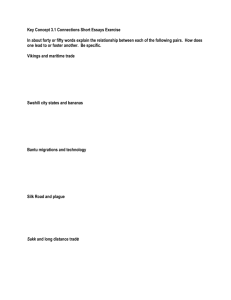

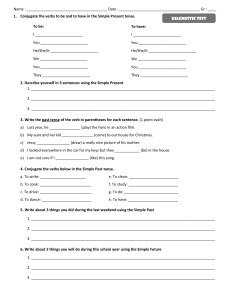

Swahili Grammar Textbook: Introductory & Intermediate Levels

advertisement