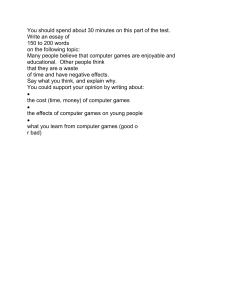

Essay Writing Understanding the Process DENNIS FARRUGIA RUTH LEE ROS GILCHRIST MARGARET KUMAR HARVEY BROADSTOCK DEAKIN UNIVERSITY Published by Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria 3217, Australia First published 1994 Second edition 2001 Third edition 2004 © Deakin University 2001 Reprinted 2002, 2003, 2004 Designed and typeset by Learning Services, Deakin University Printed by Deakin Print Services, Deakin University ISBN 0 7300 2799 6 Contents Introduction The Deakin student The purpose of this guide The process of essay writing 1 1 1 2 Step 1: Analysing the question (a) Things to note immediately (b) Deconstructing the question (c) Brainstorming the question (d) Making a preliminary plan for your research 3 3 3 5 6 Step 2: Reading and making notes (a) Reading (b) Making notes 7 7 9 Step 3: Making essay plans (a) Concept mapping (b) Making a list 11 12 13 Step 4: Writing the essay (a) Essay structure—crafting the introduction, body and conclusion (b) Common problems and ways to fix them 14 14 15 Step 5: Editing (a) Editing for logic and coherence (b) Editing for style and expression (c) Editing for spelling, grammar and punctuation (d) Proofreading 17 17 17 18 18 Step 6: Citing your sources (a) Plagiarism (b) Referencing styles—Harvard and Oxford (c) Bibliographies (d) Citing electronic sources 19 19 19 21 21 Conclusion 22 Further reading Texts on academic writing Deakin University style manuals Dictionaries and editorial style manuals 23 23 23 23 Essay structure exercise Sample essay 25 25 Feedback Introduction The Deakin student Deakin University has identified a number of attributes which it aims to develop in all its graduates. It is envisaged that students will develop these qualities while at Deakin and continue to extend them throughout their lifetime. The achievement of this goal is known as the Deakin Advantage. It is hoped that you, as a student, will not only become an expert in your field of study but will develop skills to ensure that your future career and lifelong learning experiences are more fulfilling. Among the personal skills which Deakin graduates should develop are: • a good standard of oral and written communication and presentation; and • an ability for critical thinking, analysis and problem solving. Discipline specific attributes include the ability to identify, gather, retrieve and operate with textual, graphical and numerical information. These skills, which will develop progressively during your course, are all part of the essay writing process. The purpose of this guide If you are starting out at university we hope that this guide will demystify the often assumed skill of essay writing. If you are further on in your course it may provide you with a tool with which to improve your technique and refresh your memory. If you have always been able to write good essays ‘intuitively’ this guide will make explicit many of the processes that you may be already using successfully. Remember that you are part of a bigger picture at university. Through essay writing you are actually being trained in the same process that practising academics use when they are writing articles for publication. This is the main way that academics communicate their research— through writing conference papers, articles and books. Through your writing you are being trained as ‘apprentice academics’. Another principle, particularly in the arts and social sciences, is that you will often be required to produce your essays in the form of an argument. However, the argument cannot use devices commonly used in speech, such as persuasive or emotional language. You need to make your argument clear through presenting a logical order of points, backed up in each case by evidence gleaned from the academic references that you have consulted for your research. So logic is your main tool whenever you present an academic argument. The objective behind preparing this guide is to introduce you to the various factors that are involved in helping you become a successful student. It is providing you with an initial awareness by briefly outlining the skills that are required in writing. In other words, it is giving you a glimpse of what it means to become an academic writer. As you progress with your learning, you will be exposed to other details and finer points of the art of academic writing. A word of warning: writing essays for different disciplines or subject areas will require slightly different techniques. Areas of difference occur in the subject matter being researched, the points of view the disciplines take, the specific terminology being applied and the referencing styles. 1 This guide is generic, however; that is, the process it describes is applicable to academic writing irrespective of the discipline or subject area involved. It will take you through writing an essay in steps. In practice, however, all the steps are connected. Remember that essay writing is an individual process and you will develop the techniques that suit you best. The process of essay writing An academic essay is essentially a piece of writing which answers a question, presents a point of view in a clear and logical way and is supported by evidence from academic sources. In writing the essay, which is geared specifically to your discipline, you are coming to terms with new knowledge and demonstrating a wide range of skills. ‘To essay’ means ‘to try, to attempt’—it is intended to present a challenge. The process requires you to organise your thoughts clearly and to communicate these to a reader in an ordered way. In writing essays you are learning specifically through writing. It is a central learning process of many disciplines at university. Some of you will bring well-established and successful strategies to the essay writing process; others will not be so accustomed to the task. Although we recommend that you follow the steps in the order outlined in the accompanying diagram, no single set of rules about essay writing applies to everyone. Through experience you will develop other strategies that will suit you specifically. The process of essay writing 2 Step 1: Analysing the question ‘I have always preferred to reflect upon a problem before reading on it.’ (Jean Piaget) (a) Things to note immediately As soon as the essay topic is known you should ask yourself the following questions: • When is the due date? (Note the date in your diary and timetable the steps of essay writing in your diary also.) • How long is the essay? (This is your guide to how much reading you will need to do.) • What part of the course does the essay relate to? • What is the essential subject matter of the essay? • What do I already know about the topic? • How much research do I need to do? • What does the person who set the topic expect? These questions may seem very obvious, but they are in fact your starting point. Make sure you answer them and then keep them in mind throughout the whole essay writing process. Always go back to the essay question when the going gets tough! Keep it in mind all the time. (b) Deconstructing the question In order to answer an essay question properly, it is important to look carefully at what you are being asked to do. Breaking the topic into three types of words will help your understanding. • Content words are those that tell you the subject areas of the topic. • Limit words are those that tell you the scope or boundaries of the essay. • Direction words are those that tell you what to do with the topic. For example, examine the following essay question: Discuss direction the effects of the on Australia’s international reputation 2000 Olympic Games (2500 words) content limit In this essay question: • the content words are ‘the effects of the 2000 Olympic Games’ and ‘Australia’s international reputation’—they tell you the subject matter of the essay question; • the limit words are those that tell you the boundaries of the essay—‘2000 Olympic Games’ and ‘2500’words; and • ‘discuss’ is the direction word—it tells you what to do with the topic. Note that content and limit words are often interchangeable. 3 Here is a list of commonly used direction words and their definitions.1 analyse describe the main ideas and their relationships, assumptions and significance argue present the case for and/or against a particular proposition compare show the points for and against or the similarities and differences contrast to compare by focusing upon the differences criticise present your considered opinion based upon the points for and against the argument. Criticising does not necessarily mean condemning the idea. It is best to present a balanced argument showing both the positive and the negative points. In your conclusion you should state which side of the argument you agree with and your reasons for doing so. define present the meaning of the term, generally in a formalised way. Including an example will enhance your definition. describe present a detailed and accurate picture of the event or phenomenon discuss describe the event or phenomenon, but giving the positive and negative aspects. At university level, it would be fair to expect a critical discussion, citing the significance and assumptions, if relevant. In your conclusion state your point of view clearly, giving evidence for your opinion. enumerate list or specify and describe 1 evaluate weigh up or give your assessment of the relevant matter citing positive and negative features, advantages and disadvantages examine present in depth and investigate the implications explain make plain, interpret and account for in detail illustrate explain and make clear by the use of concrete examples, or by the use of a figure or diagram interpret present the meaning using examples and presenting your opinion with evidence to back up your statements justify present the basis for a particular event or phenomenon and explain why you think it is so. You need to present evidence to support your views and conclusions. outline give the main features or general principles of a subject, omitting minor details and emphasising structure and relationships Adapted from L. Marshall & F. Rowland, A Guide to Learning Independently, Longman, Melbourrne, 1989, p. 61. 4 Try out your skills with the following exercise. Topic analysis exercise Discuss the effects of Feng Shui ideas on Australian homes from 1990 to 2000. (1500 words) Using the above essay topic, divide it into its various parts: • Highlight the content words. • Circle the direction word. • Put square brackets around the limits of the topic. • Compare your answer with the one given below. Content words = ‘Feng Shui ideas’, ‘Australian homes’ Direction word = ‘discuss’ Limits = ‘Australian homes’, ‘1990 to 2000’, 1500 words (c) Brainstorming the question This is a vital stage. Brainstorming is a way of creatively generating ideas for your writing. To do this, take a pen and paper and write the topic on your sheet of paper. Then spend ten minutes jotting down all of the thoughts and associations that come to mind when you think of the topic. It is necessary to suspend all critical and evaluative thoughts from your mind as these will block your creative thoughts, so leave these until the second step in the process. The next step is to look critically at your ideas and thoughts and then select those that will be most useful for your essay. Try to make links between the points and ideas on the same sheet of paper. It is also useful to ask questions of your topic, such as ‘what, when, how, why, who, how significant and to what extent?’ as a way to generate more ideas. Categorise your ideas. Many students find it useful to make diagrams at this stage. Thinking in this way makes you aware of the gaps in your knowledge, what reading you have to do, what further questions you have to ask and answer. Brainstorming will help you to explore a topic or problem, and it can ‘kick-start’ your brain. It is often combined with an incubation period in which your subconscious will work on ideas. Study tip 1 Don’t forget to schedule this time into your diary. 5 (d) Making a preliminary plan for your research In this stage you should move from analysis and brainstorming to making an initial plan for the whole essay project. Use the material from the brainstorming step to form this outline. Depending on how much you already know about the topic, making a plan may require you to: • firm up your ideas about the topic (note that these could change as you do further research); • think about what aspects of the topic you need more information on; • remind yourself of what the essay is really asking; • assess essay reading lists and select the most relevant books and articles to obtain from the library; and • plan your time to meet the essay deadline. Preliminary planning exercise Discuss the effects of the 2000 Olympic Games on Australia’s international reputation. (2500 words) Use the above essay topic to draw up a preliminary plan. Preliminary plan 1 Define key words: ‘reputation’, ‘effects’. 2 Check lists of references provided in your study guide. 3 Research government publications and newspapers (Age and Australian) about the economic, social and cultural effects of the Olympics on Australia. 4 Check to see if any information kits exist. 5 Spend seven days on the research. Having these points in mind will give you a focus when you begin reading and making notes. Remember that planning is actually a continuous process which overlaps the other stages of essay production. 6 Step 2: Reading and making notes ‘I think best with a pencil in my hand.’ (Anne Morrow Lindbergh) In this stage of essay production, the research phase, it is vital that you always read and make notes with a purpose—with the essay question firmly in mind. The starting points for this stage are: • the essay question; • your unit study guides and readers; • reading lists; • lecture and tutorial notes; and • any advice from tutors and lecturers. (a) Reading Note that academic texts, such as books and journal articles, follow specific conventions. They usually use introductions, paragraphs and conclusions. Awareness of these parts can greatly facilitate your reading. Study tip 2: Previewing reading material Before you begin to read, it is useful to preview the book or journal article as a whole. An understanding of the structure will help you to identify the more relevant parts quickly. The introduction The introduction will introduce the topic in a general way. It will then provide a statement of the problem and outline the author’s intention and provide a framework for the article, chapter or book that you are reading. This is a key element in understanding what the author is writing about. The paragraph as an ‘idea unit’ Each paragraph of an article is internally coherent and forms a link in the continuity of the whole piece of writing. The main idea of the paragraph is usually presented in the topic sentence. Topic sentences are usually located at the beginning of a paragraph. The other sentences in the paragraph support, illustrate and expand on the main idea. You need to look for the topic sentences in your reading because they contain the main point of each paragraph. The conclusion This is where the author will summarise the ideas presented in the body of the article, chapter or book. This will be consistent with the introduction. The author may also comment on the significance of the work, which is key to your understanding of the reading material. 7 Signal words ‘Signal words’ tell the reader where the argument is going and show the transition from one point to another. They often occur in the topic sentence, but they can also be found throughout the essay where they serve to develop the argument between paragraphs and within paragraphs. These are very significant not only for your reading but for your writing as well. Signal words are words and phrases which show relationships between ideas, points or examples. Here is a list of the meanings and the words you can use to indicate these meanings. Signal words addition in addition, again, also, and, besides, further, furthermore, moreover, too, similarly. concession otherwise, admittedly, however, nevertheless, of course, after all, nonetheless, indeed. cause and effect accordingly, as a result, consequently, otherwise, therefore, thus, as a result, so, hence, as a consequence, thereupon. comparison similarly, likewise, in the same manner, also, as well as. conclusion in conclusion, to sum up, finally, lastly, to conclude, accordingly, overall. connections in time after a short time, afterwards, as long as, as soon as, at last, at length, at that time, at the same time, before, earlier, of late, immediately, in the meantime, lately, later, meanwhile, presently, shortly, since, soon, temporarily, thereafter, until, when, while. contrast in contrast, although, and yet, but, however, nevertheless, on the other hand, on the contrary, conversely, whereas, alternatively, in spite of. emphasis undoubtedly, indeed, true, above all, most important, the main point here is. examples or special features for example, for instance, in other words, in illustration, in this case, in particular, specifically, an example of this. qualification except for, admittedly, studies suggest that, perhaps, it would seem that, it tends to be the case that, may be, could be. sequencing firstly, secondly, lastly, finally, then too. 8 Skimming The most effective strategy for coping with the volume of reading is skimming. Skimming allows you to locate the most useful material which you will then read in detail and make notes from for your essay. You may need to skim a whole book to decide if it will be useful for your essay. Skim: • the title • back cover • contents page • chapter headings • first paragraph and concluding paragraph of each chapter • first sentence of paragraphs in chapters which look useful • the index. Skimming is a vital reading strategy for essay writing as it will give you an overall feel for the area you are writing about. Most importantly, it will help you find the reading which you really need to do, the reading from which you will make notes and use directly in the essay. (b) Making notes As we have seen, reading is an active task. Note making, similarly, keeps your attention focused and is a most effective way of committing information to memory. Make sure you read and take notes with the essay question firmly in mind. Making notes forces you to: • summarise a range of writers’ ideas and arguments; • select points relevant to your purpose; • understand and interpret the original source; • remember what you have read; and • continually clarify and adjust your perception of your essay topic in the light of your increasing understanding of the materials and arguments presented by others. Making notes is an important stage in the understanding of your topic. It is also the foundation of good writing. Your notes will provide the basis for your thinking and the materials for your essay. You will need to develop your own system of writing notes, whether this is done on paper or on a computer. However, the following is essential: • Make sure that you note all the bibliographical details of the books and articles you use in writing the essay: author, title, edition, publisher, place and year of publication, specific page number (for acknowledging authors’ points and quotations). • You need a flexible note-making system so that you can rearrange the notes for the purposes of the essay. Using loose-leaf paper or cards will help you to achieve this flexibility. • Leave wide margins on your note paper so that you can add comments or crossreferences which are crucial to your essay. 9 Study tip 3 Remember that reading and making notes must be done with the essay topic clearly in mind. Want to know more? See the handout on notemaking on the Academic Skills website http://www.deakin.edu.au/studentlife/academic_skills/undergraduate/handouts/notetaking.php 10 Step 3: Making essay plans ‘As the mind works the hand moves.’ (Fay Weldon) Planning an essay is essential in order to achieve a logical structure. Here is a diagram of what is meant by a logically structured essay. There are many ways of making essay plans, but here we will mention two. Essay structure 11 (a) Concept mapping ‘Concept mapping’ is suited to people who are comfortable with visual material. The idea is to represent your knowledge pictorially. This is done through drawing diagrams with connecting arrows to indicate the logical organisation of the material. The advantage of this is that you can clearly see what gaps there are in your research and fill them. Often you can see new connections in the material that may not have been obvious before. For example, the accompanying diagram is a possible concept map for the following essay topic. Discuss the effects of the 2000 Olympic Games on Australia’s international reputation (2500 words) 12 (b) Making a list The second method is to make a list, not unlike a shopping list. Firstly list all of the points and secondly categorise these points under sub-headings. These will become the sections of your essay which will contain the paragraphs. This approach enables you to see the logical flow of the essay very clearly. It provides a road map for your writing. Making a list exercise Discuss the effects of the 2000 Olympic Games on Australia’s international reputation. (2500 words) Use the above essay topic to draw up a list of the points to be made in the essay. Intro: primarily a positive effect. 1 increased tourist numbers—Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane 2 increased respect for Aust’s technological expertise 3 increased appreciation of Aust’s artistic achievements 4 broader understanding of indigenous issues 5 increased understanding of Aust society Conclusion: great increase in international awareness of Australia—positive, but the long-term economic effects are as yet unknown. Sources of evidence = Australian government reports, Internet, newspaper articles, journal articles. Try both of these methods or a combination. Essay plans function as your guide for the writing stages of the essay. A plan ensures that you keep on track and do not fill your essay with irrelevancies. 13 Step 4: Writing the essay ‘How do I know what I think until I see what I say?’ (E. M. Forster) This is perhaps the most exciting and challenging step because it involves putting all of your thinking, reading and note making together. Formulating your thoughts into writing is a craft that can be developed like most other skills. One principle of writing is knowing what you are going to say before you write. However, many of us think as we write; that is, the process of writing actually facilitates our thinking. So, instead of expecting the first draft to be perfect, be prepared to make several drafts of your plans as well as of your essays. Successful writers are those people who try out different versions of a sentence and then choose the one that suits them best. Try saying aloud what you mean. This strategy often works for those who have trouble formulating a sentence on paper. Study tip 4 Remember that essays use more formal language than everyday speech. Do not use colloquialisms—for example, ‘Johnnie gave it his best shot’ is not acceptable in a formal essay. Another key to successful writing is using predominantly short sentences. Make only one point per sentence and start a new one for the following point. This will avoid becoming entangled in a ‘web of words’. Expressing one thought per sentence makes it easier to construct sentences which follow logically from the previous ones. After you have achieved the logical ordering of points, then you can go back and link your sentences in a polished manner. Want to know more? See the resource on academic vocabulary on the Academic Skills website: http://www.deakin.edu.au/studentlife/academic_skills/downloads/Voc abulary.doc Remember that there is no place in an essay for irrelevant points. Keep the essay question and plan always at hand and pay careful attention to the points you are expressing and the order in which they are being made. You need always to be judging whether your points are irrelevant or making illogical leaps. In smoothing the transition from one paragraph to another, ‘signal words’ can help (see p. 8). (a) Essay structure—crafting the introduction, body and conclusion The introduction The introduction is very important because it is the first impression that the reader gets of 14 your work. It should provide the steps that lead the reader to a clear understanding of how you are going to answer the question. So the introduction must do several things. It must: • set the context for the topic in a general way so that after reading this section of the introduction the reader can say, ‘This essay will be generally about X’; 15 • become specific so that after reading this section, the reader can say, ‘This essay will be specifically about x’; and • ensure that the introduction relates directly to the question and if appropriate, the position you will argue will be outlined. The body Make sure when writing essays that each of your paragraphs has a clear topic sentence which carries the main idea of that paragraph. The rest of the paragraph should then relate to and support the topic sentence. Also ensure that you use ‘signal words’ throughout your essay to show the development of your argument, the connections between parts of the essay and the transition from one point to another. (A list of signal words is included on p. 8.) In the body of an essay each idea or argument listed in the introduction is examined—in the same order as listed—and developed. A typical paragraph which develops an argument has the following structure: • a topic sentence which: – conveys the main idea of the paragraph; and – is commonly found beginning a paragraph, though the position is variable. • example or supporting sentences which, using your research, provide examples or secondary arguments to support the topic sentence; and • a concluding sentence which restates the topic sentence by way of concluding and tying together the whole paragraph. The conclusion In the conclusion the main points or arguments made in the essay are summarised, and the major point of view is restated. Depending on what the essay topic is asking you to do, in your conclusion you may also have to: • evaluate the material you have presented; • indicate that you understand the significance of what you have argued; • state your conclusions; • forecast the future; and/or • make recommendations. Common problems and ways to fix them Inability to get started • Use the analysis/brainstorming material to write an introduction to get your ideas flowing. • Put pen to paper! If using a computer, switch it on! 16 Getting stuck part way through • Have a break. • Do more reading. • Check the analysis/brainstorming section of this guide. • Talk to a lecturer or another student (phone, email or online). Inadequate reading and note making • Do more reading. • Take more notes, keeping the essay topic in mind. • Organise your notes, references and bibliographic material carefully. Your argument is weak/goes sour/loses the thread • Rethink your argument. • Go back to where your argument was on track. • Go back to your plan. • Discuss your essay with another person. Running out of stamina • Devise your own strategies. These could include a ten-minute break in every hour to keep you alert. • Take more exercise, get regular sleep, eat regular meals, cut down your sugar and caffeine intake, eat more fruit. You know what is best for you! 17 Step 5: Editing ‘Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what one is saying.’ (John Updike) Editing is very important because you are aiming for a clear and accurate presentation. Editing the essay is an ongoing process. Many good writers go through a continual process of polishing their work. After you have completed your first draft put the essay away for at least a day and return to it with fresh eyes. This makes it much easier to spot gaps in the content, irrelevant material, flaws in the logical structure, repetition and lapses in expression. Editing should be done at least twice, concentrating each time on different aspects. (a) Editing for logic and coherence Logic means that there is one clear line of argument relating to one topic and that all the paragraphs and sentences connect to the question. The essay should, therefore, present a logical, well-developed and well-supported argument. To check that the essay is well structured, go through your essay and identify the topic sentences. Each should depict the main point of each paragraph. In your essay do all of the main points relate to the question? Is the argument well developed? Check the introduction, body and conclusion—does each part fulfil its role? Study tip 5 If you find a paragraph that lacks a topic sentence, now is the time to add one. To do so, ask yourself ‘what is the main point of this paragraph?’. The answer to this question will usually provide the topic sentence for which you are searching. ‘Coherence’ means that all parts of the essay are linked. As we have seen, a good way of ensuring a coherent argument is to use ‘signal words’ to show the development of the essay. Don’t be afraid to use them. They can appear at the beginning of a paragraph to signal a main idea and throughout a paragraph to link supporting information to that main idea. They are also used to signal the transition or change of ideas which occur between paragraphs, thus linking the whole essay together. (b) Editing for style and expression Style and expression refers to our choice of vocabulary, the way we construct our sentences, the way we introduce our ideas and develop our paragraphs. Most of us can improve our style by improving our expression. Good expression is clear and direct. It facilitates rather than hinders the reader. It leaves the reader satisfied. How can you achieve this? • Read your work aloud and listen to whether it makes sense. • Check that you have you used proper sentences. • Check whether you have used unnecessary words. • Check your sentence length—a long and convoluted sentence is difficult to understand because it is hard to follow. • If the sentence reaches three lines in length, you probably need to separate the ideas into two sentences. 18 (c) Editing for spelling, grammar and punctuation These technical aspects of the essay writing process are as important as all the other steps. • ‘Near enough’ is not good enough; marks are deducted for errors in spelling, grammar and punctuation. • Use doubt as your guide—if something does not look right, check it in a dictionary or with a friend. This stage involves proofreading which is discussed in the next section. Study tip 6 Computer spell checkers are useful tools but pick up only about 80% of errors, so do not rely on them. Similarly, grammar checkers are often inaccurate and should not be relied on. Always consult a dictionary when in doubt. (d) Proofreading Proofreading is usually the final step in the editing process. The aim is to produce an errorfree essay thus careful checking for mistakes in spelling, punctuation and typing is essential. Consult the relevant unit style guide for guidance on margins, spacing and referencing. Study tip 7 Proofread on a printed copy (use double spacing). This makes errors easier to spot. Study tip 8 Read your text aloud to another person to check for errors. Use a ruler to help you to look at each word, letter and punctuation mark very closely. After checking your citation of sources (see below) print out your final copy. Photocopy the essay or keep a backup copy on disk. Want to know more? Consult the resource ‘Editing’ on the Academic Skills website http://www.deakin.edu.au/studentlife/academic_skills/undergraduate/ handouts/editing.php 19 Step 6: Citing your sources (a) Plagiarism Most academic work builds on what has gone before and you will be using academic research as the basis for your essays. It is necessary, however, to acknowledge others’ work when you use it. Any academic writing is acknowledged as the intellectual property of its creator. That is, the creator owns the idea and to use it without acknowledgment is seen as theft. Writing academic essays always involves the citing of sources and the inclusion of reference lists. Therefore you must acknowledge the original owner of the idea when you quote directly, summarise or paraphrase points from other works. The failure to acknowledge another’s work and thus claim it as your own is plagiarism. It is a form of cheating and is a serious offence at university. Strict penalties apply. Sometimes plagiarism is unintentional. Students may read for an essay and take detailed notes which find their way into the essay without a reference. To avoid this you must take great care when making notes to ensure that the sources of all your information are clear and accurate. As a general rule, you should aim to write in your own words and keep quotations to a minimum. (b) Referencing styles—Harvard and Oxford If you quote directly from or summarise another’s work, you must cite your source. Here we will outline the two systems most commonly used at Deakin to cite sources: the Harvard and the Oxford systems. Each School at Deakin University has its own particular style of citing sources, and these reflect the different conventions of the relevant academic disciplines. For more complete instructions for citing sources, consult the style or unit guide for your particular discipline. Refer to these or your lecturer for the specific requirements of your units. The Harvard (Author–Date) system is usually used for science and technology, psychology, geography, sociology, commerce and other disciplines, while the Oxford (Note) system is often used for law, history and philosophy. The Harvard system Here is a fictitious passage using the Harvard system: Studying at university is very different from studying at school. A survey of students in three disciplines at Gondwana University found that 75% of first-year students felt pressured by the number of essays they had to complete to satisfy the unit requirements (McPherson 1992, p. 7). According to Gartlan (1993, p. 5), this finding is not unusual in Australia, and it accords with some evidence from overseas, too (Loney 1990, p. 170). Not all countries record the same result, however (see Loney 1990, p. 173), and some Australian universities produce startlingly different figures (Gartlan 1993, p. 5). McPherson (1992, p. 6) also found that students at university had less contact with their teachers than they had at school. As you can see here there are three pieces of information that are cited in the text, usually in brackets. These are the author’s family name, the date of publication and the page number. Note that if the author’s name is already part of the sentence, it can be left out of the bracket, as in the third sentence in the quotation above. 20 A list of references is then included at the end of the essay and would include: References Gartlan, P. 1993, ‘Do universities work students too hard?’, Herald, 3 September, p. 5. Loney, A. 1990, Education in Britain Today, Macmillan, London. McPherson, J. 1992, ‘The differences between studying at university and studying at school’, Education Today, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 5–10. The reference list should list all the works cited in the essay and no works that are not cited. The Oxford system The fictitious passage below uses the Oxford system of citation: Studying at university is very different from studying at school. A survey of students in three disciplines at Gondwana University found that 75% of first-year students felt pressured by the number of essays they had to complete to satisfy the unit requirements. 1 According to Gartlan, this finding is not unusual in Australia, 2 and it accords with some evidence from overseas, too.3 Not all countries record the same result, however,4 and some Australian universities produce startlingly different figures. 5 McPherson also found that students at university had less contact with their teachers than they had at school. 6 The footnotes accompanying this passage, placed at the bottom of the page, would be: 1 J. McPherson, ‘The differences between studying at university and studying at school’, Education Today, vol. 6, no. 3, 1992, p. 7. 2 P. Gartlan, ‘Do universities work students too hard?’, Herald, 3 September 1993, p. 5. 3 A. Loney, Education in Britain Today, Macmillan, London, 1990, p. 170. 4 ibid., p. 173. 5 Gartlan, loc. cit. 6 McPherson, op. cit., p. 6. Note the following points: • The author’s initials are given first, followed by the family name. • When a work is cited twice in succession, only ‘ibid.’ (short for ibidem, meaning ‘in the same work’), plus the new page number, is needed. • When a work is cited more than once, but not immediately following the previous citation to it, the second and subsequent citations give the author’s family name, followed by ‘op. cit.’ (short for opere citato, meaning ‘in the work cited’) and the different page numbers. • When the same page in a work is cited more than once, the second and subsequent citations give the author’s family name, followed by ‘loc. cit.’ (short for loco citato, meaning ‘in the place cited’). Note that when using the Oxford system of citation it is becoming increasingly common to dispense with the Latin tags ‘ibid.’, etc. and in their place to use a shortened form of the original citation for second and subsequent citations. When using this form of the Oxford system, footnotes 4, 5 and 6 above would be as follows: 4 Loney, p. 173. 5 Gartlan, p. 5. 6 McPherson, p. 6. If more than one work by an author is cited, second and subsequent citations need a shortened form of the title, as well as the author’s family name. 21 (c) Bibliographies In addition to citing the sources of material created by others, you need to include a bibliography at the end of your work. A bibliography lists all of the works that have contributed to the preparation of the essay, whether cited or not in the essay. A bibliography is arranged alphabetically by authors’ family names, and the elements in each entry are given in a similar way as for footnotes in the Oxford system. For example: Gartlan, P., ‘Do universities work students too hard?’, Herald, 3 September 1993. Loney, A., Education in Britain Today, Macmillan, London, 1990. McPherson, J., ‘The differences between studying at university and studying at school’, Education Today, vol. 6, no. 3, 1992. For further details of the precise form in which to set out the entries in a bibliography, consult your unit style guides. (d) Citing electronic sources Students are increasingly using information from sources such as the Internet, CD-ROMs, films or television programs in their research. These sources must be cited in such a way that readers can retrieve the material that has been cited, just as with printed material. There are a number of approaches and styles available when citing non-print sources, just as there are different styles such as the Harvard, Oxford, American Psychological Association used by different disciplines to cite printed materials, and you should consult your unit style guide for detailed instructions. This guide provides instruction and examples of how to cite online sources in a form consistent with the Harvard style used in this guide.2 Online material In the text, the citation for online material includes the family name(s) of the author(s) or the name of the ‘authoring’ organisation, and the document date or date of last revision (which may require the date and the month, as well as the year). For example: Australian Bureau of Statistics (1997) White (29 June 1997) In the reference list, the date you accessed the material should be included because online material may be continually updated or revised so you cannot be sure that it will not have been changed since the time you consulted it. For example: Australian Bureau of Statistics 1997, ‘Key national indicators’, ABS Statsite, http://www.abs.gov.au/ (accessed 26 June 1997). White, D. E. 29 June 1997, ‘ “The god deified”: Mary Shelley’s “Valperga”, Italy and the aesthetic of desire’, Romanticism on the Net, vol. 6, May 1997, http://users.ox.ac.uk/~scat0385/valperga.html (accessed 2 July 1997). 2 More detailed explanation and examples of other non-print citations can be found in Publishing Manual: Essentials of Preparing Course Materials, rev. edn, Deakin University, Geelong, Vic., 1998. www.deakin.edu.au/learningservices/resources/pub_manual/index.php 22 23 Conclusion Essay writing is complex as it involves a wide range of skills. These skills will continue to develop throughout your time at university. Continual practice will ensure that you will be able to handle the more sophisticated tasks that are required at a higher level. Here are some final hints to take away with you. • Always consult your unit guide about the specific requirements. • Stay focused on the question. • If you are confused, seek clarification from the relevant academic. • Further assistance is available from the Academic Skills Advisers on each campus and online on the Academic Skills website at: www.deakin.edu.au/academic_skills/ • You can always discuss essay topics with other students in person or online through the study success discussion forum on the Learners Guide at: www.deakin.edu.au/dso/ • You can access and download learning support materials from the Resource Room at: www.deakin.edu.au/studentlife/academic_skills/resource_room/index.php You have now completed reading about the essay writing process. The test of this guide’s effectiveness, and of how well you have comprehended it, will be in applying this knowledge to your next essay or assignment. Try consciously to use all of the steps. We invite you to let us know whether the guide made a difference to you. Please fill in and send us the feedback sheet on the last page of this guide. 24 Further reading Texts on academic writing Bailey, R. 1984, A Survival Kit for Writing English, 2nd edn, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne. Bate, D. & Sharpe, P. 1990, Student Writer’s Handbook: How to Write Better Essays, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Sydney. Chesterman, Simon & Rhoden, Clare 1999, Studying Law at Uuniversity: Everything You Need to Know, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Clanchy, B. & Ballard, B. 1997, Essay Writing for Students—A Practical Guide, 3rd edn, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne. Creme, Phyllis 1997, Writing at University: A Guide for Students, Open University Press, Buckingham, England. Davis, Lloyd 1996, Structures and Strategies: An Introduction to Academic Writing, Macmillan Education Australia, South Melbourne. De Fazio, Teresa 1998, Studying in Australia: A Guide for International Students, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Essay Writing Made Easy [videorecording] 1996, Deakin University, Geelong, Vic. Germov, John 1996, Get Great Marks for Your Essays, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Hay, Iain 1997, Making the Grade: A Guide to Successful Communication and Study, Oxford University Press, Melbourne. Marshall, L. & Rowland, F. 1993, A Guide to Learning Independently, 2nd edn, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne. McClain, Molly 1998, Schaum’s Quick Guide to Writing Great Essays, McGraw-Hill, New York. McLean, Patricia & Tatnall, Arthur 2000, Studying Business at University, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Orr, Fred 1992, Study Skills for Successful Student, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Petelin, R. & Durham, M. 1992, The Professional Writing Guide: Writing Well and Knowing Why, Longman Professional, Melbourne. Rhoden, Clare 1998, Studying Science at University: Everything You Need to Know, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Wallace, Andrew 1999, Beginning University: Thinking, Researching and Writing for Success, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Windschuttle, K. & Windschuttle, E. 1998, Writing, Researching, Communicating: Communication Skills for the Information Age, McGraw-Hill, Sydney. Deakin University style manuals Faculty of Arts 2003, Assignment Preparation and Style Guide, Deakin University, Geelong. Faculty of Education 2003, General Information on Assignments, and a Guide on Style, rev. edn, Deakin University, Geelong. (http://www.deakin.edu.au/education/RADS/resources.php) School of Nursing 1998, Study Skills and Style Guide for Assignment/Thesis Writing, Deakin University, Geelong. Dictionaries and editorial style manuals The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English 1990, 8th edn, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Macquarie Dictionary 1991, 2nd edn, Macquarie Library, Sydney. Roget’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases 1987, new edn, Penguin, London. The Chicago Manual of Style: For Authors, Editors and Copywriters 1982, 13th edn, Chicago University Press, Chicago. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association 2001, 5th ed, American Psychological Association, Washington DC. 25 Essay structure exercise Here is a practical exercise which will clarify your understanding of essay structure. 1 Read the sample essay to gain an overview. 2 Work though the tasks listed after the essay, using the essay as your resource. You will need to extract sentences from the essay and write them in the appropriate places. Sample essay ‘An essay is essentially a written argument.’ Discuss in terms of the implications for students and lecturers. Of all the tasks that tertiary students encounter, writing essays seems to be the most stressful and cause the most difficulties. Much of this is due to uncertainty about what an essay is and what role it plays in a tertiary course. This essay will support the view that the essay is essentially a form of written argument. The cultural and educational background to this view will be briefly explained. The main implications of this view for both students and lecturers will then be examined within the context of tertiary study. An essay can be defined as a short piece of prose writing on any one subject. An argument is a reasoned discussion in which reasons are put forward in support of and against a proposition, proposal or case. In the case of the essay at tertiary level, the student’s ability to present a well-reasoned, well-supported argument is the main way in which a lecturer assesses a student’s progress in most courses of study. It is important to look at the cultural and educational background to understand how important the concept of argument is in our society. The ancient Greeks valued oratory and rhetoric and, in particular, the ability to argue and to persuade others to a point of view (Horton 1985, p. 32). This oratorical ability gradually became important in the written system as well. This can be seen in philosophical writings throughout history. Argument has also played a fundamental role in the parliamentary system of debate. The education system also values the ability to express one’s opinion, to argue logically, to counter another person’s argument. In primary and secondary school there is an emphasis on basic knowledge, but in late secondary school and the early years of university there is a shift in direction to a more analytical and critical approach to learning. At this stage students are encouraged to question, evaluate and begin to think independently about the topics they are studying. In the final years of tertiary study the student is encouraged to speculate, to hypothesise, to search for new evidence, to develop individual opinions or theses and to support these viewpoints. The essay is a key way of assessing the ability to argue a point and to synthesise what has been read into a reasoned argument. An essay shows a student’s ability to analyse a range of ideas and evidence from sources, to assess these ideas and evidence and form an opinion about them, and to justify that opinion. Lecturers require students to show their thinking through essays (Bate & Sharpe 1996, p. x). 26 Another important point is that this cultural and educational background has influenced the way in which an argument is presented. Our society places value on an argument which, generally speaking, has a linear pattern. This linear pattern makes the line of argument clear to the listener or reader. ‘Linear’ in this context means ‘logical’. Thoughts should be connected together, and all ideas should relate to the main point of the essay. Connections between sentences and between paragraphs should be obvious, and the overall structure should be clear. This preference for linear argument is reflected in the way an essay is organised. The conventional essay structure allows for a linear, logical presentation of an argument, with an introduction, the body of the essay and a conclusion. Using this structure, in the introduction the topic is introduced in a general way, terms are defined, the specific areas that will be covered are named, and the argument or viewpoint to be put forward in the essay is stated. The body of the essay develops and supports each idea or argument listed in the introduction. Each idea or argument is contained in a paragraph which has a topic sentence containing the main idea. A concluding statement in the body restates the main points—usually, but not always, in the topic sentences—and ties them all together and relates them back to the main argument of the essay. The conclusion summarises the main ideas or argument of the essay and may also evaluate the material presented; it may present the author’s view and/or make recommendations. If an essay is essentially a written argument, what are the implications for students at tertiary level? Students are confronted with many essays where they are expected to write an argument which is convincing and supported by evidence relevant to their thesis. The main implication is that students must learn the linear way of presenting an argument. This linear presentation can be summed up in three words: introduction, body and conclusion. Students must become aware of this way of presenting an essay and must practise and refine it in order to cope with the load of essay writing with which they are inevitably confronted. The idea of linear progression extends throughout the whole of the essay. Each paragraph should flow logically from the previous one, and each sentence should build upon the preceding one. These are the implications for students, but what are the implications for the lecturer? As the essay is essentially a written argument, lecturers expect that essays will be relevant to the argument at hand, that they will use written sources from a wide and critical reading, and that they will contain reasoned and logical arguments (Wallace, Schirato & Bright 1999, p. 49). The lecturer, then, is in the best position to help the student move towards fulfilling these expectations. The lecturer is the expert in a particular area and must provide a model for the thought processes, style of argument and writing conventions which characterise a particular area of study or discipline. This is the case whether it is an argument in theology or sociology or a scientific report in physiology. Being the expert carries with it the responsibility of initiating students into the academic discourse of a particular area. Some students, through observation of lecturers and careful examination of the style of writing in the area, quickly pick up the rules. Other students need more assistance, and there are a number of things that lecturers can do to assist. 27 They can show their own thought processes and strategies in their writing. This can provide a model for students of how an argument is built up and supported and how controversial issues are approached. In addition, lecturers can demonstrate how texts in their subject area are typically constructed and how key elements can be identified. For example, in introductions to essays topic sentences can be identified, or in scientific papers the statement of hypotheses can be highlighted. A further helpful activity is where a lecturer takes students through examples of previous successful essays showing what he or she really wants from essays and highlighting the ways in which the writer structured and organised his or her ideas and argument. For off-campus students, these features should be built into the study guides. In conclusion, it can be seen that the essay is essentially a written argument in which students show a number of skills. These are that they have understood the question and adopted a viewpoint on it, have argued clearly and logically in favour of that viewpoint, and have supported it with evidence obtained from a range of sources. They should also express some original ideas and critical thought. Students have to learn the skills involved in writing essays and, of course, practise those skills with the guidance of lecturers, the experts in the styles of argument of particular academic disciplines. References Bate, D. & Sharpe, P. 1996, Writer’s Handbook, Harcourt Brace, Marrickvale, NSW. Horton, C. 1985, Ancient Greeks, Hamish Hamilton, London. Wallace, A., Schirato, T. & Bright, P. 1999, Beginning University, Thinking, Researching and Writing for Success, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW. Now fill in the blanks. Introduction 1 Using the sample essay, find an interesting general statement that shows the importance of the topic. Write the sentence here. 2 Find a statement that addresses the question and outlines the position the author is going to take. Write the sentence here. 28 3 What are the intentions in this essay? (2 sentences) Write the sentences here. Body The number of paragraphs in the body depends on the word limit of the essay. For this exercise analyse the first five paragraphs of the body of the essay. Paragraph 1 1 Find a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of this paragraph. Write the sentence here. 2 Find a few sentences that discuss the main idea of this same paragraph. This can be done through discussion, citation, examples, statistics, data etc. Write the sentences here. 3 Find a concluding statement that sums up the main idea of this paragraph. Write the sentence here. 29 Paragraph 2 1 Find a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of this paragraph. 2 Find a few sentences that discuss the main idea of this paragraph. This can be done through discussion, citation, examples, statistics, data etc. 3 Find a concluding statement that sums up the main idea of this paragraph. Paragraph 3 1 Find a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of this paragraph. 2 Find a few sentences that discuss the main idea of this paragraph. This can be done through discussion, citation, examples, statistics, data etc. 30 3 Find a concluding statement that sums up the main idea of this paragraph. Paragraph 4 1 Find a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of this paragraph. 2 Find a few sentences that discuss the main idea of this paragraph. This can be done through discussion, citation, examples, statistics, data etc. 3 Find a concluding statement that sums up the main idea of this paragraph. Paragraph 5 1 Find a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of this paragraph. 2 Find a few sentences that discuss the main idea of this paragraph. This can be done through discussion, citation, examples, statistics, data etc. 31 3 Find a concluding statement that sums up the main idea of this paragraph. Conclusion 1 The conclusion should present a summary of the main points used in the body of the essay. Find these sentences. 2 They should also show the relationship to the topic of the essay. 3 The final sentences should evaluate the points and show their importance to the topic. We hope this exercise has demonstrated the importance of logical structure in academic essay writing. Best wishes for your studies. 32 Feedback In order for us to improve this guide, please answer the following questions and return this sheet to the Academic Skills Adviser, Division of Student Life, Deakin University, Geelong, 3217. Thank you! Yes No 1 This guide clarified the essay writing process. [ ] [ ] 2 It assisted me with: Analysing a topic [ ] [ ] Brainstorming [ ] [ ] Reading [ ] [ ] Planning [ ] [ ] Writing [ ] [ ] Editing [ ] [ ] Proofreading [ ] [ ] Referencing [ ] [ ] All of the above [ ] [ ] None of the above [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] 3 Did you find the sample essay exercise valuable? 4 Before working through this guide, I rated my essay writing skills as: [ ] Poor [ ] Dodgy [ ] Good [ ] Excellent 5 After applying the advice in this Guide to my assessment essays, I found my essays had: [ ] Improved [ ] Stayed the same [ ] Worsened 6 Here are my suggestions and comments for improving the guide: