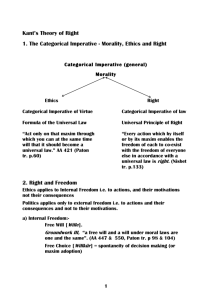

Kant’s Categorical Imperative Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy.co.uk © Michael Lacewing Deontology • Morality is a matter of duty. • Whether something is right or wrong doesn’t depend on its consequences. Actions are right or wrong in themselves. • We each have duties regarding our own actions. Kant’s Categorical Imperative • Morality is meant to guide our actions. • We act on maxims: principle of action, what we intend. • Morality is universal, the same for everyone. • so “Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”. The two tests • ‘contradiction in conception’: a maxim is wrong if the situation in which everyone acted on that maxim is somehow selfcontradictory. • E.g. stealing: If we could all just help ourselves to whatever we wanted, the idea of ‘owning’ things would disappear; but then no one would be able to steal. The two tests • contradiction in will: It is logically possible to universalize the maxim, e.g. ‘not to help others in need’ (even though it would be unpleasant). But we can’t will this, because we might need help, and to will an end is to will the means. Imperatives • An imperative is just a command. • A hypothetical imperative is a command that presupposes some further goal or end. • A categorical imperative is not hypothetical. It is irrational and immoral not to obey it. Happiness and reason • Only reason and happiness motivate us. Morality motivates us, so must be one of these. • It can’t be happiness, since what makes people happy differs, and happiness can be good or bad. • It is reason: morality is universal and categorical - so is reason. Objections • Any action can be justified, as long as we phrase the maxim cleverly. – But the test is what our maxim really is. • Conflict of duties – Duties never really conflict, but knowing how to apply the CI requires judgment. • Strange results: ‘I shall never sell, but only buy’ is immoral! Respecting humanity • ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’ • To treat someone’s humanity simply as a means, and not also as an end, is to treat the person in a way that undermines their power of making a rational choice themselves.