on my field reconnaissance in Mumbai in early 2009. Along with the physical changes of Asian cities that have been touched upon, they are being suburbanized, motorized, westernized and globalized, especially for cities located in East and Southeast Asia. The convergence with the western model has been observed of urban development in Southeast Asia (Dick and Rimmer 1998), but much of the same has been afoot or already in place in East Asia. For the most obvious physical change of Asian cities, the best indicator is perhaps the competition to vie for the distinction of possessing the tallest building in the world. This race is never ending, as the tallest building fame comes and goes. Of the 10 tallest buildings in the world in 2009, nine were located in Asia. It is noteworthy that six of the 10 tallest buildings are located in cities in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, making it perhaps a mark of Chinese cities.3 As a consequence, the skyline of many Asian cities, notably Hong Kong and Shanghai, is stunningly beautiful. The physical transformation of Asian cities has largely occurred during the past two decades. The most dramatic of all the urban physical changes can be epitomized by Dubai, of the United Emirates. A picture showing the main thoroughfare of the city in 1990 is completely transformed in another shot taken in 2003. Dubai stands for the most ambitious physical engineering change of any Asian city. It boasts of having the world's largest indoor 32 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 ski facility, the largest shopping mall, the tallest building, the biggest amusement park and other superlatives. However, even Dubai has not escaped the onslaught of the recent global financial crisis. It was reported by Time magazine (25 May 2009) that property prices in 2009 had declined to 2007 levels and expatriates had been leaving in droves. Social transformation Cities exist more than their physical form but they inhabit dreamlike space of past and present, individual and collective memories (Robinson 2000, p. 108). It is people who give meaning to cities entailing associational life, social conviviality, identity and power (Ho and Douglass 2008). However, these were not the immediate concerns of urban life in Asia in the early 1970s when poverty was an overriding challenge for governments and international assistance bodies to tackle. A sample of some of the policy foci and research projects included low-cost housing (Yeung 1973, 1983, 1985), community participation in delivering urban services (Yeung and McGee 1986) and employment and livelihood for the urban poor (Yeung 1988b). The policy focus on the urban poor in Asia persisted through the 1990s and beyond (Yeung 1991, 2001a). The exceptionally rapid economic growth in many Asian countries since 1970, as noted earlier, has markedly reduced the incidence of poverty. Overall for Asia, the official poverty rate was reduced from 32% in 1990 to 22% in 2000 (Kabeer 2006). Indeed, recent reports have focused on how past efforts have borne fruit in reducing urban poverty in Asia. Real progress has been made to reduce poverty through partnerships working together to improve slums, networking, providing credit for financing microenterprises and adopting a programme rather than a project approach. Economic growth has accounted for 60% of poverty reduction in Asia (Hamid and Villareal 2001, pp. 237–239). Complementing these efforts have been major advances made by NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) to work in concert with government bodies to improve the livelihood of the urban poor ranging from protecting the environment to meeting basic health needs. NGOs have been exceptionally active in South Asia, notably India and Bangladesh, with the role of women effective in generating positive socio-economic change (Bradnock and Williams 2002). In view of the progress made to reduce poverty, development aid from developed countries itself is being dwarfed significantly by the move 33 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 towards neo-liberalism which became the hallmark of the 1990s and which left its imprint in all countries in South Asia, especially Nepal and Bangladesh, and across the south (Bradnock and Williams 2002, p. 270). Poverty alleviation in the urban areas in Southeast Asia has been no less impressive, where the work of NGOs also scored high marks (Porio 1997). Some of these NGO activities have been inspired and supported by global transnational movements which have take precedence over indigenous funding and efforts. Urban social movements related to protecting the environment and improving low-cost housing are examples that have enjoyed widespread support. Over the years the persistence of poverty has been a powerful motive for Asian population to take a key decision to migrate, both within their countries and to other countries. Although seeking better economic opportunities has been commonly identified as the primary motive, many people have also migrated within their countries because of warfare, national social movements and the like. During the past decades, Asia has painfully gone through many wars for different reasons, such as the Vietnam War (1959–1975), the Bangladesh War of Independence (1971), Indonesia's war over Aceh (2001–2004), the IranIraq War (1980–1988) and the First Gulf War (1990–1991). The rustification programme of educated youth, otherwise known as xiafeng, in China involved some 12 million youths going to the countryside for a learning experience and contribution to nation building at the height of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Many youths returned to Shanghai and other large cities after the tumultuous period concluded (Ivory and Lavely 1977). Internal migration in many of the Asian countries mentioned above was sizeable and has had huge social, political and economic significance (Yeung 2002a). In Vietnam and countries within South Asia, post-independence migration has been economically and socially motivated. However, with the Middle East having emerged as a favorite destination with its petrol dollar after the oil crises in the 1970s, international migration from countries in South Asia, the Philippines, South Korea and others has been substantial and sustained. Kerala in India and Sri Lanka are two South Asian regions that have been identified as having their social and cultural landscapes dominated by migration to the Gulf countries of West Asia since the early 1970s. International migration has introduced new styles of consumption, production of novel forms of social differentiation in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan (Osella and Gardner 2004). It has also led to marked social transformation in 34 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 all countries concerned, in which flows of resources (such as remittances) have gone from centres of capital into their peripheries. In addition, social and power relations have changed in the place of origin, and new consumption tastes and patterns have taken root (Bolaria and Bolaria 1997). The phenomenon of transnational domestic workers has become a familiar landscape in high-income countries and economies such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Taipei and countries in the Middle East (Huang et al. 2005). With the kind of rapid economic transformation that has occurred in Asia, it is to be expected that society in many countries has been undergoing revolutionary change. Like the ancient “Silk Road” that connected China to the outside world, the new Silk Road is projected to connect Asia to the West. A rapid and transforming change is coming to pass in many Asian cities. A new middle class is said to have emerged in many countries and cities, especially large cities. Although the middle class is a contested concept, Smith (2002) has estimated that India has probably 300 million who can be considered as the middle class, and China has about 110 million, or about 15% of the employed population. Professional middle class youth has been observed to be important in directing social change in Vietnam, especially in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (King et al. 2009). Similarly, Singapore, Manila, Kuala Lumpur and other cities in Southeast Asia have been transformed in the past decade by the expansion of consumer culture, along with a different urban landscape, by virtue of the “new middle classes” (Clammer 2003, p. 407). The proliferation of posh and large shopping malls in cities ranging from Beijing, Manila, Bangkok to Jakarta is a new social and economic phenomenon of Asian cities (Yeung 2002b, 2002c). A reflection of the how better off Asians are, using ownership of key commodities as indicators, will testify to the vastly changed and rapidly affluent society. In television sets per 1000 people, the figures for 1970 and 2003, respectively, are dramatically improved for China (1, 350), India (0, 83), (Sri Lanka, 0, 117) which started with almost nothing, and substantially improved for Hong Kong (113, 504), South Korea (19, 458) and Japan (337, 795), with the United States (395, 938) used for comparison. Similarly, in ownership of personal computers per 1000 people, the figures for 1988 and 2003, respectively, are impressive for China (0.3, 27.6), India (0.2, 7.2), Sri Lanka (0.2, 13.2), which started almost from zero, and indicative of very rapid change in Hong Kong (25.7, 422), South Korea (11.2, 558) and Japan (41.6, 382.2), which are miles ahead from the previous group of countries, with the United States (184, 658.9) again used for comparison (Mostrous et al. 2006, p. 11). It has been rationalized that 35 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Asia has become an indispensable part of a complex global economy, having come of age during a period of explosive globalization and technological change. Asia has become an engine of global economic growth, with a high savings rate and an increasing bias towards consumption. The world needs a new growth engine in the twenty-first century and Asia has the ability to develop a sustainable and consumer-based economic growth model (Brahm 2001, Mostrous et al. 2006). In the midst of growing affluence in Asia, extreme poverty persists and has become more pronounced in rural areas. Table 3 shows disaggregated data for three largest countries in Asia. In both China and Indonesia, both urban and rural poverty gaps have sharply declined since the early 1990s, a reflection of their very rapid economic transition over the past two decades. The difference is much less marked in India. Asian urbanization has become more economically and socially polarized, as measured by the Gini index. Data for a few selected countries in South Asia show a worsening trend. Between 1991 and 2000, the Gini coefficient as a measure for income inequality in Bangladesh rose from 0.30 to 0.41, Sri Lanka from 0.32 to 0.40 from 1990 to 2002, and Nepal from 0.34 to 0.39 between 1995 and 2003 (Kabeer 2006, p. 64). The sharpest rise in the Gini index was recorded by China, which saw the index rose from 29.2 in 1990 to 35.4 in 2005. The biggest drop in the Gini index occurred in Malaysia, whose index dropped from 43.9 in 1990 to 37.9 in 2005, but the Philippines and Thailand remained stable and high over the said period, with the score in the low 40s in 2005 (ADB 2008, p. 122). In China it has be reported that increasing social inequality has been a cause for growing instability. Social unrest has been more frequent now than a decade ago when society was less affluent (Huang 2008). As the new global economy began to unfold and integrate Asian cities and economies, a literature began to accumulate on subjects such as global restructuring (Yeung 1995a, 1996a, Lo and Yeung 1996, pp. 17–47), global processes (Bishop et al. 2003), the relationship between globalization and world cities (Yeung 1995b, 1995c, 1995d), changing labour markets (Brocks 2006), minorities and civic society (Hasegawa and Yoshihara, 2008), links between international and local development (Yusuf et al. 2001) and the role of transnational corporations (H. Yeung 1998, 2002). Much of the global capital that has been driving the Asian growth over the past quarter century has been derived from foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI inflows as a measure of 36 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 its percentage of the GDP, for the period 1980–1985 came to 18.72% in Singapore and 6.9% in Hong Kong, but only 0.87% in China and 0.14% in India. These percentages for the period 1994–1997 for the four countries in question were, respectively, 27.81, 9.93, 13.24 and 2.46, indicating that both Singapore and Hong Kong continued to depend on substantial FDI inflows, and China and India, especially the former, have vastly increased the importance of FDI inflows to their economy (Lall & Urata, 2003: 3). China's actual utilization of FDI totaled US $78.34 billion in 2007, a big leap from only US $13.06 billion for the period 1978–1982 (Almanac 2008, p. 17). China's ability to attract FDI far outstripped India, as in 2000, China's FDI inflows totaled US $38.39 billion, compared with US $2.32 billion for India (Brooks and Hill 2004, p. 34). After two decades of being integrated with the global economy, Asian countries have developed rapidly and, consequently, have greatly improved their ability to outsource FDI. Hong Kong has become the second largest source of outward FDI flows in Asia, after Japan. Hong Kong's outward FDI came to US $43.46 billion in 2006, a tremendous improvement on its US $82 million in 1980. China exported US $16.13 billion of FDI in 2006, a far cry from its US $830 million in 1980. The relevant figures for India were US $9.68 billion in 2006, and merely US $4 million in 1980 (Rajan et al. 2008, p. 4). The massive increase of FDI outflows from Asian countries has fully demonstrated the maturity of Asian economies and their growing integration with the global economy. The flow of financial resources has now become circular between Asia and the world, no longer a one-way street. In most Asian countries, a majority of their GDP has been generated by their cities. The extreme cases can be cited of Bangkok (44%), Dhaka (40.9%) and Seoul (24.1%) (IMF, 2009),2 where their classical primacy in their respective countries prevails not only in population but also in economic importance, as shown in the proportion of GDP they contributed to their respective countries. As countries that have recently opened or reopened to world trade and commerce, China and Vietnam both engineered their economic revival from their cities, as recent studies have chronicled and analyzed their major milestones after their openness (Yeung and Hu 1992, Yeung and Sung 1996, Yeung 2004a, 2007a, 2007b, Yeung et al. 2009). Along with globalization, regional cooperation and integration with the global economy have furthered the economic development of Asia by connecting countries/cities within 37 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Asia to world markets. Within East Asia, the development of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) since 1967, APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation) since 1989 and the run-up to the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area in 2010 have been facilitating regional integration and cooperation and, in the process, have consolidated Asia's global status as a consequence (Yeung 2006). Over the past four decades, economic transformation in Asia has been sustained and progressed in what has been characterized as a flying-geese pattern, with Japan leading the way (Yamazawa 1990). Table 1 shows that between 1970 and 2005, the average annual growth rate of the GDP of most countries in Asia has been at double digits or close to them in all its sub-regions with the exception of South Asia. Even countries in South Asia have enjoyed an average of high single digit growth. The fastest sustained economic growth has been accorded to South Korea, Singapore and Saudi Arabia. The rapid economic growth at the country level has been matched by impressive per capita GDP increases in their own currency over the same period. However, positive change in Asian cities has come from the mindset of the people. As an example, liveable cities with an accent on the quality of life have been espoused by academics and planners. Consequently, the planning agenda has built-in concerns about economic, social and environmental sustainability (Girardet 2004, Yeung 2004c, 2009). Smart growth, compact cities and new urbanism have been invoked from experiences in western countries. People have become more conscious of the effects of climate change, possible sea-water level rises and their negative impacts of Asian coastal cities (Yeung 2001b), limits of combustion technologies and the search for renewable energy and so on. Car ownership is still high in some cities, such as Bangkok (255 cars per 100 persons), Tokyo (250) and Seoul (220) versus some cities much better positioned from an environmental standpoint, represented by Hong Kong (55), Mumbai (50) and Guangzhou (45) (UN-HABITAT 2008, p. 178). These concerns about car ownership and energy consumption are embodied in a new concept of harmonious cities that has been advocated by the UN body, underpinned by two guiding thoughts of equity and sustainability and maintaining social and environmental harmony (UN-HABITAT 2008). In fact, at the Fourth World Urban Forum convened in Nanjing in November 2008, harmonious cities provided an overarching theme to connect cities of the world to take stock of the present to chart their common future (Germain 2009). 38 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Informational transformation One of the distinguishing features of the current phase of globalization from past ones is the fact that it has been driven by new technologies, notably information and communication technologies (ICT). These technologies that until recently were nothing but pipe dreams to many people have been widely adopted and become reality. They have radically changed our lives and the way in which cities function within them and between them. The ease with which people can access, generate, transfer and retrieve information is a new blessing, but it has as well created a digital divide between those who have access to the new technologies and those who have not, often differentiated by economic, educational and locational attributes. In short, Asian cities and their inhabitants are never the same with the advent of the information age. People in the information age have taken many of the recent ICT inventions and conveniences for granted. Imagine a life now without the computer, the cellular phone, emails, digital camera and the like. Yet the Internet's founding can be traced to a message sent on 29 October 1969 from UCLA to Stanford and by 1988, only about 60,000 computers in the world were connected to the Internet (Zittrain 2008, p. 27). The cost of processing information has tremendously cheapened over time. In 1961 a single transistor cost US $10, which is enough to buy almost two million transistors today, which with “rounding to zero” is essentially free of charge. The time-tested Moore's Law accurately predicted that the cost of computer processing would drop by half at least every two years. Indeed, the digital computer and the Internet shrink the price of many forms of work to free (Canon 2009). Over the past few years, the widespread adoption of ICT technologies has occurred in Asia. By 2007, mobile telephones in developing countries in Asia have cornered over 80% of the total telephone market. In the poorer developing countries in the region, most of the expansion in communications has been via mobile telephone connectivity. For example, the banks in the Philippines allow people to pay, receive and transfer money using a mobile telephone (ADB 2008, p. 123). Between 2003 and 2007, the change in telephone lines per 100 people reached between 20 to 40 for most countries in Asia, with the role of fixed lines further eroded (ADB, p. 124). The increase in the number of Internet users per 100 population has similarly been substantial between 2000 and 2007, ranging, respectively, from China 39 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 (1.8, 15.8), Hong Kong (27.8, 55.0), Japan (29.9, 73.5), Macao (13.6, 49.5) to South Korea (40.7, 72.2) in East Asia; Indonesia (0.9, 5.6), Malaysia (21.4, 56.5), the Philippines (2.0, 6.0), Singapore (32.4. 60.9), Thailand (3.8, 21.0) to Vietnam (0.3, 20.5) in Southeast Asia; and Bangladesh (0.1, 0.3), India (0.5, 17.1), Pakistan (0.2, 10.7) to Sri Lanka (0.6, 4.0) (ADB, p. 127). Quite clearly, the level of economic development is positively related to the degree of intensity of Internet users. Another source has reported that of the 1 billion users of the Internet service in the world in December 2008, China ranked first with its 179.7 million users, compared with 60 million in Japan.4 In an information society, the strategic importance of cities, especially world cities and global cities, is to become managerial centres for global activities that can be subsumed under three heads: economic competitiveness and productivity, socio-cultural integration and political representation. First, competitiveness does not mean cost-cutting, but rather increasing productivity, which, in turn, is predicated upon connectivity, innovation and institutional flexibility. Connectivity means being linked to circuits of information and communication; innovation invokes the capacity to generate new knowledge based on a capacity to obtain and process strategic information; and institutional flexibility refers to the internal capacity and external autonomy of local institutions in dealing with supra local entities. Secondly, as globalization extends its homogenizing influences, it is incumbent on nation states and cities to strengthen their cultural and historical identity of territories to cohere with their people and add meaning to their lives. Thirdly, city governments faced with the challenge of authority and power that cross-border flows of capital, goods and services inevitably entail, have to seek a revitalized role through the structural crisis by building new networks of cooperation and solidarity (Borja and Castells 1997, Yeung 2001d). The adoption of new technological innovations for communication and exchange of information has resulted in the new geographies of Asia. Two sectors have been exploding in their growth and influence. The first is telecommunications infrastructure, notably fiber optic cables, and the second is the expansion of regional electronic media, especially television through satellites (Forbes 1997, p. 21). Fiber optics is the preferred technology despite the challenges associated with laying deep-sea cables. By 1995, 50 telecommunications carriers from 34 countries had invested US $3.5 billion in the expanding web of international optical systems in the region. In the present wired world, the concentration of submarine cables in Asia is increasingly pronounced (Malecki and Wei 40 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 2009). A similar rush for satellites is epitomized by Interlsat, the 127-member global consortium, launching the first Pacific satellite in 1996 (Yeung 2001d). With the widespread adoption of technological innovations, a dilemma that has to be addressed in the information age is media ethics in Asia (Iyer 2002). As a consequence, all these developments have greatly advanced the connectivity and quality of life in Asian cities. The emergence of the informational economy has facilitated the globalization of finance. The operation of stock markets across the world, for example, is computer-dependent and closely linked, to such an extent that the stock market crashes in 1987, 1997 and 2008 were to some extent computer-triggered, certainly with the first two. Even mass political protests witnessed over the past decade in cities such as Taipei, Bangkok and Jakarta have been facilitated by the ease and ready transmission of communication (Yeung 2009). Transnational crime of diverse kinds is a fact of life in the global economy that has affected Asian cities. Drug traffic, illicit traffic of weapons, art treasures, human beings, human organs, radioactive materials and money laundering continue to plague cities in the region. Alarmed by the growing trend of cross-border crime, some Asian countries have made the trafficking of drugs a crime punishable by death (Yeung 2001d). Recent ICT technological advances have helped people to change their concept of space and distance, even within Asian cities. The region and its cities have suddenly become much smaller, being traversed by information superhighways across cyberspace. The relationship between ICT, space and place has been played out in the spatial impact of the new information technology. The choices people make about ICT technologies capture the potential immensity of social and spatial changes, which can be so huge that Wilson and Corey (2000) have termed information tectonics. Electronic space has emerged in the electronic age, with the need to plan cyber structure and its relationship to social forces. Cyber city entails planning designs and policy choices, where public or private spaces become blurred and may need to be redefined in “web cities” (Aurigi 2005). The best example for an Asian country to plan its future and cities is Malaysia. That country has planned to build its future on an explicit reliance on technological innovations. Malaysia's Vision 2020 is essentially built upon its technological uplift and reaching developed status via ICT policies and investments. The focus is in the new Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) from the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport, with the administrative capital of Putrajaya and the science park of Cyberjaya in between 41 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 (Bunnell 2004, pp. 351–376). Similarly, Singapore has envisaged its future through ONE, that is one network for everyone, in which internal spatial organization and ICT infrastructure are integrated through technology corridors (Wilson and Corey 2000). The Malaysian and Singapore examples represent a genre of intelligent cities which can inspire other Asian cities about their future. Reflections on Asian cities and urbanization Earlier in this paper in Table 2, it is shown that Asia as a whole reached a level of urbanization only of 39.7% in 2005, albeit the existence of sizeable sub-regional variation. In 2007, however, for the first time in human history more people lived in urban settlements in the world, making the twenty-first century the urban century. The implications for future urbanization in Asia are immense. It means, first and foremost, there is considerable room for Asia to urbanize in order to “catch up” with the world average. It will still be a long distance to the urbanization level of 70% or more in developed countries. Indeed, the United Nations estimates that the world's urban population will further increase by 3.2 billion people by 2050 from now. It is further estimated that some 60% of this increase, or 1.9 billion people, will be in Asia (Montgomery et al. 2003, pp. 11–17, Dhakal 2008, p. 7). Of all the Asian countries, China is the only one that has an urbanization policy of increasing its level of population by about 1% per year to 2050 when its urban population will reach 70% or thereabout (China Mayors Association 2003, p. 39, Yeung 2007a). China's is a policy of deliberate urbanization that began with a low base in 1978, when the country opened up, and that would be most challenging for any country to put into practice. In 2008, China's level of urbanization reached approximately 45.7%, with 607 million urban dwellers (Chen 2009). In an increasingly globalized economy that characterizes most countries in the world, cities continue to play key roles, in particular world cities and global cities. Cities are more than concentration of people and resources. They are hubs of trade, culture, information and industry. They articulate and mediate major functions of the global economy. In Asia, its world cities and global cities have a fair share of their global reach and importance and, if the size of population of cities is taken into consideration as well, Asia would fare even better (Yeung 1996b, 1997b). United Nations source shows that 10 of the 19 largest cities in the 42 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 world in 2007 were located in Asia, and 5 alone were in the sub-region of South Asia (UN DESA 2008, p. 10). Management of these super large cities is, to say the least, extremely challenging (Laquian 2005), especially in infrastructure provision (Laquian et al. 2007). Managing the orderly transfer of rural population to urban areas has always been a thorny problem for many governments to tackle. Sustained and high rates of economic growth in China and India over the two decades have raised the prospect of a recentralization of global economic growth to Asia in which their cities will be major propelling agents. The historical pattern of economic growth in India is most revealing. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8% of the world's economic output, whereas India was producing 22.5% (Dalrymple 2007). This set of figures, as well as other similar data, unravels the trajectory of global economic growth which, prior to the advent of the Industrial Revolution, was heavily centred in India and China. In addition, Table 4 shows their relative global shares in economic output and population in the twentieth century. In their share of world economic output, both China and India exhibit a pattern of a sharp drop in 1950, reflecting the effects of World War II. However, at century end their relative importance was back to, indeed exceeded, where they were before in 1913. Both China and India had a smaller relative share of world population by century end than the beginning of the century, more markedly in China because of a successful one-child policy adopted since the late 1970s. The record of recent economic growth and reforms in China and India has encouraged many observers to think that the world is perhaps entering another transition with them playing more enhanced global roles (Faber 2002, Tseng and Cowen 2005). Will the recent global economic crisis present opportunities for another turning point? To generate new global demand to sustain the next phase of growth, it is almost a consensus that this will not come from the United States, Europe and Japan, which still account for more than half of the global economy. Some would even argue that China, almost alone, has the means to lead the global economy out of its doldrums, with India and other Asian countries playing supplementary roles (Moeller 2009). Beyond Asia, there are other countries in the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) grouping, forming a powerful cluster with their large and rapidly growing economies and possible forces for rebalancing global demand. Friedmann (2005) in a recent book has provocatively submitted that the 43 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 world is flat. Flatness in this sense means more countries are becoming good places to do business – more stable, open and market-oriented. Many Asian cities, especially those along the Pacific coastal region, have truly embraced this concept and have adopted placemaking policies, with global networking as one of their objectives. Asian cities are increasingly conscious of their economic competitiveness and business environment and have fared well in global rankings, notably Hong Kong and Singapore (Yeung 1987, 2001c, 2004b, Ni et al. 2009). If indeed global economic growth will gravitate more towards Asia in the future, what rethinking is appropriate for Asian cities to shoulder their newfound opportunities and responsibilities? Firstly, this means that Asian cities will have to cope with growing populations. Energy consumption at current rates is unsustainable in the long run for many Asian cities. Energy consumption has gone largely to buildings, as exemplified by Seoul (57%), Singapore (54%) and Tokyo (53%); to transport, as in Hong Kong (58%); and to industry, as in Shanghai (80%), Beijing (62%) and Kolkata (56 %) (UN-HABITAT, 2009, p. 122). The search for alternative and recyclable energies has to be intensified, in view of the limited stock of fossil fuels and the growing concern of climate change. This brings to a dilemma of whether to build more roads or subways in large cities, especially in China, although the choice is clearly not one or the other. Secondly, where Asian cities have to articulate with the global economy and have disproportionate access to non-integrated hard and soft infrastructure, they have become ad hoc urban amalgams, spanning multiple political jurisdictions that are often in competition (Oliver 2008, p. 22). Metropolitan governance in the age of globalization is particularly challenging and complex. It calls for inclusive urban planning, with a political commitment to pro-poor development to ameliorate worsening economic and social inequality. Governing a city of cities demands effective leadership, efficient financing and active citizen participation (UN-HABITAT 2009). Finally, haste brings environmental ruin, corruption and other negative side effects in the rush to mount urban infrastructure projects. More than 40 cities in China are in a frenzy to build subways, which total 1,700 km of new urban metro rail expected for completion in 2015 at a cost of 623 billion yuan or US $90.74 billion. The hectic pace of construction has resulted in an alarmingly high accident rate, with deaths, building collapses and economic costs (Toh 2009a) In addition, China's much-vaunted 4 trillion yuan (US $582.1 billion) stimulus package being implemented in 2009 has led to fears of wasted resources and misallocated funds due to 44 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 shoddy construction and environmental damage (Toh 2009b). In sum, Asian cities have to reflect on where they have fallen short in their current practices and policies and in what directions they should seek changes, innovations and breakthroughs to meet the new urban challenge. READING MATERIAL NO. 5 Asian Solutions to Asia’s Urban Challenges by Anthea Mulakala and Minjae Lee https://asiafoundation.org/2017/06/14/asian-solutions-asias-urban-challenges/ According to UN Habitat’s most recent World Cities Report, cities today make up more than half of the world’s population, emit 70 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, and account for 80 percent of global GDP. These figures underscore the fact that rapid urbanization is one the most critical trends shaping the world today. And nowhere will the impact of our collective successes and failures managing our cities be greater than in Asia. The World Bank estimates that since 2000, over 200 million people have migrated into cities across Asia, but despite this rapid migration, approximately half of the continent’s population still live in rural areas. This means that Asia’s cities can expect an even more rapid influx of migrants in the decades to come, which will drive much of the economic growth, but also put greater strain on the region’s resources. In May, urban development experts, city government officials, and scholars from across Asia gathered in Manila for the 16th meeting of the Asian Approaches to Development Cooperation (AADC) dialogue. (Read more about this ongoing series here). The conference explored planned urbanization and the New Urban Agenda (NUA), and how Asian countries are helping each other through South-South cooperation and innovative partnerships to tackle urbanization challenges and achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11: making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Over the course of the conference, participants from 10 countries shared best practices in how their cities and countries are partnering to tackle urbanization. Here are a few highlights: 45 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Singapore shares livable city lessons with Amaravati, India The world’s most famous city-state, Singapore, and its Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) is collaborating with the Andhra Pradesh government to build a new capital city, Amaravati, from scratch. A key feature of the partnership is the focus on sustainable and green infrastructure, including the development of natural waterways, providing green public spaces and efficient public transport. Amaravati will be 10 times the size of Singapore but hopes to emulate Singapore’s reputation as a sustainable and livable city. Safer cities for women, from Delhi to Jakarta and Quezon City Both the SDGs and the NUA recognize universal access to safe and inclusive public space as an essential element of a city. Safetipin, a social enterprise based in India, created a map-based online and mobile phone application that collects and disseminates safetyrelated information through various methods, including crowd-sourcing. Local residents contribute directly to the data collection, which is not only shared to the public, but also reported to local governments. Safetipin started in Delhi, expanded across India and is now operating in Jakarta, Nairobi, Bogota, and Quezon City. Data is also being collected in eight additional cities including Rio de Janeiro, Kuala Lumpur, and Johannesburg. The app is available in English, Hindi, Spanish, Mandarin, and Indonesian. Thailand supports urban infrastructure in the Greater Mekong sub-region Access to sustainable physical infrastructure, such as roads, power, and telecommunications, is another essential element in urban development and planning—but one that requires much financial and technical assistance. Thailand’s Neighboring Countries Economic Development Cooperation Agency (NEDA) has been assisting with trade and investment facilitation, transportation within the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), and more recently, urban development. In Laos, NEDA provided financial assistance for a drainage system and road improvement project in Vientiane Capital City. It was noted that significant changes in the area could be observed after improvements were made. The commercial and residential area expanded and economic activities heightened as a result of the alleviated traffic and flood conditions. Technical assistance was given to Yangon, Myanmar, to conduct a feasibility study and design a power system that can keep up with the rapid economic growth in Yangon. Additionally, projects to improve GMS interconnectivity have been successful in developing subregional roads, power, and telecommunication linkages. 46 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 NGO partnership tackles Ulaanbaatar’s urban sprawl The growth of unplanned, peri-urban settlements, or ger areas which account for more than half of the residents of Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, has presented a growing urbanization challenge for the country, as many residents lack access to water, sanitation, or central heating. In 2013, The Asia Foundation forged a partnership between Solo city in Indonesia, and local NGO Solo Kota Kita (SKK), to conduct a community mapping initiative to provide planning tools for Ulaanbaatar officials to better understand and meet the needs of its 700,000 ger residents. With training and support from Solo Kota Kita, the Ulaanbaatar government and local leaders have improved their community planning capacity, mapping the availability and accessibility of basic services in 87 neighborhoods based on 11 indicators and developing a community mapping website where the maps can be accessed by citizens and city officials as an advocacy and planning tool. The City Municipality has subsequently expanded the community mapping to the cover the entire city. China-Bangladesh one-stop shop partnership Developing local solutions for the efficient delivery of basic services within urban communities in Asia is a rising challenge. Since 2014, UNDP has facilitated a partnership between China and Bangladesh to improve urban service delivery in Bangladesh. Mayors from several cities in Bangladesh visited Beijing to observe its “one-stop shop” community service centers, which streamline the provision of essential services including birth and death certificates, trade licenses, inheritance, and succession certificates. Following the visit, the mayors returned to Bangladesh and designed a one-stop service center prototype for Bangladesh, building on the Beijing model. The initiative is currently being piloted in Gazipur. These examples demonstrate how Asian development cooperation is driving sustainable urbanization in Asia. Through technical assistance, public-private partnerships, innovative sharing, and problem solving, Asia’s urban challenges are being met by Asian solutions. South-South cooperation will remain instrumental in Asia’s future as it continues to meet urban challenges in the region’s dynamic cities. Anthea Mulakala is The Asia Foundation’s director for international development cooperation. Minjae Lee is a KOICA Young Professional based in the Foundation’s Korea office. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and not those of 47 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 The Asia Foundation or its funders. YOUR PROJECT After analyzing the reading resources available to this module, you will create a critical analysis about the continuous urban development in the country. Please consider the set of instructions and expectations in creating your final paper. If you follow the instruction very carefully and have completed all the three tasks that were given, a hundred points will be given to you. OUTPUT CONDITION: Take note of the guidelines to follow as you complete your written output. 1. The paper must contain an introduction, definition of terms, literature review, body, conclusion, and references as its parts. 2. Written analysis should be a maximum of five hundred (500) words. Total number of words should be indicated on the last page of your output. 3. use the format (a) short bond paper, (b) fontstyle is Century Gothic, (c) font size is 12, (d) double spacing, and (e) justified. 4. The file must be submitted with the filename SURNAME_FIRSTNAME_SUBJEC T_DATE SUBMITTED. RUBRIC OF ASSESSMENT: Take time to review the rubric of evaluation which inform you of the how your OUTPUT would be graded CRITERIA Accuracy Content Cites information that is accurate and with precise and logical details. Focuses on the main topic and cites relative information that adheres to the content. Creativity POINTS 30 30 20 Emphasizes the aesthetic side of knowledge which engages the readers to explore the study. Grammar Format Uses correct grammar that makes the paper more comprehensible and coherent. Follows the general format in writing the paper which makes the study organized and systematic. 10 10 48 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 TOTAL: 100 points YOUR POINTS AND NOTES (to be accomplished by the teacher) ANSWER SHEET: Place the content of your answers to the activity here. 49 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 READING MATERIAL NO. 6 Challenges and Opportunities for Urban Development in the Philippines By Samantha Deave https://asiahouse.org/news-and-views/challenges-opportunities-urban-development-philipp ines/ https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/unlocking-the-philippines-urbanization-potential “For Asia 2025, an Asia House publication launched on March 8, the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Ayala Corporation Jaime Augusto Zóbel de Ayala plh contributed his thoughts on the challenges and opportunities for urban development in the Philippines.” Urbanisation has been a significant phenomenon globally, and has potentially been a key contributor to progressive development. Over the last half-century, the world has become increasingly urbanized. In East Asia, over 50 percent of people live in cities and, today, the whole of Asia is home to more than half of the world’s megacities. This trend is expected to continue, with 75 percent of today’s world population projected to be living in urban areas in the next 35 years. This is an exponential increase from the 1950s when the total population was only 2.5 billion. The Philippine experience sees nearly half of the population residing in urban centres, with almost 25 per cent in the capital alone. Massive urban sprawl across the south and east ends has expanded the metropolis into the Greater Manila Area. This expanded metropolitan area has a population of about 25 million, or a quarter of the country’s total population. Over the past two decades, regions within and adjacent to Metro Manila have sporadically grown without proper planning, with their capacities unable to keep up with a growing urban population. This has led to a host of infrastructure, health, environmental and social problems, including traffic congestion, burgeoning informal settlements, disaster vulnerability, and threats to water and food security. A JICA study1 cited how traffic congestion currently robs Filipinos of up to US$55 million a day. The study further noted that, if no intervention takes place, this amount is projected to increase to over US$130 million a day. Clearly, much needs to be done in infrastructure development. Based on the World Bank’s estimates, the Philippines would need to hit spending levels of at least 5 per cent of GDP in 50 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 infrastructure projects to catch up with its Southeast Asian neighbours. Our average infrastructure expenditure since 2009 has only been 2.2 per cent of GDP. Risks and opportunities Cities are the main centres of consumption, resource use, congestion, and waste. Eleven of the 20 most polluted cities, and 15 of the 20 most vulnerable cities to rising sea levels, are in Asia. Despite all these problems, cities are the growth drivers of most economies, particularly when one looks at clusters of cities. Urban density can actually be a positive contributor on many fronts. It is usually accompanied by lower poverty incidence, increased productivity, and steeper economic growth. This is true across the board, and even more so as the city size grows. The high concentration of industries and services in highly urbanised cities has attracted job-seekers to relocate in droves to find employment and gain better access to education, healthcare and overall quality of life. Urban density creates critical mass, attracts diversity, and makes possible the ‘creative combustion’ that brings life, new ideas, entrepreneurial vigour, and an innovative verve to urban communities. Today, when people think of places to live, work, invest, or visit, they think not so much of countries; they think of cities. Decisive interventions are imperative at the city level However, it is important to manage the ‘quality of that density’. Cities like Metro Manila need to ensure that urban growth is supported by adequate infrastructure, such as adequate power, water, roads, transport systems, flood control, and waste management, to name a few. In response, private sector groups, such as the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC), have been pushing for the trend towards sustainable, competitive, and liveable cities. ABAC is of the belief that cities can achieve resilience if they will elevate their competitiveness level in key indicators, such as transportation and infrastructure, technology readiness, health and safety, environment, and ease of doing business. This initiative can be a potentially viable 51 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 long-term solution to mitigating the impact of climate change. However, more work clearly needs to be done and cooperation and synergies between the public and private sectors will be integral to taking this initiative forward. Aside from hard infrastructure, we need to ensure that the right level of governance, urban management and planning is in place to support Metro Manila. I believe there is a need for the creation of a central institution that would spearhead a cohesive and strategic planning and execution of a national urban agenda – from land use and urban planning to infrastructure development while ensuring the sustainability and resilience of the cities. While the local government units continue to do their part in addressing the challenges, the lack of an integrated urban management framework and execution falls short in enabling seamless connectivity across the whole spectrum. Greater private sector participation in urban development Since a developing country such as the Philippines would have significant constraints investing in capital assets for infrastructure, public services, and even disaster management, the government has increasingly involved the private sector in providing these services to address these challenges without straining public finances or burdening the population with higher taxes. The private sector, for its part, has, over time, made significant strides in helping to augment the Philippines’ urbanisation challenges, particularly in the areas of transport, communication, property development, and disaster management. Much more needs to be done and I believe the private sector can still intensify its role in helping to develop more liveable communities within and outside the metropolis that encourages decongestion and improves the standard of living significantly. At Ayala, for instance, we have been pushing to improve our existing townships into more sustainable developments and building new integrated mixed-use projects of different scales, both within and outside Metro Manila. To date, we have over 8,000 hectares of strategic land bank, out of which we have 16 large-scale, mixed-use developments across the Philippines. In each of the cities that we have presence in, we work hand in hand with 52 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 the local government in planning and building key infrastructure requirements around our developments, including access roads, pedestrian walkways, and water distribution. Another example is how the build-operate-transfer law enacted in the 1990s has paved the way for private sector participation in sectors critical to economic growth, particularly in power generation, telecommunications, transport infrastructure, and water utilities. Ayala has been an active participant in some of the Philippines’ landmark Public-Private Partnership (PPP) initiatives. In 1997, Ayala won the country’s first PPP programme, which was water privatization for the east zone of Metro Manila. Over the last 18 years, Manila Water has greatly improved water distribution in the east zone, driving down non-revenue water to 11 per cent and bringing water to 99 per cent of the households in the area. Today, Manila Water is a leader in the water sector, not only in Manila, but in other parts of the country, as well as in Southeast Asia. Similarly, we took part in the government’s liberalization efforts of the telecommunications sector also in the 1990s and established Globe Telecom. From a virtual monopoly back then, the telecommunications industry today has spawned a host of entrepreneurial activity and ‘cottage industries’ in various mobile content and services. More importantly, the vast improvement in the telecommunications infrastructure has given rise to the business process outsourcing industry, currently one of the main growth engines of the country. More recently, the government has started a PPP programme that includes several potentially impactful transport infrastructure projects in rail, toll roads, and airports. This should create an ecosystem that is conducive for urban success. From what we have seen in the Philippines, good public governance is crucial for implementing successful PPPs. Multiple stakeholder participation and access to information for informed dialogues are important, starting from the planning process to the implementation. Since the auctions under the PPP framework are conducted in a considerably fair and transparent manner, the projects have attracted great interest from both local and foreign investors, including the Ayala Group. 53 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Broadening access to serve communities It is also worth noting how business groups in the Philippines are increasingly broadening access to products and services that touch on basic needs to a much larger segment of society. In addressing our urbanisation challenges, it is essential that we aim for progress that is felt across all segments of the population. From our own personal experience at the Ayala group, we have, over time sought ways to provide products and services that meet a broader set of needs, at varying price points. We believe our businesses can play a role, in some measure, in providing practical and realistic solutions to address some of the challenges confronting the broader society given that we participate in industries that touch on basic human needs – housing, banking, telecommunications, water distribution, and, more recently education. These are just a few examples of what we call ‘shared value’. Overall, we have seen that these initiatives can create social inclusivity while yielding attractive returns, and creates a more holistic developmental approach to communities and to addressing challenges of growth and urbanisation. This has driven us as a group of companies to seek creative and innovative ways to broaden access to our products and services with a view towards meeting the needs of a large segment of unserved communities, particularly those at the base of the economic pyramid. Supporting the implementation of this core value is our group-wide sustainability policy. This covers operations, products and services, the supply chain, our human resource practices, community involvement, and our overall management approach. We have started benchmarking the Ayala Group against global sustainability indices and best practices, and we have implemented a comprehensive 360 degree framework to monitor key sustainability indicators and metrics that we focus on. Conclusion In summary, the sustained economic growth and urban sprawl have resulted in overcapacity in infrastructure and increased vulnerability to disasters. However, population density per se is not the problem. In addition to hard infrastructure, we need to ensure that the right level of governance, urban management and planning is in place to support 54 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 Metro Manila. I believe there is need for the creation of a central institution that would spearhead a cohesive and strategic planning and execution of a national urban agenda, where clear accountabilities are defined. Second, there is a growing importance for government and private sector collaboration to address some of the key urbanisation challenges, particularly in critical sectors such as infrastructure and shared value creation. As a final note, as this unprecedented positive environment taking place in the Philippine economy is poised to continue in the next few years, it is imperative that we act together to intensify our efforts to address the rapid urbanisation. I believe that to a large extent, this entails collaborative efforts across multiple sectors – the government, the private sector, the civil society, and multilaterals. This, combined with a healthy sharing of expertise and best practice among peers, can well fortify our efforts in dealing with urbanisation challenges. READING MATERIAL NO. 7 Emerging Cities in the Philippines are on the Rise Despite Economic Challenge By Leony Garcia https://businessmirror.com.ph/2018/10/29/emerging-cities-in-the-philippines-are-on-the-rise despite-economic -challenge/#:~:text=THE%20ten%20%E2%80%9Cnew%20emerging%E2%80%9D%20cities,Tug uegarao%20City%2 C%20and%20Zamboanga%20City. VARIABLES such as topography, climate, tax code, and cost of living —in addition to proximity to family and friends—all play roles in the emergence of cities and attractive places to live in. The factors that make some parts of the country preferable to others as a place to live and raise a family vary from one person to the next. Still, some cities are demonstrably more attractive to new residents than others; thus the reason for population growth. Population change is the product of two factors–net migration and natural growth. Natural growth is simply the number of births over a given period less the number of deaths. Net migration is the difference between the number of new residents—either from other parts of the country or from abroad—and the number of residents who have left the area. 55 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 As of 2017, there are 47 megacities in existence. Most of these urban agglomerations are in China and other countries of Asia. The largest are the metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Shanghai, and Jakarta, each having over 30 million inhabitants. China alone has 15 megacities, and India has six. Other countries with megacities include the United States, Brazil and Pakistan, each with two. In the 2018’s Global Cities Index and Emerging Cities Outlook (A.T. Kearney), seven new cities have been added to the Index and the Outlook: In the US, Seattle joins the rankings for the first time, and in China, six cities have emerged in the rankings (Changsha, Foshan, Ningbo, Tangshan, Wuxi, and Yantai). The list identifies the top emerging cities by measuring human capital, business activity, information exchange, cultural experience, and political engagement. China’s key cities have experienced greater progress than cities in the other regions of the world during the 10 years of A.T. Kearney’s Global Cities research: business activity remains the dominant factor, but human capital and cultural experience are also significant drivers of growth. Established in 2008, A.T. Kearney’s Global Cities was one of the first to rank cities based on their global standing, and it remains highly regarded for its holistic assessment of city capabilities and potential. Designed by top academics and business advisors, the analysis is based on facts and publicly available data. The report is developed annually, updating the underlying information and reviewing whether new cities meet the criteria for inclusion. Since its inception, the report added the Global Cities Outlook and it increases the number of cities it assesses nearly every year. What makes an emerging city? ACCORDING to experts, a city may be considered “emerging” if there is potential for job creation, a healthy workforce, and efficient land use; in addition to visionary leadership, political will, good planning, good design, and good governance. Gateway cities such as those with international airports and seaports also have an edge over others in terms of trade and tourism opportunities. 56 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 By these standards, the top emerging cities outside of Metro Manila are Puerto Princesa, Zamboanga, Clark, San Fernando (Pampanga), Laoag, Vigan, Legazpi, Balanga, Batangas, Lucena, and Iloilo. Davao and Cebu have already far exceeded the pack and ae almost in the same cluster as Metro Manila.Not following the mistakes of Manila, the Davao and Cebu magalopoli should pursue better mobility through walkable and bikable streets with well-connected mass transport systems. Over the years, there’s a lot of development potentials for Zamboanga City. Dubai, like Zamboanga is a port city. But unlike Dubai, Zamboanga is blessed with more natural resources. Zamboanga Peninsula plays a critical role in realizing the medium and long-term goals of Mindanao and BIMP-EAGA which is to become a major location in Asean for highvalue-added agro-industry, natural resource-based manufacturing, and high-end tourism that will eventually shift towards ensuring socio-economic, physical development, and a southern gateway to and from the Philippines. Laoag, on the other hand, is posing to be the international gateway between the Philippines and the wealthier countries of North East Asia. Currently, the Laoag International Airport has direct flights to and from Guangzhou, China. Learning from ‘instant’ cities of the world. These are cities that became First-World caliber in less than 15 years: San Francisco, Zurich, Singapore, and Hong Kong. These cities were able to transform from one resource to another. Zurich, for instance, was able to move forward from chocolate and watch-making to becoming Europe’s leading international financial center. After the gold rush, San Francisco, on the other hand, shifted from a mining town into a financial, tourism, and technology hub. While Dubai transformed from an oil-dependent city to one that was driven by tourism, trade and commerce, real estate, health, and education. “Our cities should be in a continuous state of improvement. We should not be complacent with just one source of revenue. For instance, real estate and business process outsourcing may be booming today. But what are we doing now to ensure that we will have other sources of income in the event that these two industries slow down? We should be able to improve our competitiveness in tourism, agriculture, finance, education, and health care, among others.” This is according to Architect Felino A. Palafox, Jr., in a report written in April 2017. “Growth is inevitable, growth is necessary. In setting the framework for the development of our cities, we must focus on practices that are environmentally sound, 57 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 economically vital, and that encourages livable communities—in other words, smart growth and new urbanism. Some of the best practices elsewhere in the world can be appropriately applied to address the country’s urban issues and challenges to make Philippines more livable and globally competitive,” he concluded. New Emerging Cities THE ten “new emerging” cities in the Philippines are recognized for their potential to become next wave cities. These new are, in alphabetical order:Balanga City, Batangas City, Iriga City, Laoag City, Legazpi City, Puerto Princesa City, Roxas City, Tarlac City, Tuguegarao City, and Zamboanga City. Meanwhile, the country’s $14 billion ‘pollution-free’ city, the New Clark, is expected to be larger than Manhattan. In a 2016 survey, navigation company Waze ranked Manila as having the “worst traffic on Earth.” The city’s reliance on cars also exacerbates its growing air-pollution problem.As a possible solution to Manila’s smog and gridlock, on the works is an entirely new, more sustainable city called New Clark City. The New Clark, about 75 miles outside Manila, calls for drones, driverless cars, technologies that will reduce buildings’ water and energy usage, a giant sports complex, and plenty of green space. According to the development plan, the city will eventually stretch 36 square miles — a land area larger than Manhattan — and house up to 2 million people. Developers say the urban plan will prioritize environmental sustainability and climate resilience. With a minimum elevation of 184 feet above sea level, the city will likely not see much flooding. To reduce carbon emissions, two-thirds of New Clark will be reserved for farmland, parks, and other green space.The buildings will incorporate technologies that reduce energy and water usage.Driverless cars, running on electric energy rather than CO2emitting gas, will roam the streets.Additionally, the city will feature a giant sports stadium and an agro-industrial park. New Clark’s developers, BCDA Group and SurbanaJurong, see the first phase of the project finished by 2022 butthe goal is to keep developing as technologies advance. 58 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|26771016 The vision for New Clark certainly sounds utopian.But the ambitious plan faces several challenges, including persuading Manila residents to move there. New infrastructure projects, meanwhile, could bridge the distance between Manila and New Clark City, Wong said. A brand new railway line is being built by the Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport & Urban Development. The train would reduce the travel time between the two cities to one hour from the current two to three hours. In late May, BCDA started the bidding process for companies to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain power and water systems in New Clark City. The project is mainly funded through public-private partnerships — and has been earmarked among the Build, Build, Build (BBB) projects of the current government. The project is planned to be smart, sustainable and resilient to disasters, according to SurbanaJurong CEO Heang Fine Wong. The new urban space would become a “twin city” to Manila. The Philippine government already announced it is committed to moving some offices to New Clark City, but the main goal plan is for foreign investors to set up operations there, according to Wong. But technical hurdles would still need to be resolved said Wong. “You need that network of communication. And also a cyber security network needs to be put in place,” he said. 59 Downloaded by Czar Jade Galvez (caregalvez@gmail.com)