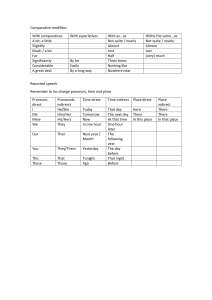

Text & Talk 2022; 42(5): 647–670 Jihua Dong* and Louisa Buckingham Identity construction and its collocation networks: a cross-register analysis of the finance domain https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2020-0094 Received June 11, 2020; accepted February 8, 2022; published online March 11, 2022 Abstract: This study investigates the use of explicit manifestations of authorial identity (namely self-mention pronouns) and their collocation networks in academic and workplace written texts. Based on a purpose-built corpus of research articles and the Hong Kong Financial Services Corpus (HKFSC), this study used Antconc and Graphcoll to extract and analyze the pronouns and their collocation networks. The statistical analysis shows that the academic register contains significantly more self-mention pronouns than the workplace corpus, which can be attributed to a stronger tendency towards self-positioning. We also identified significant register-specific semantic features of the collocation networks of selfmention pronouns. These findings contribute to our understanding of how selfmention pronouns operate in tandem with their surrounding context in registerspecific discourse. Pedagogically, the findings can be useful for workshop-based training for finance students and early-career professionals in this domain to support the development of the discipline-specific writing skills needed for careers in academia and industry. Keywords: academic discourse; collocation networks; self-mention pronouns; semantic domains; workplace discourse 1 Introduction The topic of authorial identity has attracted considerable attention from researchers (e.g., Matsuda and Tardy 2007; Mur Dueñas 2007; Sheldon 2009; Tang and John 1999). Authorial identity constitutes “a key aspect of persuasion” (Mur Dueñas 2007: 144) and contributes to “creating a self-promotional tenor” *Corresponding author: Jihua Dong, The School of Foreign Languages and Literature, Shandong University, 5 Hongjialou, Jinan, Shandong, 250000, China, E-mail: dongjihua@sdu.edu.cn Louisa Buckingham, The School of Cultures, Languages and Linguistics, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, E-mail: l.buckingham@auckland.ac.nz 648 Dong and Buckingham (Harwood 2005a: 1207). By explicitly manifesting their presence and navigating readers through the text, writers establish a particular persona in alignment with community conventions. This persona constitutes an essential element of writers’ authorial positioning in discourse construction (Ivanic 1998), that is, the way writers construct themselves in relation to their subject and the anticipated audience (Matsuda and Tardy 2007; McGrath 2016; Mur Dueñas 2007). Among the various possible materializations of writers’ identity, authors’ self-mention pronouns constitute the “most visible manifestation of a writer’s presence” (Tang and John 1999: 23). By utilizing self-mention pronouns, writers are able to display “their professional credentials and their familiarity with disciplinary (or community) practice” (Sheldon 2009: 251) and establish a relationship with envisaged readers and with their discourse community (Hyland 2001; Kuo 1999). In this study, we explore how authorial self-positioning is constructed in the finance industry workplace and the academic field of finance. As a discipline, finance encompasses both theoretical, or ‘pure’, and applied strands; research typically follows a quantitative paradigm (Becher and Trowler 2001) and draws on data related to “material and financial goods” (Bazerman 2010: 14). In this study, we first investigate the overall occurrences of self-mention pronouns in the two registers, and we then explore the collocation networks of the identified self-mention pronouns. Our study addresses the following two questions: (1) What are the register-specific uses of self-mention pronouns in the two different registers? (2) How do the two registers vary in terms of the collocation networks of the self-mention pronouns? The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a general review of the relevant studies in workplace written texts (Section 2.1), self-mention pronouns (Section 2.2), as well as previous studies conducted on collocation networks (Section 2.3). Then Section 3 describes the corpora and the methods used to retrieve the self-mention pronouns and their collocation networks, including the specific approach to statistical comparison. In Section 4, we present and discuss the results in terms of the frequency of self-mention pronouns and their functional uses (Section 4.1), as well as their specific collocation networks (Section 4.2). In Section 5, we summarize the main findings and the contributions of the present study, discuss the limitations, and provide suggestions and directions for future research. Identity construction and its networks 649 2 Literature review This section provides a general review of the previous studies conducted on workplace written texts, self-mention pronouns and collocation networks. 2.1 Workplace written texts Workplace communication, in particular written texts, has gained growing attention from researchers in English for specific/academic purposes interested in exploring transitions and strengthening linkages between the academy and the workplace. Both ethnographic and corpus-based studies have contributed to an understanding of different types of workplace communication, and their findings have facilitated the development of courses tailored to meet the needs of specific work contexts. Moore and Morton (2017) acknowledge the important connections between workplace written texts and university curricula, and have pointed to discrepancies between the features of written discourse in the workplace and in academia. For instance, workplace writing is shaped by an “action orientation” (Moore and Morton 2017: 603) and is characterized by a distinctive “need for brevity and concision” (598). The analysis of profession-specific corporate identity, therefore, can reveal the particular “social and environmental activities” (Breeze 2013: 166) and “identity values” (Mattioda and Vittoz 2014: 241) underlying the discursive practices of a community. The construction of identity has been a focus of previous research on workplace discourse. Studies of this type have explored various aspects of identity, including gender identity (Baxter 2010; Mullany 2007), and team identity (Djordjilovic 2012). In their explorations of the complexities of identity, these studies noted that identities are in a continual process of construction through linguistic resources (Hymes 1984: 44). Despite wide recognition of the role of linguistic markers in conveying identity, only very few studies have attempted to explore the linguistic features that contribute to identity construction in written registers of the workplace. For instance, Blitvich (2010) undertook an analysis of the rhetorical construction of corporate identity portrayed in the corporate value statements of 15 American corporations, with a particular focus on self-reference markers. The author discusses the manner in which the corporations’ identity construction is oriented towards their anticipated audiences and, as such, serves the dual purposes of public self-promotion and workplace internal socialization. Self-mention pronouns contribute to identity construction and, through these, differentiations between individual and group identity become salient. In the case of written texts, self-mention pronouns enable distinctions to be made between 650 Dong and Buckingham individual, shared and collective authorship. Within particular industry domains (such as finance), corporate identity is important and the contribution of individual company representatives to shaping company discourse cannot usually be identified (Balmer 2008). This is different in domains such as technology, for instance, where personal communication from individuals (e.g., Steve Jobs or Elon Musk) can be an important feature of company brand marketing. With the objective of uncovering community practice norms, we undertake a contrastive analysis of this feature of authorial positioning in the workplace and academic registers of the finance domain. 2.2 Self-mention pronouns The use of self-mention pronouns represents how writers “construct a credible representation of themselves and their work, aligning themselves with the socially shaped identities of their communities” (Hyland 2002: 1091), and represents a useful rhetorical strategy to “promot[e] a competent scholarly identity and gain accreditation for research claims” (Hyland 2001: 223). These pronouns are a feature of authorial self-positioning which has attracted considerable attention from researchers (i.e., Harwood 2005a, 2005b, 2006; Kuo 1999; Matsuda and Tardy 2007; McGrath 2016; Mur Dueñas 2007; Sheldon 2009; Tang and John 1999). Cross-disciplinary analyses of the self-mention pronouns in academic discourse have revealed discipline-specific features. For instance, Hyland (2001) explored the use of self-mention pronouns in eight disciplines, and found that social science texts contain a higher frequency of first-person pronouns than texts in the hard sciences (biology, physics, electrical engineering, and mechanical engineering). Harwood (2005b) identified discipline-specific features of the use of I and inclusive and exclusive we in research articles (RAs) in business and management, computing science, economics and physics. Moving beyond a purely text-based analysis, Harwood (2006) investigated the perspectives of experienced writers with regard to the appropriate or inappropriate use of self-mention pronouns (I and we) in political science writing. Harwood (2007) then took one step further by exploring academic writers’ motivations for using the pronouns ‘I’ and ‘we’ (and the perceived textual effects) in political science through both qualitative interviews. Previous studies on academic discourse have also suggested that the use of we is able to stimulate readers’ receptive attitude toward the writer’s claims (Harwood 2005b), and create a sense of shared space between writers and readers (Hyland 2001). Despite the extensive work undertaken to date on self-mention pronouns and their functions Identity construction and its networks 651 in academic discourse, their use in written workplace communication remains underexplored. Another important line of inquiry into authorial identity has centered on register-specific variation (Barbieri 2015; Biber 2006a, 2006b; Biber and Conrad 2009; Dong and Jiang 2019). A register is composed of “the linguistic features which are typically associated with a configuration of situational features—with particular values of the field, mode and tenor” (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 22). According to Biber (1998), registers can be distinguished by their linguistic features (among other factors), and the shared knowledge and use of such features within a specific register contribute to the identity of a given discourse community (Roberts and Sarangi 1999). Within this perspective, Molino (2018) investigated corporate identity construction through self-references in Vodafone’s sustainability reports, and found a high reliance on the first person plural pronoun (we) in this register. Using the metadiscourse framework, Ho (2018) identified that self-mention markers (i.e., I, we, our, and me), when compared with other types of metadiscourse markers, are most frequently used in workplace emails. Previous studies have typically been conducted from the perspective of the frequency of occurrence in a particular register. Few attempts have been made to tease out the semantic environments, that is, how self-mention markers are used in relation to the surrounding linguistic contexts. This study embraces this perspective by exploring how self-mention markers co-occur with specific semantic environments, that is, collocation networks. Such knowledge can add an additional layer of understanding to analyses of register variation. 2.3 Collocation networks Collocation-related studies investigate the relationship between a lexical item and its surrounding context. In addition to relative collocational strength, previous studies have focused on semantic prosody and semantic preference (Cortes and Hardy 2013; Partington 2004), and collocation networks (Brezina et al. 2015; Hoey 2005; Phillips 1989). The concept of collocation network, a term proposed by Phillips (1985, 1989), concerns the examination of the contextual interconnectedness of lexical items and their surrounding environment. This concept places a special emphasis on the conceptual relationship between linguistic items, and it thus allows us to map out how linguistic items co-occur with their surrounding contexts and how they contribute to constructing coherent texts. The software GraphColl (Brezina et al. 2015) was specifically designed to facilitate the creation and analysis of collocational networks. This tool clusters the collocates of a given node in a network. The collocates are retrieved by pre-set 652 Dong and Buckingham criteria based on collocational strength. The resulting visual display enables a thorough inspection of collocational relationships and collocational strength, which is indicated through the relative length of the line connecting the node with the collocate. This principled approach to identifying collocates can contribute to revealing possible “latent patterns” (Sinclair and Coulthard 1975: 125), which may not be salient when manually sifting through concordance lines. Drawing on this concept, previous studies have identified notable collocational patterns for particular linguistic items (Brezina et al. 2015; Gablasova et al. 2017) and phrases in cross-disciplinary academic discourse (Dong and Buckingham 2018). These studies have enriched our understanding of the semantic relatedness between linguistic features used by writers to construct their ideational and rhetorical objectives. 3 Data and methods 3.1 Corpora Our cross-register analysis employs a self-built academic discourse corpus and the Hong Kong Financial Services Corpus (HKFSC). The finance academic corpus (FAC) consists of 120 research articles published in ten high-ranking peer-reviewed journals, which were selected by considering the nomination of disciplinary experts, and contains 1,627,958 tokens. The list of the journals is presented in the Appendix. The HKFSC consists of 25 sub-registers including annual reports, brochures, bank service charges, etc., which represents the most common workplace discourse in the financial services industry in Hong Kong (Li and Qian 2010). This corpus has been used previously to explore lexical items used in written texts of the finance workplace (Li and Qian 2010). The corpus is periodically updated, and the version we employ comprises 7,341,937 tokens; additional information regarding the corpus is presented in Table 1. Information regarding the authors of the workplace texts is not accessible for ethical reasons. According to the compilers of HKFSC (personal communication, March 2019), these texts circulated in the professional workplace and represent the common or shared community practices in the workplace setting of the finance business. To strengthen the comparability of the workplace and the academic discourse corpora with respect to authorship, we randomly selected the articles for the academic discourse corpus in order to reflect common authorship practices, rather than purposely controlling for single-authored and co-authored papers. Furthermore, to take into account important differences between written and spoken texts (Biber 2006a, 2006b; Biber and Barbieri 2007), we limited our analysis Identity construction and its networks 653 Table : Components of the HKFSC. Corpus Annual reports Brochures Bank service charges Codes Corporate announcements Circulars Fund descriptions Fund reports Factsheets Guidelines General meetings Insurance policies Interim reports Insurance product descriptions Investment product descriptions Model agreements Media releases Ordinances Procedures Principles Prospectuses Rules Results announcements Standards Speeches Size ,, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,, , , , , to written texts in the workplace corpus. This meant omitting the text type ‘speeches’ from the HKFSC. This reduced the size of the HKFSC to 6,731,965 tokens, and 3,438 text samples. 3.2 Retrieval of the self-mention pronouns To identify and extract instances of the first person pronoun (singular and plural), we followed Hyland (2001) and Tang and John (1999), who looked at the first person pronouns we, us, I, me, our, my,1 ours, and mine, but we also included the 1 Although “my” is not a personal pronoun in grammatical terms (but rather a possessive adjective), we followed the previous practices and included this in the analysis to better represent the use of self-mention. 654 Dong and Buckingham pronouns ourselves, myself to ensure that the exploration was as comprehensive as possible. This step was carried out by using the advanced search function of Antconc (Anthony 2018) to retrieve all occurrences of the aforementioned pre-set list of pronouns. Subsequently, we undertook a manual examination of the concordance lines in order to ensure the results were limited to personal pronouns. For example, the results included cases such as I in Experiment I, Investigator I, and mine (noun) in the Luanchuan mine has an estimated annual production capacity of 90,000 tonnes of iron ore. Examples such as these were excluded. 3.3 Collocate retrieval To address Research Question 2, the retrieval of the collocates and the collocation networks of the self-mention pronouns was carried out using Graphcoll (Brezina et al. 2015). In this study, we used the parameter of both Mutual Information (MI) and frequency to measure the collocational networks. The MI value was set at >3 (in line with Gablasova et al. 2017 and Brezina et al. 2015), and frequency was set at >5 instances per million words on each side of the node words for broad coverage of the collocates for our analysis. The two measures have been generally viewed as robust approaches to calculating collocational strength (e.g., Ellis et al. 2008; McEnery 2006). We limited the collocational span to five words on each side of the selfmention pronouns following McEnery (2006) and Brezina et al. (2015). The collocational span permits us to investigate both immediate and non-immediate collocates (Sinclair et al. 2004: 42), namely the collocates that are adjacent and nonadjacent to the node words or phrases, which is adequate to identify and analyze the collocational patterns of self-mention pronouns under scrutiny in this study. 3.4 Analytical procedure In order to report the general features of these collocation networks, we used Wmatrix (Rayson 2008) to tag the collocates and assign a semantic label to the collocates retrieved. This semantic analytical tool is generally accepted as “a robust tool for automating semantic field” (Lu 2014: 148). In the analysis, we loaded the collocates retrieved by GraphColl to the online Wmatrix analyzer, and this analyzer assigned the semantic tagger to each collocate. Wmatrix assigns semantic labels to words according to their dictionary meanings; as a result, some collocates are assigned multiple meanings. Identity construction and its networks 655 For cases with multiple semantic labels, we examined the concordance lines to identify the appropriate labels. For example, the item present was tagged with three labels: ‘Time’, ‘Social actions, states, and processes,’ and ‘General action’. We manually selected the category ‘Time’ for examples such as our present study; for the example we present a model, we assigned the category label ‘General action’. With respect to the acronyms labeled by Wmatrix, we examined the concordance lines to identify their original full meanings and subsequently assigned a tag. For example, CLP was identified to be a company name as in ‘CLP Holdings Limited’, an investment holding company. This was tagged as a proper noun, which falls under the general category of ‘Z’ (‘Names and grammatical words’). To ensure the reliability of the identification of multiple semantic labels, the first author first went through all the collocates and identified the semantic labels for each collocate, and then 30% of the collocates were tagged by referring to the labels given by Wmatrix by the second author. We measured the two ratings using Cohen’s kappa, and the coefficient was 0.92 (p < 0.001), which indicates a high agreement on the semantic labels used in this study. When comparing the register-specific features, a Chi-square test of group independence was employed to compare both the occurrences and the collocation networks of the self-mention pronouns in the two corpora. Following recommendations in Young and Karr (2011) for multiple tests, p values were corrected as follows. In the first case (a series of 10 tests), the alpha value was corrected to 0.05/10 = 0.005; in the second case (a series of 13 tests), the alpha value was corrected to 0.05/13 = 0.0038. We used Cohen’s w (Cohen 1998) to calculate the effect size for the Chi-square test and the results were interpreted following Cohen’s (1998) magnitude guidelines, that is, a value of 0.1 and below is considered a small effect, between 0.1 and 0.5 a medium effect, and values of 0.5 and above a large effect. 4 Results and analytical findings 4.1 Frequency of self-mention pronouns and functional uses The overall frequency comparison of the self-mention pronouns is presented in Table 2. As shown, the overall occurrences of the first person pronoun plural – we, us, our, ours and ourselves – are much higher than the occurrences of the first person pronoun singular (I, me, myself, mine, and my), with an occurrence of 9,879.24 and 128.99 per million respectively for the collective and individual self-mention pronouns in the academic corpus. This preference for expressing 656 Dong and Buckingham Table : Comparison of the academic and workplace written texts. Pronouns Academic norm (raw) freq Workplace norm (raw) freq Chi-square Sig Effect size Mine Me Ours Myself We Us Ourselves My Our I . () . () . () . () ,. (,) . () . () . () ,. (,) . () . (.) . (.) . () . () ,. (,) . (,) . () . () ,. (,) . () . . . . ,. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. . . Total To match the calculated p value as discussed in Section ., we present the results with three decimal places in the sig column. the self in collective terms can be explained by the tendency towards co-authorship in the finance RAs. This finding is in line with Mur Dueñas (2010), who also identified a prevalence of co-authorship in the adjacent discipline of business management. A similar preference for first-person plural pronouns is manifested in the workplace texts from the finance sector: the overall frequency of collective and individual self-mention pronouns is 5,497.28 and 47.24 per million respectively. As previously noted in Blitvich (2010), Bernard (2015), and Molino (2018), the collective reference is a dominant form of corporate identity construction in business workplace discourse. Examples (1) and (2)2 illustrate scenarios where the collective self is used in the workplace written texts to express corporate identity in undertaking the stipulated activity exceeded our earnings objective, and conduct our audit. Such combinations allow the writers to present themselves as competent community members, and thereby engage with readers in a community-appropriate manner. (1) We exceeded our earnings objective, with core earnings per share of $3.92, a 7% increase. This includes a 4% headwind from foreign exchange. (AR-HKFSC) 2 The examples were randomly selected to illustrate the meanings described. Identity construction and its networks (2) 657 At the same time, we have made significant progress in our efforts to improve corporate governance. (RA-HKFSC) The examples above show that individual self my is often presented together with expressions showing a collective group identity, i.e., my colleague, as in Example (3). This provides further evidence for the importance of the collaborative self in the workplace written texts. By associating the individual self with the collective self, writers make explicit their group identity. (3) The achievement of this strategy requires the effective management by my colleagues and I, under the direction of the Board, of a number of key implementation issues. (AR-HKFSC) Aside from this similarity, the two registers were also found to display significant differences in the frequency of almost all the self-mention pronouns, except I, mine, and myself. They proved to be significantly more frequent in the academic corpus, with a frequency approaching two times that of the workplace written texts (p < 0.001), and with a large effect size (w = 0.59). This indicates that the difference in frequency of the use of self-mention pronouns can, to a large extent, be explained by the difference in registers. That is, finance academic texts are much more likely to contain an explicit manifestation of authors’ presence than workplace texts. The pronouns we, our, and us were the top three most frequent self-mention pronouns in the two registers. However, in many instances, considerable differences between the two registers were found in the frequency of the ten different types of self-mention pronouns under analysis. The pronoun we occurred more than three times more frequently in the academic corpus than in the workplace written texts; this difference was significant (p < 0.001) and the effect size was large (w = 1.18). This indicates that difference in frequency can to a great extent be attributed to register specificity. Example (4) illustrates the writer’s agentive role in performing an action, namely analyze spam-related SEC enforcement action. The combination of cognitive involvement in tandem with the collective self (we) allows writers to make explicit their active involvement in terms of analyzing spam-related SEC enforcement action. (4) To provide insights into the motivations for operating a stock spam scheme and the costs and benefits involved, we analyse spam-related SEC enforcement action. (FAC) In contrast, we identified a significantly higher rate of occurrence of our in the workplace written texts, with a frequency of 3,241.81 and 2,671.44, respectively, in the workplace and academic registers (p < 0.001), but the magnitude of variation 658 Dong and Buckingham was very small (w = 0.08). In (5), our is used to express the collective self in conjunction with nouns such as ability, growth, level of success, and gold mines. Through the reiterated use of possessive adjective self-mention pronouns, writers are able to underscore their presence in the text. (5) Our ability to achieve our growth objectives is dependent on our level of success in discovering or acquiring additional gold resources and further exploring our current gold mines. (Pro-HKFSC) The pronoun us was found to occur significantly more frequently in workplace discourse (p < 0.001), and the large effect size (w = 1.14) points to the magnitude of this variation in the two corpora. An in-depth analysis of the concordance lines of us in the workplace corpus shows that this self-mention pronoun is used to perform the following three main discourse functions: namely ‘us’ used as an indirect object (e.g., provide us with sufficient evidence); ‘us’ used as a prepositional complement (e.g., there has been no impact on us); and ‘us’ used as a direct object (e.g., our commitment to education enables us to provide our customers with industry-leading products and services). Of these, the use of ‘us’ as an indirect object is the most dominant form, accounting for 72.95% of all usages. In contrast, the use as a prepositional complement and direct object accounted for 21.2% and 5.93% of all uses respectively. This shows that the workplace written texts are more likely to present authors in the beneficiary or receiver role when compared to findings from the academic corpus. For instance, in Example (6) us is used as the recipient of the information and representation provided by the company. (6) We have no reason to doubt the truth, accuracy and completeness of the information and representation provided to us by the Company. (HKFSC-Cir) 4.2 The collocation networks of self-mention pronouns Figures 1 and 2 depict the collocation networks of self-mention pronouns in the academic and workplace corpora respectively. In these two figures, the central dots represent the self-mention pronouns, and the surrounding dots show the collocates of self-mention pronouns. The distances between the stance nodes and each collocate indicate the strength of the collocational bond. That is, the shorter the distance between two collocating items, the greater the collocation strength, and vice versa. The positioning of the stance nodes (i.e., market, samples, and businesses) in relation to one another is random in these figures. Identity construction and its networks 659 Figure 1: The collocation network of self-mention pronouns in the academic register. Figure 2: The collocation network of self-mention pronouns in the workplace written texts. The graph presented in Figures 1 and 2 was obtained by adopting a higher threshold (namely MI > 3, Normalized frequency > 150) than the one adopted for the statistical analysis of the data in order to facilitate the visual display of data in this figure. Table 3 displays the statistical comparison of semantic categories that appear in the networks of self-mention pronouns in the two registers. A significant variance was found for all thirteen categories in the two corpora. More notable, however, is the magnitude of variance. Five categories were found to have large effect sizes, six categories were at a medium level of significance, and . (,) ,. (,) . (,) . (,) ,. (,) . () ,. (,) . (,) . (,) ,. (,) . () . (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) . (,) ,. (,) . () ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) . () ,. (,) ,. (,) ,. (,) Linguistic actions, states, or process Number and measurement Psychological actions, states, and process Government General actions or entities Science and technology Names and grammatical words Movement Substances and materials Social actions, states, and processes Emotion Time Money and commerce Total The categories discussed in the text are displayed in bold. Workplace norm (raw) freq Academic norm (raw) freq Semantic categories Table : Comparison of semantic categories in the academic and workplace written texts. ,. ,. ,. ,. . ,. . ,. . . . . . . Chi-square . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Sig . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Effect size 660 Dong and Buckingham Identity construction and its networks 661 two were at a small level of significance. In all cases except two (‘movement’ and ‘social actions, states, and processes’), the semantic domains appeared more frequently in the academic corpus. Due to space constraints, we direct our focus to the notable collocational patterns of the top five semantic categories (excluding the grammatical words), which were identified by considering both effect size and total normalized frequency. 4.2.1 General action and entities As shown in Table 3, the ‘General actions or entities’ category occurs most frequently in both corpora. The statistical comparison also shows that the academic corpus contains a significantly higher use of this category in the surrounding context of self-mention pronouns (w = 0.73, p < 0.001). Aside from the variation in frequency, we also found notable differences in the specific collocates within this category. For instance, the academic discourse corpus was found to contain significantly more research-related expressions, such as sample, results, research, study, and results, co-occurring with the self-mention pronouns, particularly in conjunction with the possessive determiners (our). This is in line with the role of self-mention pronouns in stressing the ownership of the work, a function that has been identified by Hyland (2001) and Harwood (2005a). Another notable type of collocate which occurs in the collocation networks of the self-mention pronouns is action verbs, such as find, obtain, change. This type of expression is found to frequently collocate with the personal pronouns in nominal form. Examples (7) and (8) illustrate two such instances where the authors explicitly manifest their presence in relation to the research-related entity (results) and their activity ( find) to underscore their involvement in research-oriented actions. Here, the juxtaposition of the pronoun with the two research-related expressions allows the academic writers to claim their ownership of the results and active involvement in the upcoming claims. This active involvement thus serves as evidential support for the knowledge constructed in the following statement, and thus contributes to promoting the findings of their study. (7) Taken together, our results suggest that while on the whole adherence to the Codeâs voluntary recommendations has strengthened the monitoring capacity of the boards of listed firms in UK, …. (FAC) (8) We find that all three variables have significant pricing effects, indicating each conveys information content. (FAC) 662 Dong and Buckingham The collocation networks of pronouns in the workplace written texts, however, are composed of a substantial number of workplace nouns including development, quality, activities, production, and ‘general action’ verbs, such as continue, provide, maintain. This shows that workplace writers tend to position themselves in relation to workplace-related processes. Example (9) illustrates how the writers convey the roles they perform by asserting we provide service to our customers; while (10) illustrates how the writers signal the intrinsic positive value of their work (our quality and reliability). By claiming the ownership of corporate banking customers and quality and reliability, the writers are able to mark an explicit presence and underscore their role in communication with envisaged readers. (9) In addition, we provide international settlement service to our corporate banking customers. (Prospectus–HKFSC) (10) Through the implementation and regular review of the Quality Management System, we strive continuously to improve our quality and reliability, … (Annual Report–HKFSC) 4.2.2 Psychological actions, states, and processes Another notable collocation network concerns the ‘Psychological actions, states, and process’, which entails authors’ cognitive processing of the information. The statistical analysis shows a significantly higher occurrence of cognitive markers in the collocating networks of the academic corpus ( p < 0.001), and the large effect size (w = 1.02) indicates the extent of the magnitude of this variance. Among the most frequently occurring cognitive verbs, we find a substantial number of cognitive expressions, such as examine, expect, estimate, assume, consider. According to Hyland (2017), cognitive verbs entail writers’ cognitive involvement in constructing an argument and persuading readers. Example (11) illustrates this collocational relationship between the collective self and the cognitive action (analyze). By explicitly projecting themselves in juxtaposition with the cognitive behavior (analyze), the writers are able to manifest their cognitive involvement in processing the data, and thus gain credit for their involvement and contribution in carrying out the analysis. (11) In addition, our unique hand-collected data on finite life and indefinite life IIA allow us to further analyse the managerial discretion involved in the classification of such assets. (FAC). Apart from the frequency differences, the analysis of the category ‘Psychological actions, states, and processes’ in the workplace written texts shows that the Identity construction and its networks 663 writers tend to draw upon a different set of cognitive collocates. For instance, expressions such as believe and expect are among the most frequent psychological expressions in this workplace discourse, as shown in (12). In this example, the writers express a cognitive action believe the continuous deregulation of IPTV undertaken by the collective self (we). This collocational pattern indicates that the writers in the workplace corpus are more likely to position themselves as ‘opinion holders’, a function of self-mention pronouns identified by Tang and John (1999). (12) We believe the continuous deregulation of IPTV will provide outstanding opportunities for the Company to develop broadband applications and content services, as well as drive the “PC+TV” and “charging for access+content” broadband business model to a greater degree of maturity. (RA-HKFSC) (Prospectus-HKFSC) 4.2.3 Social actions, states, and processes As shown in Table 2, the expressions concerning ‘Social actions, states, and processes’ also constitute a notable component of the collocation networks of selfmention pronouns of both corpora. The cross-corpora comparison shows that the social expressions are significantly more frequently used in the workplace written texts (p < 0.001), with a medium effect size (w = 0.36). That is, the variance in the two corpora with regard to the use of social expressions can to a moderate degree be explained by the difference in register. An inspection of the specific collocates revealed that the workplace written texts contain more expressions related to workplace entities and social actions. For example, management, services, corporate, directors, and board are among the top collocates which occur in the vicinity of self-mention pronouns. In Example (13), we see a case in which our is associated with the social-oriented noun, management, and is preceded by further social-related nouns (services and properties). This serves as a good indicator of the social attachment found in the surrounding context of the possessive adjective pronoun. (13) While the contribution from property management is not significant, the Group is committed to providing top quality services to properties under our management. 664 Dong and Buckingham 4.2.4 Number and measurement As shown in Table 3, the collocation networks of self-mention pronouns are also composed of a substantial number of collocates denoting ‘number and measurement’. The occurrence of this type is seen to be significantly higher in the collocation networks of the academic corpus (p < 0.001), and the effect size is large (w = 1.07). In the list of most frequent collocates, we see a high occurrence of all, each, first, and measure. This shows that academic writers are more inclined to project their explicit presence in relation to the expressions denoting number and measurement. In Example (14), we see the combination of the number or measurement-related expressions, including calculate, average and all, with we, and the two linguistic features collocate strongly. Clearly, we shares a strong collocation with the measurement verbs (calculate and average). The quantifier (all) occurred as a component in the noun phrase, all the unaffiliated forecasts, which functions as the object of the self-mention subject (we). In the workplace texts, we find a high occurrence of measurement expressions like, total, more, most and in most cases these collocate with the self-mention pronouns. This is illustrated in (15) with our. (14) To calculate the consensus, we average all the unaffiliated forecasts for a given firm issued within a calendar month and before the affiliated analyst’s. (FAC) (15) Our total revenue reached a record high of RMB48.3 billion, representing an increase of 47.2% as compared with the same period last year. 4.2.5 Linguistic actions, states or process3 In the collocation network of self-mention pronouns, we identified a high density of linguistic expressions and actions, such as table, paper, discuss, and describe, as illustrated in (16). (16) In this section we discuss the results of alternate specifications of the portfolio time series regression tests reported in Sections V, VI, and VIII. (FAC) The cross-corpora comparison shows that the academic corpus contains a significantly higher occurrence of this category in the collocation networks of selfmention pronouns (p < 0.001) and the effect size is large (w = 1.54). This suggests 3 This category also includes entities or terms relating to written communication. Identity construction and its networks 665 that finance academics are more inclined to manifest their presence through linguistic actions than the workplace writers. Also of note, we identified that this category is primarily composed of reporting verbs (i.e., discuss, describe, express). In contrast, the linguistic expressions in the collocation networks of the workplace written texts occur less frequently and are composed of a different set of reporting expressions, including report, statements, said, article, terms, advise. Example (17) shows an instance where the writers juxtapose the self-mention subject (we) in tandem with the linguistic action ‘report’, thereby making explicit their involvement in the linguistic-oriented action. (17) We report on the unaudited pro forma financial information of Bank of Communications Co., Ltd. (Prospectus-HKFSC) Overall, both corpora also displayed significant differences with respect to the semantic categories in the collocation networks of the self-mention expressions. The cross-corpora comparison shows that the academic corpus contains a substantially higher use of general actions or entities, linguistic actions and number or measurement-related actions, while the workplace corpus displays a higher use of social expressions. 5 Conclusion The analysis from the perspective of collocation networks enabled us to identify a number of latent semantic patterns that co-occur with self-mention pronouns, such as the psychological, social, and linguistic-related expressions. By mapping out the self-mention pronouns and their collocation networks, we were able to identify how professional writers in each register construct their textual presence in alignment with their discursive community practices, the surrounding semantic contexts, and the communitive purposes embedded in the discourse. In a context of increasing student enrollments in this field, practitioners have noted the need to develop students’ discipline-specific literacy skills for workplace purposes (Bernheim and Garrett 2003; Kavanagh and Drennan 2008). The findings thus have practical implications for our understanding of the meaning of both academic and workplace communicative competence, and for shaping teaching materials or curriculum design to prepare students for professional career paths (Hyland 2015; Lam et al. 2019). Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the findings in this study are limited to just one aspect of the features of identity construction. As previous studies have 666 Dong and Buckingham noted (i.e., Coupland 2007; Dong and Buckingham 2020; Hyland 2015), identity construction is a complex concept and process, and it can be embedded in a wide range of linguistic devices other than pronouns (such as, ‘the authors of the present work’ or ‘this organization’s leadership’). For a more comprehensive treatment of this concept, future work may need to include other linguistic forms of identity construction. In addition, the social attributes of writers or their anticipated readership may also shape the discursive construction of identity, as was shown by Blitvich’s (2010) differentiation between external and internal oriented discourse. Finally, it is necessary to acknowledge that the workplace corpus consists of 25 sub-registers, and linguistic features may vary at the level of the sub-register. In the comparisons undertaken in this study, we chose to group the self-mention pronouns and their collocational patterns in each corpus. Although this approach enabled us to obtain a general view of the self-mention markers and their semantic collocational relationship with the surrounding texts, it is not conducive to identifying possible variations in the frequency of specific pronouns, and in the individual sub-registers or texts. Research funding: This study received financial support from the Taishan Young Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (No. 201909048) and the Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2020K025). Appendix List of the journals used for the finance academic corpus. – – – – – – – – – – Journal of Finance Journal of Corporate Finance Journal of Financial Economics Journal of Accounting and Economics Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis Journal of Banking and Finance Journal of Money Credit and Banking Journal of International Money and Finance Journal of Business Finance & Accounting Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting Identity construction and its networks 667 References Anthony, Lawrence. 2018. AntConc (Version 3.5.7) [Computer Software]. Tokyo, Japan: Waseda University. Available at: http://www.laurenceanthony.net/software. Balmer, John J. M. 2008. Identity based views of the corporation: Insights from corporate identity, organisational identity, social identity, visual identity, corporate brand identity and corporate image. European Journal of Marketing 2(9/10). 879–906. Barbieri, Federica. 2015. Involvement in university classroom discourse: Register variation and interactivity. Applied Linguistics 36(2). 151–173. Baxter, Judith. 2010. The language of female leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave. Bazerman, Charles. 2010. The informed writer: Using sources in the disciplines. Fort Collins, Colorado: Houghton Mifflin Company. Becher, Tony & Paul Trowler. 2001. Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual inquiry and the culture of disciplines. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bernard, Taryn. 2015. A critical analysis of corporate reports that articulate corporate social responsibility. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University Doctoral Dissertation. http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/96672 (accessed October 2018). Bernheim, B. Douglas & Danie M. Garrett. 2003. The effects of financial education in the workplace: Evidence from a survey of households. Journal of Public Economics 87(7–8). 1487–1519. Biber, Douglas. 1998. Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Biber, Douglas. 2006a. Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5(2). 97–116. Biber, Douglas. 2006b. University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Biber, Douglas & Federica Barbieri. 2007. Lexical bundles in university spoken and written registers. English for Specific Purposes 26(3). 263–286. Biber, Douglas & Susan Conrad. 2009. Register, genre, and style (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Blitvich, Pilar, G. 2010. Who “we” are: The construction of American corporate identity in the corporate value statements genre. In Miguel Ruiz-Garrido, Juan Palmer-Silveria & Inmaculada Fortanet-Gomez (eds.), English for professional and academic purposes, 121–137. Amsterdam: Rodopi. Breeze, Ruth. 2013. Corporate discourse. London: Bloomsbury. Brezina, Vaclav, Tony McEnery & Stephen Wattam. 2015. Collocations in context: A new perspective on collocation networks. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 20(2). 139–173. Cohen, Seymour Stanley. 1998. Guide to the polyamines. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cortes, Vivian & Jack Hardy. 2013. Analyzing the semantic prosody and semantic preference of lexical bundles. In Diane Belcher & Gayle Nelson (eds.), Critical and corpus-based approaches to intercultural rhetoric, 180–201. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. Coupland, Nikolas. 2007. Style: Language variation and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Djordjilovic, Olga. 2012. Displaying and developing team identity in workplace meetings–a multimodal perspective. Discourse Studies 14(1). 111–127. 668 Dong and Buckingham Dong, Jihua & Louisa Buckingham. 2018. The collocation networks of stance phrases. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 36. 119–131. Dong, Jihua & Louisa Buckingham. 2020. Stance phraseology in academic discourse: Cross-disciplinary variation in authors’ presence. Ibérica 39(Spring). 191–214. Dong, Jihua & Feng Jiang. 2019. Construing evaluation through patterns: Register-specific variations of the introductory it pattern. Australian Journal of Linguistics 39(1). 32–56. Ellis, Nick, Rita Simpson‐Vlach & Carson Maynard. 2008. Formulaic language in native and second language speakers: Psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 42(3). 375–396. Gablasova, Dana, Vaclav Brezina & Tony McEnery. 2017. Collocations in corpus-based language learning research: Identifying, comparing, and interpreting the evidence. Language Learning 67(1). 1–25. Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman. Harwood, Nigel. 2005a. “Nowhere has anyone attempted … In this article I aim to do just that”: A corpus-based study of self-promotional I and we in academic writing across four disciplines. Journal of Pragmatics 37(8). 1207–1231. Harwood, Nigel. 2005b. ‘We do not seem to have a theory… The theory I present here attempts to fill this gap’: Inclusive and exclusive pronouns in academic writing. Applied Linguistics 26(3). 343–375. Harwood, Nigel. 2006. (In)appropriate personal pronoun use in political science: A qualitative study and a proposed heuristic for future research. Written Communication 23(4). 424–450. Harwood, Nigel. 2007. Political scientists on the functions of personal pronouns in their writing: An interview-based study of ‘I’ and ‘we’. Text & Talk 27(1). 27–54. Ho, Victor. 2018. Using metadiscourse in making persuasive attempts through workplace request emails. Journal of Pragmatics 134. 70–81. Hoey, Michael. 2005. Lexical priming: A new theory of words and language. London: Routledge. Hyland, Ken. 2001. Humble servants of the discipline? Self-mention in research articles. English for Specific Purposes 20. 207–226. Hyland, Ken. 2002. Authority and invisibility: Authorial identity in academic writing. Journal of Pragmatics 34(8). 1091–1112. Hyland, Ken. 2015. Genre, discipline and identity. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 19. 32–43. Hyland, Ken. 2017. Metadiscourse: What is it and where is it going? Journal of Pragmatics 113. 16–29. Hymes, Dell. 1984. Sociolinguistics: Stability and consolidation. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 45. 39–46. Ivanič, Roz. 1998. Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Kavanagh, Marie H. & Lyndal Drennan. 2008. What skills and attributes does an accounting graduate need? Evidence from student perceptions and employer expectations. Accounting and Finance 48(2). 279–300. Kuo, Chih-Hua. 1999. The use of personal pronouns: Role relationships in scientific journal articles. English for Specific Purposes 18. 121–138. Lam, Phoenix W. Y., Winnie Cheng & Kenneth C. C. Kong. 2019. Learning English through workplace communication: Linguistic devices for interpersonal meaning in textbooks in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes 55. 28–39. Identity construction and its networks 669 Li, Yongyan & David D. Qian. 2010. Profiling the academic word list (AWL) in a financial corpus. System 38(3). 402–411. Lu, Xiaofei. 2014. Computational methods for corpus annotation and analysis. Dordrecht: Springer. Matsuda, Paul Kei & Christine M. Tardy. 2007. English for voice in academic writing: The rhetorical construction of author identity in blind manuscript review. English for Specific Purposes 26. 235–249. Mattioda, Maria Margherita & Marie Berthe Vittoz. 2014. The making of corporate identities through a plural corporate language, A comparative study on French and Italian food companies. RiCOGNIZIONI. Rivista di lingue, letterature culture moderne 1(1). 239–252. McEnery, Tony. 2006. Swearing in English: Bad language, purity and power from 1586 to the present. London: Routledge. McGrath, Lisa. 2016. Self-mentions in anthropology and history research articles: Variation between and within disciplines. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 2. 86–98. Molino, Alessandra. 2018. Corporate identity and its variation over time: A corpus-assisted study of self-presentation strategies in Vodafone’s sustainability reports. In Viola Wiegand & Michaela Mahlberg (eds.), Corpus linguistics, context and culture, 75–108. Berlin: De Gruyter. Moore, Tim & Janne Morton. 2017. The myth of job readiness? Written communication, employability, and the “skills gap” in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 42(3). 591–609. Mullany, Louise. 2007. Gendered discourse in the professional workplace. New York: Palgrave. Mur Dueñas, Pilar. 2007. “I/we focus on…”: A cross-cultural analysis of self-mentions in business management research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6(2). 143–162. Mur Dueñas, Pilar. 2010. Attitude markers in business management research articles: A crosscultural corpus-driven approach. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 20(1). 50–72. Partington, Alan. 2004. “Utterly content in each other’s company”: Semantic prosody and semantic preference. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 9(1). 131–156. Phillips, Martin. 1985. Aspects of text structure: An investigation of the lexical organisation of text. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Phillips, Martin. 1989. Lexical structure of text [Discourse Analysis Monograph 12]. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Dissertation. Rayson, Paul. 2008. From key words to key semantic domains. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 13(4). 519–549. Roberts, Celia & Srikant Sarangi. 1999. Hybridity in gatekeeping discourse: Issues of practical relevance for the researcher. In Srikant Sarangi & Celia Roberts (eds.), Talk, work and institutional order: Discourse in medical, mediation and management settings, 473–503. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Sheldon, Elena. 2009. From one I to another: Discursive construction of self-representation in English and Castilian Spanish research articles. English for Specific Purposes 28(4). 251–265. Sinclair, John & Malcolm Coulthard. 1975. Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sinclair, John, Susan Jones & Robert Daley. 2004. English collocation studies: The OSTI report. London: Continuum. 670 Dong and Buckingham Tang, Ramona & Suganth John. 1999. The “I” in identity: Exploring writer identity in student academic writing through the first person pronoun. English for Specific Purposes 18. S23–S39. Young, Stanley & Alan Karr. 2011. Deming, data and observational studies: A process out of control and needing fixing. Significance 8(3). 116–120. Bionotes Jihua Dong The School of Foreign Languages and Literature, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China dongjihua@sdu.edu.cn Jihua Dong is Professor, Taishan Young Scholar and Qilu Young Scholar in the Foreign Language Department, Shandong University, China. She obtained her PhD degree from the University of Auckland, New Zealand. Her research interests are Corpus Linguistics, Cross-disciplinary Studies, and English for Academic/Specific Purposes (EAP/ESP). She has published in journals such as International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, English for Specific Purposes, System, and Australian Journal of Linguistics. Louisa Buckingham The School of Cultures, Languages and Linguistics, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand l.buckingham@auckland.ac.nz Louisa Buckingham lectures in Applied Language Studies at the University of Auckland. She has a broad range of research interests which include the use of corpus linguistic discourse analysis. She has published in various journals including TESOL Quarterly, System, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, English for Specific Purposes, and Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development.