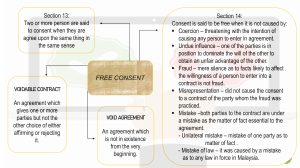

Obligations and Contracts Contracts – Nature and Concepts Coverage Atty. Joselito V. Abuel Juris Doctor (JD) Certified Public Accountant (CPA) Master in Business Administration (MBA) Licensed Professional Teacher (LPT) Data Protection Officer (DPO) LAW ON CONTRACTS Laws, Principles & Jurisprudence TITLE 2 – CONTRACTS Chapter 1 – General Provisions Chapter 2 – Essential Requisites of Contracts General Provisions Section 1 – Consent Section 2 – Objects of Contracts Section 3 – Cause of Contracts TITLE 2 – CONTRACTS Chapter 3 – Form of Contracts Chapter 4 – Reformation of Instruments Chapter 5 – Interpretation of Contracts Chapter 6 – Rescissible Contracts Chapter 7 – Voidable Contracts Chapter 8 – Unenforceable Contracts Chapter 9 – Void or Inexistent Contracts Title II. - CONTRACTS CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS Art. 1305. A contract is a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. (1254a) Art. 1306. The contracting parties may establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy. (1255a) CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS According to their relation to other contracts: 1. Preparatory Those which for their object the establishment of a condition in law which is necessary as a preliminary step towards the celebration of another subsequent contract. Example: Contract of Partnership, Contract of Agency 2. Principal Those which can subsist independently from other contracts and whose purpose can be fulfilled by themselves. Example: Contract of Sale, Contract of Lease 3. Accessory Those which can exist only as a consequence of, or in relation with, another prior contract. Examples: Contract of Pledge, Contract of Mortgage CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS According to their perfection Those which are perfected by the mere agreement of the parties. 1. Consensual Example: Contract of Sale, Contract of Lease Those which require not only the consent of the parties for their perfection, but also the delivery of the object by any one party to 2. Real the other. Examples: Contract of Commodatum, Contract of Deposit, Pledge CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS According to their cause 1. Onerous Those in which each of the parties aspires to procure for himself a benefit through the giving of an equivalent or compensation. Example: Contract of Sale 2. Gratuitous Those in which one of the parties proposes to give to the other benefit without any equivalent or compensation. Example: Contract of Commodatum CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS According to risk involve 1. Commutative Those where each of the parties acquires an equivalent of his prestation and such equivalent is pecuniarily appreciable and already determined from the moment of the celebration of the contract. Example: Contract of Lease 2. Aleatory Those where each of the parties has to account the acquisition of an equivalent of his prestation, but such equivalent although pecuniarily appreciable, is not yet determined, at the moment of the celebration of the contract, since it depends upon the happening of an uncertain event, thus charging the parties with the risk of loss or gain. Example: Insurance Contract CLASSIFICATION OF CONTRACTS According to their names or norms regulating them 1. Nominate Those which have their own individuality and are regulated by special provision of law. Example: Contract of Sale, Contract of Lease 2. Innominate Those which lack individuality and are not regulated by special provision of law. Example: MOA, MOU which is not regulated by a special provision of law. CONTRACT OF ADHESION AUTONOMY OF CONTRACTS Is a contract whereby almost all of its provisions are drafted by one party. The participation of the other party is limited to affixing his signature or his “adhesion” to the contract. For this reason, contracts of adhesion are strictly construed against the party who drafted it. In Abe v. Foster Wheeler Corp, the Supreme Court held that the freedom to contract is not absolute. The same is understood to be subject to reasonable legislative regulation aimed at the promotion of public health, morals, safety and welfare. One such legislative regulation is found in Article 1306 of the Civil Code which allows the contracting parties to “establish such stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. It is erroneous, however, to conclude that contracts of adhesion are invalid per se. They are, in the contrary, as binding as ordinary contracts. A party is in reality free to accept or reject it. A contract of adhesion becomes void only when the dominant party takes advantage of the weakness of the other party, completely depriving the latter of the opportunity to bargain on equal footing. Art. 1307. Innominate contracts shall be regulated by the stipulations of the parties, by the provisions of Titles I and II of this Book, by the rules governing the most analogous nominate contracts, and by the customs of the place. (n) Art. 1308. The contract must bind both contracting parties; its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them. (1256a) (MUTUALITY) Art. 1309. The determination of the performance may be left to a third person, whose decision shall not be binding until it has been made known to both contracting parties. (n) INNOMINATE CONTRACT Those with lack individuality and are not regulated by special provision of law 1. 2. 3. 4. Do ut des – I give that you give Do ut facias – I give that you do Facio ut des – I do that you give Facio ut facias – I do that you do. RULES ON INNOMINATE CONTRACTS 1. Stipulations of the parties 2. The provisions of the Civil Code on obligations and contracts 3. The rules governing the most analogous nominate contracts; and 4. The customs of the place 1308 – Notes 1308 expresses what is known in law as the principle of mutuality of contracts. PURPOSE OF MUTUALITY OF CONTRACTS – the ultimate purpose is thus to nullify a contract containing a condition which makes its fulfillment or pre-termination dependent exclusively upon the uncontrolled will of one of the contracting parties. Art. 1310. The determination shall not be obligatory if it is evidently inequitable. In such case, the courts shall decide what is equitable under the circumstances. (n) Art. 1311. Contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs, except in case where the rights and obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. The heir is not liable beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent. (RELATIVITY) If a contract should contain some stipulation in favor of a third person, he may demand its fulfillment provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. A mere incidental benefit or interest of a person is not sufficient. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person. (1257a) 1311 – Note: Refer to Relativity of Contracts GENERAL RULE: Contracts take effect only between the parties, their assigns and heirs. EXCEPTIONS: 1. Contracts are not transmissible by their nature; or 2. Contracts are not transmissible by stipulation; or 3. Contracts are not transmissible by provision of law FOUR EXCEPTIONAL CASES TO THE PRINCIPLE OF RELATIVITY OF CONTRACTS 1. If a contract should contain some stipulation in favor of a third person, he may demand its fulfillment provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before it revocation.(1311) 2. In contracts creating real rights, third person who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby. (1312) 3. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them. (1313) 4. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. (1314) 1311 - Notes REQUISITES OF STIPULATION FOR AUTRUI 1. There must be a stipulation in favor of a third party 2. The stipulation must be a part not the whole, of the contract. 3. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person, not a mere incidental benefit or interest. 4. The third person must have communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation, and 5. Neither of the contracting parties bears the legal representation or authorization of the third party. 1312 and 1313- 1314 Note THIS IS AN EXCEPTION TO THE PRINCIPLE OF RELATIVITY OF CONTRACTS Art. 1312. In contracts creating real rights, third persons who come into possession of the object of the contract are bound thereby, subject to the provisions of the Mortgage Law and the Land Registration Laws. (n) Art. 1313. Creditors are protected in cases of contracts intended to defraud them. (n) Art. 1314. Any third person who induces another to violate his contract shall be liable for damages to the other contracting party. (n) (TORT INTERFERENCE) Art. 1315. Contracts are perfected by mere consent, and from that moment the parties are bound not only to the fulfillment of what has been expressly stipulated but also to all the consequences which, according to their nature, may be in keeping with good faith, usage and law. (1258) E X C E P T I O N 1314 - Note WHAT IS TORT INTERFERENCE? Article 1314 expresses the principle of tort interference. This is an exception to the principle of relativity of contracts. The tort recognized in this provision is known as interference with contractual relations. The interference is penalized because it violates the property rights of a party in a contract to reap the benefits that should result therefrom. ELEMENTS OF TORT INTERFERENCE 1. Existence of a valid contract. It must be duly established 2. Knowledge on the part of the third person of the existence of a contract. Requires that there be knowledge on the part of the interferer that the contract exists. 3. Interference of the third person is without legal justification. 1315 - Notes STAGES IN THE LIFE OF A CONTRACT Begins from the time the prospective contracting parties manifest their interest in the contract and ends at the moment of agreement of the parties. 1. Preparation or Negotiation Negotiation is formally initiated by an offer. Accordingly, an offer that is not accepted, either expressly or impliedly, precludes the existence of consent, which is one of the essential elements of a contract. 2. Perfection or Birth Takes place when the parties agree upon the essential elements of the contract. 3. Consummation The parties fulfill or perform the terms agreed upon in the contract culminating in its extinguishment. Art. 1316. Real contracts, such as deposit, pledge and commodatum, are not perfected until the delivery of the object of the obligation. (n) Art. 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. (1259a) Consensual Contract Those which are perfected by the mere agreement of the parties. Real Contract Those which require not only consent of the parties for their perfection, but also the delivery of the object by any one of the party to the other. Example: Sale or Lease Examples: Commodatum, Deposit, Pledge Formal/Solemn Contract When the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable or that a contract be proved in certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. Example: Donation of personal property exceeding P5,000; Immovable property in public instrument. Commodatum Deposit Pledge One of the parties deliver to another, either something not consumable so that the latter may use the same for a certain time and return it, in which case the contract is called commodatum. A deposit is construed from the moment a person receives thing belonging to another, with the obligation of safely keeping it and of returning the same. In a contract of pledge, the creditor is given the right to retain his debtor’s movable property in his possession, or in that of a third person to whom it has been delivered, until the debt is paid. Art. 1317. No one may contract in the name of another without being authorized by the latter, or unless he has by law a right to represent him. A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable, unless it is ratified, expressly or impliedly, by the person on whose behalf it has been executed, before it is revoked by the other contracting party. (1259a) GENERAL RULE No one may contract in the name of another EXCEPTIONS: 1. The person entering into a contract in the name of another has been authorized by the latter. 2. The person entering into a contract in the name of another has by law has a right to represent him. EFFECT OF AN UNAUTHORIZED CONTRACT GENERAL RULE: A contract entered into in the name of another by one who has no authority or legal representation, or who has acted beyond his powers, shall be unenforceable. CHAPTER 2 ESSENTIAL REQUISITES OF CONTRACTS GENERAL PROVISIONS Art. 1318. There is no contract unless the following requisites concur: (1) CONSENT of the contracting parties; (2) OBJECT certain which is the subject matter of the contract; (3) CAUSE of the obligation which is established. (1261) Essential Elements Natural Elements Accidental Elements The essential elements are those without which there can be no contract. Subdivided into: a. Common (Comunes) are those which are present in all contracts. Example: Consent, Object, Certain and cause b. Special (especiales) are present only in certain contracts. Example: Delivery in real contracts, form of solemn contracts c. Extraordinary or peculiar (especialisimos) are those which are peculiar to a specific contract. Example: Price Are those which are derived from the nature of the contract and ordinarily accompany the same. They are presumed by the law, although they can be excluded by the contracting parties if they so desire. Thus, warranty against eviction is implied in a contract of sale, although the contracting parties may increase, diminish or even suppress it. The accidental elements are those which exists only when the parties expressly provide for them for the purpose of limiting or modifying the normal effects of the contract. Examples of these are conditions, terms and modes. SECTION 1. - Consent Art. 1319. Consent is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract. The offer must be certain and the acceptance absolute. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. Acceptance made by letter or telegram does not bind the offerer except from the time it came to his knowledge. The contract, in such a case, is presumed to have been entered into in the place where the offer was made. (1262a) Art. 1320. An acceptance may be express or implied. (n) Art. 1321. The person making the offer may fix the time, place, and manner of acceptance, all of which must be complied with. (n) Art. 1322. An offer made through an agent is accepted from the time acceptance is communicated to him. (n) Art. 1323. An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before acceptance is conveyed. (n) Art. 1324. When the offerer has allowed the offeree a certain period to accept, the offer may be withdrawn at any time before acceptance by communicating such withdrawal, except when the option is founded upon a consideration, as something paid or promised. (n) CONSENT POLICITACION Is manifested by the meeting of the offer and the acceptance upon the thing and the cause which are to constitute the contract An imperfect promise (policitacion) is merely an offer. An imperfect promise that could not be considered a binding commitment. OFFER An offer is a unilateral proposition made by one party to another for the celebration of a contract. For an offer to be certain, a contract must come into existence by the mere acceptance of the offer without any further act on the offeror’s part. The offer must be definite, complete and intentional. Spouses Paderes vs Court of Appeals “There is an offer” in the context of Article 1319 only if the contract can come into existence by the mere acceptance of the offeree, without any further act on the part of the offeror. Hence, the ‘offer’ must be definite, complete and intentional. COUNTER-OFFER This refers to qualified acceptance NOTE: where the parties merely exchanged offers and counter-offers, no agreement or contract is perfected. Acceptance by Letter or Telegram Acceptance made by letter or telegram does not bind the offerer except from the time it came to his knowledge. 1321- Note The offerer may fix the time, place, and manner of acceptance, all of which must be complied with. A qualified acceptance constitutes a counter-offer. CONSENT OF CORPORATION It cannot act except through Board of Directors as a collective body, which is vested with the power and responsibility to decide whether the corporation should enter into a contract that will bind the corporation, subject to the articles of incorporation, by-laws or relevant provisions of law. 1322 - Note CONTRACT OF AGENCY By the contract of agency a person binds himself to render some service or to do something in representation or on behalf of another, with the consent or authority of the letter. BASIS The basis for agency is representation that is, the agent acts for and on behalf of the principal on matters within the scope of his authority and said acts have the same legal effect as if they were personally executed by the principal. 1323 - Note RATIONALE An offer becomes ineffective upon the death, civil interdiction, insanity, or insolvency of either party before acceptance is conveyed. The reason for this is that: The contract is not perfected except by the concurrence of two wills which exist and continue until the moment that they occur. The contract is not yet perfected at any time before acceptance is conveyed; hence, the disappearance of either party or his loss of capacity before perfection prevents the contractual tie from being formed. 1324 - Notes OPTION Is a contract granting a privilege to buy or sell at a determined price within an agreed time. An OPTION is a preparatory contract in which one party grants to another, for a fixed period and at a determined price, the privilege to buy or sell, or to decide whether or not to enter into a principal contract with any other person during the period designated, and within that period, to enter into such contract with the one to whom the option was granted, if the latter should decide to use the option. 1324 - Notes RULES AS TO OFFER 1. If the period is not founded upon or supported by a consideration, the offeror is still free and has the right to WITHDRAW the offer before its acceptance, or, if an acceptance has been made, before offeror’s coming to know of such fact, by communicating that withdrawal to the offeree. 2. If the period has a separate consideration, a contract of ‘option’ is deemed perfected, and it would be a breach of that contract to withdraw the offer during the agreed period. The option, however, is an INDEPENDENT contract by itself, and is to be distinguished from the projected main agreement which is obviously yet to be concluded. 1325 - Notes GENERAL RULE Business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. EXCEPTION If the business advertisements of things for sale appears to be a definite offer. 1326 – Note Advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals, and the advertiser is not bound to accept the highest or lowest bidder, unless the contrary appears. Art. 1325. Unless it appears otherwise, business advertisements of things for sale are not definite offers, but mere invitations to make an offer. (n) Art. 1326. Advertisements for bidders are simply invitations to make proposals, and the advertiser is not bound to accept the highest or lowest bidder, unless the contrary appears. (n) Art. 1327. The following cannot give consent to a contract: (1) Unemancipated minors; (2) Insane or demented persons, and deaf-mutes who do not know how to write. (1263a) Art. 1328. Contracts entered into during a lucid interval are valid. Contracts agreed to in a state of drunkenness or during a hypnotic spell are voidable. (n) Art. 1329. The incapacity declared in Article 1327 is subject to the modifications determined by law, and is understood to be without prejudice to special disqualifications established in the laws. (1264) Art. 1330. A contract where consent is given through mistake, violence, intimidation, undue influence, or fraud is voidable. (1265a) 1328 - Note 1327 - Notes PERSONS INCAPACITATED TO GIVE CONSENT 1. Minors 2. Insane persons 3. Demented persons; and 4. Deaf-mutes who do not know how to write LUCID INTERVAL A brief period during which an insane persons regains sanity sufficient to have the legal capacity to contract and act on his or her own behalf. 1329-1330 - Notes Article 1390 provides that a contract where one of the parties are incapable of giving consent is voidable or annullable. Article 1403(3) of the Civil Code provides that a contract where both parties are incapable of giving consent is unenforceable. VICES OF CONSENT 1. Mistake 2. Violence 3. Intimidation 4. Undue influence; and 5. fraud CHARACTERISTIC OF CONSENT 1. It should be INTELLIGENT 2. It should be FREE 3. It should be SPONTANEOUS Intelligence in consent is vitiated by error. Freedom is vitiated by violence, intimidation or undue influence Spontaneity is vitiated by fraud. Art. 1331. In order that mistake may invalidate consent, it should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract, or to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract. Mistake as to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties will vitiate consent only when such identity or qualifications have been the principal cause of the contract. A simple mistake of account shall give rise to its correction. (1266a) Art. 1332. When one of the parties is unable to read, or if the contract is in a language not understood by him, and mistake or fraud is alleged, the person enforcing the contract must show that the terms thereof have been fully explained to the former. (n) 1331 - Notes MISTAKE has been defined as a “misunderstanding of the meaning or implication of something “or” a wrong action or statement proceeding from faulty judgment xxx.” EXAMPLE: Mistake as to the object of the contract is the substitution of a specific thing contemplated by the parties with another. MISTAKE MUST BE SUBSTANTIAL 1. Mistake should refer to the substance of the thing which is the object of the contract; 2. Mistake should refer to those conditions which have principally moved one or both parties to enter into the contract; and 3. Mistake as to the identity or qualifications of one of the parties will vitiate consent only when such identity or qualifications have been the principal cause of the contract. Art. 1333. There is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract. (n) Art. 1334. Mutual error as to the legal effect of an agreement when the real purpose of the parties is frustrated, may vitiate consent. (n) 1334 - Notes RULE Mistake of law, does not render the contract voidable because of the well-known principle that ignorance of the law does not excuse anyone from compliance therewith. However, the above-stated rule is an EXCEPTION. REQUISITES: 1. The mistake must be with respect to the legal effect of an agreement 2. The mistake must be mutual; and 3. The real purpose of the parties must be frustrated. 1333 - Notes Article 1333 of the Civil Code, however, states that “there is no mistake if the party alleging it knew the doubt, contingency or risk affecting the object of the contract.” Under this provision of law, it is presumed that the parties to a contract know and understand the import of their agreement. To invalidate consent, the error must be excusable. It must be real error, and not that could have been avoided by the party alleging it. Art. 1335. There is violence when in order to wrest consent, serious or irresistible force is employed. There is intimidation when one of the contracting parties is compelled by a reasonable and well-grounded fear of an imminent and grave evil upon his person or property, or upon the person or property of his spouse, descendants or ascendants, to give his consent. To determine the degree of intimidation, the age, sex and condition of the person shall be borne in mind. A threat to enforce one's claim through competent authority, if the claim is just or legal, does not vitiate consent. (1267a) 1335 - Notes VIOLENCE There is violence when in order to wrest consent, serious or irresistible force is employed. REQUISITES OF VIOLENCE 1. The force employed to wrest consent must be serious or irresistible; and 2. It must be the determining cause for the party upon whom it is employed in entering into the contract. 1335 – Notes INTIMIDATION There is intimidation when one of the contracting parties is compelled by a reasonable and well-grounded fear of an imminent and grave evil upon his person or property, or upon the person or property of his spouse, descendants or ascendants, to give his consent. REQUISITES 1. Must be the determining cause of the contract, or must have caused the consent to be given. 2. That the threatened act be unjust or unlawful. 3. That the threat be real and serious, there being an evident disproportion between the evil and the resistance which all men can offer, leading to the choice of the contract as the lesser evil; and 4. That it produces a reasonable and well-grounded fear from the fact that the person from whom it comes has the necessary means or ability to inflict the threatened injury. Art. 1336. Violence or intimidation shall annul the obligation, although it may have been employed by a third person who did not take part in the contract. (1268) Art. 1337. There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. The following circumstances shall be considered: the confidential, family, spiritual and other relations between the parties, or the fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weakness, or was ignorant or in financial distress. (n) 1337 - Notes UNDUE INFLUENCE There is undue influence when a person takes improper advantage of his power over the will of another, depriving the latter of a reasonable freedom of choice. CIRCUMSTANCES TO BE CONSIDERED 1. The confidential, family, spiritual and other relations between the parties, or 2. The fact that the person, alleged to have been unduly influenced was suffering from mental weakness, or 3. The fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was ignorant, or 4. The fact that the person alleged to have been unduly influenced was in financial distress. 1338 - Notes To constitute fraud under Article 1338, the words and machinations must have been so insidious or deceptive that the party induced to enter into the contract would not have agreed to be bound by its terms if that party had an opportunity to be aware of the truth. FRAUD There is fraud when through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed upon. DOLO CAUSANTE OR CAUSAL FRAUD DOLO INCIDENTE OR INCIDENTAL Causal fraud to in Article 1338, are those deceptions or misrepresentations of a serious character employed by one party and without which the other party would not have entered into the contract. Dolo incidente or incidental fraud which is referred to in Article 1344, are those which are not without which the other party would still have entered into the contract Dolo causante determines or is the essential cause of the consent Dolo incidente refers only to some particular or accident of the obligations Effects of dolo causante are the nullity of the contract and the indemnification of damages Dolo incidente also obliges the person employing it to pay damages 1338 - Notes EXAMPLE OF CAUSAL FRAUD 1. When the seller, who had no intention to part with her property, was ‘tricked into believing’ that what she signed were papers pertinent to her application for the reconstitution of her burned certificate of title, not a deed of sale 2. When the signature of the authorized corporate officer was forges; or 3. When the seller was seriously ill, and died a week after signing the deed of sale raising doubts on whether the seller could have read, or fully understood, the contents of the documents he signed or of the consequences of his act. 1338 - Notes REQUISITES OF CAUSAL FRAUD 1. It must have been employed by one contracting party upon the other 2. It must have induced the other party to enter into the contract 3. It must have been serious 4. It must have resulted in damage and injury to the party seeking annulment Art. 1338. There is fraud when, through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed to. (1269) Art. 1339. Failure to disclose facts, when there is a duty to reveal them, as when the parties are bound by confidential relations, constitutes fraud. (n) Art. 1340. The usual exaggerations in trade, when the other party had an opportunity to know the facts, are not in themselves fraudulent. (n) Art. 1341. A mere expression of an opinion does not signify fraud, unless made by an expert and the other party has relied on the former's special knowledge. (n) Art. 1342. Misrepresentation by a third person does not vitiate consent, unless such misrepresentation has created substantial mistake and the same is mutual. (n) Art. 1343. Misrepresentation made in good faith is not fraudulent but may constitute error. (n) Art. 1344. In order that fraud may make a contract voidable, it should be serious and should not have been employed by both contracting parties. Incidental fraud only obliges the person employing it to pay damages. (1270) 1344 - Notes FRAUD Refers to all kinds of deception – whether through insidious machination, manipulation, concealment or misrepresentations that would lead an ordinarily prudent person into error after taking the circumstances into account. In contracts, a fraud known as dolo causante or causal fraud is basically a deception used by one party prior to or simultaneous with the contract, in order to secure the consent of the other. Needless to say, the deceit employed must be serious. In contradistinction, only some particular or accident of the obligation is referred to by incidental fraud or dolo incidente, or that which is not serious in character and without which the other party would have entered into the contract anyway. STANDARD PROOF FOR FRAUD Article 1344 CLEAR and CONVINCING EVIDENCE It is less then proof beyond reasonable doubt (for criminal cases) but greater than preponderance of evidence (for civil cases). The degree of believability is higher than that of an ordinary civil case. FRAUD BAD FAITH Must be established by clear and convincing evidence, preponderance of evidence is inadequate Imports a dishonest purpose or some moral obliquity and conscious doing of a wrong, not simply bad judgment or negligence. Art. 1345. Simulation of a contract may be absolute or relative. The former takes place when the parties do not intend to be bound at all; the latter, when the parties conceal their true agreement. (n) Art. 1346. An absolutely simulated or fictitious contract is void. A relative simulation, when it does not prejudice a third person and is not intended for any purpose contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy binds the parties to their real agreement. (n) ABSOLUTE SIMULATION There is a colorable contract but it has no substance as the parties has no intention to be bound by it. The apparent contract is not really desired or intended to produce legal effect. It is VOID. RELATIVE SIMULATION If the parties state a false cause in the contract to conceal their real agreement, the parties are still bound by the real agreement. SECTION 2. - Object of Contracts Art. 1347. All things which are not outside the commerce of men, including future things, may be the object of a contract. All rights which are not intransmissible may also be the object of contracts. No contract may be entered into upon future inheritance except in cases expressly authorized by law. All services which are not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy may likewise be the object of a contract. (1271a) Art. 1348. Impossible things or services cannot be the object of contracts. (1272) Art. 1349. The object of every contract must be determinate as to its kind. The fact that the quantity is not determinate shall not be an obstacle to the existence of the contract, provided it is possible to determine the same, without the need of a new contract between the parties. (1273) No contract may be entered into upon future inheritance except in cases expressly authorized by law REQUISITES 1. The succession has not been opened 2. The object of the contract forms part of the inheritance; and 3. The promissor has, with respect to the object, an expectancy of a right which is purely hereditary in nature Things Rights Services All things which are not All rights which are not All services which are not outside the commerce of men transmissible may also be the contrary to law, morals, good including future things, may be object of a contracts. customs, public order or public the object of a contract. policy may likewise be the object of contract. SECTION 3. - Cause of Contracts Art. 1350. In onerous contracts the cause is understood to be, for each contracting party, the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other; in remuneratory ones, the service or benefit which is remunerated; and in contracts of pure beneficence, the mere liberality of the benefactor. (1274) Art. 1351. The particular motives of the parties in entering into a contract are different from the cause thereof. (n) Art. 1352. Contracts without cause, or with unlawful cause, produce no effect whatever. The cause is unlawful if it is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. (1275a) WHAT IS CAUSE? In general, the cause is the WHY of the contract or the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into the contract. For the cause to be valid, it must be lawful such that it is not contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. Cause is the essential reason which moves the contracting parties to enter into it. In other words, the cause is the immediate, direct and proximate reason which justifies the creation of an obligation through the will of the contracting parties. Cause and Consideration In onerous contracts the cause is understood to be, for each contracting party, the prestation or promise of a thing or service by the other. In remuneratory contracts, the cause is the service or benefit which is remunerated. Cause in gratuitous contracts, the mere liberality of the benefactor. In our jurisdiction, cause and consideration are used interchangeably. Art. 1353. The statement of a false cause in contracts shall render them void, if it should not be proved that they were founded upon another cause which is true and lawful. (1276) Art. 1354. Although the cause is not stated in the contract, it is presumed that it exists and is lawful, unless the debtor proves the contrary. (1277) Art. 1355. Except in cases specified by law, lesion or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract, unless there has been fraud, mistake or undue influence. (n) 1355 – Notes GENERAL RULE Lesion or inadequacy or inadequacy of cause shall not invalidate a contract. EXCEPTIONS: 1. In cases specified by law 2. When there has been fraud 3. When there has been mistake; and 4. When there has been undue influence CHAPTER 3 FORM OF CONTRACTS Art. 1356. Contracts shall be obligatory, in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the essential requisites for their validity are present. However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. In such cases, the right of the parties stated in the following article cannot be exercised. (1278a) Art. 1357. If the law requires a document or other special form, as in the acts and contracts enumerated in the following article, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract. (1279a) A certain form may be prescribed by law for any of the following purposes: Validity of Contract Enforceability of Contract When the form required is for validity, its non-observance renders the contract VOID and of no effect. When the required form is for enforceability, non-compliance therewith will not permit, upon the objection of a party, the contract, although otherwise valid to be proved or enforce by action. Greater Efficacy or Convenience Formalities intended for greater efficacy or convenience or to bind third persons, if not done, would not adversely effect the validity or enforceability of the contract between the contracting parties themselves. 1356 Note However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable. To be Valid and Enforceable (Solemn Contracts) Law requires to be PROVED by some WRITING of its terms 1. Donation of an immovable property 1. Covered by Statute of Frauds under that the law requires to be embodied in Article 1403(2) off the Civil Code. a public instrument in order that the donation may be valid, existing or 2. Their existence not being provable by binding. (Art. 1318) mere oral testimony (unless wholly or 2. Donations of movables worth more partly executed), these contracts are than P5,000 which must be in writing, exceptional in requiring a writing otherwise the donation is void. (Art. embodying the terms thereof for their 748) enforceability by action in court. 3. Contracts to pay interest on loans (mutuum) that must be expressly stipulated in writing (Art.1956) Art. 1358. The following must appear in a public document: (1) Acts and contracts which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable property; sales of real property or of an interest therein a governed by Articles 1403, No. 2, and 1405; (2) The cession, repudiation or renunciation of hereditary rights or of those of the conjugal partnership of gains; (3) The power to administer property, or any other power which has for its object an act appearing or which should appear in a public document, or should prejudice a third person; (4) The cession of actions or rights proceeding from an act appearing in a public document. All other contracts where the amount involved exceeds five hundred pesos must appear in writing, even a private one. But sales of goods, chattels or things in action are governed by Articles, 1403, No. 2 and 1405. (1280a) Art. 1403. The following contracts are unenforceable, unless they are ratified: (2) Those that do not comply with the Statute of Frauds as set forth in this number. In the following cases an agreement hereafter made shall be unenforceable by action, unless the same, or some note or memorandum, thereof, be in writing, and subscribed by the party charged, or by his agent; evidence, therefore, of the agreement cannot be received without the writing, or a secondary evidence of its contents: (a) An agreement that by its terms is not to be performed within a year from the making thereof; (b) A special promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another; (c) An agreement made in consideration of marriage, other than a mutual promise to marry; (d) An agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money; but when a sale is made by auction and entry is made by the auctioneer in his sales book, at the time of the sale, of the amount and kind of property sold, terms of sale, price, names of the purchasers and person on whose account the sale is made, it is a sufficient memorandum; (e) An agreement of the leasing for a longer period than one year, or for the sale of real property or of an interest therein; (f) A representation as to the credit of a third person. Reference: Obligation and Contracts by Atty. Andrix Domingo, CPA And New Civil Code