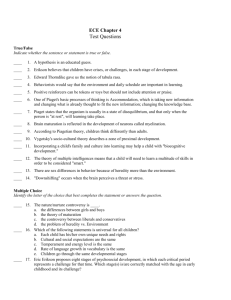

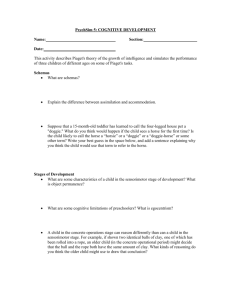

Piaget Stages of Development Concrete Operational Stage Piaget's four stages of intellectual (or cognitive) development are: At this time, elementary-age and preadolescent children -- ages 7 to 11 -- show logical, concrete reasoning. Sensorimotor. Birth through ages 18-24 months Preoperational. Toddlerhood (18-24 months) through early childhood (age 7) Concrete operational. Ages 7 to 11 Formal operational. Adolescence through adulthood Sensorimotor Stage During the early stages, according to Piaget, infants are only aware of what is right in front of them. They focus on what they see, what they are doing, and physical interactions with their immediate environment. Because they don't yet know how things react, they're constantly experimenting. They shake or throw things, put things in their mouth, and learn about the world through trial and error. The later stages include goal-oriented behavior that leads to a desired result. Between ages 7 and 9 months, infants begin to realize that an object exists even though they can no longer see it. This important milestone -- known as object permanence -- is a sign that memory is developing. After infants start crawling, standing, and walking, their increased physical mobility leads to more cognitive development. Near the end of the sensorimotor stage (18-24 months), infants reach another important milestone -- early language development, a sign that they are developing some symbolic abilities. Preoperational Stage During this stage (toddler through age 7), young children are able to think about things symbolically. Their language use becomes more mature. They also develop memory and imagination, which allows them to understand the difference between past and future, and engage in make-believe. Children's thinking becomes less focused on themselves. They're increasingly aware of external events. They begin to realize that their own thoughts and feelings are unique and may not be shared by others or may not even be part of reality. But during this stage, most children still can't think abstractly or hypothetically. Formal Operational Stage Adolescents who reach this fourth stage of intellectual development -- usually at age 11plus -- are able to use symbols related to abstract concepts, such as algebra and science. They can think about things in systematic ways, come up with theories, and consider possibilities. They also can ponder abstract relationships and concepts such as justice. Concepts of Piaget's Stages of Development Along with the stages of development, Piaget's theory has several other main concepts. Schemas are thought processes that are essentially building blocks of knowledge. A baby, for example, knows that it must make a sucking motion to eat. That's a schema. Assimilation is how you use your existing schemas to interpret a new situation or object. For example, a child seeing a skunk for the first time might call it a cat. Accommodation is what happens when you change a schema, or create a new one, to fit new information you learn. The child accommodates when they understand that not all furry, four-legged creatures are cats. Equilibrium happens when you're able to use assimilation to fit in most of the new information you learn. So you're not constantly adding new schemas. But their thinking is based on intuition and still not completely logical. They cannot yet grasp more complex concepts such as cause and effect, time, and comparison. An Overview of the Gestalt Laws of Perceptual Organization 1 These are just a few real-life examples of the six Gestalt principles or laws, which are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Law of similarity Law of prägnanz Law of proximity Law of continuity Law of closure Law of common region Law of Continuity The law of continuity holds that points that are connected by straight or curving lines are seen in a way that follows the smoothest path. In other words, elements in a line or curve seem more related to one another than those positioned randomly. Law of Closure According to the law of closure, we perceive elements as belonging to the same group if they seem to complete some entity.1 Our brains often ignore contradictory information and fill in gaps in information. In the image at the top of the page, you probably see the shape of a diamond because your brain fills in the missing gaps in order to create a meaningful image. Law of Common Region Law of Similarity The law of similarity states that similar things tend to appear grouped together. Grouping can occur in both visual and auditory stimuli. The Gestalt law of common region says that when elements are located in the same closed region, we perceive them as belonging to the same group. 1 Look at the last image at the top of the page. The circles are right next to each other so that the dot at the end of one circle is actually closer to the dot at the end of the neighboring circle. But despite how close those two dots are, we see the dots inside the circles as belonging together. Creating a clearly defined boundary can overpower other Gestalt laws such as the law of proximity. In the image at the top of this page, for example, you probably see two separate groupings of colored circles as rows rather than just a collection of dots. Law of Prägnanz The law of prägnanz is sometimes referred to as the law of good figure or the law of simplicity. This law holds that when you're presented with a set of ambiguous or complex objects, your brain will make them appear as simple as possible.3 For example, when presented with the Olympic logo, you see overlapping circles rather than an assortment of curved, connected lines. The word prägnanz is a German term meaning "good figure." Law of Proximity According to the law of proximity, things that are close together seem more related than things that are spaced farther apart.4 In the image at the top of the page, the circles on the left appear to be part of one grouping while those on the right appear to be part of another. Because the objects are close to each other, we group them together. Thorndike Theory The law of effect states that behaviors followed by pleasant or rewarding consequences are more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by unpleasant or punishing consequences are less likely to be repeated. The principle was introduced in the early 20th century through experiments led by Edward Thorndike, who found that positive reinforcement strengthens associations and increases the frequency of specific behaviors. 2 The law of effect principle developed by Edward Thorndike suggested that: Frequent trials allow errors to be corrected and neural pathways related to the knowledge/skill to become more engrained. “Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation (Gray, 2011, p. 108–109).” As associations are reinforced through drill and rehearsal, retrieval from long term memory also becomes more efficient. In sum, repeated exercise of learned material cements retention and fluency over Additional Laws Of Learning In Thorndike’s Theory time. Forgetting happens when such connections are not actively preserved through practice. Thorndike’s theory explains that learning is the formation of connections between stimuli and responses. The laws of learning he proposed are the law of readiness, the law of exercise, and the law of effect. Law of Readiness The law of readiness states that learners must be physically and mentally prepared for learning to occur. This includes not being hungry, sick, or having other physical distractions or discomfort. Mentally, learners should be inclined and motivated to acquire the new knowledge or skill. If they are uninterested or opposed to learning it, the law states they will not learn effectively. Learners also require certain baseline knowledge and competencies before being ready to learn advanced concepts. If those prerequisites are lacking, acquisition of new info will be difficult. Overall, the law emphasizes learners’ reception and orientation as key prerequisites to successful learning. The right mindset and adequate foundation enables efficient uptake of new material. Law of Exercise The law of exercise states that connections are strengthened through repetition and practice. 3