DIETARY PRACTICE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN IN JIMMA TOWN HEALTH CENTERS, JIMMA, SOUTH WEST ETHIOPIA

advertisement

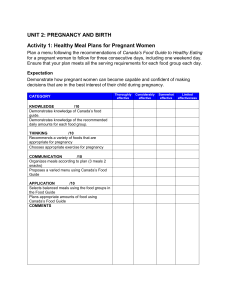

DIETARY PRACTICE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN IN JIMMA TOWN HEALTH CENTERS, JIMMA, SOUTH WEST ETHIOPIA BY: DURETI KEBEDE A RESEARCH THESIS SUBMITTED TO JIMMA UNIVERSITY, INSTITUTE OF HEALTH, AND COLLAGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE, SCHOOL OF MIDWIFERY, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF MIDWIFERY. SEP, 2022 JIMMA, ETHIOPIA I JIMMA UNIVERSITY, INSTITUTE OF HEALTH, COLLAGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE, SCHOOL OF MIDWIFERY DIETARY PRACTICE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN IN JIMMA TOWN HEALTH CENTERS, JIMMA, SOUTH WEST ETHIOPIA BY: Dureti Kebede ADVISOR: _Enyew Melkamu SEP, 2022 JIMMA, ETHIOPIA II Contents ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................................. V Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. VI Lists of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ VII CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Statement of the problem ................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 Significance of the study ................................................................................................................. 4 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER THREE; OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................... 8 3.1 General Objective ........................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Specific Objective ........................................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER FOUR: METHODS AND MATERIALS .............................................................................. 9 4.1 Study area............................................................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.2 Study period .................................................................................................................................... 9 4.3 Study design .................................................................................................................................... 9 4.4 Population ........................................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.5. Inclusion and exclusion criteria ......................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.6. Sample size and sampling techniques .......................................................................................... 10 4.7. Sampling technique ............................................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.8. Data collection tool and procedures ............................................................................................. 10 4. 9. Study variables .................................................................. Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.10. Operational definition and measurements................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.11. Ethical consideration ........................................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 4.12. Dissemination plan........................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. 5. Result ........................................................................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants ............................................................. 13 III Table 2: Knowledge of the participants on dietary practice ................................................................... 15 Table 3: Dietary practice of pregnant mothers........................................................................................ 15 5.1. Discussion ........................................................................................................................................ 25 5.2. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................................... 25 5.3. Recommednations ............................................................................................................................ 26 6. REFERENCES ......................................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. Annex: - Questionnaire ................................................................. Ошибка! Закладка не определена. IV ABSTRACT Background: Nutrition is a fundamental pillar of human life, health and development throughout the entire life span. The nutrition requirement varies with respect of age, gender and physiologic change like pregnancy. Pregnancy is a critical life in women’s life when the expectant mother needs optimal nutrients to support the developing fetus. The diet of a woman before and during pregnancy has immense influence on the course of pregnancy and health of a child both after delivery and in the future. Lack of dietary knowledge and the knowledge about consequences of malnutrition among future mothers may result in a lot of dietary indiscretion, which in turn can cause deficiency or excess of energy and particular nutrients, as well as abnormal course of pregnancy. Hence, for keeping a proper diet during pregnancy a woman must not only know the healthy eating guidelines, but also realize how a diet influences the course of pregnancy and child's health. Objectives: The aim of this study is to assess the dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women visiting ANC follow up at Jimma town health centers, 2022. Methods: An institutional based cross sectional study was conducted from March 10- 30, 2022 among 239 pregnant women attending ANC clinics in health centers of Jimma town. Convenient non probability sampling procedure was used to select the study participants. The data was collected using semi- structured questionnaire. The association between explanatory variables and dietary practices was determined by carrying out chi square test using SPSS software. Pvalues of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Result: Conclusion: Keywords: Nutrition, Practice, Pregnancy, Jimma V Acknowledgements First and for most thanks to the Almighty GOD who is my power and strength. I would like to express my deepest and heartfelt gratitude to my advisor Mr.Eneyew for his continuous guidance and unreserved support throughout my work. I would like to thank Jimma University for providing me this opportunity to maintain & continue my academic pursuits. I also thank the university, particularly college of public health & medical science and CBE office for providing me materials needed for this research paper. VI Lists of abbreviations ACOG- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology ANC – Antenatal care CBE-Community Based Education EC-Ethiopian calendar FAO- Food and Agriculture organization HCG-Human Chorionic Gonadotrophic hormone IM – Institute of Medicine JUSH – Jimma University Specialized Hospital MCH – Maternal and Child Health OL-obstructed labor SNNP – Southern Nations, Nationality and People UNICEF – United Nations International Children Educational Fund USAID-United State Agency for International Development WHO – World Health Organizations VII CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND Pregnancy is a critical period in the lifecycle during which additional nutrients are required to meet the metabolic and physiological demands as well as the increased requirements of the growing fetus(1). A well balanced diet is a basic component of good health at all times, especially for pregnant women. Pregnant women require varied diets and increased nutrient intake to cope with the extra needs during pregnancy. For healthy pregnancy, the mother’s diet needs to be balanced and nutritious, involving the right balance of proteins, carbohydrates and fats and consuming a wide variety of vegetables and fruits(2). Dietary practices play a significant role in determining the long-term health status of both the expectant mother and the growing fetus. Improper dietary practices of pregnant women have apparently led to increased rates of poor birth outcomes(3). Appropriate dietary practice plays a vital role in reducing some of the health risks associated with pregnancy such as risk of fetal and infant mortality, intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight and premature births, decreased birth defects, cretinism, poor brain development and risk of infection. In most developing countries, maternal under nutrition during pregnancy is persistent and an important contributor to morbidity, mortality, and poor birth outcomes(4). Poor nutritional status is common in developing countries, often resulting in pregnancy complications and poor obstetric outcomes. Pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are at particular nutritional risk as a result of poverty, food insecurity, political and economic instabilities, frequent infections, frequent pregnancies and bad dietary practices like restriction of important food groups during pregnancy due to various forms of taboos, misconceptions, and cultural beliefs towards certain foods exist in various countries and hinder the pregnant women from consuming diversified/nutritionally rich food groups(5, 6). Diets of pregnant women in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are monotonous, low quality and predominantly plant-based with little consumption of micronutrient-dense animal-source foods, fruits, and vegetables (7, 8). Studies have shown that there is a strong positive relationship between the nutritional status of a pregnant woman, the growth and development of the fetus(9), the birth outcomes (10), and childhood morbidity and mortality(11). Pregnant women who eat a balanced diet have fewer complications during pregnancy and labor, and they are more likely to deliver live, normal, and healthier babies(12). On the other hand, pregnant women’s poor nutritional status results in adverse birth outcomes like low birth weight, preterm delivery and intrauterine growth retardation. 1 The consequences of micronutrient malnutrition affect not only the health and survival of women but also their children (13). The use of dietary supplements and fortified foods should be encouraged for pregnant women to ensure adequate supply of nutrients for both mother and fetus(14).To alleviate nutritionrelated health problem, Ethiopian government implemented different intervention programs such as linking with maternal continuum care, micro-nutrients supplementation to pregnant mothers, implementing packages of Health Extension Program and nutrition education like dietary diversification and minimum acceptable diet(15). Dietary diversity refers to an increase in the variety of foods across and within food groups consumed by each woman over a given reference period which can promote good health and physical and mental development of women(16). It is a qualitative measure of food consumption, used as a proxy of micronutrient adequacy at an individual level(17). Low dietary diversity is one of the most important causes of micronutrient deficiencies, also leading to macronutrient shortages (18). Minimum acceptable diet is a composite of women fed with a minimum dietary diversity and a minimum meal frequency. Caloric intake should increase by approximately 300 kcal/day during pregnancy. This value is derived from an estimate of 80,000 kcal needed to support a full-term pregnancy and accounts not only for increased maternal and fetal metabolism but for fetal and placental growth. Dividing the gross energy cost by the mean pregnancy duration (250 days after the first month) yields the 300 kcal/day estimate for the entire pregnancy(19, 20). However, energy requirements are generally the same as non-pregnant women in the first trimester and then increase in the second trimester, estimated at 340 kcal and 452 kcal per day in the second and third trimesters, respectively. Furthermore, energy requirements vary significantly depending on a woman’s age, BMI, and activity level. Caloric intake should therefore be individualized based on these factors(19). Pregnant women need 1000- 1,300 milligrams of calcium, 27 milligrams Iron, 220 micrograms Iodine, (750-770 micrograms Vitamin A , 8085 milligrams Vitamin C and 600 international units of Vitamin D (21, 22). 2 1.2 Statement of the problem Globally about 303,000 mothers died from pregnancy and childbirth related causes in 2015 and majority (99%) of the deaths occurred in developing countries, with sub-Saharan Africa alone accounting for roughly 66%. But the target is to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births at 2030 (23, 24). Ethiopia is also one of the subSaharan country with high Maternal mortality rate 412 deaths per 100,000 live births and child mortality rate 67 per 1000 live birth(25). Women tend not to report for care until the second trimester, thus the initial critical period of the first 1000 days are frequently missed(26). This presents a major limitation to ensuring adequate uptake of interventions for a reasonable duration, even though factors like nutritional status are crucial from the time of conception for placentation, organogenesis, prevention of congenital birth defects, and fetal growth. Many of women became pregnant each year, most of them in developing countries suffer from ongoing nutritional deficiency, repeated infections and the long term causalities consequences of under nutrition during their own child hood. Many women suffer from a combination of chronic protein energy deficiency, poor weight gain, pregnancy anemia and other micronutrients deficiency as well as infections like HIV and malaria. These along with inadequate dietary practice contribute to high rate of maternal morbidity, mortality and poor birth outcomes. Adequate nutrient intake during pregnancy was found to reduce the risk for low birth weight (19%), small-for gestational-age births (8%), preterm birth by 16%, and infant mortality by 15% in those highly adhered to the regimen. In underweight women, multiple micronutrient supplementation initiation before 20 weeks’ gestation decreased the risk of preterm birth by 11% (27, 28). Antenatal healthy diet initiation in pregnancy and high adherence to multiple micronutrients supplements also provided greater overall benefits (10, 29). However, the burden of nutritional deficiency among pregnant women is still high especially in n subSaharan Africa (30-32). For instance, findings from Ethiopia also showed that 60.7% of pregnant women had history of poor dietary practices (33). A number of negative health consequences occur as a result of poor dietary practice during pregnancy. For instance, despite the global target is to reduce anaemia in women of reproductive age by 50% by 2025 (34), it affects 29% of pregnant women (35). Worldwide, more than a third of women are estimated to have folic acid deficiency(36). Also, in Ethiopia, about 31.8% of pregnant women were anaemic(37), 31.8% were malnourished (38) and one 3 in every three women had folic acid deficiency (39). Evidence showed that in low- and middle-income countries, anaemia contributes to 18% of perinatal mortality, 19% of preterm births and 12% of low birth weight(40). In addition, a number adverse maternal and child health outcomes including miscarriage, preterm, low birth weight, still birth, congenital anomalies, impaired fetal growth, learning impairment and behavioral problems of the offspring as well as poorer pregnancy weight gain, maternal and child mortalities occur as a result poor dietary practices during pregnancy(41). Indeed, the nutrient intake of pregnant women has various consequences on the health and wellbeing of children, households, communities and the nation at large, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is a great determinant of survival and quality of life for the off-spring (30). Furthermore, on top of health impacts, it leads to reduction in women’s productivity, and has economic, and psychosocial impacts(42). Failure to address maternal nutrition during pregnancy leads to permanent impairment, and might also affect future generations (43)(44, 45). These can be due to inadequate dietary intake, limited diet diversity (vegetables and fruits), and changing lifestyles(46, 47). A malnourished mother will give birth to a malnourished child, then to a malnourished teenager, then to a malnourished pregnant woman, and so the cycle continues. Different policies, programs and strategies such as minimum acceptable diet, dietary diversity, micronutrient supplementation, nutritional counseling has been implemented in in different countries of the world in order to improve dietary practice during pregnancy(46, 48, 49). In addition, pregnant women should also eat foods rich in macro and micro nutrients such as brown rice, red meat, liver, poultry, egg yolk, legume, dark-green leafy vegetables, citrus fruits, beans, and peas (50). However, the world especially the developing countries have been far from achieving the plan to improve or ending all forms of malnutrition (51, 52). There were some evidences on the nutritional status of pregnant women (53-56). Different studies showed that prevalence of poor dietary practice during pregnancy were high in Ethiopia(57, 58). However, pregnant women’s dietary practice in the study area were under researched. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women attending public health facilities of Jimma zone, 2022 1.3 Significance of the study Information obtained from this study will help to evaluate knowledge and dietary practice of pregnant women who will have ANC visit at Jimma town public health centers. It may also 4 serves health professionals and health institutions to design appropriate intervention which contribute in the reduction of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality rate due to malnutrition related to inadequate intake of nutrients during the pregnancy and its complications. It informs experts to promote dietary practices by educating people. Findings from this study will potentially serve rethinking about maternal nutrition at policy, program and management levels. Furthermore, it will also makes an important empirical contribution to the growing body of literature. CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. Prevalence of Dietary Practice during Pregnancy Adequate nutrition is essential for a woman throughout her life cycle to ensure proper development and prepare the reproductive life of the woman. Pregnant women require varied diets and increased nutrient intake to cope with the extra needs during pregnancy. Poor dietary practice during pregnancy often leads to long-term, irreversible and detrimental consequences to the mother as well as the fetus(14) . Study conducted in Rawalpindi, Pakistan revealed that Change in food intake practices by increasing frequency of meal, the amount or both were reported by about 57.3% participants, 17.3% reported reduced intake, while 25.5% pregnant women had no change in food consumption. About 22% avoid taking some food during their pregnancy period, such as beef, chicken, egg, salt, fruits, fried food, milk, oil, rice, tea, and butter (59). Study conducted in Ogun state of Nigeria revealed that (46%) of pregnant women ate more than three times a day, 38% ate just three times while the rest respondents ate once or twice daily. This indicates that majority of the study participants (54%) they don’t have extra meal during pregnancy in the study area. Study conducted in Aleta Chuko District of South Nations Nationalities People Representatives (SNNPR), Ethiopia: The frequency of one additional food from any type of food within the last 24 hours was 8%. However, the frequency of regular fed 3times per day was 92%,(3, 59). The study conducted on pregnant women in Hadiya zone of southern Ethiopia indicates that over half 5 (65 %) avoided at least one type of food during pregnancy. According to this report milk and cheese were regarded as taboo foods by nearly half of the women (44.4%) followed by linseed and fatty meat (16%, 11.1%) respectively. Food restrictions to most foods were found to be more prevalent during the last trimester, except for linseed which was said to be prohibited throughout pregnancy(60). Study conducted in Gondar, east Wollega zone of Guto Gida District and in Bahir Dar town, Northwest Ethiopia showed that poor dietary practice of pregnant women were found to be 59.1%, 66.1% and 60.7% respectively, which indicates that majority of women’s had experienced poor dietary practice during their pregnancy. Concerning meal frequency, pregnant women in Gondar, about 89 (15.5%) of the respondents had meal frequency of 1-2 per day during their pregnancy. Majority of pregnant mothers, 445 (77.5%) had meal frequency of 3 -4 times per day. Concerning the meal frequency per day, most of the respondents of Guto Gida district pregnant women (66.1%) had meal frequency of 1-2 per day during their pregnancy. The rest (20.3%) and (13.6%) had diet frequency of meals 3- 4 and >5 per day respectively during their pregnancy for the nutritional practice assessing question. The result from Bahir Dar town study indicated that 203(33%) study participants avoid certain foods, about 61.7% skip their usual meal and the most commonly skipped meal was breakfast (33, 57, 58). Study conducted in Wondo Genet district of SNNPR revealed that, regarding meal frequency majority about three fourth (75.2 %) of the respondents had no additional meal during Pregnancy. Only 21.6 %of the subjects reported that they eat at least one additional meal during pregnancy. About 43.8% commonly skipped lunch and 24.2 % reported that they skip breakfast. Nearly all (98%) of the study participants used rock salt for food preparation (61). 2.2. Factors associated with dietary practice In Sudan, pregnant women often have restricted food intake mainly due to morning sickness which is prevented and treated by eating little and limited items of food: and due also to the belief that a large fetus causing obstructed labor will result from eating unrestricted amount of food. In Sokoto state of Nigeria, the untrained traditional midwifes advice pregnant women to avoid sugar and honey as they cause prolonged painful labor. They also advise pregnant ladies not to take local soda which is supposed to make the fetus slim(8). Qualitative study conducted in Arsi Negele, Ethiopia, stated that pregnant women did not change the amount and type of foods consumed to take into account their increased nutritional need 6 during pregnancy. The consumption of meat, fish, fruits, and some vegetables during pregnancy remained as low as the pre-pregnancy state, irrespective of the women’s income and educational status. However, the frequency and extent of the practice varied by maternal age, family composition, and literacy level(6, 8). The study conducted in Hadia Zone revealed that the reason for avoiding food during pregnancy was fear of difficulty during delivery (51%), disclosures of the fetus (20%) and fear of abortion (9.75%) are the main reasons. Study conducted in Guto Gida district of east wollega zone identified that family size and information about nutrition during pregnancy have strong statistical association with nutrition practices of mothers during pregnancy. Women who had no information about nutrition during pregnancy had 6.3 times more likely poor nutritional practice than women who had nutrition information during pregnancy (58, 60). Nutrition information on which foods to eat during pregnancy came from health care providers, husbands, mothers-in-law, friends, and neighbors, as well as the Internet and television, which mothers acknowledged as affecting choices of foods eaten during the antenatal period. Mothers most often reported valuing and trusting the advice from medical doctors, who provide routine antenatal care, on the “best” foods to eat and which foods to avoid during pregnancy(62). Study conducted in Gondar showed that there was statistically significant association between family income and dietary practices of mothers. This study also identified that educational status had strong statistical association with dietary practices of mothers during pregnancy. Beside these the study identified that information about nutrition during pregnancy and nutritional knowledge had strong statistical association with dietary practices of mothers during pregnancy(57). Similar study conducted in Behir Dar town revealed that husband income, ownership of radio, history of illness and dietary knowledge had significant association with dietary practices of pregnant women in the study area. Study conducted in Gambela town 2014, revealed that statistically significant association between Pregnant women who were from food insecure households and under nutrition(33, 63). The extra energy needed during pregnancy and lactation represents a small percentage 5% of total household food energy needs. However, when household food insecurity is persistent, even these small amounts of extra food may be unavailable. Even when enough food is available at the household level, the majority of women do not receive adequate nutrients intake during pregnancy. Key contributing factors, including entrenched poverty, gross food 7 insecurity, gender discriminatory food allocation, food avoidances, and lack of access to adequate health services, continue to challenge women’s health and nutritional practices(4). Similar Study conducted in Wondo Gent District of SNNPR state that the frequency of meal among the pregnant women in the study area was taking no additional meal was significantly associated with family size, growing khat, not growing vegetables and fruits, and no consumption of white vegetables and roots. Skipping meal was reported by the study participants, and it was significantly associated with family size and number of pregnancy(61). Nutrition deserves special attention during pregnancy because of the high nutrient needs and the critical role of appropriate nutrition for the mother and the foetus. Physiological adaptations during pregnancy partly shield the foetus from inadequacies in the maternal diet, but even so these inadequacies can have consequences for both the short and long-term health and development of the foetus. CHAPTER THREE; OBJECTIVES 3.1 General Objective To assess the dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma town health centers, Jimma zone, Oromia region, south west Ethiopia, 2022. 3.2 Specific Objective To describe dietary practices of pregnant women in Jimma town health centers, Jimma zone, Oromia region, south west Ethiopia, 2022. To identify associated factors with dietary practices of pregnant women at Jimma town health centers, Jimma zone, Oromia region, south west Ethiopia, 2022. 8 CHAPTER FOUR: METHODS AND MATERIALS 4.1. Study Area and Period The study was conducted from 15 April 2022 to 15 May 2022 in Jimma town the capital of Jimma zone which is 352 Km far from Addis Ababa. The climatic zone is “Woinadega” and has temperature that ranges from 20-30 oC and the average annual rainfall of 800-2500mm3 and altitude of 1750-2000m above sea level. There are two Public hospitals, four health centers and more than 15 private clinics providing health services in Jimma town. According to the 2022 report obtained from Jimma town health office, the total population of the town is estimated to be 224,565, of which 112911 were males and 111654 were females. A total of 7,792 pregnant women found in the Jimma town. 4.2 Study period The study was conducted from March 10-30, 2022. 4.3 Study design Institution based cross-sectional study was conducted. 4.3. Population 4.3.1 Source Population All pregnant women who visit MCH clinic for ANC follow up at Jimma town public health facilities. 9 4.3.2. Study Population Pregnant women who visit Jimma town public health facilities for ANC follow-up during the study period. 4.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria 4.4.1. Inclusion Criteria Available pregnant women will come for ANC follow up during the study period. 4.4.2. Exclusion Criteria Pregnant women who severely ill. Those who unable to communicate 4.6. Sample size and sampling techniques The sample is determined using single population proportion formula as follows: n = [(Z α/2)2∗p (1-p)]/d2 Where, n= sample size Z α/2= Standard score for 95% confidence level (1.96) P= 25.1% proportion dietary practice (23) d= 5% the margin of error n= (1.96)2∗0.251 (1−0.251)2/ (0.05)2 =216.38 ≈217 After adding 10% non-response rate= 22, the final sample size become= 239. 4.5 Sampling Techniques First, the public health facilities are stratified into hospital and health centers. Then among the four health centers two were selected by using simple random sampling technique. Of the two public hospitals found in the town, Shanen Gibe hospital was purposively included for representation. In this study the author excluded Jimma medical center as there are a number of client with referral, which may not represent the jimma town population. Second, the total sample was allocated proportionally to each selected health facilities based on number of pregnant women who attend ANC follow up at the select health facilities. Then, a systematic sampling technique was used and K-value was determined based on the total number pregnant women in the health facilities. In case when more than one pregnant women attending ANC follow up, a lottery method of simple random sampling technique was employed to select the first mother. Then, data was collected every K- value until the final sample size is achieved. 4.6. Data collection tool and procedures Interviewer-administered structured questionnaire was adapted from different literatures. The questionnaire consists of three main parts: socio demographic data, knowledge and dietary 10 practices. The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated to Afan Oromo and Amharic languages. Local language versions was used for data collection. Data collectors were those Midwives to their respective site who were assigned for their normal internship under the supervision of principal investigator. Some data was also being reviewed from the patient’s card. 4. 7. Study Variables Dependent variable: Dietary practice of pregnant mothers Independent variable Socio-demographic factors:- which are combination of social and demographic factors like; Maternal age, country of birth, marital status, education level and occupation Socio-income factors: - are the factors arising from income level. This will show social economic status Individual factors:- it is the individual life standard and property of individual influencing pregnancy. 4.8. Operational Definition and Definition of Terms 4 Knowledge: -Accumulated awareness or information that one has gained on nutrition during pregnancy through learning and practices. Good: if 75%or¾knowledge questions were correctly answered. Fair: if 50%-75%knowledg equestions were correctly answered. Poor: only 25% of knowledge questions were correctly answered. Maternal nutrition: - Refers to nutritional needs of women during the antenatal and postnatal period. Pregnancy: - is a state of bearing developing fetus/embryo within the uterus from Period of fertilization to delivery. Dietary practice: the observable actions of an individual that could affect his/her or others’ nutrition, such as eating, feeding, cooking and selecting foods.. 4. 9. Data Processing and Analysis The data was collected first and then checked for completeness and internal consistency then it was sorted, grouped and stored on the tally sheet by using computer. Processed data was analyzed using descriptive statistics of frequency and percentage. Tables were prepared and calculation were done by using computer. The association between explanatory variables and dietary practices were determined by inferential statistics of chi square test using SPSS software. And p-values of <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. 11 4.10. Ethical Consideration Ethical clearance and permission from Jimma University CBE office was obtained and the permission as well as the purpose and objective of the research was fully explained to each study participants to obtain their verbal consent prior to the interview and collection of data. Privacy and confidentiality of data was kept. 4.11. Dissemination Plan The findings of the study will submitted to CBE office of Jimma University, and also will be submitted to school of midwifery as part of bachelor of science in midwifery thesis and other concerned bodies. 12 CHAPTER FOUR RESULT From all 239 pregnant women attending ANC clinics in health centers of Jimma town with convenient non-probability sampling procedure was used to select the study participants and with 100% response rate, all were responded. Socio- demographic characteristics of the participants Out of 239 study participant most of participant 96(40.2) age lies between age of 25-29. And most of participants 191(79.9) live in urban. Majority of study participants 156(65.3%) are oromo in ethnicity, 138(57.7%)of participants are muslim in religion, and 90(37.7%) of participants can read and write,233(97.5%) of participants are married, 158(66.1%) of participants are house wife. Majority of participants 182(76.2%) have 1-4 family size. Most of participants 162(67.8%) have medium monthly income. Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in Jimma town public health centers, Jimma, south west Ethiopia (239) No. Charac Type Frequency % 15-19 7 - 20-24 51 21.3 25-29 96 40.2 30-34 69 28.9 35-39 16 6.7 Urban 191 79.9 Rural 48 20.1 Oromo 156 65.3 Amhara 41 17.2 teristic s 2. Residence Age 1. group Ethnic 3. 13 Tigray 6 - Gurage 22 9.2 Keffa 14 5.9 Muslim 138 57.7 Christian 100 41.8 Other 1 - Illiterate 64 26.8 Read and write 90 37.7 Primary school completed 14 5.9 Secondary school completed 24 10.0 College/university graduate 46 19.2 Secondary degree and 1 - Single 2 - Married 233 97.5 Divorced 4 1.7 Widowed 0 - Illiterate 42 17.6 Read and write 44 18.4 Primary school completed 27 11.3 Secondary school completed 25 10.5 College/university graduate 94 39.3 Secondary degree and above 7 - Employed (gov’t/non gov’t) 41 17.2 Religion 4. Level of education 5. above s statu onal 8. upati 7. Occ If married, partners educational status Marital status 6. 14 Family size 9. Monthly income 10. Self employed 40 16.7 House wife 158 66.1 1 to 4 182 76.2 4 to 6 50 20.9 above six 7 - Poor 27 11.3 Medium 162 67.8 Fair 48 20.1 Good 1 - 1. Obstetric characteristics of the participants In this study, the total number of observed population was 239 peoples. The data of these amount populations were evaluated for the obstetric characteristics of mothers under investigation. The result obtained from the data gathered during the interview was calculated and described by the following table. Table 2: Obstetric characteristics of the participants in Jimma town public health centers, Jimma, south west Ethiopia (239) No. 1 2. Characteristics Number Of Pregnant Gestational Above 28 Weeks Frequency % 1-3 Pregnancy 182 76.5 3-6 Pregnancy 55 23.1 >6 Pregnancy 2 - Total 239 100% 1-3 Pregnancy 174 87.9 3-6 Pregnancy 23 11.6 15 >6 Pregnancy Total 3 5. History Of Abortion Antenatal Visits For The Current Pregnancy Gestational Age In Weeks on ANC visit - 198 100% No 210 87.8% Yes 29 12.1% Total 239 100% Less Than 4 Visit 212 88.7 27 11.3 Total 239 100% Less Than 28 209 87.4 30 12.6 239 100% Greater Than 4 Visit 6. 1 Greater Than 28 Total 2. Knowledge of participant on dietary practice Most of study participant 187(78.2%) eat only what they craves, majority of participants 132(55.2%) have knowledge on increasing amount of food during pregnancy and they take more food. Most of study participant 146(61.1%) have no knowledge on iron source food. Most of participants 176(73.6%) do not have knowledge on carbohydrate source of food but most of participant 150(62.8%) have knowledge on protein source food. Majority of study participants 209(87.4%) have knowledge on using iodized salt during pregnancy. Majority of participants124 (51.9%) knows that maternal undernutrition can cause fetal low birth weight and causes still birth. Majority of study participants 217(90.8%) have knowledge on balanced diet during pregnancy. Table 3 Knowledge of the participants on dietary practice in Jimma town public health centers, Jimma, south west Ethiopia (239) Variables Knowledge on eating variety food Category variety of food Only what she craves Don't know Total More food Less food Knowledge on increasing amount of food during pregnancy 16 Frequency 43 187 9 239 132 35 Percent 18 78.2 100% 55.2 14.6 The same as Total Red meat, liver and fish Fruits and vegetables Don't know Total 1. No 2. Yes 3. Total 72 239 73 20 146 239 176 63 239 30.1 100% 30.5 8.4 61.1 100% 73.6 26.4 100% Knowledge about protein source foods 1. No 2. Yes Total 89 150 239 37.2 62.8 100% Knowledge on using iodized salt during pregnancy 1. No 2. Yes Total 30 209 239 12.6 87.4 100 Knowledge on duration of Iron supplementation 1. Do not know 2. 3 months 3. 6 months Total 9 3 227 239 95.0 100% 1. Do not know 110 46 2. No effect on fetal weight 5 - 3. Low birth weight and stillbirth 124 51.9 239 98 141 239 33 206 239 22 217 239 100% 41 59 100 13.8 86.2 100 9.2 90.8 100 Knowledge on food source for iron Knowledge about carbohydrate source foods Knowledge on effect of maternal under nutrition on fetal weight Knowledge on fetal complication of maternal under nutrition Knowledge on maternal complications of under nutrition Knowledge on balanced diet 17 Total 1. 2. Total 1. 2. Total 1. 2. Total No Yes No Yes No Yes 3. Dietary practice of pregnant mothers Majority of study participant has medium level of dietary practice during pregnancy,while very few has good practice. Table 4 Dietary practice of the participants in Jimma town public health centers, Jimma, south west Ethiopia (239) Dietary Practice Level of practice Poor Medium Fair Good Total Frequency 27 162 48 1 238 Percent 11.3 68.1 20.2 100% 4. Factor Associated to Dietary Practice of Pregnant Mothers In this study, the total number of observed population was 239 peoples. According to the finding Majority of factor studied has no association with dietary practice .Factor likes level of education, occupation, monthly income, knowledges on eating variety of foods, foods source of iron, carbohydrates source foods, effect of maternal undernutrition on fetal weight, fetal complication of maternal underweight has association with dietary practice of pregnant mothers Table 4: Result of Cross tabulation and Chi-square of factor associated with Dietary practice of the participants in Jimma town public health centers, Jimma, south west Ethiopia (239) Variables Categor y Count Dietary practice Number of Pregnant 1-3 Pregnan cy Frequency Percent From total Fair Goo d Tot al Medium 23 120 38 1 182 9.7 50.6 16 0.4 3-6 Pregnan cy Frequency Percent 4 1.7 40 16.9 10 4.2 0 0.0 >6 Pregnan cy Frequency 0 1 0 0 76. 8 54 22. 8 1 Percent 0 0.4 0 0 0.4 1 0.4% 237 100.0 % 1 174 Frequency Percent of total Gestational Poo r 1-3 Frequency 27 11.4 % 24 18 161 67.9% 114 48 20.3% 35 Chi squ are P valu e 2.2 93 0.7 02 8.1 0.2 Above 28 Weeks Pregnan cy 3-6 Pregnan cy >6 Pregnan cy Percent Frequency Percent Frequency Percent Frequency Percent of total Antenatal Visits For The Current Pregnancy Family size 17.8% 0.5% 88.3 % 1 19 2 0 22 0.5% 9.6% 1.0% 0.0% 11.2 % 0 0 1 0 1 0.0% 0.0% 0.5% 0.0% 0.5% 25 133 38 1 197 12.7 % 24 67.5% 19.3% 0.5% 145 41 1 100.0 % 211 60.9% 17.2% 0.4% 17 7 0 Frequency Greater Than 4 Visit Frequency 10.1 % 3 Percent 1.3% 7.1% 2.9% 0.0% 11.3 % Frequency 27 162 48 1 238 Percent of total Frequency Percent 11.3 % 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% 100.0 % 141 59.2% 42 17.6% 1 0.4% Frequency 24 10.1 % 3 21 6 0 208 87.4 % 30 Percent 1.3% 8.8% 2.5% 0.0% 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency 27 11.3 % 21 120 40 1 Percent 8.8% 50.4% 16.8% 0.4% 4 37 8 0 Percent 1.7% 15.5% 3.4% 0.0% Frequency Percent Total Total percent 5 2.1% 162 68.1% 0 0.0% 48 20.2% 0 0.0% 1 0.4% 125 52.5% 43 18.1% 1 0.4% 37 5 0 Greater Than 28 Percent Frequency Total 1-4 family size 4-6 family size Frequency 1.Urban Frequency Percent 2 0.8% 27 11.3 % 22 9.2% 2 urban Frequency 5 Above six pregnancy U Residenc y 57.9% Less Than 4 Visit Less Than 28 Antenatal Visits For The Current Pregnancy 238 12.2 % 19 88.7 % 27 12.6 % 238 100. 0% 182 76.5 % 49 20.6 % 7 2.9% 238 100. 0% 191 80.3 % 47 36 01 0.7 47 0.7 82 0.2 18 1 5.1 80 0.5 21 3.8 86 0.2 72 4 Percent 2.1% 15.5% 2.1% 0.0% 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency 27 11.3 % 14 98 25 0 Percent 5.9% 41.2% 10.5% 0.0% Christian Frequency Percent 12 5.0% 64 26.9% 23 9.7% 1 0.4% Other Frequency 1 0 0 0 57.6 % 100 42.0 % 1 Percent 0.4% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.4% Frequency Percent 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency Percent Frequency 27 11.3 % 9 27 8 48 162 73 7 48 8 0 1 0 238 100.0 % 64 238 89 Percent 3.4% 30.7% 3.4% 0.0% 3 6 5 0 Percent Frequency Percent 1.3% 0 0.0% 2.5% 20 8.4% 2.1% 4 1.7% 0.0% 0 0.0% Frequency Percent 6 2.5% 15 6.3% 24 10.1% 1 0.4% 1 0 0 0 0.0% 162 68.1% 0.0% 48 20.2% 0.0% 1 0.4% Frequency 0.4% 27 11.3 % 6 16 18 1 Percent 2.5% 6.7% 7.6% 0.4% Frequency 3 28 9 0 Percent 1.3% 11.8% 3.8% 0.0% Frequency Percent 18 7.6% 118 49.6% 21 8.8% 0 0.0% 17 7.1% 128 53.8% 17 7.1% 0 0.0% Total Percent Religion Muslim Total Percent Level of education 1Illiterate 2Read and write 3Primary school Frequency 4 secondary College 6 secondary degree Frequency Percent Total Percent Occupation employed self employed housewife Income Less than 3000 Frequency Percent 20 19.7 % 238 100.0 % 137 10. 514 0.1 05 63. 962 0.0 0* 27. 133 0.0 0 46. 691 0.0 00* 37.4 % 14 5.9% 24 10.1 % 46 19.3 % 1 0.4% 238 100. 0% 41 17.2 % 40 16.8 % 157 66.0 % 162 68.1 % 5 18 7 0 30 Percent 2.1% 7.6% 2.9% 0.0% Greater than 6000 Fluency Percent 5 2.1% 16 6.7% 24 10.1% 1 0.4% Single Frequency 1 1 0 0 12.6 % 46 19.3 % 2 Percent Frequency 0.4% 24 0.4% 159 0.0% 48 0.0% 1 0.8% 232 Percent 10.1 % 2 0.8% 66.8% 20.2% 0.4% 2 0.8% 0 0.0% 0 0.0% 97.5 % 4 1.7% 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency Percent Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 0 0.0% 5 2.1% 7 2.9% 37 15.5% 0 0.0% 8 3.4% 0 0.0% 0 0.0% 25-29 Frequency Percent 15 6.3% 59 24.8% 21 8.8% 1 0.4% 30-34 Requency Percent 7 2.9% 44 18.5% 18 7.6% 0 0.0% 35-39 Frequency Percent Frequency 0 0.0% 27 15 6.3% 162 1 0.4% 48 0 0.0% 1 Percent 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% Frequency Percent 11.3 % 5 2.1% 15 6.3% 22 9.2% 1 0.4% Only what she craves Frequency 21 140 25 0 Percent 8.8% 58.8% 10.5% 0.0% Don’t know Frequency Percent 1 0.4% 7 2.9% 1 0.4% 0 0.0% Total Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 14 5.9% 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% 81 34.0% 36 15.1% 1 0.4% 3001-5999 Marital status Married Divorced Frequency Frequency Percent Frequency Total Age 15-19 20-24 Total Knowledge on eating variety food Knowledge on increasing Variety of food More food Frequency Percent 21 238 100. 0% 7 2.9% 50 21.0 % 96 40.3 % 69 29.0 % 16 6.7% 238 100. 0% 43 18.1 % 186 9.6 70 0.1 39 14. 184 0.2 89 38. 059 0.0 0* 10. 647 0.1 00 78.2 % 9 3.8% 238 100. 0% 132 55.5 % amount of food during pregnancy 4 28 3 0 35 Percent 1.7% 11.8% 1.3% 0.0% Frequency Percent 9 3.8% 53 22.3% 9 3.8% 0 0.0% Frequency 27 162 48 1 14.7 % 71 29.8 % 238 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% Frequency 11.3 % 20 133 22 0 Percent 8.4% 55.9% 9.2% 0.0% Yes Frequency Percent 7 2.9% 29 12.2% 26 10.9% 1 0.4% Total Frequency Percent 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% No Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 12 5.0% 62 26.1% 14 5.9% 0 0.0% Yes Frequency Percent 15 6.3% 100 42.0% 34 14.3% 1 0.4% Total Frequency 27 162 48 1 11.3 % 1 0.4% 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% 24 10.1% 5 2.1% 0 0.0% Less food The same as Total Frequency Percent Knowledge about carbohydrate source foods No Knowledge about protein source Percent Knowledge on using iodized salt during pregnancy Knowledge food source of Iron No Frequency Percent 100. 0% 30 12.6 % 208 87.4 % 238 100. 0% 73 138 58.0% 43 18.1% 1 0.4% 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency 39 26 0 Percent 3.4% 16.4% 10.9% 0.0% 30.7 % Frequency Percent Frequency Percent 1 0.4% 18 7.6% 10 4.2% 113 47.5% 8 3.4% 14 5.9% 1 0.4% 0 0.0% Frequency 27 162 48 1 20 8.4% 145 60.9 % 238 Frequency Percent Total Frequency Percent Red meat, liver and fish Fruits and vegetables Total 73.5 % 63 26.5 % 238 100. 0% 88 37.0 % 150 63.0 % 238 26 10.9 % 27 11.3 % 8 Yes Don’t know 100. 0% 175 22 27. 811 0.0 0* 2.6 06 0.4 56 3.013 37. 581 0.3 90 0.0 00* Do not know Frequency 11.3 % 0 Percent 0.0% 3.4% 0.4% 0.0% 3.8% 3 months Frequency Percent 1 0.4% 2 0.8% 0 0.0% 0 0.0% 3 1.3% 6 months Frequency Percent 152 63.9% 47 19.7% 1 0.4% Total Frequency Percent 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Frequency Percent 26 10.9 % 27 11.3 % 16 6.7% 81 34% 12 5% 0 0 226 95.0 % 238 100. 0% 109 45.8 Frequency Percent 0 0.0% 5 2.1% 0 0.0% 0 0.0% 5 2.1% Frequency Percent 11 4.6% 76 31.9% 36 15.1% 1 0.4% 124 52.1 % Frequency 27 162 48 1 238 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% 72 30.3% 11 4.6% 0 0.0% 100. 0% 97 40.8 % 141 59.2 % 238 100. 0% 32 13.4 % 206 Percent Duration of Iron supplementati on Knowledge on effect of maternal under nutrition on fetal weight Do not know No effect on fetal weight Low birth weight and still birth Total Knowledge on maternal complications of under nutrition Knowledge on balanced diet 20.2% 0.4% 8 1 0 100. 0% 9 No Frequency Percent 11.3 % 14 5.9% Yes Frequency Percent 13 5.5% 90 37.8% 37 15.5% 1 0.4% Total Frequency Percent 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% No Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 6 2.5% 19 8.0% 7 2.9% 0 0.0% Yes Frequency 21 143 41 1 Percent 8.8% 60.1% 17.2% 0.4% Total Frequency Percent 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% No Frequency Percent Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 4 1.7% 23 9.7% 14 5.9% 148 62.2% 3 1.3% 45 18.9% 0 0.0% 1 0.4% Percent Knowledge on fetal complication of maternal under nutrition 68.1% Yes 23 86.6 % 238 100. 0% 21 8.8% 217 91.2 3.9 69 6.8 1 15. 807 0.0 15* 9.3 04 0.0 26* 2.4 06 0.4 92 1.7 03 6.3 6 Total Frequency 162 48 1 68.1% 20.2% 0.4% 23 9.7% 18 7.6% 0 0.0% yes Frequency Percent 11.3 % 9 3.8% No Frequency Percent 18 7.6% 139 58.4% 30 12.6% 1 0.4% Frequency Percent 27 11.3 % 162 68.1% 48 20.2% 1 0.4% Percent History of abortion 27 Those “*” at end of their P values are Significant at P value less than 0.05. 24 % 238 100. 0% 50 21.0 % 188 79.0 % 238 100. 0% 0.0 2* 15. 133 CHAPTER : FIVE 5.1. Discussion Studies in Africa have indicated that at similar level of income, households in which women have a greater control over their income are more likely to be food seller. Marital status of the women is associated with house hold headship and other social and economic status of the women that affect their nutritional status (15).In this Study 53.8% of participants has less than 3000ETB and medium to poor dietary practice. In this study 78.2 %( 186) eat only what they craves and only 18.1% has knowledge on eating variety of foods. Research agrees with this findings; In Nigeria it shows They have limited intake animal source food, fruit and vegetables. Studies show that nutritional knowledge affects the quality of food intake and healthy choices of purchased food (18).In addition A study in Tanzania, 19% of women in the age of 15-19 groups suffer from acute malnutrition, due to inadequate intake of variety amount of dietary sources and 43% of household uses salt that is inadequately iodized (17).In this study 87.4% has knowledge on using iodized salt. This may be because of study area is on urban population majorly. In our study about 73.5%of participant does not know food source of carbohydrates. It agrees with DHS survey, conducted in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, Niger, Senegal and Zambia show a greater proportion of mothers age 15-19 and 40-49 that exhibit chronic energy deficiency (CED)(18). In this study level of education, income, occupation, and knowledge on different dietary sources has association with dietary habit. In line with this study . In Ghana, a study among 502 pregnant women. Socio demographics such as, educational, social class and geographical location have also been found to correlate significantly with dietary habit and hence, nutrient intake especially among pregnant women reported that pregnant women with higher family income and high level of formal education tended to consume on notorious diet with greater frequency than poor groups (22). In This study employment has significant association with dietary habit (P=0.00). In line with this study other study shows, Women’s employment increase household with consequent benefit to house hold nutrition in general and the women’s nutritional status in particular (19). In this study residency place has no association with dietary habit, but contrary According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, conducted in 2008, the micronutrient consumption pattern of mothers in urban areas was better than the intake of rural women (15).This may because of country variation. 25 5.2. Conclusions Majority of women have poor dietary practice. Education, income, knowledge about different food is significant association with dietary practice. Majority of study participants did not take additional meal during pregnancy. Skipped one of their regular meals. About 51.2% have fair knowledge on variety food eating. Majority of them has no good nutritional practice. About 67.8 of women have medium regarding dietary practice. 5.3. Recommendations For Stakeholders: Since their dietary practice is medium to low JMC,Jimma Zone health offices and other stakeholders have to give awareness creation for mass community about nutrition of pregnant women For health Professionals: Health professional working in the study area and similar setting have take training regarding counseling pregnant women on preparing locally available food appropriately to combat the problem of malpractice among community Health extension workers: We recommend health extension workers in the area to teach pregnant women appropriately about feeding during pregnancy 26 REFERENCES 1. Aliwo S, Fentie M, Awoke T, Gizaw ZJBrn. Dietary diversity practice and associated factors among pregnant women in North East Ethiopia. 2019;12(1):1-6. 2. Maqbool M, Dar MA, Gani I, Mir SA, Khan M, Bhat AUJWJoP, et al. Maternal health and nutrition in pregnancy: an insight. 2019;8(3):450-9. 3. Ademuyiwa M, Sanni SJIJBVAFE. Consumption pattern and dietary practices of pregnant women in Odeda local government area of Ogun state. 2013;7:11-5. 4. Ahmed T, Hossain M, Sanin KIJAoN, Metabolism. Global burden of maternal and child undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. 2012;61(Suppl. 1):8-17. 5. Lindsay K, Gibney E, McAuliffe FJJohn, dietetics. Maternal nutrition among women from Sub‐Saharan Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, and potential implications for pregnancy outcomes among immigrant populations in developed countries. 2012;25(6):534-46. 6. Nnam N. Conference on ‘Food and nutrition security in Africa: new challenges and opportunities for sustainability’Improving maternal nutrition for better pregnancy outcomes. 2015. 7. Darnton-Hill I, Mkparu UCJN. Micronutrients in pregnancy in low-and middleincome countries. 2015;7(3):1744-68. 8. Lee SE, Talegawkar SA, Merialdi M, Caulfield LEJPhn. Dietary intakes of women during pregnancy in low-and middle-income countries. 2013;16(8):1340-53. 9. Ali F, Thaver I, Khan SAJJoAMCA. Assessment of dietary diversity and nutritional status of pregnant women in Islamabad, Pakistan. 2014;26(4):506-9. 10. Echevarría-Zuno S, Mejía-Aranguré JM, Mar-Obeso AJ, Grajales-Muñiz C, RoblesPérez E, González-León M, et al. Infection and death from influenza A H1N1 virus in Mexico: a retrospective analysis. 2009;374(9707):2072-9. 11. Patricia O, Ekebisi CJFSNT. Assessing dietary diversity score and nutritional status of rural adult women in Abia State, Nigeria. 2016;1(1):000106. 12. Mugyia ASN, Tanya ANK, Njotang PN, Ndombo PKJHs, disease. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant mothers towards maternal dietary practices during pregnancy at the Etoug-Ebe Baptist Hospital Yaounde. 2016;17(2). 13. Bailey RL, West Jr KP, Black REJAoN, Metabolism. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. 2015;66(Suppl. 2):22-33. 27 14. Zerfu TA, Umeta M, Baye KJJoH, Population, Nutrition. Dietary habits, food taboos, and perceptions towards weight gain during pregnancy in Arsi, rural central Ethiopia: a qualitative cross-sectional study. 2016;35(1):1-7. 15. Agency CS, ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. 2016. 16. FAO FJRF. Minimum dietary diversity for women: a guide for measurement. 2016;82. 17. Parmar A, Khanpara H, Kartha GJa. A study on taboos and misconceptions associated with pregnancy among rural women of Surendranagar district. 2013;4(1). 18. Amugsi DA, Lartey A, Kimani-Murage E, Mberu BUJJoH, Population, Nutrition. Women’s participation in household decision-making and higher dietary diversity: findings from nationally representative data from Ghana. 2016;35(1):1-8. 19. Kominiarek MA, Rajan PJMC. Nutrition recommendations in pregnancy and lactation. 2016;100(6):1199-215. 20. Forsum E, Löf MJARN. Energy metabolism during human pregnancy. 2007;27:27792. 21. Oh C, Keats EC, Bhutta ZAJN. Vitamin and mineral supplementation during pregnancy on maternal, birth, child health and development outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2020;12(2):491. 22. Sfakianaki AKJF. Prenatal vitamins: A review of the literature on benefits and risks of various nutrient supplements. 2013;48(2):77. 23. Organization. WH. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2015: estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division: World Health Organization; 2015. 24. Ban K-m. Sustainable Development Goals. 2016. 25. Csa IJCSA. Central Statistical Agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, Addis Ababa. 2016. 26. De‐Regil LM, Peña‐Rosas JP, Fernández‐Gaxiola AC, Rayco‐Solon PJCdosr. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. 2015(12). 27. Haider BA, Bhutta ZAJCDoSR. Multiple‐micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. 2017(4). 28. C. UWa. Mathers, Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030), vol. 2016, no. 9, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, . 2017. 28 29. Zepro NBJSJPH. Food taboos and misconceptions among pregnant women of Shashemene District, Ethiopia, 2012. 2015;3(3):410-6. 30. Lartey AJPotNS. Maternal and child nutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and interventions. 2008;67(1):105-8. 31. Smith ER, Shankar AH, Wu LS, Aboud S, Adu-Afarwuah S, Ali H, et al. Modifiers of the effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on stillbirth, birth outcomes, and infant mortality: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 17 randomised trials in low-income and middle-income countries. 2017;5(11):e1090e100. 32. Baumgartner JJTLGH. Antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation: benefits beyond iron-folic acid alone. 2017;5(11):e1050-e1. 33. Nana A, Zema TJBp, childbirth. Dietary practices and associated factors during pregnancy in northwestern Ethiopia. 2018;18(1):1-8. 34. WHO. Global nutrition targets 2025: policy brief series (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.2). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2014. 35. Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995– 2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. 2013;1(1):e16-e25. 36. Ferreira GA, Gama FNJREI. Percepção de gestantes quanto o ácido fólico e sulfato ferroso durante o pré natal. 2010;3(2):578-89. 37. Abay A, Yalew HW, Tariku A, Gebeye EJAoPH. Determinants of prenatal anemia in Ethiopia. 2017;75(1):1-10. 38. Mariyam A, Dibaba BJJNDT. Epidemiology of malnutrition among pregnant women and associated factors in central refit valley of Ethiopia, 2016. 2018;8(01):1-8. 39. Haidar J, Melaku U, Pobocik RSJSAJoCN. Folate deficiency in women of reproductive age in nine administrative regions of Ethiopia: an emerging public health problem. 2010;23(3):132-7. 40. Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, Kanda M, Narita S, Bilano V, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis, 2. 2016;103(2):495-504. 41. Gernand AD, Schulze KJ, Stewart CP, West KP, Christian PJNRE. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. 2016;12(5):27489. 29 42. Abu-Saad K, Fraser DJEr. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. 2010;32(1):5-25. 43. Saldanha LS, Buback L, White JM, Mulugeta A, Mariam SG, Roba AC, et al. Policies and program implementation experience to improve maternal nutrition in Ethiopia. 2012;33(2_suppl1):S27-S50.Iqbal S, Ali IJJoA, Research F. Maternal food insecurity in low-income countries: Revisiting its causes and consequences for maternal and neonatal health. 2021;3:100091. 44. Mason JB, Saldanha LS, Martorell RJF, bulletin n. The importance of maternal undernutrition for maternal, neonatal, and child health outcomes: An editorial. 2012;33(2_suppl1):S3-S5. 45. Csa IJEd, health survey AA, Ethiopia, Calverton M, USA. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. 46. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. 2008;371(9608):243-60. 47. Organization WH. Good maternal nutrition: the best start in life. 2016. 48. Nnam NJPotNS. Improving maternal nutrition for better pregnancy outcomes. 2015;74(4):454-9 49. Pontes ELB, Passoni CMS, Paganotto MJCDEDS. Importância do ácido fólico na gestação: requerimento e biodisponibilidade. 2008;1(1). 50. Nutrition UNSSCo. By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition and leave no one behind. UNSCN Geneva (Switzerland); 2017. 51. Organization WH. Global targets 2025 to improve maternal, infant and young children nutrition. World Health Organization; 2017. 52. Blumfield ML, Hure AJ, Macdonald-Wicks L, Smith R, Collins CEJNr. Systematic review and meta-analysis of energy and macronutrient intakes during pregnancy in developed countries. 2012;70(6):322-36. 53. Blumfield ML, Hure AJ, Macdonald‐Wicks L, Smith R, Collins CEJNr. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of micronutrient intakes during pregnancy in developed countries. 2013;71(2):118-32. 54. Marangoni F, Cetin I, Verduci E, Canzone G, Giovannini M, Scollo P, et al. Maternal diet and nutrient requirements in pregnancy and breastfeeding. An Italian consensus document. 2016;8(10):629. 55. Nguyen CL, Hoang DV, Nguyen PTH, Ha AVV, Chu TK, Pham NM, et al. Low dietary intakes of essential nutrients during pregnancy in Vietnam. 2018;10(8):1025. 30 56. Alemayehu MS, Tesema EMJIJNFS. Dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Gondar town north west, Ethiopia, 2014. 2015;4(6):707-12. 57. Daba G, Beyene F, Garoma W, Fekadu HJS, Technology, Journal AR. Assessment of nutritional practices of pregnant mothers on maternal nutrition and associated factors in Guto Gida Woreda, east Wollega zone, Ethiopia. 2013;2(3):105-13. 58. Darnton-Hill I, editor Global burden and significance of multiple micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy. Meeting micronutrient requirements for health and development; 2012: Karger Publishers. 59. Qureshi Z, Khan RJJoAMCA. Dietary intake trends among pregnant women in rural area of rawalpindi, Pakistan. 2015;27(3):684-8. 60. Demissie T, Muroki N, Kogi-Makau WJEJoHD. Food taboos among pregnant women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. 1998;12(1). 61. Kuche D, Singh P, Moges DJJPSI. Dietary practices and associated factors among pregnant women in Wondo Genet District, southern Ethiopia. 2015;4(5):270-5. 62. Kavle J, Mehanna S, Khan G, Hassan M, Saleh G, Galloway RJURWD. Cultural beliefs and perceptions of maternal diet and weight gain during pregnancy and postpartum family planning in Egypt. 2014. 63. Nigatu M, Gebrehiwot TT, Gemeda DHJAiPH. Household food insecurity, low dietary diversity, and early marriage were predictors for Undernutrition among pregnant women residing in Gambella, Ethiopia. 2018;2018. 31 ANNEX: QUESTIONNAIRE JIMMA UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF HEALTH FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES School of midwifery Annex one: Participant information sheet and consent form I: Participant information sheet Title: dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in jimma town public health facilities, Jimma, south west Ethiopia, 2022 . Principal investigator: Dureti Kebede (BSc midwife student) Introduction: Good morning/good afternoon: Hello! My name is_______________ .I am here today to collect data on dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma town public health facilities, Jimma, south west Ethiopia, conducted by Dureti Kebede who is BSc student in midwifery. Purpose: The purpose of this study is to assess dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma town public health facilities, Jimma, south west Ethiopia, Procedure and participation: You are kindly asked to take part in this study and to respond genuinely. Your cooperation and willingness is greatly helpful in identifying problems related to the issue. The data collector will read the questionnaire for you to respond to those items This questionnaire may take you a maximum of 15 to 20 minutes. Your Participation is voluntary and you are not obligated to answer any question you do not wish to answer. Confidentiality: Your personal identifiers that could be confidential to you like your name will not be written in this form and will never be used in connection with any information you provide. All information provided by you will be kept strictly confidential Benefit: your benefit from the study will come with the possible advantages from the recommendations that will be drawn based on the findings of the study. Risk: There will not be possible risk associated with participating in this study. 32 Results Dissemination: the findings of the study will be disseminated to different concerned bodies as well you can find it with soft and hard copy by contacting the principal investigator by the address given below. Freedom to withdraw: If you feel uncomfortable with the question, it is your right to drop it any time you want. Again, you can withdraw from the study at any time you wish to withdraw Person to contact: if you have any concern, please feel free to contact the principal investigator any time you wish to contact. If you want more information and check about this project, you can contact with: Principal investigator name and address: Dureti Kebede/ email: Tel. +251 II: Participant consent form Title of the research: ‘‘dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in jimma town public health facilities, Jimma, south west Ethiopia, 2022 ’’ I have been well aware of that this research is undertaken as a partial fulfilment of BSc degree in midwifery which is fully supported and coordinated by the School of midwifery, faculty of health sciences, and the designate principal investigator is Dureti Kebede. I have been fully informed in the language i understand about the research project objectives I have been informed that all the information I shall provide will be kept confidential. I understood that the research has no any risk and no composition. I also knew that I have the right to withhold information, skip questions to answer or to withdraw from the study any time I have acquainted nobody will impose me to explain the reason of withdrawal. I have assured the right to ask information that is not clear about the research before and or during the research work and to contact: Principal Investigator’s Name: Dureti Kebede Tel: +251 I have read this form, or it has been read to me in the language I comprehend and understood the condition stated above, therefore, I am willing and confirm my participation by signing the consent. Agreed to participate in the study (tick “√”) Yes No Questionnaire 33 Part I: Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants Instruction: please indicate the choice of the participants by encircling from the given options or writing on the space provided for each item S.no Item 001 Age 002 Residence 003 Ethnicity 004 Religion 005 Level of education 006 Marital status 007 If married, partners educational status 008 Occupational status 009 010 Family size Monthly family income Options __________________ 1. Urban 2. Rural 1. Oromo 2. Amhara 3. Tigray 4. Gurage 5. Keffa 6. Others. Specify___________ 1. Muslim 2. Christian 3. Others. Specify ___________________ 1. Illiterate 2. Read and write 3. Primary school completed 4. Secondary school completed 5. College/university graduate 6. Secondary degree and above 1. Single 2. Married 3. Divorced 4. Widowed 1. Illiterate 2. Read and write 3. Primary school completed 4. Secondary school completed 5. College/university graduate 6. Secondary degree and above 1. Employed (gov’t/non gov’t) 2. Self employed 3. Hose wife _________________ ________________ 34 Part II: Obstetric characteristics of the participants Instruction: please indicate the choice of the participants by encircling from the given options or writing on the space provided for each item S.no Item 011 How many pregnancies have you ever had? 012 How many births do you have? with gestational age of more than 28 weeks 013 Do you have history of abortion? 014 015 016 If yes to question number 013, how many times? How many antenatal visits do you have for the current pregnancy? Gestational age in weeks Options ___________ ____________ 1. No 2. Yes __________ ___________ ____________ Part III: Knowledge of the participants on dietary practice Instruction: please indicate the choice of the participants by encircling from the given options for each item S.no Item Options 017 Knowledge on eating variety food 1. Variety of food 2. Only what she craves 3. Don't know 018 Knowledge on increasing amount 1. More food of food during pregnancy 2. Less food 3. The same as 019 Knowledge on food source for 1. Red meat, liver and fish iron 2. Fruits and vegetables 3. Don't know 020 Knowledge about carbohydrate 4. No source foods 5. Yes 021 Knowledge about protein source 3. No foods 4. Yes 022 Knowledge on using iodized salt 3. No during pregnancy 4. Yes 023 Knowledge on duration of Iron 4. Do not know supplementation 5. 3 months 6. 6 months 024 Knowledge on effect of maternal 5. Do not know under nutrition on fetal weight 6. No effect on fetal weight 7. Low birth weight and stillbirth 025 026 Knowledge on fetal complication of maternal under nutrition Knowledge on maternal 3. No 4. Yes 3. No 35 complications of under nutrition Knowledge on balanced diet 4. Yes 027 4. No 5. Yes Part IV: Dietary practice of pregnant mothers Instruction: please indicate the choice of the participants by encircling from the given options for each item S.no Item 028 Addition of at least one additional meal from non- pregnant diet 029 Eating 2 to 3 servings of meat, fish, nuts or legumes per day 030 Eat 2 to 3 servings of dairy (milk, eggs, yogurt, and cheese) per day 031 Eat 2 servings of green vegetables; 1 serving of a yellow vegetable per day Eat 2 to 3 servings of fruit per day 032 033 034 Eat 3 servings of whole grain breads, cereals, or other high-complex carbohydrates Use Iodized salt 035 Taking Iron supplement tablets in the current pregnancy 036 Alcohol use and smoking in the current pregnancy 037 Decreasing coffee use in the current pregnancy 038 Avoiding one or more food type during pregnancy 039 Avoiding at least one meal from non-pregnant state 36 Options 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 1. No 2. Yes 37