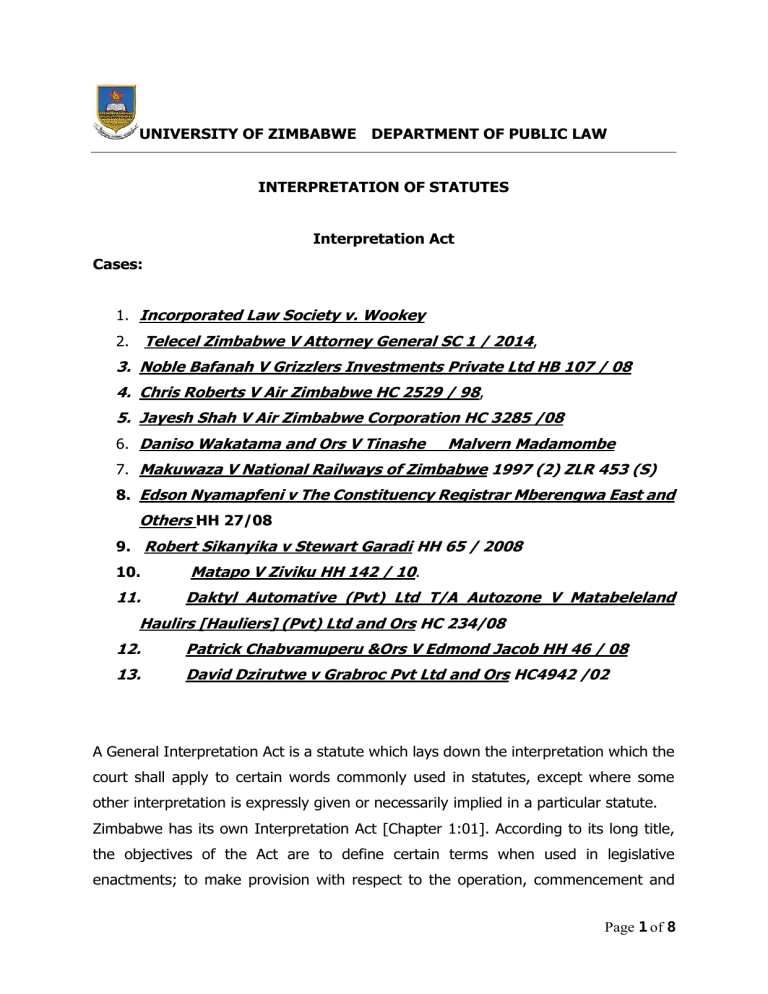

UNIVERSITY OF ZIMBABWE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC LAW INTERPRETATION OF STATUTES Interpretation Act Cases: 1. Incorporated Law Society v. Wookey 2. Telecel Zimbabwe V Attorney General SC 1 / 2014, 3. Noble Bafanah V Grizzlers Investments Private Ltd HB 107 / 08 4. Chris Roberts V Air Zimbabwe HC 2529 / 98, 5. Jayesh Shah V Air Zimbabwe Corporation HC 3285 /08 6. Daniso Wakatama and Ors V Tinashe Malvern Madamombe 7. Makuwaza V National Railways of Zimbabwe 1997 (2) ZLR 453 (S) 8. Edson Nyamapfeni v The Constituency Registrar Mberengwa East and Others HH 27/08 9. Robert Sikanyika v Stewart Garadi HH 65 / 2008 10. Matapo V Ziviku HH 142 / 10. 11. Daktyl Automative (Pvt) Ltd T/A Autozone V Matabeleland Haulirs [Hauliers] (Pvt) Ltd and Ors HC 234/08 12. Patrick Chabvamuperu &Ors V Edmond Jacob HH 46 / 08 13. David Dzirutwe v Grabroc Pvt Ltd and Ors HC4942 /02 A General Interpretation Act is a statute which lays down the interpretation which the court shall apply to certain words commonly used in statutes, except where some other interpretation is expressly given or necessarily implied in a particular statute. Zimbabwe has its own Interpretation Act [Chapter 1:01]. According to its long title, the objectives of the Act are to define certain terms when used in legislative enactments; to make provision with respect to the operation, commencement and Page 1 of 8 interpretation of legislative enactments; to shorten the language of legislative enactments; and for other purposes.” The interpretation Act is the first Act in our statute books because it provides the rules by which every other statute that follows should be interpreted. The rules of interpretation in the Act are not exhaustive. In fact the bulk of the rules on interpretation currently in use today are not provided for in the interpretation Act. The Act supplements the common law rules sometimes modifying them and sometimes codifying them Part 1: Preliminary Sections 1 and 2 Section 2 of the Act talks about the application of the Act. It states that, “the provisions of this Act shall extend and apply to every enactment as defined in this Act, including this Act, which was in force in Zimbabwe immediately before the 1st November, 1962, or thereafter comes into force in Zimbabwe, except in so far as any such provisions are inconsistent with the intention or object of such enactment; or would give to any word, expression or provision of any such enactment an interpretation inconsistent with the context; or are in such enactment declared not applicable thereto. Nothing in this Act shall exclude the application to any enactment of any rule of construction applicable thereto and not inconsistent with this Act.” An immediate observation is that common law is excluded from application of the Interpretation Act and that the common law rules of interpretation are not excluded as long as they are not inconsistent with the Act. Part 2: Definitions Sections 3 Section 3 is a general dictionary of the terms used in statutes. Nearly every Act however contains its own internal dictionary of the terms and words used in that statute, usually in section 2. When looking for a definition of a particular word, an interpreter should look first for a definition in the statute under consideration. If he Page 2 of 8 cannot find it there he should look to the Interpretation Act. If the term is not defined in the interpretation Act, he can then resort to a dictionary meaning. An example of a general definition laid down by the Act is that “Minister” means ‘A Minister of the Government’. However, the context of a particular statute may indicate an intention to confine the word to a particular class e.g. persons to males only. In Incorporated Law Society v. Wookey1the court held that section 20 of the Cape Charter of Justice 1832, empowering the Supreme Court to admit and enroll as its attorneys certain persons with prescribed qualifications did not include women, since at the time of the promulgation of the Charter the common law had excluded women from becoming attorneys, this had been the position from time immemorial. See: Telecel Zimbabwe V Attorney General SC 1 / 2014, where the court confirmed that the word person as used in section 14 of the Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act includes juristic person as provided for in section 3(3) of the interpretation Act Part 3: General Provisions Regarding Enactments Sections 4 - 15 This section of the Act deals with the applicability of internal aids to interpretation which have been dealt with in this course. Section 4 provides that enactments apply to the whole of Zimbabwe unless the context suggests otherwise. Of course local authority by laws apply only to the area under the jurisdiction of the local authority making the bylaw Section 5 provides in essence that failure to adhere strictly to a statutory form shall not by itself, render the form invalid and also that a form need not be published in the gazette if the statute identifies an office from where it can be obtained. Section 6 confirms the common law position that the preamble to a statute and punctuation form part of the statute and may be used as internal aids to interpretation. The Act does not however identify what is a preamble or say how it may be used. This is significant because in several cases, judges seem to regard the long title as the 1 Incorporated law Society v. Wookey 1912 AD 558 Page 3 of 8 preamble see Noble Bafanah V Grizzlers Investments Private Ltd HB 107 / 08 where the Bere J. referred to “ the preamble of the Contractual Penalties Act” when that Act does not have a preamble and what he was really referring to was the long title. In Chris Roberts V Air Zimbabwe HC 2529 / 98, Hungwe J referred to the long tile of the Carriage by Air Act as the preamble. That Act does not have a preamble. See also Jayesh Shah V Air Zimbabwe Corporation HC 3285 /08 Section 7 provides that headings, notes, tables and indexes do not form part of the statute and therefore should not be regarded as internal aids to interpretation Section 8 provides that Writing and expressions referring to writing shall be construed as including printing, typewriting, lithography, photography and any other modes of representing or reproducing words or figures in a visible form. With developments in modern technology, this may be expanded to include scanning and photocopying Section 9 provides that words importing one gender includes the other gender as well as juristic persons. (Telecel Zimbabwe V Attorney General SC 1 / 2014, ). References importing singular also includes the plural It also looks at other rules of interpretation to be applied to statutes such as section 11 which say that enactments are always speaking and if anything is expressed in the present tense it shall be applied to the circumstances as they occur so that effect may be given to each enactment according to its true spirit, intent and meaning. Section 15B provides for the use of extrinsic aids to interpretation. Introduced in 2003, this section seeks to codify the common law rules regulating the use of extrinsic material. Section 15B(2)(d) provides that any treaty, convention or other international agreement that is referred to in the enactment;is an extrinsic aides. This provision has been overtaken by section 327(6) of the Constitution. That section provides: When interpreting legislation, every court and tribunal must adopt any reasonable interpretation of the legislation that is consistent with any international convention, treaty or agreement which is binding on Zimbabwe, Page 4 of 8 in preference to an alternative interpretation inconsistent with that convention, treaty or agreement. We can see that the role of international treaties under section 327(6) of the Constitution is wider than that envisaged under section 15B in that while under section 15B, the court is only permitted to refer to any agreement that is referred to the enactment, under section 327(6) of the Constitution, the court must refer to any treaty which is binding on Zimbabwe even if such treaty has not been referred to in the enactment under consideration. Part 4: Repeal, Re-enActment and Amending Legislation Sections 16 - 19 The part focuses on the effect of the repealing, re-enacting and amending of an Act or certain sections of an Act. Section 17 of the Act states that, “Where an enactment repeals another enactment, the repeal shall not (a) revive anything not in force or existing at the time at which the repeal takes effect; or (b) affect the previous operation of any enactment repealed or anything duly done or suffered under the enactment so repealed; or (c) affect any right, privilege, obligation or liability acquired, accrued or incurred under the enactment so repealed; or (d) affect any offence committed against the enactment so repealed, or any penalty, forfeiture or punishment incurred in respect thereof; or (e) affect any investigation, legal proceeding or remedy in respect of any such right, privilege, obligation, liability, penalty, forfeiture or punishment as aforesaid and any such investigation, legal proceeding or remedy shall be exercisable, continued or enforced and any such penalty, forfeiture or punishment may be imposed as if the enactment had not been so repealed.” Section 18 talks of the effects of substituted provisions. Part 5: Statutory Instruments Sections 20 – 23 Page 5 of 8 The issue of commencement of statutory instruments and the power to create them is also talked about. The application of the Act to bi-laws and regulations is also found in this section. Part 6: Powers and Appointments Sections 24 - 30 Here the powers conferred by statutes are enunciated as well as how and by whom they may be exercised. Section 28 provides that an enactment which confers power to make an appointment of a person to any office or post shall confer on the appointing authority— (a) power at the discretion of that authority to remove or suspend him; In the case of Daniso Wakatama and Ors V Tinashe Malvern Madamombe SC 10 / 12, it was however ruled that this section will not apply where the statute in question has provided otherwise. Part 7: Evidence section 31 and 32 The evidence of the operation of a statute is discussed. In section 32(1) it is said that it shall be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that any enactment which has been published in the Gazette has been duly made, and all courts shall take judicial notice of any such enactment. Part 8: Time and Distance Sections 33 and 34 This section is about reference to time as being the time in Zimbabwe section 34 says that the measurement of any distance for the purposes of any enactment, that distance shall be measured in a straight line on a horizontal plane. Section 33 provides for the computation of time In The case of Makuwaza V National Railways of Zimbabwe 1997 (2) ZLR 453 (S) it was held that where an enactment refers to a period of time numbered in days, Page 6 of 8 Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays are included in the period unless the enactment specifically provides otherwise. Edson Nyamapfeni v The Constituency Registrar Mberengwa East and Others HH 27/08 “The clear meaning of s 33 (1) to (4) is as follows. Subsection one spells out that s 33 defines any reference to time in any enactment in Zimbabwe. Subsection two excludes the day on which the event triggering the reckoning of time occurred, meaning the reckoning of time starts from the next day. Subsection three includes the last day of the stated period in the reckoning of time. Subsection four extends the period if the last day falls on a Saturday, a Sunday or a public holiday, to the next day which is not a Saturday, a Sunday or a public holiday. The inclusion of subsection four providing for extension to the following day if the period expires on a Saturday, a Sunday or a public holiday means Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays are included in the reckoning of time. 33(6)(c) of the Act provides that “In an enactment— a reference to a month shall be construed as a reference to a calendar month; See also Robert Sikanyika v Stewart Garadi HH 65 / 2008 The case of Matapo V Ziviku HH 142 / 10.ruled that Since the Act does not define a calendar month, The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines it as: “One of the twelve months into which the year is divided according to the calendar; also the space of time from any date (e.g. the 17th) of any month to the corresponding date (the 17th) of the next, as opposed to a lunar month of 4 weeks.” Taking the above definition, in computing time in the present matter the court will take the date in any particular month to a corresponding date to any other month. Mr Mutangadura submitted that a calendar month is the beginning of the month to the end of that month. If one were to use that method it would present problems with any dates that fall between the beginning and the end Page 7 of 8 of a particular month. It would leave such periods unaccounted for, which in my view was not the intention of the legislature when s 33 (6) was enacted. This ruling seems to be at odds with the conclusion reached by Ndou J in the case of Daktyl Automative (Pvt) Ltd T/A Autozone V Matabeleland Haulirs [Hauliers] (Pvt) Ltd and Ors HC 234/08 where he said the following: In terms of section 33 (6) (c) of the Interpretation Act [Chapter 1:10] a month is as it stands in the calendar e.g. 1 December to 31 December 2008. In the circumstances, no month begins from the middle of the month and end in the middle of another. A calendar month runs from the beginning of a month to an end of that month. Part 9: Miscellaneous sections 35 - 41 Section 40 provides for the manner in which documents should be served but Parliament my provide for a different manner of service in a particular Act, in which case service should be effected as provided for in that other Act. For example, section 69 of the Electoral Act provides for a specific manner in which election petitions should be served. See Patrick Chabvamuperu &Ors V Edmond Jacob HH 46 / 08 See also David Dzirutwe v Grabroc Pvt Ltd and Ors HC4942 /02 Page 8 of 8