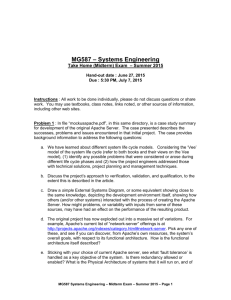

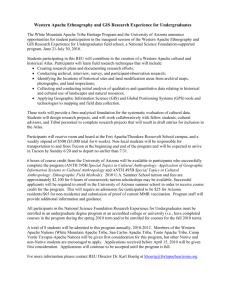

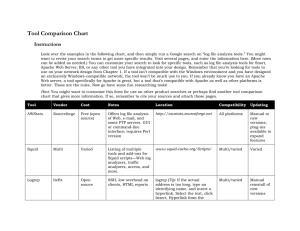

For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 9-201-113 REV: AUGUST 27, 2001 LISA MEULBROEK Risk Management at Apache Introduction By March of 2001, managers at Apache Corporation, an independent oil and gas exploration and production company, had reason to be optimistic. While oil prices had softened somewhat recently, at $27 a barrel they were much higher than the pernicious levels of 1998, when oil bottomed out at $11 per barrel. Apache had just closed on the acquisition of Repsol in Egypt's Western desert and, along with its partner Shell Overseas Holdings, had also acquired Fletcher Challenge Energy, for a combined cost of $1 billion. The value of such acquisitions, however, depended in large part on the future prices of oil and gas. To decrease its exposure to oil and gas price volatility, Apache had begun a limited hedging program centered mostly on its recently acquired properties. Apache’s managers knew that hedging could create its own risks, and so it seemed prudent to re-evaluate the success of the new program. The decision facing Apache’s managers was whether the firm should continue hedging, and if so, should its current program be extended beyond hedging the revenues from acquisitions? Apache Corporation Apache Corporation was founded in 1954 by Raymond Plank, its current Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. Mr. Plank’s son, Roger, was the company’s current CFO, but the company was not controlled by the Plank family, and in fact, officers and directors as a group held less than 1.25% of the company’s common stock (see Exhibit 1-3 for Apache’s Income Statement, Balance Sheet, and Cash Flow Statement). By 2001, Apache had evolved into a large independent oil company that explored, developed, and produced oil and natural gas in North America, with offshore exploration and production interests in Egypt and Australia the most important of its international regions. It also had exploration interests in Poland, and offshore China. Under Mr. Plank’s leadership, production had grown for 23 consecutive years, including about 28% in 2000, and a predicted 25% or more for 2001. In 2000, some 45% of total production was North American natural gas, and Apache’s reserves were fairly evenly split between oil and gas. Exhibit 4 shows Apache’s oil and gas revenues and costs by country. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Professor Lisa Meulbroek prepared this case with the assistance of Research Associate Puja Malhotra. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management. Copyright © 2001 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Harvard Business School. This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache Apache's strategy was to maximize production and to minimize cost. Specifically, management sought to increase oil and gas reserves, production, cash flow and earnings through a combination of exploratory drilling, development of existing projects, and select property acquisitions. To retain control over development, Apache preferred to operate its own properties, and was currently operating the properties responsible for over eighty percent of its production. While its North American operations focused on development of more mature properties (eighty percent of the company’s proved reserves were located in North America), Apache’s international operations were more exploration-oriented. Its strategy was to concentrate its efforts, hoping to become the dominant operator in a region. Apache viewed its international operations as riskier than its domestic operations: not only were the properties themselves less mature than the North American holdings, but political risk compounded the greater geological uncertainty. Apache avoided international areas with the most risk, such as West Africa, or territory within the former Soviet Union. Exhibit 5 shows the results of Apache’s drilling programs in the U.S. and internationally. In addition to exploiting Apache’s existing asset base through a combination of workovers, re-completions, and moderate risk drilling, Apache’s managers sought out acquisitions where they could add value. This entailed enhancing the reserves, consolidating properties, and accelerating a property’s cash flows, which could then be used to pay down the debt incurred in purchasing the property. Apache’s compensation program reflected its goals of maximizing production while minimizing costs. Incentive bonuses were frequently based upon growing both reserves and production and keeping costs low. In 2000, this meant that executives were eligible for a bonus above the target of fifty percent of their base salaries if the company acquired or brought under its management assets valued in excess of $1 billion while maintaining an acceptable debt-to-capitalization ratio of 45 percent or less. Apache’s long-term incentive compensation plan called for all employees to receive additional compensation if the company achieved target stock price levels of $100, $120, and $180 by year-end 2004. Moreover, if production per share doubled to projected levels, additional compensation would be granted. This goal was derived from a recognition that oil and gas price levels were outside the control of managers, but production levels were not, and so sought to reward managers for the variables within their control. High oil and gas prices had made the past year extraordinary in many respects. While able to defer anywhere from 70-80% of its taxes, it was still the first year in some time that Apache had to pay any taxes. The company had also made an unusual number of acquisitions in 2000. These acquisitions included producing properties in Oklahoma and Texas from Repsol for $149 million, producing properties in the Permian Basin and S. Texas for $321 million from Collins & Ware, properties in the Gulf of Mexico from Occidental Petroleum for $321 million (plus an additional $44 spread out over the next four years), Canadian properties from Phillips Petroleum for $490 million, and miscellaneous tactical regional acquisitions for $104 million. Together, the reserves added through such acquisitions replaced the amount that Apache had actually produced during 2000 four times over. As Apache moved into 2001, they had acquired over $1 billion in property by March. Apache’s managers also anticipated spending an additional $1 billion in capital expenditures in 2001, mostly for exploration activity. Financial flexibility was considered a critical element in the execution of these plans, and the rating agencies had recently upgraded Apache’s rating to “A-” from “BBB+” in recognition of their success along these lines. And, over the past two years, Apache had financed $3.7 billion worth of acquisitions, while maintaining a debt ratio of about 40%, and interest coverage ratio of six times. Exhibit 6 details Apache’s acquisitions and financing. 2 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache 201-113 The Oil and Gas Industry Apache represented one of several types of independent oil companies. Very small secondary players, the “mom and pop” companies of the oil industry, were low-tech and low-cost. Wildcatters, another category of independent oil companies, drilled speculatively for oil, with only a limited amount of testing involved before drilling. Apache represented a final type of independent, one larger than the small secondaries, who managed virgin fields in addition to the more mature properties. This category included not only Apache, but also firms such as Ocean Energy (formerly called Seagull) and Burlington Resources. Apache was not only larger than many independent oil companies, it also had a reputation for being technically advanced. Exhibit 7 shows Apache’s stock price performance relative to major and secondary oil companies. Exhibit 8 compares key firm characteristics. As a field matured, oil production declined exponentially. Roughly one-third to one-half of oil in a particular field was recovered via “conventional means,” at which point secondary recovery techniques, which were more costly, were required. Secondary recovery techniques involved pumping various substances into the ground to encourage oil to come closer to the surface. For example, water might be used to keep up the oil pressure, enabling it to be pumped. Underground fields were even set on fire to heat viscous oil in order to increase the oil’s fluidity and facilitate pumping. So, as production continued for a given field, the costs of bringing the oil to the surface increased. The continual depletion of reserves also meant that oil companies had a persistent need to replenish those reserves. Oil exploration and production in the U.S. and Canada had gone on longer than in most areas of the world, making the oil fields in the U.S. and Canada the most mature fields in the world. As a field matured, the major oil companies typically sold it to a secondary, or independent, oil company. The smaller firms who acquired the mature fields generally had lower cost structures which allowed them to efficiently exploit fields that the majors, with their higher cost structures could not. In part, the lower cost structures possessed by the independent firms resulted from their leaner staffs: unlike the major oil companies, the smaller independent firms tended not to have specialists for every type of analysis. In purchasing a field from a major oil company, the independent also purchased the “work” done on that field. Typically, by the time one of the independent firms purchased a field, the major oil companies had already incurred some of the large costs, such as 3-D seismic surveys, and, of course, the purchase price therefore reflected such work done on a field. While many of the oil properties in the United States were mature, leading the major oil companies to reduce their exploration and development in the United States, the same was not true of natural gas. The United States still had a large supply of on-shore gas, and exploration and production of natural gas continued. The stock of gas was greater than the stock of oil, and had the advantage of being a very clean technology. Water and CO2 were the primary by-products of burning gas, which were easier to dispose of than the nitrogen and sulfur compounds that result from burning oil. The United States also had an extensive pipeline system that allowed for transport of gas throughout the country. Outside the United States, though, such extensive coverage was rare, and the ability of producers to transport gas from its source without a pipeline was limited. Efforts were underway to ease transportation limitations by efficiently changing the state of gas to a liquid so that it could be transported by ship, but such technology was not yet available. Oil was clearly easier to transport, and had the additional advantages that more markets for it existed, and it was useful in ways that gas was not (e.g. the production of plastic or fertilizer). Hydrocarbon accumulations, however, were typically a mixture of oil and gas, because oil and gas were co-miscible (they dissolve in each other). The amount that could dissolve was a function of 3 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache pressure and temperature (i.e. depth), and the ratio of oil-gas in the ground was not the same as that at the wellhead. Gas was always present in oil, and usually some liquids were dissolved in gas, although the amounts could vary tremendously. The presence of any liquids was usually very good for the viability of a project, as it meant a higher energy density. Some flexibility surrounded the speed of producing oil, but physical limits tempered that flexibility. An oil or gas reservoir could be damaged if production is too fast or too slow. The appropriate speed was determined largely by the reservoir type (sandstone, carbonate, etc.), what combinations of water, oil, and gas were present, and the "drive mechanism" (water drive, depletion drive, etc.). If the reservoir was in secondary or tertiary recovery (i.e. fluid is used to force oil out of the reservoir), flexibility in production rates would be very limited. Injection and production rates were critical parameters for optimal secondary or tertiary recovery. The rate of gas production had its limits, too, although in general, the rate of gas production was more flexible than that of oil production. In addition to physical constraints on pumping speeds, competitive concerns also affected the speed of production. The threat of a competitor with wells in an adjacent lease gave a firm a strong incentive to maintain production, in order to prevent that competitor from draining the firm’s own reserves. High fixed costs, state regulated maximum production limits, and contractual issues with partners and royalty owners all had the potential to limit a company’s ability to vary production. Apache’s general approach to production speed was to run “flat out,” pumping as quickly as possible. Consequences of Price Volatility Oil and gas price changes (see Exhibit 9 for historical volatility levels) affected the production and development of properties. When the price of oil was low, production tended to shift away from the United States, due to its relatively high cost of producing oil. In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, moving oil from the seafloor to the platform cost approximately $12 per barrel. In Saudi Arabia, however, costs were much lower, on the order of $0.15 to $0.50 per barrel. During the last period of low oil prices in 1999, many of the major oil companies considered withdrawing from the United States altogether. Indeed, the primary remaining oil interest the majors had in the United States was in deep-water drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. Deep-water drilling had large fixed costs, with production platforms costing roughly one billion dollars to establish, and the risks were considerably higher. In a graphic illustration of the risks involved in offshore production, the world’s largest oil platform had recently tipped over sideways and submerged into the ocean off of Brazil. Oil prices also affected the costs and the availability of drilling rigs. When prices were high, rigs were booked up to 18 months in advance, whereas when prices were low, the oil companies cut their capital expenditures, leaving many rigs tied up at docks, rusting. As oil prices dropped, firms had to decide whether to “shut in” a well. Closing a well was to a certain extent a one-way option. Closing could damage the reservoir; starting up production again could be difficult. Shutting in eliminated the fixed cost of maintaining the well’s structure at the expense of requiring large start-up costs to re-drill the well again. Drilling on-shore cost perhaps one or two million dollars per well, with each field comprising in the range of twenty to fifty wells. Reservoir engineers and geologists could also be laid off to reduce fixed costs, and platform workers could also be dismissed, keeping only a skeleton crew remaining to run the rig. Of course, firing such personnel often meant loosing a great deal of institutional knowledge about a particular reservoir. Nonetheless, the petroleum business was notorious for large layoffs in times of low oil prices, followed by the addition of many employees when oil prices are high. Moreover, oil and gas producers had a reputation for mis-using the increased cash flows that resulted from higher oil 4 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache 201-113 prices, spending too much money drilling wells, or paying too much for properties when oil prices were high. There was a sense among Apache’s managers that the hiring and firing cycles were extremely costly to the firms, a view supported by some outside observers. Speaking to the importance of what he termed “specific knowledge,” that is, the knowledge of local geological and business conditions, Jeff Sandefer from Sandefer Capital, a fund investing in energy companies, noted that: The people that tend to win in this business are the old timers that have played in one region—say, the same county in North Central Texas—for 20 or 30 years. The large companies tend to move people around and, as a result, they fail to develop specific knowledge. When you move from one geographic basin to another—from, say, a tertiary recovery CO2 flood in West Texas to the deep drilled wells in the Rocky Mountains—you enter a new world; everything changes. But the guys who have been in the same place for 30 years have seen all the ups and downs. They know how the service companies cycle in and out. They understand the operating leverage inherent in the assets. They understand that this little squiggle on the log here means one thing here, and, if you move over four miles, the same little squiggle means something else.1 Oil price volatility also had the potential to disrupt acquisitions and development of current assets. The low prices of oil in 1999, for example, disrupted Anadarko Petroleum’s (another independent oil producer) five-year development and production plan. This plan had called for spending more than its expected cash flow, and funding the shortfall with debt. As oil and gas prices dropped, and the company’s cash flows dropped below forecasted levels, Anadarko’s managers felt the company’s leverage had become too high, and were forced to sell $100 million in assets, and issue $240 million in equity to put the company back on track.2 Exhibits 10 and 11 show the relation between oil and gas producers stock returns and oil and gas price changes. Risk Management in the Oil Industry Oil futures had been traded as early as the 1800s, only to all but disappear until the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) introduced a futures contract on heating oil in 1978, eventually followed by a futures contract on crude oil in 1983.3 Much of the market in energy derivatives, did not occur on an exchange at all, taking place instead in the “over-the-counter” market, where the counterparts to the trade arranged the trade privately without an exchange to intermediate. One advantage of the rapidly developing markets in energy derivatives was that they substantially lowered trading costs. While a producer who signed a long-term fixed-price contract with a consumer for a physical commodity was functionally accomplishing the same kind of risk transfer, the search costs of finding an appropriate counterpart in these “one-off” contracts were high. Of 1 “Energy Derivatives and the Transformation of the U.S. Corporate Energy Sector,” in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 13, Number 4, Winter 2001, pp. 50-75. 2 “The Rising Tide Hasn’t Lifted All Boats – Yet,” in Energy Conference Review, Merrill Lynch Report, November 9, 1999. Note that even when oil prices picked up, Anadarko continued to spend more than its cash flows, as their goal was to more than replace their reserves. Anadarko’s increases in reserves had more than fully replaced its annual production for the past 18 years. 3 Much of the background information in this section is drawn from “Energy Derivatives and the Transformation of the U.S. Corporate Energy Sector,” in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 13, Number 4, Winter 2001, pp. 50-75. 5 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache course, standardized contracts had disadvantages too: they exposed participants to “basis risk.” Standardized contracts were priced for delivery at a specific point; in the case of gas, this meant the Henry Hub in Louisiana. The company entering the contract was responsible for getting the gas to the Henry Hub, meaning that this portion of the cost would be unhedged even after entering into hedging contracts. Apache’s exposure to this basis risk had proved costly in the past when it found itself unable to ship gas to the Henry Hub to settle contracts, but basis risk, at least in theory, could be minimized through over-the-counter contracts with dealers such as Goldman Sachs. Embracing these new financial instruments were some firms, like Enron, who had completely transformed their business operations through the use of derivatives. Gene Humphrey, Chairman and CEO of Enron’s Investment Partners subsidiary, explained that Enron used “…financial techniques such as hedging with derivatives to reduce our need for financial capital, while making the most of our intellectual capital....” Echoing this endorsement, John McCormack of Stern Stewart’s energy and real options practice noted that: Companies that hedge major price risks, all other things equal, reduce the amount of equity they need to support their operations. And, to the extent that it increases the amount of leverage a company can support with a high degree of confidence, corporate hedging can reduce the company’s overall cost of capital. Moreover, for companies that need to raise outside capital, I would argue that hedging has the potential to increase their access to capital markets, and to improve the terms on which they raise that capital.4 Humphrey of Enron argued for the importance of managing risk for independent exploration and production companies. He noted that in the late ‘80’s and early ‘90’s low prices created a “credit crunch,” making it difficult for the firms to get access to capital. Enron offered these firms “volumetric production payments” (VPP’s), where the firm received funding upfront for future production, and in return promised to deliver a fixed volume of product in the future. Humphrey was convinced that “…there were several companies we did this with that I think would otherwise have gone under because they didn’t have any other sources of capital.”5 Ron Erd, Vice President of Southern Company Energy Marketing, another supplier of structured derivative products, offered that “…with the help of derivatives… industrial companies can choose to focus on managing just those risks where they have a comparative advantage. But, in those cases where other players have a clear comparative advantage, the company can transfer those risks to those other players, whether they be other industrials, or financial players.”6 Supporters of hedging also pointed to the ability of hedging to facilitate better performance evaluation, allowing investors to evaluate the firm’s overall performance, and also permitting the firm to evaluate the performance of specific divisions or projects. As explained by Sheridan Titman, Director of the University of Texas’s Center for Energy Finance Research and Education, and Professor of Finance: 4 “Energy Derivatives and the Transformation of the U.S. Corporate Energy Sector,” in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 13, Number 4, Winter 2001, pp. 50-75. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 6 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache 201-113 For companies that are able to manage major price risks it’s much easier to evaluate people based upon output rather than on input…because a lot of the components of output that basically add noise to our measures of managerial performance can be hedged away. For example, if someone is responsible for managing the New Mexican oil region, his performance no longer has to be subject to oil price risk. With that source of volatility eliminated, what remains is a much more reliable performance measure—one that does a better job of reflecting the manager’s performance with respect to those factors over which he exercises a large degree of control.7 Some proponents of hedging believed that the increased ability to evaluate performance was especially useful in the oil industry, where the historic emphasis tended to first center on how much oil had been produced, and then on how much of a firm’s reserves had been replaced, rather than on the value created (or not) through those actions. Finally, some companies viewed risk management as an essential element of their business strategy. Statoil, Norway’s state-owned oil company, was reported to have one of the world’s most sophisticated and effective enterprise-wide risk management practices outside those found in financial firms. Petter Kapstad, Statoil’s controller, explained that the firm viewed risk management as essential to their business operations: “Our risk management system is really just the result of an investigation into our business and the best way to manage it. We didn’t suddenly say one day: ‘We want an enterprise-wide risk management system.’ We just decided that we wanted to look closely at our business. It can never be a negative to have a better understanding of the business you run.”8 Despite these encomiums, skepticism about the usefulness and desirability of transferring risk away from the oil companies remained. After all, risk reduction was costly; it consumed management time and resources. Moreover, companies that sold production forward would be forgoing the upside if prices were to increase, and firms that used options to “retain the upside” would pay a premium up front to get rid of the downside risk. In the end, it was far from clear that transferring risk created value, and, for the most part, the major integrated oil companies had shown little interest in using derivatives to manage their price exposures. Some analysts supported this practice, noting that investors buy shares in such companies for the exposure to oil risk, making hedging counter-productive. Tom Dougherty, general manager of risk management at Texaco, explained that Texaco’s share price had increased more than twenty percent last summer as oil prices increased. If Texaco had hedged its oil price exposure, that increase in shareholder value would have never occurred.9 Finally, hedging could be risky simply because it had not become “standard practice” in much of the industry. Thus, if prices increased, a company that hedged was likely to find itself relatively alone when its competitors were raking in profits, and if prices decreased, profits might be low, but at least unhedged companies had plenty of company (Exhibit 12 shows hedges-inplace for years 2000 and 2001 for many firms). While not yet widespread in the oil and gas business, hedging did occur in some other industries facing similar price fluctuations. In fact, the airlines had adopted hedging strategies that resembled some of Apache’ s option-based hedging practices. 7 Ibid., p. 68. 8 “Statoil steers a steady course,” Enterprise-Wide Risk Management Special Report in Risk Magazine, December 2000, p. S6. 9 “Who needs firm-wide risk?” Enterprise-Wide Risk Management Special Report in Risk Magazine, December 2000, p. S3. 7 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache Apache's Hedging Practices Apache had recently begun the practice of hedging the expected production from its new acquisitions. The price of natural gas on the futures market had been high relative to historical levels, and in fact the futures prices exceeded the market price for reserves in the ground. Conventional wisdom suggested that acquisitions during a time of high prices should be avoided as they generally seemed to result in “buying high, selling low,” a less-than-optimal strategy. In fact, many of Apache’s competitors had remained on the sidelines, avoiding acquisitions, because they believed prices would not stay at such high levels. Apache’s view was that the current environment offered the company the opportunity to negotiate the purchase of excellent properties, at potentially attractive prices. Through hedging, Apache’s managers locked in these high gas prices. For example, the prior August Apache had bought Occidental Petroleum’s reserves in several Gulf of Mexico fields for $365 million. This price amounted to roughly $1.12 per thousand cubic feet of reserves. Apache used “costless collars” (i.e. selling a call, buying a put with the proceeds from the call used to pay for the put) to lock in a price floor of $3.50, while preserving the upside up to $5.26 per thousand cubic feet. These hedges concentrated on the expected production over the next two to three years (markets were liquid to perhaps five years out, sometimes more).10 Regarding that acquisition, Apache’s controller, Thomas Mitchell, further explained that “any hedging strategy must be grounded in a market view; at Apache, our near-term view is generally bullish. We believe that oil prices reflect renewed discipline by the OPEC nations that have successfully reduced inventories in the world system during a period of strong demand… We also believe the North American natural gas market is in a period of supply shortfall, which is the result of the collapse in the industry’s gas well drilling activity during 1998 and early 1999.” Apache’s CFO, Roger Plank, reckoned that even after the cost of extraction, the acquisition in combination with its hedging strategy assured Apache a “double-digit” return. In Plank’s view, the collars provided good protection against a potential downturn, but they left upside potential consistent with Apache’s view of a tight market. Through hedging, Plank thought Apache was able to purchase high quality properties at low cash flow multiples. This strategy, however, was not itself without risk: Apache would forgo any additional profits that would accrue if prices were to increase too much. Indeed, by March of 2001, gas prices had continued to rise above Apache’s call price of $5.26.11 Yet, as Plank noted, Apache’s hedging program had yielded projected production levels in 2001 that exceeded the prior year’s production by at least 25%. Because U.S. production was shrinking, prices remained robust, leading to record financial results. Aside from the obvious financial benefits, Apache’s managers thought hedging had benefited the firm in a more subtle way: hedging contributed to the firm’s credibility in the acquisition process. The ability to carry through on a deal quickly, combined with its reputation of always closing on a deal, gave Apache a big advantage in the acquisitions market. By adding to the firm’s financial flexibility, hedging increased Apache’s ability to execute quickly. Apache was not alone in its practice of hedging the production of newly-acquired companies: Newfield Exploration had recently used the same approach in an acquisition. Apache’s efforts had brought both accolades and disapprobation. In announcing its upgrade of Apache’s debt to A-, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) had cited Apache’s hedging practices along with its overall conservative financial practices. S&P concluded that “even if prices were to revert to very depressed levels, the 10 As far as financing the acquisition itself, Apache subsequently issued equity to bring its debt to total capitalization ratio down to 39% (Apache had a long history of re-balancing its capital structure following acquisitions). 11 Apache’s hedging was limited to acquisitions. Explained Roger Plank, "Our approach is to leave our base unhedged, but to use hedges on acquisitions to build the company. Acquisition economics are hypersensitive in the first few years of investment, so we try to protect through a period of payout." 8 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache 201-113 company is likely to maintain adequate coverage of fixed charges and capital expenditures needed to replace production. Financial flexibility remains strong, given the company’s access to $1.5 billion of available bank credit lines, a flexible capital spending budget, salable assets, and its very extended debt maturity schedule.”12 CFO Magazine simply noted that “Apache has a reputation for solid financial management.”13 Even investors who had initially been opposed to any hedging seemed to support Apache’s hedging strategy. Yet, some oil and gas producers had made very deliberate decisions to avoid hedging. EOG Resources, a natural gas producer spun off of Enron, decided in 1999 that the industry was entering a sustained tight gas market, and therefore elected to be entirely unhedged towards natural gas prices going forward.14 And hedging was not the only risk management strategy available. Managers at Talisman Energy, the largest Canadian-based oil and gas producer, thought that the company’s size gave it liquidity and stability, and diversified its technology risk. Size also gave it the strength to undertake many projects at the same time.15 The latest down cycle in energy prices had convinced some companies of the value of maintaining a strong balance sheet. Union Pacific Resources, for example, recognized that without hedging, its large cash acquisitions created a dangerous degree of exposure, and began concentrated efforts to de-lever to restore financial flexibility.16 Other companies viewed technology and low costs as a way to manage risk exposure. Vastar Resources, for instance, had done well during 1999’s downturn by keeping its costs down. Vastar chose projects near existing infrastructures to reduce startup time and costs, and management believed that this practice was integral to their high exploration success rate. They also viewed better and more experienced interpretation of 3D-seismics as a way to lower drilling risk.17 The Decision Apache’s managers wanted to chart a well-defined risk management strategy. Before continuing any further with hedging, they wanted to establish whether transferring risk from Apache’s shareholders to some other company or investor at a market-determined price would create value for Apache’s shareholders. And if managing risk turned out to maximize shareholder value, they wondered how, if at all, operational methods to manage risk could be used to supplement or substitute for hedging, and whether their own views on the future price path of oil and gas should shape their strategy. Finally, they were concerned about how to adjust their use of derivatives in the face of a new accounting requirement, FAS 133. FAS 133, which had become effective on January 1, 2001, required companies to mark-to-market all their derivative positions, and to report gains and losses on their income statement, without reporting any offsetting changes in the value of the underlying asset that is being hedged. Ironically, the end result for many firms might be that hedging actually created, rather than dampened, apparent volatility in reported earnings. 12 Standard & Poor’s CreditWire, Jan. 26, 2001. 13 Tim Reason, CFO Magazine, April 2001, p. 36. 14 “The Rising Tide Hasn’t Lifted All Boats – Yet,” in Energy Conference Review, Merrill Lynch Report, November 9, 1999. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 9 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 1 Risk Management at Apache Apache Income Statement ($ thousands) 12/31/2000 12/31/1999 12/31/1998 12/31/1997a 12/31/1996a $2,290,759 $1,143,946 $761,188 $983,773 $833,164 196,951 142,868 REVENUES: Oil and gas production revenues Gathering, processing and marketing revenues Equity in income (loss) of affiliates Other revenues 862 (7,717) 153 (1,558) (1,683) (2,768) (281) 2,454 840 1,400 2,283,904 1,146,553 760,470 1,176,273 977,151 583,546 442,844 382,807 381,416 315,144 OPERATING EXPENSES: Depreciation, depletion and amortization: Recurring Additional -- Lease operating costs Severance and other taxes -- 243,178 255,251 190,576 182,138 59,173 32,400 28,642 -- -- Operating costs 231,370 225,527 Gathering, processing and marketing costs 194,279 138,768 Administrative, selling and other 75,615 53,894 40,731 38,243 35,911 168,121 132,986 119,703 105,148 89,829 Financing costs: Interest expense Amortization of deferred loan costs Capitalized interest Interest income 2,726 4,854 4,496 6,438 5,118 (62,000) (53,231) (49,279) (36,493) (30,712) (2,209) 1,080,223 INCOME (LOSS) BEFORE INCOME TAXES Provision (benefit) for income taxes INCOME (LOSS) BEFORE CHANGE IN ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLE Cumulative effect of change in accounting principle, net of income tax NET INCOME (LOSS) Preferred stock dividends INCOME (LOSS) ATTRIBUTABLE TO COMMON STOCK (2,343) (4,383) (2,768) (2,629) 801,980 948,033 917,633 776,956 1,203,681 344,573 (187,563) 258,640 200,195 483,086 143,718 (58,176) 103,744 78,768 720,595 200,855 (129,387) 154,896 121,427 (7,539) -- -(129,387) -154,896 -- 713,056 200,855 19,988 14,449 $693,068 $186,406 ($131,391) $154,896 $121,427 $5.94 $1.73 ($1.34) $1.71 $1.42 2,004 -- 121,427 -- BASIC NET INCOME (LOSS) PER COMMON SHARE: Before change in accounting principle Cumulative effect of change in accounting principle -0.07 -- -- -- $5.87 $1.73 ($1.34) $1.71 $1.42 Before change in accounting principle $5.73 $1.72 ($1.34) $1.65 $1.38 Cumulative effect of change in accounting principle (0.06) DILUTED NET INCOME (LOSS) PER COMMON SHARE: $5.67 -$1.72 -($1.34) -$1.65 $1.38 Source: Apache 2000 10-K for years 1998-2000 and Apache 1998 10-K for years 1996-1997. a In 2000, change in accounting principle to carry crude oil inventories at cost not market value in accordance with SEC announcements. 10 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache Exhibit 2 201-113 Apache Consolidated Balance Sheet ($ thousands) 12/31/00 12/31/99 ASSETS CURRENT ASSETS: Cash and cash equivalents Receivables 37,173 13,171 506,723 259,530 Inventories 54,764 45,113 Advances to oil and gas ventures and other 31,360 25,254 630,020 343,068 9,423,922 7,409,787 PROPERTY AND EQUIPMENT: (Oil and gas, on the basis of full cost accounting:) Proved properties Unproved properties and properties under development, not being amortized 977,491 869,108 Gas gathering, transmission and processing facilities 573,621 442,437 Other Less: Accumulated depreciation, depletion and amortization 119,590 105,635 11,094,624 8,826,967 (4,282,162) (3,711,109) 6,812,462 5,115,858 39,468 7,481,950 43,617 5,502,543 OTHER ASSETS: Deferred charges and other LIABILITIES AND SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY CURRENT LIABILITIES: Current maturities of long-term debt Accounts payable Accrued operating expense 25,000 6,158 259,120 148,309 23,893 18,226 143,916 101,490 Accrued compensation and benefits 34,695 22,631 Accrued interest 25,947 28,118 Other accrued expenses 40,776 11,846 553,347 336,778 2,193,258 1,879,650 Accrued exploration and development LONG-TERM DEBT DEFERRED CREDITS AND OTHER NONCURRENT LIABILITIES: Income taxes 699,833 360,324 Advances from gas purchasers 153,106 180,956 Other 127,766 75,408 980,705 616,688 98,387 98,387 208,207 210,490 COMMITMENTS AND CONTINGENCIES (Note 10) SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY: Preferred stock, no par value, 5,000,000 shares authorized--Series B, 5.68% Cumulative Preferred Stock,100,000 shares issued and outstanding Series C, 6.5% Conversion Preferred Stock, 138,482 and 140,000 shares issued and outstanding, respectively Common stock, $1.25 par, 215,000,000 shares authorized 126,500,776 and 116,403,013 shares issued,respectively 158,126 145,504 Paid-in capital 2,173,183 1,717,027 Retained earnings 1,226,531 558,721 Treasury stock, at cost, 2,866,028 and 2,406,549 shares, respectively (69,562) Accumulated other comprehensive loss (40,232) 3,754,640 7,481,950 (52,256) (8,446) 2,669,427 5,502,543 Source: Apache 2000 10-K 11 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 3 Risk Management at Apache Apache Statement of Consolidated Cash Flows ($ thousands) 12/31/00 12/31/99 12/31/98 713,056 200,855 (129,387) Depreciation, depletion and amortization 583,546 442,844 625,985 Provision (benefit) for deferred income taxes 350,703 77,494 (81,856) Amortization of deferred loan costs 2,726 4,854 4,496 Cumulative effect of change in accounting principle 7,539 Other 9,719 Other non-operating activities 8,251 CASH FLOWS FROM OPERATING ACTIVITIES: Net income (loss) Adjustments to reconcile net income (loss) to net cash provided by operating activities: -1,533 --- (387) 1,887 65,487 Changes in operating assets and liabilities, net of effects of acquisitions: (Increase) decrease in receivables (253,721) (103,167) (Increase) decrease in advances to oil and gas ventures and other (6,167) (15,330) 3,879 (Increase) decrease in deferred charges and other (1,562) (2,356) 13,238 111,841 24,912 (65,851) 45,281 26,233 (12,161) Increase (decrease) in advances from gas purchasers (27,850) (24,512) 50,922 Increase (decrease) in deferred credits and noncurrent liabilities (13,976) 5,201 Increase (decrease) in payables Increase (decrease) in accrued expenses NET CASH PROVIDED BY OPERATING ACTIVITIES (5,128) 1,529,386 638,174 471,511 (1,010,528) (591,316) (699,509) (19,884) 38,774 CASH FLOWS FROM INVESTING ACTIVITIES: Additions to property and equipment Non-cash portion of net oil and gas property additions 42,934 Acquisition of Phillips properties (490,250) -- -- Acquisition of Occidental properties (321,206) -- -- Acquisition of Collins & Ware properties (320,682) -- -- Acquisition of Repsol properties (118,678) -- -- Acquisition of Shell Offshore properties -- (687,677) -- Acquisition of Shell Canada properties -- (517,815) -- Acquisition of British-Borneo interests, net of cash acquired -- (83,590) -- Acquisition of Novus subsidiaries, net of cash acquired Proceeds from sales of oil and gas properties Other, net NET CASH USED IN INVESTING ACTIVITIES -- (5,758) 26,271 155,226 (36,875) (18,937) (2,229,014) (1,769,751) (48,499) 194,147 2,967 (512,120) CASH FLOWS FROM FINANCING ACTIVITIES: Long-term borrowings Payments on long-term debt Dividends paid Issuance (repurchase) of preferred stock 1,125,981 1,602,871 (793,531) (1,075,821) 551,897 (556,141) (52,945) (42,264) (28,204) (2,613) 210,490 98,630 Issuance of common stock 465,306 455,381 1,240 Payments to acquire treasury stock (17,730) (15,603) (21,418) Cost of debt and equity transactions NET CASH PROVIDED BY FINANCING ACTIVITIES (838) 723,630 (4,843) 1,130,211 (544) 45,460 NET INCREASE (DECREASE) IN CASH AND CASH EQUIVALENTS 24,002 (1,366) CASH AND CASH EQUIVALENTS AT BEGINNING OF YEAR CASH AND CASH EQUIVALENTS AT END OF YEAR 13,171 14,537 9,686 37,173 13,171 14,537 Source: Apache 2000 10-K 12 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. 4,851 For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 4 Apache's Revenues and Costs by Country for 2000 ($ thousands) United States Income Statement Information Oil and Gas Production Revenues Operating Expenses: Depreciation, depletion and amortization Operating costs Operating Income (Loss) Canada Egypt Australia Other Int'l 1,374,941 331,503 360,772 223,543 -- 2,290,759 356,998 216,001 801,942 79,892 39,559 212,052 84,425 28,328 248,019 62,183 30,536 130,824 48 -(48) 583,546 314,424 1,392,789 Other Income (Expense): Equity in income of affiliates Other revenues Administrative, selling and other Financing costs, net Income Before Income Taxes Balance Sheet Information Total Long-Lived Assets Total Assets Additions to Long-Lived Assets Total 862 (7,717) (75,615) (106,638) 1,203,681 3,643,439 4,022,749 1,378,639 1,463,306 854,531 965,733 783,884 856,575 151,969 173,587 6,812,462 7,481,950 1,461,479 649,804 93,083 117,248 20,865 2,342,479 Source: Apache 2000 10-K This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. -13- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 5 Risk Management at Apache Apache's Gross Wells Drilled: 1998-2000 Exploratory Productive Dry Total Developmental Productive Dry Total 2000 United States Canada Australia Egypt Other International Total 5.8 1.0 5.0 1.4 -13.2 9.1 7.0 5.8 13.7 0.9 36.5 14.9 8.0 10.8 15.1 0.9 49.7 201.0 58.7 9.7 4.3 -273.7 41.6 11.7 1.6 --54.9 242.6 70.4 11.3 4.3 -328.6 1999 United States Canada Australia Egypt Other International Total 4.1 1.3 2.0 1.6 -9.0 8.2 2.3 5.4 1.2 1.6 18.7 12.3 3.6 7.4 2.8 1.6 27.7 59.1 26.2 2.6 15.6 0.5 104.0 4.8 12.1 0.2 1.2 -18.3 63.9 38.3 2.8 16.8 0.5 122.3 1998 United States Canada Australia Egypt Other International Total 9.9 16.2 3.5 5.6 -35.2 11.1 11.0 3.4 13.5 0.2 39.2 21.0 27.2 6.9 19.1 0.2 74.4 64.0 28.3 -11.9 0.2 104.4 18.8 6.1 -2.8 -27.7 82.8 34.4 -14.7 0.2 132.1 Source: Apache 2000 10-K 14 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Oil Futures Prices, Apache’s Issuances of Debt and Equity, and Apache’s Property Acquisition’s West Texas Intermediate Futures Prices Public Issue of Debt or Equity Bank Debt Property acquisitions of >$200 mil. and <$400 mil. Property acquisitions of >$400 mil. Source: West Texas Intermediate futures prices from Datastream. Debt, equity, and acquisitions information from Thompson Financial. This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. Ja n00 Ja n99 Ja n98 Ja n97 Ja n96 Ja n95 Ja n94 Ja n93 Ja n92 Ja n91 Ja n90 Ja n89 Ja n88 Ja n87 Ja n86 0 Phillips Petro. $490 M C & W $321 M $468 M F.C.E. $630 M Oxy Petro $365 M $269 M Shell Canada $519 M 1 Standard deviation below mean $99 M Shell Oil $743 M $620 M $149 M $100 M $148 M Ampolex Ltd. $390 M $148 M $168 M $162 M $149 M $417 M Phoenix Res. $428 M $99 M $180 M $203 M DeKalb Energy $240 M $126 M $100 M $195 M 10 $295 M 20 1 Standard deviation above mean MW Petro. $540 M 30 $60 M $ per barrel 40 Occidental Petro. $222 M $122 M $90 M 50 $150 M Oil Futures Prices, Apache's Issuances of Debt and Equity, and Apache's Property Acquisitions $81 M Exhibit 6 -15- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 7 Stock Performance of Apache Relative to Major and Secondary Oil Companies Indices and Oil Futures Prices Stock Performance of Apache Relative to Major and Secondary Oil Company Indices and Oil Futures Prices 6 Scaled Price 5 4 3 2 1 Dow Jones Major Oil Companies Dow Jones Secondary Oil Companies Apache Stock West Texas Intermediate Oil Futures Price Source: Price data from Datastream This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. 01 Ja n- 00 Ja n- 99 Ja n- 98 Ja n- 97 Ja n- 96 Ja n- 95 Ja n- 94 Ja n- 93 nJa Ja n- 92 0 -16- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 8 Firm Characteristics of Apache and Other Oil Companies R-squared from Market Model Annual Company Independents Anadarko Petroleum Apache Barrett Resources Burlington Resources EOG Resources Louis Dreyfus Occidental Ocean Energy Pioneer Natural Resources Union Pacific Resourcesa Vastar Resourcesa Majors Chevron Exxon Mobil Texaco b Beta Volatility c Regression d Sales (MM$) Cash (MM$) Market Value Equity (MM$) Long-Term Debt (MM$) 10.2% 6.0% 4.4% 6.7% 4.5% 10.1% 5.8% 6.9% 5.3% 5.0% 4.7% 5,686 2,291 376 3,147 1,482 490 13,574 1,074 853 1,728 1,895 199 37 25 132 20 3 97 23 26 124 41 17,782 8,662 1,897 10,886 6,386 2,002 8,972 2,907 1,938 3,158 5,761 3,984 2,218 359 2,301 859 607 5,445 1,033 1,579 2,800 975 18% 20% 18% 17% 12% 23% 38% 26% 45% 47% 14% BBB+ ABB+ ABBB+ BBB BBBBB+ BB+ BBBBBB+ 0.51 0.32 0.19 27% 26% 31% 14.6% 10.4% 1.8% 46,532 206,083 50,100 2,630 7,081 253 54,130 301,238 33,607 6,232 13,441 7,191 10% 4% 18% AA AAA A+ Correlation between oil and gas price changes 0.20 Source: CRSP, Bloomberg, Thompson Financial, Datastream a Year-end 2000 except Vastar Resources, Union Pacific Resources which are year-end 1999. b Beta calculated using 5 years of monthly returns from 1996-2000. Annual volatility and correlation using daily returns from January-December 2000. R-squared from regression equation with firm return as dependent variable, market return as independent variable. e Long-term debt as a percent of firm value, where firm value is book debt + market equity. f Ratingf 52% 52% 50% 46% 49% 51% 39% 62% 48% 60% 30% 57% 56% d % Debt 0.82 0.65 0.67 0.60 0.56 1.05 0.49 0.92 0.83 0.79 0.50 Annual Oil Price Volatility in 2000 Annual Gas Price Volatility in 2000 c S&P Debt e As of January, 2001. This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. -17- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 9 Historical Volatility of Oil and Gas Futures Price Changes and Apache Stock Price Changes Historical Volatility of Oil and Gas Futures Price Changes and Apache Stock Price Changes 140% 120% 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% Ja n9 M 6 ay -9 Se 6 p9 Ja 6 n9 M 7 ay -9 Se 7 p9 Ja 7 n9 M 8 ay -9 Se 8 p9 Ja 8 n9 M 9 ay -9 Se 9 p9 Ja 9 n0 M 0 ay -0 Se 0 p00 0% Gas price volatility Oil price volatility Apache volatility Source: Oil and gas future prices from NYMEX. Apache stock price data from Datastream. This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. -18- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache Exhibit 10 201-113 Sensitivity of the Firm's Stock Returns to Changes in Oil and Gas Futures Prices: Regression I: Firm Return = α + β 1(% change in oil price) + β 2(% change in gas price) Panel A: Independent Oil Firms Regression Coefficients (t-statistics in parentheses) Name of Firm Intercept α) (α % Change in Oil Price Sensitivity β 1) (β % Change in Gas Price Sensitivity β 2) (β Adjusted R2 from Regression I Anadarko Petroleum 0.01 (0.62) 0.42 (3.22) 0.32 (4.36) 38.7% Apache 0.01 (0.47) 0.24 (1.81) 0.42 (5.58) 40.7% Barrett Resources 0.01 (0.33) 0.19 (1.09) 0.46 (4.69) 30.5% Belco Oil & Gas Corp. -0.01 (-0.52) 0.12 (0.57) 0.27 (2.28) 7.8% Burlington Resources 0.00 (-0.33) 0.10 (0.87) 0.40 (6.30) 41.0% Devon Energy Corp. 0.01 (0.42) 0.15 (1.19) 0.43 (6.10) 42.9% EOG Resources 0.00 (0.34) 0.09 (0.62) 0.44 (5.52) 36.0% Louis Dreyfus 0.01 (0.79) 0.09 (0.49) 0.50 (4.88) 30.0% Magnum Hunter Resources 0.02 (1.10) -0.08 (-0.37) 0.41 (3.37) 14.2% Newfield Exploration Co. 0.01 (0.77) 0.52 (3.87) 0.37 (4.86) 45.7% 0.00 (-0.06) 0.37 (2.44) 0.36 (4.08) 31.9% 0.00 (0.19) 0.06 (0.51) 0.20 (2.75) 10.9% -0.01 (-0.78) 0.50 (3.02) 0.53 (5.56) 46.0% 0.01 (0.60) 0.57 (3.31) 0.49 (4.96) 46.0% Pioneer Natural Resources -0.01 (-0.59) 0.38 (2.07) 0.52 (4.93) 36.8% Range Resources Corp. -0.01 (-0.46) 0.86 (3.08) 0.62 (3.88) 34.3% Noble Affiliates Inc. Occidental Ocean Energy Patina Oil & Gas Corp. 19 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache Exhibit 10 (continued) Panel A: Independent Oil Firms (continued) Regression Coefficients (t-statistics in parentheses) Intercept α) (α Name of Firm St. Mary Land & Exploration Co. % Change in Oil Price Sensitivity β 1) (β % Change in Gas Price Sensitivity β 2) (β 2 Adjusted R from Regression I 0.02 (1.04) 0.28 (1.71) 0.45 (4.71) 33.2% 0.00 (-0.12) 0.25 (1.10) 0.41 (2.88) 18.1% Unocal Corp. 0.00 (-0.1) 0.22 (2.23) 0.22 (3.95) 29.7% Vastar Resources 0.02 (1.35) 0.06 (0.45) 0.27 (2.93) 15.4% Vintage Petroleum Inc. 0.00 (0.17) 0.89 (4.04) 0.45 (3.56) 38.6% Union Pacific Resources Panel B: Major Oil Firms Chevron 0.01 (0.94) 0.08 (1.01) 0.12 (2.54) 11.1% Exxon Mobil 0.01 (2.18) 0.06 (0.92) 0.05 (1.35) 2.5% Texaco 0.01 (0.71) 0.16 (1.78) 0.12 (2.36) 14.1% Panel C: Firms outside the oil and gas industry Bethlehem Steel Corp -0.02 (-1.2) -0.01 (-0.03) -0.13 (-1.21) 0.0% Borg Warner Inc 0.01 (0.89) -0.08 (-0.57) 0.01 (0.13) 0.0% Ford 0.02 (2.16) -0.20 (-1.65) -0.02 (-0.36) 2.2% General Electric 0.03 (2.56) 0.04 (0.45) 0.01 (0.21) 0.0% Goodyear Tire -0.01 (-0.65) -0.09 (0.67) 0.15 (1.90) 2.8% Pepsi Co. 0.01 (1.17) -0.14 (-1.29) 0.10 (1.57) 2.3% Wal-Mart 0.04 (3.14) -0.24 (-2.03) 0.03 (-0.44) 5.0% Source: Datastream, Center for Research in Security Prices, NYMEX. Regressions employ monthly observations during the 1996-2000 period. *During 1996-2000, the correlation between the percentage change in oil prices and the percentage change in gas prices was 0.20. The annual volatility of oil price changes was 57%, and the annual volatility of gas price changes was 56%. 20 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. Risk Management at Apache 201-113 Exhibit 11 Sensitivity of the Firm's Stock Returns to Changes in Oil and Gas Futures Prices and Market Movements: Regression II: Firm Return = α + β 1(% change in oil price) + β 2(% change in gas price) + β 3(market return) Panel A: Independent Oil Firms Regression Coefficients (t-statistics in parenthesis) Name of Firm Intercept α) (α % Change in Oil Price Sensitivity (β β 1) % Change in Gas Price Sensitivity (β β 2) Market Sensitivity (β β 3) Adjusted R2 from Regression II Anadarko Petroleum 0.00 (-0.13) 0.37 (3.03) 0.33 (4.70) 0.72 (2.90) 45.9% Apache 0.00 (-0.13) 0.20 (1.57) 0.43 (5.83) 0.59 (2.29) 44.9% Barrett Resources 0.00 (-0.16) 0.15 (0.87) 0.47 (4.83) 0.63 (1.85) 33.3% Belco Oil & Gas Corp. -0.02 (-1.16) 0.05 (0.28) 0.28 (2.44) 0.96 (2.44) 15.5% Burlington Resources -0.01 (-1.01) 0.06 (0.58) 0.40 (6.38) 0.58 (2.57) 46.4% Devon Energy Corp. 0.00 (-0.32) 0.10 (0.88) 0.44 (6.51) 0.66 (2.76) 49.1% EOG Resources 0.00 (-0.17) 0.05 (0.38) 0.44 (5.69) 0.54 (1.94) 39.0% Louis Dreyfus 0.00 (0.01) 0.02 (0.13) 0.50 (5.23) 1.05 (3.13) 39.5% Magnum Hunter Resources 0.01 (0.54) -0.14 (-0.65) 0.42 (3.52) 0.89 (2.11) 19.2% Newfield Exploration Co. 0.00 (-0.12) 0.46 (3.77) 0.38 (5.42) 0.89 (3.59) 55.2% Noble Affiliates Inc. -0.01 (-0.68) 0.33 (2.21) 0.36 (4.29) 0.70 (2.36) 37.1% Occidental 0.00 (-0.31) 0.03 (0.27) 0.20 (2.86) 0.47 (1.92) 14.9% Ocean Energy -0.02 (-1.44) 0.45 (2.81) 0.53 (5.86) 0.80 (2.48) 50.5% Patina Oil & Gas Corp. 0.00 (-0.08) 0.51 (3.11) 0.50 (5.35) 0.91 (2.81) 52.4% -0.02 (-1.1) 0.34 (1.85) 0.53 (5.10) 0.72 (1.97) 39.9% 34.6% Pioneer Natural Resources Range Resources Corp. -0.02 0.82 0.62 0.62 (-0.73) (2.92) (3.91) (1.10) 21 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Risk Management at Apache Exhibit 11 (continued) Panel A: Independent Oil Firms (continued) Regression Coefficients (t-statistics in parentheses) Name of Firm St. Mary Land & Exploration Co. Intercept α) (α % Change in Oil Price Sensitivity β 1) (β % Change in Gas Price Sensitivity β 2) (β Market Sensitivity β 3) (β 2 Adjusted R from Regression II 0.00 (0.30) 0.22 (1.43) 0.45 (5.09) 0.94 (2.95) 41.3% Union Pacific Resources -0.01 (-0.62) 0.24 (1.07) 0.39 (2.81) 0.66 (1.49) 20.1% Unocal Corp. -0.01 (-0.57) 0.20 (2.02) 0.23 (4.07) 0.36 (1.80) 32.4% Vastar Resources 0.01 (0.83) 0.05 (0.36) 0.26 (2.82) 0.39 (1.36) 16.7% Vintage Petroleum Inc. -0.01 (-0.7) 0.80 (3.93) 0.46 (3.94) 1.37 (3.33) 47.9% Chevron 0.00 (0.14) 0.05 (0.67) 0.12 (2.81) 0.49 (3.22) 23.8% Exxon Mobil 0.01 (1.55) 0.04 (0.64) 0.05 (1.47) 0.32 (2.52) 11.0% Texaco 0.00 (0.47) 0.15 (1.66) 0.12 (2.37) 0.15 (0.83) 13.6% Panel B: Major Oil Firms Panel C: Firms outside the oil and gas industry Bethlehem Steel Corp -0.04 (-2.36) -0.09 (-0.55) 0.12 (-1.27) 1.33 (4.03) 20.8% Borg Warner Inc 0.00 (0.00) -0.13 (-1.08) 0.02 (0.22) 0.88 (3.59) 15.1% Ford 0.01 (1.34) -0.24 (-2.25) -0.01 (-0.24) 0.85 (4.06) 23.7% General Electric 0.01 (1.52) -0.02 (-0.34) 0.02 (0.46) 1.09 (7.65) 49.2% Goodyear Tire -0.02 (-1.4) -0.14 (-1.06) 0.16 (2.08) 0.76 (2.83) 13.6% Pepsi Co. 0.00 (0.01) -0.20 (-2.21) 0.10 (2.02) 0.95 (5.18) 33.1% Wal-Mart 0.03 (2.39) -0.29 (-2.39) 0.02 (0.41) 0.79 (3.65) 22.2% Source: Datastream, Center for Research in Security Prices, NYMEX. Regressions employ monthly observations during the 1996-2000 period. *During 1996-2000, the correlation between the percentage change in oil prices and the percentage change in gas prices was 0.25. The annual volatility of oil price changes was 57%, and the annual volatility of gas price changes was 56%. 22 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 12 Oil and Gas Producers' Hedges in Place for Years 2000 and 2001 Panel A: Year 2000 Hedges Crude & Natural Gas Liquids Average Percent of Hedged Price Production per BBL Natural Gas Average Percent of Hedged Price Production per MCF Total Production: Oil & Gas Percent of Average Total Effect on Total Hedged Price Cash Flow per Production per BOE Share (%/share) Anadarko Petroleum Corp. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Apache Corp. 17% $21.75 7% $3.35 12% $21.24 -3% Barrett Resources Corp. 0% - 48% $2.95 45% $17.69 -18% Belco Oil & Gas Corp. 91% $19.40 65% $2.60 75% $17.33 -32% Burlington Resources Inc. 18% $20.50 34% $2.50 31% $15.62 -14% Devon Energy Corp. 0% - 12% $1.96 8% $11.74 -3% EOG Resources, Inc. 8% $20.00 0% - 1% $20.00 -1% Magnum Hunter Resources 62% $24.44 12% $2.45 26% $21.08 -17% Newfield Exploration Co. 50% $22.02 39% $3.00 42% $19.23 -14% Noble Affiliates, Inc. 16% $21.73 0% - 5% $21.73 -2% Ocean Energy, Inc. 64% $21.19 25% $2.85 44% $19.98 -16% Patina Oil & Gas Corp. 78% $21.88 60% $2.72 64% $17.87 -26% Range Resources Corp. 50% $23.65 69% $2.69 64% $17.65 -27% Santa Fe Snyder Corp. 46% $21.97 6% $3.30 26% $21.70 -7% St. Mary Land & Exploration Co. 54% $21.91 39% $2.43 43% $16.98 -16% Union Pacific Resources Group 61% $21.09 56% $2.66 58% $17.91 -17% Unocal Corp. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Vintage Petroleum, Inc. 37% $25.28 0% - 26% $25.28 -5% Average of Large Capitalization Firms 23% 18% 20% -8% Average of Small Capitalization Firms 71% 53% 58% -23% This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. -23- For the exclusive use of C. MIB Trieste School of Management, 2024. 201-113 Exhibit 12 (continued) Panel B: Year 2001 Hedges Natural Gas Crude & Natural Gas Liquids Total Production: Oil & Gas Percent of Production Average Hedged Price per BBL Percent of Production Average Hedged Price per MCF Percent of Total Effect on Average Total Hedged Price Cash Flow per per BOE Production Share (%/share) Anadarko Petroleum Corp. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Apache Corp. 7% $18.80 0% - 3% $18.80 -1% Barrett Resources Corp. 0% - 38% $2.93 36% $17.60 -2% Belco Oil & Gas Corp. 59% $19.80 65% $2.65 63% $17.29 -29% Burlington Resources Inc. 16% $20.50 10% $2.40 11% $16.16 -6% Devon Energy Corp. 0% - 5% $1.84 3% $11.04 -2% EOG Resources, Inc. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Magnum Hunter Resources 0% - 0% n/a 0% n/a 0% Newfield Exploration Co. 19% $21.65 16% $2.98 17% $18.97 -5% Noble Affiliates, Inc. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Ocean Energy, Inc. 8% $17.00 0% - 4% $17.00 -2% Patina Oil & Gas Corp. 34% $23.68 11% $3.37 16% $21.81 -5% Range Resources Corp. 0% - 6% $3.03 5% $18.18 -3% Santa Fe Snyder Corp. 16% $16.87 0% - 8% $16.87 -4% St. Mary Land & Exploration Co. 15% $21.26 29% $3.03 25% $18.65 -7% Union Pacific Resources Group 30% $25.25 1% $2.40 11% $24.85 0% Unocal Corp. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Vintage Petroleum, Inc. 0% - 0% - 0% n/a 0% Average of Large Capitalization Firms 8% 4% 5% -2% Average of Small Capitalization Firms 28% 25% 26% -9% Source: Deutsche Bank Alex. Brown Analyst Report July 14, 2000 This document is authorized for use only by CONSORZIO MIB Trieste School of Management in 2024. -24-