Collaborative Writing & Peer Review in Engineering Education

advertisement

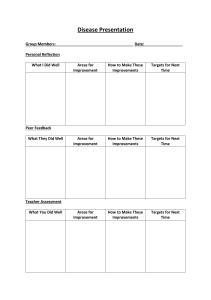

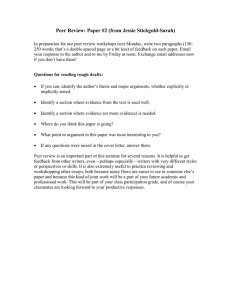

Session S2B TEACHING COLLABORATIVE WRITING AND PEER REVIEW TECHNIQUES TO ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY UNDERGRADUATES Stephanie Nelson, Ph.D. 1 Abstract - A recent survey of engineering professionals found that they spent 44% of their time writing, and almost all sometimes wrote as members of a team. Yet E&T students, who typically struggle with writing tasks, generally write as individuals and are evaluated only by their professors. This paper discusses a rationale and methods to provide students with experience in writing collaboratively and critiquing one another’s writing. I argue that collaborative writing promotes active learning and provides students with experience working as part of a team. Peer review gives students experience in critical thinking and promotes editorial skills. These classroom techniques raise students’ comfort level at having their work evaluated by others in a professional setting. Course evaluation feedback and follow-up surveying confirm that students who complete the course are more likely to write collaboratively in future courses, and students report that they will seek collaborative writing opportunities in the workplace. of E&T serves a high number of “at risk” students, defined as students who come from ethnically and educationally disadvantaged backgrounds or are non-native English speakers. Less than 70% of our E&T students succeed initially in passing the University’s Writing Proficiency Exam, which must be attempted by the second sophomore year and is a requirement for graduation. Realistically, I cannot resolve all these students’ writing problems in the 11 weeks that we are together. However, I can enculture them to consider writing as a social activity, and thus continue to actively seek feedback on their writing from experts and peers while they are in school, and hopefully later from professional colleagues when they reach the workplace. This paper describes a rationale and some methods I use for encouraging students to work collaboratively as writers. INTRODUCTION There is a widely recognized need to improve the writing skills of Engineering and Technology students. In a 1991 survey conducted by the National Society of Professional Engineers, engineering industry representatives named as the number one priority for engineering educators: “more instruction in written and oral communications” [in 2, p. 135]. This perceived gap in engineering skills is not new. Ninety years ago, a survey conducted by S.C. Earle—the socalled “father of technical writing”—found that most engineering industry representatives believed their recently hired engineering graduates “did not have adequate English skills to perform their work” [3, p. 91]. In its Engineering Criteria 2000 mission statement, ABET has amended its criteria for evaluating engineering programs to include student demonstration of “a high level of communication skills” [4]. Notice that the emphasis is on communication. Focusing on successful communication skills for our students rather than on writing per se attests to the fact that writing is fundamentally a social activity. As Dorothy Windsor has noted, “any individual’s writing is called forth and shaped by the needs and aims of the organization, and that to be understood it must draw on the vocabulary, knowledge, and beliefs other organizational members share” [5, p. 271]. Regardless of technical or grammatical accuracy, the discourse of an engineering text will fail as communication if it does not adapt to the context In my 15 years as a technical writer at a NASA center, I observed that the most successful writers sought multiple reviews of their work from their colleagues, and many actively sought mentoring from writers they perceived to be more expert. Research and development engineers who publish their work in professional journals must successfully respond to the evaluation of their peers, yet in an academic setting we typically train students to write individualistically and to “write for the teacher” rather than for an audience of their peers. For the past 3 years, I have taught a senior-level professional communication class in a College of Engineering and Technology, the first 2 years as an adjunct faculty and last year as a full-time faculty. The class is not an engineering genre-specific course—I do not instruct students to write lab reports or technical proofs—but rather the course is an introduction to the types of professional communication students will be using in the workplace, as well as the research skills they will need to access resources and stay current in their field. The writing and presentation forms the class concentrates on include memos, proposals, instructions, progress reports, news stories and press releases [see 1],1 technical presentations, résumés, cover letters, and promotional writing about technical subjects. Our College 1 RATIONALE Department of Technology, California State University, Los Angeles , Los Angeles, CA 90032-8154 0-7803-6424-4/00/$10.00 © 2000 IEEE October 18 - 21, 2000 Kansas City, MO 30 th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference S2B-1 Session S2B of the cultural situation it addresses. It must both produce shared meaning for the sender and receiver of the communication, and promote the writer as a competent member of the engineering community [6, p. 118]. Successful engineering writing entails adapting to a new discourse community and mastering its conventions for communication. While more acculturated engineering professionals are often able to read their work from the perspective of their audience and anticipate their audience’s reaction [7, p.49], novice engineering professionals do not “naturally” know the discourse of the engineering community or their audience’s expectations [8, p. 14]. This is where peer review can be extremely helpful. Educators have noted that knowledge involving judgment is best gained through collaboration, and writing is just such a process of making judgments regarding what to write about, what to say, how to say it [9]. Writing plays a critical role in learning how to think, act, and evaluate like an engineer, and writing and reviewing collaboratively can enhance that role [10]. I find that students need to be trained and coached in the peer evaluation process on an ongoing basis. I do this by providing them with evaluation checklists that they fill out for the first few assignments. An example of a checklist for an assignment is shown in Figure 1. Once students seem confident in evaluating one another’s work, I wean them from the checklists; however, if the quality of the evaluations subsequently drops, I re-instate them. I grade the team’s papers as a group, and if one team member’s paper contains excessive errors or does not fulfill the assignment, I point out to all group members that I consider the group responsible for catching these problems before I am forced to lower that particular student’s grade. I set high standards for them as professional engineering writers, along with voicing a clear expectation that I hold the group responsible for collectively solving the problem of how to demonstrate its professional writing competency to me. M ETHODS Evaluation Criteria for Memo Assignment Evaluatee___________________________ Evaluator___________________________ 1. Does the draft follow the assignment? In his recent Bloomfield Distinguished Engineering Lecture [11], Richard Felder noted that once ABET Engineering Criteria 2000 is implemented, “engineering graduates will be 2. Is the draft easy to follow and well organized overall? required to demonstrate communication and multidisciplinary teamwork skills.” Felder cites the need for 3. Is the tone of draft professional and appropriate for a business more cooperative learning activities in engineering setting? education, and notes that “several thousand studies have confirmed the effectiveness of cooperative learning in every 4. Is the purpose clear, are the memo’s conclusions appropriate, conceivable educational setting” [ibid]. Both Felder and I and is it clear what actions are being requested? prepare our students to work collaboratively by pointing out that this is now standard practice in the workplace, and by 5. Are the sentences clear and well composed stylistically? citing research findings that students who work in groups enjoy class more and get better grades [12]. To accomplish the goal of improving communication 6. Is the format correct? and teamwork skills in my class, I put my students into teams of four at the beginning of the term. I use a writing 7. Is the draft free of mechanical errors in spelling, grammar, and skills pre-test to assess current competence, and then punctuation? diversify my teams in terms of writing competency, engineering major, gender, and ethnicity. These teams sit 8. Additional comments to improve the draft: together and collaborate on writing tasks as well as review one another’s writing throughout the term. While I do not grade teams on group writing tasks, I point out continually that they are responsible for improving one another’s grades Figure 1. Typical Peer Evaluation Guidelines through the peer evaluation process. In addition, in several group writing exercises they compete against other writing Felder allows his teams to “fire” students who don’t pull teams for extra credit points. Importantly, a component of their weight, and also allows students who consistently do their grade is based on evaluation by their team members on most of the work to “quit” the group [11], but he says that their performance as a peer reviewer and their performance these options were rarely exercised. I encourage team as a collaborative task contributor [see also 13].2 I also members to come to me with problems, and there have been refuse to accept a paper from a student unless it has been peer evaluated. If they miss the peer evaluation session, they some, but I have not yet had to re-arrange teams. And I find that at the end of the term, team members are quite willing to must take the paper to our University’s Writing Center, penalize members who have not pulled their weight by where peer evaluation is also performed. 0-7803-6424-4/00/$10.00 © 2000 IEEE October 18 - 21, 2000 Kansas City, MO 30 th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference S2B-2 Session S2B evaluating them poorly in the areas where they did not perform to the level of the other team members. When students submit their peer-reviewed papers to me, I ask them to attach the comments from their team members. However, I do not require them to act on these comments unless they feel the suggestions are warranted. Peer review ideally provides students with more latitude to examine peers’ responses critically than they might feel inclined toward the teacher’s more authoritative responses. As Herrington and Cadman have remarked, “the value of peer review exchanges can be realized as much in instances where a writer decides not to follow a peer’s advice as where she does” [14, p. 185]. Peer review empowers students to make their own decisions about the value of their peer’s suggestions. In their studies of peer review in the discipline of anthropology, Herrington and Cadman also find that students often focus on substantive matters of interpretation as well as organization and style, and students reported that viewing the work of their peers helped them to work out their own ways of presenting themselves as writers within the discipline. I have reached the same conclusion about my classes, where the level of critique is sometimes lacking in substance but is nearly always thoughtful and often sophisticated, and where students almost uniformly report that the process was helpful to them. Often, even students who are having difficulties with their own writing are able to give sound advice to others—sometimes working through their own writing challenges in the process. Students have impressed me with their ability to stay on task as well as their competence at recognizing and addressing complex rhetorical issues in professional engineering writing, including context, tone, credibility, authority, and collegiality. Research on writing groups [15] shows that they: • • • • • • • • • • stakes by having them write together as a group [7]. I accomplish this in my class by presenting the group with collaborative writing exercises that are creative as well as problem-oriented. I then have the teams compete with one another and reward the winning team. An example of a collaborative writing exercise is shown in Figure 2. Collaborative writing underscores the processes of solving problems and “thinking together” that are crucial elements of today’s engineering workplace. IN-CLASS ASSIGNMENT: GROUP PRESS RELEASE Your group is being featured in the E&T Department newsletter's "Team Spirit" column of its newsletter. As a group, write a press release describing the members of your group and how the group works as a team to accomplish it s academic goals, as well as any other information you think would help to demonstrate how your group has "team spirit." There's one catch. The paper is slated for publication on April 1st. To celebrate the occasion, your group has decided to try to fool your readers by including a piece of information about the group that sounds plausible but is not true. This piece of information should be closely tied with something about the group that IS true. For instance, you might say that “helping each other as a team comes easily for our group because we are all from large families, and in addition, we are all born under the sign of Virgo, and so are very detail-oriented when it comes to editing each other's work." (This is not a very exciting example—I am sure your group can be much more creative.) After you have completed the assignment, it should be turned in to me in proper press release format, anticipating that the newsletter would likely run it just as it appears in your copy. In other words, it needs to have a title that captures the gist of the news, as well as a strong lead that captures the who, what, where, when, why, and if relevant, how. The story should be in inverted pyramid order. Underline the two "facts" about your group, and we as a class will try to guess which statement is true about your group and which is false. The group who fools the most of us will get an extra credit point. Figure 2. Typical Group Writing Assignment Improve judgment and critical thinking skills Improve organization and appropriateness Improve students’ ability to direct others Improve reflexive understanding of writing as a mode of discourse and a process Provide students with a better sense of their audience Improve language usage Increase the amount of student revising done Reduce student apprehension about writing Expose students to a wider variety of ideas and styles Decrease teacher grading load! However, as Kathryn Riley comments in her article about habits of highly effective writers, peer reviewing can be helpful in an editorial sense but more often on only superficial features. To move teams toward a more synergistic and creative relationship, she suggests raising the Although I do not require the teams to meet outside of the classroom, I have noticed that they will often arrange voluntarily to help one another with a writing task, do a late peer review, or even study together for the mid-term or final. An additional benefit of collaborative writing is that it gives the more accomplished writers in the class—who might already be quite competent and thus unchallenged with much of the class content—the opportunity to step into my role as expert and teach other students. ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION As stated above, I have been teaching this course primarily as an adjunct and have not developed an integral enough relationship with my students or the Department for students to return to me with testimonials of its success in preparing them as professional engineering communicators. Therefore it is the intention of this paper to present a summary of my 0-7803-6424-4/00/$10.00 © 2000 IEEE October 18 - 21, 2000 Kansas City, MO 30 th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference S2B-3 Session S2B methods and general evaluations from students as to their perceived value to them. However, next year I will join the faculty as a full-time tenure-track member, and I am in the process of developing an assessment plan that will provide more accurate information about whether the outcomes for the class are as I suspect. My own substantial tenure as a professional communicator in an engineering environment convinces me that viewing writing as a social process is critical to one’s success in the workplace, and this has been confirmed by students ancedotally. Students who are working in engineering firms while enrolled in the class have commented that they are learning skills and techniques that are immediately useful to them in their work. Recently, two alumni of my class told me that when faced with a team project in another class, they were the only team who literally wrote collaboratively rather than compiling individual writings, and that they got the highest grade of all teams on their project. The professor who taught this course also confirmed that their report excelled because it was more fully integrated, better organized, and less repetitive than other team reports. Our department, while not accredited by ABET,3 is putting together an extensive assessment plan, and technical communication competency is being assessed since it is an outcome that cuts across all programs. In addition to being a University-wide goal, it has also been identified as high importance/low performance outcome by our industry stakeholders in initial surveys. The assessment questionnaire will go to senior students, alumni, and student employers (stakeholders). In addition to questions we plan to ask regarding technical communication competency in general, questions I plan to ask regarding peer evaluation and collaborative writing specifically are the following: • I [my employees] seek feedback from their peers on their technical communication projects (memos, reports, presentations, etc.) before disseminating final versions. • I [my employees] seek advice on their technical communication projects from more senior or expert members of the organization. • I [my employees] have written collaboratively on one or more occasions. This data, when we implement the study next year, will provide me with a more accurate assessment of the outcomes of my course goals. In the meantime, in present standardized course exit evaluations, students tend to focus their comments on my performance and the contents of the course rather than on their peer review work. A typical comment is as follows: I think students’ focus on teaching and course content underscores that students are just as ingrained as their teachers in viewing knowledge as something that is transferred to them by experts and then carried around in their heads, rather than something that is socially constructed in response to specific contexts and settings. An example of this view is encapsulated in one of the few negative comments I’d had about group work: I found the group work to be time wasted. I would rather hear from the instructor. Despite this criticism, I do believe that students’ collaborative experiences are fundamental to empowering them as communicators and to encouraging positive social actions in their academic and professional lives that will promote their continued growth as engineering communicators. When prompted to consider this more carefully, as I believe will be the case in the assessment process, I believe students will reflect on and recognize the value of peer review and collaborative writing. I close this paper with additional comments from student evaluations on collaborative writing and peer review. I found that working with teams was much easier and fun. I was able to meet other classmates and use their skills to resolve my assignment problems. I enjoyed the group work and peer sessions. What was nice was that it was done in class and we worked well together. I enjoyed working with others in different fields. I learned a lot from them and would recommend this again. Dividing groups depending on pre-exam results was a good idea that made me work effectively with other group members. Peer assignments helped the class get other students’ perspectives on different writing assignments. I really enjoyed the group work. We had fun in class and the environment was fun and relaxing. It was an enjoyable way to work. *** END NOTES 1 It is great to have a teacher who knows the class material. Thank you, I’ve learned a lot. By the way, group work is a good idea. I teach journalistic writing techniques in this class for several reasons. First, I find my students have had little classroom exposure to this writing style, which is pervasive in our society. Second, writing in scientific fields has increasingly taken a more news-oriented turn, with the most 0-7803-6424-4/00/$10.00 © 2000 IEEE October 18 - 21, 2000 Kansas City, MO 30 th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference S2B-4 Session S2B important information and results foregrounded [1]. Managers of engineering organizations increasingly expect this kind of reporting of technical information. 2 I ask students to rate other group members on a scale of 5 to 1, corresponding to excellent, very good, adequate, needs improvement, or poor, on the following criteria: 1) This group member was always prepared and willing to contribute to group assignments, 2) This group member gave me valuable feedback on my work, 3) This group member made a valuable contribution to our group’s teamwork efforts. An additional successful group evaluation method is to have group members rank their group’s performance (including their own) or else spread 100 points according to each member’s level of contribution (again, including their own). [See 14]. 3 The Technology Department falls under the professional umbrella of the National Association for Industrial Technology, and thus far we have opted as a department not to seek accreditation for various reasons. [10] Herrington, A. J., “Writing in Academic Settings: A Study of the Contexts for Writing in Two College Chemical Engineering Courses,” Research in the Teaching of English, 19(4), Dec. 1985, 331-361. [11] Felder, R. M., “Educating Tomorrow’s Engineers.” Bloomfield Distingished Engineering Lecture, Wichita, KS: Wichita State University, Nov. 4, 1999. [12] Carnevale, A. P., Gainer, L. J., and Meltzer, A. S., 1988. Workplace Basics: Skills Employers Want. Washington D.C.: The American Society for Training and Development and the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. [13] Catanach Jr., A. H., and Rhoades, S. C., “A Practical Guide to Collaborative Writing Assignments in Financial Accounting Courses,” Issues in Accounting Education, 12(2), Fall 1997, 521-537. [14] Herrington, A. J., and Cadman, D., “Peer Review and Revising in an Anthropology Course: Les sons for Learning,” College Composition and Communication, 42(2), May 1991, 184-199. [15] Gere, A. R. , and Abbott, R. D, “Talking About Writing: The Language of Writing Groups,” Research in the Teaching of English, 19(4), Dec. 1985, 362-381. REFERENCES [1] Berkenkotter, C., and Huckin, T., “News Value in Scientific Journal Articles.” Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication: Cognition/Culture/ Power. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc., 1995. [2] Landis , R. B. Studying Engineering: A Road Map to a Rewarding Career. Burbank, CA: Discovery Press. 1995. [3] Kynell, T. “English as an Engineering Tool: Samuel Chandler Earle and the Tufts Experiment.” J. Technical Writing and Communication, 25(1), 1995 85-92. [4] Director, Engineering Accreditation Commission, ABET, “Engineering Criteria 2000,” Baltimore, MD, 1999. [5] Windsor, D. A., “An Engineer’s Writing and the Corporate Construction of Knowledge,” Written Communication 6(3), July 1989, 270-285. [6] McGo wan, U., Seton, J., and Cargill, M., “A Collaborating Colleague Model for Inducting International Engineering Students into the Language and Culture of a Foreign Research Environment,” IEEE Trans. Professional Communication, 39(3), Sept. 1996, 117-121. [7] Riley, K., “Seven Habits of Highly Effective Writers,” IEEE Trans. Professional Communication, 42(1), March 1999, 4751. [8] Walker, K., “Using Genre Theory to Teach Students Engineering Lab Report Writing,” IEEE Trans. Professional Communication, 42(1), March 1999, 12-19. [9] Henschen, B. M., and Sidlow, E. I., “Collaborative Writing,” College Teaching, 38(1), Winter 1990, 29-32. 0-7803-6424-4/00/$10.00 © 2000 IEEE October 18 - 21, 2000 Kansas City, MO 30 th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference S2B-5