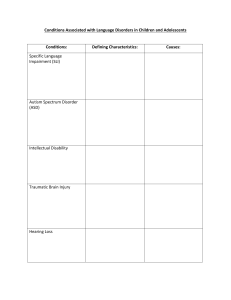

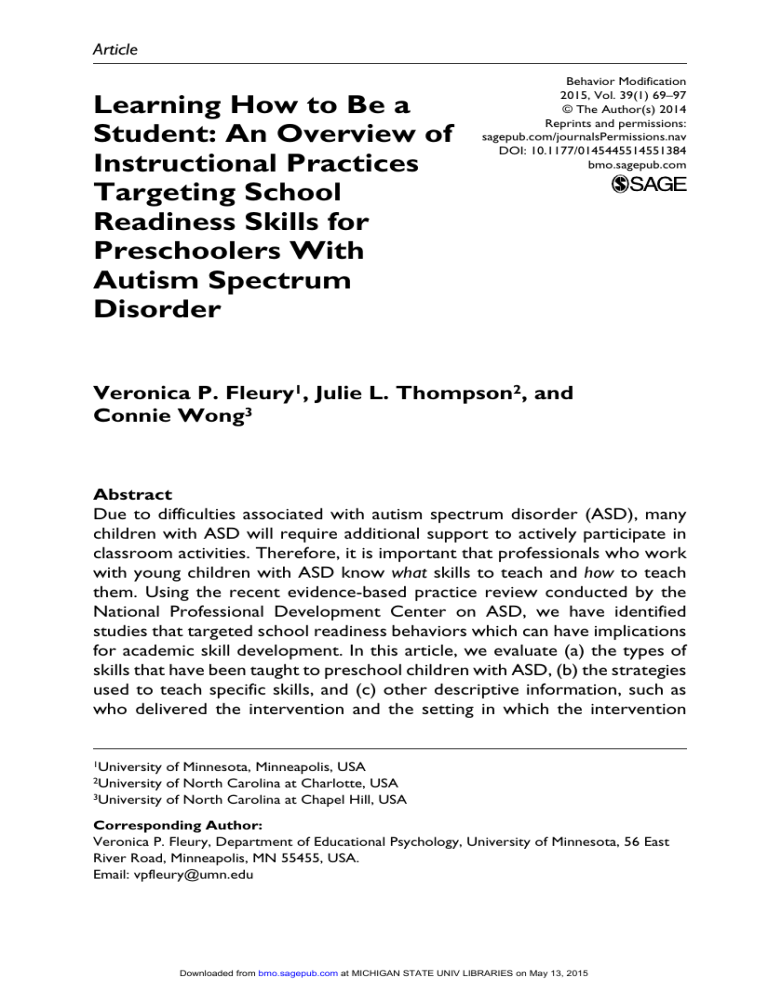

551384 research-article2014 BMOXXX10.1177/0145445514551384Behavior ModificationFleury et al. Article Learning How to Be a Student: An Overview of Instructional Practices Targeting School Readiness Skills for Preschoolers With Autism Spectrum Disorder Behavior Modification 2015, Vol. 39(1) 69­–97 © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0145445514551384 bmo.sagepub.com Veronica P. Fleury1, Julie L. Thompson2, and Connie Wong3 Abstract Due to difficulties associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), many children with ASD will require additional support to actively participate in classroom activities. Therefore, it is important that professionals who work with young children with ASD know what skills to teach and how to teach them. Using the recent evidence-based practice review conducted by the National Professional Development Center on ASD, we have identified studies that targeted school readiness behaviors which can have implications for academic skill development. In this article, we evaluate (a) the types of skills that have been taught to preschool children with ASD, (b) the strategies used to teach specific skills, and (c) other descriptive information, such as who delivered the intervention and the setting in which the intervention 1University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA 2University of North Carolina at Charlotte, USA 3University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA Corresponding Author: Veronica P. Fleury, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota, 56 East River Road, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA. Email: vpfleury@umn.edu Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 70 Behavior Modification 39(1) took place. We conclude by offering suggestions for future research and considerations for professional development. Keywords autism spectrum disorder, school readiness, evidence-based practice, preschool Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in general education settings has proven to be a significant challenge despite legal mandates (Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 2004; Kieron, 2013; Koegel, Matos-Freden, Lang, & Koegel, 2012). Only 58% of children with ASD spend more than 40% of their day in general education settings compared with 82% of children from all other disability categories (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs, 2013). This statistic implies that a disproportionate number of children with ASD are educated in more restrictive environments, perhaps due to the complex needs of children with ASD that result from deficits in social communication and social interaction, and restrictive, repetitive patterns of behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In school settings, children with ASD demonstrate significantly higher behavioral excesses such as aggression or self-injurious behavior and deficits including limited communication and difficulty participating in school routines (Ashburner, Ziviani, & Rodger, 2010). These behaviors may lead to placement in more restrictive settings (Machalicek, O’Reilly, Beretvas, Sigafoos, & Lancioni, 2007; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996). The trajectory of special education has moved beyond mere access to free appropriate public education to a greater emphasis on educational achievement for all individuals with disabilities (Kieron, 2013; Koegel et al., 2012). It is important for children with ASD to have full access to the general curriculum content for their assigned grade level regardless of whether they are served primarily in self-contained or inclusive settings. Accordingly, we need to have a better understanding about the foundational skills that will enable children with ASD to appropriately participate in classroom activities, thereby improving their opportunities to access the general education curriculum. School Readiness for Children With ASD The National Governors Association (NGA; 2005) Task Force on School Readiness described children’s school readiness as manifested in five areas: Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 71 Fleury et al. health and motor skill development (e.g., vision, hearing, gross and fine motor skills), socio-emotional development (e.g., self-regulation, establishing reciprocal relationships with peers and adults), motivation to learn (e.g., persistence, sustained attention to educational tasks), language and early literacy skills (e.g., listening and story comprehension, phonemic awareness, print concepts), and conceptual knowledge and application (e.g., vocabulary, reasoning, associations, problem solving). All of these domains are important to building a foundation for learning. Characteristics of ASD (e.g., social communication deficits, restricted interests) may place children with ASD at a distinct disadvantage for naturally developing some facets of school readiness skills. The Pre-Elementary Longitudinal Study (PEELS) is a national study that addressed four key areas of school readiness—emergent literacy, early math proficiency, motor performance, and social behavior—in preschool children with special needs (National Center for Special Education Research, 2006). Data for children with ASD show an uneven profile in school readiness behavior. As a group, children with ASD performed above the population mean on their ability to identify letters and words and were within normal limits in receptive vocabulary, quantitative concepts, and motor skills measures. As expected, the greatest skill deficit for children with ASD was in the domain of social behavior. Children with ASD performed two standard deviations below the population mean on the social skills subscale of the Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales (PKBS-2). This subscale is used to assess personal behaviors such as “works or plays independently,” “follows rules,” “accepts decisions made by adults,” and interpersonal skills such as cooperation, turn-taking, and comforting other children. Furthermore, children with ASD scored significantly higher than the norm on the PKBS-2 problem behavior subscale. Higher scores on this scale indicate greater concern about problem behavior and include items such as “defies teacher or caregiver,” “takes things away from other children,” “is restless or fidgety.” Children with ASD also had difficulty on measures of independence, self-control, and personal responsibility (Adaptive Behavior Assessment Scale, ABAS-II) which includes items such as “follows adults request to quiet down and behave,” and “works independently and asks for help only when necessary.” In fact, children with ASD had the poorest performance on the PKBS-2 problem behavior subscale and the ABAS-II self-direction scale compared with all other disability groups. These early deficits in school readiness, primarily in the social behavior domain, can have implications for future academic success for children with ASD. Lloyd, Irwin, and Hertzman (2009) conducted a longitudinal study that compared kindergarten school readiness scores with fourth-grade assessment outcomes for individuals with disabilities, including 175 children with ASD. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 72 Behavior Modification 39(1) These researchers found that 88% of the children with ASD did not demonstrate school readiness when assessed in kindergarten and approximately 86% of children with ASD “did not meet expectations” in mathematics and literacy following fourth-grade assessments. These results provide evidence of a correlation between school readiness behavior and later school outcomes for children with ASD. If we expect children with ASD to be able to access and benefit from the general education curriculum, professionals who work with young children with ASD will need to identify what skills to teach and how to teach them. A number of reports have been published that provide a broad overview of focused instructional practices (National Autism Center, 2009; Wong et al., 2014) and comprehensive treatment models (Dawson et al., 2010; Rogers & Vismara, 2008; Strain & Bovey, 2011) that are supported by research to improve developmental outcomes for children with ASD. The National Professional Development Center (NPDC) on ASD recently published an updated report of evidence-based practices for children, youth, and adults with ASD. The NPDC report represents the work of a large systematic review of focused intervention strategies for individuals with ASD that were published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and 2011. Content analysis of these studies yielded 27 evidence-based practices that encompass a variety of outcomes, including those that have been found to be effective in improving pre-academic/academic skills and school readiness skills for individuals as young as toddlers. In this report, the authors differentiated between studies that improved pre-academic and academic skills from those that address school readiness skills. The NPDC work group defined pre-academic/academic skills as outcomes broadly related to performance on tasks typically taught and used in school settings, whereas school readiness was defined as outcomes that are related to task performance but are not directly related to task content. Accordingly, studies that targeted skills such as matching, sorting, reading, and letter identification were classified as pre-academic/academic skills whereas engaging in tasks, orienting to materials, remaining in seat or activity area, and responding to instruction were considered school readiness skills. In addition to knowing what skills to teach and how to teach them, it is also important to identify where these studies are conducted and who delivered the intervention to facilitate the translation of research to practice. Historically, most studies have been implemented in clinical settings and/or with highly trained behavior analysts (Kasari & Smith, 2013). Although this may be helpful in identifying potentially effective strategies, it does not guarantee that classroom teachers and families will readily accept or be able to implement these strategies in their classrooms or homes. To ensure strategies Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 73 Fleury et al. can become sustained practices which are practically implemented, it is important to identify feasible and generalizable instructional strategies that can be readily implemented in the public school setting where the majority of children with ASD are educated (Kasari & Smith, 2013). As a result, it is important to identify the interventionist and setting of implementation to guide judgments regarding optimal strategies to support school readiness. Focus of the Present Review To date, a systematic literature review has not been conducted to gain broader insights into preparing young children with ASD to be school ready and equip professionals to effectively teach school readiness skills. The purpose of this study is to review the school readiness literature to evaluate (a) the types of skills that have been taught to preschool children with ASD, (b) the strategies used to teach specific skills, and (c) other descriptive information, such as who delivered the intervention and the setting in which the intervention took place. We anticipate that this information will both highlight areas in need of further study for researchers and also serve as a valuable resource to practitioners who wish to include evidence-based practices as the basis of educational programming. Method Selection Criteria We identified articles to include in our review through the NPDC report, “Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder” (Wong et al., 2014). The NPDC report lists article citations according to the specific evidence-based practices (EBP) they support. Although there is general information about the overall number of studies that were published for each target outcome, specific articles were not organized by outcome categories. For this study, we used the NPDC database of articles to identify 67 studies that targeted school readiness as an outcome measure. We classified preschoolers by their age at the time of study. After screening the participants section of each article, we found 26 studies that included at least 1 child with ASD who was preschool age (between the ages of 3 years 0 months and 5 years 11 months). We excluded one study in this review because the intervention solely targeted the reduction of challenging behaviors, and did not address corresponding improvement on any school readiness behavior. In this article, we focus our review on the 25 intervention studies (21 single-case design; 4 group design) that documented improvement in school readiness skills for preschoolers. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 74 Behavior Modification 39(1) Coding Procedures The reviewers who contributed to the NPDC report participated in a rigorous training to evaluate studies for methodological rigor using criteria that were developed specifically for the project. NPDC reviewers also coded descriptive features for each study that they determined to be methodologically acceptable. Specifically, reviewers coded information about study participants (diagnosis, co-occurring conditions, age), intervention strategies used by researchers (see the appendix), and dependent variables (name, description) measured in each study. Finally, reviewers selected outcome categories that best described child outcomes in each study from 12 outcome categories including social, communication, challenging/interfering behaviors, joint attention, play, cognitive, school readiness skills, pre-academic/academic, motor, adaptive/self-help, vocational, and mental health (refer to Wong et al., 2014 for more detail about reviewer training, article inclusion criteria, and coding procedures). We limited our review to those studies that were classified as having a school readiness outcome. Information about intervention strategies (evidence-based practices) and dependent variables were taken directly from the NPDC data set. We did not need to further evaluate the studies for sample, appropriateness of design, or quality of data analysis because all studies included in the NPDC report were already evaluated for methodological rigor. Rather, we evaluated each article on additional variables that were not included in the NPDC review, specifically information pertaining to the setting where intervention procedures took place and who delivered intervention procedures. Setting. The environment in which the study procedures took place was analyzed in terms of the following set of definitions: Classroom. A school setting in which the child is taught alongside their peers. This term encompasses a number of different educational settings, including: general education, special education, inclusive/integrated classrooms, and self-contained classrooms. Special education classrooms that also functioned as 1:1 settings were coded here provided that other peers (with or without disabilities) were present in the environment. Study procedures that take place on the playground during recess were classified here provided that peers were present at the time of the intervention. Specialized setting (1:1 room). An environment in which the child receives instruction in a 1:1 context separate from the classroom, such as therapy rooms, school office, testing rooms, and specialist rooms. These settings have limited environmental distractions, typically without peers present. We also classified any study that took place within a Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 75 Fleury et al. clinical setting here. Home. The setting where the child permanently resides. Study procedures may take place in any room within the child’s residence, such as the living room, kitchen, or therapy room within the home. Interventionist. The person who was primarily responsible for carrying out the intervention procedures was evaluated using the following definitions: Researcher. A member of the research team primarily carries out the intervention procedure. This includes principal investigators, co-principal investigators, research assistants, graduate students, and others who were employed by the research team. School Personnel. An individual with some professional training carries out the intervention procedures as part of their job. The individual was not directly employed by the research group, but may have received stipends for their participation in the research project. This includes special education teachers, general education teachers, paraprofessionals, and other specialists such as speech-language pathologists, occupation therapists, and/or physical therapists. Researchers who claim that “therapists” or “interventionists” conducted the study were also classified in this category. Parent. A child’s caregiver carries out the intervention procedure. Student/ Peers. The child or his or her classmate(s) or peer(s) are taught to carry out the intervention procedures. Setting and intervention variables are not mutually exclusive. We coded all variables that applied for each intervention study. Although many studies were conducted only in one setting by one interventionist type (e.g., a member of the research team who conducted the procedures in a 1:1 therapy room), some studies were carried out across different settings and/or with different interventionists (i.e., Buggey, Hoomes, Sherberger, & Williams, 2011; Kern, Wolery, & Aldridge, 2007; Shogren, Lang, Machalicek, Rispoli, & O’Reilly, 2011). Reliability Information about article inclusion, intervention strategies, and child outcomes were taken directly from the NPDC database and were therefore not included in reliability calculations. Interrater reliability was calculated on 100% of coding variables unique to this review (i.e., setting and interventionist) for 100% of included studies. We calculated reliability using a point-bypoint formula: (agreement/[agreement + disagreement]) × 100. Interrater reliability reached acceptable levels (Horner et al., 2005) for both setting (M = 86%) and interventionist (M = 82%) categories. The first author and the coder reviewed all discrepancies and arrived at a consensus code to be used in final analyses. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 76 Behavior Modification 39(1) Results Evidence-Based Practices A complete list of studies included in this review, along with their corresponding instructional strategies and outcome definitions can be found in Table 1. The NPDC reviewers identified the primary intervention strategy used in each study that was included in the evidence-based practice report. We pulled this information directly from the NPDC database for this review. Our analysis revealed that 18 of the 27 identified evidence-based practices were used by researchers to improve school readiness behaviors in preschoolers. Evidence-based practices used to improve school readiness included antecedent-based intervention, differential reinforcement, exercise, discrete trial teaching, functional behavior assessment, functional communication training, modeling, parent-implemented intervention, prompting, reinforcement, response interruption and redirection, scripting, self-management, technology-aided instruction and intervention, time delay, video modeling, and visual supports. There were three additional intervention practices that were used that did not meet the NPDC criteria for an evidence-based practice: behavioral momentum intervention, touch therapy, and music therapy. Descriptions of instructional strategies used to promote school readiness behavior are provided in the appendix. Child Outcomes School readiness is a broad term that encompasses a number of behaviors. Our analyses revealed that specific child outcome variables differed across studies, but could be organized into three general categories: classroom behavior, social-communication, and challenging behavior. Several studies addressed multiple behaviors that fit into several categories. Thirty-two percent of studies (n = 8) measured changes in classroom behavior. These behaviors relate to children’s ability to appropriately participate in independent tasks within the classroom environment. Examples of classroom behavior include: attending to activities, engagement, correct responding, complying with teacher directions or classroom routines. Second, we categorized a number of child outcomes as improvements in social-communication or social interaction skills (n = 7; 28%). Behaviors in this category support the child’s ability to interact with his or her peers or adults. Examples include reciprocal conversations in play, initiating social interactions, responding to peers’ social invitations, appropriately expressing needs or desires, and inquiries about the environment or classroom schedule. All of the studies had at least Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 77 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 Participant 1: male; age 3 years 6 months; autism Participant 2: male; age 5 years; autism Participant 1: male; age 5 years; Asperger Participant 2: male; age 5 years; Asperger Participant 1: male; age 5; autism Normand and Beaulieu (2011) Tarbox, Ghezzi, and Wilson (2006) Shogren, Lang, Machalicek, Rispoli, and O’Reilly (2011) 14 children (12 boys and 2 girls) with autism, ages 3-6 Participant 1: male; 5 year, 4 month old; autism Participant 1: male; age 3 years 2 months; autism; mild-moderate autism severity; Caucasian Participant 2: male; age 3 years 5 months; autism; mild-moderate autism severity; African American Participant 1: male; age 4 years 4 months; autism; Caucasian; middle class Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Moore and Calvert (2000) Kleeberger and Mirenda (2010) Classroom behavior Houlihan, Jacobson, and Brandon (1994) Kern, Wolery, and Aldridge (2007) Study Reinforcement Reinforcement and self-management Behavior momentuma Technology-aided instruction and intervention Video modeling Musica Behavior momentuma Instructional strategy Table 1. Intervention Studies That Targeted School Readiness Outcomes. (continued) Appropriate classroom behavior: The extent to which the child followed classroom rules (i.e., stay in your space, keep your hands to yourself, and do what the teacher says) Attending: making eye contact with the adult for at least 3 s prior to instruction Imitation: 70 imitative motor actions were included in the study. After the adult model and prompt, participant scored a 0 for no response, 1 for response without imitation, 2 for partial imitation, and 3 for exact imitation Attention to task: looking at the teacher or learning materials Motivation to work on task: children were given the choice to stay working or go play. If children stayed working, it was scored as being motivating Vocabulary: receptive identification of nouns on flashcards Compliance: initiation of an instructed response within 10 s of the instruction Compliance: appropriate response that occurred within 15 s of request delivery Routine: child independently performs the behavior required in each step of the morning greeting routine Child outcome 78 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Call, Pabico, Findley, and Valentino (2011) Participant 1: male; age 5 years; autism Participant 1: male; age 6 years 2 months; autism Participant 2: male; age 5 years 7 months; autism Participant 3: male; age 3 years 9 months; autism Participant 4: male; age 4 years 10 months; autism Classroom behavior and challenging behavior Ahrens, Lerman, Kodak, Participant 1: male; age 6 years; autism Worsdell, and Keegan (2011) Participant 2: male; age 4 years; autism Participant 3: male; age 5 years; autism Participant 4: male; age 4 years; autism West (2008) Study Table 1. (continued) (continued) Vocal stereotypic behavior: any nonfunctional or noncontextual speech vocalization that is not appropriate Appropriate vocalization: independent vocalization that is contextually appropriate Motor stereotypic behavior: hand flapping (rapid movement of the hand back and forth), body rocking (forward and backward movement of the body), clapping (rapid movement of hands hitting together) Compliance: child exhibits the requested vocal or motor response following adult instruction Elopement: frequency of elopement within 10-s intervals (elopement as any part of the body passing the plane of the doorway of the session room) Prompted correct response: participant touched correct picture within 5 s of a prompt Attending behavior: participant looked at comparison stimuli for at least 4 s, or 1 s each Problem behavior: individually defined for each participant Response interruption and redirection Differential reinforcement Independent responses: unprompted correct responses consisted of responses to the task prior to the controlling prompt being provided Child outcome Visual support Instructional strategy 79 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 9 children (7 males and 2 females) ages 3-6 years (Mage = 5.2 years). Seven of the children had a diagnosis of autism, 1 had a diagnosis of intellectual disability, and 1 had a diagnosis of developmental delay Participant 1: male; age 4; autism and severe cognitive delay Participant 2: male; age 4 years 6 months; autism spectrum disorder and severe cognitive delay; moderate autism severity Participant 1: male; age 5 years; autism; Caucasian participant 2: male; age 7 years; autism and other health impairments; Caucasian Oriel, George, Peckus, and Semon (2011) Reichle, Johnson, Monn, and Harris (2010) Rispoli et al. (2011) Participant 1: female; age 4; autism; severe autism severity; Spanish spoken at home Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Lang et al. (2011) Study Table 1. (continued) Antecedent-based intervention Reinforcement Exercise Other–English vs. Spanish instruction in DTT Instructional strategy (continued) Correct responses: correct performance following a teacher’s direction Repetitive behavior: audible click of the tongue during instruction Correct academic response: a child responds correctly to a direction given by the teacher Incorrect academic response: a child responds incorrectly or provides no response to a directive given by the teacher Stereotypic behavior: repetitive behaviors that included hand and arm flapping, body rocking, and toe walking On-task behavior: percentage of time the child is seated and is consistently responding to teacher directives Task engagement: percentage of work units successfully completed Challenging behavior: percentage of work units in which challenging behavior occurred (e.g., pushing materials off the table) Problem behavior: throwing objects (i.e., object launched from hand), inappropriate vocalizations (repeated sound “eeee”) Child outcome 80 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Social communication/social interaction Buggey, Hoomes, Sherberger, Participant 1: female; age 4 years 2 months; and Williams (2011) PDD-NOS; moderate autism severity Participant 2: male; age 4 years 2 months; PDD-NOS; severe autism severity Participant 3: male; age 3 years 10 months; PDD-NOS; severe autism severity Participant 4: female; age 4 years 2 months; PDD-NOS; severe autism severity Ganz, Flores, and Lashley Participant 1: male; age 3 years 6 months; (2011) autism; mild-moderate autism severity Participant 2: male; age 4 years 11 months; autism; mild-moderate autism severity Kaiser, Hancock, and Nietfeld Participant 1: male; age 4 years 6 months; (2000) autism Participant 2: male; age 2 years 11 months; Asperger Participant 3: male; age 3 years 1 month; PDD-NOS Participant 4: male; age 3 years 4 months; autism Participant 5: male; age 4 years 5 months; autism Participant 6: male; age 2 years 8 months; PDD-NOS Murdock and Hobbs (2011) 12 children between the ages of 4-6 years. Children had a diagnosis of Autism or PDD-NOS Study Table 1. (continued) Play dialogue: number of scripted and novel utterances during play Scripting (continued) Imitated request: requesting with item present after a verbal model Spontaneous request: request with item present before a verbal model Child social-communication skills: child social communication during observations Child language development: developmental measures Reinforcement and modeling Parent-mediated instruction and intervention Social initiations: number of social initiations with peers on the playground during a 15-min recess period. Physical approach (lasting at least 5 s, peer within arm’s length proximity), attending, vocal initiations Child outcome Video modeling Instructional strategy 81 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 Participant 1: male; age 3 years 6 months; autism Participant 2: male; age 5 years; autism Participant 3: male; age 5 years; autism Participant 1: female; age 4 years; PDD-NOS Participant 2: male; age 3 years; ASD Participant 3: male; age 4 years; autism Participant 1: male; age 9 years; autism Participant 2: female; age 5 years; autism Participant 3: female; age 9 years; autism Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Participant 1: male; 4 years old; autism Participant 1: male; 4 years old; autism and communication delay Gibson, Pennington, Stenhoff, and Hopper (2010) Miguel, Clark, Tereshko, and Ahearn (2009) Social communication/social interaction and challenging behavior Field et al. (1997) 22 preschool children with autism (12 male; 10 female); average age 4 years 6 months Taylor and Harris (1995) Ostryn and Wolfe (2011) Odom and Watts (1991) Study Table 1. (continued) Response interruption and redirection Functional communication training Touch therapya (continued) Orienting to irrelevant sounds: not defined, observed in the classroom Stereotypic behaviors: not defined, observed in the classroom Joint attention: Early Social Communication Scales Behavior regulation: Early Social Communication Scales Social behavior: Early Social Communication Scales Elopement: Child getting outside of his defined area on rug during circle time Appropriate request: raising hand to gain access to preferred items Vocal stereotypy: any instance of noncontextual or nonfunctional speech that included sustained vowel sounds, varying pitches of a sound, and spit swooshing at an audible level Appropriate vocalization: a request or label that was appropriate in the context Asking “What’s this?”: independently pointed to an unknown stimulus and asked the question Receptive vocabulary: pointing to the correct picture when instructed to “Point to ___” Time delay Prompting Peer social interactions: 5 min samples during two routines of the social interactions between peers with autism and typical peers (7 positive and 2 negative categories) all initiation and responses Unprompted pictorial communication: Pointing to the item and a “what’s that” card in either order Child outcome Peer-mediated instruction and intervention Instructional strategy 82 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 Participant 1: male; age 5 years; autism and Charge Syndrome Participant 2: female; age 4 years; autism Participant 3: male; age 4 years; autism Child demographics (gender, age, diagnosis, other information provided) Functional communication training Instructional strategy Challenging behavior: the percentage of direct intervals in which the student engaged in screaming, whining, biting, pinching, hitting Functional communication training skills: socially appropriate responses that were perceived as (a) equal or more efficient than problem behaviors and (b) produced the same maintaining functions as the problem behaviors Child outcome Note. Child demographics reflect information that was reported by the authors of the original study. Researchers who reported autism severity used the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1988). Information regarding instructional strategy and child outcome measures was taken from the NPDC evidencebased practice report (Wong et al., 2014). DTT = Discrete trial teaching; PDD-NOS = pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified. aThese strategies did not meet the NPDC criteria for an evidence-based practice due to insufficient evidence. Schindler and Horner (2005) Study Table 1. (continued) 83 Fleury et al. one outcome measure that improved classroom behavior or social communication/social interaction skills. However, many studies (n = 10) simultaneously decreased occurrences of challenging behavior. We defined challenging behavior as problematic behavior that may prevent the child’s and his or her or peers’ ability to learn including, but not limited to: stereotypic behavior; elopement; pushing materials away; inappropriate vocalizations; aggressive behaviors such as hitting, biting, and pinching. Improvements in classroom behavior and decreased challenging behavior were reported in six studies (24%). A total of four studies (16%) addressed both social communication or social interaction skills and challenging behavior. Figure 1 illustrates the instructional strategies that addressed specific child outcomes. Setting Based on our definitions of environmental setting, the majority of studies were based solely out of the classroom (n = 9; 36%) or in a specialized setting (n = 9; 36%). The remaining studies were conducted in the child’s home (n = 2; 8%) or in a combination of the settings (n = 5; 20%). Interventionist In the majority of the studies, the researcher (n = 11; 44%) or school personnel (n = 8; 32%) were solely responsible in delivering the intervention procedures. Parents were trained to serve as the interventionist in 16% of the studies, either as the sole interventionist (n = 2; 8%) or in combination with school personnel (n = 2; 8%). The student or peers were trained to carry out intervention procedures in 8% of the studies alongside school personnel and/ or researchers (n = 2). The exact combination of setting and interventionist classification by study is displayed in Table 2. Discussion There has been much debate regarding appropriate educational placements for children with ASD. Some studies report that children with ASD who are served in inclusive settings spend more time participating in curricular activities and demonstrate significant gains in academic achievement compared with those in self-contained settings (Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2012). Others argue that inclusive settings are less appropriate, and therefore less beneficial, for children with ASD than alternative settings in which school personnel are able to provide intensive interventions that are necessary to support the complex needs of children with ASD (Ashburner et al., 2010; Osborne & Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 84 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 st ue sp te on re eq n/ ria ati ar l atio op aliz a r ke ci iti a pp oc o A v S in M se on u c pi ty ior eo v er eha t S b t o te en lt a sa cip em fu arti op e l R p E i D ty ili tib ac str Challenging Behavior Note. This figure illustrates different instructional strategies that researchers used in studies to address classroom behavior, social communication, and/or challenging behavior in preschoolers with ASD. Information regarding instructional strategy and child outcome measures was taken from the National Professtional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC) evidence-based practice report (Wong et al., 2014). aThese strategies did not meet the NPDC criteria for an evidence-based practice. Fo s ea m al rm s re Social Communication and Social Interaction Figure 1. Intervention strategies used to improve school readiness skills. Instructional Practice Antecedent-based intervention Behavior momentuma Differential reinforcement Discrete Trial Training Exercise Functional behavior assessment Functional communication training Modeling Music therapya Parent implemented intervention Peer-mediated instruction Prompting Reinforcement Response interruption/redirection Scripting Self-management Technology-aided instruction Time delay Touch therapya Video modeling Visual support t en sk r m to e/ ta ss to age n la nc o io /c on ng ia d t n at pl on ctio low tine s enti k/e v i k m sp re l u le tt s ot or Co re di Fo ro ru A Ta M w m oo Classroom Behavior 85 Fleury et al. Table 2. Setting and Interventionist Information by Study. Setting Interventionist School Student/ Classroom 1:1 Room Home Researcher personnel Parent peer Study Classroom behavior Houlihan, Jacobson, and Brandon (1994) Kern, Wolery, and Aldridge (2007) Kleeberger and Mirenda (2010) Moore and Calvert (2000) Normand and Beaulieu (2011) Shogren, Lang, Machalicek, Rispoli, and O’Reilly (2011) Tarbox, Ghezzi, and Wilson (2006) West (2008) X X X X X X X X X X X Classroom behavior and challenging behavior Ahrens, Lerman, Kodak, Worsdell, and Keegan (2011) Call, Pabico, Findley, and Valentino (2011) Lang et al. (2011) Oriel, George, Peckus, and X Semon (2011) Reichle, Johnson, Monn, and X Harris (2010) Rispoli et al. (2011) X Social communication/social interaction Buggey, Hoomes, Sherberger, X and Williams (2011) Ganz, Flores, and Lashley (2011) Kaiser, Hancock, and Nietfeld (2000) Murdock and Hobbs (2011) Odom and Watts (1991) X Ostryn and Wolfe (2011) Taylor and Harris (1995) X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Social communication/social interaction and challenging behavior Field et al. (1997) X Gibson, Pennington, Stenhoff, X and Hopper (2010) Miguel, Clark, Tereshko, and X Ahearn (2009) Schindler and Horner (2005) X X X X X X X X X X X X X Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 X 86 Behavior Modification 39(1) Reed, 2011; Panerai et al., 2009; Reed, Osborne, & Waddington, 2012; Simpson, Mundschenk, & Heflin, 2011). Regardless of the educational setting, the relationship between social skills and academic performance has been well established by research. Children who enter formal schooling lacking social and emotional competence will likely have difficulty succeeding in school (McClelland, Morrison, & Holmes, 2000; National Center for Special Education Research, 2006). Deficits in social-communication and social interactions are a benchmark characteristic of ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These difficulties, combined with restricted, repetitive behaviors can make it especially challenging for children with ASD to fully participate in classroom activities. These behaviors may limit their access to the general education curriculum and typically developing peers, thereby reducing opportunities that children with ASD have to develop both the academic and social skills that relate to positive school outcomes. Because of characteristics associated with ASD, children with ASD may present with several behaviors that teachers will need to address if children are to benefit from classroom instruction. The results presented in this review provide practitioners and researchers with an overview of different instructional practices that have been used to prepare preschool children with ASD to engage in classroom routines and activities. Implications for Classroom Practice Children who are unresponsive to a teacher’s direction, unable to independently complete tasks, or engage in stereotypic behaviors usually cannot fully participate in, and thereby benefit from, classroom activities. Many of these behaviors, however, are amenable to early intervention. In fact, several of these behaviors were the target of interventions summarized in this review. Analyses reveal 18 evidence-based practices that directly or indirectly improved independent classroom behavior (i.e., compliance, following classroom routine, engagement in tasks), social communication and social interaction skills (i.e., making requests, social initiations, social responses), and/or reduced challenging behavior (i.e., stereotypy, refusal to participate, elopement). It should be noted that three practices that addressed school readiness—behavior momentum interventions, music, and touch therapy—did not meet the NPDC criteria to be called an evidence-based practice. Practitioners should be cautious about using these strategies until more research is published that demonstrates clear positive effects for children with ASD. In many cases, different strategies were used to address a target skill. For example, a number of studies in this review demonstrated improvements in children’s ability to attend to tasks. However, researchers took different intervention approaches to improve children’s task engagement including Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 87 Fleury et al. antecedent-based interventions (Rispoli et al., 2011), exercise (Oriel, George, Peckus, & Semon, 2011), functional behavior assessment (Kodak, Fisher, Clements, Paden, & Dickes, 2011), reinforcement (Reichle, Johnson, Monn, & Harris, 2010; Tarbox, Ghezzi, & Wilson, 2006), self-management (Shogren et al., 2011), and technology-aided instruction (Moore & Calvert, 2000). All of the intervention strategies that are included in this review are considered focused intervention practices—strategies that are designed to address a single skill or goal (Odom, Collet-Klingenberg, Rogers, & Hatton, 2010). A major advantage of focused intervention practices is that practitioners can select and combine different evidence-based practices that best suit the child’s individual needs and the learning environment. Almost half of the studies included in the present review were conducted in classrooms, and the number of studies in which school personnel delivered intervention procedures equaled those in which a researcher implemented the intervention. The applied nature of this research holds promise for having direct benefits for children with ASD who are being educated in classrooms, homes, and in specialized 1:1 settings. To improve school outcomes for children with ASD, educators must have access to empirically validated strategies such as those reported in this review. We merely provide a broad overview of strategies related to specific child outcomes in this review. If educators are expected to include these strategies as part of a child’s educational programming, this information will need to be supplemented by additional training. Pre-service and in-service educators may find publicly available training resources particularly useful such as those provided by the NPDC on ASD (http://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/) and the Autism Internet Modules available through the Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI; www.ocali.org). Implications for Research This review complements a growing body of research dedicated to helping educators provide effective classroom instruction. While previous researchers have focused on one particular learning environment such as inclusive classrooms (Crosland & Dunlap, 2012; Harrower & Dunlap, 2001), this review examined strategies that have been successfully used in different environments where learning can occur including classrooms, specialized settings, and homes. We found only a few studies (Kaiser, Hancock, & Nietfeld, 2000; Schindler & Horner, 2005) that were conducted in homes in which a caregiver served as the primary interventionist. Given that homebased experiences contribute to children’s accomplishments (Dunst, Trivette, Masiello, Roper, & Robyak, 2006) and that many young children may not be attending preschool full-time, there is a need to examine how to best support Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 88 Behavior Modification 39(1) families so they are able to implement specific strategies in their homes. In a similar vein, social validity—determining whether the focus of the intervention and behavioral changes align with the expectations of the child’s community—is an integral component of applied intervention work (Kazdin, 1982; Schwartz & Baer, 1991). The inclusion of social validity measures was not a variable of focus in this review; however, this valuable information will allow researchers to determine whether educators and families view strategies as being acceptable and the child outcomes as being relevant to their unique situations. Limitations The corpus of studies reviewed here was obtained from the NPDC database and was flagged by the NPDC reviewers as targeting school readiness. Because school readiness is a broad term that encompasses several developmental domains, we may have excluded a number of relevant studies if they were categorized under a different outcome category, such as pre-academic/ academic skills, social skills, and communication skills. This review solely focuses on a subset of skills children with ASD need to improve the likelihood that they are successful in school. It is important for us to stress that school readiness involves much more than children’s readiness. If we expect to improve academic outcomes for children with ASD, we will need to improve our knowledge about child-focused intervention strategies as well as ways to prepare families, communities, early childhood programs, and schools to create supportive environments that meet the unique needs of children with ASD (Carta, 2009; NGA, 2005). Several resources have been published about the characteristics of high-quality educational environments that incorporate developmentally appropriate practices for young children (e.g., Bredekamp & Copple, 1997; Davis, Kilgo, & Gamel-McCormick, 1998; Sandall, McLean, & Smith, 2000). Although a further description of such environments are beyond the scope of this article, we feel that it is important to emphasize that quality programs are essential for all young children, especially those with disabilities. Such environments provide a solid foundation on which practitioners can embed appropriate learning opportunities for young children with ASD (Sandall & Schwartz, 2002). For many children with ASD, however, educators will also need to provide individual support to children using specific child-focused intervention strategies. It is our intention that this review will guide educators in selecting empirically validated strategies to address specific behaviors that act as barriers to effective classroom instruction for many children with ASD. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 89 Fleury et al. Appendix Definitions of Instructional Practices Used to Address School Readiness Behavior Evidence-based practice Definition Antecedent-based intervention (ABI) Arrangement of events or circumstances that precede the occurrence of an interfering behavior and designed to lead to the reduction of the behavior. Differential reinforcement of Provision of positive/desirable consequences alternative, incompatible, for behaviors or their absence that reduce or other behavior (DRA/ the occurrence of an undesirable behavior. I/O) Reinforcement provided: (a) when the learner is engaging in a specific desired behavior other than the inappropriate behavior (DRA), (b) when the learner is engaging in a behavior that is physically impossible to do while exhibiting the inappropriate behavior (DRI), or (c) when the learner is not engaging in the interfering behavior (DRO). Discrete trial teaching (DTT) Instructional process usually involving one teacher/ service provider and one student/client and designed to teach appropriate behavior or skills. Instruction usually involves massed trials; each trial consists of the teacher’s instruction/ presentation, the child’s response, a carefully planned consequence, and a pause prior to presenting the next instruction. Exercise (ECE) Increase in physical exertion as a means of reducing problem behaviors or increasing appropriate behavior. Functional behavior Systematic collection of information about an assessment (FBA) interfering behavior designed to identify functional contingencies that support the behavior. FBA consists of describing the interfering or problem behavior, identifying antecedent or consequent events that control the behavior, developing a hypothesis of the function of the behavior, and/or testing the hypothesis. Functional communication Replacement of interfering behavior that has a training (FCT) communication function with more appropriate communication that accomplishes the same function. FCT usually includes FBA, DRA, and/or extinction. (continued) Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 90 Behavior Modification 39(1) Appendix (continued) Evidence-based practice Modeling (MD) Parent-implemented intervention (PII) Peer-mediated instruction and intervention (PMII) Prompting (PP) Reinforcement (R+) Response interruption/ redirection (RIR) Scripting (SC) Self-management (SM) Definition Demonstration of a desired target behavior that results in imitation of the behavior by the learner and that leads to the acquisition of the imitated behavior. Modeling is often combined with other strategies such as prompting and reinforcement. Parents provide individualized intervention to their child to improve/increase a wide variety of skills and/ or to reduce interfering behaviors. Parents learn to deliver interventions in their home and/or community through a structured parent training program. Typically developing peers interact with and/or help children and youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to acquire new behavior, communication, and social skills by increasing social and learning opportunities within natural environments. Teachers/service providers systematically teach peers strategies for engaging children and youth with ASD in positive and extended social interactions in both teacher-directed and learnerinitiated activities. Verbal, gestural, or physical assistance given to learners to assist them in acquiring or engaging in a targeted behavior or skill. Prompts are generally given by an adult or peer before or as a learner attempts to use a skill. An event, activity, or other circumstance occurring after a learner engages in a desired behavior that leads to the increased occurrence of the behavior in the future. Introduction of a prompt, comment, or other distracters when an interfering behavior is occurring that is designed to divert the learner’s attention away from the interfering behavior and results in its reduction. A verbal and/or written description about a specific skill or situation that serves as a model for the learner. Scripts are usually practiced repeatedly before the skill is used in the actual situation. Instruction focusing on learners discriminating between appropriate and inappropriate behaviors, accurately monitoring and recording their own behaviors, and rewarding themselves for behaving appropriately. (continued) Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 91 Fleury et al. Appendix (continued) Evidence-based practice Technology-aided instruction and intervention (TAII) Time delay (TD) Video modeling (VM) Visual supports (VS) Other Practices Behavior momentum Music therapy Touch therapy Definition Instruction or interventions in which technology is the central feature supporting the acquisition of a goal for the learner. Technology is defined as “any electronic item/equipment/application/or virtual network that is used intentionally to increase/ maintain, and/or improve daily living, work/ productivity, and recreation/leisure capabilities of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders” (Odom, Thompson, et al., 2013). In a setting or activity in which a learner should engage in a behavior or skill, a brief delay occurs between the opportunity to use the skill and any additional instructions or prompts. The purpose of the time delay is to allow the learner to respond without having to receive a prompt and thus focuses on fading the use of prompts during instructional activities. A visual model of the targeted behavior or skill (typically in the behavior, communication, play, or social domains), provided via video recording and display equipment to assist learning in or engaging in a desired behavior or skill. Any visual display that supports the learner engaging in a desired behavior or skills independent of prompts. Examples of visual supports include pictures, written words, objects within the environment, arrangement of the environment or visual boundaries, schedules, maps, labels, organization systems, and timelines. Definition Organization of behavior expectations in a sequence in which low probability/preference behaviors are embedded in a series of high probability/preference behaviors to increase the occurrence of the low probability/preference behaviors Songs and music used as a medium through which student’s goals may be addressed Systematic touch or massage Source. Evidence-based practices and definitions used in the National Professional Development Center on ASD review, Wong et al. (2014, pp. 20-22). Copyright 2014 by Samuel Odom. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 92 Behavior Modification 39(1) Authors’ Note The opinions expressed represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education through Grant R324B090005 awarded to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. References Ahrens, E. N., Lerman, D. C., Kodak, T., Worsdell, A. S., & Keegan, C. (2011). Further evaluation of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 95-108. doi:10.1901/ jaba.2011.44-95 American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 18-27. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.002 Bredekamp, S., & Copple, C. (1997). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. Buggey, T., Hoomes, G., Sherberger, M. E., & Williams, S. (2011). Facilitating social initiations of preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders using video selfmodeling. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26, 25-36. doi:10.1177/1088357609344430 Call, N. A., Pabico, R. S., Findley, A. J., & Valentino, A. L. (2011). Differential reinforcement with and without blocking as treatment for elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 903-907. doi:10.1901/jaba.2011.44-903 Carta, J. J. (2009, June). How do we get children with disabilities ready for school? In J. McLaughlin (Moderator), Panel session on enhancing school readiness, Institute of Education Sciences Research Conference, Washington, DC. Crosland, K., & Dunlap, G. (2012). Effective strategies for the inclusion of children with autism in general education classrooms. Behavior Modification, 36, 251-269. Davis, M. D., Kilgo, J. L., & Gamel-McCormick, M. (1998). Young children with special needs: A developmentally appropriate approach. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 93 Fleury et al. Dawson, G., Rogers, S. J., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., . . .Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125, 17-23. doi:10.1542/ peds.2009-0958 Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., Masiello, T., Roper, N., & Robyak, A. (2006). Framework for developing evidence-based early literacy learning practices. Center for Early Literacy Learning Papers, 1, 1-12. Field, T., Lasko, D., Mundy, P., Henteleff, T., Kabat, S., Talpins, S., & Dowling, M. (1997). Brief report: Autistic children’s attentiveness and responsivity improve after touch therapy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27, 333338. doi:10.1023/A:1025858600220 Ganz, J. B., Flores, M. M., & Lashley, E. E. (2011). Effects of a treatment package on imitated and spontaneous verbal requests in children with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46, 596-606. Gibson, J. L., Pennington, R. C., Stenhoff, D. M., & Hopper, J. S. (2010). Using desktop videoconferencing to deliver interventions to a preschool student with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29, 214-225. doi:10.1177/0271121409352873 Harrower, J. K., & Dunlap, G. (2001). Including children with autism in general education classrooms a review of effective strategies. Behavior Modification, 25, 762-784. Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 165-179. Houlihan, D., Jacobson, L., & Brandon, P. K. (1994). Replication of a highprobability request sequence with varied interprompt times in a preschool setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 737-738. doi:10.1901/jaba.1994. 27-737 Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, PL 108-466, 20 U.S.C. §1400, H.R. 1350. Kaiser, A. P., Hancock, T. B., & Nietfeld, J. P. (2000). The effects of parentimplemented enhanced milieu teaching on the social communication of children who have autism. Early Education and Development, 11, 423-446. doi:10.1207/ s15566935eed1104_4 Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2013). Interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder: Methods and recommendations. Autism, 17, 254-267. doi:10.1177/1362361312470496 Kazdin, A. E. (1982). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Kern, P., Wolery, M., & Aldridge, D. (2007). Use of songs to promote independence in morning greeting routines for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1264-1271. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0272-1 Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 94 Behavior Modification 39(1) Kieron, S. (2013). Conceptualising inclusive pedagogies: Evidence from international research and the challenge of autistic spectrum. Transylvanian Journal of Psychology, Special Issue, 52-65. Kleeberger, V., & Mirenda, P. (2010). Teaching generalized imitation skills to a preschooler with autism using video modeling. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12, 116-127. doi:10.1177/1098300708329279 Kodak, T., Fisher, W. W., Clements, A., Paden, A. R., & Dickes, N. R. (2011). Functional assessment of instructional variables: Linking assessment and treatment. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1059-1077. doi:10.1016/j. rasd.2010.11.012 Koegel, L., Matos-Freden, R., Lang, R., & Koegel, R. (2012). Interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive school settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19, 401-412. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.003 Kurth, J., & Mastergeorge, A. M. (2012). Impact of setting and instructional context for adolescents with autism. Journal of Special Education, 46, 36-48. Lang, R., Rispoli, M., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G., Andrews, A., & Ortega, L. (2011). Effects of language of instruction on response accuracy and challenging behavior in a child with autism. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20, 252-259. doi:10.1007/s10864-011-9130-0 Lloyd, J. E. V., Irwin, L. G., & Hertzman, C. (2009). Kindergarten school readiness and fourth-grade literacy and numeracy outcomes of children with special needs: A population-based study. Educational Psychology, 29, 583-602. Machalicek, W., O’Reilly, M. F., Beretvas, N., Sigafoos, J., & Lancioni, G. E. (2007). A review of interventions to reduce challenging behavior in school settings for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1, 229-246. McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: The role of learning-related social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 307-329. Miguel, C. F., Clark, K., Tereshko, L., & Ahearn, W. H. (2009). The effects of response interruption and redirection and sertraline on vocal stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 883-888. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-883 Moore, M., & Calvert, S. (2000). Brief report: Vocabulary acquisition for children with autism: Teacher or computer instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 359-362. doi:10.1023/A:1005535602064 Murdock, L. C., & Hobbs, J. Q. (2011). Picture me playing: Increasing pretend play dialogue of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 870-878. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1108-6 National Autism Center. (2009). National standards project findings and conclusions. Randolph, MA: Author. National Center for Special Education Research. (2006). Preschoolers with disabilities: Characteristics, services, and results—Wave 1 overview from the PreElementary Education Longitudinal Study (PEELS). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pdf/20063003.pdf Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 95 Fleury et al. National Governors Association. (2005). Building the foundation for bright futures: Final report of the NGA task force on school readiness. Retrieved from http:// www.nga.org/cms/home/nga-center-for-best-practices/center-publications/pageedu-publications/col2-content/main-content-list/building-the-foundation-forbrig.html Normand, M. P., & Beaulieu, L. (2011). Further evaluation of response-independent delivery of preferred stimuli and child compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 665-669. doi:10.1901/jaba.2011.44-665 Odom, S. L., Collet-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S., & Hatton, D. (2010). Evidence-based practices for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure, 54, 275-282. Odom, S. L., Thompson, J. L., Boyd, B. L., Dykstra, J., Duda, M. A., Hedges, S., Szidon, K., Smith, L., & Bord, A. (in press). Technology and secondary education for students with autism spectrum disorders. Odom, S. L., & Watts, E. (1991). Reducing teacher prompts in peer-mediated interventions for young children with autism. The Journal of Special Education, 25, 26-43. doi:10.1177/002246699102500103 Oriel, K. N., George, C. L., Peckus, R., & Semon, A. (2011). The effects of aerobic exercise on academic engagement in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 23, 187-193. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e318218f149 Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2011). School factors associated with mainstream progress in secondary education for included pupils with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1253-1263. Ostryn, C., & Wolfe, P. S. (2011). Teaching children with autism to ask “what’s that?” using a picture communication with vocal results. Infants & Young Children, 24, 174-192. doi:10.1097/IYC.0b013e31820d95ff Panerai, S., Zingale, M., Trubia, G., Finocchiaro, M., Zuccarello, R., Ferri, R., & Elia, M. (2009). Special education versus inclusive education: The role of the TEACCH program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 874882. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0696-5 Reed, P., Osborne, L. A., & Waddington, E. M. (2012). A comparative study of the impact of mainstream and special school placement on the behaviour of children with autism spectrum disorders. British Educational Research Journal, 38, 749763. doi:10.1080/01411926.2011.580048 Reichle, J., Johnson, L., Monn, E., & Harris, M. (2010). Task engagement and escape maintained challenging behavior: Differential effects of general and explicit cues when implementing a signaled delay in the delivery of reinforcement. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 709-720. doi:10.1007/s10803-0100946-6 Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M., Lang, R., Machalicek, W., Davis, T., Lancioni, G., & Sigafoos, J. (2011). Effects of motivating operations on problem and academic behavior in classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 187-192. doi:10.1901/jaba.2011.44-187 Rogers, S. J., & Vismara, L. A. (2008). Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 8-38. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 96 Behavior Modification 39(1) Sandall, S. R., McLean, M. E., & Smith, B. J. (2000). DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education. Denver, CO: Council for Exceptional Children, Division of Early Childhood. Sandall, S. R., & Schwartz, I. S. (2002). Building blocks for teaching preschoolers with special needs. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. Schindler, H. R., & Horner, R. H. (2005). Generalized reduction of problem behavior of young children with autism: Building trans-situational interventions. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 110(1), 36-47. Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1988). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services Schwartz, I. S., & Baer, D. M. (1991). Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 189-204. Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1996). Teacher perceptions of mainstreaming/ inclusion, 1958–1995: A research synthesis. Exceptional Children, 63, 59-74. Shogren, K. A., Lang, R., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M. J., & O’Reilly, M. (2011). Self- versus teacher management of behavior for elementary school students with Asperger syndrome: Impact on classroom behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13, 87-96. doi:10.1177/1098300710384508 Simpson, R. L., Mundschenk, N. A., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Issues, policies, and recommendations for improving the education of learners with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 22, 3-17. doi:10.1177/1044207310394850 Strain, P. S., & Bovey, E. (2011). Randomized, controlled trial of the LEAP model of early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 313, 133-154. Tarbox, R. S., Ghezzi, P. M., & Wilson, G. (2006). The effects of token reinforcement on attending in a young child with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 21, 155-164. doi:10.1002/bin.213 Taylor, B. A., & Harris, S. L. (1995). Teaching children with autism to seek information-acquisition of novel information and generalization of responding. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28, 3-14. doi:10.1901/jaba.1995.28-3 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs. (2013). Annual report to congress data archive: Part C child count. Available from http://ideadata.org West, E. A. (2008). Effects of verbal cues versus pictorial cues on the transfer of stimulus control for children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 23, 229-241. doi:10.1177/1088357608324715 Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., . . .Schultz, T. R. (2014). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015 97 Fleury et al. Author Biographies Veronica P. Fleury, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Special Education at the University of Minnesota. Her research is focused on facilitating learning of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), specifically identifying and validating instructional strategies to address early academic and social-communication difficulties for young children with ASD. Julie L. Thompson, PhD, BCBA, is a Research Associate in Special Education at Michigan State University. Julie conducts research examining procedures and efficiencies of using explicit group instruction to teach students with autism spectrum disorder in public school settings. She is currently working with a team investigating the use of a comprehensive approach to teach reading using behavioral and instructional supports to students with autism spectrum disorder. Connie Wong, PhD is a research investigator at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has been involved with several studies and projects involving children and youth with autism. She currently serves as the Principal Investigator of the Toddlers and Families Together study funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at MICHIGAN STATE UNIV LIBRARIES on May 13, 2015