Glyn Salton-Cox - Queer Communism and the Ministry of Love Sexual Revolution in British Writing of the 1930s-Edinburgh University Press (2018)

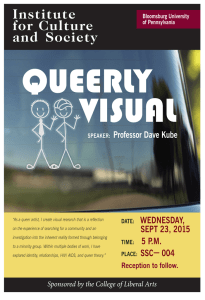

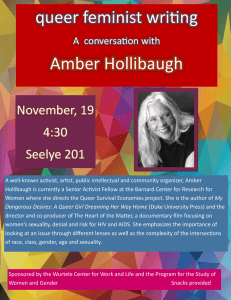

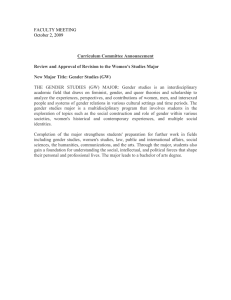

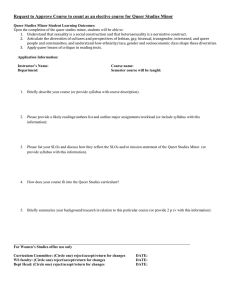

advertisement