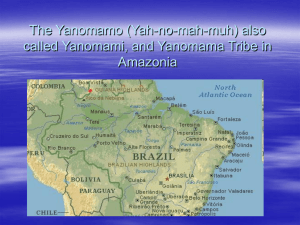

Yanomami: The Fierce Controversy & What We Can Learn

advertisement