Plasma Physics Textbook: Introduction & Single-Particle Motions

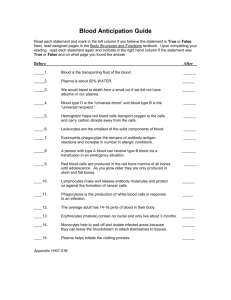

advertisement