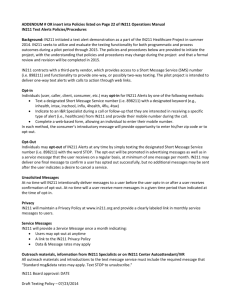

Research Letter | Public Health Effect of Opt-In vs Opt-Out Framing on Enrollment in a COVID-19 Surveillance Testing Program The COVID SAFE Randomized Clinical Trial Allison H. Oakes, PhD; Jonathan A. Epstein, MD; Arupa Ganguly, PhD; Sae-Hwan Park, PhD; Chalanda N. Evans, BS; Mitesh S. Patel, MD, MBA Introduction + Supplemental content The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused workplaces and campuses to close or shift many Author affiliations and article information are listed at the end of this article. people to remote work. To safely reopen, surveillance testing is needed to help to identify asymptomatic and presymptomatic cases.1,2 We conducted a clinical trial to rapidly implement and scale a saliva-based method for COVID-19 surveillance testing.3 However, participation in clinical trials is often suboptimal. In prior work,4,5 opt-out framed recruitment strategies have shown promise for increasing program enrollment; this approach may leverage status quo bias. In this randomized clinical trial, we tested the effect of an opt-out framed recruitment strategy compared with a conventional opt-in strategy on enrollment and initial adherence to a COVID-19 testing program. Methods The COVID-19 Screening Assessment for Exposure Trial (COVID SAFE) was a randomized clinical trial conducted between September 9, 2020, and October 30, 2020 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04506268). The trial protocol (Supplement 1) was approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. On the basis of power calculations informed by the existing literature, participants were electronically randomized into opt-out and opt-in groups using a 1:2 allocation ratio.4,5 Eligible participants included faculty, staff, and students at the University of Pennsylvania who were aged 18 years or older, on campus at least 1 day per week, and owned a smartphone. Recruitment emails were sent from the Office of the Executive Vice Dean. Those in the opt-in group were emailed an invitation to enroll and given a link to get more information, whereas those in the opt-out group were told they were conditionally enrolled and given a link to complete the process. The study was conducted using Way to Health, a research platform at the University of Pennsylvania. Interested participants accessed the study website to create an account, provide informed consent, and complete surveys. Participants were asked to complete a biweekly saliva-based COVID-19 screening test for up to 6 months. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants who enrolled within 4 weeks of invitation. The secondary outcome was the proportion of participants who completed their first scheduled screening test. We fit models for the outcome measures according to generalized estimating equations with a logit link and an exchangeable correlation structure using participant as the clustering unit. The model included participant age, sex, race/ethnicity, and date of invitation. Race/ethnicity was assessed because enrollment in clinical trials is suboptimal, and the characteristics of enrolled individuals are often not representative of the general population. Recent work5 suggests that opt-out framing might help address this issue. At the point of invitation, race/ethnicity data came Open Access. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(6):e2112434. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12434 (Reprinted) Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by guest on 02/17/2024 June 3, 2021 1/4 JAMA Network Open | Public Health Effect of Opt-In vs Opt-Out Framing on Enrollment in a COVID-19 Surveillance Testing Program from administrative employment records. The categories were determined on the basis of a combination of prior work and the distribution of data. To obtain the adjusted difference and 95% CIs between groups, we used the bootstrap method, resampling participants 2000 times. Investigators and data analysts were blinded to group assignments until the analysis was completed. Two-sided hypothesis tests used an α of .05. Analyses were conducted using the Python statsmodel module version 0.12.1 (Python). Data analysis was conducted from October to December 2020. Results A total of 1759 participants were randomized (eFigure in Supplement 2). Baseline characteristics were similar among groups, including age (mean [SD] age, invited opt-in group, 40.2 [13.3] years; invited opt-out group, 40.0 [13.0] years; enrolled opt-in group, 38.1 [13.3] years; and enrolled opt-out group, 38.8 [12.9] years), sex (invited opt-in group, 566 men [50.4%]; invited opt-out group, 268 men [47.7%]; enrolled opt-in group, 107 men [41.8%]; enrolled opt-out group, 75 men [48.1%]), and race/ethnicity (invited opt-in group, 581 White participants [49.5%]; invited opt-out group, 253 White participants [43.2%]; enrolled opt-in group, 161 White participants [62.9%]; and enrolled Table 1. Participant Characteristics Participants, No. (%) Invited Enrolled Characteristic Opt-in (n = 1173) Opt-out (n = 586) P value Opt-in (n = 256) Opt-out (n = 156) P value Age, mean (SD), y 40.2 (13.3) 40.0 (13.0) .67 38.1 (13.3) 38.8 (12.9) .59 Sex Male 566 (50.4) 268 (47.7) Female 557 (49.6) 294 (52.3) 107 (41.8) 75 (48.1) 149 (58.2) 81 (51.9) White 581 (49.5) Black 146 (12.4) 253 (43.2) 161 (62.9) 89 (57.1) 78 (13.3) 9 (3.5) Asian 282 (24.0) 158 (27.0) 7 (4.5) 47 (18.4) 35 (22.4) .31 .25 Race/ethnicity Non-Hispanic .05 Hispanic 34 (2.9) 12 (2.0) 10 (3.9) 5 (3.2) Multiple or other races/ethnicitiesa 130 (11.1) 85 (14.5) 29 (11.3) 20 (12.8) <50 000 NA NA 63 (24.6) 41 (26.3) 50 000-100 000 NA NA 74 (28.9) 44 (28.2) >100 000 NA NA 119 (46.5) 71 (45.5) Some high school or less NA NA 2 (0.8) 0 (0.0) Some college or specialized training NA NA 7 (2.7) 6 (3.8) College graduate or higher NA NA 247 (96.5) 150 (96.2) .75 Annual household income, $ NA .93 Education NA .45 Abbreviation: NA, not applicable. a Other includes Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaska Native. Table 2. Trial Outcomes Participants, No. (%) Outcome measures Opt-in (n = 1173) Opt-out (n = 586) Adjusted difference vs opt-in, % (95% CI) P value Trial enrollment 256 (21.8) 156 (26.6) 5.1 (1.0 to 9.3) .01 Conditioned on enrollment 224 (87.5) 133 (85.3) −2.1 (−8.9 to 4.2) .54 Total 224 (19.1) 133 (22.7) 3.9 (0.0 to 8.1) .04 Completion of first test JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(6):e2112434. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12434 (Reprinted) Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by guest on 02/17/2024 June 3, 2021 2/4 JAMA Network Open | Public Health Effect of Opt-In vs Opt-Out Framing on Enrollment in a COVID-19 Surveillance Testing Program opt-out group, 89 White participants [57.1%]) (Table 1). Between study groups, enrolled participants also did not differ in terms of self-reported income or education (Table 1). The opt-out group had significantly greater enrollment than the opt-in group (26.6% [156 of 586] vs 21.8% [256 of 1173 ]; adjusted difference, 5.1 percentage points; 95% CI, 1.0 to 9.3 percentage points; P = .01) (Table 2). Among enrolled participants, there was no difference in first test completion (−2.1 percentage points; 95% CI, −8.9 to 4.2 percentage points; P = .54), but across the total sample the opt-out group had significantly greater first test completion (3.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.0 to 8.1 percentage points; P = .04). Discussion In this randomized clinical trial, an opt-out framed recruitment strategy increased enrollment into a COVID-19 screening program and increased the overall rate of test completion. This study is limited to a single academic health system. If applied more broadly, the increase of 5.1 percentage points may have substantial implications for uptake. This study is one of the first to examine the effect of default options on enrollment in a COVID-19–related program. These findings could inform other health promotion efforts needed to address the COVID-19 pandemic.6 ARTICLE INFORMATION Accepted for Publication: April 7, 2021. Published: June 3, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12434 Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2021 Oakes AH et al. JAMA Network Open. Corresponding Author: Allison H. Oakes, PhD, VA Health Services Research & Development Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 3900 Woodland Ave, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (alli.oakes@gmail.com). Author Affiliations: VA Health Services Research & Development Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Oakes, Patel); Penn Medicine Nudge Unit, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Oakes, Park, Evans, Patel); Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Epstein, Ganguly, Patel); Genetic Diagnostic Laboratory, Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Ganguly); Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Patel). Author Contributions: Drs Oakes and Patel had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Oakes, Epstein, Evans, Patel. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Oakes, Ganguly, Park. Drafting of the manuscript: Oakes, Park, Evans. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Oakes, Epstein, Ganguly, Park, Patel. Statistical analysis: Oakes, Park. Obtained funding: Epstein, Patel. Administrative, technical, or material support: Epstein, Ganguly, Evans. Supervision: Epstein, Evans, Patel. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Oakes reported receiving support from the Department of Veterans Affairs Advanced Fellowship Program in Health Services Research & Development. Dr Patel reported being a founder of Catalyst Health, a technology and behavior change consulting firm; being an advisory board member for Healthmine Services Inc, LifeVest Health, and Holistic Industries; and receiving research funding from Deloitte, which is not related to the work described in this article. No other disclosures were reported. Funding/Support: Funding for this work was provided by the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Pennsylvania Health System through the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(6):e2112434. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12434 (Reprinted) Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by guest on 02/17/2024 June 3, 2021 3/4 JAMA Network Open | Public Health Effect of Opt-In vs Opt-Out Framing on Enrollment in a COVID-19 Surveillance Testing Program Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Disclaimer: The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. Additional Contributions: Sarah Fendrich, BA, Ai Leen Oon, BA, Kayla Clark, BA, Penn Medicine, and Andrew Parambath, BA (all at Penn Medicine), assisted with COVID SAFE program administration and management. Frederic Bushman, PhD (Penn Medicine), Scott Sherrill-Mix, PhD (Penn Medicine), and the University of Pennsylvania Rapid Assay Task Force provided guidance on assay development. Dorothy Leung, MA (Penn Medicine), assisted with program administration. None of these individuals was compensated beyond their regular salary. REFERENCES 1. Rafiei Y, Mello MM. The missing piece—SARS-CoV-2 testing and school reopening. N Engl J Med. 2020;383 (23):e126. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2028209 2. Paltiel AD, Zheng A, Walensky RP. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening strategies to permit the safe reopening of college campuses in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2016818. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2020.16818 3. Sherrill-Mix S, Hwang Y, Roche AM, et al. LAMP-BEAC: detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using RT-LAMP and molecular beacons. medRxiv. Published online April 16, 2021. doi:10.1101/2020.08.13.20173757 4. Mehta SJ, Khan T, Guerra C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of opt-in versus opt-out colorectal cancer screening outreach. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(12):1848-1854. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0151-3 5. Aysola J, Tahirovic E, Troxel AB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of opt-in versus opt-out enrollment into a diabetes behavioral intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(3):745-752. doi:10.1177/0890117116671673 6. Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Buttenheim AM. Behaviorally informed strategies for a national COVID-19 vaccine promotion program. JAMA. 2021;325(2):125-126. SUPPLEMENT 1. Trial Protocol SUPPLEMENT 2. eFigure. CONSORT Diagram SUPPLEMENT 3. Data Sharing Statement JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(6):e2112434. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12434 (Reprinted) Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by guest on 02/17/2024 June 3, 2021 4/4