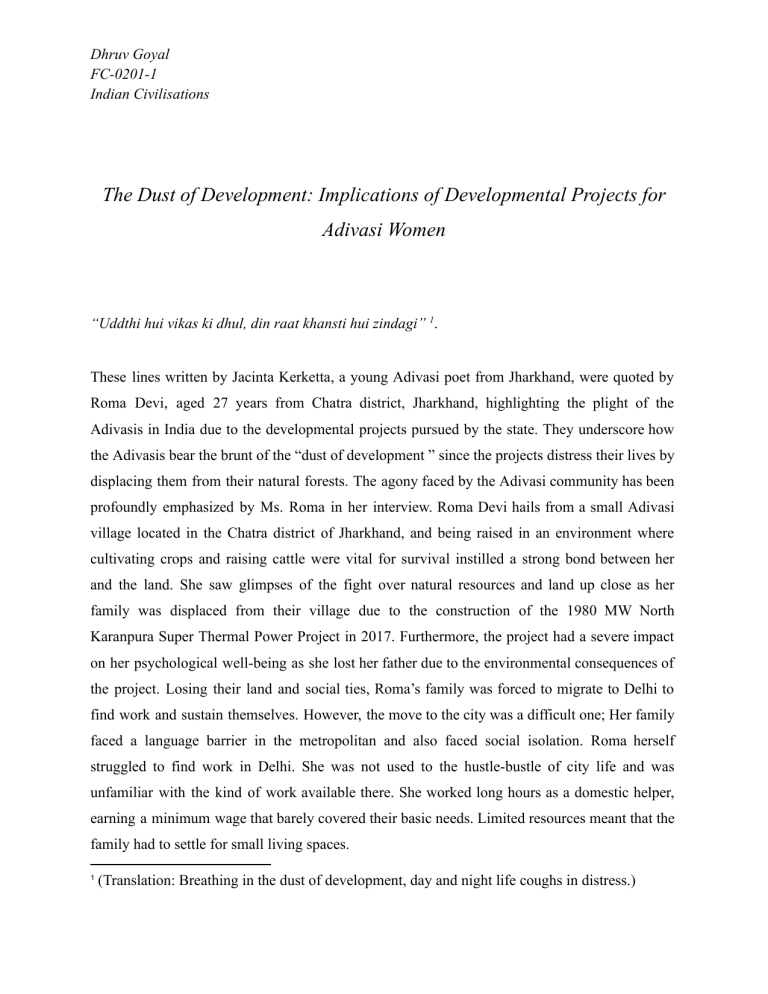

Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations The Dust of Development: Implications of Developmental Projects for Adivasi Women “Uddthi hui vikas ki dhul, din raat khansti hui zindagi” 1. These lines written by Jacinta Kerketta, a young Adivasi poet from Jharkhand, were quoted by Roma Devi, aged 27 years from Chatra district, Jharkhand, highlighting the plight of the Adivasis in India due to the developmental projects pursued by the state. They underscore how the Adivasis bear the brunt of the “dust of development ” since the projects distress their lives by displacing them from their natural forests. The agony faced by the Adivasi community has been profoundly emphasized by Ms. Roma in her interview. Roma Devi hails from a small Adivasi village located in the Chatra district of Jharkhand, and being raised in an environment where cultivating crops and raising cattle were vital for survival instilled a strong bond between her and the land. She saw glimpses of the fight over natural resources and land up close as her family was displaced from their village due to the construction of the 1980 MW North Karanpura Super Thermal Power Project in 2017. Furthermore, the project had a severe impact on her psychological well-being as she lost her father due to the environmental consequences of the project. Losing their land and social ties, Roma’s family was forced to migrate to Delhi to find work and sustain themselves. However, the move to the city was a difficult one; Her family faced a language barrier in the metropolitan and also faced social isolation. Roma herself struggled to find work in Delhi. She was not used to the hustle-bustle of city life and was unfamiliar with the kind of work available there. She worked long hours as a domestic helper, earning a minimum wage that barely covered their basic needs. Limited resources meant that the family had to settle for small living spaces. 1 (Translation: Breathing in the dust of development, day and night life coughs in distress.) Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations Adivasis are amongst the most vulnerable and marginalized socio-economic groups in India. Multiple natural resources and strong community ties make their life possible; however, due to the arrival of mining corporations, multinational companies, and state-funded developmental projects, their circumstances have been worsened. (Debasree, 2015) Historically, Adivasis have witnessed injustices against their livelihood, social, and cultural systems as the colonial government exploited the nation as a supplier of capital and raw materials to meet the needs of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. Beginning in the nineteenth century, colonialists in pursuit of this goal started opening coal mines in Raniganj, coffee plantations in Karnataka, tea gardens in Assam, etc. (Mankodi 1989) The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 gave the state power to annex individual land and did not provide compensation to those dependent on the resources for sustenance such as landless laborers. Post-independence, this development-induced displacement has only intensified with the onset of globalization. The state has inflicted economic and social violence on Adivasis in pursuit of economic growth and development. Their well-being and means of subsistence have been severely impacted by multiple forms of violence, ranging from coerced uprooting to environmental degradation. The interview with Roma Devi highlighted the gendered marginalization of Adivasi women in the post-displacement setup. It conveyed that the effects of the developmental projects are not homogeneous across men and women. Studies on development-induced displacement have primarily focused on the marginalization of the Adivasi community as a whole, instead of understanding how it affects Adivasi women in particular. Through the narratives provided by Ms. Roma, this paper argues that the larger account of development-induced displacement in India does not comprise the impact that it has on Adivasi women who are the key stakeholders of their local ecology. It underlines how the developmental projects pursued by the state and private sector have led to the intense economic and social marginalization of Adivasi women in India. Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations “Plant banane ke liye sarkar ne humari zameen hadapli thi. Patwari ne aake humara ghar tudwa diya yeh bolke ki hume doosri zameen dedi jaigi. Humne iss behkave mai aake, apni zameen unhe dedi. Saalon tak sarkar ne humare parivar ko nayi zameen nahi di. Mere parviaar ke paas, apni zameen ke alawa kuch nahi tha. Hume apna pet bharne ke liye, yahaan (Delhi) aana hi tha.”2 20 tribal villages, including Ms. Roma’s, had to make way for the North Karanpura Super Thermal Power Plant set up by the National Thermal Power Plant Corporation (NTPC). The same year, the government passed the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement (Jharkhand Amendment Bill) 2017. This bill allowed the state to make use of tribal land for non-agricultural purposes which also legitimized the Adivasi displacement in Chatra. As quoted by Ms. Roma, the NTPC power plant affected the economic security of her family by taking away the land that gave them work, leading to their landlessness and subsequent joblessness. In addition, the poor resettlement and rehabilitation left them with no further alternatives. Many who were supposed to be covered under the Resettlement and Rehabilitation (R&R) package were subjected to economic victimization. Many, like Ms. Roma’s family, were not given the compensation that they were promised, while others were classified as “encroachers” on state land as they did not have any legal title to it. This builds on Fernandes’s claim that displacement takes displaced persons, particularly the most powerless amongst them, “beyond impoverishment to marginalization.” Projects such as the construction of power plants lead to landlessness and subsequent joblessness for Adivasis by taking away the land that gave them a livelihood and leaving them with no further alternatives. Consequently, they are forced to migrate to cities to look for jobs and sustain themselves. However, they possess skills and knowledge relating to their ecological niches and common pool resources. Since they are not trained to handle jobs in the formal Translation: “The government has seized our land to build the power plant. The government official ordered a demolition of our property, saying that we will be given new land. We took his word and gave our land to them, only to fall into a trap of deception. For years the government did not give new land to our family. My family had nothing except our land, and that too was taken away from us. We had to come here (Delhi) to feed our kids and family.” 2 Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations sector, they are unable to hold onto them and engage as daily wage workers in low-paid, less productive jobs. As a result, they are often subjected to food insecurity, increased mortality, morbidity, etc. (Fernandes 2008). Though the entire Adivasi community suffers the impact of landlessness and joblessness, women feel their ill-effects way more than men. From growing their own food and selling it directly to having full control over when, where, and how they work, they suddenly lose all of that, and become dependent on their menfolk, or have to work as laborers in horrible conditions themselves; while their fathers, husbands, and sons drink more, as despair takes over. “ Humari zameen khone ke baad, mere pati ne sharab ki bheed mai jaana shuru kardiya. Yeh unka humari haalton se jhujne ka raasta tha.”3 Roma’s husband, Ram, turned to alcohol as a means to cope with the stress and anxiety caused due to the loss of land and livelihood. It wasn't until one day Ram came home late at night stumbling and unable to speak properly that Roma discovered he was struggling with alcohol which left her both shocked and deeply concerned for his well-being. Roma noted over time how Ram's drinking became more and more frequent. He would often come home drunk, shouting and causing a scene, and the children were terrified of him. There were even days when he would lash out at her and push her in anger. Ram’s alcoholism had far-reaching consequences for his family as he was unable to work and the family struggled to make ends meet. Consequently, Roma was forced to work long hours as a domestic helper. “Ram toh pure din bahar ghumte aur sharab peete, lekin mujhe toh apne ghar-parivar ka dhyaan rakhna hota hai. Agar mai bhi bahar chale jai toh mere baccho ko kon sambhalega?”4 This anecdote provided by Roma highlights how after getting displaced from their native lands, 3 Translation: “My husband started drinking heavily after we were displaced from our land. It was his way of coping with the trauma.” 4 Translation: “Ram stays out and drinks alcohol the entire day. If I also start going out, then who will take care of my children?” Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations Adivasi women increasingly bear the brunt of beatings from their men as cases of domestic violence go up, largely due to alcoholism. The deplorable conditions are magnified for Adivasi women by their “gender roles and the simultaneous demands of work and childcare.” (Shah 1997) Due to the disproportionate burden of work and increased difficulties in fulfilling her responsibilities as the caretaker of her family, Roma had reduced access to the outside world in the post-displacement economy. “ Hume jab plant ne apne hi zameen aur logo se alag kardiya toh humare paas paani aur khaane ka koi saadhan nahi tha. Mujhe har din das (10) kilometer dur jakar paani bharke laana hota tha.”5 Ms. Roma highlights how the despair of Adivasi women is not just restricted to domestic violence. Like most women in Western societies, they face a “double burden of work”, a concept discussed by Betty Friedan in her book “The Feminine Mystique (1963)” since they have to juggle between their “paid and unpaid work”. However, this burden is intensified for Adivasi women due to the development-induced displacement. Even after losing their land and forests, women’s role of ensuring the supply of fuel, water, and other family needs remains unchanged, however, they have to cope with it with reduced access to resources. (Ganguly 1995) Due to the construction of the NTPC power plant, the environmental resource base collapsed which made it difficult for Roma Devi to fetch fuel and water for her family. As a result, she had to travel long distances and work for longer durations. Furthermore, there exists a gender bias in the government’s resettlement policy. Though the state claims that it takes the necessary measures to resettle the displaced Adivasis, its Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy (R&R) doesn’t recognize the gendered implications of displacement for women. For instance, the R&R package announced comprised a minimum of two hectares of irrigated land for each landholder, however, in most cases, allotment of land and cash compensation was made in the name of the male Translation: “When the power plant separated us from our land and community, we had no means of water and food. I had to go ten kilometers every day to fetch water.” 5 Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations member of the family. In combination, all this reduces the identity of Adivasi women to mere housewives as they become increasingly dependent on their husband’s single salaries. (Fernandes 2008) In her 1994 book, ‘Population and Environment: Rethinking the Debate’, Bina Agarwal elaborates on the important connections between the domination and oppression of women and the domination and exploitation of nature. Due to their “specific form of interaction with nature”, she states that Adivasi women have a “special dependency” on nature and can be seen much closer to the environment than men. The relationship of women with nature needs to be understood as “rooted in their material reality, in their specific form of interaction with nature.” A gender-based division of labor structures people’s interactions with nature and influences how they are affected by environmental degradation and their responses to it. In tribal communities, women are the main cultivators and are also responsible for fetching fuel, fodder, and water. It is because of their everyday interaction with nature that they have a special dependence on nature and a special knowledge of it. (Agarwal 1994) Adivasi women have a particularly high stake in the ecological resources of their locality and thus stand to lose more from its degradation as a result of the developmental projects. This also explains why Adivasi women can be seen playing a leading role in environmental movements such as the Narmada Bachao Andolan, Chipkoo Movement, etc. It is evident that the Adivasi community suffers tremendously due to the loss of land and access to environmental resources. The loss of livelihood without alternatives resulting from displacement leads to their impoverishment and marginalization to such an extent that is not prior to any state of poverty. However, the focus of this paper is to highlight the further hardships faced by Adivasi women through the lens of Roma Devi’s story when the community support structures disintegrate and they lose their traditional way of living. The narratives presented by Roma Devi clearly bring out the various economic and social aspects of the marginalization of Adivasi women. Losing the common pool resources, which are a locus of their work, their identity gets reduced from having a relatively higher status to being mere housewives. They not Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations only experience increased domestic violence but also lose their economic security due to their disadvantageous position assigned by patriarchal gender relations. Indeed, it is the Adivasi community that bears the brunt of the “dust of development”, however, the conditions are worsened for Adivasi women who get degraded both economically and socially. Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations References Kerketta, Jacinta. (2016). Angor: Poems by Jacinta Kerketta. Adivaani Debasree, D. (2015). Development-induced displacement: impact on adivasi women of Odisha. Community Development Journal, 50(3), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsu053 Mankodi, Kashyap. (1989). ‘Displacement and Relocation: Prospects and Problems’ in Fernandes, W., & Thukral, E. G. Development, Displacement, and Rehabilitation: Issues for a National Debate. Indian Social Institute. Fernandes, Walter. “Chapter 6: Sixty-Years of Development-Induced Displacement in India in Mathur, H. M. (2008). India - Social Development Report 2008: Development and Displacement. Oxford University Press, USA. Agarwal, Bina. (1994) Chapter 4. “Population and Environment: Rethinking the Debate” by Arizpe, Lourdes, et al. Westview Press. Shah, Vidya. (1997) “Khedpada - a case study in migration.” Report for WIRFP Seasonal labor migration study. Ganguly Thukral, Enakshi, and Mridula Singh. (1995) ‘Dams and the Displaced in India’ in Hari Mohan Mathur (ed) “Development, Displacement, and Resettlement: Focus on Asia”. Vikas Publishing Company. Dhruv Goyal FC-0201-1 Indian Civilisations