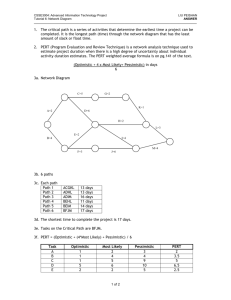

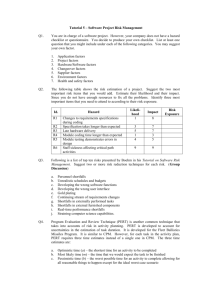

tips for project managers who have never managed Nathan Johnson, Ph.D., MPA I n today’s business environment of doing less with more, knowledge workers with little to no management experience may be given the task of managing a project. Typically these first assignments will be smaller, less complex projects. Regardless of size however, leading a project for the first time can be a daunting task, particularly if the last time the employee thought about being a project manager was in a college classroom. Although the “trial by fire” method of learning is not ideal in the workplace, it is a reality for many people with no project management experience. Are you that inexperienced employee who has been asked to manage a project? If so, read the following tips to help you formulate a successful strategy for navigating your project. Remember the Golden Triangle! As the project manager, your job is now to ensure the completion of all project objectives. To successfully do that, you must work to ensure three things: that the scope of the project remains feasible, the cost of the project stays within the boundaries set by the budget, and the project is completed on time. In the project management arena, these three items are known as the Golden Triangle of Project Management. Scope Projects typically start out with an end product in mind. That end result is bounded by project parameters known as the scope. As project manager, keeping your project within its defined scope will demand a lot of your time. Scope management entails carrying out the needed processes to make sure that your project team gets all the work required, and only the work required, completed to finish the project. True, there are always ways to make a project better, grander, or more impressive. But in the end, these types of additions lead to more work, more money, and more time...all of which can negatively impact the project’s completion. The addition of project parameters is known as scope creep, and it’s something the project manager has to guard against or face certain frustration, or worse, failure. As project manager, know the scope of the project and do your very best to stick to it. Keep changes to a minimum, and for those that are required of you, ensure that all affected parties understand the potential consequences to the budget and timeline of the overall project. Cost Developing and maintaining your project’s budget through the controlling of costs is another responsibility that will fall to the project manager. Developing the budget for your project can be a daunting task, but a key rule of thumb is never lie to yourself. As humans, we tend to make overly optimistic assessments about almost everything. Don’t fall into that trap with your budgets...set realistic expectations with cost planning. Allow adequate time to create your budget; developing lengthy or 9 complex budget estimates under pressure typically results in poor budget estimates. Never sugarcoat the truth to secure advantageous funding. If possible, bring in someone with budget estimation skills to help guide you in the process. An experienced eye will know when an estimate is too optimistic, put together too quickly, or making promises it can’t keep. Once your budget is set, control it. Avoiding scope creep will go a long way in helping you stay on budget. Consider creating multiple project milestones that will help you keep track of where you are in your project in both schedule and expenditures. Knowing how much money you’ve spent at key points in the project can help you better manage expenditures at the next steps of the project. Time Developing a schedule for the project is more than just determining start and end dates; knowing how long it will take to complete the component activities of the project is vital to a successful and timely completion. Determining which activity times you can let slip when it comes to the schedule (known as float), and knowing those processes that absolutely cannot fall behind (activities on the project’s critical path to completion) can give you actionable information when it comes to prioritizing people and money resources for your project. Developing a network diagram that shows the critical path and 10 activity float is beyond the scope of this article. But experienced project managers will know which activities are on the critical path and funnel the appropriate resources to those activities to make sure they are successfully completed. Estimating individual activity durations within the project can be a daunting task, particularly for those with little to no familiarity with the process. If there are no voices of experience or documentation from similar projects to reference, the Program Evaluation and Review Technique, or PERT, method can help. PERT uses three duration estimates, the optimistic time, the most likely time, and the pessimistic time, to quantify the expected activity duration. The PERT formula is as follows: (Optimistic + [4 x Most Likely] + Pessimistic) 6 For instance, if you were trying to estimate the duration for the activity Parking Lot Striping in a building construction project, you might estimate the optimistic time to be 10 hours, the most likely time at 16 hours, and the pessimistic time at 22 hours. Using the PERT formula, you would calculate the expected duration of the striping of the parking lot to be 16 hours. The advantage of the PERT estimate is that is removes a large degree of uncertainty that typically exists in project activity duration planning. Additionally, PERT estimates will typically develop slightly longer schedules than what the project will actually take. The result to the project manager is a bit of buffer for project completion and a welcome surprise when the project comes in ahead of schedule. A disadvantage is the extra time it takes to consider three separate durations for each project activity, particularly if your schedule contains multiple activities. Quality In addition to The Golden Triangle, many project managers are now recognizing the importance of quality throughout the life cycle of their projects (will it become The Golden Square?). Without taking quality into account in all aspects and stages of the project, you may find yourself with a discontented customer unwilling to accept the finished product. The customer may be your boss, but more often than not, will be a client your organization is working for. Having a dissatisfied customer at the end of the project will not only embarrass your organization, your boss, and your project team, it may also result in your removal from all future projects or termination. Maintain a mindset of quality throughout the planning, execution, and control of your project and push that mindset out to all the members of your team as well. Communication Management Throughout the life of the project, you’ll be communicating with various project team members, your boss, and any outside entities that have a role in the project such as external clients, vendors, community members, or regulatory agencies. These are all project stakeholders and good communication with them is essential. As the project manager you are responsible for the creation and collection of project information, its distribution to the appropriate parties, and its ultimate disposition. To be effective, you need to understand your stakeholders and their needs. Building good relationships with stakeholders, particularly with key players, is vital to a successful project outcome and allows you to answer questions such as: what is the stakeholder’s role in your project, how can they help you, what will the project do for them, what type of information do they need from the project team and what information does the project team need from them, how often do they need to be communicated with, and what is the best way to communicate with them (email, phone, face to face)? Since there is a lot to think about and manage, consider building a communication matrix in order to help your project team stay organized. The matrix will quickly and visually let you and your team see the identity, detail, direction, and frequency of communication for each of your project’s relevant stakeholders. In addition, the matrix can show who on your team is responsible for communicating with each stakeholder. Risk Management Dealing with risk is a ver y important part of project work, and is often overlooked by inexperienced managers. Risks are any possible events that can negatively affect the viability of a project or hinder achievement of project goals. Risk management entails identification, analysis, response planning, and monitoring on a project. Identification of risks can happen through a variety of information gathering activities such as brainstorming sessions with your team, asking other project managers about risks they have faced on similar projects, documentation from other projects, and interviewing key project stakeholders. Once identified, analysis of the risks can help you uncover how likely a risk is to occur, what its impact would be to the overall project, and when it is most likely to occur. Once risks are analyzed, they can be ranked by threat level and one of four responses can be determined: will you accept the risk because it’s not likely to happen or won’t be too impactful if it does; minimize the risk through preventive action; share the risk through relationships with outside entities; or will you transfer the risk to a third party via insurance or fixed price contracts? Consider budgeting for risks through a contingency reserve that allows you a cushion of cash in case the worst occurs. Once your risk response is planned, you need to watch for risk. What “triggers” or warning signs should you be looking for to signal your team that an identified risk is about to transpire? And remember, risk identification, planning, and response are not onetime tasks, but should continue throughout the life of your project. Ignore project risk at your own peril. Remember your People! As the new project manager, you are likely to have a project team reporting directly to you. Remember that these are your teammates and not your personal slaves. Lead confidently, set clear expectations of those working for you, and stick with them. But also be ready to listen to those who may have great ideas or more experience than you in a certain area (remember, you just started at this right?). At the end of a successful milestone or at project completion, give credit where credit is due. Encourage your team to maintain quality standards and keep their eye on the goal of successful project completion on time, and on schedule. A great piece of advice was once given to me by one of my bosses and it has stuck with me for years: be the boss that you’d want to work for he said. I always tried to maintain that attitude towards my people; by and large, they fell in behind me and supported me wherever and whenever they could. 11 Of course the above tips by no means represent an exhaustive guide to managing projects. Experienced project managers have many hours of project work under their belt and have worked both successful and unrealized projects. These are but a taste of the rich body of knowledge that exists to help guide you to better project implementation. If, at the end of your project, you find yourself enjoying the work of managing projects, consider looking into the Project Management Institute (PMI). PMI is the professional organization for project managers and provides its members a wealth of information, training, and certification in the field of project management. PMI’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (commonly referred to as the PMBoK Guide), is a literal handbook to project management offering in-depth information in all areas of the project as well as tools that can help project teams navigate projects of any size. The PMBoK Guide is available at bookstores and online retailers alike. S V Nathan Johnson is an assistant professor of management at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, NC. He teaches project management at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Before teaching, he ran projects at the local, state, and federal government level, most recently in the US Air Force as an active duty medical officer. 12 Copyright of Supervision is the property of National Research Bureau and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.